|

The Film

American Horror Project Vol 1

The Premonition (Robert Allen Schnitzer, 1976) The Premonition (Robert Allen Schnitzer, 1976)

In his wonderful book Nightmare USA: The Untold Story of the Exploitation Independents, Stephen Thrower (the co-curator of Arrow’s new American Horror Project Volume 1 set) locates Robert Allen Schnitzer’s off-kilter ESP-oriented picture The Premonition (1976) alongside another film included in Arrow’s boxed set, The Witch Who Came from the Sea (Matt Cimber, 1976), as one of a number of American horror films made during the 1970s that ‘bred horror with something not unlike the stranger reaches of European art cinema’ (Thrower, 2008: 13). Thrower also lists Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck & Gloria Katz, 1973) and Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (Richard Blackburn, 1973) as examples of this trend. Thrower also highlights The Premonition, along with Psychic Killer (Ray Danton, 1975), as one of a group of films which explored the phenomenon of psychic ‘gifts’ or abilities prior to the trend in what Thrower labels ‘psi-fi’ (psychic-fiction) that followed in the wake of Brian De Palma’s 1976 film adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Carrie (ibid.: 41).

Shot cheaply in Mississippi, The Premonition begins with the arrival of Andrea Fletcher (Ellen Barber) at the site of a rundown travelling carnival, where she meets with Jude (Richard Lynch), one of the carnival’s employees. Jude is a mime who also doubles as the carnival’s photographer, using an old Speed Graphic camera to photograph visitors, especially children. Andrea has recently been released from a psychiatric hospital and Jude, her lover, has got in touch with Andrea to tell her that whilst photographing some child visitors to the carnival, he saw a young girl who he is sure is Janie (Danielle Brisebois), Andrea’s estranged daughter. Janie was taken from her mother, owing to her mother’s unspecified psychiatric illness, and placed with a childless couple: Sheri Bennett (Sharon Farrell) and her husband Professor Miles Bennett (Edward Bell), a scientist.

Andrea seeks Jude’s help in snatching Janie from the Bennetts. When this takes place, it pushes Sheri Bennett – who has already suffered from visions which may be evidence of psychic powers – into hysteria. Detective Lieutenant Mark Denver (Jeff Corey) investigates, hoping to reunite Janie with the Bennetts. Meanwhile, Jude, who is already on edge, is goaded to fury by Andrea, resulting in Jude’s murdering of his partner. Jude returns to the carnival, taking Janie with him. As Andrea’s visions become dominated by images of the now deceased Andrea, Miles begins to pay attention to the work of his colleague at the university, Dr Jeena Kingsly (Chitra Neogy), who is an expert in parapsychology. Kingsly suggests that she may be able to help the Bennetts locate Janie, but the discovery of Andrea’s corpse by the police gives an increasingly desperate edge to the search for the child. Andrea seeks Jude’s help in snatching Janie from the Bennetts. When this takes place, it pushes Sheri Bennett – who has already suffered from visions which may be evidence of psychic powers – into hysteria. Detective Lieutenant Mark Denver (Jeff Corey) investigates, hoping to reunite Janie with the Bennetts. Meanwhile, Jude, who is already on edge, is goaded to fury by Andrea, resulting in Jude’s murdering of his partner. Jude returns to the carnival, taking Janie with him. As Andrea’s visions become dominated by images of the now deceased Andrea, Miles begins to pay attention to the work of his colleague at the university, Dr Jeena Kingsly (Chitra Neogy), who is an expert in parapsychology. Kingsly suggests that she may be able to help the Bennetts locate Janie, but the discovery of Andrea’s corpse by the police gives an increasingly desperate edge to the search for the child.

In Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career, Edmund G Bansak suggests that The Premonition stood out in the post-Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) era of ‘zoological nightmare[s]’ (Bansak, 1995: 520). Bansak goes so far as to refer to The Premonition as a ‘Lewtonesque oasis’ during that specific era of American horror cinema (ibid.). Aside from a handful of short films, The Premonition’s director, Robert Allen Schnitzer, had only one feature to his credit prior to making the picture: No Place to Hide, focusing on radical students during the late 1960s, and starring in a very early screen role Sylvester Stallone. Like a number of Stallone’s early pictures, No Place to Hide has been re-edited and rereleased a number of times – first in 1973, again as Rebel in 1980 and later in a comedy version as A Man Called… Rainbo in 1990.

We are introduced to Jude as he exits his trailer and stretches outside, practicing his mime routing in the morning sun and to the accompaniment of non-diegetic piano music. (The choice of piano music foreshadows Andrea’s arrival at Jude’s trailer: as revealed much later in the film, Andrea has a concealed talent for playing the piano.) In one of the film’s many interesting compositions that make intentional use of lens flare, the camera shoots Jude from behind as his arms reach up to the sky, blocking out the sun, before he lowers them and allows the sun to be framed between his hands, its light flaring in the lens of the camera. He meets with Andrea, who walks towards him as, in a point-of-view shot from Jude’s perspective as he exercises and buries his head between his knees, we see her upside down; her inversion within the composition perhaps mirrors her ‘inversion’ in a moral or psychological sense. We are introduced to Jude as he exits his trailer and stretches outside, practicing his mime routing in the morning sun and to the accompaniment of non-diegetic piano music. (The choice of piano music foreshadows Andrea’s arrival at Jude’s trailer: as revealed much later in the film, Andrea has a concealed talent for playing the piano.) In one of the film’s many interesting compositions that make intentional use of lens flare, the camera shoots Jude from behind as his arms reach up to the sky, blocking out the sun, before he lowers them and allows the sun to be framed between his hands, its light flaring in the lens of the camera. He meets with Andrea, who walks towards him as, in a point-of-view shot from Jude’s perspective as he exercises and buries his head between his knees, we see her upside down; her inversion within the composition perhaps mirrors her ‘inversion’ in a moral or psychological sense.

Jude and Andrea talk in a roundabout manner, Jude navigating around the issue of his ‘discovery’ of Janie’s location. He tells Andrea, ‘This time it’s positive. I know it’s her’. Andrea suggests that she is surprised Jude has remembered her, and as the narrative progresses it’s never quite clear why Jude is so invested in helping Andrea – especially after her nagging causes him to murder her. ‘I thought you’d forgotten about me, Jude’, Andrea says during their first conversation in Jude’s trailer. ‘I told you I’d call you as soon as I found something’, Jude reminds her in response. Andrea reminds him that he has presented her with false hope before: ‘What if it’s not her?’, Andrea asks, ‘What it it’s like all the other times? What then?’ ‘We’ll wait’, Jude informs her, ‘And we keep on waiting until we find her’.

The film contrasts two sets of parents vying for Janie: Jude and Andrea, transient and unconventional, are juxtaposed with Miles and Sheri, settled and bourgeois. Both Andrea and Sheri seem to have their bouts of hysteria, though Sheri seems more successful at masking them. Meanwhile, Sheri, Andrea and Jude are all linked by their psychic visions. (Even Jeena, the other significant female role in the picture, is linked to the psychic realm by her experiments in parapsychology.) At one point, Jude suggests to Andrea that once they have Janie, they should buy a house and settle down, like the Bennetts: ‘It’d be good for the kid. It’d be good for Janie’, Jude reasons. ‘Settle down?’, Andrea asks angrily in a sudden change of mood, What are you talking about settling down for? [….] Sometimes I don’t understand you, Jude. Settling down for what? This comes first’. Where there are strong similarities between the two ‘mothers’ vying for Janie, Jude and Miles are radically different from one another. Where Jude is employed as a mime in the carnival, Miles works as a scientist and reacts to his colleague Jeena’s experiments in parapsychology with skepticism – at least initially.

The film establishes an almost dualistic relationship between Miles and Jeena, their conversations sometimes feeling rather didactic in terms of the deliberate contrasts between Jeena’s investment in parapsychology and Miles’ (initial) disbelief in the subject. Jeena is introduced in a lab, where the subjects of her experiments are laid down and hooked up to electronic equipment. ‘Evidence of telepathy appears most readily when the unconscious mind is most receptive’, she explains to a visitor, ‘and it’s most receptive in the dream state’. She is introduced to Miles Bennett, engaging him in a philosophical discussion about the nature of reality: she tells him, ‘Try to understand: the phenomena of the real world reveals sometimes more the nature of the mind than the nature of things’. Later, Bennett engages Jeena in another conversation about her work, and reflecting on some of her previous comments he suggests that what she is really saying is that ‘consciousness is more primordial than matter’. ‘Are you ready to accept that?’, Jeena asks him in response. Bennett suggests that this particular premise is difficult to come to terms with. ‘Then how do you account for telepathy or precognition or retrocognition?’, Jeena asks. ‘I’m not sure that I do’, Bennett answers: implicit within his response is the suggestion that the none of the phenomena listed by Jeena should be taken at face value. However, Jeena has a dogmatic response to this, telling Bennett that ‘That’s because the fundamental principles on which your science is based are incomplete’. Jeena’s expressions of the tenets her discipline become more gnomic, at times echoing the aphoristic reasoning expounded by ‘television prophet’ Brian O’Blivion in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982): ‘The fundamental foundation of modern science is that we are separate entities and everything is external to us’, Jeena asserts during a seminar at the university, adding that ‘The clairvoyant reality is totally rejected by science, and finds expression only in art, music, religion’. Finally, when Andrea’s spirit seems to haunt Sheri, taunting her about Janie’s disappearance, Jeena advises Miles that ‘There’s not much time. We must now deal completely within the metaphysical system’. The film establishes an almost dualistic relationship between Miles and Jeena, their conversations sometimes feeling rather didactic in terms of the deliberate contrasts between Jeena’s investment in parapsychology and Miles’ (initial) disbelief in the subject. Jeena is introduced in a lab, where the subjects of her experiments are laid down and hooked up to electronic equipment. ‘Evidence of telepathy appears most readily when the unconscious mind is most receptive’, she explains to a visitor, ‘and it’s most receptive in the dream state’. She is introduced to Miles Bennett, engaging him in a philosophical discussion about the nature of reality: she tells him, ‘Try to understand: the phenomena of the real world reveals sometimes more the nature of the mind than the nature of things’. Later, Bennett engages Jeena in another conversation about her work, and reflecting on some of her previous comments he suggests that what she is really saying is that ‘consciousness is more primordial than matter’. ‘Are you ready to accept that?’, Jeena asks him in response. Bennett suggests that this particular premise is difficult to come to terms with. ‘Then how do you account for telepathy or precognition or retrocognition?’, Jeena asks. ‘I’m not sure that I do’, Bennett answers: implicit within his response is the suggestion that the none of the phenomena listed by Jeena should be taken at face value. However, Jeena has a dogmatic response to this, telling Bennett that ‘That’s because the fundamental principles on which your science is based are incomplete’. Jeena’s expressions of the tenets her discipline become more gnomic, at times echoing the aphoristic reasoning expounded by ‘television prophet’ Brian O’Blivion in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982): ‘The fundamental foundation of modern science is that we are separate entities and everything is external to us’, Jeena asserts during a seminar at the university, adding that ‘The clairvoyant reality is totally rejected by science, and finds expression only in art, music, religion’. Finally, when Andrea’s spirit seems to haunt Sheri, taunting her about Janie’s disappearance, Jeena advises Miles that ‘There’s not much time. We must now deal completely within the metaphysical system’.

Some of the film’s most unsettling scenes take place prior to Jude and Andrea’s abduction of Janie. Early in the film, Andrea visits Janie’s school, watching the child through the fence. Where Sheri’s psychic visions are unsettling because they come after the film has established her as living a settled, bourgeois lifestyle characterised by responsibility and security – in contrast to the transient, disordered lives led by Jude and Andrea – the preconceptions the audience might hold about Andrea are suddenly undercut when, part-way through the picture, she is revealed to be an accomplished pianist. Meanwhile, Sheri experiences nightmarish visions of Andrea and Jude. These two women come together when Andrea breaks into the Bennett house at night with the intention of abducting Janie. Shot in a low-angle shot that is framed at an obtuse angle, Andrea advances out of the darkness towards the sleeping Janie, her face framed in shadow and hinting towards her ‘dark’ motives; her red dress and red lipstick indexical of danger. Andrea’s movement towards Janie’s bed is interrupted by a high angle shot of the sleeping child, completely unaware of what is taking place. Sheri bursts into the room, and the two women fight cruelly, Andrea escaping back into the night, fleeing with a doll that acts as a metonym for her status as an alienated mother, and a declaration that ‘She is mine! And she’ll always be mine!’

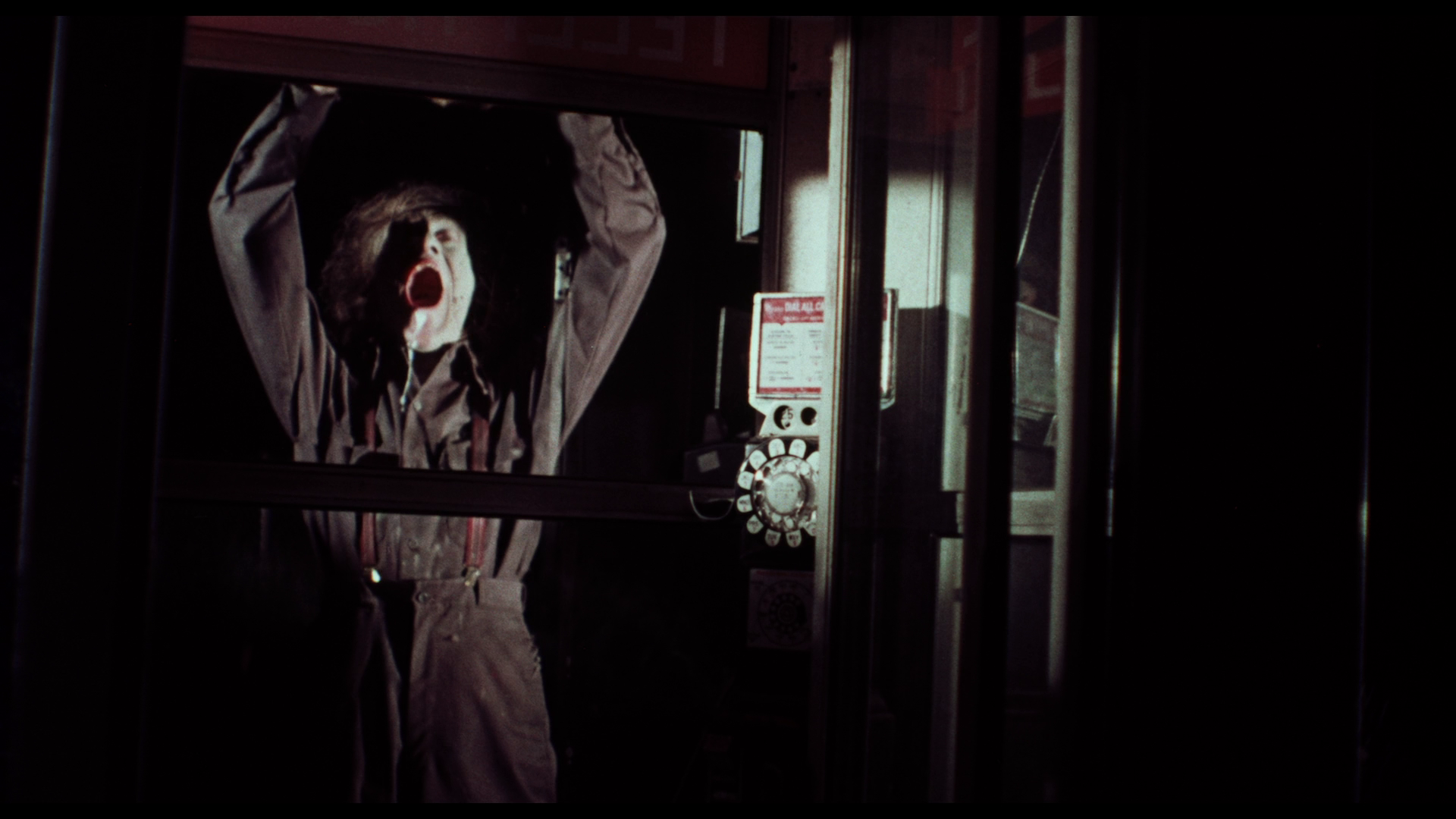

When Jude realises that Andrea was unsuccessful and has returned with a doll rather than the child to which it belongs, he asks her, ‘What are we gonna do with a goddamn doll?’ In response, the clearly disturbed Andrea screams animalistically. At their rural hideout, Andrea seems to have lost all touch with reality: she talks to the doll as if it were a child. Jude, frustrated, snatches the doll from Andrea and tears off its head, causing Andrea to scream, ‘My baby!’ ‘Your baby is back in its goddamn house with its mother’, Jude tells Andrea unsympathetically and with brutal honesty. ‘What is it to you?’, Andrea screams back at him, ‘You aren’t her father! You’re nobody’s father. You’ll never be anybody’s father! You aren’t even a goddamn man’. Whether Andrea is alluding to Jude’s impotence or perhaps his ambiguous sexuality is unclear, but regardless this sleight against his masculinity sends Jude into a murderous rage, and he advances on Andrea with a flick-knife before the film cuts to Sheri, who receives a telephone call from now-dead Andrea telling Sheri that ‘There’s nothing you can do. I’m coming for my baby’. In the ellipsis between the two scenes, the viewer may conclude that Jude murders Andrea, and the discovery of her corpse later in the picture – shot in a matter-of-fact way as Andrea is dragged out of a lake, her red dress underscoring the centrality of her corpse to the composition and narrative – confirms this. When Jude realises that Andrea was unsuccessful and has returned with a doll rather than the child to which it belongs, he asks her, ‘What are we gonna do with a goddamn doll?’ In response, the clearly disturbed Andrea screams animalistically. At their rural hideout, Andrea seems to have lost all touch with reality: she talks to the doll as if it were a child. Jude, frustrated, snatches the doll from Andrea and tears off its head, causing Andrea to scream, ‘My baby!’ ‘Your baby is back in its goddamn house with its mother’, Jude tells Andrea unsympathetically and with brutal honesty. ‘What is it to you?’, Andrea screams back at him, ‘You aren’t her father! You’re nobody’s father. You’ll never be anybody’s father! You aren’t even a goddamn man’. Whether Andrea is alluding to Jude’s impotence or perhaps his ambiguous sexuality is unclear, but regardless this sleight against his masculinity sends Jude into a murderous rage, and he advances on Andrea with a flick-knife before the film cuts to Sheri, who receives a telephone call from now-dead Andrea telling Sheri that ‘There’s nothing you can do. I’m coming for my baby’. In the ellipsis between the two scenes, the viewer may conclude that Jude murders Andrea, and the discovery of her corpse later in the picture – shot in a matter-of-fact way as Andrea is dragged out of a lake, her red dress underscoring the centrality of her corpse to the composition and narrative – confirms this.

Andrea’s death increases the psychic power she wields over Sheri. Sheri’s visions become more vivid and dominated by the image of Andrea. The hallucinations are both visual and auditory. Following Andrea’s death, Sheri receives the telephone call from Janie’s dead mother; aware that something is wrong, Miles attempts to listen to the call, but the line goes dead before he is able to, thus denying any confirmation that Andrea is reaching out to her rival from beyond the grave. Miles convinces Sheri that she should meet with Jeena and discuss her visions with the parapsychologist, but driving in her car Sheri experiences a vision of the car’s windscreen fogging over. This causes her to lose control of the car. However, the sequence suggests that Janie experiences the vision too: either Janie shares Sheri’s psychic link with the dead Andrea, or Andrea is able to manipulate the physical world from beyond the grave, in the manner that Jeena has earlier suggested to both Miles and her students. Sheri crashes the car, providing Jude with an opportunity to snatch Janie; why Andrea may have decided to help Jude is unclear, as is the reason why Jude is in the right place at the right time and therefore able to kidnap the child whilst Sheri has been knocked out from the collision. Nevertheless, Andrea’s ghostly laughter on the film’s audio track seems to suggest that Andrea is omnipresent, or at the very least omniscient: even after her death, the narrative is haunted by her presence. Finally, the viewer might be left reflecting on Lieutenant Denver’s pointed assertion to Miles, that ‘Something’s not adding up. There’s too many weird things going on’.

Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (Christopher Speeth, 1973) Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (Christopher Speeth, 1973)

At a static carnival, Vena Norris (Janina Carazo) and her parents (Paul Hostetler and Betsy Henn) take jobs with the intention of investigating the disappearance of their son Lucky (Sebastian Stuart). Vena makes friends with Kit (Chris Thomas), who mans some of the carnival games. Unaware of the real reason why Vena and her parents have sought employment at the carnival, Kit warns Vena that ‘Some kids were killed here, or at least that’s the story we’re all weaned on’.

A flashback reveals that Lucky entered the carnival one night with some of his friends. Lucky took a solo ride on one of the carnival’s rollercoasters but when the car arrived at the end of the ride he had been decapitated; then he and his friends disappeared, the corpses carried into a device where they are exsanguinated and devoured by singing ghouls(!) The film returns to the present, where Vena meets Bobo (Herve Villechaize) and begins to experience strange, portentous nightmares. When Vena discovers Kit’s corpse on one of the rides, she realises that the danger within the carnival is very real; and this is confirmed for her when her parents are killed in their trailer, Blood claiming that it was an accident. When Vena disappears, her lover Johnny (Paul Townsend) arrives at the carnival looking for her.

The film opens with Vena having her fortune read from a Tarot deck by the carnival’s cartomancer. (The use of the Tarot deck in this sequence recalls that other release of 1973 which prominently features a Tarot deck in its opening sequence, Mario Bava’s Lisa e il diavolo/Lisa and the Devil.) The cartomancer turns over the death card and abruptly ends the Tarot reading, ushering Vena out of the door and insisting to her that such a reading is free to all new employees of the carnival. The film uses the card as a symbol of physical death, foreshadowing the peril in which the Norris family have placed themselves unknowningly; but as even the most inexperienced student of Tarot knows, the death card does not necessarily represent a physical death (ie, the end of a life) but can instead symbolise the end of a stage in someone’s life or the collapse of a relationship. Premonitions of danger and doom fill the film’s early sequences: in Mr Blood’s refusal of the Norris’ dinner invitation are echoes of the words of Count Dracula in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897); Vena’s mother suggests at one point that ‘We should get out of here tonight. This place is… evil. I can feel it’. However, her husband fails to heed her warning, telling her that ‘If something’s happened to him [their son Lucky], then I’ll have my revenge’. However, Vena’s mother adds that ‘We can’t be separated. That’s what they want’.

The carnival’s business manager is Mr Blood (Jerome Dempsey), a man whose focus on business and finance hints at his true identity as a blood-sucking vampire. When Vena’s parents invite Mr Blood for dinner, he refuses, telling them that ‘My metabolism is most unusual [….] I feel every moment is a triumph over death’. Showing a couple round the carnival, Mr Blood introduces them to Mr Bean (Tom Markus), the ‘oldest member of the carnival’, who lost a hand owing to an unspecified accident. ‘Yes, sir. Mr Bean is quiet enough’, Blood tells the couple, ‘There’s only one thing Mr Bean likes more than quiet, and that’s money. That’s why he’s in the business’. Later in the film, when Johnny arrives at the carnival he is introduced to Mr Bean, who tells him ‘You’ll need good luck [….] Accidents. We’ve had lots of accidents here’. In a deliciously darkly comic scene, Bean shows Johnny his collection of sketches of medieval torture devices, telling the youth, ‘Listen, lad. They say that meat builds flesh and gives you new life. Do you believe that? [….] So wouldn’t it follow that a man could live longer and longer if he ate more of the same?’ The carnival’s business manager is Mr Blood (Jerome Dempsey), a man whose focus on business and finance hints at his true identity as a blood-sucking vampire. When Vena’s parents invite Mr Blood for dinner, he refuses, telling them that ‘My metabolism is most unusual [….] I feel every moment is a triumph over death’. Showing a couple round the carnival, Mr Blood introduces them to Mr Bean (Tom Markus), the ‘oldest member of the carnival’, who lost a hand owing to an unspecified accident. ‘Yes, sir. Mr Bean is quiet enough’, Blood tells the couple, ‘There’s only one thing Mr Bean likes more than quiet, and that’s money. That’s why he’s in the business’. Later in the film, when Johnny arrives at the carnival he is introduced to Mr Bean, who tells him ‘You’ll need good luck [….] Accidents. We’ve had lots of accidents here’. In a deliciously darkly comic scene, Bean shows Johnny his collection of sketches of medieval torture devices, telling the youth, ‘Listen, lad. They say that meat builds flesh and gives you new life. Do you believe that? [….] So wouldn’t it follow that a man could live longer and longer if he ate more of the same?’

Where The Premonition was shot in Mississippi, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood was filmed in Pennsylvania, at the Six Gun Territory amusement park (previously known as Willow Grove Park). The qualities of a decaying, past-its-prime amusement park are in abundance here: overgrown with weeds, the rides and buildings are covered in peeling paint. Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood takes place in a tradition of American horror/dark fantasy stories revolving around carnivals – both static and traveling. These include pictures like Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide (1960), Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962) and Robert Kaylor’s Carny (1980); novels such as William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley (1946) and Stephen King’s Joyland (2013); and television shows such as HBO’s Carnivale (2003-5). In its depiction of a carnival headed by the perverse Mr Blood, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood seems to take some elements from Ray Bradbury’s 1962 novel Something Wicked This Way Comes (published in the same year as the release of Carnival of Souls, suggesting something in the zeitgeist regarding the carnival – and the notion of the carnivalesque – within American culture), in which two teenage boys are exposed to a nightmarish ordeal following their encounter with a traveling carnival owned by a man named Mr Dark. (Bradbury’s novel has been a heavy influence on the work of Stephen King: Joyland makes reference to Something Wicked This Way Comes, and elements from the book found their way into King’s Doctor Sleep, 2014, and Revival, 2015.) Even photographic documentations of carnivals and circuses in American culture contain something of the liminal and nightmarish: for example, Luke Swank’s photographic portraits of clowns, and Bruce Davidson’s 1958 photo essay Circus (published as a book in 2007).

Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood offers some sly observations about both carnival life, the politics surrounding it, and wider society. In one sequence, a spoilt, demanding child (reminiscent of Veruca Salt from Roald Dahl’s 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory) turns up at the carnival with her parents, who, in reference to the girl’s rude, obnoxious behaviour, state that ‘It’s such a strain having an intelligent child’. The girl and her parents take a ride on the Tunnel of Love but when the car in which they are seated exits the ride, the family have vanished. Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood offers some sly observations about both carnival life, the politics surrounding it, and wider society. In one sequence, a spoilt, demanding child (reminiscent of Veruca Salt from Roald Dahl’s 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory) turns up at the carnival with her parents, who, in reference to the girl’s rude, obnoxious behaviour, state that ‘It’s such a strain having an intelligent child’. The girl and her parents take a ride on the Tunnel of Love but when the car in which they are seated exits the ride, the family have vanished.

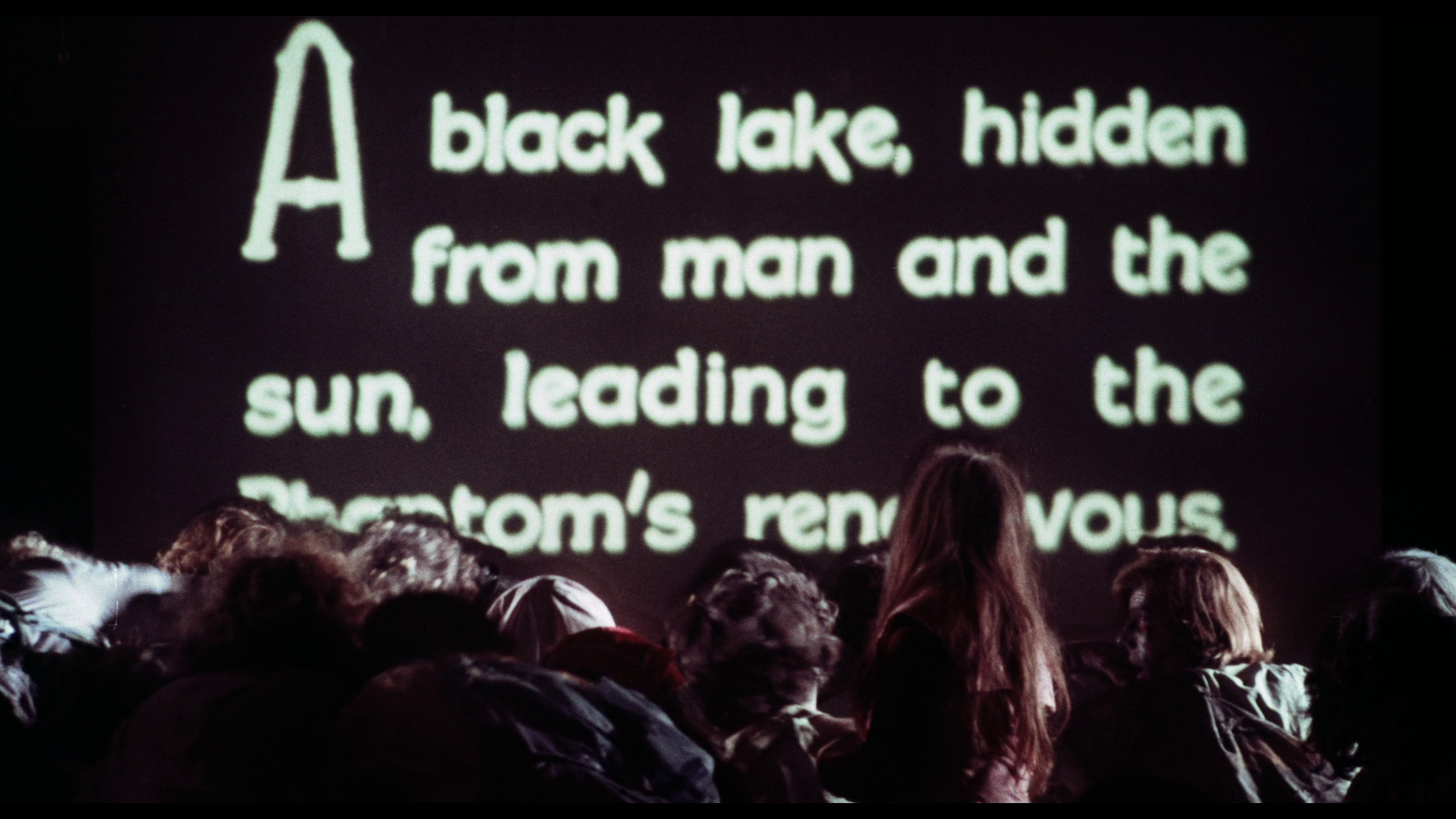

In The Premonition, Jude is associated with a traveling carnival. Working as a mime and photographer, Jude’s status as a ‘nomad’ enables him to locate Janie, Andrea’s biological daughter. By contrast, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood is located in a static carnival, and the vampiric/cannibalistic creatures that populate this carnival wait for their prey to come to them. Blood seems to be the leader of the vampiric ghouls; though the exact nature of the hierarchy within the carnival seems ambiguous, at the peak is the enigmatic Malatesta, the owner of the carnival. The nature of the carnival having already been revealed to Vena, she is held captive and Blood suggests that he wishes to help her escape. Vena says to Blood, ‘You’re evil’. In response, Blood tells her, ‘No, I’m not, Vena. You must believe me’. He claims that Malatesta is ‘mad and evil. Too evil. I wanted to destroy him. I didn’t realise…’ He suggests that he is a prisoner of the carnival too, having fallen under the spell of Malatesta and being stripped of his own free will. The inhabitants of the carnival also seem to be able to intrude upon the unconscious minds of those who enter into their world. Following the analepsis that depicts Lucky’s death on the rollercoaster, Vena meets Bobo for the first time, and Bobo warns her ominously to ‘Beware of the evil who strikes in the shadow of a dream’. Soon after, Vena experiences a vivid nightmare, her dreams haunted by Malatesta.

The names of the carnival’s inhabitants are obviously symbolic of their tendencies: Blood is of course a vampire; and Bean is a cannibal. Bean’s name seems to allude to the cannibalistic Sawney Bean family, who legend suggests lived in a coastal cave in Bennane Head during the 16th Century. The connection to the Bean clan is underscored when Blood tells Vena that the ‘carnival was constructed over a series of natural limestone caverns. That is how Bean has kept his family undetected for so many years [….] And they’re cannibals, every one. Most of them have never seen the light of day. That’s why they look so ghastly. Live like animals. Nobody as told them that eating people is wrong, so how are they to know?’ Blood, the carnival’s business manager, represents the outward face of the carnival: he is dressed in a sharp suit and has the easy, confident manners of the bourgeoisie. The ghouls beneath him are distinctly proletarian, clothed in rags and their faces caked in dirt. They attack in groups: their assault on the trailer of Vena’s parents is filmed with the shadows of the ghouls falling over the trailer before the creatures shamble into the frame, in a manner that recalls George A Romero’s depiction of the zombies in Night of the Living Dead (1968). In fact, the ghouls in Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood are uncannily similar to those in Andy Milligan’s London-set vampire picture The Body Beneath (1970), their faces and bodies covered in stage paint. Like Milligan’s vampires, they operate in groups and descend on their prey in unison, and they even engage in a good old-fashioned sing-song over a corpse or two. Like Andy Milligan’s films, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood is illogical (which, as Stephen Thrower suggests in the introduction on this disc, is a positive quality, if you’re on the film’s curious wavelength) and, though technically not the most impressive production, seems to be a real labour of love – filled with the joys of theatrics and stagecraft. At one point, Vena tells Kit that ‘I don’t understand anything that’s going on around here’, and the audience may very well share her feelings; to this, she adds that she feels ‘like a fly caught in a spider web’, and through its irrational plotting and dreamlike logic, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood is at its heart a story of predators who ensnare their prey, using the run-down, homely appearance of the carnival to lure them into their web before descending on and devouring them. The names of the carnival’s inhabitants are obviously symbolic of their tendencies: Blood is of course a vampire; and Bean is a cannibal. Bean’s name seems to allude to the cannibalistic Sawney Bean family, who legend suggests lived in a coastal cave in Bennane Head during the 16th Century. The connection to the Bean clan is underscored when Blood tells Vena that the ‘carnival was constructed over a series of natural limestone caverns. That is how Bean has kept his family undetected for so many years [….] And they’re cannibals, every one. Most of them have never seen the light of day. That’s why they look so ghastly. Live like animals. Nobody as told them that eating people is wrong, so how are they to know?’ Blood, the carnival’s business manager, represents the outward face of the carnival: he is dressed in a sharp suit and has the easy, confident manners of the bourgeoisie. The ghouls beneath him are distinctly proletarian, clothed in rags and their faces caked in dirt. They attack in groups: their assault on the trailer of Vena’s parents is filmed with the shadows of the ghouls falling over the trailer before the creatures shamble into the frame, in a manner that recalls George A Romero’s depiction of the zombies in Night of the Living Dead (1968). In fact, the ghouls in Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood are uncannily similar to those in Andy Milligan’s London-set vampire picture The Body Beneath (1970), their faces and bodies covered in stage paint. Like Milligan’s vampires, they operate in groups and descend on their prey in unison, and they even engage in a good old-fashioned sing-song over a corpse or two. Like Andy Milligan’s films, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood is illogical (which, as Stephen Thrower suggests in the introduction on this disc, is a positive quality, if you’re on the film’s curious wavelength) and, though technically not the most impressive production, seems to be a real labour of love – filled with the joys of theatrics and stagecraft. At one point, Vena tells Kit that ‘I don’t understand anything that’s going on around here’, and the audience may very well share her feelings; to this, she adds that she feels ‘like a fly caught in a spider web’, and through its irrational plotting and dreamlike logic, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood is at its heart a story of predators who ensnare their prey, using the run-down, homely appearance of the carnival to lure them into their web before descending on and devouring them.

The Witch Who Came from the Sea (Matt Cimber, 1976) The Witch Who Came from the Sea (Matt Cimber, 1976)

Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came from the Sea (1976) is arguably the most well-known title in this set, owing to its inclusion on the DPP’s list of ‘video nasties’ of the pre-Video Recordings Act era. The picture was struck from the list in 1985 following an unsuccessful attempt to prosecute it for obscenity. The Witch Who Came from the Sea was one of a number of pictures whose appearance on the DPP list was rather perplexing: compared with the graphic delights of a film like Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (Zombie Flesh Eaters, 1979), also on the DPP’s list, The Witch Who Came from the Sea is a relatively bloodless affair. Furthermore, it’s less of a horror film than a psychological study – a melodrama of sorts. Its appearance on the list of ‘video nasties’ may have been owing to the cover art which adorned the pre-VRA release from VTC (VideoTapeCenter): the box art foregrounded the narrative’s themes of incest and castration (both handled in a relatively restrained manner within the film itself) with the tagline which declared that the picture was about ‘A young woman’s nightmare of incest and castration’.

As the film opens, Molly (Millie Perkins) is enjoying an afternoon on the beach with her nephews Tadd (Jean Pierre Camps) and Tripoli (Mark Livingston). Returning the boys to their mother, Molly’s sister Cathy (Vanessa Brown), Molly becomes embroiled in an argument over the character of Molly and Cathy’s father. Molly idealises her father, claiming that he was a sea captain who was ‘too good to live on land’ and was lost at sea; meanwhile, Cathy characterises him as ‘a drunken bum’ who abused both of his daughters. Flashbacks interspersed throughout the film seem to suggest that Molly was the victim of sexual abuse.

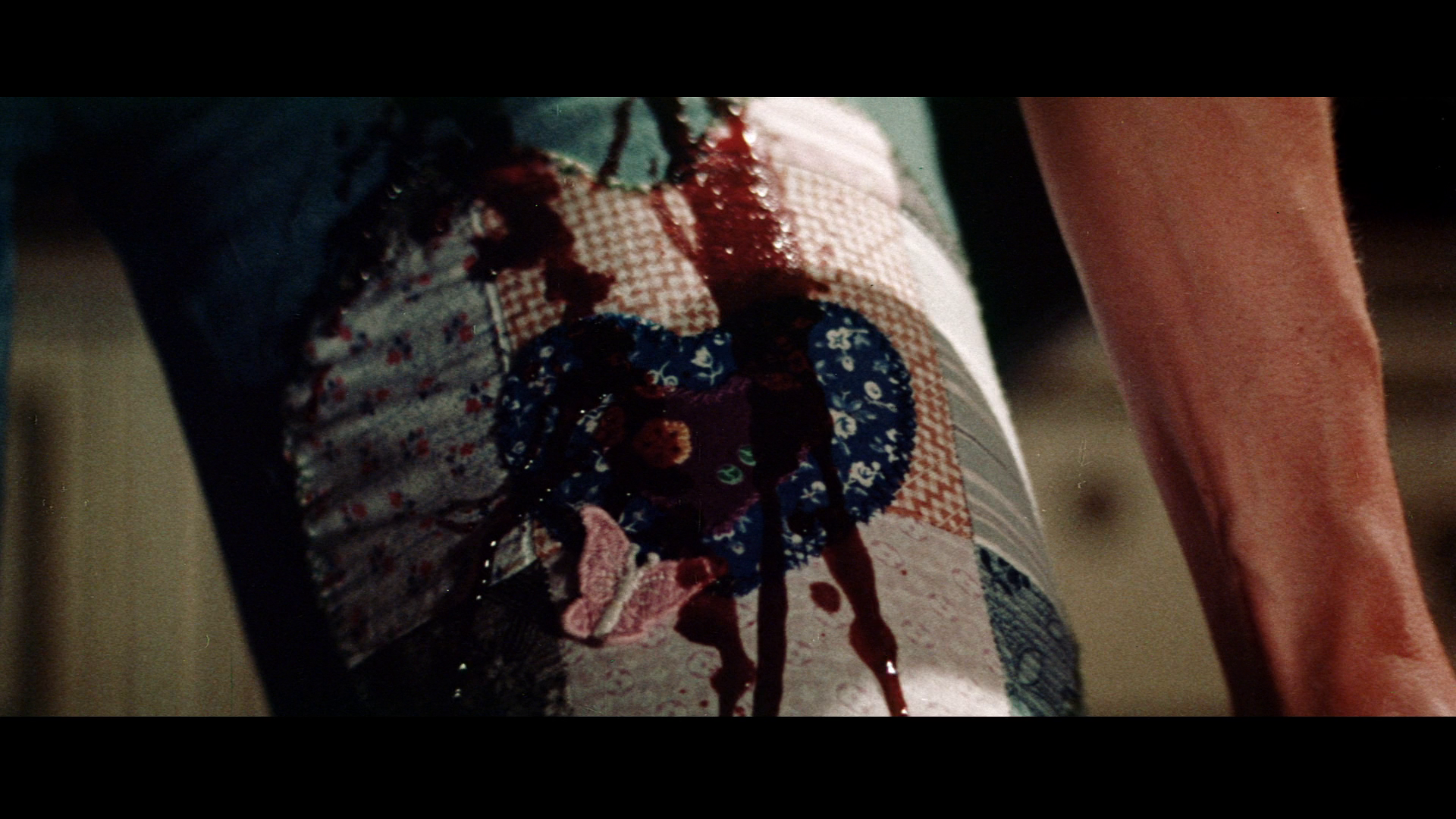

During a sexual encounter with two football players, Molly ties the men together and murders them with a razor blade, mutilating their genitals. As the police search for the murderer, Molly continues with her life, working in a bar with her some-time lover Long John (Lonny Chapman). Long John persuades Molly to visit a party thrown by actor Billy Batt (Rick Jason). There, Batt tries to force himself on Molly, which results in Molly attacking Batt. Batt strikes Molly, knocking her to the floor, where she is aided by Alexander McPeak (Stafford Morgan). Molly recognises McPeak as an actor in television commercials, and Molly ends up in McPeak’s bed, much to the consternation of McPeak’s lover Clarissa (Roberta Collins). During a sexual encounter with two football players, Molly ties the men together and murders them with a razor blade, mutilating their genitals. As the police search for the murderer, Molly continues with her life, working in a bar with her some-time lover Long John (Lonny Chapman). Long John persuades Molly to visit a party thrown by actor Billy Batt (Rick Jason). There, Batt tries to force himself on Molly, which results in Molly attacking Batt. Batt strikes Molly, knocking her to the floor, where she is aided by Alexander McPeak (Stafford Morgan). Molly recognises McPeak as an actor in television commercials, and Molly ends up in McPeak’s bed, much to the consternation of McPeak’s lover Clarissa (Roberta Collins).

Cathy begins to suspect that Molly may have had a part to play in the murders of the two football players, and she shares her suspicions with Long John. Meanwhile, Molly visits a seedy tattoo parlour and has a mermaid tattooed on her stomach and chest. She then returns to McPeak’s bed and murders him with a razor before returning to Long John, covered in blood.

The film foregrounds its coastal setting. It opens with an image of the tide lapping against a beach, Molly and her nephews walking along the tideline, moving slowly towards the camera. This opening image seems to highlight the symbolic importance of the coastline as a place that represents a sense of liminality or ‘in-betweenness’; Molly’s position on the tideline suggests the sense of liminality that characterises her, her visions placing her ‘in-between’ the realms of fantasy, (self-)delusion and reality. The coastal setting is something which features in a number of other, predominantly European, horror pictures of the 1970s. These are films which could loosely be labeled as examples of psychological horror and focus on the mental deterioration of their female protagonists: these include Harry Kumel’s Les lèvres rouges (Daughters of Darkness, 1971), and Jess Franco’s Les possédées du diable (Lorna the Exorcist, 1974) and Christina, princesse de l'érotisme (A Virgin Among the Living Dead, 1973). After being introduced on the tideline, Molly, Tadd and Tripoli sit down in the sand; Molly displays more interest in the men who are exercising on the muscle beach than in her charges. Close-ups of her face are intercut with long lens close-ups of portions of the men’s bodies, including their crotches hidden in tight trunks, their physiques fragmented and objectified in a manner normally associated (in mainstream cinema, at least) with the depiction of women. Molly’s excited stare at the men is punctuated by a nightmarish vision of the men dead, hanged by their exercise equipment or badly injured in falls. This vision introduces Molly’s misandrism, her desire to maim and kill men she desires.

The liminality of the coastal setting also echoes throughout the film’s engagement with Molly’s relationship with her father, who she claims was lost at sea. Cathy disputes Molly’s memories of their parent (‘Grandpa was a drunken bum’, Cathy tells her sons), and as the film progresses a series of flashbacks seem to suggest that Molly was abused sexually by her father. Molly’s story of how her father was a sea captain, these flashbacks suggest, originated in his fascination with the sea: in the first of these analepses, he and a young Molly are putting together a model of a large schooner, before he places Molly on his lap and leers at her cruelly as we are led to believe that, offscreen, he sexually abuses her. (Though, given how unreliable Molly is in the rest of the film, whether or not we can take these analepses at face value is another matter.) Later flashbacks to Molly’s childhood and her abuse at the hands of her father, which punctuate the narrative at fairly regular intervals, suggest that Molly’s father had on his chest the same mermaid tattoo that Molly has applied to her own skin. The liminality of the coastal setting also echoes throughout the film’s engagement with Molly’s relationship with her father, who she claims was lost at sea. Cathy disputes Molly’s memories of their parent (‘Grandpa was a drunken bum’, Cathy tells her sons), and as the film progresses a series of flashbacks seem to suggest that Molly was abused sexually by her father. Molly’s story of how her father was a sea captain, these flashbacks suggest, originated in his fascination with the sea: in the first of these analepses, he and a young Molly are putting together a model of a large schooner, before he places Molly on his lap and leers at her cruelly as we are led to believe that, offscreen, he sexually abuses her. (Though, given how unreliable Molly is in the rest of the film, whether or not we can take these analepses at face value is another matter.) Later flashbacks to Molly’s childhood and her abuse at the hands of her father, which punctuate the narrative at fairly regular intervals, suggest that Molly’s father had on his chest the same mermaid tattoo that Molly has applied to her own skin.

Molly and Cathy’s relationship is characterised by a sense of mutual antagonism which revolves around their memories of their father. Early in the film, they become engaged in a harsh argument over their father. Cathy claims that their father ‘was an evil bastard’, whilst Molly asserts that ‘Papa never put a finger on you, and you know it’. When Cathy infers that Molly was abused by their father, and that he used to kick Cathy, Molly spitefully tells her sister that ‘You have a great imagination, Cathy. You could write something like Little Women, if only you could concentrate’.

Throughout the film, the television seems to play a strong role in Molly’s psychosis. Following her argument with Cathy over their father, Molly watches a television advert but hears her father’s voice over it, the pitch downshifted disorientingly as he says ‘Hey, Molly. Want to come and sail around the world with me, Molly? Just you and me and a big sail, Molly’. Later, when she meets McPeak at Batt’s party, Molly becomes fascinated with him owing to his familiarity from television commercials. ‘Aren’t you a commercial?’, Molly asks him, the curious syntax of the phrase suggesting that she has confused the state of being ‘in’ a commercial with being a commercial itself. After sleeping with McPeak, Molly sees him on television in a commercial for razors, and again she hears him speak with the same downshifted tone that characterises her auditory hallucinations throughout the film: she hears him telling asking her, ‘Why don’t you shave me, Molly? Hot, sweet little bitch’, before cutting his own throat with the blade of the razor. Throughout the film, the television seems to play a strong role in Molly’s psychosis. Following her argument with Cathy over their father, Molly watches a television advert but hears her father’s voice over it, the pitch downshifted disorientingly as he says ‘Hey, Molly. Want to come and sail around the world with me, Molly? Just you and me and a big sail, Molly’. Later, when she meets McPeak at Batt’s party, Molly becomes fascinated with him owing to his familiarity from television commercials. ‘Aren’t you a commercial?’, Molly asks him, the curious syntax of the phrase suggesting that she has confused the state of being ‘in’ a commercial with being a commercial itself. After sleeping with McPeak, Molly sees him on television in a commercial for razors, and again she hears him speak with the same downshifted tone that characterises her auditory hallucinations throughout the film: she hears him telling asking her, ‘Why don’t you shave me, Molly? Hot, sweet little bitch’, before cutting his own throat with the blade of the razor.

Molly’s murder of the two football players is depicted ambiguously, at least initially. Coming after Molly’s auditory hallucination of her father’s voice speaking to her through the television set, the film’s viewer might be tempted to interpret the sequence depicting Molly’s encounter with these two men as a fantasy constructed by a repressed woman. That is, until the murders are confirmed by the police shortly afterwards. Partly, the ambiguity arises from the downshifted pitch of the voices in this sequence, which begins with a shot of Molly framed between the two men. As the trio strip and prepare for a sexual encounter, Molly jokingly tells one of the men to mount the other. In response, one of the football players protests ‘But he’s not my type. You are’, the downshifted pitch of his voice connecting him metonymically to Molly’s father and suggesting that Molly sees these men – and her other male victims within the film – as ciphers for the parent who abused her sexually, this acting as a motive for her desire to mutilate their genitals with a razor blade. Prior to her murder of the football players, Molly ties them together; a close-up of their hands, bound to one another, emphasises the ethnic difference between the two men. Molly gags them before producing the razor blade with which she will torture and kill them. ‘My father shaved with a straight razor’, Molly asserts as she advances on her victims, ‘Bet you’ve never been beaten with a razor strap, have you?’

Molly seems to be drawn to the notion of male perfection, her homicidal rage directed towards men who are handsome, outwardly charming and/or physically ‘fine’ specimens. Her interest in physical beauty causes her to stop before a reproduction of Botticelli’s ‘The Birth of Venus’ during the party at Batt’s home. ‘Who is she?’, Molly asks Batt. ‘She’s a witch, from out of the sea’, Batt tells her. ‘Why did she come out of the sea?’, Molly asks. ‘Venus was born in the sea’, Batt tells her, ‘Her father was a god’, he continues before adding crudely that ‘They cut off his balls. His sperm dropped into the ocean. The sea was knocked up’. ‘Why did Venus…?’, Molly continues, ‘Who did that to her father? I think you’re lying to me’. Molly clearly interprets Batt’s account of Venus’ birth as having relevance to her own relationship with her father, who in a number of scenes she insists was ‘perfect’. However, she concludes her conversation with Batt with a similar assertion to that which she makes when Cathy suggests their father was anything but the idealised figure that Molly presents him to be: ‘I think you’re lying to me’. Molly seems to be drawn to the notion of male perfection, her homicidal rage directed towards men who are handsome, outwardly charming and/or physically ‘fine’ specimens. Her interest in physical beauty causes her to stop before a reproduction of Botticelli’s ‘The Birth of Venus’ during the party at Batt’s home. ‘Who is she?’, Molly asks Batt. ‘She’s a witch, from out of the sea’, Batt tells her. ‘Why did she come out of the sea?’, Molly asks. ‘Venus was born in the sea’, Batt tells her, ‘Her father was a god’, he continues before adding crudely that ‘They cut off his balls. His sperm dropped into the ocean. The sea was knocked up’. ‘Why did Venus…?’, Molly continues, ‘Who did that to her father? I think you’re lying to me’. Molly clearly interprets Batt’s account of Venus’ birth as having relevance to her own relationship with her father, who in a number of scenes she insists was ‘perfect’. However, she concludes her conversation with Batt with a similar assertion to that which she makes when Cathy suggests their father was anything but the idealised figure that Molly presents him to be: ‘I think you’re lying to me’.

The film is notable for its repeated use of the word ‘cunt’ to denote the casual misogyny of the male characters who speak it. The word is first used in Molly’s bedroom encounter with the two football players, one of whom refers to Molly as a ‘cunt’; the harshness of the word, and its aggressive delivery, jars. Later, at Batt’s party, Batt tries to force himself on Molly; when she resists, he slaps her and declares angrily, ‘You really bit me, you cunt’. The appearance of the word, once again, is shocking – especially considering the aggressive context in which it is used. In both instances, the aggressive use of the word ‘cunt’ by a male precedes Molly’s use of violence towards these men. In the case of Batt, Molly ridicules him and snaps his wrist: ‘Could you die for love?’, she asks him, ‘Well, my father did’. However, Batt manages to get the upper hand, striking Molly and knocking her to the floor. Other guests from the party witness this and side with Molly against Batt. However, despite her helplessness in this scenario, the mermaid tattoo Molly has inscribed on her torso reminds us of how dangerous and yet sympathetic Molly is.

Video

Each of the films is housed on its own disc. Each film is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec.

Running 93:04 mins, The Premonition is presented in 1.85:1. A good level of detail is present throughout the film. It’s a beautifully shot picture, with the photography evidencing a keen eye for compositions on the part of the cinematographer; some shots display an arty and self-conscious use of lens flares. There’s a softness to many shots which would seem to be owing to the source material used for this presentation; this source material also evidences some density fluctuations in the emulsions that are noticeable from time to time. Contrast levels are good, though contrast is slightly ‘bold’ in places owing to the fact that this presentation is taken from a source removed from the film’s negative by one or two degrees. Damage is at a minimum, though white flecks and specks are present here and there, and there’s a little gate weave/telecine wobble in a few shots and bold vertical lines, which are notoriously difficult to remove, in a couple of scenes. A strong encode ensures that the film retains the structure of 35mm film. In all, it’s a pleasing presentation of the film, especially if one considers its relative rarity and the face that Arrow didn’t have access to the film’s negative: the damage on display here is all ‘organic’, and the presentation is satisfyingly film-like.

Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood runs for 74:16 mins. In the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, this presentation is sourced from a 35mm print and displays damage from the outset, with bold vertical green lines and flecks and specks appearing fairly regularly throughout the picture. Given that the presentation is taken from a print, the level of detail on display here is very impressive, and the film as a whole has a clearly filmlike appearance that is carried very well by the encode to disc. Again, as with The Premonition, the fact that the presentation is taken from a source that is removed from the negative by two degrees results in an image which has very ‘bold’ contrast, with the loss of shadow detail in a number of sequences. There are a handful of scenes that are saturated in very bold red light, and these have a satisfyingly ‘rich’ appearance in this HD presentation of the film. It’s a fairly carelessly photographed film, with clumsy compositions in many sequences, though there is some very bold, dreamlike imagery that is amplified by the use of short focal lengths that give the film’s depiction of the deserted carnival a nightmarish quality. The presentation on this disc is very satisfying, with the damage that’s present being wholly organic.

Finally, The Witch Who Came from the Sea is presented with a running time of 87:49 mins. Shot by Dean Cundey, this is the most handsomely-photographed film in the set. The 2.35:1 ratio is used to its fullest, and the presentation has a satisfyingly 35mm-like structure. Again, damage is evident from the outset in the form of white flecks and specks, and as with the other two films, this presentation has been sourced from a print, resulting in some stark contrast which to some extent is a product of the original photography (exterior sequences make use of some very bold sunlight) but is also a characteristic of the print-sourced transfer. Colours here are noticeably faded – but not to an extent that would upset one’s enjoyment of the film. The level of detail present in this presentation offers a big improvement over the previous DVD releases of this picture. As with the other two films, this is a pleasing presentation, especially if one factors in the material that was available to Arrow and the lack of access to the film’s negative (which has presumably disappeared into the mists of time).

Audio

All three films are presented with English LPCM 1.0 mono audio tracks, with accompanying optional English subtitles for the hard of hearing. The track for The Premonition is clean and audible throughout, with good range. The same is true for Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood, though the track for this film feels a little ‘tighter’, most likely owing to the shooting conditions. The track for The Witch Who Came from the Sea has more damage to it which is evident from the outset: this track contains noticeable pops and crackles throughout, although this doesn’t affect the clarity of dialogue in any way. (In one sense, the damage to the track sounds reassuringly analogue, with the experience being similar to that of watching a vintage print in a cinema.) Subtitles are clear and easy to read; there’s at least one very minor grammatical error – a confusion of ‘it’s’ with ‘its’ on the subtitles for The Premonition at 72 mins into the picture – but that’s certainly nothing ‘problematic’.

Extras

The set contains a spectacular array of contextual material.

DISC ONE: The Witch Who Came from the Sea DISC ONE: The Witch Who Came from the Sea

- Optional introduction by Stephen Thrower (4:52)

In the introduction to this film, Thrower provides a broad statement of intent for the American Horror Project set overall, and discusses this film’s status as a ‘video nasty’. He compares Millie Perkins’ performance in this picture with Susannah York’s role in Robert Altman’s Images (1972). The Witch Who Came from the Sea, Thrower concludes, is ‘a meditative film, a film of ideas, a film of character’.

- Audio commentary with director Matt Cimber, actress Millie Perkins and DoP Dean Cundey. This is the same commentary which featured on the 2004 DVD release of The Witch Who Came from the Sea by Subversive. The participants discuss the production of the picture in detail, and Cundey’s reflections on the photography are particularly enlightening. All three have vivid recollections of the shoot and provide a wealth of detail about the film. It’s a fascinating, informative commentary track that fans of the film will find most rewarding.in

- ‘Lost at Sea’ (3:55). This is a new interview with Cimber in which he reflects on the film’s enduring popularity; he suggests that the film attracts people who may have been abused as children. ‘I look in their eyes and I get the feeling that this film really touched them’, he says. Cimber explains the circumstances by which the film’s negative was destroyed, and he praises Arrow’s diligence ‘in finding a print that worked’.

Featurettes:

- ‘Tides and Nightmares’ (23:28). This new featurette focusing ont eh production of the film features input from Matt Cimber, Dean Cundey, Millie Perkins and actor John Godd. Cimber discusses how he received the script for the film and his original response to it. Perkins’ husband Robert Thom wrote the script for her, and Cimber felt that ‘the only way it was going to work was that in the end […] you had to feel something for her [Perkins’ character] […] a kind of sympathy’. Consequently, it was important to cast an actress in whom the audience could invest their sympathy. Perkins’ trick was to ‘maintain that warmth as a person and slaughter people’. Cundey’s photography is discussed in some detail, and Cundey talks about the use of special anamorphic lenses that were designed to be used ‘on any camera’, including the three Arriflexes that Cundey used at the time of the film’s production. Cimber was reticent owing the fact that these lenses were more expensive, but Cundey convinced him that ‘the production value that they add’ made them worth the investment. ‘What I liked about it [the use of these lenses] was that I could stage movement without constant cuts at the time’, Cimber concedes. Goff and Cimber also talk extensively about the shooting of the flashbacks to Molly’s childhood.

- ‘Maiden Voyage’ (36:15). This featurette, which was previously included on Subversive’s 2004 DVD release of the film, includes interviews with Cimber, Cundey and Perkins. There’s quite a lot of overlap with Arrow’s newly produced ‘Tides and Nightmares’ featurette, with ‘Maiden Voyage’ covering much of the same ground, including the origins of the script and how Cimber approached its staging.

DISC TWO: The Premonition DISC TWO: The Premonition

- Optional introduction by Stephen Thrower (3:17)

Stephen Thrower’s introduction to The Premonition highlights the tendency in American horror films of the 1970s to confront adult themes (for example, the loss of a child), as compared with the teen focus of American horror films of the following decade. Thrower also underscores The Premonition’s focus on parapsychology, a theme that would take more prominence in De Palma’s Carrie and a number of subsequent horror pictures.

- Audio commentary with director-producer Robert Allen Schnitzer. Carried over from Media Blaster’s 2005 DVD release of The Premonition, this commentary. Schnitzer offers some strong reflections on the production of the film and some of the reasons for the choices he made in the production. It’s a good commentary; sometimes Shnitzer falls into the trap of simply describing what’s on the screen, but nevertheless he offers some very strong anecdotes about the production and his motives for making the film.

- ‘Pictures from a Premonition’ (21:19). Here, Robert Allen Schnitzer, the film’s composer Henry Mollicone and cinematographer Victor Milt talk about the film. The three participants are interviewed separately. Schnitzer reveals that the film was shot under the title ‘Turtle Heaven’ and based on a screenplay called ‘The Adoption’. Schnitzer talks about his first film, the Stallone picture Rebel. The Premonition tapped into Schnitzer’s longstanding fascination with psychic phenomena. Schnitzer reflects on the logistics of making a picture such as The Premonition, which was shot over three months in Jackson, Mississippi. Milt talks about his origins as a still photographer before progressing into the world of cinematography in his late twenties. Milt discusses the equipment he used during the production of the film and his desire to handhold cameras during the shooting of the picture. Milt suggests that being pressed for budget, time, equipment and cast/crew and having to think on your feet ‘will lead to the very best parts of any movie’ – rather than working ‘by the book’. Schnitzer claims that he tried where possible to have violence taking place offscreen, as in the sequence that depicts Jude’s murder of Andrea; this was owing to his liking for Greek theatre. Within the editing of this featurette, there’s amazing use of contact sheets containing stills shot on the set of the picture, and Polaroids also shot on the film’s set.

- Interview with Robert Allen Schnitzer (5:51). This is an older interview with Schnitzer, from Media Blasters’ previous DVD release, in which he talks about his love of parapsychology. He talks about the ways in which the finished film differs from the original script, which didn’t include the paranormal elements that Schnitzer incorporated into the picture.

- Interview with actor Richard Lynch (16:06). In another interview from Media Blasters’ DVD release of The Premonition, Lynch talks about his philosophy of acting. He discusses the qualities of The Premonition and Schnitzer’s handling of the picture. ‘Stage is an actor’s medium, and film is a director’s medium’, Lynch says, arguing that film is ‘very technical, and yet very artistic at the same time’. This is an excellent interview in which Lynch makes some very bold yet heartfelt assertions about the nature of acting and filmmaking.

- Three short films by Robert Allen Schnitzer: ‘Terminal Point’ (40:45), ‘Vertical Equinox’ (30:09) and ‘A Rumbling in the Land’ (11:06). All three films are presented in thee 1.33:1 aspect ratio. ‘Terminal Point’ and ‘A Rumbling in the Land’ are presented in monochrome; ‘Vertical Equinox’, made when Schnitzer was just seventeen, was shot in colour.

- Peace Spots (3:38). Presented in monochrome and colour, these spots made for the ‘Film Industry for Peace’ group offer arguments against the continuation of the war in Vietnam.

- Trailer (2:23) and TV Spots (3:27)

DISC THREE: Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood DISC THREE: Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood

- Optional introduction by Stephen Thrower (3:41)

In his introduction to Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood, Thrower highlights the film’s status as a ‘lost’ film: after its original release, it ‘disappeared’ and only resurfaced for a DVD release in 2003. It’s the sole feature film by its director, Christopher Speeth, and Thrower foregrounds the picture’s carnival setting and the fact that the film relies very little on conventional narrative tropes: as Thrower argues, it’s a film of psychedelic disorientation, delirium and a strong sense of place in terms of its depiction of an out-of-season carnival. Ultimately, for Thrower, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood ‘rests chiefly on its images and its visual ideas’.

- Audio commentary with critic Richard Harland Smith. Smith is an unapologetic fan of the picture and claims to ‘love every frame, every sidebar’. He discusses in some detail the different films which open with Tarot readings. Smith’s discussion of the film is packed with detail, exploring the film’s sense of location and the historical import of the Willow Grove Park. There are some periods of silence, but for the most part this is a lively, informative commentary track that is characterised by an infectious enthusiasm for the film under discussion.

- ‘The Secrets of Malatesta’ (14:06). In this new interview with the film’s director Christopher Speeth, Speeth reflects on the origins of the project that became Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood. He discusses the locations used for the film, including Willow Grove Park, which was ‘in its death throes’ and only lasted for another year or so after the film was shot there. The site is now a shopping centre, Speeth tells us. Speeth reflects on the casting of the picture, with a number of the actors being associated with ‘off Broadway’ productions. He discusses the contributions of many of the cast members, including Herve Villechaize. Speeth offers an anecdote about Villechaize stealing the negative for a picture on which, to Villechaize’s chagrin, he had been dubbed. Speeth also talks about the film’s photography, and the difficulties in shooting the picture using a heavy Mitchell camera, which meant that the setups sometimes took longer than Speeth would have liked. He also discusses the editing of the picture and the difficulties of putting the film together owing to the photography. When the film was submitted to the MPAA, ‘they made us take out all of the cannibalism’ in order to achieve an ‘R’ rating.

- ‘Crimson Speak’ (11:49). Here, in a new interview, the film’s writer Werner Liepolt reflects on his career and how he came to write Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood. Liepolt was interested in the ‘grotesquerie’ of the American carnival and also wanted to integrate into the project the legends surrounding Sawney Bean. Liepolt suggests that his story was ‘very structured’ but was represented in a much more ‘loose’ fashion on screen. He discusses the connotations of the carnival and its association with ‘death and resurrection’, showing a cognisance of the symbolic weight of the film’s setting; horror films, for Liepolt, are a medium through which potent cultural anxieties may be explored and resolved.

- ‘Malatesta’s Underground’ (10:11). Interviewed separately, the film’s art directors Richard Stange and Alan Johnson discuss their work on the picture. They were convinced to work on the film when Speeth suggested that ‘it’s not easy to make a horror film: scaring people is very, very difficult’. Most of the interiors were shot at a warehouse ‘that made steel parts’: this was used predominantly for the sequences set beneath the amusement park.

- Outtakes (2:59). This is a montage of footage, mostly depicting acts of cannibalism and violence, which would seem to be the material removed from the film in order for it to receive an ‘R’ rating from the MPAA.

- Gallery (0:38). This contains both onset stills and promotional imagery.

Retail copies find all three discs housed in their own Amaray case with reversible sleeve artwork.

Overall

Arrow’s American Horror Project Vol 1 set contains a trio of films that, at first glance, may appear divers but which are all linked by the juxtaposition of the domestic sphere (the family) with the faded glory of locations associated with leisure and tourism – each of which contains elements of the carnivalesque (the traveling carnival of The Premonition, the static carnival of Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood, and the rundown seaside locations of The Witch Who Came from the Sea). Each of the films has its own strengths: The Witch Who Came from the Sea is perhaps the strongest of the three pictures here, and where that film and The Premonition are fairly ‘straight’ pictures (in terms of their technique and narrative construction) which feature the subconscious bubbling to the surface in the form of bizarre hallucinations and nightmarish moments of analepsis, Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood is a film that is haunted thoroughly by the logic of dreams and nightmares. The presentation of all three films is satisfyingly organic and filmlike – the wear and tear to the source prints gives them a sense of authenticity. Furthermore, the three films are supported with some excellent contextual material. Truly, this is an amazing release, and even though it’s still very early in 2016, for this reviewer Arrow’s American Horror Project Vol 1 set is already clearly one of the best releases of the year. More of this, please, Arrow!

References:

Bansak, Edmund G, 1995: Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career. London: McFarland & Company

Thrower, Stephen, 2008: Nightmare USA: The Untold Story of the Exploitation Independents. Surrey: FAB Press (Second Edition)

Larger screen grabs:

The Premonition

Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood

The Witch Who Came from the Sea

|