|

The Film

Audition (Miike Takashi, 1999) Audition (Miike Takashi, 1999)

A ‘breakout’ film that unarguably elevated the profile of extraordinarily prolific filmmaker Miike Takashi within the UK and the US, Audition (1999) was a shocking film to watch upon its initial release in 1999/2000. The film has a real fin-de-siècle sensibility, and its abrupt shifts in tone (and genre) at around three quarters of an hour into its running time invite comparisons with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). However, as with Psycho, it’s probably difficult for today’s viewers to watch Audition ‘cold’, without cognisance of its shocking ‘twist’ which is signaled in a scene that demonstrates an extraordinary coup de théâtre.

The film begins with the death of Ryoko (Matsuda Miyuki), wife of Aoyama Shigeharu (Ishibashi Ryo), a documentary filmmaker, and mother of the young Shigehiko (Sawaki Tetsu). Seven years later, Shigehiko is now a teenager, and both he and Aoyama live settled but lonely lives. Shigehiko suggests to his father that he should perhaps remarry, and Aoyama relays this suggestion in a conversation with his friend Yoshikawa (Kunimura Jun), a casting director. Yoshikawa suggests that he stage auditions which will serve a dual purpose: finding an actress to star in the feature film to which he is attached, and helping Aoyama to find a prospective wife. Aoyama agrees; he is reluctant at first, but when he catches sight of one of the women in the auditions, former ballet dancer Yamazaki Asami (Shiina Eihi), he becomes besotted.

Miike’s beginnings were in direct-to-video productions (‘V-Cinema’) in 1991; this form taught Miike to work with extraordinary efficiency, making the most of the resources available to him in terms of both time and money. The world of ‘V-Cinema’ also afforded Miike a good deal of creative freedom, the lower budgets of these direct-to-video productions providing Miike with less restrictions (both creatively, and more specifically, in terms of censorship). From this, Miike seemed to foster a tendency to push boundaries, resulting in films – even ‘bigger’ pictures such as Audition, shot on film for theatrical distribution – that challenged their audiences and potentially invited the wrath of local censors everywhere. As a consequence, a number of Miike’s films (notably Ichi the Killer, 2001) encountered problems when submitted to the BBFC for classification. The controversies surrounding a small handful of his films have, for English-language audiences, arguably overshadowed his remarkably diverse body of work. As all of this may suggest, Miike is arguably the very definition of a true ‘auteur’ filmmaker. Miike’s beginnings were in direct-to-video productions (‘V-Cinema’) in 1991; this form taught Miike to work with extraordinary efficiency, making the most of the resources available to him in terms of both time and money. The world of ‘V-Cinema’ also afforded Miike a good deal of creative freedom, the lower budgets of these direct-to-video productions providing Miike with less restrictions (both creatively, and more specifically, in terms of censorship). From this, Miike seemed to foster a tendency to push boundaries, resulting in films – even ‘bigger’ pictures such as Audition, shot on film for theatrical distribution – that challenged their audiences and potentially invited the wrath of local censors everywhere. As a consequence, a number of Miike’s films (notably Ichi the Killer, 2001) encountered problems when submitted to the BBFC for classification. The controversies surrounding a small handful of his films have, for English-language audiences, arguably overshadowed his remarkably diverse body of work. As all of this may suggest, Miike is arguably the very definition of a true ‘auteur’ filmmaker.

Though it’s not really a horror film but rather a hybrid of a number of genres, the impact of Audition overshadowed Miike’s exceptionally broad body of work, leading to the perception for UK/US audiences that Miike was ‘a purveyor of viscerally-shocking horror movies’ (Berra, 2012: 65). In a piece about Ki-Duk Kim’s The Isle (2004) in Sight & Sound, Richard Falcon wrote slightly disparagingly that both Ki-Duk’s film and Audition are ‘gross-out movie[s] in arthouse clothing’ (Falcon, quoted in Shin, 2009: 94). However, for others Miike’s films offer ‘an overtly political cinema’ that challenges ‘the complacent cinema of the studio system […] through an aesthetic of “excess” and “a politic of aggression”’; they are films which are not only ‘aesthetically extreme’ but which also ‘comprise a radical critique of social values and norms’ (Richard Hyland, cited in Choi & Wada-Marciano, 2009: 11-2). Steffen Hantke, discussing Miike’s Audition in detail, highlights the cross-cultural appeal of Miike’s films, suggesting that Audition demonstrated ‘success with a variety of different audiences’ and ‘an ability to cross social and national boundaries: from popular entertainment to arthouse cinema, and from Japan to the West’ (Hantke, 2005: 55). Meanwhile, Miike himself professes little interest in deliberately attempting to court non-Japanese audiences: ‘I have no idea what goes on in the minds of people in the West and I don’t pretend to know what their tastes are. And I don’t want to start deliberately thinking about that. It’s nice that they liked my movie, but I’m not going to start deliberately worrying about why or what I can do to make it happen again’ (Miike, quoted in ibid.). This nonchalance is a part of Miike’s aesthetic: Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton note that Miike’s films have a ‘bold style: hard-hitting, flamboyant, nihilist, and above all, “cool”’ (Mathijs & Sexton, 2012: np). However, this nihilism is superficial: Mathijs and Sexton cite Aaron Gerow’s assertion that Miike’s films ‘offer a veil of superficiality that cloaks a visceral politics of diversity’ (ibid.).

Audition is in many ways an exploration of the impact of grief and its stultifying effects on the lives of those who experience it most deeply. Aoyama’s decision to look for a new wife is set in motion by a suggestion from his son Shigehiko, and Aoyama connects with Asami owing to a perception that they share a sense of loss – Asami’s ‘loss’ of her dancing career, Aoyama believes, mirroring Aoyama’s loss of his wife. ‘In a sense, it was similar to accepting death. To live means to approach death gradually. I have learned that from my own experience’, Asami suggests in her application for the audition process and in reference to the collapse of her planned career as a ballet dancer; in these words, Aoyama looks for echoes of his feelings following the death of his wife, something which is reinforced by a brief, almost subliminal shot of Ryoko sitting up in her hospital deathbed. (It’s a shot that’s reminiscent of William Friedkin’s almost subliminal cutaway to the shot of Karras’ mother in bed during the buildup to the climax of The Exorcist, 1973.) In a very early scene, Aoyama and Shigehiko are fishing together; their dialogue hints at Aoyama’s reluctance to ‘move on’ following Ryoko’s death. ‘No luck, dad?’, Shigehiko asks Aoyama, in reference to his fishing. ‘You don’t understand’, Aoyama tells his son, ‘I prefer the really big fish’. ‘I prefer real girls to imaginary fish’, Shigehiko quips, drawing the subtext of the conversation – the use of fishing as a metaphor for the search for romantic relationships – into the open. ‘When you get older, you’ll understand about love’, Aoyama offers. However, with a great deal of irony the film suggests that Aoyama, despite his age, understands very little about love – or at least, modern relationships. Aoyama’s desire for Asami allows himself to be drawn into her web; his wish to see, within her, echoes of his own grief and assuage his loneliness lead him to becoming her next victim. Audition is in many ways an exploration of the impact of grief and its stultifying effects on the lives of those who experience it most deeply. Aoyama’s decision to look for a new wife is set in motion by a suggestion from his son Shigehiko, and Aoyama connects with Asami owing to a perception that they share a sense of loss – Asami’s ‘loss’ of her dancing career, Aoyama believes, mirroring Aoyama’s loss of his wife. ‘In a sense, it was similar to accepting death. To live means to approach death gradually. I have learned that from my own experience’, Asami suggests in her application for the audition process and in reference to the collapse of her planned career as a ballet dancer; in these words, Aoyama looks for echoes of his feelings following the death of his wife, something which is reinforced by a brief, almost subliminal shot of Ryoko sitting up in her hospital deathbed. (It’s a shot that’s reminiscent of William Friedkin’s almost subliminal cutaway to the shot of Karras’ mother in bed during the buildup to the climax of The Exorcist, 1973.) In a very early scene, Aoyama and Shigehiko are fishing together; their dialogue hints at Aoyama’s reluctance to ‘move on’ following Ryoko’s death. ‘No luck, dad?’, Shigehiko asks Aoyama, in reference to his fishing. ‘You don’t understand’, Aoyama tells his son, ‘I prefer the really big fish’. ‘I prefer real girls to imaginary fish’, Shigehiko quips, drawing the subtext of the conversation – the use of fishing as a metaphor for the search for romantic relationships – into the open. ‘When you get older, you’ll understand about love’, Aoyama offers. However, with a great deal of irony the film suggests that Aoyama, despite his age, understands very little about love – or at least, modern relationships. Aoyama’s desire for Asami allows himself to be drawn into her web; his wish to see, within her, echoes of his own grief and assuage his loneliness lead him to becoming her next victim.

Aoyama’s loneliness, Miike suggests, isn’t an isolated case: Asami presumably has a number of past victims, including the owner of the nightclub that in her ‘audition’ Asami claims to have been her last place of employment, and who is seen – his feet, tongue and several fingers removed by Asami – in a bag in Asami’s place of residence. ‘Everyone in Japan is lonely’, Yoshikawa tells Aoyama when Aoyama reveals that Shigehiko has suggested he search for a new wife. ‘Are you?’, Aoyama asks his friend. ‘Aren’t you?’, Yoshikawa replies enigmatically. Later, Aoyama and Yoshikawa meet in a hotel bar and hold a conversation about economics that, in its deliberate delivery, is loaded with double meaning. ‘It’s a game of survival’, Yoshikawa says, ‘an endurance test’; ostensibly, he’s talking about the current state of filmmaking, but his words seem to apply to relationships and to life itself.

For some critics, Audition is a ‘feminist’ revenge picture which, through Asami’s violence towards Aoyama and other men who seek to contain and control her – either maliciously or incidentally – narrativises a backlash against patriarchy. Barry Keith Grant suggests that by depicting Aoyama ‘as a common, seemingly decent fellow’, Audition differs ‘from the rape-revenge formula’ of American film such as Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45 (1981) (Grant, 2007: 12). Grant suggests that the ‘target’ of Audition is the ‘masculinist, patriarchal assumptions’ of Aoyama, and his ‘attempt to commodify women […] and at the same time keep her tied to a traditional notion of Japanese femininity as obsequious and subservient’ (ibid.). The film contrasts Asami’s reserved character, codified as ‘traditional’, with the brashness of some of the other young women within the film; Aoyama and Yoshikawa express a preference for the latter. Yoshikawa ‘approves’ of his son’s girlfriend because she positions herself as meek and subservient. Meanwhile, in the hotel bar early in the film, Aoyama and Yoshikawa spot some young women giggling loudly, and in response to this Yoshikawa declares ‘Awful girls, common, full of themselves’. ‘Where are the nice ones?’, Aoyama asks jokingly. ‘Japan is finished’, Yoshikawa answers morosely. Later, after Yoshikawa has suggested to Aoyama that they hold auditions in order to find a bride for Aoyama, Aoyama says that his ideal woman would ‘be clever, well-mannered, good-natured, and accomplished in traditional arts. Someone you’d like for your son’. Male viewers, in Grant’s interpretation of Audition, are put in a position where they might ‘enjoy the sight of female subservience for over an hour’ before Miike demands that they ‘pay for it’ (ibid.). For some critics, Audition is a ‘feminist’ revenge picture which, through Asami’s violence towards Aoyama and other men who seek to contain and control her – either maliciously or incidentally – narrativises a backlash against patriarchy. Barry Keith Grant suggests that by depicting Aoyama ‘as a common, seemingly decent fellow’, Audition differs ‘from the rape-revenge formula’ of American film such as Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45 (1981) (Grant, 2007: 12). Grant suggests that the ‘target’ of Audition is the ‘masculinist, patriarchal assumptions’ of Aoyama, and his ‘attempt to commodify women […] and at the same time keep her tied to a traditional notion of Japanese femininity as obsequious and subservient’ (ibid.). The film contrasts Asami’s reserved character, codified as ‘traditional’, with the brashness of some of the other young women within the film; Aoyama and Yoshikawa express a preference for the latter. Yoshikawa ‘approves’ of his son’s girlfriend because she positions herself as meek and subservient. Meanwhile, in the hotel bar early in the film, Aoyama and Yoshikawa spot some young women giggling loudly, and in response to this Yoshikawa declares ‘Awful girls, common, full of themselves’. ‘Where are the nice ones?’, Aoyama asks jokingly. ‘Japan is finished’, Yoshikawa answers morosely. Later, after Yoshikawa has suggested to Aoyama that they hold auditions in order to find a bride for Aoyama, Aoyama says that his ideal woman would ‘be clever, well-mannered, good-natured, and accomplished in traditional arts. Someone you’d like for your son’. Male viewers, in Grant’s interpretation of Audition, are put in a position where they might ‘enjoy the sight of female subservience for over an hour’ before Miike demands that they ‘pay for it’ (ibid.).

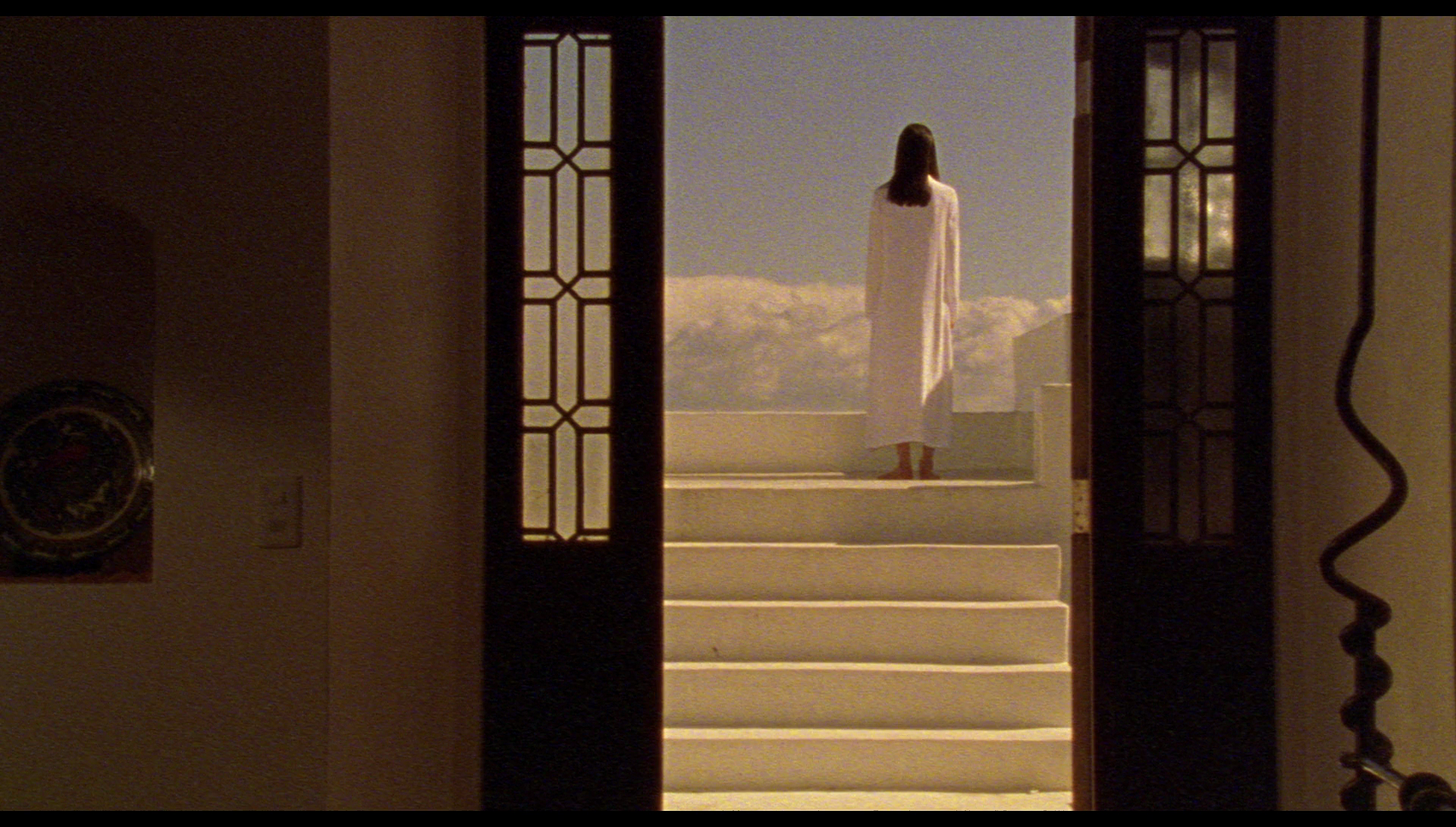

This interpretation has been pooh-poohed by Tom Mes, who suggests that the character of Asami is much too complex to be seen as the ‘immaculate, victimised foil’ which such a reading of the film would require (Mes, quoted in Hyland, 2009: 204-5). When Asami enters the audition, dressed completely in white, Miike foregrounds selfconsciously the ways in which she is objectified by Yoshikawa and Aoyama: the chair on which she (and the other auditionees) sits is placed in the centre of the frame, upon a highly polished floor which reflects the chair and the person sitting upon it – something emphasised by the composition – and in front of a desk behind which Aoyama and Yoshikawa sit, their collective gaze directed at Asami. Asami plays to the gallery, suggesting in her comments that she is frugal, learned and traditional: ‘I can cope if I’m not extravagant’, she says in reference to her earnings as a bargirl, ‘I don’t want to be poor, but I’m happy if I can afford to buy books and CDs’. She unnerves Yoshikawa, who tells Aoyama ‘She makes me nervous [….] I feel anxious [….] I can’t put my finger on it’. (Aoyama tells his friend not to worry about him: ‘I’m not a child’, Aoyama declares before adding, in words whose ironic content will gradually be revealed to the film’s viewer, ‘I trust my own judgement better than anyone else’s. If she causes trouble, I can handle it’.) When Aoyama pursues Asami, she adopts her behaviour to conform to what he expects from a woman: ‘You may think I’m a clingy woman, but I’ve been waiting for you to call’, she tells him meekly. However, when Aoyama and Asami make plans to meet at a seaside hotel, in the bedroom he babbles nervously whilst she gets undressed and, eventually, takes the active role, seducing Aoyama.

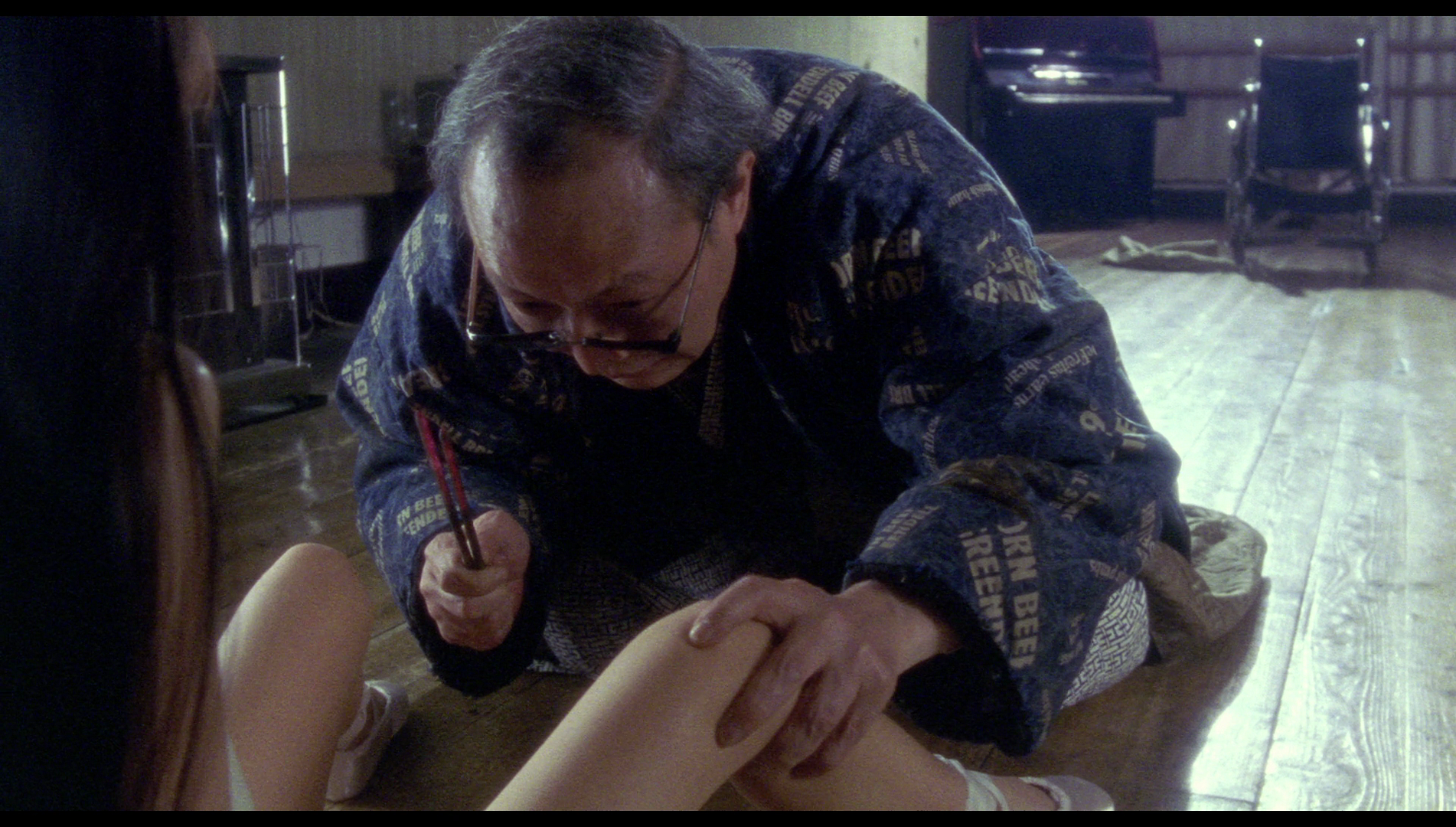

It has sometimes been linked to the ‘torture porn’ phenomenon which followed the commercial success of James Wan’s Saw in 2004, but Audition sits uneasily alongside those more exploitative pictures. For much of its running time, Miike’s film gives its viewer the impression that s/he is watching a romantic drama, before shifting gears dramatically – in a manner comparable to Psycho – at around forty-five minutes into its running time. Aoyama’s meetings with Asami build towards a nightmare of violence, enacted in an extended sequence in which Asami tortures Aoyama with horrendous cruelty; the sequence is framed in a manner which, some have claimed, offers suggestions that it may be a nightmare – Aoyama’s masochistic fantasies of punishment for his infatuation with Asami. It has sometimes been linked to the ‘torture porn’ phenomenon which followed the commercial success of James Wan’s Saw in 2004, but Audition sits uneasily alongside those more exploitative pictures. For much of its running time, Miike’s film gives its viewer the impression that s/he is watching a romantic drama, before shifting gears dramatically – in a manner comparable to Psycho – at around forty-five minutes into its running time. Aoyama’s meetings with Asami build towards a nightmare of violence, enacted in an extended sequence in which Asami tortures Aoyama with horrendous cruelty; the sequence is framed in a manner which, some have claimed, offers suggestions that it may be a nightmare – Aoyama’s masochistic fantasies of punishment for his infatuation with Asami.

There are some delicious moments of ambiguity within the picture. The relationship between Aoyama and his female assistant is complicated by her awkwardness in declaring that she is to be married and the strange glances that exist between the two: Miike may be suggesting that the assistant is uncomfortable sharing her happiness with her male colleague owing to her cognisance of how his life has been ruled by grief, or as some critics have suggested there may be the hint of a concealed affair between the two. Throughout the film, Shigehiko displays a fascination with dinosaurs that Miike returns to time and time again; the repetition of this suggests that the dinosaurs and Shigehiko’s interest in them has some narrative or symbolic importance, but this isn’t pinpointed with any accuracy. Certainly, elements such as this offer room for thought and interpretation amongst the film’s viewers.

Video

Audition is presented here uncut, in a new 2k restoration with a running time of 115:27 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 29Gb of space on the disc. The source for the restoration was a 35mm interpositive. Colours are beautiful and rich, and contrast is deep and even. There’s some very good use of chiaroscuro lighting in the opening hospital scene, for example, and this is communicated very well in this presentation. Some sequences have a haziness owing to the diffuse lighting used during production, and this presentation carries those sequences nicely too. There’s a slight softness to the image at times (perhaps owing to the interpositive that was the source for this presentation), but the image is clear and the 35mm photography has a natural, organic structure to it which is carried well in the encode. Audition is presented here uncut, in a new 2k restoration with a running time of 115:27 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 29Gb of space on the disc. The source for the restoration was a 35mm interpositive. Colours are beautiful and rich, and contrast is deep and even. There’s some very good use of chiaroscuro lighting in the opening hospital scene, for example, and this is communicated very well in this presentation. Some sequences have a haziness owing to the diffuse lighting used during production, and this presentation carries those sequences nicely too. There’s a slight softness to the image at times (perhaps owing to the interpositive that was the source for this presentation), but the image is clear and the 35mm photography has a natural, organic structure to it which is carried well in the encode.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless DTS-HD MA 5.1 track (in Japanese, naturally). This is rich and clear throughout, with excellent range. The optional English subtitles are easy to read and free of errors.

Extras

The disc includes an optional introduction by Miike (1:15). This has appeared on a previous DVD release of the film. Visibly nervous, the meek Miike looks back fondly on Audition, calling the film ‘well-crafted’ and suggesting it ‘represents an interesting turning point in Japanese cinema’. Miike speaks in Japanese, and English subtitles are provide. The disc includes an optional introduction by Miike (1:15). This has appeared on a previous DVD release of the film. Visibly nervous, the meek Miike looks back fondly on Audition, calling the film ‘well-crafted’ and suggesting it ‘represents an interesting turning point in Japanese cinema’. Miike speaks in Japanese, and English subtitles are provide.

Alongside this are included:

- an audio commentary with Miike and Daisuke Tengan. This commentary is in Japanese with English subtitles. Miike and Daisuke, the film’s writer, reflect on the process of writing the film, adapting for the screen the 1997 novel by Murakami Ryu. There’s some interesting reflection on the relationships between Japanese cinema and Hollywood, and the commentators comment on the shooting of Audition in some detail whilst also engaging with the film’s reception.

- an audio commentary with Tom Mes. This commentary with the author of the excellent book Agitator: The Cinema of Takashi Miike situates Audition within the context of Japanese cinema more generally. Mes explores the film in some depth, reflecting on its themes and discussing Miike’s approach to filmmaking.

A number of interviews are included:

- Miike Takashi (30:06). In this newly-filmed interview, Miike begins by asserting that ‘film is very important to my career’. He suggests that he is slightly bewildered by which films of his find an international audience and talks about the extent to which he believed that only Japanese audiences would ‘understand’ Aoyama’s feelings within the picture. The film was made from Miike’s ‘own desire to just make it’, and Miike suggests that though he doesn’t worry too much about audiences before making a picture, he thinks even less about potential international audiences for his films. He suggests that though ‘many people’ consider him as ‘a director of horror and violence’, this aspect of his output is a relatively small percentage of the total number of pictures that he’s made, and the perception of Miike as a director of those types of films is owing to the audience choosing to focus on them and international distributors marketing those pictures as characteristic of Miike’s output generally. The interview is in Japanese with forced English subtitles. - Miike Takashi (30:06). In this newly-filmed interview, Miike begins by asserting that ‘film is very important to my career’. He suggests that he is slightly bewildered by which films of his find an international audience and talks about the extent to which he believed that only Japanese audiences would ‘understand’ Aoyama’s feelings within the picture. The film was made from Miike’s ‘own desire to just make it’, and Miike suggests that though he doesn’t worry too much about audiences before making a picture, he thinks even less about potential international audiences for his films. He suggests that though ‘many people’ consider him as ‘a director of horror and violence’, this aspect of his output is a relatively small percentage of the total number of pictures that he’s made, and the perception of Miike as a director of those types of films is owing to the audience choosing to focus on them and international distributors marketing those pictures as characteristic of Miike’s output generally. The interview is in Japanese with forced English subtitles.

- Ishibashi Ryo (16:14). This interview has appeared on one of the film’s previous DVD releases. Ishibashi discusses his work as a musician and then his later career as an actor. He discusses his feelings about Audition and the casting of the picture, and reflects on the response it’s received both in Japan and overseas. This interview is in Japanese with forced English subtitles.

- Shiina Eiha (20:09). This interview has appeared on one of the film’s previous DVD releases. Shiina talks about her career as a model and how she came to be involved in Audition. A fan of Kurosawa Kiyoshi and Kitano Takeshi, Shiina discusses her feelings towards Miike’s work and reflects on her involvement in Audition. This interview is in Japanese with forced English subtitles.

- Ishibashi Renji (20:55). In another interview has appeared on one of the film’s previous DVD releases, Ishibashi Renji talks about his working relationship with Miike. The actor discusses Miike’s approach to directing an the methods Miike uses in making his films. This interview is in Japanese with forced English subtitles.

- Osugi Ren (16:26). This interview has appeared on one of the film’s previous DVD releases. Osugi reflects on his early attempts at acting and how he came to be involved in the profession. He talks about Miike’s ‘extraordinary’ ability to shoot without resting and comments on what he believes to be the unique elements of Miike’s style. This interview is in Japanese with forced English subtitles.

- Damaged Romance: An Appreciation by Tony Rayns (35:20). Here, in a new piece, Rayns comments on Miike’s career generally, and its origins in ‘V-Cinema’. Rayns reflects on Miike’s ‘Black Society Trilogy’ before engaging with Audition and talking about the film’s themes.

- Trailers: Japanese trailer (1:38) and international trailer (1:16).

- Stills gallery.

Overall

At one point in Audition, Aoyama asks his friend Yoshikawa, ‘Are you suggesting that I’m a silly old man who lost his head over a young girl?’ Ultimately, whether or not one interprets the prolonged sequence in which Asami tortures and mutilates Aoyama as a ‘fantasy’ or not, the picture is largely about grief – about Aoyama’s feelings following the death of his wife Ryoko, its impact on his relationship with Shigehiko, and his desire to find someone (Asami) onto whom he can project these feelings. The film’s final words foreground this theme, with Aoyama suggesting that ‘It’ll be hard to get over, but you’ll find life is wonderful one day. That’s why we all carry on with out lives’. At one point in Audition, Aoyama asks his friend Yoshikawa, ‘Are you suggesting that I’m a silly old man who lost his head over a young girl?’ Ultimately, whether or not one interprets the prolonged sequence in which Asami tortures and mutilates Aoyama as a ‘fantasy’ or not, the picture is largely about grief – about Aoyama’s feelings following the death of his wife Ryoko, its impact on his relationship with Shigehiko, and his desire to find someone (Asami) onto whom he can project these feelings. The film’s final words foreground this theme, with Aoyama suggesting that ‘It’ll be hard to get over, but you’ll find life is wonderful one day. That’s why we all carry on with out lives’.

Audition is an impressive, textured film. Seeing the picture on its first release, the ‘twist’ was shocking; and perhaps to viewers who are new to the film today, it’s nearly impossible to watch Audition without knowing about its shift into horror. However, this doesn’t detract from its impact. It’s a very good film – perhaps not Miike’s best, but certainly his most famous. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a highly impressive presentation of the main feature and some excellent contextual material.

References:

Berra, John, 2012: Directory of World Cinema: Japan. London: Intellect Books: 7-10

Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo, 2009: ‘Introduction’. In: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo, 2009: Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press: 1-12

Grant, Barry Keith, 2007: ‘Children of the Day: Sex, Gender, and the New Horror Film’. In: Boldt-Irons, Leslie et al (eds), 2007: Beauty and the Abject: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. New York: Peter Lang: 3-16

Hantke, Steffen, 2005: ‘Japanese Horror Under Western Eyes: Social Class and Global Culture in Miike Takashi’s Audition’. In: McRoy, Jay (ed), 2005: Japanese Horror Cinema. Edinburgh University Press: 54-65

Hyland, Robert, 2009: ‘A Politics of Excess: Violence and Violation in Miike Takashi’s Audition’. In: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo (eds), 2009: Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press: 199-218

Mathijs, Ernest & Sexton, Jamie, 2012: Cult Cinema. London: Wiley-Blackwell

Shin, Chi-Yun, 2009: ‘The Art of Branding: Tartan “Asia Extreme” Films’. In: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo (eds), 2009: Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press: 85-100

|