|

The Film

Waking Life (Richard Linklater, 2001)

After The Newton Boys in 1998, Richard Linklater took a break from filmmaking for three years before returning with Waking Life (2001). An ambitious, experimental film, Waking Life is deliriously ‘meta’ (about both cinema and life) and discards Hollywood narrative conventions whilst at the same time acknowledging within its dialogue the fallacy of cinematic narratives. Linklater also discarded the notion of conventional motion picture photography, blurring the lines between photography and animation by shooting Waking Life on digital video before the image underwent a painstaking digital rotoscoping process – a method that Linklater would return to with his 2006 adaptation of Philip K Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly. In its rejection of conventional cinematic practices, Linklater himself described Waking Life as ‘a kamikaze run at cinema’ in which ‘[w]e live or die on this one’ (Linklater, quoted in Nelson, 2001: 57). After The Newton Boys in 1998, Richard Linklater took a break from filmmaking for three years before returning with Waking Life (2001). An ambitious, experimental film, Waking Life is deliriously ‘meta’ (about both cinema and life) and discards Hollywood narrative conventions whilst at the same time acknowledging within its dialogue the fallacy of cinematic narratives. Linklater also discarded the notion of conventional motion picture photography, blurring the lines between photography and animation by shooting Waking Life on digital video before the image underwent a painstaking digital rotoscoping process – a method that Linklater would return to with his 2006 adaptation of Philip K Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly. In its rejection of conventional cinematic practices, Linklater himself described Waking Life as ‘a kamikaze run at cinema’ in which ‘[w]e live or die on this one’ (Linklater, quoted in Nelson, 2001: 57).

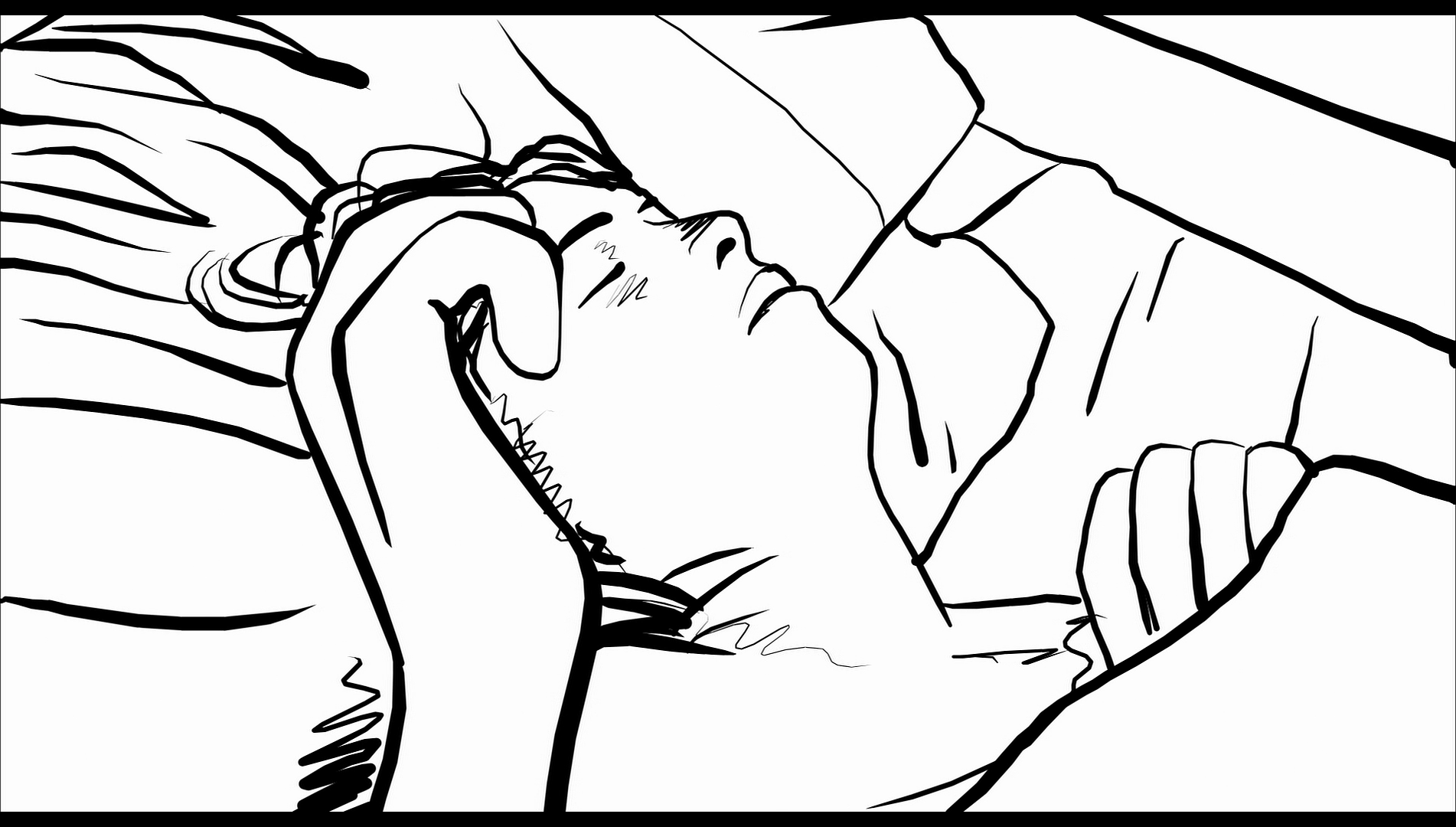

The narrative of the film is difficult to summarise because so few of the characters have names and there’s little in the way of conventional storytelling. However, the film begins with two children: a girl (played by Linklater’s daughter Lorelei Linklater) and a boy (Trevor Jack Brooks) who are playing with a cootie catcher. Following this, the film ‘proper’ begins with the nameless protagonist (Wiley Wiggins) arriving in a city via train. After alighting the train and leaving the station, he is picked up by Boat Car Guy (Bill Wise), who drives a car that is decked out like a boat; another passenger in Boat Car Guy’s vehicle gives Boat Car Guy instructions as to where Wiggins’ character should be dropped off. Stepping out of the car, the protagonist stoops in the road to pick up a piece of paper on which is written ‘Look to your right’. He does so, only to see a car hurtling towards him. From here, Wiggins’ character is shown awakening, as if from a dream. He visits a university classroom, where he listens to a lecturer (Robert C Solomon) discuss existentialism; after the class, the protagonist walks and talks with the lecturer, who tells the protagonist that ‘We should never simply write ourselves off and say we’re the victim of various forces. It’s always our decision who we are’.

As the film progresses, the protagonist wanders through various scenarios involving characters espousing different philosophical ideas; after some of these encounters, Wiggins’ character wakes as if from a dream state, only to find himself once again in another dream. Eventually, he speaks with various characters who reflect on the concept of lucid dreaming, leading the protagonist to believe himself to be within a lucid dream state. Each ‘level’ within the dream is peeled away like the layers of an onion, building towards a meeting between the protagonist and the film’s director, who is shown playing a seemingly symbolic game of pinball in the backroom of a bar As the film progresses, the protagonist wanders through various scenarios involving characters espousing different philosophical ideas; after some of these encounters, Wiggins’ character wakes as if from a dream state, only to find himself once again in another dream. Eventually, he speaks with various characters who reflect on the concept of lucid dreaming, leading the protagonist to believe himself to be within a lucid dream state. Each ‘level’ within the dream is peeled away like the layers of an onion, building towards a meeting between the protagonist and the film’s director, who is shown playing a seemingly symbolic game of pinball in the backroom of a bar

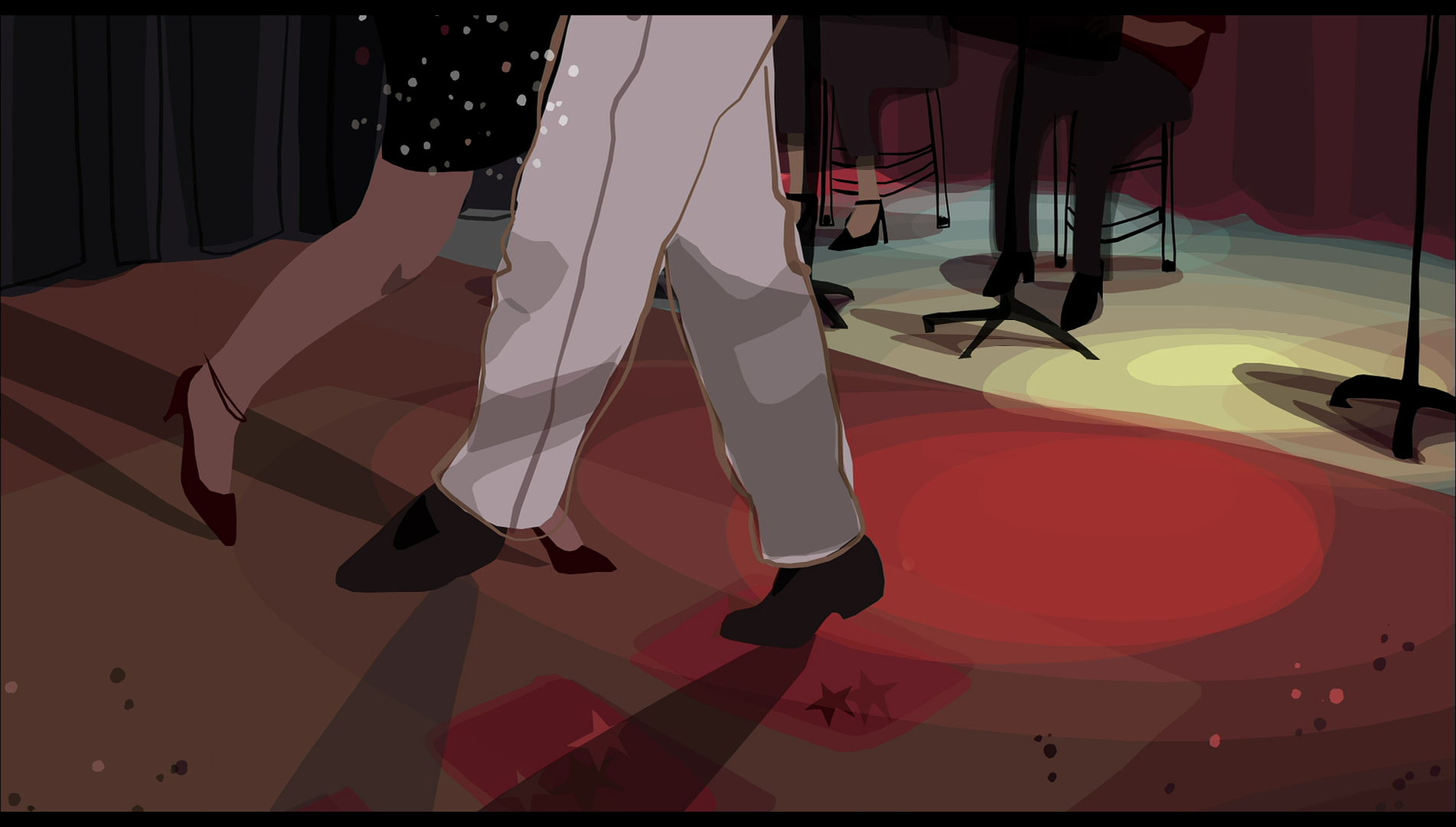

The film has an episodic structure, the protagonist’s encounters with the various characters he meets feeling very loose and disconnected. The film references the concept of lucid dreaming overtly (and in this sense, it has a strange bedfellow in the form of Christopher Nolan’s Inception, 2010). The disjointed structure of the film seems to be foregrounded by an early scene in which a musical group are shown rehearsing (they reappear later in the picture), and the lead musician interrupts their playing to assert that the music must be ‘slightly out of tune’ and both ‘rich’ and ‘detached’. This scene, which seems to offer a statement of intent for the film itself, recalls Dario Argento’s thrilling all’italiana Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1975), in which near the start of the picture the film’s protagonist Marc Daly (David Hemmings), a music teacher, interrupts his students to remind them that the jazz they are playing originated in the brothels and ‘should be more trashy’. Where this scene in Argento’s film outlines one of the film’s major themes (the contrast between the ‘respectable’ and the ‘trashy’), it also acts as a manifesto of sorts for the film itself and its celebration of (and elevation of) the stereotypically ‘trashy’ pleasures of a genre which is often derided (the whodunit). Likewise, in its suggestion through the dialogue that the music played by the group should be ‘detached’ and ‘slightly out of tune’, this similar scene near the start of Waking Life seems to provide a statement of intent for Linklater’s film, offering words that resonate with the manner in which the film uses rotoscoped animation instead of conventional photography, and also echo in relation to the film’s ‘loose’ approach to narrative.

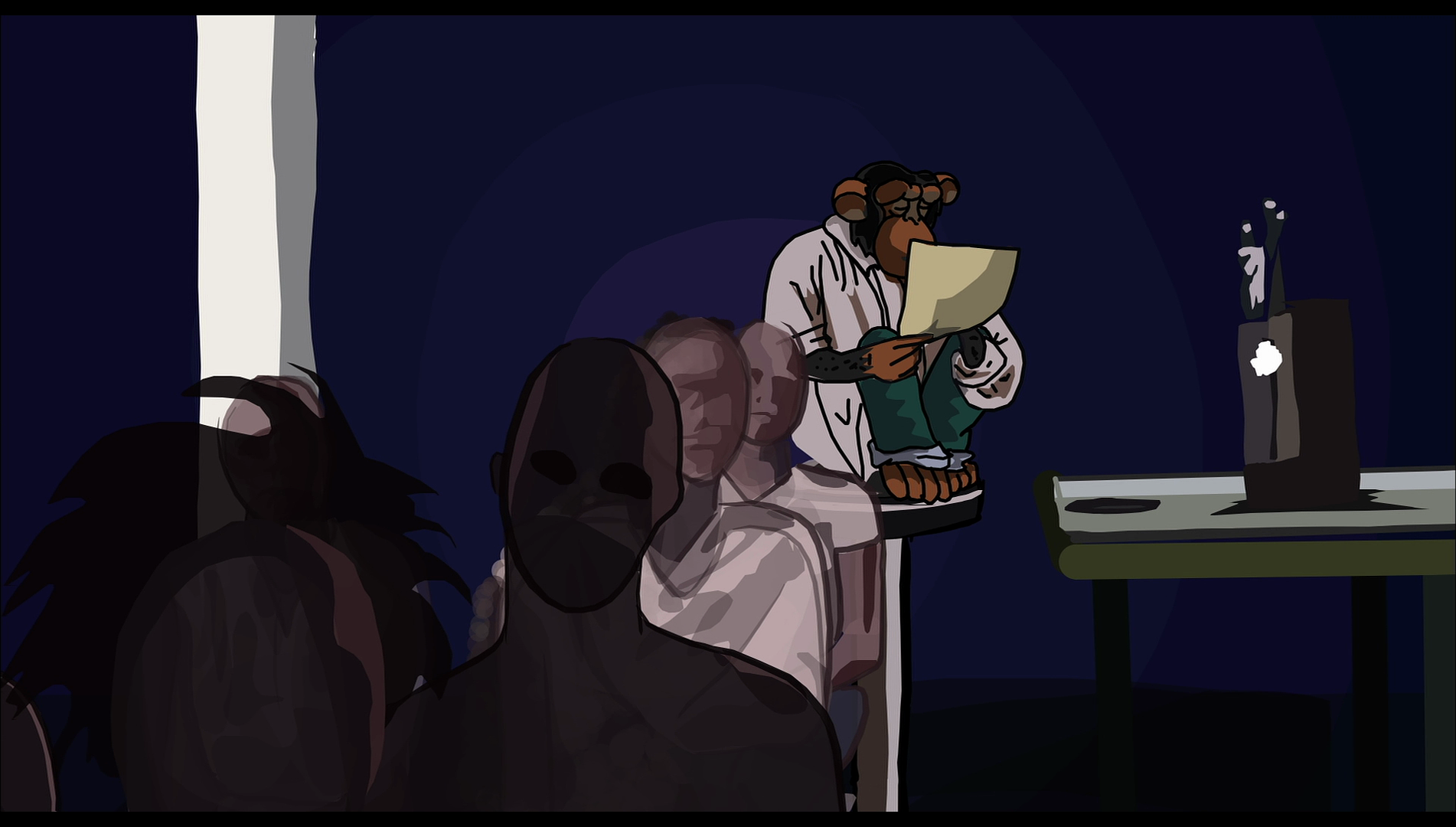

Kent Jones has described Waking Life’s structure as ‘a flowering of dreamlike encounters contained within a series of dreams that become increasingly extended and disturbingly cryptic as the film goes on, just like a night of real REM sleep’ (Jones, 2007: 77). The approach is explored in one of the scenes in the film, in which a man (Alex Nixon) and a woman (Violet Nichols) sit at a bar. The man is writing in a notebook. ‘What are you writing?’, the woman asks. ‘A novel’, he replies. ‘What’s the story?’, the woman asks. ‘There is no story’, he tells her: just gestures and emotions, ‘the greatest story ever told’. Like Linklater’s debut picture Slacker (1991), Waking Life eschews the typical structures associated with Hollywood in favour of a picaresque approach to narrative, which features Wiggins’ character encountering various other characters who express aspects of their personal philosophies with him at length. Some of these are expressed in formal terms, with direct reference to specific philosophers and their ideas; some of them are expressed much more informally. Some of these philosophies are expounded in simple conversations: many of the early sequences feature Wiggins listening to older men (and, less frequently, women) as they wax lyrical about their personal philosophies. In a smaller number of sequences, characters express their feelings about life in vignettes – as in the sequence in which Wiggins listens to a man (J C Shakespeare) who talks about self-destruction (‘a self-destructive man feels completely alienated, utterly alone’) being the defining state of modern society (‘It’s in all of us. We revel in it’) before committing an act of self-immolation (‘Let my own lack of a voice be heard’) which is ignored by the other characters within the scene. In some of these sequences, Wiggins is passive, listening to these characters and interacting with them rarely, if at all; in others, he takes a slightly more active role, engaging them in conversation. A number of sequences take place outside his perception, with the dream-within-a-dream structure suggesting that Wiggins’ character is observing these events unfold within his dream. Kent Jones has described Waking Life’s structure as ‘a flowering of dreamlike encounters contained within a series of dreams that become increasingly extended and disturbingly cryptic as the film goes on, just like a night of real REM sleep’ (Jones, 2007: 77). The approach is explored in one of the scenes in the film, in which a man (Alex Nixon) and a woman (Violet Nichols) sit at a bar. The man is writing in a notebook. ‘What are you writing?’, the woman asks. ‘A novel’, he replies. ‘What’s the story?’, the woman asks. ‘There is no story’, he tells her: just gestures and emotions, ‘the greatest story ever told’. Like Linklater’s debut picture Slacker (1991), Waking Life eschews the typical structures associated with Hollywood in favour of a picaresque approach to narrative, which features Wiggins’ character encountering various other characters who express aspects of their personal philosophies with him at length. Some of these are expressed in formal terms, with direct reference to specific philosophers and their ideas; some of them are expressed much more informally. Some of these philosophies are expounded in simple conversations: many of the early sequences feature Wiggins listening to older men (and, less frequently, women) as they wax lyrical about their personal philosophies. In a smaller number of sequences, characters express their feelings about life in vignettes – as in the sequence in which Wiggins listens to a man (J C Shakespeare) who talks about self-destruction (‘a self-destructive man feels completely alienated, utterly alone’) being the defining state of modern society (‘It’s in all of us. We revel in it’) before committing an act of self-immolation (‘Let my own lack of a voice be heard’) which is ignored by the other characters within the scene. In some of these sequences, Wiggins is passive, listening to these characters and interacting with them rarely, if at all; in others, he takes a slightly more active role, engaging them in conversation. A number of sequences take place outside his perception, with the dream-within-a-dream structure suggesting that Wiggins’ character is observing these events unfold within his dream.

In terms of abandoning conventional Hollywood models of narrative in favour of a series of philosophical dialogues and monologues, Linklater suggested that his intention was ‘to capture the way the human mind works—that accumulation-of-ideas sort of structure. That’s what the narrative of all our lives is’ (Linklater, quoted in Nelson, op cit.: 57). In reference to the episodic structure of Waking Life, Mike King has argued that ‘the speed at which the issues are run past us ensures that the film degenerates into cod philosophy’ (King, 2009: 158). King also suggests that ‘what is probably quite unintended by Linklater’ is the film’s depiction of the ‘typical young American—apparently free from any grounding necessity to make a living—who has succumbed to a quiet and pervasive depression’ (ibid.). Wiggins’ character is nameless and though, as King argues, the rotoscoping ‘completely hides the nuance of facial expression, it is obvious that the character is not happy’ (ibid.). From a European perspective, Wiggins’ character is ‘uniquely American in his New Age shrink-culture searching’ (ibid.).

Because of its episodic structure and the fact that Wiggins’ character is predominantly passive, not querying or interrogating the ideas that are expressed to him, the various ‘voices’ and philosophical within Waking Life are presented as disconnected from one another. The overall impression, then, is of life as a solipsistic endeavour: various voices collide but don’t communicate, individuals locked within their own personal philosophies. Writing about Waking Life, Jonathan Rosenbaum has described the film as ‘a lot of people talking and walking, as well as listening and sitting’: like Slacker, the film has an improvised quality (Rosenbaum, 2004: 291). The picture, for Rosenbaum, offers ‘a string of paradoxes and reflections about what’s real and what’s not, about when you’re dreaming and when you’re awake’, put together in ‘an unusual way’ that ‘seems calculated to complicate all of the issues it raises rather than resolve any of them’ (ibid.). The sense of dissociation in the dream state itself is underscored in a scene which features cameos from Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, who appear to be playing the characters (Jesse and Celine) they outlined in Linklater’s earlier film Before Sunrise (1995), in which during pillow talk they reflect on Celine’s belief that she is ‘observing [her] life from the position of an old woman about to die’. ‘I keep looking back on my life, like my waking life is her memories’, Celine suggests. Because of its episodic structure and the fact that Wiggins’ character is predominantly passive, not querying or interrogating the ideas that are expressed to him, the various ‘voices’ and philosophical within Waking Life are presented as disconnected from one another. The overall impression, then, is of life as a solipsistic endeavour: various voices collide but don’t communicate, individuals locked within their own personal philosophies. Writing about Waking Life, Jonathan Rosenbaum has described the film as ‘a lot of people talking and walking, as well as listening and sitting’: like Slacker, the film has an improvised quality (Rosenbaum, 2004: 291). The picture, for Rosenbaum, offers ‘a string of paradoxes and reflections about what’s real and what’s not, about when you’re dreaming and when you’re awake’, put together in ‘an unusual way’ that ‘seems calculated to complicate all of the issues it raises rather than resolve any of them’ (ibid.). The sense of dissociation in the dream state itself is underscored in a scene which features cameos from Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, who appear to be playing the characters (Jesse and Celine) they outlined in Linklater’s earlier film Before Sunrise (1995), in which during pillow talk they reflect on Celine’s belief that she is ‘observing [her] life from the position of an old woman about to die’. ‘I keep looking back on my life, like my waking life is her memories’, Celine suggests.

Linklater shot the picture in less than twenty-five days; the footage was then passed on to a team of animators headed by Bob Sabiston, who ‘digitally painted over every frame using his [Sabiston’s] own “interpolated rotoscoping” software’ (Nelson, op cit.: 57). This resulted in an aesthetic which has been described as ‘a lo-fi, almost sloppy style that makes everything in Waking Life seem to pulse and float’ (ibid.). Sabiston and Linklater had previously discussed collaborating on a documentary television programme which would have been animated, but this project never came to fruition (Robinson, 2010: 139). Linklater remembered Sabiston and asked him to work on Waking Life. As Chris Robinson has observed, ‘the rotoscope technique complements the ambiguous dream/reality duality of the film: it’s reality and yet it’s not’ (ibid.). The rotoscoping results in images that are, at times, detailed and almost photorealistic, and at other times crude, caricaturish and abstract: Chris Robinson describes this method by suggesting ‘the animation becom[ing] an active participant in the film in that it caricatures the characters as they speak’ (ibid.). Reinforcing the episodic quality of the film’s narrative, each sequence was animated by different artists, ‘giving each space and character a unique personality’ (ibid.). Additionally, our perception is continually destablised by having characters in the foreground and the background visibly wavering – so that the viewer may come away from the film with a feeling of motion sickness.

Robinson says that the choice to have different animators work on different sequences, ‘along with the shifting, floating, dislocated backgrounds and landscapes keeps the viewer on edge, at a distance’ (Robinson, op cit.: 139). Likewise, Kent Jones suggests that the film’s aesthetic matches its narrative structure, with both suggesting that Waking Life is ‘a movie with a brain of its own. Sometimes it feels like the brain belongs to Wiggins [or rather, his character], but his point of view keeps thinning out, expanding and dissolving into the events and landscapes he encounters’ (Jones, op cit.: 77). The overlap between the ways in which the animation of the picture shifts within each sequence, owing to the input of different animators, and each sequence’s focus on different philosophical ideas suggests, for Jones, that ‘the scary question at the heart of Waking Life’ is that ‘in the end, how important is the distinction between the world and our perception of it?’ (ibid.). The appearance of a character called Mr Debord might remind the viewer of Guy Debord and the Situationists’ privileging of psychogeography, the dérive and the flaneur – the urban wanderer and observer, who might embark on a dérive, a ‘drift’ through an urban landscape whose geography and architecture interact with the subconscious of the wanderer. These theories may be seen as forming the core of Waking Life, with Wiggins’ character being the wanderer taking part in a dérive, which begins with his arrival in a new city, and that is revealed to be taking place within a dream state (ie, his subconscious). Robinson says that the choice to have different animators work on different sequences, ‘along with the shifting, floating, dislocated backgrounds and landscapes keeps the viewer on edge, at a distance’ (Robinson, op cit.: 139). Likewise, Kent Jones suggests that the film’s aesthetic matches its narrative structure, with both suggesting that Waking Life is ‘a movie with a brain of its own. Sometimes it feels like the brain belongs to Wiggins [or rather, his character], but his point of view keeps thinning out, expanding and dissolving into the events and landscapes he encounters’ (Jones, op cit.: 77). The overlap between the ways in which the animation of the picture shifts within each sequence, owing to the input of different animators, and each sequence’s focus on different philosophical ideas suggests, for Jones, that ‘the scary question at the heart of Waking Life’ is that ‘in the end, how important is the distinction between the world and our perception of it?’ (ibid.). The appearance of a character called Mr Debord might remind the viewer of Guy Debord and the Situationists’ privileging of psychogeography, the dérive and the flaneur – the urban wanderer and observer, who might embark on a dérive, a ‘drift’ through an urban landscape whose geography and architecture interact with the subconscious of the wanderer. These theories may be seen as forming the core of Waking Life, with Wiggins’ character being the wanderer taking part in a dérive, which begins with his arrival in a new city, and that is revealed to be taking place within a dream state (ie, his subconscious).

Linklater’s intention with presenting the film in this way, by avoiding conventional motion picture photography, was to maintain audience interest regardless of the film’s abandonment of Hollywood models of narrative: ‘In live action, a movie with this much dense information might be hideously boring and unwatchable’, Linklater said in reference to the film’s structure (which involves Wiggins’ character wandering into and through various philosophical discussions), ‘But the animation makes an interesting anchor’ (Linklater, quoted in Nelson, op cit.: 57). Though the ideas presented within each sequence may on their own seem, as Kent Jones says, ‘superficial and hopelessly collegiate, a gaggle of eccentrics with big theories about the nature of existence mixing with sociopathic malcontents and inner-journeying slackers’, the cumulative effect as each theory is placed in juxtaposition with others is one of uncertainty and ‘searching’ (Jones, op cit.: 78). As Wiggins’ character awakens from each level of the dream and the film moves into its final sequence, ‘it becomes less playful, more troubling, and more mysterious’ until the final moments which offer ‘an image pitched between transcendence and terror’ (ibid.).

This final sequence begins after Wiggins’ character has listened to a middle-aged woman describe the self as ‘a place to momentarily house all the abstractions’. The woman discusses life in the past tense: ‘I loved all the people’, she asserts, ‘Looking back, that’s all that really mattered’. From here, Wiggins’ character finds himself in an idyllic park, where an elderly woman presents him with a sketch of himself. In the sketch, Wiggins’ head splits apart to reveal a dark night-time scene; the camera enters this scene, and we and Wiggins’ character listen to a man discussing Kierkegaard, before the protagonist wanders into a bar. In the bar, people are dancing to the music of a band introduced in a sequence much earlier in the narrative. Wandering into the backroom of the bar, Wiggins’ character encounters a man playing pinball. This character, played by Linklater himself, is the same man who gave the Boat Car Guy specific directions as to where Wiggins’ character should be dropped off – thus beginning his dérive. With this sequence and the way in which Linklater’s character bookends the narrative, Linklater seems to invite the film’s viewer to identify Linklater’s authorship over the film. (In this sense, the director’s cameo resembles Sam Peckinpah’s cameo at the end of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, 1973, in which Peckinpah, the film’s director, goads the protagonist Pat Garrett, played by James Coburn, into action prior to Garrett’s killing of Kris Kristofferson’s Billy the Kid.) The dreams may be those of Wiggins’ character, this cameo suggests, but they’re directed by Linklater. (In this scene, Linklater also alludes to the ideas of famed Gnostic Philip K Dick – specifically Dick’s 1974 novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said and Dick’s reflections on the novel in ‘How to Build a Universe That Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later’ – which hints at Linklater’s subsequent adaptation of Dick’s A Scanner Darkly.) This final sequence begins after Wiggins’ character has listened to a middle-aged woman describe the self as ‘a place to momentarily house all the abstractions’. The woman discusses life in the past tense: ‘I loved all the people’, she asserts, ‘Looking back, that’s all that really mattered’. From here, Wiggins’ character finds himself in an idyllic park, where an elderly woman presents him with a sketch of himself. In the sketch, Wiggins’ head splits apart to reveal a dark night-time scene; the camera enters this scene, and we and Wiggins’ character listen to a man discussing Kierkegaard, before the protagonist wanders into a bar. In the bar, people are dancing to the music of a band introduced in a sequence much earlier in the narrative. Wandering into the backroom of the bar, Wiggins’ character encounters a man playing pinball. This character, played by Linklater himself, is the same man who gave the Boat Car Guy specific directions as to where Wiggins’ character should be dropped off – thus beginning his dérive. With this sequence and the way in which Linklater’s character bookends the narrative, Linklater seems to invite the film’s viewer to identify Linklater’s authorship over the film. (In this sense, the director’s cameo resembles Sam Peckinpah’s cameo at the end of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, 1973, in which Peckinpah, the film’s director, goads the protagonist Pat Garrett, played by James Coburn, into action prior to Garrett’s killing of Kris Kristofferson’s Billy the Kid.) The dreams may be those of Wiggins’ character, this cameo suggests, but they’re directed by Linklater. (In this scene, Linklater also alludes to the ideas of famed Gnostic Philip K Dick – specifically Dick’s 1974 novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said and Dick’s reflections on the novel in ‘How to Build a Universe That Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later’ – which hints at Linklater’s subsequent adaptation of Dick’s A Scanner Darkly.)

Wiggins’ recollection of Linklater’s role at the start of the film reminds us that it was this character who began the dérive by offering specific instructions as to where the protagonist should be dropped off by Boat Car Guy; and when Wiggins’ character explains that he ‘can’t get out of it [the dream] [….] I’m starting to think that I’m dead’, Linklater tells him simply to ‘Just wake up’ – leading to another layer within the dream. Linklater’s role at the end of the film gives a layer of irony to the early discussions of existentialism, and the university lecturer’s assertion that ‘It’s always our decision who we are’: the passive role the protagonist takes within his own dream state undermines that statement. The sense of fatalism is foregrounded in the words on the cootie catcher that the children play with in the film’s opening sequence – ‘Dream is destiny’ – the ambiguous phraseology of which may be interpreted in a number of ways (for example, destiny is written in our dreams; the dream state itself is our ‘destiny’). This theme is also addressed in a sequence in which Wiggins’ character listens to a young man (David Sosa) who talks about free will, faith and quantum mechanics. This young man suggests that ‘Who you are is mostly a matter of the choices you make’, but that the notion of free will is an illusion because our actions are dictated on a molecular level by physical laws and sub-atomic particles. The young man concludes by asserting that ‘I’d rather be a gear in some big deterministic machine than just some random swerving’ (as per quantum mechanics). Wiggins’ recollection of Linklater’s role at the start of the film reminds us that it was this character who began the dérive by offering specific instructions as to where the protagonist should be dropped off by Boat Car Guy; and when Wiggins’ character explains that he ‘can’t get out of it [the dream] [….] I’m starting to think that I’m dead’, Linklater tells him simply to ‘Just wake up’ – leading to another layer within the dream. Linklater’s role at the end of the film gives a layer of irony to the early discussions of existentialism, and the university lecturer’s assertion that ‘It’s always our decision who we are’: the passive role the protagonist takes within his own dream state undermines that statement. The sense of fatalism is foregrounded in the words on the cootie catcher that the children play with in the film’s opening sequence – ‘Dream is destiny’ – the ambiguous phraseology of which may be interpreted in a number of ways (for example, destiny is written in our dreams; the dream state itself is our ‘destiny’). This theme is also addressed in a sequence in which Wiggins’ character listens to a young man (David Sosa) who talks about free will, faith and quantum mechanics. This young man suggests that ‘Who you are is mostly a matter of the choices you make’, but that the notion of free will is an illusion because our actions are dictated on a molecular level by physical laws and sub-atomic particles. The young man concludes by asserting that ‘I’d rather be a gear in some big deterministic machine than just some random swerving’ (as per quantum mechanics).

Video

Waking Life is here presented uncut, with a running time of 100:43 mins, and in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Taking up a little over 17Gb of space on its disc, Waking Life is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film was shot on mini-DV cameras and then rotoscoped, with some sequences displaying a very different animation style to others – from the photorealistic to the almost abstract. The presentation here is clear and detailed, with colour consistency and contrast levels being a big improvement over the film’s previous home video versions. It’s a rich, detailed image, certainly a very pleasing presentation.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. This is clear, rich and resonant. Voices, the sound of which guides the film, resonate, and the track shows strong range with very deep bass. It’s not a ‘showy’ mix, by any means, but the track demonstrates convincing and effective separation especially in terms of music and the film’s use of ambient sound effects.

Also provided are optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and free of errors.

Extras

The disc includes:

- an audio commentary with Linklater, Bob Sabiston, Wiley Wiggins and producer Tommy Pallotta. This commentary has been seen (or rather, heard) before, on the film’s previous DVD release. The commentators discuss the origins of the project and the ways in which they approached making this unusual picture. - an audio commentary with Linklater, Bob Sabiston, Wiley Wiggins and producer Tommy Pallotta. This commentary has been seen (or rather, heard) before, on the film’s previous DVD release. The commentators discuss the origins of the project and the ways in which they approached making this unusual picture.

- a second audio commentary by the animation team. Like the previous commentary, this track was included on the film’s prior DVD release. On this track, the commentators reflect on the process of animating the film, with the animators of each sequence discussing their work on the picture.

- a trivia track. This is an optional subtitle track, written by Linklater, which explores some of the themes and ideas contained within the film.

- a series of short films by Bob Sabiston: ‘The Trees’ (0:34), ‘God’s Little Monkey’ (2:06), ‘Project Incognito’ (20:26), ‘Color Test’ (2:47), ‘Snack and Drink’ (3:44), ‘Figures of Speech’ (30:46), ‘Grasshopper’ (14:30), ‘Ryan’s Capitol Tour’ (6:33) and ‘The Even More Fun Trip’ (22:36). These short films, a mixture of animation and live-action, are arguably as interesting as the main feature and worth the price of admission alone.

- ‘The Making of Waking Life’ (4:24). This very short featurette features Linklater talking about the origins of the project and Linklater, Sabiston and Pallatto discussing its production. Included here is some tantalizing footage from the production itself, juxtaposed with the finished animation.

- Animation Tutorial (20:22). Here, in a vintage piece, Bob Sabiston discusses the process of animating the film.

- Deleted and Alternative Scenes (7:32). This includes deleted scenes and alternate versions of some scenes, with some glimpses of alternative animation.

- Pre-Animation Footage (12:02). This fascinating piece is a montage of the footage that Linklater shot prior to Sabiston and his team animating it. (If anything, it demonstrates the shonky nature of digital video in the first few years of the new millennium.)

- Trailer (1:59).

Retail copies include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet which contains a new essay about the film by film critic David Jenkins, along with a guide to the short films of Bob Sabiston.

Overall

Waking Life is a tough film to talk about: absent of a conventional narrative, the picture features so many philosophical points of view presented by different characters that they sometimes jar and fail to connect – which is perhaps the ‘point’ of the film. As noted above, some viewers may find the film’s episodic structure and its depiction of various philosophical viewpoints as superficial and affected, but that is arguably the intention: to show how disconnected and incongruent these ideas are. One sequence suggests this: it features a group of four men (Adam Goldberg, Nicky Katt, Jason Liebrecht & Brent Green) walking along a city street, where they spot an older man (R C Whittaker) who has climbed a lamppost. ‘Stupid bastard’, one of the four men says; to this, another (Goldberg) responds, ‘No worse than us. He’s all action and no theory. We’re all theory and no action’. Perhaps more than anything, the film suggests the necessity for ideas to be accompanied by action, and for action to be directed by ideas. At several points, the film also foregrounds theories of film, with Andre Bazin being mentioned directly, and there’s the suggestion that the protagonist’s experiences within his dream state act as a metaphor for the experience of watching a film in the cinema. Waking Life is a tough film to talk about: absent of a conventional narrative, the picture features so many philosophical points of view presented by different characters that they sometimes jar and fail to connect – which is perhaps the ‘point’ of the film. As noted above, some viewers may find the film’s episodic structure and its depiction of various philosophical viewpoints as superficial and affected, but that is arguably the intention: to show how disconnected and incongruent these ideas are. One sequence suggests this: it features a group of four men (Adam Goldberg, Nicky Katt, Jason Liebrecht & Brent Green) walking along a city street, where they spot an older man (R C Whittaker) who has climbed a lamppost. ‘Stupid bastard’, one of the four men says; to this, another (Goldberg) responds, ‘No worse than us. He’s all action and no theory. We’re all theory and no action’. Perhaps more than anything, the film suggests the necessity for ideas to be accompanied by action, and for action to be directed by ideas. At several points, the film also foregrounds theories of film, with Andre Bazin being mentioned directly, and there’s the suggestion that the protagonist’s experiences within his dream state act as a metaphor for the experience of watching a film in the cinema.

Regardless of one’s feelings about Waking Life – and the film itself is sure to divide opinion amongst viewers – Arrow’s presentation of the film is tip-top and accompanied by some absolutely excellent contextual material. Linklater fans will find this to be an essential purchase. The inclusion of a good number of short films by Bob Sabiston are arguably reason enough to purchase the disc.

References

Jones, Kent, 2007: Physical Evidence: Selected Film Criticism. Wesleyan University Press

King, Mike, 2009: The American Cinema of Excess: Extremes of the National Mind on Film. London: McFarland and Company

Nelson, Bob, 2001: ‘The Dreamlife of Angels’. Spin (November, 2001): 57-8

Robinson, Chris, 2010: Animators Unearthed: A Guide to the Best of Contemporary Animation. London: Continuum

Rosenbaum, Jonathan, 2004: Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. The Johns Hopkins University Press

|