|

The Film

Black Mama, White Mama (Eddie Romero, 1972) Black Mama, White Mama (Eddie Romero, 1972)

As the legend has it, Pam Grier was working as a telephone switchboard operator when she was ‘discovered’ by AIP as an acting talent. The last in a series of WIP (Women In Prison) films that Grier made before beginning her career as a leading actress in urban ‘blaxploitation’ films, Black Mama, White Mama was one of a run of AIP-produced pictures starring Grier – which continued with Coffy (Jack Hill, 1973) and Foxy Brown (Jack Hill, 1974), and ended with ‘Sheba, Baby!’ (William Girdler, 1975) – that redefined how women (and particularly women of colour) would be represented onscreen. Mia Mask has argued that Coffy, which was to be Grier’s next film after Black Mama, White Mama, was a watershed picture that ‘served as the bridge from sexploitation to Blaxploitation’ by offering Grier her first solo starring role (Mask, 2009: 89). Black Mama, White Mama still finds Grier in a role that sees her objectified and subjected to sexual exploitation, whereas from Coffy onwards Grier’s characters would be fully aware of their own sexuality, using it to ensnare the male antagonists.

The film opens in an unidentified location in the Philippines, with a bus containing new inmates – among them two Americans, white revolutionary Karen Brent (Margaret Markov), and African-American prostitute Lee Daniels (Pam Grier) – arriving at a women’s prison. They are greeted by two female guards: Logan (Laurie Burton) and her lover Densmore (Lynn Borden). As the girls are showering, Densmore spies on them through a small hole in the wall and masturbates.

Densmore approaches Lee and offers her an easy pass if Lee will respond by sleeping with Densmore. Lee refuses. Densmore makes the same proposition to Karen, who accepts. This causes Lee and Densmore to fight, resulting in Logan throwing Densmore and Lee into ‘the box’: a metal structure under the blazing sun, in which prisoners who are to be punished are placed naked. After being released from ‘the box’, Lee and Karen are transported into the city; but on the way, the bus carrying them is intercepted by a group of guerillas with whom Karen is affiliated. The aim of the guerillas is to free Karen, but the police arrive and Karen and Lee are forced to flee together, in a separate direction from the guerillas. Chained together, Lee and Karen must fight through the wilderness and try to find a way to escape. Meanwhile, Karen and Lee are hunted by the guerillas, led by Karen’s lover Ernesto (Zaldy Zshornack), who try to track down Karen as being in contact with Karen will ensure that they get the small arms they need for their cause. Karen and Lee are also being tracked by the police, led by Captain Cruz (Eddie Garcia), who hires a local ‘fixer’ and criminal, Ruben (Sid Haig). Karen is also being sought by the pimp Vic Cheng (Vic Diaz), from whom she stole a large sum of money. (Cruz has been tasked with recapturing the women by local politician Galindo, played by Alfonso Carvajal.) Densmore approaches Lee and offers her an easy pass if Lee will respond by sleeping with Densmore. Lee refuses. Densmore makes the same proposition to Karen, who accepts. This causes Lee and Densmore to fight, resulting in Logan throwing Densmore and Lee into ‘the box’: a metal structure under the blazing sun, in which prisoners who are to be punished are placed naked. After being released from ‘the box’, Lee and Karen are transported into the city; but on the way, the bus carrying them is intercepted by a group of guerillas with whom Karen is affiliated. The aim of the guerillas is to free Karen, but the police arrive and Karen and Lee are forced to flee together, in a separate direction from the guerillas. Chained together, Lee and Karen must fight through the wilderness and try to find a way to escape. Meanwhile, Karen and Lee are hunted by the guerillas, led by Karen’s lover Ernesto (Zaldy Zshornack), who try to track down Karen as being in contact with Karen will ensure that they get the small arms they need for their cause. Karen and Lee are also being tracked by the police, led by Captain Cruz (Eddie Garcia), who hires a local ‘fixer’ and criminal, Ruben (Sid Haig). Karen is also being sought by the pimp Vic Cheng (Vic Diaz), from whom she stole a large sum of money. (Cruz has been tasked with recapturing the women by local politician Galindo, played by Alfonso Carvajal.)

Featuring a story by Jonathan Demme which he reputedly sold to AIP for the princely sum of $500, Black Mama, White Mama was shot in the Philippines, with a cast comprising both American actors and locals. Though shooting in the Philippines was cheaper than shooting in the US, it brought with it its own set of problems: aside from torrential rain which halted production, at the time that the film was being made the Philippines was experiencing outbreaks of various diseases, and one of the film’s actresses, Lynn Borden, contracted typhoid whilst working on the picture (see Mask, 2009: 85).

Films about women in prison weren’t new at the time of the production of Black Mama, White Mama: pictures focusing on the incarceration of women had been made in Britain and America in the 1950s, including J Lee Thompson’s Yield to the Night (1956) and American films noir like John Cromwell’s Caged (1950) and Lewis Seiler’s Women’s Prison (1955). Often, these pictures were ‘worthy’ in their subject matter: for example, Yield to the Night engages with the issue of capital punishment through a narrative which alludes to the Ruth Ellis case. What was relatively new in terms of the WIP films of the 1970s was an increasing focus on nudity and explicit sexuality. This began with Jess Franco’s 99 Women (1969), a film which established many of the paradigms of WIP films of the 1970s, including an exotic locale (99 Women was set on an island prison), salacious nudity, and explicit scenes of lesbianism and rape. Films about women in prison weren’t new at the time of the production of Black Mama, White Mama: pictures focusing on the incarceration of women had been made in Britain and America in the 1950s, including J Lee Thompson’s Yield to the Night (1956) and American films noir like John Cromwell’s Caged (1950) and Lewis Seiler’s Women’s Prison (1955). Often, these pictures were ‘worthy’ in their subject matter: for example, Yield to the Night engages with the issue of capital punishment through a narrative which alludes to the Ruth Ellis case. What was relatively new in terms of the WIP films of the 1970s was an increasing focus on nudity and explicit sexuality. This began with Jess Franco’s 99 Women (1969), a film which established many of the paradigms of WIP films of the 1970s, including an exotic locale (99 Women was set on an island prison), salacious nudity, and explicit scenes of lesbianism and rape.

Franco would spend the 1970s and 1980s churning out a number of variations on the themes established in 99 Women, including films such as Des diamants pour l'enfer (Women Behind Bars, 1975), Frauengefängnis (Barbed Wire Dolls, 1976), Frauen für Zellenblock 9 (Women in Cellblock 9, 1978) and Sadomania (1981). Beginning with 99 Women, which was released in some territories in a XXX version that featured hardcore inserts, a good number WIP pictures of the 1970s were distributed in hardcore variants for territories in which that sort of thing was acceptable: this seemed a ‘natural’ evolution in a genre that was focused on the subjugation and torment of women for a predominantly male audience, and was also an outcome of the relaxation of laws and attitudes relating to sexually explicit material on film during the 1960s and 1970s. Those WIP pictures that didn’t make the leap into hardcore would usually feature extended shower scenes in which the bodies of the female cast were displayed for the pleasure of the viewer, and often for a voyeur within the film itself. These elements are present and correct in Black Mama, White Mama, which in its opening moments includes a sequence in which the female prisoners are forced to strip and shower, whilst the lesbian guard watches them Norman Bates-like through a spyhole and, as she does so, engages in a spot of self-love.

Roger Corman’s WIP films used Franco’s 99 Women as a model whilst also ‘incorporating the new social changes from the sixties—women’s liberation, the black civil rights movement, and the counterculture movement’ (Schubart, 2007: 45). The result was a brand of WIP film with two major characteristics: ‘Softcore sexual violence and a thin narrative of political revolution’ (ibid.). Given the exotic settings for many of these films, the appearance of Che Guevara-style guerillas was perhaps to be expected. Revolutionaries make an appearance in a number of Franco’s WIP pictures – it’s often a revolutionary group that stage a pivotal jailbreak in a WIP film. In Black Mama, White Mama, it is Ernesto’s group of guerillas that free Karen and Lee. However, the attempt to spring Karen from captivity is botched, and leads Karen and Lee to wander alone through the wilderness, chained together and initially disguised as nuns. Roger Corman’s WIP films used Franco’s 99 Women as a model whilst also ‘incorporating the new social changes from the sixties—women’s liberation, the black civil rights movement, and the counterculture movement’ (Schubart, 2007: 45). The result was a brand of WIP film with two major characteristics: ‘Softcore sexual violence and a thin narrative of political revolution’ (ibid.). Given the exotic settings for many of these films, the appearance of Che Guevara-style guerillas was perhaps to be expected. Revolutionaries make an appearance in a number of Franco’s WIP pictures – it’s often a revolutionary group that stage a pivotal jailbreak in a WIP film. In Black Mama, White Mama, it is Ernesto’s group of guerillas that free Karen and Lee. However, the attempt to spring Karen from captivity is botched, and leads Karen and Lee to wander alone through the wilderness, chained together and initially disguised as nuns.

The film features other paradigms of the WIP pictures of the era, including in its early sequences (those set in the prison camp) a juxtaposition of old lags who know the system with new prisoners. As the women shower together, one of the prisoners, an English woman named Ronda (Wendy Green), recognises another of the prisoners being shocked by the fact that they are expected to shower in cold water. ‘Ain’t you been in the can before, honey?’, Ronda asks, ‘It don’t warm up’. Another paradigm of the WIP film that is present and correct within Black Mama, White Mama is the sadistic punishment meted out to prisoners by the guards: when Lee and Karen fight in the canteen owing to Karen’s acceptance of Densmore’s offer of an easy ride in exchange for sexual favours, they are thrown into ‘the box’ by Densmore. ‘The box’ is a metal structure in a field, into which Karen and Lee are placed naked and strapped back-to-back; during the midday sun, the heat and lack of air circulation is unbearable, making ‘the box’ a pressure cooker and a metaphor, in a sense, of what the relationship between Karen and Lee will become once they escape from the prison chained together. The scene in ‘the box’ also offers the filmmakers a shot at another defining paradigm of the WIP film: nudity from the Markov and Grier. In fact, what’s striking about Black Mama, White Mama, in comparison with Grier’s later films for AIP, is the level of nudity.

In the chaining together of its black and white female leads for much of the film’s running time, Black Mama, White Mama makes obvious allusions to Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958), in which two members of a chain gang (Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier) escape but are shackled together and must overcome their mutual distrust in order to survive – eventually discovering that their dislike of one another evolves into respect. Here, in an inversion of her role in The Big Bird Cage (Jack Hill, 1972), in which she played a revolutionary, Grier plays the prostitute Lee Daniels, who has escaped from her pimp Vic with a sum of money stolen from Vic and the intention to flee the country; on the other hand, Lee’s white counterpart, Karen, is a bourgeois American woman who has fallen in love with the leader of a local group of guerilla fighters and is using her money to fund the guerillas’ activities. In the chaining together of its black and white female leads for much of the film’s running time, Black Mama, White Mama makes obvious allusions to Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958), in which two members of a chain gang (Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier) escape but are shackled together and must overcome their mutual distrust in order to survive – eventually discovering that their dislike of one another evolves into respect. Here, in an inversion of her role in The Big Bird Cage (Jack Hill, 1972), in which she played a revolutionary, Grier plays the prostitute Lee Daniels, who has escaped from her pimp Vic with a sum of money stolen from Vic and the intention to flee the country; on the other hand, Lee’s white counterpart, Karen, is a bourgeois American woman who has fallen in love with the leader of a local group of guerilla fighters and is using her money to fund the guerillas’ activities.

Chris Holmlund has also noted that in Black Mama, White Mama, as in Grier’s other prison films The Big Doll House (Jack Hill, 1971) and Women in Cages (Jerry de Leon, 1971), ‘Grier is paired with a white woman’ whereas in the urban ‘blaxploitation’ films (Foxy Brown, Coffy, ‘Sheba, Baby!’) ‘whites are never her partners, let alone […] her lovers: those privileges are preserved for black men’ (Holmlund, 2008: 66). Holmlund quotes Mayne’s observation that in Grier’s prison films ‘discourses of race and discourses of lesbianism’ not only ‘coexist’ but are predicated on ‘profound connections between them. The lesbian plot requires the racial plot, and the racial plot requires the lesbian plot’ (Mayne, quoted in ibid.). However, significantly in Black Mama, White Mama, the relationship between Karen and Lee is neither romantic nor sexual: they develop a mutual respect for one another, but within the film lesbianism is associated with patriarchy; with the guards at the prison camp who exploit the mostly young women who are placed in their charge.

Logan and Densmore’s relationship, together with their treatment of the prisoners, is a metonym for the prison camp’s corruption as a symbol of ‘rehabilitation’. Logan and Densmore, we are led to believe, are involved as lovers. However, Densmore spies on the female inmates as they shower, masturbating as she does so – with the knowledge of Logan. ‘Enjoy it?’, Logan asks Densmore when she spots her leavint the area in which the spyhole to the communal shower is found. ‘Jealous?’, Densmore teases Logan. ‘Keep it up and you’ll go blind’, Logan quips back. Densmore also ‘uses’ the new prisoners for her own sexual gratification, in exchange for relaxed penalties or other ‘favours’. Early in the film, Ronda shares a joint with her fellow prisoners and tells Karen and Lee ‘I like to make things comfortable. If you know the right people in here, you can get anything you want’. Logan and Densmore’s relationship, together with their treatment of the prisoners, is a metonym for the prison camp’s corruption as a symbol of ‘rehabilitation’. Logan and Densmore, we are led to believe, are involved as lovers. However, Densmore spies on the female inmates as they shower, masturbating as she does so – with the knowledge of Logan. ‘Enjoy it?’, Logan asks Densmore when she spots her leavint the area in which the spyhole to the communal shower is found. ‘Jealous?’, Densmore teases Logan. ‘Keep it up and you’ll go blind’, Logan quips back. Densmore also ‘uses’ the new prisoners for her own sexual gratification, in exchange for relaxed penalties or other ‘favours’. Early in the film, Ronda shares a joint with her fellow prisoners and tells Karen and Lee ‘I like to make things comfortable. If you know the right people in here, you can get anything you want’.

Sex seems to be the only currency worth anything within the prison and, for that matter, outside of it (‘How about the minister?’, Cruz asks Galindo pointedly after speaking with a prostitute who identifies Galindo as a frequent client, ‘Does he know her too?’). Inside the prison, Karen asks if someone might be able to get hold of a gun in the camp, and Ronda tells her ‘To get a gun, you need something to trade that’s pretty damn valuable. What you got, besides your ass?’ Karen asks Ronda about Densmore: ‘What’s her scene?’ ‘She’s got this thing going with Logan’, Ronda replies, ‘But she likes a lot of side action. If she digs you, things in here can be a hell of a lot easier’. Soon, Lee is called into Densmore’s office, and having taken an interest in Lee, Densmore attempts to seduce Lee and ply her with alcohol. Lee refuses to play ball. ‘What’s the matter? Don’t you indulge?’, Densmore asks her. ‘When I feel like it’, Lee replies. The conversation is ostensibly about alcohol but the two actresses’ delivery suggests that Densmore and Lee are also referring to lesbian sex, Lee’s refusal of Densmore’s drink also a refusal of Densmore’s attempt to get her into bed. However, Karen is more amenable to Densmore’s demands: the next day, whilst the inmates are working in the fields, Densmore calls Karen out – presumably to make the same proposition to her that she made to Lee. At lunch, Lee confronts Karen, chastising her and reminding her that the other inmates had to take on extra work in order to cover Karen’s absence (whilst she was presumably fucking Densmore). ‘You had your chance and blew it’, Karen tells Lee, leading them to fight one another in the canteen.

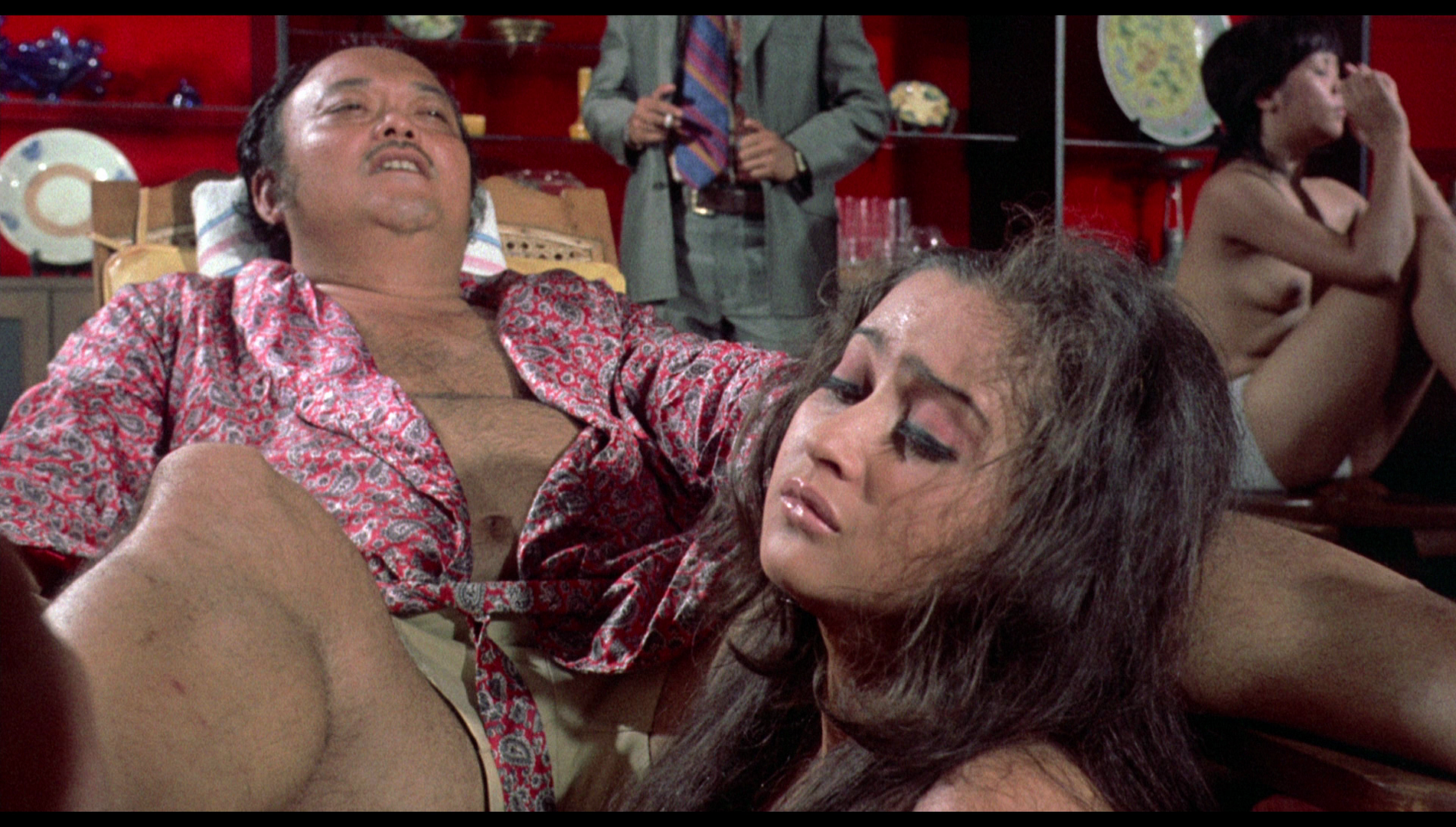

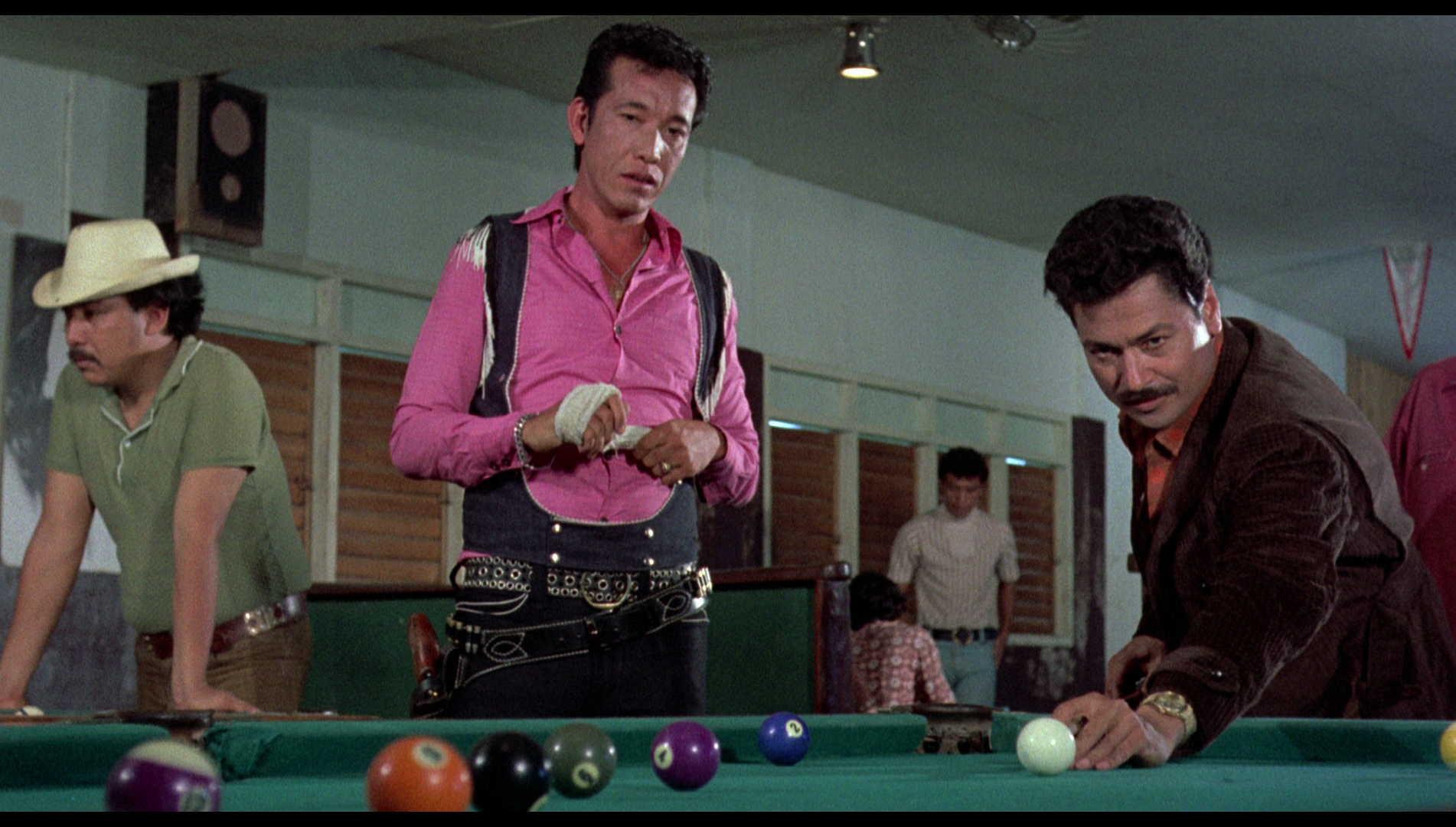

Outside the prison camp, the two women are sought by four groups, each headed by a different male figure of authority (Ernesto, Vic, Ruben and Captain Cruz/Galindo) and with different designs on Karen and Lee. Ernesto needs to reconnect with Karen, because the guerillas need her money and connections to buy their small arms. Captain Cruz, motivated by local politico Galindo, needs to recapture both women so that they may be returned to the prison camp – Galindo, in particular, wants to ensure that Karen doesn’t fall into the hands of the guerillas, which would result in her enabling their revolutionary activities to expand. Cruz enlists Ruben to assist in tracking the two women, as Ruben knows the terrain and has connections that Cruz does not. Cruz offers Ruben $10,000 to find and return the women; Ruben is unaware of Cruz’s motivations but agrees to help. (‘What kind of women are worth that much?’, Ruben asks. ‘These two are’, Cruz tells him.) However, Ruben needs Cruz to stay out of his way: ‘A reputation for helping cops is shit for my image, so you keep your ass out of my province’, Ruben tells Cruz. Vic, perhaps, is the film’s true antagonist, and is motivated solely by his desire to ‘punish’ Lee (‘The black bitch. Find her’, he commands) and get his hands on the $40,000 she stole from him. An ugly character with a lazy demeanour (somewhat reminiscent of Mr Big in Ian Fleming’s novel Live and Let Die, 1954), Vic is introduced torturing a topless girl, Juana (Alone Alegre) with electricity (‘No-one betrays me, Juana’, he asserts, ‘No-one runs away… ever’). A pimp and drug dealer, Vic boasts that ‘I sell more junk than anybody on the islands, and I have more whores humping in my houses. Should one bitch matter to me?’ Outside the prison camp, the two women are sought by four groups, each headed by a different male figure of authority (Ernesto, Vic, Ruben and Captain Cruz/Galindo) and with different designs on Karen and Lee. Ernesto needs to reconnect with Karen, because the guerillas need her money and connections to buy their small arms. Captain Cruz, motivated by local politico Galindo, needs to recapture both women so that they may be returned to the prison camp – Galindo, in particular, wants to ensure that Karen doesn’t fall into the hands of the guerillas, which would result in her enabling their revolutionary activities to expand. Cruz enlists Ruben to assist in tracking the two women, as Ruben knows the terrain and has connections that Cruz does not. Cruz offers Ruben $10,000 to find and return the women; Ruben is unaware of Cruz’s motivations but agrees to help. (‘What kind of women are worth that much?’, Ruben asks. ‘These two are’, Cruz tells him.) However, Ruben needs Cruz to stay out of his way: ‘A reputation for helping cops is shit for my image, so you keep your ass out of my province’, Ruben tells Cruz. Vic, perhaps, is the film’s true antagonist, and is motivated solely by his desire to ‘punish’ Lee (‘The black bitch. Find her’, he commands) and get his hands on the $40,000 she stole from him. An ugly character with a lazy demeanour (somewhat reminiscent of Mr Big in Ian Fleming’s novel Live and Let Die, 1954), Vic is introduced torturing a topless girl, Juana (Alone Alegre) with electricity (‘No-one betrays me, Juana’, he asserts, ‘No-one runs away… ever’). A pimp and drug dealer, Vic boasts that ‘I sell more junk than anybody on the islands, and I have more whores humping in my houses. Should one bitch matter to me?’

As members of the criminal underground, Ruben and Vic are in competition with one another. Ruben, dressed conspicuously as a cowboy and driving a jeep decorated with buffalo horns, seems to represent the exploitation of the local community by outsiders. Played with Sid Haig’s usual mixture of easy, laid-back Californian charm and moments of menace, Ruben’s relaxed demeanour is contrasted with the severity of Vic’s desire for revenge. (‘That greasy cowboy’, Vic asserts in reference to Ruben, ‘He doesn’t have the balls to pressure us’.) Vic is an angry, spiteful character – though he is lazy, often shown reclining in an armchair whilst enlisting others to do his dirty work for him. Vic surrounds himself with topless women, their presence seemingly giving him no pleasure; whereas Ruben stops off at a local business associates’ house for information and engages in a threesome with the man’s two daughters, the three of them laughing and joking as they make love.

Each of these male groups is attempting to catch Karen and Lee for different reasons, but regardless of this there is a sexual motive for each of these men: Ernesto is motivated by his desire for Karen, which is also connected with his need to use her money and influence to arm his guerilla group. Mirroring Karen’s relationship with Ernesto, which is built on sex but has a subtext of exploitation, the dialogue suggests that Vic has been involved in a sexual relationship with Lee in the past: Lee used her sexuality to get close to Vic, thus enabling her to win his trust and steal his money. Vic is painted as a sexual sadist, from his introductory scene in which he is torturing the topless Juana with electricity. Galindo, the film suggests, frequents some of the prostitutes in Vic’s ‘stable’; this is something that attracts the scorn of Captain Cruz. Meanwhile, Ruben temporarily abandons his search for Karen and Lee in order to engage in the aforementioned threesome with two sisters. Angered by Cruz and Galindo’s exploitation of him, Ruben humiliates these two representatives of ‘legitimate’ authority sexually: when Cruz and Galindo stray onto his turf, Ruben asks one of the prostitutes which of the pair ‘has got the biggest pecker’ before forcing them to lower their trousers in order to investigate for himself. Naturally, these groups of men come into conflict with one another, Ruben and his gang standing off against Ernesto’s guerillas in a scene that is shot like duel in one of Sergio Leone’s westerns all’italiana: all long shots intercut with close-ups and over-the-shoulder shots. Each of these male groups is attempting to catch Karen and Lee for different reasons, but regardless of this there is a sexual motive for each of these men: Ernesto is motivated by his desire for Karen, which is also connected with his need to use her money and influence to arm his guerilla group. Mirroring Karen’s relationship with Ernesto, which is built on sex but has a subtext of exploitation, the dialogue suggests that Vic has been involved in a sexual relationship with Lee in the past: Lee used her sexuality to get close to Vic, thus enabling her to win his trust and steal his money. Vic is painted as a sexual sadist, from his introductory scene in which he is torturing the topless Juana with electricity. Galindo, the film suggests, frequents some of the prostitutes in Vic’s ‘stable’; this is something that attracts the scorn of Captain Cruz. Meanwhile, Ruben temporarily abandons his search for Karen and Lee in order to engage in the aforementioned threesome with two sisters. Angered by Cruz and Galindo’s exploitation of him, Ruben humiliates these two representatives of ‘legitimate’ authority sexually: when Cruz and Galindo stray onto his turf, Ruben asks one of the prostitutes which of the pair ‘has got the biggest pecker’ before forcing them to lower their trousers in order to investigate for himself. Naturally, these groups of men come into conflict with one another, Ruben and his gang standing off against Ernesto’s guerillas in a scene that is shot like duel in one of Sergio Leone’s westerns all’italiana: all long shots intercut with close-ups and over-the-shoulder shots.

Judith Mayne has suggested that ‘the difference between a “political prisoner” and a prostitute is one of the defining characteristics of the 1970s version of this genre [the prison film]’ (Mayne, 2000: 134). It’s this relationship that Black Mama, White Mama explores (and is reflected in the film’s title itself), suggesting that both women – Karen the revolutionary; and Lee, the prostitute – are united in their struggle against patriarchy. Entering into the camp, Karen and Lee are reminded that it is a place where contentious ideas are not permitted: one of the guards tells Karen that ‘There’s no room for revolution in here. Remember that’. At one point in the film Lee makes the association between Karen’s struggle against the status quo and Lee’s own repression by her role as a prostitute explicit when she tells Karen ‘I’ve been a revolutionary since I was thirteen, when I was first paid to “do it”’. Meanwhile, slightly earlier in the film, Karen uses a similar argument as part of a plea for Lee to co-operate with her, but Karen’s rhetoric ends up sounding deeply patronising: ‘We’re trying to set this island free’, Karen asserts before adding, ‘Christ, you’re black. You understand, don’t you?’

Mayne suggests that the pairing of Karen and Lee has a ‘racist implication’ too, in the sense that ‘the black woman [Lee] is put in the stereotypical position of “body”, while the white woman [Karen] is defined by her “mind” […] [and] political affiliations’ (ibid.). The dialogue between the two is sometimes didactic in this regard. For example, after Karen and Lee have been thrown in ‘the box’ owing to their fight over Karen’s acceptance of Densmore’s proposition, Lee tells Karen that she simply doesn’t ‘like holding up somebody else’s end. Everybody shares everything. You’re the revolutionary. You should be able to dig on that’. Karen responds by asserting she is simply ‘looking for a way out of this camp. I’ll do anything I have to’. ‘That’s cool’, Lee declares, ‘Just don’t put any extra weight on me’. Although both motivated by the desire to reclaim their freedom, and eventually they overcome their differences and form a sense of mutual respect for one another, Karen and Lee have different goals and very different backgrounds. ‘I’ve spent the last two years living with a prick I hate [Vic], so I could beat him out of enough cash to get me what I’ve been after all my life [….] and some jive-ass revolution don’t mean shit to me’, Lee tells Karen. In response to this, Karen declares that ‘I’ve had money all my life’. ‘Oh, my heart bleeds for you’, Lee asserts sarcastically. ‘It didn’t get me anything, ever’, Karen continues. ‘Is this two-bit hick island that important to you?’, Lee asks in response before suggesting that Karen’s involvement with the revolutionaries may have been born as much out of a bourgeois sense of ennui as by a genuine sympathy for their cause: ‘If it is, maybe your good life back home got old and this is the little rich chick’s new toy’. Mayne suggests that the pairing of Karen and Lee has a ‘racist implication’ too, in the sense that ‘the black woman [Lee] is put in the stereotypical position of “body”, while the white woman [Karen] is defined by her “mind” […] [and] political affiliations’ (ibid.). The dialogue between the two is sometimes didactic in this regard. For example, after Karen and Lee have been thrown in ‘the box’ owing to their fight over Karen’s acceptance of Densmore’s proposition, Lee tells Karen that she simply doesn’t ‘like holding up somebody else’s end. Everybody shares everything. You’re the revolutionary. You should be able to dig on that’. Karen responds by asserting she is simply ‘looking for a way out of this camp. I’ll do anything I have to’. ‘That’s cool’, Lee declares, ‘Just don’t put any extra weight on me’. Although both motivated by the desire to reclaim their freedom, and eventually they overcome their differences and form a sense of mutual respect for one another, Karen and Lee have different goals and very different backgrounds. ‘I’ve spent the last two years living with a prick I hate [Vic], so I could beat him out of enough cash to get me what I’ve been after all my life [….] and some jive-ass revolution don’t mean shit to me’, Lee tells Karen. In response to this, Karen declares that ‘I’ve had money all my life’. ‘Oh, my heart bleeds for you’, Lee asserts sarcastically. ‘It didn’t get me anything, ever’, Karen continues. ‘Is this two-bit hick island that important to you?’, Lee asks in response before suggesting that Karen’s involvement with the revolutionaries may have been born as much out of a bourgeois sense of ennui as by a genuine sympathy for their cause: ‘If it is, maybe your good life back home got old and this is the little rich chick’s new toy’.

Video

Taking up just under 24Gb of space on the disc, Black Mama, White Mama is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film itself is very ‘flatly’ photographed, which is consistent with the quick, cheap nature of the production itself. Focal lengths used in the photography seem to be within the standard/short telephoto range (35mm/50mm, most likely); compositions sometimes seem a little uncomfortable, which again may be seen as a characteristic of a rushed production. The presentation, however, is very good. In a notable improvement over the previously available DVDs, this Blu-ray presentation displays beautiful colour consistency: for example, in the opening sequence, the vivid red of Grier’s dress is contrasted sharply with the greens and browns of the terrain. An excellent level of detail is present throughout, and the source for the material is free from any distracting damage. Contrast levels are good, balanced and consistent, with mid-tones being strong in definition and both highlights and shadows feeling ‘protected’. Finally, the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film – though there are a few very brief spots where this feels a little ‘clumpy’ and inorganic. These are fleeting, however. Taking up just under 24Gb of space on the disc, Black Mama, White Mama is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film itself is very ‘flatly’ photographed, which is consistent with the quick, cheap nature of the production itself. Focal lengths used in the photography seem to be within the standard/short telephoto range (35mm/50mm, most likely); compositions sometimes seem a little uncomfortable, which again may be seen as a characteristic of a rushed production. The presentation, however, is very good. In a notable improvement over the previously available DVDs, this Blu-ray presentation displays beautiful colour consistency: for example, in the opening sequence, the vivid red of Grier’s dress is contrasted sharply with the greens and browns of the terrain. An excellent level of detail is present throughout, and the source for the material is free from any distracting damage. Contrast levels are good, balanced and consistent, with mid-tones being strong in definition and both highlights and shadows feeling ‘protected’. Finally, the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film – though there are a few very brief spots where this feels a little ‘clumpy’ and inorganic. These are fleeting, however.

This presentation of the film is uncut, running for 86:38 mins. (The BBFC-imposed cuts that affected some of the film’s previous home video releases have been waived.)

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is clear and demonstrates good enough range – though it’s not a ‘showy’ sound mix, by any stretch of the imagination. The optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes:

- an audio commentary with film historian Andrew Leavold. Leavold situates Black Mama, White Mama within a tradition during the period of its production of US filmmakers shooting pictures in the Philippines. Leavold highlights the ways in which the film conforms to the template of the previous WIP pictures that featured Grier, and he also discusses some of the locations used in the picture. He reflects on the cast and crew, discussing the other films of Eddie Romero. - an audio commentary with film historian Andrew Leavold. Leavold situates Black Mama, White Mama within a tradition during the period of its production of US filmmakers shooting pictures in the Philippines. Leavold highlights the ways in which the film conforms to the template of the previous WIP pictures that featured Grier, and he also discusses some of the locations used in the picture. He reflects on the cast and crew, discussing the other films of Eddie Romero.

- ‘White Mama Unchained’ (14:01). In this interview, recorded in 2015, Margaret Markov talks about how she came to be an actress in films and reflects on her early screen roles. She reflects on the techniques of some of the directors with whom she worked. Markov discusses some of the dangers involved in shooting Black Mama, White Mama in the Philippines, revealing that she suffered from heat stroke during the production and was also bitten by a spider. She talks at length about working with some of the other actors, including of course Grier, but also Vic Diaz and Sid Haig. Markov also discusses her work on The Arena with Grier.

- ’Sid Haig’s Filipino Adventures’ (15:51). Here, in an interview shot in 2015, Haig discusses his experiences of making films in the Philippines during the early 1970s – not just Black Mama, White Mama, but also The Big Bird Cage and The Big Doll House. Haig talks about working with Grier and offers numerous fascinating anecdotes about the production of these films.

- ‘The Mad Director of Blood Island’ (14:38). In an archival interview, Eddie Romero discusses his work as a film director.

- Trailer (1:54).

- Gallery (0:25).

Retail copies also include reversible sleeve artwork.

Overall

Black Mama, White Mama is an entertaining film, the last of its kind before Grier transitioned to starring roles in urban ‘blaxploitation’ films – a cycle that began with Coffy. Black Mama, White Mama has all the characteristics one would expect from a WIP picture of this vintage. Its reworking of The Defiant Ones arguably works because of the two lead actresses, and the picture is also filled with some very good supporting performances (from Haig and Diaz, in particular). Black Mama, White Mama is an entertaining film, the last of its kind before Grier transitioned to starring roles in urban ‘blaxploitation’ films – a cycle that began with Coffy. Black Mama, White Mama has all the characteristics one would expect from a WIP picture of this vintage. Its reworking of The Defiant Ones arguably works because of the two lead actresses, and the picture is also filled with some very good supporting performances (from Haig and Diaz, in particular).

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation is very good indeed, an easy upgrade over the film’s previous home video releases. The main feature is accompanied by some impressive contextual material in the form of interviews with Markov, Haig and Romero. It’s a pleasing package that helps to round out Arrow’s highly welcome run of HD releases of Pam Grier’s AIP pictures.

References:

Holmlund, Chris, 2008: ‘Wham! Bam! Pam!: Pam Grier as Hot Action Babe and Cool Action Mama’. In: Gabbard, Krin & Luhr, William (eds), 2008: Screening Genders. Rutgers University Press: 61-77

Mask, Mia, 2009: Divas on Screen: Black Women in American Film. University of Illinois Press

Mayne, Judith, 2000: Framed: Lesbians, Feminists, and Media Culture. University of Minnesota Press

Schubart, Rikke, 2007: Super Bitches and Action Babes: The Female Hero in Popular Cinema, 1970-2006. London: McFarland and Company

|