|

|

Horse Money

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Second Run Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (10th April 2016). |

|

The Film

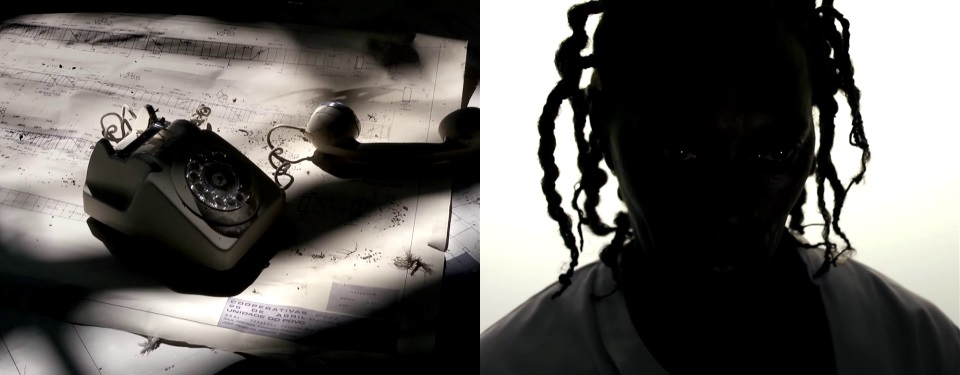

Traveling to Cape Verde with the intention of remaking Jacques Tourneur's I Walked with a Zombie on a low budget, director Pedro Costa (O Sangue) found himself as entranced by the place and the people as his heroine (Gang of Four's Inês de Medeiros). Alienating most of the film's crew – and co-star Isaach De Bankolé (White Material) whose role as the "zombie" was further diminished – Costa spirited away the camera, sound engineer, and stars Medeiros, Edith Scob (Summer Hours), & Pedro Hestnes (August) to create a filmic portrait of the Cape Verdians and their haunted landscape. The resulting film Casa de Lava inadvertently provided what would be the focus of his subsequent films when the locals gave him letters and gifts to take back to the Cape Verdian population of the Fontainhas slum outside Lisbon. His first attempt to tell a fictional story in Fontainhas was Ossos, which he later judged as a failure, finding the machinery of traditional filmmaking detrimental to the intimacy he sought; but he did make the acquaintance of Vanda Duarte who would become the subject of his next film In Vanda's Room which he would shoot and edit himself over the next two years, during which time Fontainhas was torn down and the residents moved to low-rent apartment high-rises. Costa had also made the acquaintance of Ventura, venerable sentinel of Fontainhas' night activities, documenting his family's move into the apartment the man quickly came to despise. His visits to other former residents of Fontainhas who he regarded as his "children" – interweaving aspects of his own past with theirs – became the subject of Costa's acclaimed Colossal Youth. Eight years later, Horse Money finds Ventura looking back on his own past in a sinister hospital in which he is undergoing "treatment" for an undisclosed ailment (possibly psychological since he explains the twitching of his right hand as an effect of the medications) in a sort of variation on Wojciech Has' The Hourglass Sanatorium stripped of its baroque embellishments. Passing through a sort of landscape of the mind made up of dark hospital corridors and stone catacombs, Ventura relives and recites not so much past episodes but anecdotes thematically linked to fears (sometimes expressed as anxiety over losing his work contract) and failures (although he pines for wife Clothilde in Colossal Youth who abandoned him, here he references his desire to raise enough money to bring his wife Zulmira from Cape Verde but we never learn if he succeeded) after arriving in Portugal in the seventies during the Carnation Revolution which has been regarded as a "peaceful military coup" since no shots were fired. When he lies in his hospital bed, he is visited by ghosts including Delgado who has not spoken since he set his home on fire with his sleeping family inside it, nephew Benvindo who suffers from seizures after falling from the third floor of a construction site (not unlike Leão in Casa de Lava, and Lento who got hooked on the drugs he was selling to supplement his pay as laborer, among others ("We've always lived and died this way"). Ventura's sense of loss is deepened he meets Vitalina (Vitalina Varela) who has just arrived in Cape Verde to bury her husband. When he asks of his old home, she tells him "not a stone left standing." When he asks of his donkey, she tells him that it is dead. When he asks of his horse Dinheiro, she tells him "The vultures tore him to pieces." Her story of her feverish journey from Cape Verde to Lisbon is contrasted with her reading of the official record of her birth, marriage, and the death of her husband; the former establishing her as a kindred spirit to the émigrés and the latter offered up as the sort of bureaucratic summing-up that Ventura refused to submit to here when questioned by an off-screen doctor in the examination room and in Colossal Youth as a social worker tried to solicit information about the size of his family to determine a suitable dwelling for him. Although a real person whose biography has been incorporated into her character, we wonder if she too may be a ghost of Ventura's past since she is younger but knows of his past existence in Cape Verde. As the corridors take him from hospital rooms and offices to the ruins of places he has worked, he finds it more difficult to connect with the ghosts (perhaps symbolized by his attempts to get a connection out of dead rotary phones and the argument with his nephew that breaks out over the correct lyrics of a song). Having seemingly completed his therapy – critic Chris Fujiwara in the Second Run Blu-ray's accompanying booklet likens it to a kind of "talking cure" – Ventura finds he still has some ghosts to exorcise. In a twenty-minute sequence that comprised in a different edit the entirety of Costa's short Sweet Exorcism that formed part of the anthology Centro Histórico – along with works by Abraham's Valley's Manoel de Oliveira, Spirit of the Beehive's Victor Erice, and Le Havre's Aki Kaurismäki – Ventura finds himself trapped in a stalled elevator with the statue of a Carnation Revolutionary Army soldier. Even more suggestive that many or all of Ventura's encounters in the film are projections of the mind ("You think I like being trapped with you for thirty-eight years"), Ventura and the soldier (whose position changes via cutaways and is only once seen moving) discuss his run-in with soldiers in which he was dragged into the woods, beaten, stripped of his knife and wedding ring, and left for dead; the encounter symbolizing an earlier attempt to erase the presence of the disenfranchised from history (in an interview, Costa describes how he and Ventura experienced the revolution differently, citing the presence of only white faces in photographic coverage of the crowds on Freedom Day). While I certainly found the film mesmerizing on first and second view - while still no more sure than others about whether I have reconciled the plot elements in a meaningful manner - time will tell if remains as arresting as Costa's earlier Colossal Youth.

Video

Second Run's first Blu-ray - now distributed by Arrow Films - is a knockout giving this 1080i50 (original framerate) pillarboxed MPEG-4 AVC 1.33:1 production a strong encode with deep blacks that often erase the framelines while encouraging the viewer to peer deep into the compositions. Costa claims that the film was shot with a Panasonic AG-DVX100 camcorder capturing the image to P2 cards, although that model number is listed online as an SD camera and this is certainly does not look like a production upscaled in post or to Blu-ray from an SD master (presumably it was shot on Panasonic's successor model the HVX200 which was the first to utilize the capture to solid state memory).

Audio

Audio options include the original Portuguese/Kabuverdianu 5.1 mix in DTS-HD Master Audio and a serviceable 2.0 stereo downmix in LPCM. This is not a constantly active surround sound system demo disc. Much of the dialogue-heavy film is front-oriented but the clanking of elevator doors, footsteps down corridors, the banging and breaking of push-button telephones, and blasts of organ music give a sense of depth that is the aural equivalent to depth of the wide-angle compositions.

Extras

Extras start off with the 2010 short film O Nosso Homem (25:15) - available online at the moment on Vimeo - not so much a follow-up to Colossal Youth but more similar in tone and theme to it than Costa's earlier Fontainhas films. Less interesting is an introduction to the film by filmmaker Thom Andersen (5:09) in which he highlights the use of photographs by Jacob Riis of New York's immigrant population in the earlier half of the last century, the somewhat rambling nature of it forgivable when one takes into account that it is not an audio essay but a recording of a screening introduction placed on top of the images. More interesting and engaging is Pedro Costa in conversation with Laura Mulvey (40:53), also shot late last year for the UK premiere, in which the director discusses the trajectory from Casa de Lava to the Fontainhas trilogy (as well as the shorts), the whereabouts of Vanda, his introduction to Ventura, the differences between Sweet Exorcism and the version in Horse Money, and how his and Ventura's differing experiences of the Carnation Revolution shaped the feature. Also included are the UK trailer (1:43), the international trailer (3:31), and four teasers (0:30 + 0:19 + 0:29 + 0:18).  The included booklet (sized for the Blu-ray package but the same one in content and dimension for the DVD edition) features two essays on the film by Jonathan Romney and Chris Fujiwara in which the former describes the film as a "journey to the end of night" while the latter contrasts the "poetry" of bureaucratic language with the protagonists' attitude towards language. Cinema Guild has announced the film for Blu-ray release in the US later this year - presumably in a 1080p24 conversion like most domestic releases of 1080i50 films - with O Nosso Homem and Fujiwara's essay currently listed as the only extras.

Overall

While I certainly found the film mesmerizing on first and second view - while still no more sure than others about whether I have reconciled the plot elements in a meaningful manner - time will tell if remains as arresting as Costa's earlier Colossal Youth.

|

|||||

|