|

|

Kill! AKA Burai barase! AKA Outlaw: Rub-out! (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th May 2016). |

|

The Film

Outlaw Gangster VIP Collection Outlaw Gangster VIP Collection

In 1956, Japanese filmmaking studio Nikkatsu began to produce their youth-oriented mukokuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures. The first of these films was Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun (1956). Beginning with Furukawa’s picture, the films were considered ‘borderless’ in the sense that they drew from American and European cinema, taking something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixing it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. One of the closest corollaries to Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless action’ films is perhaps the work of Jean-Pierre Melville, the French filmmaker who with films such as Le samourai (1967) and Le cercle rouge (1970) married the independence and auteurist experimentation of the French nouvelle vague with the iconography (and narrative conventions) of the Hollywood gangster film. Although Japanese cinema had made films focusing on yakuza prior to Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon pictures, the mukokuseki akushon films differed from their predecessors by abandoning a period setting, placing their narratives in the present day, and by drawing from the iconography of both American and European films. Jasper Sharp has reminded us that though the mukokuseki akushon films featured a contemporary setting, they ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ and their depiction of Japanese society is highly stylised (Sharp, 2011: 182). 1967 marked something of a turning point in terms of Japanese yakuza pictures: that was the year in which Suzuki Seijun made his anarchic and subversive Branded to Kill (1967), a film which turned the paradigms of the genre on their head, much to the chagrin of Nikkatsu itself. The most striking yakuza pictures of that year, Branded to Kill and Nomura Takashi’s A Colt is My Passport, were shot in stark monochrome. In the years that followed, the audience for the mukokuseki akushon pictures dwindled, and in the 1970s Nikkatsu turned away from the youth comedies and gangster films that had been its forte since the mid-1950s, focusing instead on the production of Roman Porno films – erotic pictures that subsequently came to define the Nikkatsu ‘brand’ for many years to come.  Produced at the tail-end of the popularity of the mukokuseki akushon pictures and with the first film in the series (Masuda Toshio’s Gangster VIP, 1968) being released a year after Branded to Kill and A Colt is My Passport, the Outlaw Gangster (Burai/’Hoodlum’) films show the changes in this subgenre; as the series progresses, the films feature an increasing emphasis on sex and sadistic spectacle. (The final film in the series features in its first five minutes a vicious knife fight which climaxes with one character having their eye gouged out in brutal close-up.) In retrospect, the films seem transitional, foreshadowing Nikkatsu’s progression into the production of Roman Porno films that would take place in the 1970s and the emphasis on ‘true’ stories of murder and bloodshed that would characterise the nihilistic, documentary-style Jitsuroku films of the 1970s (for example, Fukasaku Kinji’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity, 1973). As Mark Schilling has noted, Gangster VIP is in ‘tone and style’ very similar to Fukasaku’s 1971 Street Mobster, which was one of the earliest Jitsuroku films (Schilling, 2007: 56). Many of the later Jitsuroku films would attempt to establish their verisimilitude through, besides the documentary style of their shooting, basing their narratives on the memoirs of real members of the yakuza community, and like Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor (1975) the Outlaw Gangster series is based on the memoirs of yakuza Fujita Goro. Furthermore, as if to consolidate the movement away from the film noir aesthetic of Branded to Kill and A Colt is My Passport, like the later Jitsuroku films Gangster VIP and its sequels were shot in colour too. Produced at the tail-end of the popularity of the mukokuseki akushon pictures and with the first film in the series (Masuda Toshio’s Gangster VIP, 1968) being released a year after Branded to Kill and A Colt is My Passport, the Outlaw Gangster (Burai/’Hoodlum’) films show the changes in this subgenre; as the series progresses, the films feature an increasing emphasis on sex and sadistic spectacle. (The final film in the series features in its first five minutes a vicious knife fight which climaxes with one character having their eye gouged out in brutal close-up.) In retrospect, the films seem transitional, foreshadowing Nikkatsu’s progression into the production of Roman Porno films that would take place in the 1970s and the emphasis on ‘true’ stories of murder and bloodshed that would characterise the nihilistic, documentary-style Jitsuroku films of the 1970s (for example, Fukasaku Kinji’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity, 1973). As Mark Schilling has noted, Gangster VIP is in ‘tone and style’ very similar to Fukasaku’s 1971 Street Mobster, which was one of the earliest Jitsuroku films (Schilling, 2007: 56). Many of the later Jitsuroku films would attempt to establish their verisimilitude through, besides the documentary style of their shooting, basing their narratives on the memoirs of real members of the yakuza community, and like Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor (1975) the Outlaw Gangster series is based on the memoirs of yakuza Fujita Goro. Furthermore, as if to consolidate the movement away from the film noir aesthetic of Branded to Kill and A Colt is My Passport, like the later Jitsuroku films Gangster VIP and its sequels were shot in colour too.

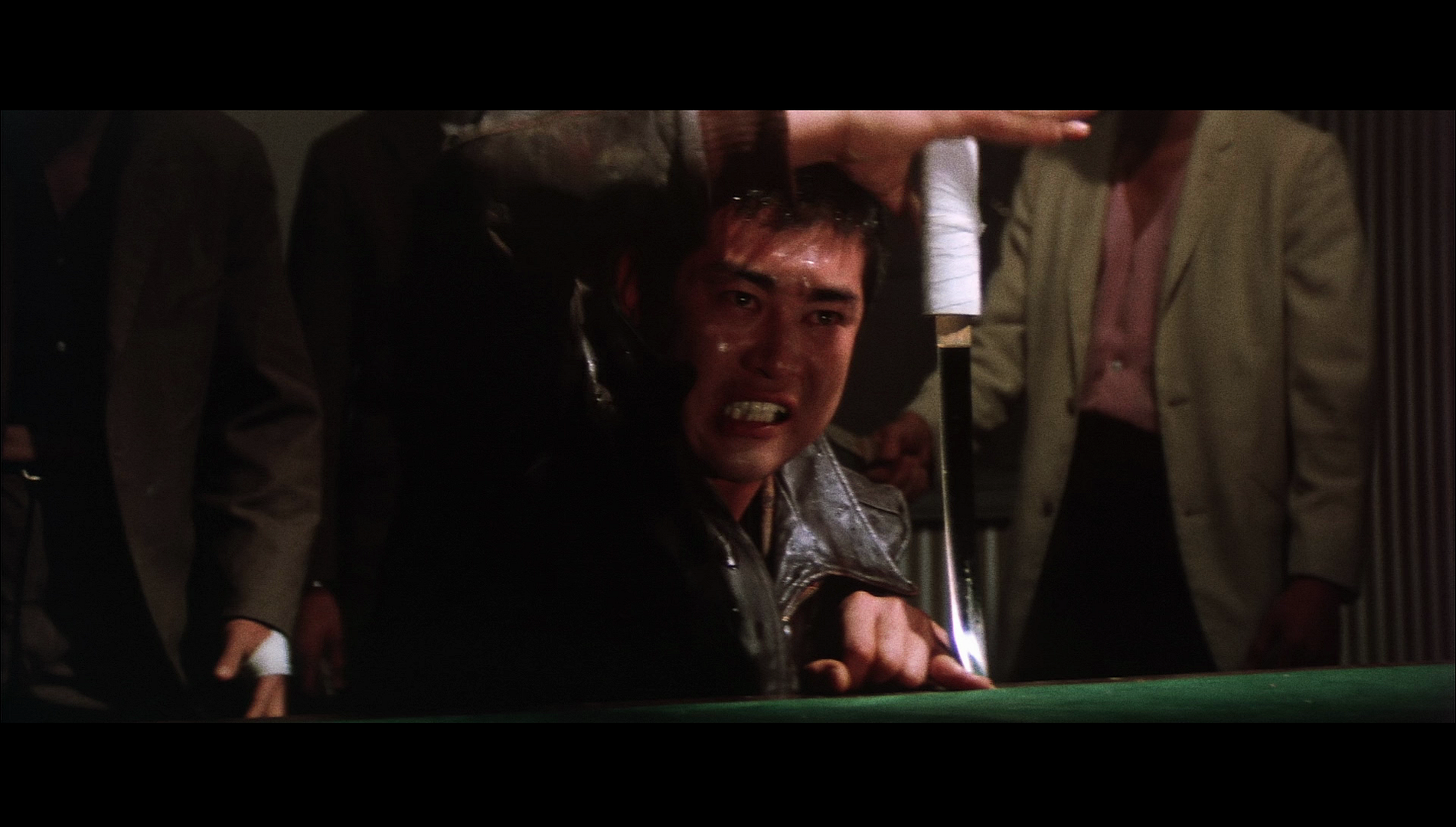

Each of the films stars Watari Tetsuya. The director of Gangster VIP (the first film in the Outlaw Gangster series, released in 1968), Masuda Toshio, had previously directed Watari in Velvet Hustler (also released in the US as Like a Shooting Star, 1967), Masuda’s remake of his own Red Quay (1958, previously released on Blu-ray by Arrow as part of their Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol. 1 set; read our review of that release here). In both The Velvet Hustler and Gangster VIP, Watari plays a yakuza named Goro, though as noted above Gangster VIP’s Goro is based on real life yakuza Fujita Goro.  Masuda had made his mark as a director for Nikkatsu with his third feature, the 1958 picture Rusty Knife. Masuda’s career with Nikkatsu roughly spans the years of the mukokuseki akushon cycle, beginning not long after the creation of this subtype of films and ending just prior to Nikkatsu’s movement into producing Roman Porno pictures. Like a number of the mukokuseki akushon films, the Outlaw Gangster pictures take some of their narrative cues from Westerns – and particularly, the westerns all’italiana of the period. Masuda once referred to Gangster VIP as ‘a youth film that happens to be set in the yakuza world’ (Masuda, quoted in Schilling, 2007: 56). That approach is certainly evident within the film itself. Like a number of the anti-heroes of the mukokuseki akushon films, Goro is a rebellious figure; dressed in a leather jacket and accompanied by moody songs on the soundtrack, Goro is reminiscent of the characters played by James Dean and Elvis Presley in the American youth pictures of the 1950s. Where earlier period-set yakuza films (jidaigeki) had traditionally featured Westernised villains, the mukokuseki akushon pictures had anti-heroes who were often Westernised, and who went against the strict codes of conduct of the yakuza. (This Westernised depiction of the heroes of these films is also embodied in the Gangster VIP films, and in many other examples of the genre, by the seemingly ubiquitous nightclub sequences, which feature bizarrely Americanised nightclubs populated by sultry lounge singers and whisky-drinking gangsters.) In this way, the films foregrounded themes of inter-generational conflict – much like the American youth pictures of the 1950s and 1960s. The mukokuseki akushon films could oscillate between outlandish and camp (for example, Hasebe Yasuhara’s Black Tight Killer, 1966) and moody, fatalistic film noir-esque pictures (mudo akushon). The six films collected here fall into the latter camp, with this tone established very clearly in Gangster VIP. Masuda had made his mark as a director for Nikkatsu with his third feature, the 1958 picture Rusty Knife. Masuda’s career with Nikkatsu roughly spans the years of the mukokuseki akushon cycle, beginning not long after the creation of this subtype of films and ending just prior to Nikkatsu’s movement into producing Roman Porno pictures. Like a number of the mukokuseki akushon films, the Outlaw Gangster pictures take some of their narrative cues from Westerns – and particularly, the westerns all’italiana of the period. Masuda once referred to Gangster VIP as ‘a youth film that happens to be set in the yakuza world’ (Masuda, quoted in Schilling, 2007: 56). That approach is certainly evident within the film itself. Like a number of the anti-heroes of the mukokuseki akushon films, Goro is a rebellious figure; dressed in a leather jacket and accompanied by moody songs on the soundtrack, Goro is reminiscent of the characters played by James Dean and Elvis Presley in the American youth pictures of the 1950s. Where earlier period-set yakuza films (jidaigeki) had traditionally featured Westernised villains, the mukokuseki akushon pictures had anti-heroes who were often Westernised, and who went against the strict codes of conduct of the yakuza. (This Westernised depiction of the heroes of these films is also embodied in the Gangster VIP films, and in many other examples of the genre, by the seemingly ubiquitous nightclub sequences, which feature bizarrely Americanised nightclubs populated by sultry lounge singers and whisky-drinking gangsters.) In this way, the films foregrounded themes of inter-generational conflict – much like the American youth pictures of the 1950s and 1960s. The mukokuseki akushon films could oscillate between outlandish and camp (for example, Hasebe Yasuhara’s Black Tight Killer, 1966) and moody, fatalistic film noir-esque pictures (mudo akushon). The six films collected here fall into the latter camp, with this tone established very clearly in Gangster VIP.

In the first film in the series, Goro is arrested and sentenced to three years after being caught stabbing an assassin who murdered the boss of the Mizuhara family. Following his release from prison, Goro saves two young women, including the pretty Yukiko (Matsubara Chieko), from being assaulted by five street thugs who are working for the Ueno clan. Assisted by the Mizuhara family, Goro is thrown into a conflict between the Mizuhara and Ueno clans. He searches for his lover Saeko (Sanjo Yasuko), only to find that she has taken up with an office worker. Later, Goro discovers that Saeto has been forced to work as a prostitute. Meanwhile, Goro finds himself drawn deeper and deeper into the conflict between the Ueno and Mizuhara gangs. In the first film in the series, Goro is arrested and sentenced to three years after being caught stabbing an assassin who murdered the boss of the Mizuhara family. Following his release from prison, Goro saves two young women, including the pretty Yukiko (Matsubara Chieko), from being assaulted by five street thugs who are working for the Ueno clan. Assisted by the Mizuhara family, Goro is thrown into a conflict between the Mizuhara and Ueno clans. He searches for his lover Saeko (Sanjo Yasuko), only to find that she has taken up with an office worker. Later, Goro discovers that Saeto has been forced to work as a prostitute. Meanwhile, Goro finds himself drawn deeper and deeper into the conflict between the Ueno and Mizuhara gangs.

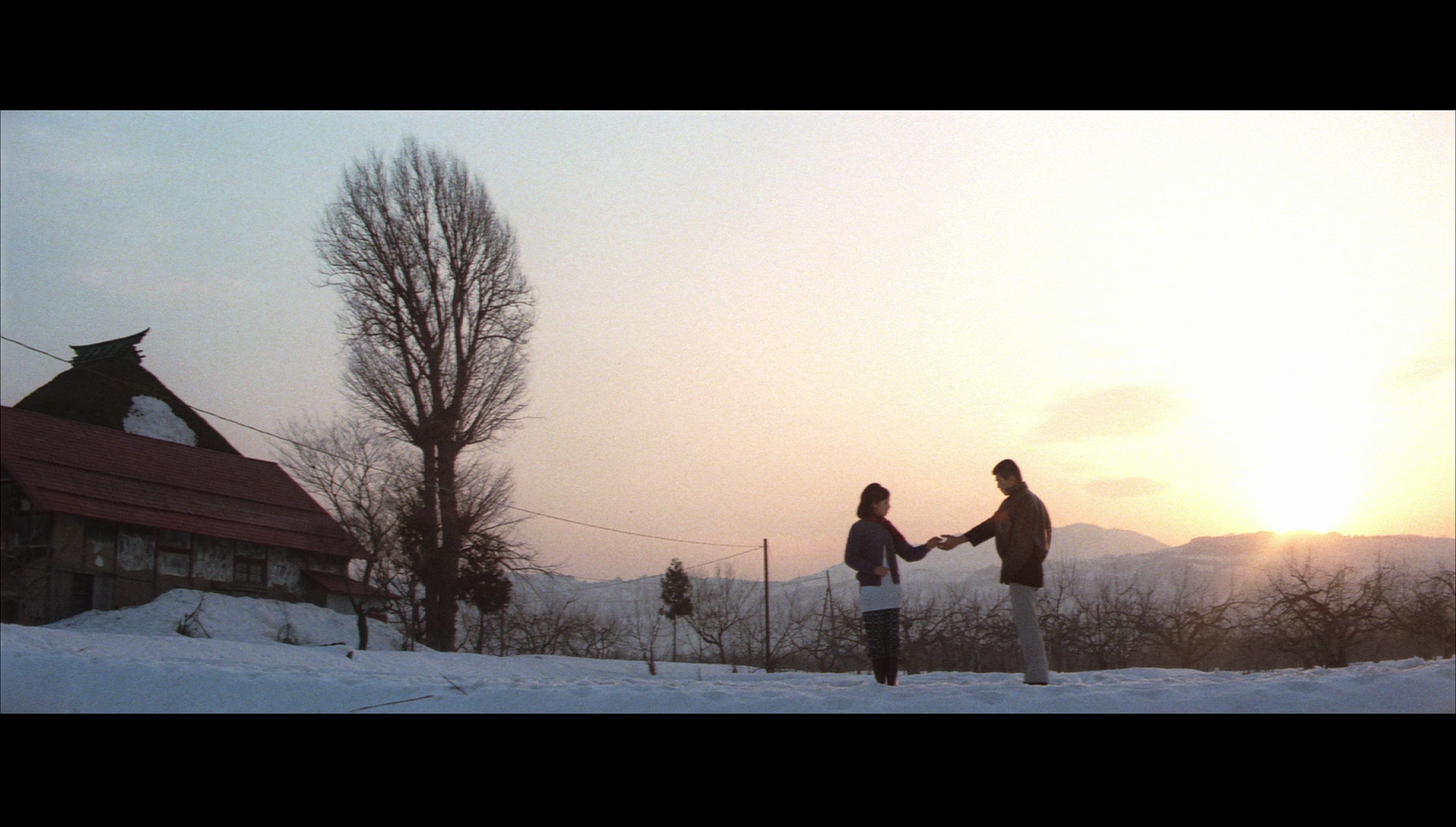

In Gangster VIP 2 (Ozawa Keiichi, 1968), Goro arrives in a snowbound village that is held ransom by gangsters. Goro wishes to live a quiet life away from the yakuza with his lover Yukiko. However, he soon finds this to be impossible: he is once again drawn into the conflicts taking place between rival groups of yakuza when he loses his job as a lumberjack. Financial necessity forces Goro to accept employment within a crime family that is run by a former acquaintance, Kyu. In the third film, Outlaw: Heartless (Ezaki Mio, 1968), Goro is enlisted as part of a crew who have been tasked with extracting a gambling debt from a man named Sawada. When Goro realises that Sawada is in fact the victim of a con, Goro turns the tables and uses the threat of violence to return Sawada’s money to him. However, Sawada is killed and, ridden with guilt, Goro vows to care for Sawada’s desperately ill wife Aki. Meanwhile, Sawada’s brother is convinced that Goro was responsible for the death of Sawada and vows to take revenge against him.  The fourth film, Outlaw: Goro the Assassin (Ozawa Keiichi, 1968) finds Goro again trying to flee from his past as a yakuza and live a normal life in a remote part of Japan. However, he finds that his reputation leads him to becoming drawn into a turf war between two rival yakuza clans. The fourth film, Outlaw: Goro the Assassin (Ozawa Keiichi, 1968) finds Goro again trying to flee from his past as a yakuza and live a normal life in a remote part of Japan. However, he finds that his reputation leads him to becoming drawn into a turf war between two rival yakuza clans.

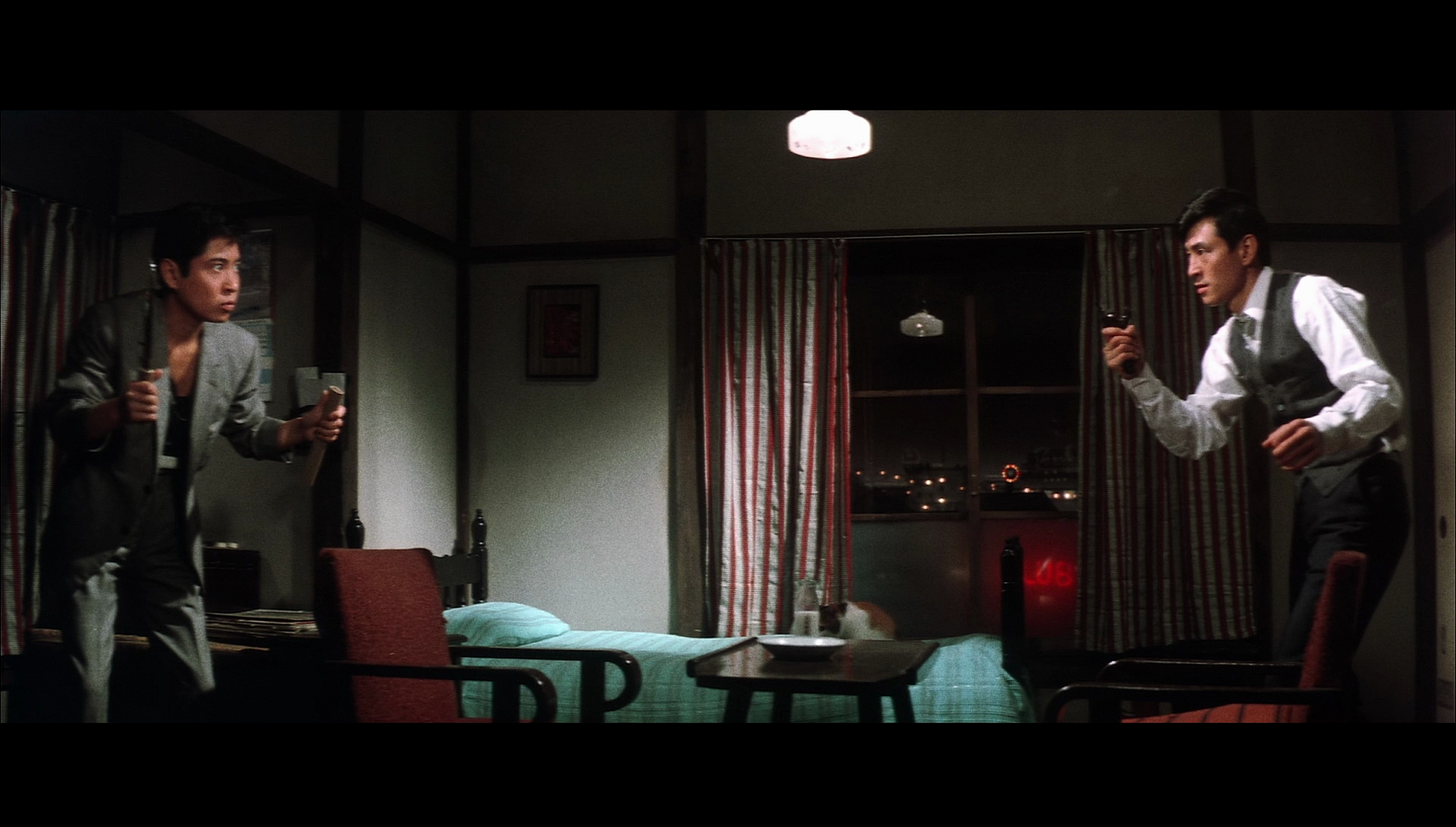

In Outlaw: Black Dagger (Ozawa Keiichi, 1968), Goro is introduced in a violent street fight which results in the death of his lover Yuri, who Goro believed to be leaving via train for a better life elsewhere in Japan. Yuri dies in Goro’s arms, her death symbolising the end of Goro’s dream of escaping the yakuza. The yakuza who killed her, the death blow accidental and intended for Goro, becomes obsessed with Yuri, seeing her likeness in a nurse; Goro also encounters the same nurse and sees in her something that reminds him of Yuri. Goro and his nemesis orbit round the nurse, leading to an inevitable showdown. In the final film, Outlaw: Kill (Ozawa Keiichi, 1969), following an attempt on his life Matsunaga, the head of a yakuza clan, is arrested by the police and sentenced to seven years in prison. His enemies see Matsunaga’s arrest as an excuse to seize his territories. Goro becomes inevitably drawn into this conflict, taking under his wing a younger yakuza and working for the acting head of the Iriezaki family, who happens to be an old friend of Goro’s.  The mukokuseki akushon pictures often featured young, Westernised anti-heroes who would go against the corrupt patriarchs of yakuza clans. Often, clans that embodied traditional methodologies and outlooks would be shown to be consumed by modern ‘corporate’ crime dynasties. This formula is present throughout the Outlaw Gangster films. There’s a sense that the mukokuseki akushon pictures were often deeply formulaic, and the stories of some of them have a tendency to blur into one big narrative; the six films contained here are no exception to this, with a recurring set of narrative paradigms appearing throughout the films. Chief amongst these is an early scene in each of the films, common to other examples of the mukokuseki akushon films, in which the anti-hero Goro protects a young woman (or group of young women) from the unwanted sexual attentions of a yakuza (or small group of yakuza). In each film, Goro displays a romantic attachment to a beautiful young woman, an outsider to the yakuza who represents potential for escape from that world, but resists his feelings for fear that he might drag his lover into the underworld. He (and she) wrestles with his feelings, attempting to explain to her (like Alan Ladd in George Steven’s Shane, 1953) that his way of life is a brand from which he cannot escape, and by which she may become ‘tainted’ if she continues to associate with him. There’s often a none-too-subtle tension between this beautiful young woman – an innocent – and a more experienced ‘fallen’ woman, which suggests that the films are driven by the madonna/whore dualism. In the first film, this manifests itself in the opposition between the naïve Yukiko and Saeko, Goro’s more experienced lover who works as a prostitute. In Gangster VIP 2, Yukiko vows that in order to overcome the couple’s financial difficulties, she will work in a hot springs establishment. She is utterly innocent of the connotations of such employment, until Goro tells her exactly what will be expected from her and refuses to allow her to go. Later, whilst extorting one such establishment, Goro discovers a young woman who at the start of the film, he saved from being assaulted by gangsters. Having fallen on hard times, she has been forced into working as a prostitute; her experiences as a ‘fallen woman’ are contrasted directly with those of Yukiko. The mukokuseki akushon pictures often featured young, Westernised anti-heroes who would go against the corrupt patriarchs of yakuza clans. Often, clans that embodied traditional methodologies and outlooks would be shown to be consumed by modern ‘corporate’ crime dynasties. This formula is present throughout the Outlaw Gangster films. There’s a sense that the mukokuseki akushon pictures were often deeply formulaic, and the stories of some of them have a tendency to blur into one big narrative; the six films contained here are no exception to this, with a recurring set of narrative paradigms appearing throughout the films. Chief amongst these is an early scene in each of the films, common to other examples of the mukokuseki akushon films, in which the anti-hero Goro protects a young woman (or group of young women) from the unwanted sexual attentions of a yakuza (or small group of yakuza). In each film, Goro displays a romantic attachment to a beautiful young woman, an outsider to the yakuza who represents potential for escape from that world, but resists his feelings for fear that he might drag his lover into the underworld. He (and she) wrestles with his feelings, attempting to explain to her (like Alan Ladd in George Steven’s Shane, 1953) that his way of life is a brand from which he cannot escape, and by which she may become ‘tainted’ if she continues to associate with him. There’s often a none-too-subtle tension between this beautiful young woman – an innocent – and a more experienced ‘fallen’ woman, which suggests that the films are driven by the madonna/whore dualism. In the first film, this manifests itself in the opposition between the naïve Yukiko and Saeko, Goro’s more experienced lover who works as a prostitute. In Gangster VIP 2, Yukiko vows that in order to overcome the couple’s financial difficulties, she will work in a hot springs establishment. She is utterly innocent of the connotations of such employment, until Goro tells her exactly what will be expected from her and refuses to allow her to go. Later, whilst extorting one such establishment, Goro discovers a young woman who at the start of the film, he saved from being assaulted by gangsters. Having fallen on hard times, she has been forced into working as a prostitute; her experiences as a ‘fallen woman’ are contrasted directly with those of Yukiko.

In attempting to persuade Yukiko away from becoming involved with himself and thus being sucked into the yakuza life, Goro delivers the self-annihilating rhetoric which seems to be a structuring paradigm of many of Nikkatsu’s yakuza pictures of the period. ‘You don’t get it’, Goro tells Yukiko in Gangster VIP, ‘The free world is a dreadful place [….] I’m a dreadful guy’. However, women are drawn inevitably to him: later in the film Saeko observes, ‘Even though we know you’re yakuza we still fall in love with you. It’s we women who are fools’. As in many other examples of this subgenre, the ‘pure’ woman tries to remind the anti-hero, Goro, that he hasn’t been irrevocably tainted by his years in the yakuza gangs: ‘You’re not really yakuza’, Yukiko tells him before clarifying, ‘You are yakuza, but in your heart you aren’t’. In attempting to persuade Yukiko away from becoming involved with himself and thus being sucked into the yakuza life, Goro delivers the self-annihilating rhetoric which seems to be a structuring paradigm of many of Nikkatsu’s yakuza pictures of the period. ‘You don’t get it’, Goro tells Yukiko in Gangster VIP, ‘The free world is a dreadful place [….] I’m a dreadful guy’. However, women are drawn inevitably to him: later in the film Saeko observes, ‘Even though we know you’re yakuza we still fall in love with you. It’s we women who are fools’. As in many other examples of this subgenre, the ‘pure’ woman tries to remind the anti-hero, Goro, that he hasn’t been irrevocably tainted by his years in the yakuza gangs: ‘You’re not really yakuza’, Yukiko tells him before clarifying, ‘You are yakuza, but in your heart you aren’t’.

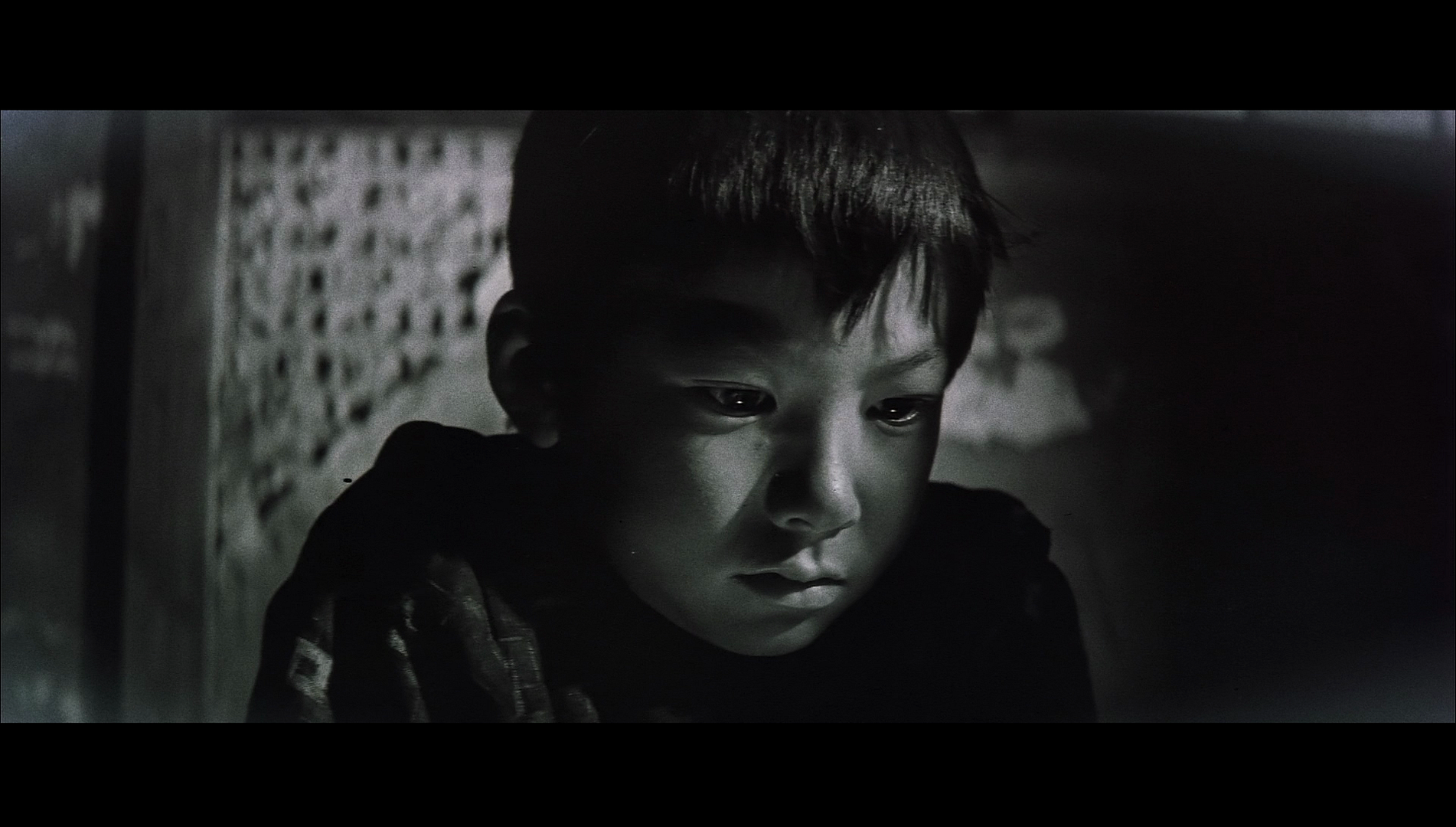

Gangster VIP begins with a monochrome montage that is repeated at the start of Gangster VIP 2, and which establishes the events in Goro’s youth that led him to a life of crime. In this sequence, we are presented with images that show Goro and his young sister Momoko waiting in the cold whilst their mother, a prostitute, ‘services’ one of her clients. The mother is soon shown dead, leaving Goro to fend for himself and Momoko. Momoko is then shown to die, and Goro is left to live on the streets by himself. He is caught stealing and thrown into juvenile detention, where he escapes owing to the help of an older boy. This flashback sequence underpins Goro’s dog-eat-dog worldview: ‘Akabashi is really cold’, Goro tells Saeko in the first film after he discovers she has been forced to work as a prostitute, ‘As kids we didn’t get to eat much. What else can you do when your heart gives in to that coldness?’  Another recurring element within this group of films is the young couple who seem to be on the verge of breaking away from the yakuza lifestyle, and whose departure from this way of life Goro attempts to hasten. In the first film, Gangster VIP, this is shown through a subplot involving a young yakuza, Takeo (Hamada Mitsuo), and his lover Kimiko (Kitabayashi Sanae). Kimiko’s father is concerned about her relationship with Takeo, telling his daughter that ‘A yakuza member doesn’t have a hometown. Like people who don’t know their lineage or where they are born. Or people in Tokyo who have lost all their family’. The concept of a ‘hometown’ – a place in which one has roots and to which one may return – takes on a symbolic importance throughout this film, and Goro advises Takeo to leave the yakuza life, to return to his hometown. Kimiko proposes leaving with Takeo; at the train station, whilst Kimiko is separated from Takeo, buying provisions for their trip, she glances back at her lover and sees a group of yakuza descend upon Takeo, killing him before he can board the train home. It’s a powerful sequence, extremely well staged. Another recurring element within this group of films is the young couple who seem to be on the verge of breaking away from the yakuza lifestyle, and whose departure from this way of life Goro attempts to hasten. In the first film, Gangster VIP, this is shown through a subplot involving a young yakuza, Takeo (Hamada Mitsuo), and his lover Kimiko (Kitabayashi Sanae). Kimiko’s father is concerned about her relationship with Takeo, telling his daughter that ‘A yakuza member doesn’t have a hometown. Like people who don’t know their lineage or where they are born. Or people in Tokyo who have lost all their family’. The concept of a ‘hometown’ – a place in which one has roots and to which one may return – takes on a symbolic importance throughout this film, and Goro advises Takeo to leave the yakuza life, to return to his hometown. Kimiko proposes leaving with Takeo; at the train station, whilst Kimiko is separated from Takeo, buying provisions for their trip, she glances back at her lover and sees a group of yakuza descend upon Takeo, killing him before he can board the train home. It’s a powerful sequence, extremely well staged.

Throughout the films, Goro asserts a moral code that supercedes the code of the yakuza. In the third film, Outlaw: Heartless, Goro approaches Sawada (before discovering how Sawada has been victimised) and demands that Sawada return the money that Goro’s bosses claim Sawada owes to them. Goro apologises, telling Sawada ‘I have no obligation [….] I have no choice’. However, when Goro realises that Sawada is the victim of a long con perpetrated by the yakuza bosses, Goro turns the tables on his employers, using violence to extort money from them which he then passes on to Sawada’s widow Aki as recompense.  The first film, in particular, shows the influence of the westerns all’italiana, Masuda staging the moments of violence and conflict via juxtapositions of long shots and close-ups, the onscreen action accompanied by a Morricone-style score that makes strong use of a trumpet-based deguello. The influence of Westerns continues in Gangster VIP 2, despite the change in director. Goro’s arrival in a snowbound village, held ransom by gangsters, at the start of the film recalls such icy Westerns as Andre de Toth’s Day of the Outlaw (1959). Gangster VIP 2 features a narrative paradigm familiar from many Westerns (including Clint Eastwood’s much later film Unforgiven, 1992) of the gunslinger who is attempting to leave behind his life of violence, only to find himself drawn back into it by the machinations of fate and by his reputation, which precedes him. Introduced to the head of one of the rival gangs, Kyu, Goro discovers that his reputation as ‘Goro the Asassin’ is difficult to escape: ‘I’m sure you’ve heard the rumours about him’, Kyu tells the others before suggesting to Goro that he is surprised ‘Goro the Assassin’ has chosen to live a life of menial labour. ‘Even though you’re Goro the Assassin, it’s laughable that you’re out there hauling boxes like a workhorse’, Kyu observes in reference to Goro’s new employment. ‘I need to make money, but not by being a yakuza’, Goro responds, ‘I don’t go that way anymore’. However, Goro finds that necessity forces him once again to ‘go that way’. Reasoning that ‘I can’t stand being hungry’, Goro accepts the money offered to him by the gangster Kyu, suggesting that ‘Now I have to put my life on the line. It’s a bitter thing to grasp. But I’ll take it’. In this second film in the series, the previously mentioned young woman who turns to prostitution observes, in reference to her own situation but also alluding to Goro’s decision to return to gangsterdom, that ‘Once a person falls this far, it’s too late’. However, Goro expresses a belief that it’s never too late to escape from such circumstances: observing that ‘I’m not that different from you’ owing to his work as a gangster, Goro says that he has struggled to ‘return to normal life. It’s hard. But if you think it’s impossible, your done for’. The first film, in particular, shows the influence of the westerns all’italiana, Masuda staging the moments of violence and conflict via juxtapositions of long shots and close-ups, the onscreen action accompanied by a Morricone-style score that makes strong use of a trumpet-based deguello. The influence of Westerns continues in Gangster VIP 2, despite the change in director. Goro’s arrival in a snowbound village, held ransom by gangsters, at the start of the film recalls such icy Westerns as Andre de Toth’s Day of the Outlaw (1959). Gangster VIP 2 features a narrative paradigm familiar from many Westerns (including Clint Eastwood’s much later film Unforgiven, 1992) of the gunslinger who is attempting to leave behind his life of violence, only to find himself drawn back into it by the machinations of fate and by his reputation, which precedes him. Introduced to the head of one of the rival gangs, Kyu, Goro discovers that his reputation as ‘Goro the Asassin’ is difficult to escape: ‘I’m sure you’ve heard the rumours about him’, Kyu tells the others before suggesting to Goro that he is surprised ‘Goro the Assassin’ has chosen to live a life of menial labour. ‘Even though you’re Goro the Assassin, it’s laughable that you’re out there hauling boxes like a workhorse’, Kyu observes in reference to Goro’s new employment. ‘I need to make money, but not by being a yakuza’, Goro responds, ‘I don’t go that way anymore’. However, Goro finds that necessity forces him once again to ‘go that way’. Reasoning that ‘I can’t stand being hungry’, Goro accepts the money offered to him by the gangster Kyu, suggesting that ‘Now I have to put my life on the line. It’s a bitter thing to grasp. But I’ll take it’. In this second film in the series, the previously mentioned young woman who turns to prostitution observes, in reference to her own situation but also alluding to Goro’s decision to return to gangsterdom, that ‘Once a person falls this far, it’s too late’. However, Goro expresses a belief that it’s never too late to escape from such circumstances: observing that ‘I’m not that different from you’ owing to his work as a gangster, Goro says that he has struggled to ‘return to normal life. It’s hard. But if you think it’s impossible, your done for’.

The theme of the impossibility of escaping from one’s past runs throughout the films. Like Shane declares in George Stevens’ Shane, ‘Right or wrong, it’s a brand. A brand that sticks. There’s no going back’. This theme comes to the foreground in Goro the Assassin, which is arguably the bleakest and most fatalistic of the films. Goro seeks refuge in Ishihama, attempting to settle in a part of Japan where his reputation as ‘Goro the Assassin’ is not recognised. However, he finds that this is perhaps impossible. The film begins with a street fight in which a friend of Goro’s is badly wounded whilst saving Goro’s life. The pair are captured by the police and imprisoned. Goro receives parole and is forced to leave his desperately ill friend. As he leaves, Goro promises his friend that ‘This time we’ll be really legit’. However, Goro’s buddy dies, and Goro waits outside the prison as the coffin is carried out; nobody is waiting to eollect the body. We hear Goro narrate, telling us that this is an example of ‘back gate parole’, for ‘those who die in prison and whose families never claim their bodies’. Taking a menial job in Ishihama, Goro finds himself drawn into a territorial dispute between two rival crime families, the repetition of his nickname ‘Goro the Assassin’ and the fascination exhibited by the others in relation to Goro’s previous ‘exploits’ as a yakuza recalling Clint Eastwood’s later Western Unforgiven and the ways in which Will Munny’s reputation as a gunslinger dog him in that film. In one scene, Goro encounters a group of yakuza who are harassing a woman. The yakuza remind Goro of his nickname ‘Goro the Assassin’ and mock his current status – ‘working in a hotel, pretending to be on the level’. Goro ushers the group outside, where they beat him and pin his hands to a wall with knives.  This fourth film is also the one in which the ante is clearly upped in terms of sexual content, and from this picture onwards the films begin to show some of the fascination with sex, fetishism and various outlets of sexuality that would become the core of the Roman Porno films that Nikkatsu made in the 1970s. Here, in Goro the Assassin, Goro finds a theatre that has, during his time in prison, been converted into a strip club. In the subsequent film, Black Dagger, Goro is reunited with his former lover Saeko; Saeko’s husband is blackmailed by Yasumoto, the head of one of the yakuza clans, to essentially pimp Saeko to Yasumoto. Yasumoto cruelly rapes Saeko before breaking her husband’s fingers, using a pipe to bend the fingers backwards in a cring-enducing moment of sadism. The sexual content is amplified in the final film, Kill; this film features a deeply disturbing rape scene in which a senior yakuza is shown with a woman who is bound to her bed, a dildo at the foot of the bed. The camera lingers on the woman’s face as she prepares for the yakuza’s cruel ‘punishment’. The sequence is elliptical, in the sense that it avoids nudity or any overt depiction of sexual sadism, but direct in terms of its connotations. In retrospect, the progression of the Goro pictures to this point, from the relatively chaste first film to the more brutal and sleazy final films of the series, seems to foreshadow Nikkatsu’s subsequent transition into the production of sex films. This fourth film is also the one in which the ante is clearly upped in terms of sexual content, and from this picture onwards the films begin to show some of the fascination with sex, fetishism and various outlets of sexuality that would become the core of the Roman Porno films that Nikkatsu made in the 1970s. Here, in Goro the Assassin, Goro finds a theatre that has, during his time in prison, been converted into a strip club. In the subsequent film, Black Dagger, Goro is reunited with his former lover Saeko; Saeko’s husband is blackmailed by Yasumoto, the head of one of the yakuza clans, to essentially pimp Saeko to Yasumoto. Yasumoto cruelly rapes Saeko before breaking her husband’s fingers, using a pipe to bend the fingers backwards in a cring-enducing moment of sadism. The sexual content is amplified in the final film, Kill; this film features a deeply disturbing rape scene in which a senior yakuza is shown with a woman who is bound to her bed, a dildo at the foot of the bed. The camera lingers on the woman’s face as she prepares for the yakuza’s cruel ‘punishment’. The sequence is elliptical, in the sense that it avoids nudity or any overt depiction of sexual sadism, but direct in terms of its connotations. In retrospect, the progression of the Goro pictures to this point, from the relatively chaste first film to the more brutal and sleazy final films of the series, seems to foreshadow Nikkatsu’s subsequent transition into the production of sex films.

Video

All of the films are presented in their original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec, and all of the presentations take up around 20Gb of space on their respective discs. The first film’s monochrome opening is crisp, with strong mid-tones and excellent contrast. This is carried over into the colour photography of the rest of the films. (However, the highlights in Black Dagger seem a little ‘hotter’ than those in the rest of the films, with the contrast seeming a little bolder in this particular film – perhaps a product of the source materials used for the presentation.) Colour consistency is good throughout, and the source materials for all of the films are in good shape, with minimal damage present (in the form of very infrequent white flecks and specks). There’s some softness at the edges of the frame, a characteristic of the anamorphic lenses used in many Japanese productions of this vintage and therefore a product of the original photography. All of the films are presented in their original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec, and all of the presentations take up around 20Gb of space on their respective discs. The first film’s monochrome opening is crisp, with strong mid-tones and excellent contrast. This is carried over into the colour photography of the rest of the films. (However, the highlights in Black Dagger seem a little ‘hotter’ than those in the rest of the films, with the contrast seeming a little bolder in this particular film – perhaps a product of the source materials used for the presentation.) Colour consistency is good throughout, and the source materials for all of the films are in good shape, with minimal damage present (in the form of very infrequent white flecks and specks). There’s some softness at the edges of the frame, a characteristic of the anamorphic lenses used in many Japanese productions of this vintage and therefore a product of the original photography.

The films seem to be shot predominantly with short focal lengths, which result in a very strong depth of field that is communicated nicely in these presentations. (The wide-angle lenses used in Japanese films of this era also featured noticeable barrel distortion, which is something that is also present throughout these films.) Finally, the presentations display the characteristic structure of 35mm film, resulting in a pleasingly ‘organic’ presentation across all six films.

Audio

Audio is presented in each casevia a Japanese LPCM 1.0 mono track, with accompanying English subtitles (optional). The audio tracks for all films are clear throughout and ‘punchy’ when they need to be. There’s some wow and flutter audible in the first film, which is noticeable particularly during quiet scenes; but it’s nothing too distracting. The subtitles are clear, easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows:  DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

Gangster VIP (93:26). - Audio commentary with Jasper Sharp. This is an excellent, thorough commentary, as one might expect from Sharp. Sharp places the film within its various contexts and explores its major motifs. It’s a superb track which is definitely worth a listen, even for the most casual viewer of these films (is there such a viewer?) - Trailer (3:09). - Stills gallery (0:17). Gangster VIP 2 (97:17). - Trailer (2:35). - Stills gallery (0:17). - ‘An Outlaw’s Odyssey’ (37:57). Written and narrated by Kevin Gilvear, this video essay examines the six films in the Burai series. Gilvear discusses the reputation of the series and its relationship with the paradigms of Japanese cinema. It’s a snazzily edited, informative piece. DISC TWO: Heartless (91:44). - Trailer (2:35). - Stills gallery (0:17).  Goro the Assassin (87:11). Goro the Assassin (87:11).

- Trailer (2:57). - Stills gallery (0:18). DISC THREE: Black Dagger (86:19). - Trailer (2:59). - Stills gallery (0:20). Kill (85:57). - Trailer (3:15). - Stills gallery (0:17). Retail copies also include a booklet which contains and interview with Masuda Toshio about the series, and some new articles about the films by Mark Schilling, Kevin Gilvear and Chris D.

Overall

Somewhere between the ‘borderless action’ films of the 1950s and 1960s and the Jitsuroku of the 1970s, the Outlaw Gangster films are fun, exciting films to watch – albeit deeply formulaic. Very little seems to have been written about them, other than the first film in the series, so it’s great to see the profile of the series raised by Arrow’s new Blu-ray boxed set. It’s an excellent release, containing solid presentations of all six features and some good contextual material. Fans of Japanese action cinema will find much to enjoy here, and the set represents very good value for money. References: Schilling, Mark, 2007: No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. Godalming: FAB Press Gangster VIP

Gangster VIP 2

Heartless

Goro the Assassin

Black Dagger

Kill

|

|||||

|