|

The Film

Blood Bath/Operation Titian/Portrait in Terror/Track of the Vampire (Rados Novakovic/Jack Hill/Stephanie Rothman, 1966) Blood Bath/Operation Titian/Portrait in Terror/Track of the Vampire (Rados Novakovic/Jack Hill/Stephanie Rothman, 1966)

Co-produced by Roger Corman, the film most commonly known as Blood Bath began its life as a crime thriller with vague espionage elements that was shot in Yugoslavia in 1963, under the title Operation Titian, by director Rados Novakovic. This film featured input from Corman, who aimed to ensure that the finished picture was suitable for sale to American audiences; this involved insisting that the film was shot in English and demanding the casting of two actors – William Campbell and Patrick Magee – with whom Corman had previously worked. Operation Titian’s focus on espionage and the attempts by vague foreign (Italian) forces to track down a specific painting by Titian (the film’s Hitchcockian ‘Maguffin’), together with its ‘exotic’ Eastern European setting, made it feel like a watered-down pastiche of an Eric Ambler novel.

Finding the completed picture impossible to release in the US, Corman had a different edit assembled which had a stronger sense of pace and featured more forceful use of non-diegetic music. This edit of the film, titled Portrait in Terror, was shown on US television. Meanwhile, in 1966 Corman commissioned Jack Hill and, later, Stephanie Rothman to shoot new footage, reworking the narrative completely and retaining from the original production little other than the ‘travelogue’ footage. This version of the film, titled Blood Bath, featured a completely different narrative in which William Campbell plays Antonio Sordi, a painter who is obsessed with one of his ancestors, and whose desire for his female sitters provokes within him a murderous rage (and, in the footage shot by Rothman, whose activities are nebulously connected to the predations of a vampire within the same city). Blood Bath’s relatively short running time of a little under 70 minutes was expanded with some additional footage for a fourth edit of the film, entitled Track of the Vampire.

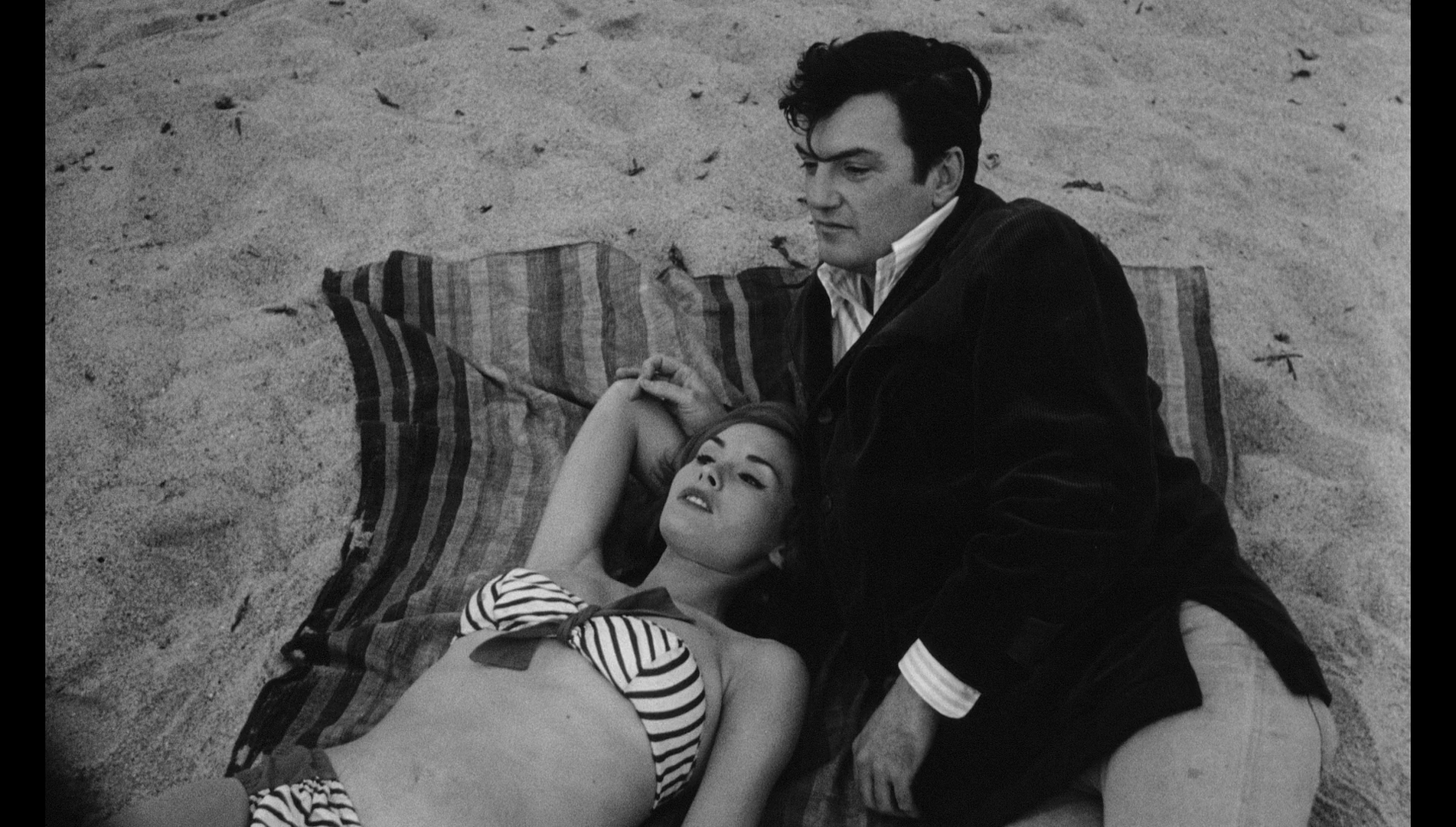

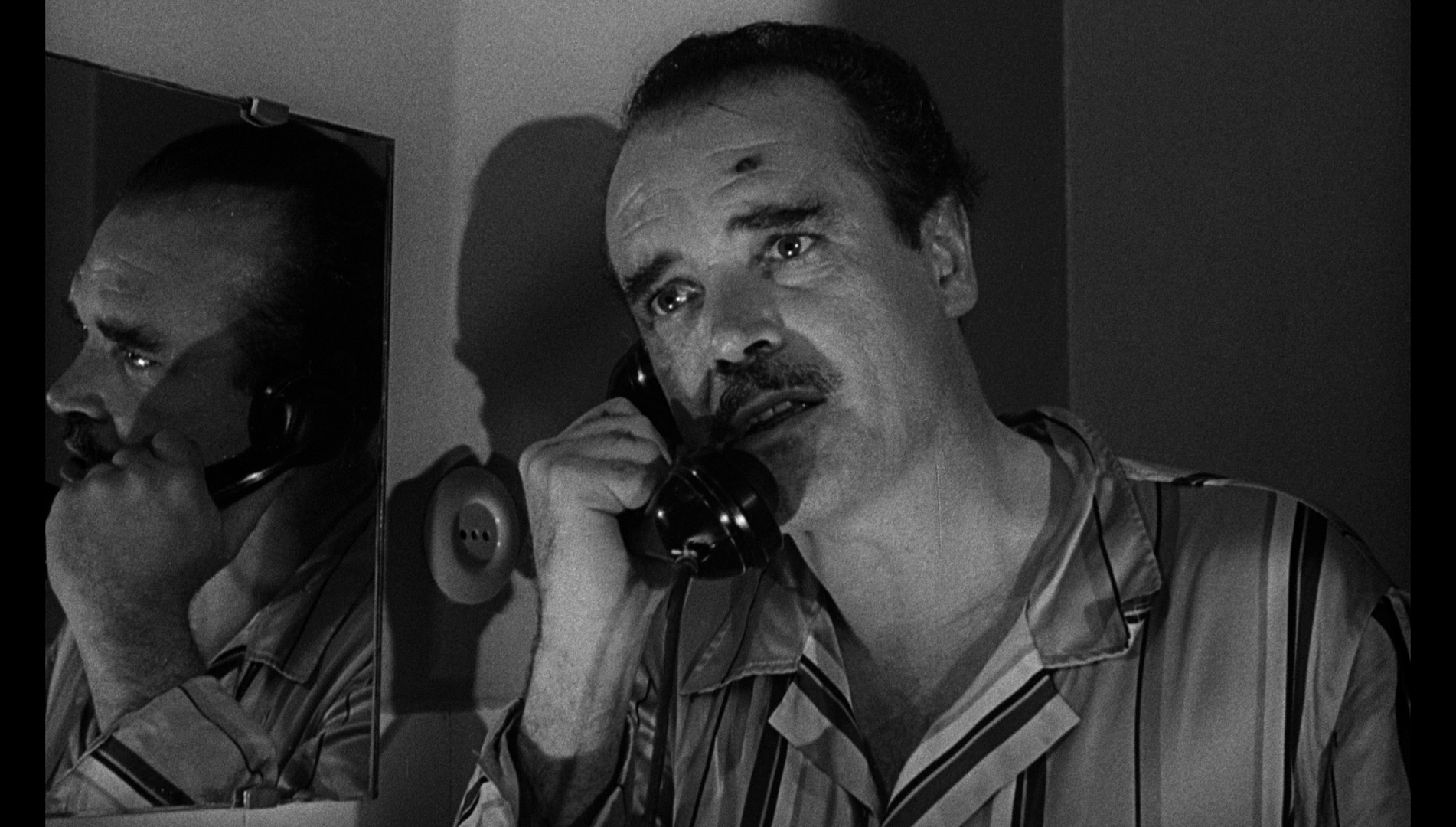

Operation Titian begins with an aeroplane landing in Dubrovnik airport. Disembarking is Mauricio Zaroni (Patrick Magee), who has flown into Dubrovnik from Italy via Belgrade. Meanwhile, at the airport Tony (William Campbell) encounters his former lover Vera (Anna Pavane). Tony is obsessed with Vera and attempts to rekindle their relationship, but Vera is disinterested, having become engaged to a new love, police detective Dzoni.

Receiving his orders from Italy, Zaroni is in Dubrovnik to obtain a stolen painting by the sixteenth century artist Titian. The painting is of the bride of Tony’s ancestor Vlado Sordi. However, Zaroni finds that he has been ‘stiffed’ by his contact in Dubrovnik, who contrary to Zaroni’s expectations demands the money for the painting before handing it over. Attempting to get his hands on the painting, Zaroni murders Ugo, the elderly man who had it in his possession. Dzoni investigates the murder of Ugo; his investigation leads him to Tony, placing Vera in peril. Receiving his orders from Italy, Zaroni is in Dubrovnik to obtain a stolen painting by the sixteenth century artist Titian. The painting is of the bride of Tony’s ancestor Vlado Sordi. However, Zaroni finds that he has been ‘stiffed’ by his contact in Dubrovnik, who contrary to Zaroni’s expectations demands the money for the painting before handing it over. Attempting to get his hands on the painting, Zaroni murders Ugo, the elderly man who had it in his possession. Dzoni investigates the murder of Ugo; his investigation leads him to Tony, placing Vera in peril.

The film opens with shots of a man moving through the city, his passage along its streets filmed in shadow and silhoette, culminating in the theft of the painting around which the subsequent narrative revolves; the sequence is shot with deep focus and canted angles in a manner that seems deliberately reminiscent of Robert Krasker’s expressionistic photography for Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1948). In fact, as noted above, the ‘exotic’ locale and the thriller/espionage plot – vaguely defined as it is – seems like a pastiche of an Eric Ambler novel or a film adaptation thereof – perhaps Norman Foster’s Journey Into Fear (1943) or Jean Negulesco’s Mask of Dimitrios (1944).

Tony’s obsession with Vera and his attempts to woo her back, rather desperately, are juxtaposed with the film’s other plot: Zaroni’s attempts to get his hands on the stolen painting by Titian. (The reasons which Zaroni, who seems to be receiving his orders from Italy, is so urgently trying to obtain the Titian painting are never fully explained.) As even the most casual viewer might expect, the two plots come together towards the end of the film.

At the start of the film, Tony is introduced as a lush, besotted with Vera. (‘I would have stopped drinking forever, if you would have married me’, he tells her.) His attempt to reconnect with Vera symbolises his devotion to the past, which is also foregrounded in his role as ‘assistant curator and direct descendant of the Sordis’: ‘Who has a better right to restore the castle to its splendour?’, Tony asks Vera. (Vera is skeptical of Tony’s claims to be related to Sordi, however.) An American living in Yugoslavia, Tony has a liminal existence and seems desperate to connect to anything that might give him ‘roots’ – whether that be his former relationship with Vera or his tenuous connection with the Sordi family. The painting by Titian represents such a past, and the legend associated with it offers a strange echo of Tony’s own obsession with Vera. Tony tells Vera about the legend: Vlado Sordi, who Tony believes to be one of his ancestors, commissioned Titian to paint the portrait of his beautiful bride; but Sordi discovered that his wife was an adulteress and murdered her with poison before locking himself away for thirty years. ‘It’s a beautiful story, isn’t it?’, Tony suggests. ‘Legends wouldn’t be legends if they were true’, Vera offers in response. At the start of the film, Tony is introduced as a lush, besotted with Vera. (‘I would have stopped drinking forever, if you would have married me’, he tells her.) His attempt to reconnect with Vera symbolises his devotion to the past, which is also foregrounded in his role as ‘assistant curator and direct descendant of the Sordis’: ‘Who has a better right to restore the castle to its splendour?’, Tony asks Vera. (Vera is skeptical of Tony’s claims to be related to Sordi, however.) An American living in Yugoslavia, Tony has a liminal existence and seems desperate to connect to anything that might give him ‘roots’ – whether that be his former relationship with Vera or his tenuous connection with the Sordi family. The painting by Titian represents such a past, and the legend associated with it offers a strange echo of Tony’s own obsession with Vera. Tony tells Vera about the legend: Vlado Sordi, who Tony believes to be one of his ancestors, commissioned Titian to paint the portrait of his beautiful bride; but Sordi discovered that his wife was an adulteress and murdered her with poison before locking himself away for thirty years. ‘It’s a beautiful story, isn’t it?’, Tony suggests. ‘Legends wouldn’t be legends if they were true’, Vera offers in response.

Portrait in Terror offers a more ‘pacy’ cut of the film which eliminates Zaron’s arrival at Dubrovnik airport. This edit of the film cuts more quickly to the chase and features a much more dramatically effective use of music – both diegetic and non-diegetic. (For example, a scene featuring a striptease at a party is, in the Portrait in Terror edit, cut to a big band number that is brassy and sexy, making the scene much more impactful.) In both Operation Titian and Portrait in Terror, however, the film’s thriller plot is lackluster, livened by some interesting photography but hampered by hesitant direction of the actors. However, despite this, it’s tempting to see in Tony’s obsession with his ‘ancestor’ Vlado Sordi (and the morbid legend surrounding the Titian painting) echoes of Corman’s own Gothic horror film The Haunted Palace (1963), an adaptation of H P Lovecraft’s 1941 novella The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, in which Vincent Price’s Charles Dexter Ward becomes obsessed by a portrait of his ancestor Joseph Curwen, and this obsession leads to Ward becoming possessed by Curwen. Watching Operation Titian, the viewer might expect a similar plot development, with Tony becoming possessed by Sordi; however, nothing of the sort takes place in this film, although the story is taken in a similar direction within Hill and Rothman’s revised/reshot horror-themed edits of the film, Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire.

The dialogue for Operation Titian was ‘Americanised’ by Francis Ford Coppola, who visited Yugoslavia following the shooting in 1962 of Dementia 13 for Corman (Stevens, 2003: 26). Jack Hill has suggested that during the shooting of Operation Titian, Coppola – who had been tasked by Corman with overseeing the shooting of what he believed to be a horror film – was ‘spending all of his time’ with his future wife ‘and he didn’t really supervise things’ (Hill, quoted in Waddell, 2009: 31). As a consequence, Corman realised when the film was completed that ‘it was not a horror movie it was just this really lousy suspense thriller called Operation Titian’ (Hill, quoted in ibid.). Corman tasked Hill with ‘salvag[ing] whatever footage you can’, and asked Hill to turn the film into a horror picture (Hill, quoted in ibid.). Hill wrote a script and shot some new footage, making his version of Blood Bath before leaving the picture to shoot his next film, Spider Baby (1967). After Corman finished the film he was shooting in Yugoslavia, The Secret Invasion (1965), he returned to Blood Bath and assigned Stephanie Rothman to the picture; Rothman ‘changed it into a vampire movie’, whereas Hill’s intention was to make the picture into a psychological thriller – ‘so I thought she just messed it up’, Hill later said (Hill, quoted in ibid.: 32). The dialogue for Operation Titian was ‘Americanised’ by Francis Ford Coppola, who visited Yugoslavia following the shooting in 1962 of Dementia 13 for Corman (Stevens, 2003: 26). Jack Hill has suggested that during the shooting of Operation Titian, Coppola – who had been tasked by Corman with overseeing the shooting of what he believed to be a horror film – was ‘spending all of his time’ with his future wife ‘and he didn’t really supervise things’ (Hill, quoted in Waddell, 2009: 31). As a consequence, Corman realised when the film was completed that ‘it was not a horror movie it was just this really lousy suspense thriller called Operation Titian’ (Hill, quoted in ibid.). Corman tasked Hill with ‘salvag[ing] whatever footage you can’, and asked Hill to turn the film into a horror picture (Hill, quoted in ibid.). Hill wrote a script and shot some new footage, making his version of Blood Bath before leaving the picture to shoot his next film, Spider Baby (1967). After Corman finished the film he was shooting in Yugoslavia, The Secret Invasion (1965), he returned to Blood Bath and assigned Stephanie Rothman to the picture; Rothman ‘changed it into a vampire movie’, whereas Hill’s intention was to make the picture into a psychological thriller – ‘so I thought she just messed it up’, Hill later said (Hill, quoted in ibid.: 32).

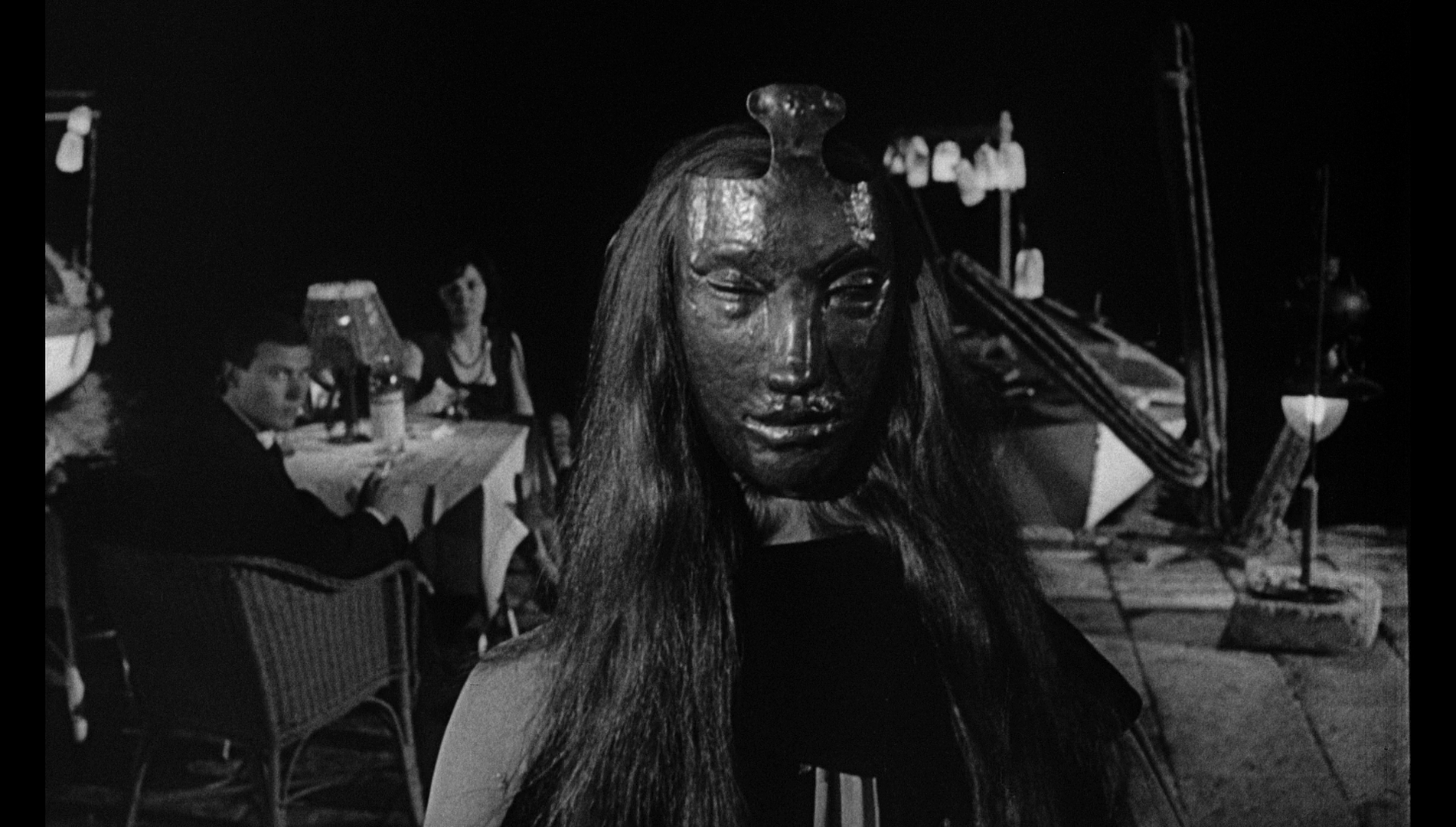

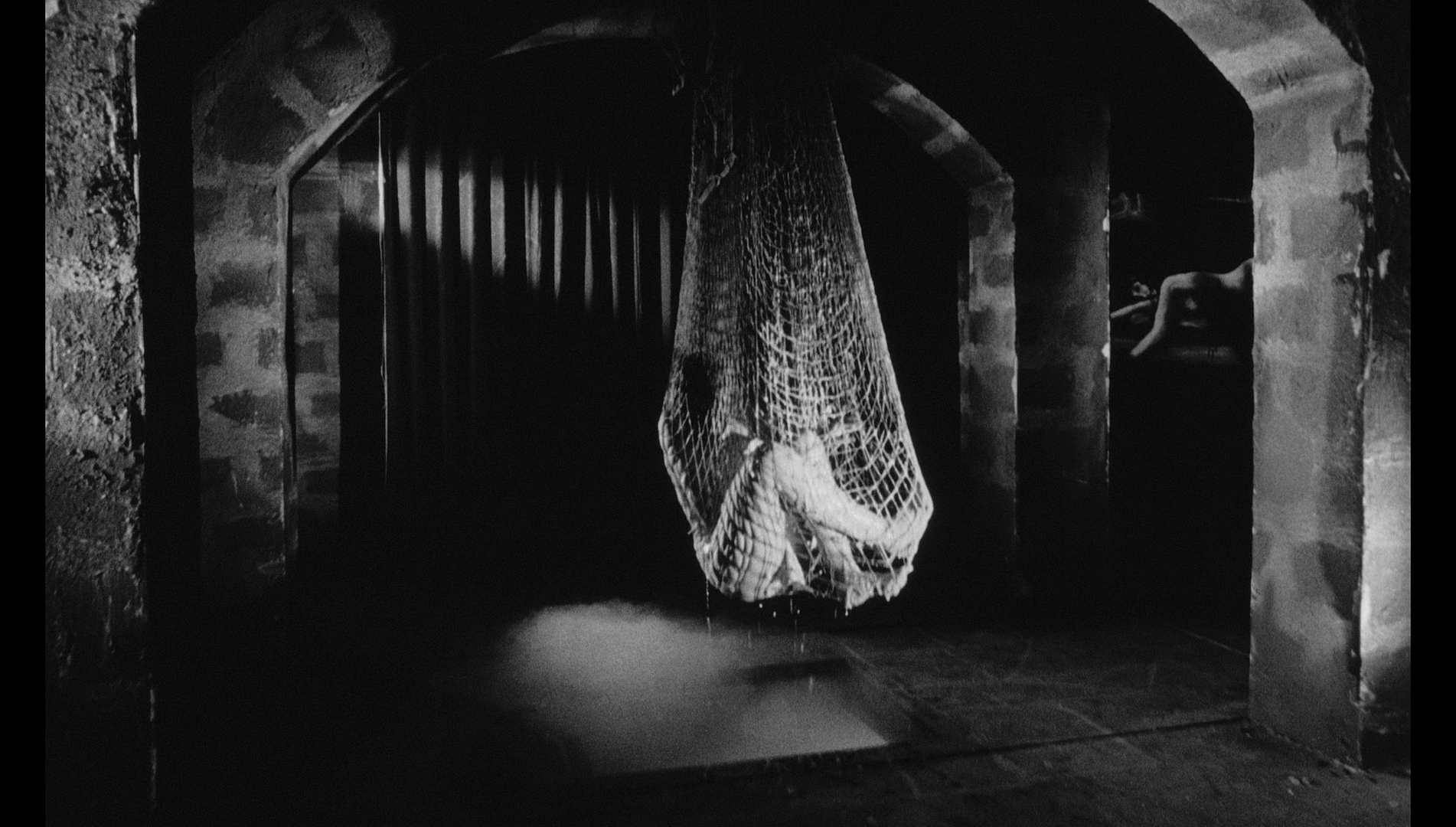

Blood Bath recasts William Campbell as Antonio Sordi, a reclusive artist. Sordi is obsessed with a portrait of Melizza, the lover of his ancestor Erno Sordi. Also a painter, Erno Sordi was burned at the stake for sorcery, his canvases destroyed too, when Melizza was so impressed with the portrait he painted of her that she believed Erno to have captured her soul and imprisoned it within the canvas. When Sordi is approached by a beautiful young woman named Daisy (Marissa Mathes) who admires his paintings, Sordi offers to paint her portrait. They retreat to his studio, where Sordi is overcome with a vision of Melizza and murders Daisy brutally, dipping her dead body in wax and turning her into a statue. With Daisy’s absence, her sister begins to suspect Sordi had a hand in Daisy’s disappearance, and begins to close in on the artist.

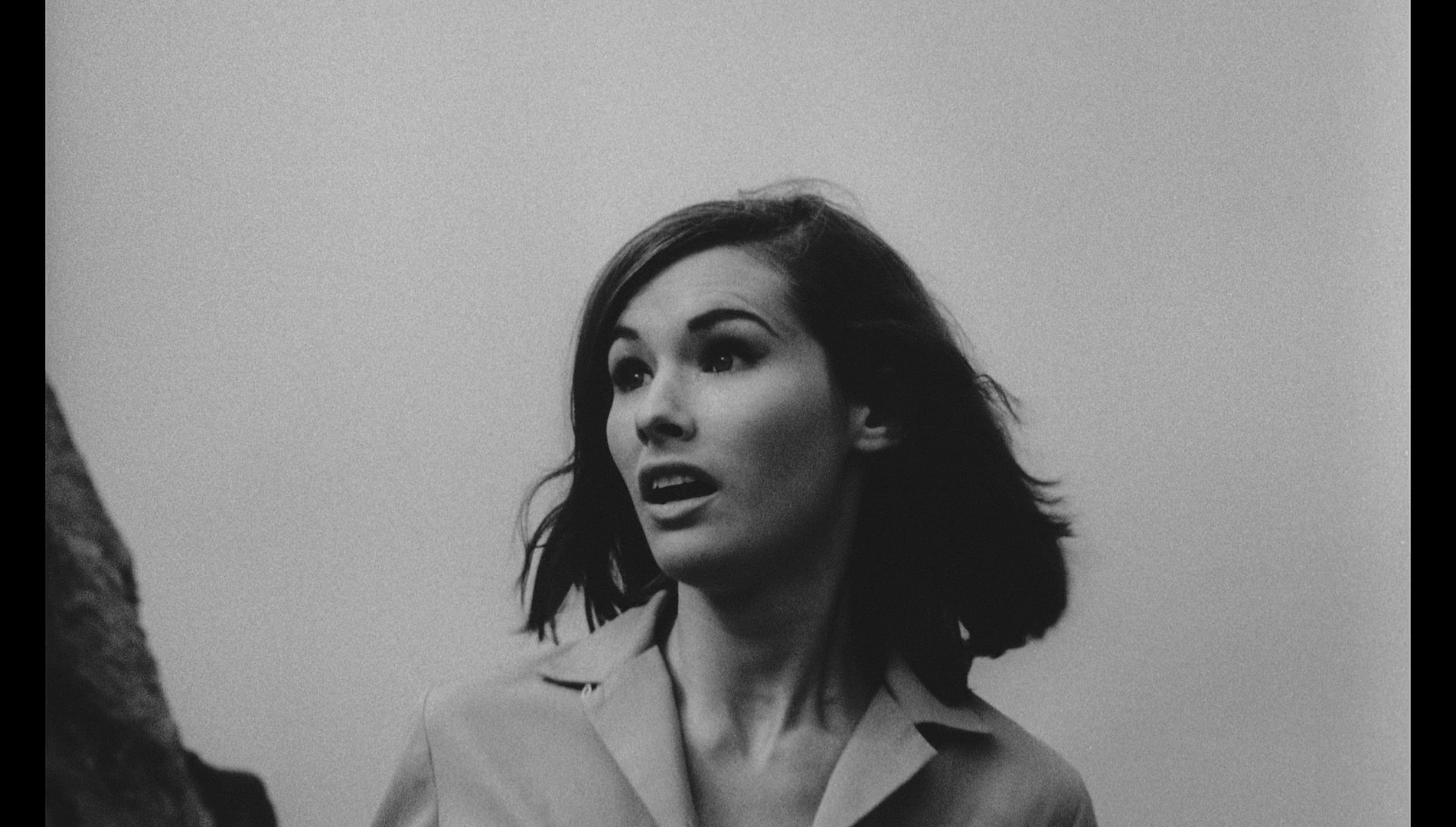

As the film opens, Sordi gazes upon the painted portrait of Melizza, declaring ‘I forgive you for everything, Melizza [….] You must come back to me’. Sordi, we soon find out, has a reputation for painting what are referred to within the film’s dialogue as ‘dead red nudes’: paintings of naked, murdered women. What Sordi’s buyers don’t know are that the paintings are from life. When he meets Daisy on the street, Daisy tells Sordi that his paintings are ‘like looking down from a high place. It frightens you because it makes you realise that you’d like to jump off, shows you the horror in death that you desire’. After they retire to Sordi’s studio, where Sordi offers to paint Daisy, she asks him, ‘Are you going to paint me dead?’ Sordi responds by saying that ‘I never plan a picture. It must be allowed to grow, out of its own natural order’. He murders Daisy, turning her into a wax statue. Later, we are shown Doreen, a female friend of Tony’s who he meets regularly on the beach – but who he refuses to paint. ‘Why don’t you make a pass at me?’, Doreen asks Tony. ‘I have too much respect for you’, Tony says, though we know that the real reason he doesn’t is because his murderous rage is provoked by lust and desire – and he fears that if he were to kiss Doreen, this would result in him murdering her. ‘I don’t want you to respect me, not that kind’, Doreen replies, ‘I want you to love me’. The film’s exploration of an artist who sublimates his desire into art, and whose art leads to murder, may be compared with Herschell Gordon Lewis’ Color Me Blood Red (1965), in which artist Adam Sorge commits murder and, in a bizarre parody of practises within modern art that would become more prevalent with the work of the likes of Gilbert and George in the 1970s and beyond, uses the blood of his victims to paint his ‘masterpieces’. The dipping of the corpses in molten wax, in order to make statues out of them, also recalls Michael Curtiz’s Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), which had also influenced Corman’s previous hybrid of horror film and art world satire A Bucket of Blood (1959). As the film opens, Sordi gazes upon the painted portrait of Melizza, declaring ‘I forgive you for everything, Melizza [….] You must come back to me’. Sordi, we soon find out, has a reputation for painting what are referred to within the film’s dialogue as ‘dead red nudes’: paintings of naked, murdered women. What Sordi’s buyers don’t know are that the paintings are from life. When he meets Daisy on the street, Daisy tells Sordi that his paintings are ‘like looking down from a high place. It frightens you because it makes you realise that you’d like to jump off, shows you the horror in death that you desire’. After they retire to Sordi’s studio, where Sordi offers to paint Daisy, she asks him, ‘Are you going to paint me dead?’ Sordi responds by saying that ‘I never plan a picture. It must be allowed to grow, out of its own natural order’. He murders Daisy, turning her into a wax statue. Later, we are shown Doreen, a female friend of Tony’s who he meets regularly on the beach – but who he refuses to paint. ‘Why don’t you make a pass at me?’, Doreen asks Tony. ‘I have too much respect for you’, Tony says, though we know that the real reason he doesn’t is because his murderous rage is provoked by lust and desire – and he fears that if he were to kiss Doreen, this would result in him murdering her. ‘I don’t want you to respect me, not that kind’, Doreen replies, ‘I want you to love me’. The film’s exploration of an artist who sublimates his desire into art, and whose art leads to murder, may be compared with Herschell Gordon Lewis’ Color Me Blood Red (1965), in which artist Adam Sorge commits murder and, in a bizarre parody of practises within modern art that would become more prevalent with the work of the likes of Gilbert and George in the 1970s and beyond, uses the blood of his victims to paint his ‘masterpieces’. The dipping of the corpses in molten wax, in order to make statues out of them, also recalls Michael Curtiz’s Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), which had also influenced Corman’s previous hybrid of horror film and art world satire A Bucket of Blood (1959).

The film intercuts Sordi’s macabre approach to art with the discussions of a group of bohemian artists who gather in a local pub. (One of these, Abdul, is played by Sid Haig.) These men are experimental artists who rail against formalist/representational art. The blackly comic touch of Jack Hill feels very obvious within these scenes, which use these artists to satirise ideas within modern art. One of the artists, Max (Karl Shanzer), unveils his new painting, a portrait of Daisy. Much to Daisy’s surprise, and the surprise of Max’s friends, the painting is a conventional representational portrait. ‘So you can paint a real picture, after all’, a pleasantly surprised Daisy asserts, ‘It even looks like me!’ ‘I don’t understand this’, Abdul protests, ‘It’s, er... It’s formal’. ‘It’s a joke, a hoax’, one of the other beatniks says. Max fires a paint pellet at the canvas, obliterating the face of Daisy; his friends are impressed by this, moving in closer to study the impact of the paint pellet. ‘Look, millions of tiny little flicks’, one of the beatniks says, ‘Like the universe’. Daisy is unimpressed. ‘That’s my face, Max’, she complains, ‘That isn’t funny’. ‘Of course it’s not funny’, Max replies, ‘It’s brilliant, tremendous’. ‘Well, I think it’s puerile’, Daisy says. ‘What does it matter what you think?’, Max asks, ‘I’m the artist’. Shortly afterwards, in anger Daisy pours a bottle of booze over Max’s head. The alcohol drips from Max’s head onto the piece of paper in front of him, Max and his friends gather round the paper. ‘The film! The composition!’, Max declares in wonder, reflecting on the abstract splashes on the page. In its satirical depiction of the world of bohemian artists, these scenes within the film feel very much like the parodies of modern art within the Tony Hancock film The Rebel (Robert Day, 1961). The film intercuts Sordi’s macabre approach to art with the discussions of a group of bohemian artists who gather in a local pub. (One of these, Abdul, is played by Sid Haig.) These men are experimental artists who rail against formalist/representational art. The blackly comic touch of Jack Hill feels very obvious within these scenes, which use these artists to satirise ideas within modern art. One of the artists, Max (Karl Shanzer), unveils his new painting, a portrait of Daisy. Much to Daisy’s surprise, and the surprise of Max’s friends, the painting is a conventional representational portrait. ‘So you can paint a real picture, after all’, a pleasantly surprised Daisy asserts, ‘It even looks like me!’ ‘I don’t understand this’, Abdul protests, ‘It’s, er... It’s formal’. ‘It’s a joke, a hoax’, one of the other beatniks says. Max fires a paint pellet at the canvas, obliterating the face of Daisy; his friends are impressed by this, moving in closer to study the impact of the paint pellet. ‘Look, millions of tiny little flicks’, one of the beatniks says, ‘Like the universe’. Daisy is unimpressed. ‘That’s my face, Max’, she complains, ‘That isn’t funny’. ‘Of course it’s not funny’, Max replies, ‘It’s brilliant, tremendous’. ‘Well, I think it’s puerile’, Daisy says. ‘What does it matter what you think?’, Max asks, ‘I’m the artist’. Shortly afterwards, in anger Daisy pours a bottle of booze over Max’s head. The alcohol drips from Max’s head onto the piece of paper in front of him, Max and his friends gather round the paper. ‘The film! The composition!’, Max declares in wonder, reflecting on the abstract splashes on the page. In its satirical depiction of the world of bohemian artists, these scenes within the film feel very much like the parodies of modern art within the Tony Hancock film The Rebel (Robert Day, 1961).

In Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire, which simply expands Blood Bath’s running time, there’s a strong Californian sense of place in the buildings and attitudes on display, and this clashes with the Yugoslavia-shot ‘travelogue’ inserts from Operation Titian. The sense of consistency is further hampered by the scenes involving a vampire who is attacking women on the city streets; these scenes disrupt the narrative, and though they offer some striking imagery (a chase that climaxes on a carousel at night; a fight that takes place in a swimming pool, shot via underwater photographer), seem to disrupt the already disjointed narrative. In Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire, which simply expands Blood Bath’s running time, there’s a strong Californian sense of place in the buildings and attitudes on display, and this clashes with the Yugoslavia-shot ‘travelogue’ inserts from Operation Titian. The sense of consistency is further hampered by the scenes involving a vampire who is attacking women on the city streets; these scenes disrupt the narrative, and though they offer some striking imagery (a chase that climaxes on a carousel at night; a fight that takes place in a swimming pool, shot via underwater photographer), seem to disrupt the already disjointed narrative.

Video

On disc one, Operation Titian and Portrait in Terror both take up 23Gb of space each. Operation Titian runs for 95:22 mins; Portrait in Terror runs for 81:23 mins. On disc one, Operation Titian and Portrait in Terror both take up 23Gb of space each. Operation Titian runs for 95:22 mins; Portrait in Terror runs for 81:23 mins.

On disc two, Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire take up 15Gb and 20Gb, respectively. Blood Bath runs for 62:03 mins; Track of the Vampire runs for 79:23 mins.

All four cuts of the film are presented in 1.66:1, in 1080p using the AVC codec.

Ironically enough, for a film that would later be more widely seen in a composite form as Blood Bath or Track of the Vampire, this presentation of Operation Titian – the film’s original edit – is a composite itself. The ‘base’ presentation, a new 2k scan of the existing film materials, looks excellent, with excellent levels of detail and strong contrast levels characterised by defined mid-tones and rich, deep blacks. However, some of the other footage – the footage exclusive to the Operation Titian cut – is presented from an upscaled SD source and looks much more rough around the proverbial edges, with clipped highlights and recurring examples of print damage. The transitions between the new HD restoration and the SD inserts are very noticeable, but this certainly doesn’t mitigate the importance of having this cut of the film, and the re-edited Portrait in Terror cut, included in this Blu-ray release.

The presentations of Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire are much more consistent, though this consistency is undermined slightly by the fact that the footage exclusive to the Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire edits was shot on monochrome film stock with rather different qualities to that used to shoot Operation Titian/Portrait in Terror; the grain structure of the two film stocks is noticeably different, with that used to shoot the new footage of Blood Bath having a coarser structure and handling the contrast between light and dark in a subtly different manner. (Those familiar with black and white 35mm still photography might compare it with the difference between Kodak’s T-Max 400 and their older formula for Tri-X 400 – both monochrome film stocks, but one with a tighter grain structure than the other and a noticeable difference in how contrast is handled.) Both presentations on disc two are sourced predominantly from a fine grain positive, with Track of the Vampire incorporating its exclusive footage from a dupe negative and the climax of Blood Bath being sourced from a noticeable weaker source. Regardless, the presentations of both of these versions of the film are very pleasing throughout, with an excellent level of detail, very good contrast levels and the structure of 35mm film. The presentations of Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire are much more consistent, though this consistency is undermined slightly by the fact that the footage exclusive to the Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire edits was shot on monochrome film stock with rather different qualities to that used to shoot Operation Titian/Portrait in Terror; the grain structure of the two film stocks is noticeably different, with that used to shoot the new footage of Blood Bath having a coarser structure and handling the contrast between light and dark in a subtly different manner. (Those familiar with black and white 35mm still photography might compare it with the difference between Kodak’s T-Max 400 and their older formula for Tri-X 400 – both monochrome film stocks, but one with a tighter grain structure than the other and a noticeable difference in how contrast is handled.) Both presentations on disc two are sourced predominantly from a fine grain positive, with Track of the Vampire incorporating its exclusive footage from a dupe negative and the climax of Blood Bath being sourced from a noticeable weaker source. Regardless, the presentations of both of these versions of the film are very pleasing throughout, with an excellent level of detail, very good contrast levels and the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

With all four cuts of the film, audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. On all four cuts, this is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. With all four cuts of the film, audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. On all four cuts, this is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

With all four versions of the film, audio is clear and audible throughout, with good range. With Operation Titian/Portrait in Terror the audio track is also a composite, and some of the inserts feature noticeable clipping and are a little ‘flat’ at times. On the other hand, Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire don’t suffer from this problem (naturally, as these cuts of the film are, unlike the presentations of Operation Titian and Portrait in Terror, not composites) and feature excellent range throughout.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows:

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

Operation Titian (95:22).

Portrait in Terror (81:23).

DISC TWO:

Blood Bath (62:03).

Track of the Vampire (79:23).

- The Trouble with Titian Revisited’ (81:13). This is an excellent new video essay in which Tim Lucas provides an overview of the film’s production history and discusses the different edits of the picture.

- ‘Bathing in Blood with Sid Haig’ (4:36). Here, Haig talks about Corman’s involvement in Operation Titian and discusses some of the techniques used to shoot the effects sequences. The beach scenes, he reveals, were shot in January, and this is the reason for the lack of closeups in them (‘You can’t do the closeups, because you’d see the goosepimples’).

- ‘Jack Hill on Blood Bath’ (3:06). In this new interview, Hill talks about Corman’s involvement in the film and how Hill came to be hired to direct Blood Bath.

- Gallery (0:28).

Retail copies include one of Arrow’s characteristically excellent booklets with new articles about the film by Anthony Nield, Vic Pratt, Cullen Gallagher and Peter Beckman.

Overall

There are, essentially, two rather different films here – the thriller Operation Titian and the horror picture Blood Bath – and a variant cut of each (Portrait in Terror, which abbreviates Operation Titian’s narrative; and Track of the Vampire, which expands the narrative of Blood Bath). Though there are obvious lapses in consistency in terms of the presentations of these four various edits of this picture owing to them being assembled from a number of different sources (Operation Titian fares the worst owing to a good portion of the film being inserted from an upscaled SD source), the decision to include of all four versions of the film is an excellent one. Blood Bath is arguably the best of the four versions of the film: its horror plot, it could be argued, has more to offer than Operation Titian’s retreading of the narrative paradigms of thrillers in the Eric Ambler mode. In addition, Blood Bath features a dryly funny satire of the art world, and its narrative doesn’t ‘drag’ as much as that of the expanded Track of the Vampire cut. Nevertheless, this excellent set offers the ability to compare and contrast the various edits of this film; the presentations of the films would seem to be the best that could be achieved, given the disparate materials available, and the four edits of the film are accompanied by some superb contextual material: principally, Tim Lucas’ extensive video essay detailing the film’s production history and the differences between the four versions of the picture. This is an excellent – and, dare I say it, exhaustive – release of a fun film and, as a result, it comes with a very strong recommendation. There are, essentially, two rather different films here – the thriller Operation Titian and the horror picture Blood Bath – and a variant cut of each (Portrait in Terror, which abbreviates Operation Titian’s narrative; and Track of the Vampire, which expands the narrative of Blood Bath). Though there are obvious lapses in consistency in terms of the presentations of these four various edits of this picture owing to them being assembled from a number of different sources (Operation Titian fares the worst owing to a good portion of the film being inserted from an upscaled SD source), the decision to include of all four versions of the film is an excellent one. Blood Bath is arguably the best of the four versions of the film: its horror plot, it could be argued, has more to offer than Operation Titian’s retreading of the narrative paradigms of thrillers in the Eric Ambler mode. In addition, Blood Bath features a dryly funny satire of the art world, and its narrative doesn’t ‘drag’ as much as that of the expanded Track of the Vampire cut. Nevertheless, this excellent set offers the ability to compare and contrast the various edits of this film; the presentations of the films would seem to be the best that could be achieved, given the disparate materials available, and the four edits of the film are accompanied by some superb contextual material: principally, Tim Lucas’ extensive video essay detailing the film’s production history and the differences between the four versions of the picture. This is an excellent – and, dare I say it, exhaustive – release of a fun film and, as a result, it comes with a very strong recommendation.

References:

Stevens, Brad, 2003: Monte Hellman: His Life and Films. London: McFarland & Company, Inc

Waddell, Callum, 2009: Jack Hill: The Exploitation and Blaxploitation Master, Film By Film. London: McFarland & Company, Inc

Operation Titian

Blood Bath

Track of the Vampire

|