|

|

Tokyo Mighty Guy AKA Tokyo no abarembô AKA Rambler in the Sunset (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th June 2016). |

|

The Film

Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol 2  Please also see our review of Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol 1 here. Please also see our review of Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol 1 here.

The three films included in this second volume of Nikkatsu-produced pictures come from a slightly later period than the films included in Arrow’s first Nikkatsu Diamond Guys set. The films in that first volume – Voice Without a Shadow (Suzuki Seijun, 1958), Red Pier (Masuda Toshio, 1958) and Guitar Wanderer (Saito Buichi, 1959) – were produced in the late 1950s, during a period in which Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures were evolving. The two earliest films in that set (Voice Without Shadow and Red Pier) featured stunning monochrome photography that emulated the visual paradigms of American films noir (including chiaroscuro lighting, and obtuse angles and compositions), their fusion of elements of Japanese, American and European filmmaking defining the ‘borderless’ approach of Nikkatsu’s action films. The final picture in the first volume, Guitar Wanderer, is a stark contrast to the first two films, exemplified Nikkatsu’s evolving and highly flexible approach; this film features vibrant colour photography, a mixture of music and comedy, and a narrative (and Westernised hero) with a ‘lighter touch’ than its forebears and which bears comparisons with American youth films produced during the same era – particularly those of Elvis Presley. The three films in this second volume follow on from Guitar Wanderer, in the sense that all three pictures feature vibrant colour photography, a youth-oriented focus and ‘lighter’ narratives punctuated by moments of broad humour. The films included in this second volume are Saito Buichi’s Tokyo Mighty Guy (1960), Nakahira Ko’s Danger Pays (1962) and Noguchi Haruyasa’s Murder Unincorporated (1965).  Starring maito gai (‘mighty guy’) Kobayashi Akira as Jiro, Tokyo Mighty Guy (Saito Buichi, 1960) was one of a large number of films that director Saito Buichi made for Nikkatsu. At the time, Kobayashi was of course one of Nikkatsu’s most popular stars. Jiro has recently graduated from university in France, and his friend Matsuda (Asaoka Ruriko), who is still a student, is clearly in love with him. Jiro’s family run a modest restaurant which specialises in French cuisine, whilst Matsuda’s family own and operate a traditional bathhouse. However, Matsuda’s love for Jiro is complicated by the fact that she is engaged to the son of a wealthy businessman. Starring maito gai (‘mighty guy’) Kobayashi Akira as Jiro, Tokyo Mighty Guy (Saito Buichi, 1960) was one of a large number of films that director Saito Buichi made for Nikkatsu. At the time, Kobayashi was of course one of Nikkatsu’s most popular stars. Jiro has recently graduated from university in France, and his friend Matsuda (Asaoka Ruriko), who is still a student, is clearly in love with him. Jiro’s family run a modest restaurant which specialises in French cuisine, whilst Matsuda’s family own and operate a traditional bathhouse. However, Matsuda’s love for Jiro is complicated by the fact that she is engaged to the son of a wealthy businessman.

One day, a car carrying Ipponyari (Ogawa Toranosuke), a former prime minister, crashes into Jiro’s family’s restaurant. Non-plussed by Ipponyari’s background and status, Jiro demands an apology, angering the politician. Later, a group of gangsters visit Jiro’s family’s restaurant, offering to help Jiro seek recompense form Ipponyari. Jiro dismisses them. When the same gangsters approach Ipponyari, Jiro comes to the old man’s aid, and the pair soon develop a friendship: Ipponyari has come to respect Jiro’s courage and independence – his edokko spirit. Ipponyari comes to Jiro’s family’s aid, sponsoring them by having their restaurant rebuilt and remodeled. The new restaurant is a swish affair, attracting a more prestigious clientele, including the French ambassador. Jiro achieves a newfound fame, resulting in him being approached by a woman, who demands that he masquerade as her lover in order to dissuade three of her suitors. Jiro’s edokko spirit prevents him from refusing to come to the aid of a woman who needs help, but his decision to assist this woman alienates him from Matsuda. Meanwhile, another young woman, Toshi, falls pregnant by her lover, a man named Kiyoshi. When Kiyoshi abandons Toshi, Jiro comes to her aid and attempts to track down, eventually discovering that ‘Kiyoshi’ is an assumed name and the man is really Asai Ryuzo (Aihara Kyosuke), the son and heir of a wealthy business tycoon. Ryuzo also happens to be the fiancé of Matsuda, and his impending marriage to her is part of a dastardly ruse by the Asai family to get their hands on Matsuda’s family’s bathhouse before turning it ‘into a big Turkish bath’.  Jiro is introduced in a wrestling gym whilst his admirer, Matsuda, watches on from her fencing class, which is taking place in the other half of the gymnasium. Their relationship is deftly sketched in the film’s opening sequences: Matsuda is in love with Jiro, though she stops just a little short of declaring this to him, whilst Jiro – who is slightly older – regards her as little more than a child (‘Of course, you’re still a kid to me’, he tells her when she reveals that she is engaged to be married). With this relationship outlined in the film’s opening moments, the keen viewer will observe that convention dictates Jiro will eventually come to realise Matsuda’s positive qualities and, overcoming his prejudices, regard her as a suitable mate. Jiro is introduced in a wrestling gym whilst his admirer, Matsuda, watches on from her fencing class, which is taking place in the other half of the gymnasium. Their relationship is deftly sketched in the film’s opening sequences: Matsuda is in love with Jiro, though she stops just a little short of declaring this to him, whilst Jiro – who is slightly older – regards her as little more than a child (‘Of course, you’re still a kid to me’, he tells her when she reveals that she is engaged to be married). With this relationship outlined in the film’s opening moments, the keen viewer will observe that convention dictates Jiro will eventually come to realise Matsuda’s positive qualities and, overcoming his prejudices, regard her as a suitable mate.

Unlike the more gritty and moody monochrome film noir-esque Nikkatsu productions, Tokyo Mighty Guy foregrounds its sense of glossy Hollywood-style artifice from its opening titles sequence. The film begins with a titles sequence that features vibrant colour photography, sets and a strong dose of theatricality that could have come straight from a Hollywood musical of the 1950s. On a stage with a painted backdrop, the main characters perform a song and dance number for the film’s audience. The lyrics of the song foreground the theme of cultural hybridity that runs throughout the rest of the film’s narrative: ‘In Montmartre, I sang a chanson with a Ginza touch and captured the heart of a Parisian girl’, Jiro sings. Jiro’s family’s restaurant serves French food: Jiro’s family are known for ‘start[ing] that Western cuisine restaurant in Ginza’. The dastardly plan of the Asais is to acquire Matsuda’s family’s traditional Japanese bathhouse through Ryuzo’s marriage to Matsuda, before turning it into an ‘impure’ Turkish bathhouse. As the narrative progresses, the film nods to the conventions of Hollywood musicals whilst also taking the form of a bedroom farce for a good portion of its running time. The humour is often broad. For example, in an early scene Jiro is shown to be visiting the bathhouse owned by Matsuda’s family. He sings whilst bathing; this causes an argument amongst the women in the next room. Two middle-aged women begin to fight with one another. Matsuda calls on Jiro to stop the squabbling. He does so, but during the commotion the towel he has been wearing around his waist falls down. A montage ensues, intended to symbolise the shock of the women in the room: shocked faces are cut against shots of a clock whose hands are rapidly travelling backwards.  In the dialogue, Jiro allies himself with the edokko a number of times. These ‘children of Edo’ are usually represented in fiction as plucky, poor at making money but free in terms of their ability to spend it, proud and independent, and with a strong sense of community. Comparisons are often drawn between the stereotypes associated with the eddoko and those connected to how Cockney culture has been represented in films such as Mary Poppins (Robert Stevenson, 1964) (see Smith, 1979: 84). For Jiro, his eddoko spirit – defined by a sense of community – means that he is unable to resist helping someone who needs his assistance, even if it places him in trouble, and also ensures that he is unafraid of challenging those in authority (such as Ipponyari) whom Jiro believes to have done wrong. When Ipponyari’s car crashes into his family’s restaurant, Ipponyari attempts to pull rank with the police officer. ‘I’m not going to let you off’, Jiro asserts, ‘My edokko sould won’t be satisfied’. Jiro demands an apology, leaving Ipponyari incensed. However, later on, it is precisely this independence of spirit that causes Ipponyari to warm to Jiro. When the gangsters approach Jiro and offer to help him seek recompense from Ipponyari, Jiro demonstrates the same sense of independence, telling the yakuza, ‘I don’t need gangster help’. When the gangsters have left, Jiro tells his family, ‘I’ve gotten used to gangsters’. ‘There are gangsters in Paris too?’, Jiro’s less-than-worldly father asks in disbelief. In the dialogue, Jiro allies himself with the edokko a number of times. These ‘children of Edo’ are usually represented in fiction as plucky, poor at making money but free in terms of their ability to spend it, proud and independent, and with a strong sense of community. Comparisons are often drawn between the stereotypes associated with the eddoko and those connected to how Cockney culture has been represented in films such as Mary Poppins (Robert Stevenson, 1964) (see Smith, 1979: 84). For Jiro, his eddoko spirit – defined by a sense of community – means that he is unable to resist helping someone who needs his assistance, even if it places him in trouble, and also ensures that he is unafraid of challenging those in authority (such as Ipponyari) whom Jiro believes to have done wrong. When Ipponyari’s car crashes into his family’s restaurant, Ipponyari attempts to pull rank with the police officer. ‘I’m not going to let you off’, Jiro asserts, ‘My edokko sould won’t be satisfied’. Jiro demands an apology, leaving Ipponyari incensed. However, later on, it is precisely this independence of spirit that causes Ipponyari to warm to Jiro. When the gangsters approach Jiro and offer to help him seek recompense from Ipponyari, Jiro demonstrates the same sense of independence, telling the yakuza, ‘I don’t need gangster help’. When the gangsters have left, Jiro tells his family, ‘I’ve gotten used to gangsters’. ‘There are gangsters in Paris too?’, Jiro’s less-than-worldly father asks in disbelief.

In many ways, the film is about the conflicts between different classes and social mobility: Jiro’s real ‘problems’ begin when his encounter with the man who becomes his sponsor, Ipponyari, results in Ippoyata renovating Jiro’s family’s restaurant, turning their modest business into an establishment that is patronised by the likes of the French ambassador. Ipponyari and Jiro, representatives of the older and younger generations – the former a politician, the latter a member of the edokko - find themselves allied against the plotting of the middle-aged and middle-class Asais, suggesting that comradeship can transcend age and social standing whilst also highlighting the enemy in the middle. ‘I’ve heard that gangsters and businessemen have ties’, Jiro tells Asai when he confronts him at the climax of the picture, ‘but I didn’t know how close’.  Tokyo Mighty Guy meanders in the mid-section – there’s a sojourn to an island retreat which feels very much like a Japanese version of Carry on Camping (Gerald Thomas, 1969) – before heading to a climax which has strange parallels with Mike Nichols’ later The Graduate (1967). It’s a light-hearted, youth-oriented picture – unfocused but charming nonetheless, partly owing to its freewheeling approach to narrative. Tokyo Mighty Guy meanders in the mid-section – there’s a sojourn to an island retreat which feels very much like a Japanese version of Carry on Camping (Gerald Thomas, 1969) – before heading to a climax which has strange parallels with Mike Nichols’ later The Graduate (1967). It’s a light-hearted, youth-oriented picture – unfocused but charming nonetheless, partly owing to its freewheeling approach to narrative.

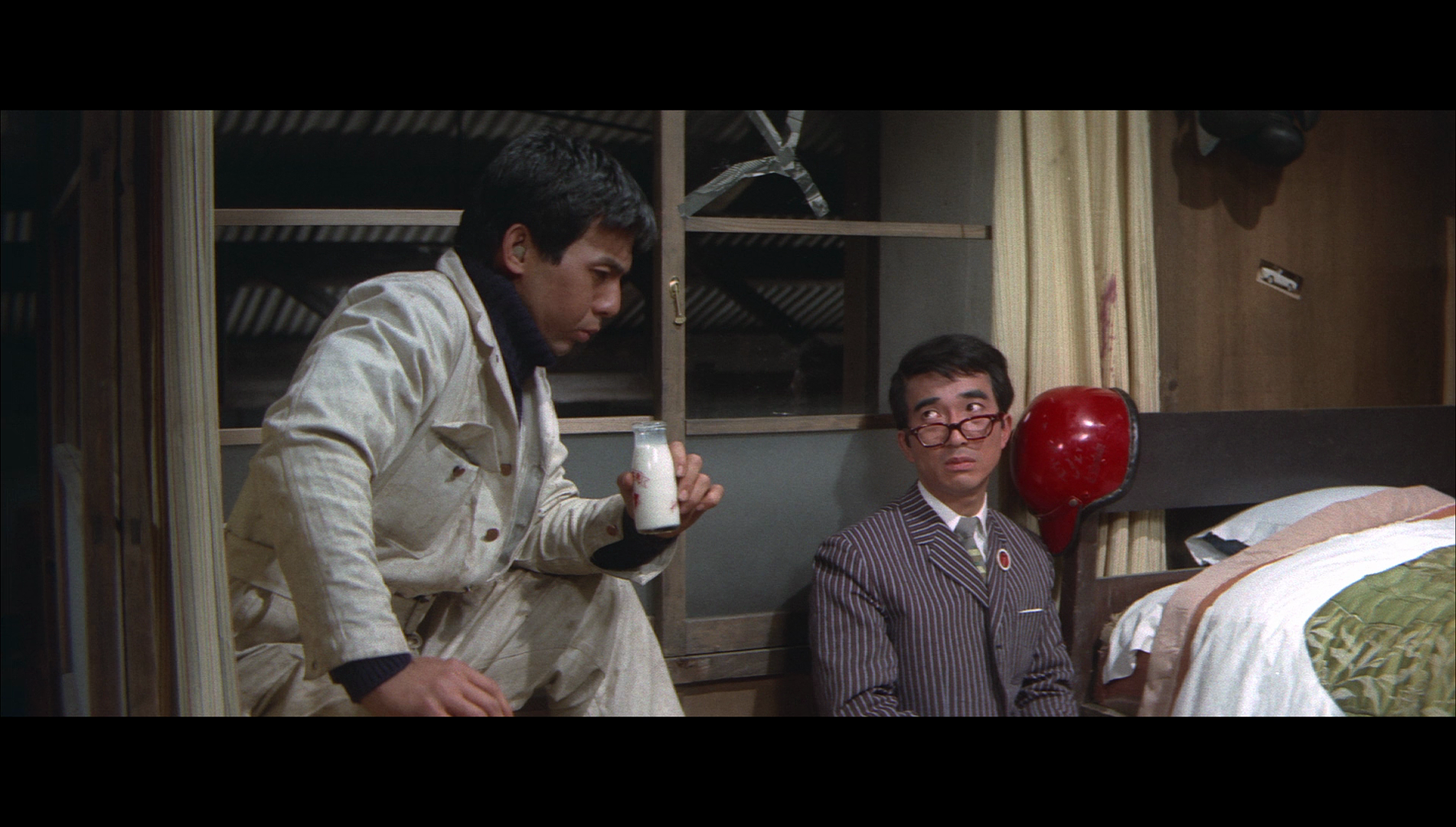

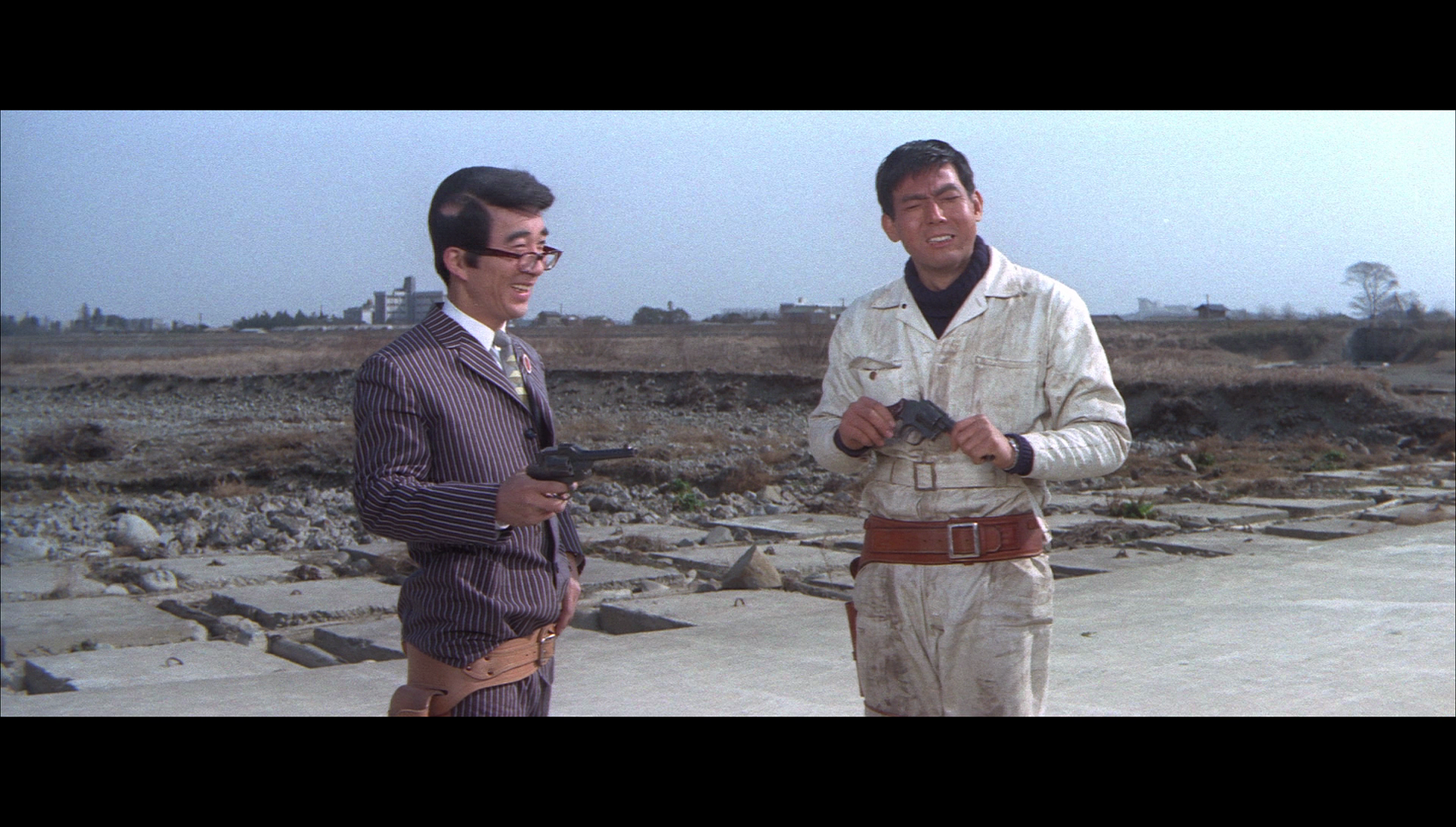

Danger Pays has previously been known by a slightly mangled and nonsensical English title, Danger Paws. The film begins with a daylight robbery: gangsters set upon the van of a courier, stealing watermarked papers worth over a billion yen. Finding his details in ‘Crime Weekly’, these gangsters hire the man billed as ‘Japan’s most skilled counterfeiter’. When this forger, Sakamoto (Hidari Bokuzen), arrives at the airport, he encounters ‘Glass Headed’ Joe (Shishido Jo). Joe is approached by ‘Slide-Rule’ Tetsu (Nagato Hiroyuki) and ‘Dump-Truck’ Ken (Kusanagi Kojiro), who have a proposition for him. As Sakamoto sets to work preparing to transform the watermarked papers into counterfeit money, the gangsters who have hired him become concerned that Slide-Rule, Dump-Truck and Joe are onto them and have recognised Sakamoto. With the assistance of Tomoko (Asaoka Ruriko), a secretary who is an expert in Judo and has a degree in French literature, Joe and the others decide to abduct Sakamoto. They trace his location to the Cabaret Acapulco, a nightclub owned by the gangsters. The stage is set for a conflict between Joe and his friends and the gangsters, with Sakamoto and his wife (Takechi Toyoko) caught in the middle.  Like the previous film, Tokyo Mighty Guy, Danger Pays foregrounds a theme of East meets West, in terms of the Cabaret Acapulco, the nightclub owned by the gangsters who have stolen the watermarked papers and hired the forger. As the film begins, a male voice is heard saying, ‘Confucius says: “A wise man never courts danger”. I would say: “Danger’s where the money is”’. With this assertion, the film’s thesis is sketched for the audience: a satirical exploration of crime as capitalist enterprise. (This theme links Danger Pays with Murder Unincorporated, the final feature in this set.) When the gangsters who have stolen the watermarked papers need to find a master forger with the skill to turn these papers into counterfeit money, they look in the pages of a publication named ‘Crime Weekly’ as if searching through the classified ads of their local newspaper. For his part, the forger sees himself as an artist of sorts: ‘The risk is high and the profit low’, he says about his talent, but ‘the work is like alchemy’. However, his stipulations about his work are bizarre. He demands to work in a room below the nightclub owned by the gangsters, the Cabaret Acapulco, where from his desk he may look up and observe the women performing their racy dances for the club’s audience. This gives the filmmakers an opportunity to include some prurient shots of one of the dancers in the nightclub performing the splits whilst the camera gazes up at her crotch through the glass dance floor, before the camera tilts down to reveal Sakamoto working at his desk, leering at the woman from below. It’s a scene that is probably meant to be amusing, whilst at the same time amplifying the male gaze, offering the male heterosexual audience a prurient glimpse of the female body without incorporating nudity and giving them the ‘excuse’ that they are simply sharing the gaze of Sakamoto; but, especially in the manner that it halts the narrative, it feels more sleazy than anything else and is very ‘out of place’ in relation to most of the other moments of humour in the film. A later joke about the Holocaust also feels slightly off-note. When the leader of the gangsters, Hijikata (Hamada Torahiko), locks Joe and his friends in a sealed room and begins to fill the room with gas, Slide-Rule declares, ‘This is a historical death. Like the Nazi gas chambers’. In response, Dump-Truck says ‘Hijikata is like Eichmann, damn it’. Like the previous film, Tokyo Mighty Guy, Danger Pays foregrounds a theme of East meets West, in terms of the Cabaret Acapulco, the nightclub owned by the gangsters who have stolen the watermarked papers and hired the forger. As the film begins, a male voice is heard saying, ‘Confucius says: “A wise man never courts danger”. I would say: “Danger’s where the money is”’. With this assertion, the film’s thesis is sketched for the audience: a satirical exploration of crime as capitalist enterprise. (This theme links Danger Pays with Murder Unincorporated, the final feature in this set.) When the gangsters who have stolen the watermarked papers need to find a master forger with the skill to turn these papers into counterfeit money, they look in the pages of a publication named ‘Crime Weekly’ as if searching through the classified ads of their local newspaper. For his part, the forger sees himself as an artist of sorts: ‘The risk is high and the profit low’, he says about his talent, but ‘the work is like alchemy’. However, his stipulations about his work are bizarre. He demands to work in a room below the nightclub owned by the gangsters, the Cabaret Acapulco, where from his desk he may look up and observe the women performing their racy dances for the club’s audience. This gives the filmmakers an opportunity to include some prurient shots of one of the dancers in the nightclub performing the splits whilst the camera gazes up at her crotch through the glass dance floor, before the camera tilts down to reveal Sakamoto working at his desk, leering at the woman from below. It’s a scene that is probably meant to be amusing, whilst at the same time amplifying the male gaze, offering the male heterosexual audience a prurient glimpse of the female body without incorporating nudity and giving them the ‘excuse’ that they are simply sharing the gaze of Sakamoto; but, especially in the manner that it halts the narrative, it feels more sleazy than anything else and is very ‘out of place’ in relation to most of the other moments of humour in the film. A later joke about the Holocaust also feels slightly off-note. When the leader of the gangsters, Hijikata (Hamada Torahiko), locks Joe and his friends in a sealed room and begins to fill the room with gas, Slide-Rule declares, ‘This is a historical death. Like the Nazi gas chambers’. In response, Dump-Truck says ‘Hijikata is like Eichmann, damn it’.

The film contains some abrupt shifts in tone. The lighter moments of humour jar with the opening sequence, which depicts the hold-up of the courier’s car carrying the watermarked papers. The two men traveling in this car are stabbed brutally, a close-up showing the knife entering the belly of one of the men and blood pouring out. It’s a shocking, violent sequence, especially for its time, and sets a tone that is in contrast with the film’s later emphasis on knockabout comedy. For the most part, the picture features rapid-fire comedy, with jokes – both slapstick and verbal – coming thick and fast. Despite the fact that for most audiences, he’s associated with hardboiled ‘tough guy’ roles, in this film Shishido Jo demonstrates how adept he is at physical comedy, gurning with delight when the script requires him to. In the sequence in which he is depicted arriving at the airport, Slide-Rule demonstrates why Joe is nicknamed ‘Glass-Headed’ Joe: because ‘the screeching sound of scratching glass’ make shim cringe and scream in terror. Slide-Rule proves this by making this sound, and Joe, who is walking away at the time, is briefly reduced to a shrieking, quivering wreck. Shishido was never as big a star as Kobayashi Akira, for whatever reason, but he was always a dependable screen presence, and he’s very likeable here. The film contains some abrupt shifts in tone. The lighter moments of humour jar with the opening sequence, which depicts the hold-up of the courier’s car carrying the watermarked papers. The two men traveling in this car are stabbed brutally, a close-up showing the knife entering the belly of one of the men and blood pouring out. It’s a shocking, violent sequence, especially for its time, and sets a tone that is in contrast with the film’s later emphasis on knockabout comedy. For the most part, the picture features rapid-fire comedy, with jokes – both slapstick and verbal – coming thick and fast. Despite the fact that for most audiences, he’s associated with hardboiled ‘tough guy’ roles, in this film Shishido Jo demonstrates how adept he is at physical comedy, gurning with delight when the script requires him to. In the sequence in which he is depicted arriving at the airport, Slide-Rule demonstrates why Joe is nicknamed ‘Glass-Headed’ Joe: because ‘the screeching sound of scratching glass’ make shim cringe and scream in terror. Slide-Rule proves this by making this sound, and Joe, who is walking away at the time, is briefly reduced to a shrieking, quivering wreck. Shishido was never as big a star as Kobayashi Akira, for whatever reason, but he was always a dependable screen presence, and he’s very likeable here.

The final film in this set, Murder Unincorporated, begins with the assassination of a gang leader, Yoyoki. His death leaves a void in the group of gangsters with which he is associated, who meet like the board of directors of an important company. When the remaining gang leaders – Kishida, Sakurada and Kumoi – receive a threatening telephone call from the mysterious ‘Joe of Spades’, they begin to fear for their own lives and decide to hire a team of assassins – the very best – to identify Joe of Spades and kill him before he can kill them. However, one of the assassins, Konmatsu, makes friends with a mysterious outsider (Shishido Jo).  The narrative is punctuated by flashbacks and extended flights of fantasy. After the group of gangsters receive the call from Joe of Spades, Kumoi experiences a flashback to twenty years earlier, believing that Joe may be the son of a man he hijacked during his youth. Later, Konmatsu tells Shishido Jo’s character of his plans to save two million yen which will allow him to achieve his dream of buying a drug store and selling a hair growth formula for those who are, like him, follicly challenged. This leads to an extended flashback in which the younger Konmatsu is shown working in a drug store, where he is bullied by the owner. The narrative is punctuated by flashbacks and extended flights of fantasy. After the group of gangsters receive the call from Joe of Spades, Kumoi experiences a flashback to twenty years earlier, believing that Joe may be the son of a man he hijacked during his youth. Later, Konmatsu tells Shishido Jo’s character of his plans to save two million yen which will allow him to achieve his dream of buying a drug store and selling a hair growth formula for those who are, like him, follicly challenged. This leads to an extended flashback in which the younger Konmatsu is shown working in a drug store, where he is bullied by the owner.

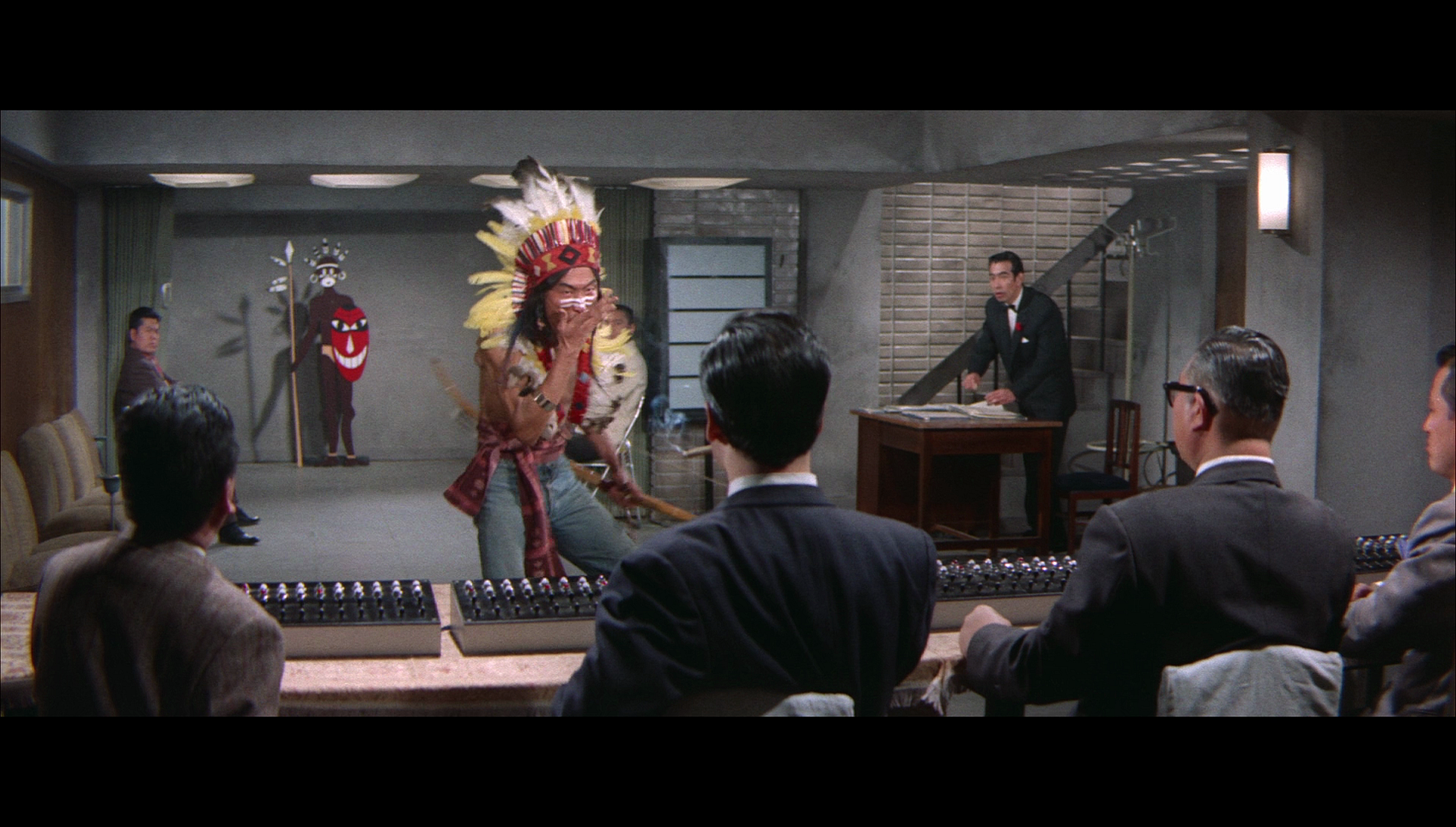

From the get-go, this film offers a parodic Pop Art world whose closest corollary is perhaps The Man from UNCLE (1964-8), the 1967 Casino Royale or the roughly contemporaneous Matt Helm pictures which starred Dean Martin (for example, Henry Levin’s Murderers’ Row, 1966). In fact, it’s easy to imagine John Frankenheimer watching this before making his satirical Pop Art gangster picture 99 & 44/100% Dead (1974). The film begins with an iris effect, most likely intended as a parody of the famous gunbarrel openings of the then-in-vogue James Bond pictures. In the middle of this, a man points at the camera, addressing the audience directly: ‘If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you’, he threatens. This cuts abruptly to a close-up shot of a gun firing. The film’s focus on comedy juxtaposed with action is thus established immediately, as is the satirical examination of male authority. Following this opening sequence, the film presents the audience with some documentary-style travelogue stock footage of Tokyo as a narrator tells us about Japan’s urban environments, before taking us to a small town that the narrator describes as a ‘killer town’ owing to its association with criminality and violence.  The gang headed by the group of middle-aged men to whom Yoyoki belongs controls 95% of the profits in this town. The men run their criminal enterprise like a business, meeting like a board of directors. When they decided to hire a team of assassins to protect them, after receiving the threatening telephone call from Joe of Spades, they call a hotline and speak to a severe woman who takes their queries like a telesales operator. She arranges an ‘audition’, sending a large number of potential assassins to the men; these assassins all gather at an ‘Assassins Examination Room’ where they are tested for their compatibility for the task at hand. They are expected to ‘perform’ for the group of gangsters who plan to hire them, before being ranked and selected. The gang headed by the group of middle-aged men to whom Yoyoki belongs controls 95% of the profits in this town. The men run their criminal enterprise like a business, meeting like a board of directors. When they decided to hire a team of assassins to protect them, after receiving the threatening telephone call from Joe of Spades, they call a hotline and speak to a severe woman who takes their queries like a telesales operator. She arranges an ‘audition’, sending a large number of potential assassins to the men; these assassins all gather at an ‘Assassins Examination Room’ where they are tested for their compatibility for the task at hand. They are expected to ‘perform’ for the group of gangsters who plan to hire them, before being ranked and selected.

Here, murder is depicted as the ultimate form of capitalist enterprise, via the film’s focus on a secret network of killers-for-hire: ordering a hired killer is as simple as picking up the telephone to order some stationery for the office. Whether these assassins are hired or not depends on how well they perform in their ‘interview’. As if to hammer this point home, the film even contains a scene in which one of the assassins asks about the company benefits associated with the position. The final group of assassins are made up of various cultural stereotypes: a poet who carries a book of poetry that, when opened to page thirteen, fires a bullet out of its spine; a cowboy; a James Bond clone (‘006, the boss of 007’) whose briefcase fires grenades (a couple of years after the gadget-laden attaché case that featured in the film adaptation of From Russia With Love, 1963). The media savvy approach is delineated in a scene that takes place after three of the assassins have been murdered. Suspicious of the remaining assassins, one of the gangsters asks an assassin, ‘Where were you last night?’ ‘I was watching television’, the assassin replies, ‘The Untouchables. It’s possible that Joe [of Spades] might be in the show’.

Video

The three films are housed on the same Blu-ray disc. Tokyo Mighty Guy takes up approximately 15Gb of space on this disc, and the other two pictures take up a little over 13Gb each. All of the films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The three films are housed on the same Blu-ray disc. Tokyo Mighty Guy takes up approximately 15Gb of space on this disc, and the other two pictures take up a little over 13Gb each. All of the films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

Tokyo Mighty Guy has a running time of 78:46 mins; Danger Pays runs for 82:02 mins; Murder Unincorporated runs for 84:53 mins. The presentations of all three films are pretty similar. All three pictures are presented in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio. The films display the characteristics of many Japanese films shot anamorphically during the 1960s: the anamorphic lenses used to shoot these films, especially in low light scenes where the lenses would have been used wide open, display a softness at the periphery of the frame whilst the centre of the image is often very sharp. All three films, again like many Japanese pictures shot anamorphically during the 1960s, tend to favour short focal lengths to emphasise the sense of space within often fairly confined sets and to also establish a strong depth of field even in interior low light scenes, and the barrel distortion that’s present in many shots is obviously a characteristic of these lenses with shorter focal lengths. Aspects of the original photography aside, Arrow’s presentations of all three films are uniformly good. A strong level of detail is present throughout, with nicely balanced contrast characterised by strong mid-tones and excellent colour reproduction. For example, in Tokyo Mighty Guy, there are a number of shots featuring the camera at a low-angle looking up at the characters with the deep blue sky framing their faces. This is an awkward lighting situation for the film’s original photography to handle, without either blowing out the background or obscuring the details in the foreground in shadow. It’s the kind of image that wouldn’t have fared terribly well on the DVD format owing to the impact of the compression of standard definition digital video on the contrast within the image. By contrast (pun intended), this HD presentation shows how carefully balanced the exposure within the original photography was, with neither the rich blue of the sky nor the foreground details sacrificed at the expense of the other. The use of shorter focal lengths results in a strong sense of depth within the original photography, which is replicated here owing to the superb level of detail within these HD presentations. Finally, all three presentations retain the structure of 35mm film – or as close to it as a digital simulacrum will allow. Tokyo Mighty Guy:

Danger Pays:

Murder Unincorporated:

Audio

All three films are presented in Japanese via LPCM 1.0 tracks, with accompanying optional English subtitles. In the case of all three films, the audio tracks are superb and demonstrate excellent range. They are clear throughout. It’s worth mentioning that a few short scenes in Tokyo Mighty Guy are in French with burnt-in Japanese subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Introduction to the Diamond Guys: Shishido Jo (9:15) and Kobayashi Akira (11:06). In these two short featurettes, Jasper Sharp reflects on the careers of Shishido and Kobayashi, discussing their work from their first appearances in Nikkatsu productions. Sharp gives all three films presented here a strong sense of context, and his comments are insightful and well-researched. - Trailers: Tokyo Mighty Guy (3:47); Danger Pays (3:51); Murder Unincorporated (4:11). - Galleries: Tokyo Mighty Guy (0:25); Danger Pays (0:27); Murder Unincorporated (0:17). - Outlaw Gangster VIP Collection Trailers: Gangster VIP (3:09); Gangster VIP 2 (2:35); Heartless (2:35); Goro the Assassin (2:57); Black Dagger (2:59); Kill (3:15). Retail copies also include on of Arrow’s superb booklets. This one includes credits for all three films and articles about each picture. Tom Mes writes about Tokyo Mighty Guy in a piece entitled ‘Aiming High with the Tokyo Mighty Guy’; March Schilling writes about Danger Pays in ‘Danger’s Where the Money Is’; and Stuart Galbraith IV writes about Murder Unincorporated in ‘Comedy Unincorporated’.

Overall

Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guy sets represent excellent value for money. All three films here are linked by a strong focus on comedy and artifice, which sets them apart from some of the more moody film noir style productions Nikkatsu made at around the same time (the mid-1960s). There’s a youth oriented comedy drama (Tokyo Mighty Guy), a light-hearted caper movie (Danger Pays) and a Pop Art underworld spoof (Murder Unincorporated). All three films to some extent deal with themes of cultural hybridity, which is a theme that often crops up in Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless’ pictures. There are some interesting points of comparison with Western films (for example, in the similarities between Tokyo Mighty Guy’s climax and that of The Graduate): the latter two films, in particular, perhaps find their closest corollary in films such as Carry on Spying (Gerald Thomas, 1964) and The Intelligence Men (Robert Asher, 1965), whilst Tokyo Mighty Guy is a youth picture very much in the Elvis Presley/Cliff Richard mould. In all, containing excellent presentations of the three pictures and some good contextual material in the form of the interviews with Jasper Sharp about Shishido and Kobayashi, this is a very good release, and hopefully we will see Arrow release more of these films in the future. Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guy sets represent excellent value for money. All three films here are linked by a strong focus on comedy and artifice, which sets them apart from some of the more moody film noir style productions Nikkatsu made at around the same time (the mid-1960s). There’s a youth oriented comedy drama (Tokyo Mighty Guy), a light-hearted caper movie (Danger Pays) and a Pop Art underworld spoof (Murder Unincorporated). All three films to some extent deal with themes of cultural hybridity, which is a theme that often crops up in Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless’ pictures. There are some interesting points of comparison with Western films (for example, in the similarities between Tokyo Mighty Guy’s climax and that of The Graduate): the latter two films, in particular, perhaps find their closest corollary in films such as Carry on Spying (Gerald Thomas, 1964) and The Intelligence Men (Robert Asher, 1965), whilst Tokyo Mighty Guy is a youth picture very much in the Elvis Presley/Cliff Richard mould. In all, containing excellent presentations of the three pictures and some good contextual material in the form of the interviews with Jasper Sharp about Shishido and Kobayashi, this is a very good release, and hopefully we will see Arrow release more of these films in the future.

References: Smith, Henry D II, 1979: Tokyo and London: Comparing Conceptions of the City’. In: Craig, Albert M (ed), 1979: Japan: A Comparative View. Princeton University Press:49-104 Tokyo Mighty Guy

Danger Pays

Murder Unincorporated

|

|||||

|