|

|

Count Yorga, Vampire AKA The Loves of Count Iorga, Vampire (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (2nd August 2016). |

|

The Film

The Count Yorga Collection The Count Yorga Collection

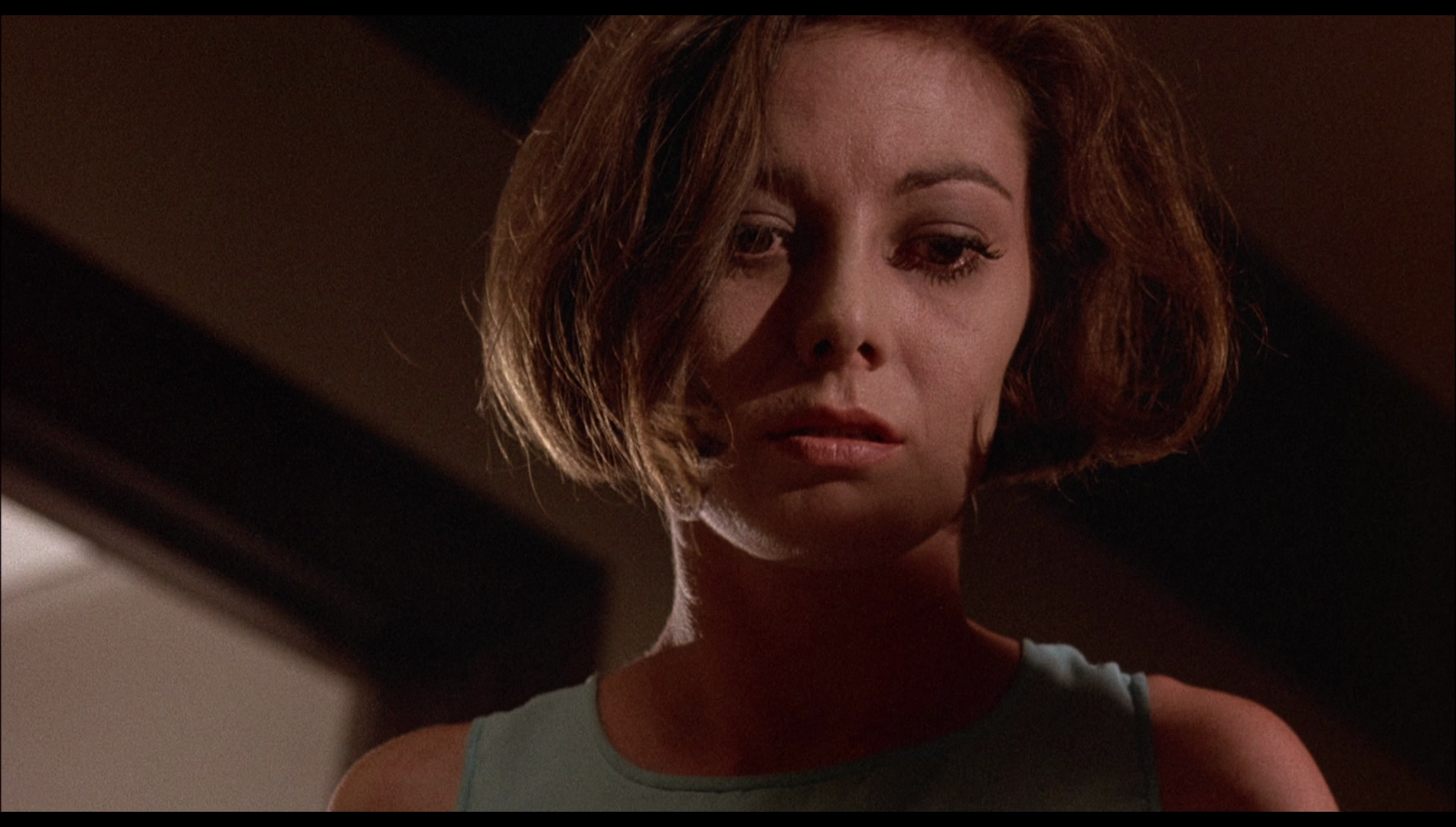

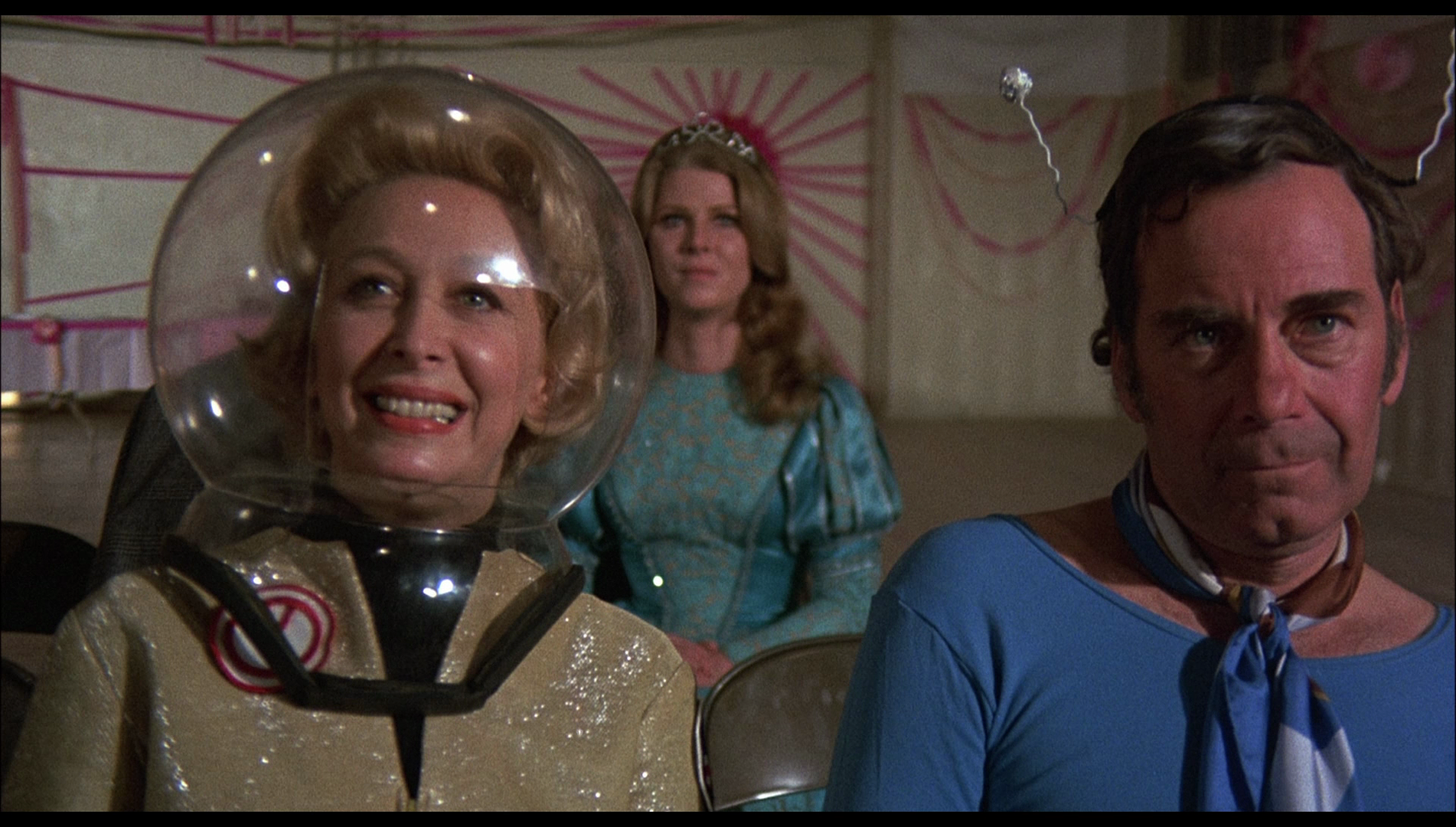

In the early 1970s, AIP distributed four films that brought vampires into the present day: Count Yorga, Vampire (1970), The Return of Count Yorga (1971), Blacula (William Crain, 1972) and Scream, Blacula, Scream (1973). Three of these films (Count Yorga, Vampire; The Return of Count Yorga; and Scream, Blacula, Scream) featured the involvement of the same director, Bob Kelljan. The Count Yorga pictures featured Robert Quarry as a vampire firmly in the tradition of Bela Lugosi’s portrayal of Bram Stoker’s Dracula; the Blacula pictures featured a more striking paradigmatic shift, casting the African American actor William Marshall as their lead vampire, the African Prince Mamuwalde, turned into a vampire by Dracula himself. Count Yorga, Vampire begins with a séance in the home of Donna (Donna Anders). Donna has commissioned her deceased mother’s lover, Yorga (Robert Quarry), to conduct the séance with the intention of communicating with her much-missed parent. At the séance are a number of Donna’s friends, including Erica (Judy Lang), Paul (Michael Murphy) and Mike (Michael Macready). Unbeknownst to the others, Donna is under the control of Yorga, and he is able to communicate with her telepathically. Following the séance, the group return to their respective homes. Paul and Erica offer to drive Yorga to his secluded country house. They are greeted at the gate by Brudah (Edward Walsh), Yorga’s brutish manservant. Leaving the grounds of Yorga’s house, Paul and Erica find their camper van stuck in some mud which has appeared mysteriously. They decide to spend the night in the van but are attached at night by Yorga, in his form as a vampire. They return to the city but remember nothing about the incident, although Erica bears the scars of the attack in the form of two mysterious bite marks on her neck. Dr Jim Hayes (Roger Perry) investigates these bite marks. In consultation with a colleague, he reaches the startling conclusion that Erica may in fact have encountered a vampire. However, he struggles to persuade the others of the veracity of his claim. Meanwhile, Erica is visited at night by Yorga, who is intent on making the beautiful young woman one of his brides. Eventually, Erica disappears, having been abducted by Yorga. Having persuaded Paul and Mike that Yorga may be a vampire and that the clue to saving Erica lies in killing him, Hayes stages an assault on Yorga’s home. However, those involved must combat not only Yorga but also the incredibly strong Brudah and Yorga’s vampire brides.  The Return of Count Yorga opens as an orphanage headed by Reverend Thomas (Tom Toner) holds a fund-raising fancy dress ball. One of the workers at the orphanage, Cynthia Nelson (Mariette Hartley), comments that she hears the Santa Ana winds, which are supposed to herald unfortunate events. In an old graveyard outside the building, one of the charges, Tommy (Philip Frame), plays with a football; but the earth cracks open and the vampire brides of Yorga rise from their graves, pursuing Tommy – who flees straight into the arms of Yorga. The Return of Count Yorga opens as an orphanage headed by Reverend Thomas (Tom Toner) holds a fund-raising fancy dress ball. One of the workers at the orphanage, Cynthia Nelson (Mariette Hartley), comments that she hears the Santa Ana winds, which are supposed to herald unfortunate events. In an old graveyard outside the building, one of the charges, Tommy (Philip Frame), plays with a football; but the earth cracks open and the vampire brides of Yorga rise from their graves, pursuing Tommy – who flees straight into the arms of Yorga.

When one of the young women at the party, Mitzi (Jesse Welles) disappears, psychiatrist David Baldwin (Roger Perry) attempts to track her down. Mitzi is discovered with bite marks on her throat. At Cynthia’s family home, the Santa Ana winds continue to disturb her, her father Bill (Walter Brooke), mother Marcia and sister Ellen (Karen Houston). Cynthia has invited Tommy, who claims to be frightened of the winds, to spend the night with her family, unaware that Tommy is actually under the spell of Yorga. During the night, Yorga’s corpselike brides attack the family, the violence of the women leaving the home in disarray. The only witness is Jennifer Nelson (Yvonne Wilder), who is mute. Jennifer attempts to persuade the police of the violence that took place in the Nelson house, but Tommy suggests she is lying and the Nelsons simply left their home peacefully. Meanwhile, Yorga has abducted Cynthia and taken her to his home, hypnotising her and convincing her that she was involved in a car accident, and that he took her in so as to allow her to recuperate. David and Jason (David Lampson), the boyfriend of Ellen, believe something more suspicious has happened and contact the eccentric Professor Rightstadt (George Macready), an expert in vampires. However, Cynthia begins to experience flashbacks (drenched expressionistically in red light) to the massacre of her family.  Count Yorga, Vampire was shot under the title The Loves of Count Yorga and was originally intended to be, at least in part, a softcore sex picture. The sex and nudity was dropped from the film when it went into production but the original title remained; since the 1990s, many releases of the film, including this new Blu-ray presentation, have carried onscreen the Loves of Count Yorga title, though the film is still known and promoted as Count Yorga, Vampire. According to Robert Quarry, Kelljan and the film’s writer Michael Macready, whom Quarry met through a theatre group with which he worked, approached him to make The Loves of Count Yorga. They wanted to make a ‘nudie’ picture because they thought it was a ‘sure sell’ (Quarry, in Sullivan, 2004: np). However, Quarry persuaded them that horror films were equally a ‘sure sell’. During production, they compromised by shooting the picture as a ‘straight’ horror film but also filming softcore scenes and some scenes of nudity that could be edited into the film with the intention of marketing it as a ‘nudie’ picture: ‘That is why there are so many random female characters such as the nurse and the secretary’ (Quarry, quoted in ibid.). When completed, it was decided that the version of the picture sans the nudity worked the best, and the softcore scenes were left out of the film. Though the completed film shies away from depicting sex and sexuality in an overly direct manner, one sequence in particular seems to feature a hangover from the original intentions for the picture: awaiting Yorga’s nighttime visit, clad in her revealing nightdress, Erica massages her breasts in anticipation of the arrival of the vampire. (Late in the film, when Brudah chases and captures Donna in a field, he throws her to the floor and the filmmakers put us in Donna’s position by cutting to an out-of-focus close-up of Brudah’s face as he looms over her; the implication that he has sexually assaulted her is indirect but confirmed later when Brudah begs for the count’s forgiveness for an undisclosed offence.) Count Yorga, Vampire was shot under the title The Loves of Count Yorga and was originally intended to be, at least in part, a softcore sex picture. The sex and nudity was dropped from the film when it went into production but the original title remained; since the 1990s, many releases of the film, including this new Blu-ray presentation, have carried onscreen the Loves of Count Yorga title, though the film is still known and promoted as Count Yorga, Vampire. According to Robert Quarry, Kelljan and the film’s writer Michael Macready, whom Quarry met through a theatre group with which he worked, approached him to make The Loves of Count Yorga. They wanted to make a ‘nudie’ picture because they thought it was a ‘sure sell’ (Quarry, in Sullivan, 2004: np). However, Quarry persuaded them that horror films were equally a ‘sure sell’. During production, they compromised by shooting the picture as a ‘straight’ horror film but also filming softcore scenes and some scenes of nudity that could be edited into the film with the intention of marketing it as a ‘nudie’ picture: ‘That is why there are so many random female characters such as the nurse and the secretary’ (Quarry, quoted in ibid.). When completed, it was decided that the version of the picture sans the nudity worked the best, and the softcore scenes were left out of the film. Though the completed film shies away from depicting sex and sexuality in an overly direct manner, one sequence in particular seems to feature a hangover from the original intentions for the picture: awaiting Yorga’s nighttime visit, clad in her revealing nightdress, Erica massages her breasts in anticipation of the arrival of the vampire. (Late in the film, when Brudah chases and captures Donna in a field, he throws her to the floor and the filmmakers put us in Donna’s position by cutting to an out-of-focus close-up of Brudah’s face as he looms over her; the implication that he has sexually assaulted her is indirect but confirmed later when Brudah begs for the count’s forgiveness for an undisclosed offence.)

Early in the second film, Yorga engages in a dialogue with Cynthia about the notion of purity. He expresses cynicism towards the concept at first, Cynthia telling him that the orphanage is ‘as close to purity as I can get’. ‘Purity of what?’, Yorga asks her. ‘Love; life’, she responds. ‘That matters to you?’, he queries. ‘Yes, very much so’, she tells him. ‘Unfortunately, I find it difficult to evaluate life and love on the basis of purity’, Yorga tells her, ‘However, truth… Cold, unemotional truth. One’s loss of innocence holds it’. As the narrative progresses, it seems that Yorga is, or becomes, almost pathologically obsessed with innocence; seeing this in Cynthia, he decides that he must make her his bride. However, he prevents himself from ‘turning’ her, maintaining her crystalline beauty in comparison with the corpse-like, ghoulish revenants who are his vampire brides. One of the female vampires within Yorga’s house warns him that his obsession with Cynthia will come to nought: ‘You’re a fool’, the woman says, ‘When she [Cynthia] discovers what you are, she will sicken at your nature. She will loathe you. Kill her. If you do no, you may not see another moon’. Later, Yorga confesses to Cynthia that she has caused the ‘most fragile emotion ever known [to enter] my life […] It will surely threaten my ability to survive’. He continues to say, ‘You, Cynthia, have brought me a gentle pain which I can only define as “love”. Can you love me [….] I could destroy you or turn you into the living dead, or let you go’. Early in the second film, Yorga engages in a dialogue with Cynthia about the notion of purity. He expresses cynicism towards the concept at first, Cynthia telling him that the orphanage is ‘as close to purity as I can get’. ‘Purity of what?’, Yorga asks her. ‘Love; life’, she responds. ‘That matters to you?’, he queries. ‘Yes, very much so’, she tells him. ‘Unfortunately, I find it difficult to evaluate life and love on the basis of purity’, Yorga tells her, ‘However, truth… Cold, unemotional truth. One’s loss of innocence holds it’. As the narrative progresses, it seems that Yorga is, or becomes, almost pathologically obsessed with innocence; seeing this in Cynthia, he decides that he must make her his bride. However, he prevents himself from ‘turning’ her, maintaining her crystalline beauty in comparison with the corpse-like, ghoulish revenants who are his vampire brides. One of the female vampires within Yorga’s house warns him that his obsession with Cynthia will come to nought: ‘You’re a fool’, the woman says, ‘When she [Cynthia] discovers what you are, she will sicken at your nature. She will loathe you. Kill her. If you do no, you may not see another moon’. Later, Yorga confesses to Cynthia that she has caused the ‘most fragile emotion ever known [to enter] my life […] It will surely threaten my ability to survive’. He continues to say, ‘You, Cynthia, have brought me a gentle pain which I can only define as “love”. Can you love me [….] I could destroy you or turn you into the living dead, or let you go’.

The appearance of Quarry’s vampire is very clearly styled on the iconic costume first used on screen by Bela Lugosi in Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), marrying this with the physicality of Christopher Lee’s incarnation of Dracula in the 1958 Hammer picture directed by Terence Fisher. Like Lee’s Dracula, Count Yorga has a physical vitality that was lacking in Lugosi’s portrayal of the vampire, and is able to run after his victims. In fact, the similarity of Yorga’s appearance to the iconic costume featured in Browning’s Dracula is a source of humour in the opening reel of The Return of Count Yorga. Whilst the orphanage is holding its fundraising fancy dress party, Yorga arrives for the first time. Also at the party is an elderly man who is dressed as Dracula, complete with white face makeup and fake fangs. When Yorga arrives, one of the other guests sees him and comments, ‘Oh, another vampire! Where are your fangs?’ ‘Where are your manners?’, Yorga asks in return. At the end of the sequence, the other partygoer wins the fancy dress costume, an example of the simulacrum (the Hollywood image of the vampire) seeming to be more familiar through repetition than the authentic (the ‘real’ vampire, Yorga).  Both films feature shots in which Yorga, filmed head-on, charges towards his victims with his arms outstretched, his fangs bared and a dreadful, predatory hiss on the soundtrack: in each film, these shots are presented, for emphasis, either via freeze frames or slow-motion, which makes the advance of the vampire seem all the more inevitable and deadly. (Perhaps the intention of this is to counteract the fact that, by 1972, the Lugosi-style vampire with its aristocratic dress had become an unthreatening cliché.) Where Tod Browning’s Dracula famously established Dracula’s ‘foreignness’ via the use of Lugosi’s strong Hungarian accent, thus identifying the vampire as a foreign invader, the Count Yorga pictures reinforce Yorga’s identity as a foreigner not by an accent but by Yorga’s dress and references within the dialogue to Yorga’s status as an immigrant to America from Bulgaria. The opening sequence features a series of documentary-like shots, filmed with long lenses which give a sense of documentary-style verisimilitude to the proceedings, which show cargo being unloaded from a ship and transported to their destination via truck; the cargo, we presume, is Yorga himself, arriving in America in a similar manner to which Dracula arrived in Whitby via wooden boxes aboard the Russian schooner Demeter. (There’s a similar sequence in Blacula, but in that picture the comparable sequence takes place after a sequence showing Mamuwalde’s origins in Europe.) Both films feature shots in which Yorga, filmed head-on, charges towards his victims with his arms outstretched, his fangs bared and a dreadful, predatory hiss on the soundtrack: in each film, these shots are presented, for emphasis, either via freeze frames or slow-motion, which makes the advance of the vampire seem all the more inevitable and deadly. (Perhaps the intention of this is to counteract the fact that, by 1972, the Lugosi-style vampire with its aristocratic dress had become an unthreatening cliché.) Where Tod Browning’s Dracula famously established Dracula’s ‘foreignness’ via the use of Lugosi’s strong Hungarian accent, thus identifying the vampire as a foreign invader, the Count Yorga pictures reinforce Yorga’s identity as a foreigner not by an accent but by Yorga’s dress and references within the dialogue to Yorga’s status as an immigrant to America from Bulgaria. The opening sequence features a series of documentary-like shots, filmed with long lenses which give a sense of documentary-style verisimilitude to the proceedings, which show cargo being unloaded from a ship and transported to their destination via truck; the cargo, we presume, is Yorga himself, arriving in America in a similar manner to which Dracula arrived in Whitby via wooden boxes aboard the Russian schooner Demeter. (There’s a similar sequence in Blacula, but in that picture the comparable sequence takes place after a sequence showing Mamuwalde’s origins in Europe.)

Over the opening shots of Count Yorga, Vampire, we are presented with voiceover narration which attempts to explain some elements of vampire lore for the audience. The narrator tells us that ‘A vampire, in ancient belief, was a malignant spirit who, when the Earth lost its own light, rose nightly from his dark grave to suck blood from the throats of the living’. The narrator tells us of some of the lore associated with vampires and the methods used to dispel them. The combination of this voiceover narration and the documentary-like shots of Yorga’s coffin traveling along America’s roads gives the whole sequence the feel of a newsreel. The narrator concludes his voiceover by foregrounding for the viewer one of the main selling points of the Yorga pictures, which differentiated them from the Hammer vampire films and their imitators: the setting in modern America. ‘I seem to be making use of the past tense, but perhaps the present is more precise’, the narrator intones, ‘For it stands to reason that if one is superstitious, even on a seemingly insignificant level, one must be vulnerable to all superstitions – conceivable, even those of vampires’.  Both films make much of the conflict between the superstition (represented via a belief in vampires) and the rationality of the modern world, with the characters struggling to convince others that vampires exist and are a significant threat. Some humour is built around this too: when Hayes first inspects Erica, finding the strange bite marks on her neck, he believes she is suffering from a form of anaemia and tells her to eat steaks – ‘the rawer, the better’. Shortly afterwards, Paul and Mike return to Erica’s home and discover her eating a dead, raw, kitten, its lifeless body in her hands and its blood smeared around her mouth. Hayes also tries to cure Erica via a blood transfusion (recalling the blood transfusion scene in Terence Fisher’s Dracula). When Hayes attempts to suggest to Paul and Mike that Yorga may in fact be a vampire, he is naturally reticent to do so, and they are deeply skeptical. However, he tries to reason with them: ‘Can you say that vampires do not exist? Can you state unequivocally that all those horror stories we read as children were merely superstitious horror tales and not fact?’ Both films make much of the conflict between the superstition (represented via a belief in vampires) and the rationality of the modern world, with the characters struggling to convince others that vampires exist and are a significant threat. Some humour is built around this too: when Hayes first inspects Erica, finding the strange bite marks on her neck, he believes she is suffering from a form of anaemia and tells her to eat steaks – ‘the rawer, the better’. Shortly afterwards, Paul and Mike return to Erica’s home and discover her eating a dead, raw, kitten, its lifeless body in her hands and its blood smeared around her mouth. Hayes also tries to cure Erica via a blood transfusion (recalling the blood transfusion scene in Terence Fisher’s Dracula). When Hayes attempts to suggest to Paul and Mike that Yorga may in fact be a vampire, he is naturally reticent to do so, and they are deeply skeptical. However, he tries to reason with them: ‘Can you say that vampires do not exist? Can you state unequivocally that all those horror stories we read as children were merely superstitious horror tales and not fact?’

When other crimes seem to bear the hallmarks of attacks by vampires – including reports of a dead baby found in a swamp, its body exsanguinated and ‘his neck all chewed up’ – Hayes telephones the police station and attempts to persuade the officer on the other end of the line that a vampire may be responsible for these crimes. The police officer, of course, mocks Hayes. After putting down the telephone, Hayes turns to his lover Cleo (Julie Conners) and, reiterating the words that the police officer said to him, declares, ‘I am the forty-seventh nut to call the police and say that a vampire exists, and I should be ashamed of myself for having such a sick, morbid sense of humour’. Hayes concludes that he must dispatch the vampire himself, seeking the help of Mike and Paul to do so. Having persuaded Mike and Paul that Yorga may indeed be a vampire, however, he finds another struggle in persuading them to conspire to execute the vampire. ‘How do you feel about driving a wooden stake into somebody’s heart?’, Hayes asks Mike. ‘Marvelous’, Mike responds. ‘That’s good, because I think you and I are going to have to kill Count Yorga’, Hayes declares. ‘You’re out of your mind’, Mike asserts in astonishment. ‘There won’t be any proof’, Hayes reasons before adding, unconvincingly, ‘His body will turn to ashes’. Upping the ante, Hayes then suggests that ‘It’s possible Paul and Erica may have turned into vampires. If that’s true, we’ll have to kill them too’. Preparing to storm Yorga’s country house, Hayes and Mike are shown breaking furniture and using the wood to make makeshift crosses. ‘Ridiculous, right?’, Hayes says, ‘The age of atomic weapons and we have to use sticks’.  In The Return of Count Yorga, the opening fancy dress party sequence leads to a discussion of vampires, with Yorga questioning how the other characters cannot believe in vampires. ‘Why do you discount the possibility of the classical vampire?’, he asks them. ‘Come on, even to consider it is absurd’, one of the partygoers responds. ‘Twentieth Century. Man on the moon, remember’, another says. Yorga continues to try to impress upon David the veracity of stories about vampires, however: ‘Mr Baldwin, I suggest you seriously anticipate the possibility of anything’, Yorga asserts, ‘One never knows when one may encounter the more… unusual truths that exist in our world’. In The Return of Count Yorga, the opening fancy dress party sequence leads to a discussion of vampires, with Yorga questioning how the other characters cannot believe in vampires. ‘Why do you discount the possibility of the classical vampire?’, he asks them. ‘Come on, even to consider it is absurd’, one of the partygoers responds. ‘Twentieth Century. Man on the moon, remember’, another says. Yorga continues to try to impress upon David the veracity of stories about vampires, however: ‘Mr Baldwin, I suggest you seriously anticipate the possibility of anything’, Yorga asserts, ‘One never knows when one may encounter the more… unusual truths that exist in our world’.

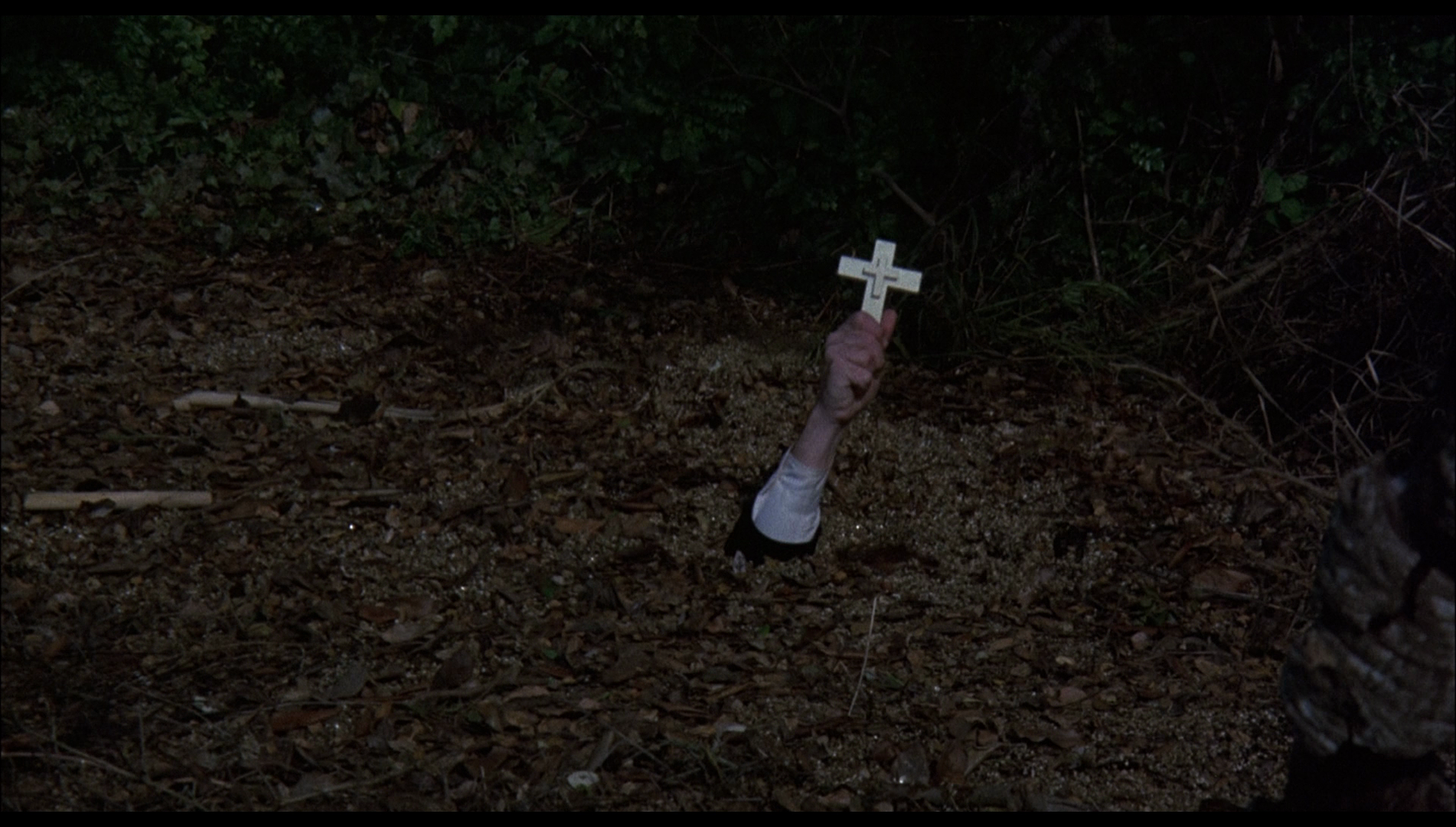

The modern day setting was, supposedly, introduced as a way of dealing with the fact that the production didn’t have enough funds to establish a convincing period setting – though this is precisely the feature that differentiates this film from, for example, the likes of Hammer’s vampire films. (Notably, when Hammer did attempt to bring their vampire tales into the present day, with Dracula A.D. 1972, directed by Alan Gibson in 1972, the result was a picture that is almost unanimously considered to be a disaster.) In fact, in what seems like an attempt to acknowledge the differences between the Yorga films and Hammer’s period Gothics, at one point in The Return of Count Yorga, Yorga watches a period-set Hammer vampire film, The Vampire Lovers (Roy Ward Baker, 1970), via a television broadcast dubbed into Spanish. However, a similar modern day setting to the Yorga pictures had featured in two earlier independent American vampire films: H G Lewis’s A Taste of Blood (1967), set in Miami, and Andy Milligan’s shot-in-England vampire picture The Body Beneath (1970). In the second Yorga picture, the scenes of Yorga’s partially-decayed ‘brides’ descending upon their victims, Cynthia’s family, within their own home brings to mind in what seems to be a deliberate cultural allusion to the female participants (Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Kenwinkel) in the Tate-La Bianca murders but also, in terms of the specific iconography used in this sequence (the decaying faces of the women crowding around the camera), bears striking similarities to the vampire attacks in the aforementioned Milligan picture. A later film starring Quarry as a vampire, Deathmaster (Ray Danton, 1972), made even more bold parallels between vampire lore and the Manson cult, with Quarry’s vampire Khorda taking over a hippie commune similar to the Spahn Ranch.  Likewise, in retrospect an early scene in The Return of Count Yorga which sees the vampires clawing their way out of their graves might encourage the viewer to draw comparisons with the post-Night of the Living Dead (George A Romero, 1968) zombie picture as much as with the iconography of vampire films. As a matter of fact, in Vampire Cinema David Pirie suggested Night of the Living Dead, which reinvented the zombie as a flesh-eating ghoul, was closer in spirit to the vampire picture owing to its focus on ‘the dead feeding on the living’; Pirie referred to Night of the Living Dead as ‘probably the only modernist reading of the vampire myth’ (Pirie, quoted in Hunt et al, 2014: 5). However, images of zombies clawing their way out of graves in this manner weren’t particularly prevalent during this era. John Gilling’s Plague of the Zombies (1966) features such a sequence, but this specific imagery would become a more familiar part of the iconography of the zombie picture in the late 1970s and 1980s, via the employment of similar sequences in Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (1979) and a number of other Italian zombie pictures (Andrea Bianchi’s Le notti del terrore, 1981, for example), Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead (1985) and, of course, John Landis’ 1983 video for Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’. Released a year after The Return of Count Yorga, Bob Clark’s Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) also featured striking imagery of corpses clawing their way out of their graves, and Clark’s Dead of Night (Deathdream, 1974) incorporated an ironic inversion of this in a sequence in which the zombified protagonist attempts to claw his way back into the earth. Likewise, in retrospect an early scene in The Return of Count Yorga which sees the vampires clawing their way out of their graves might encourage the viewer to draw comparisons with the post-Night of the Living Dead (George A Romero, 1968) zombie picture as much as with the iconography of vampire films. As a matter of fact, in Vampire Cinema David Pirie suggested Night of the Living Dead, which reinvented the zombie as a flesh-eating ghoul, was closer in spirit to the vampire picture owing to its focus on ‘the dead feeding on the living’; Pirie referred to Night of the Living Dead as ‘probably the only modernist reading of the vampire myth’ (Pirie, quoted in Hunt et al, 2014: 5). However, images of zombies clawing their way out of graves in this manner weren’t particularly prevalent during this era. John Gilling’s Plague of the Zombies (1966) features such a sequence, but this specific imagery would become a more familiar part of the iconography of the zombie picture in the late 1970s and 1980s, via the employment of similar sequences in Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (1979) and a number of other Italian zombie pictures (Andrea Bianchi’s Le notti del terrore, 1981, for example), Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead (1985) and, of course, John Landis’ 1983 video for Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’. Released a year after The Return of Count Yorga, Bob Clark’s Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) also featured striking imagery of corpses clawing their way out of their graves, and Clark’s Dead of Night (Deathdream, 1974) incorporated an ironic inversion of this in a sequence in which the zombified protagonist attempts to claw his way back into the earth.

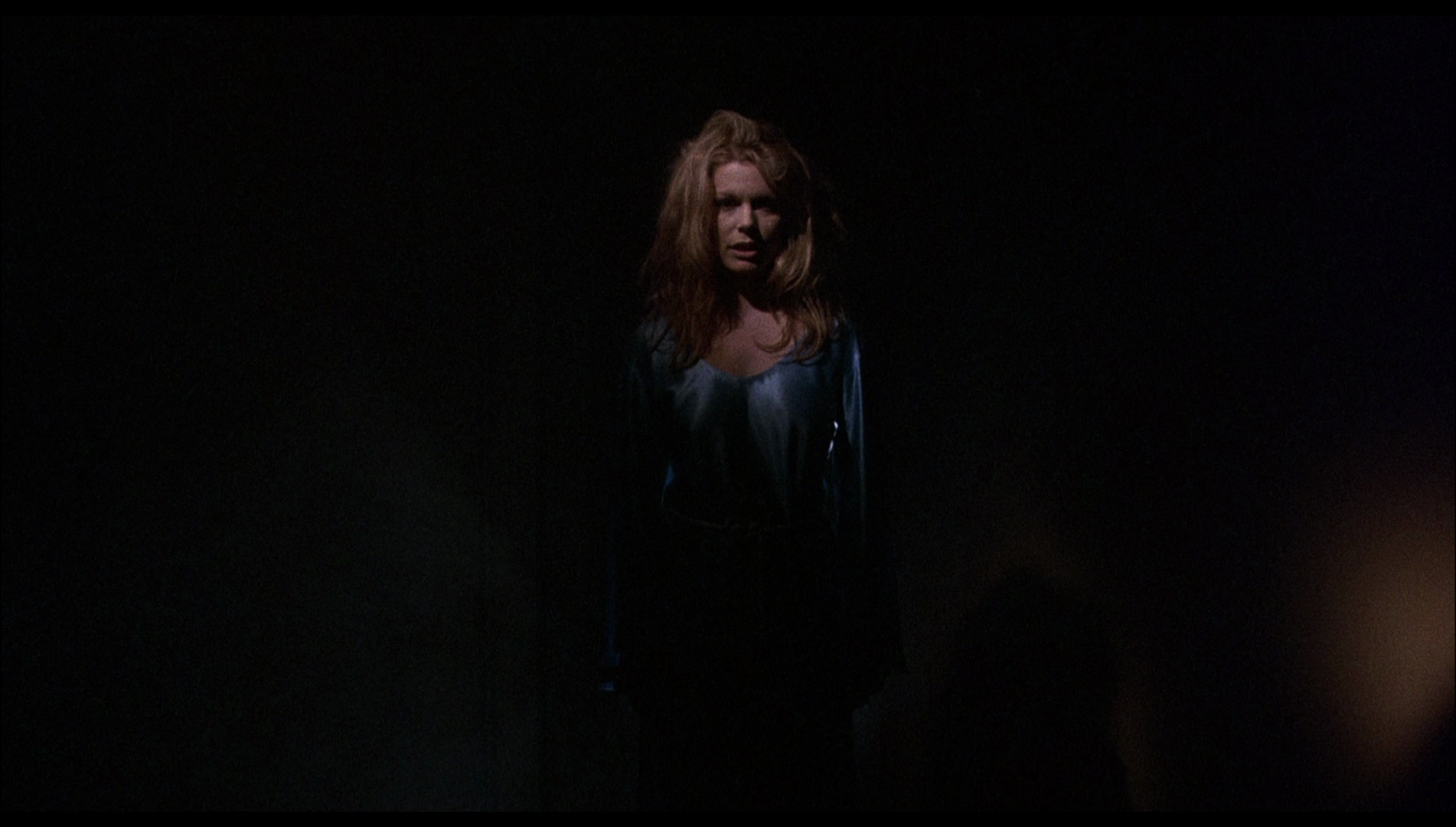

Stacey Abbot has also suggested that both Count Yorga, Vampire and The Return of Count Yorga ‘end on decidedly nihilistic notes that are reminiscent of the hopeless ending of Romero’s film [Night of the Living Dead]’ (Abbott, 2007: 117); Abbott has also noted the use of freeze frames and slow motion during the final sequences of both Count Yorga films, suggesting this establishes another similarity with the ending of Night of the Living Dead (ibid.: 117-8). Filmed en masse and silent, their faces caked in makeup suggesting the decay of the grave and their hands outstretched hungrily, in The Return of Count Yorga the vampires created by Yorga, his ‘brides’, have more in common with the mindless, decaying zombies/ghouls of the post-Night of the Living Dead era, suggesting that when this Bulgarian count invades and infects his prey, turning them to one of his own kind, it results in a kind of degeneracy owing to a lack of cultural ‘purity’. The mindlessness and utter subservience of these women to the will of Yorga also connects them with the newsreel footage of the ‘brainwashed’ women of the Manson cult (for example, the famous footage of them singing on their way to the courtroom). Stacey Abbot has also suggested that both Count Yorga, Vampire and The Return of Count Yorga ‘end on decidedly nihilistic notes that are reminiscent of the hopeless ending of Romero’s film [Night of the Living Dead]’ (Abbott, 2007: 117); Abbott has also noted the use of freeze frames and slow motion during the final sequences of both Count Yorga films, suggesting this establishes another similarity with the ending of Night of the Living Dead (ibid.: 117-8). Filmed en masse and silent, their faces caked in makeup suggesting the decay of the grave and their hands outstretched hungrily, in The Return of Count Yorga the vampires created by Yorga, his ‘brides’, have more in common with the mindless, decaying zombies/ghouls of the post-Night of the Living Dead era, suggesting that when this Bulgarian count invades and infects his prey, turning them to one of his own kind, it results in a kind of degeneracy owing to a lack of cultural ‘purity’. The mindlessness and utter subservience of these women to the will of Yorga also connects them with the newsreel footage of the ‘brainwashed’ women of the Manson cult (for example, the famous footage of them singing on their way to the courtroom).

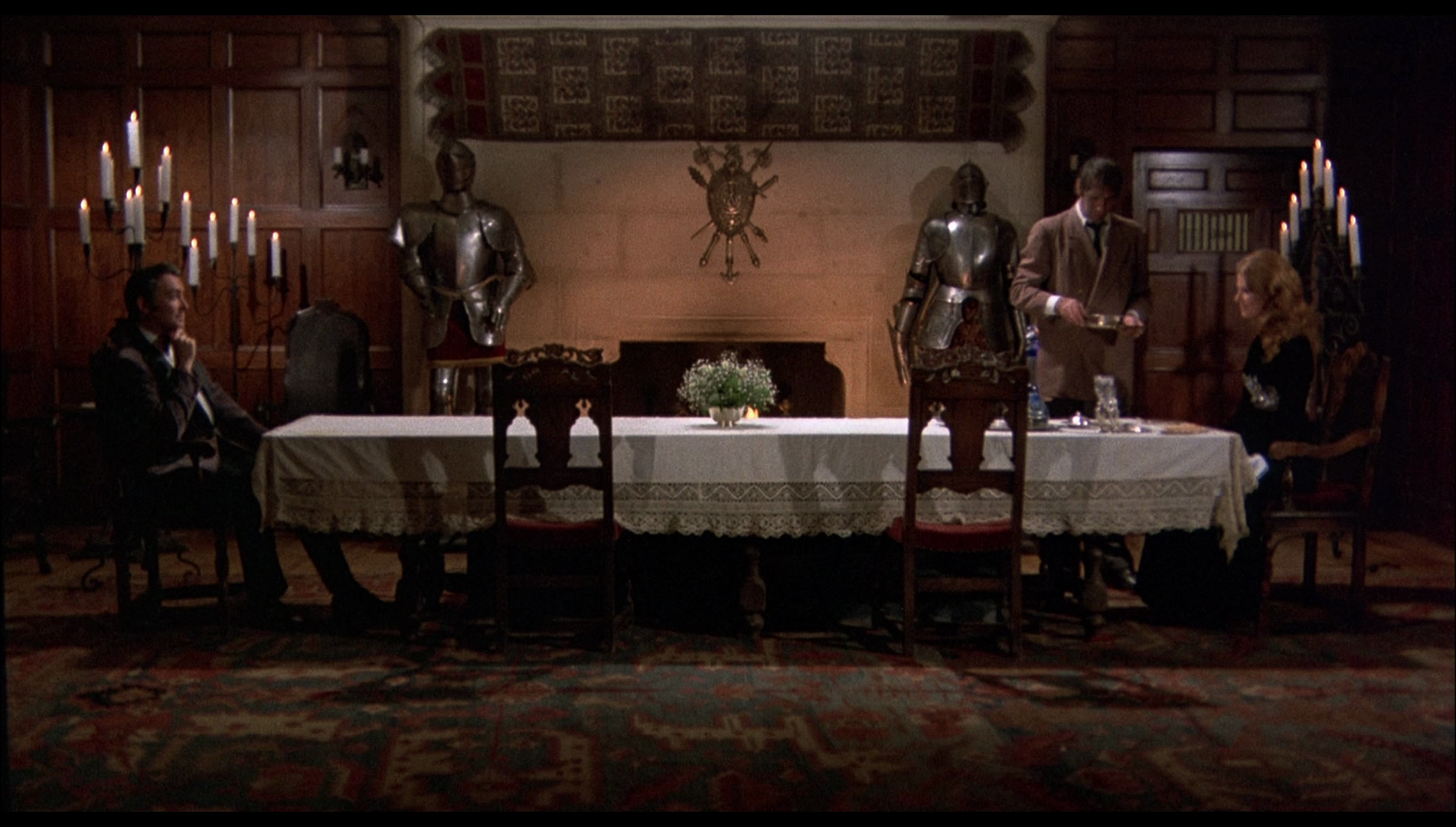

Gregory Waller has argued that in taking the classic screen image of the vampire and transplanting him to a modern day setting, the Count Yorga pictures offer a ‘transition between stories like I, Desire and [Stephen] King’s ’Salem’s Lot, in which a town in modern America is invaded by a European vampire who turns the local citizens into his undead slaves’ (Waller, 2010: 236). Moving the setting of the traditional vampire picture into present day Los Angeles enriches the film’s focus on folklore. The first film makes much of Yorga’s association with the occult, introducing him via a séance he is conducting in an attempt to communicate with Donna’s deceased mother, and showing him using hypnotism to calm Donna. (He also communicates with her telepathically, shown via the use of tight close-ups of Quarry’s face and his disembodied voice on the audio track: ‘You will do everything I say’, he tells her wordlessly, ‘Whenever and wherever I say it’.) Later in the film, Dr Hayes questions Yorga about his belief in the occult; a similar sequence takes place in The Return of Count Yorga. Kim Newman has argued that ‘[t]his Count [Yorga] may look like an old-world monster, but he is hip to the California of gurus and self-realisation therapies’ (Newman, 2011: 43). In a sequence in Count Yorga, Vampire, Hayes and Yorga discuss their respective interests, Hayes telling the vampire that he is ‘in research. I’m a blood specialist’. ‘That must be fascinating work’, Yorga asserts dryly, before telling Hayes that he is involved in the ‘mystic arts’. ‘Have your studies been intensive or is it just a hobby’, Hayes asks. ‘A true hobby, Dr Hayes, is probably the most intense study of all’, Yorga reminds Hayes.  The Return of Count Yorga is inarguably a more intense and nightmarish film than its predecessor, featuring a number of fascinating sequences: the murder of the Nelsons, with its echoes of the Tate-La Bianca killings; the flashbacks that Cynthia experiences towards these murders, bathed in red light and shot via canted angles to emphasise their nightmarish qualities; the sequence in which Cynthia is pursued by Yorga’s brides through the Count’s house, passing through rooms of mannequins and suits of armour, her passage through the house haunted by the disembodied laughter of her pursuers. The photography, by Bill Butler, is head and shoulders above the photography in the first picture, contributing to its sense of atmosphere. Both films build toward bleak, nihilistic conclusions, suggesting the ineffectuality of the vampire hunters in these films: there is no Van Helsing to guide the actions of these modern day vampire hunters, and the rationality of the modern world works against the success of their attempts to rid the world of vampires. The Return of Count Yorga is inarguably a more intense and nightmarish film than its predecessor, featuring a number of fascinating sequences: the murder of the Nelsons, with its echoes of the Tate-La Bianca killings; the flashbacks that Cynthia experiences towards these murders, bathed in red light and shot via canted angles to emphasise their nightmarish qualities; the sequence in which Cynthia is pursued by Yorga’s brides through the Count’s house, passing through rooms of mannequins and suits of armour, her passage through the house haunted by the disembodied laughter of her pursuers. The photography, by Bill Butler, is head and shoulders above the photography in the first picture, contributing to its sense of atmosphere. Both films build toward bleak, nihilistic conclusions, suggesting the ineffectuality of the vampire hunters in these films: there is no Van Helsing to guide the actions of these modern day vampire hunters, and the rationality of the modern world works against the success of their attempts to rid the world of vampires.

Video

Both films are uncut and included on a single double-layered Blu-ray disc. Count Yorga, Vampire runs for 92:47 mins; The Return of Count Yorga runs for 97:05 mins. Both films are presented in their original screen ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec and each take up approximately 21Gb of space. In the case of both films, Arrow worked with transfers from the original film materials provided for them by MGM. These are doubtless the same materials used for the US DVD release of both pictures from MGM (under the ‘Midnight Movies’ banner) and the more recent US Blu-ray releases of the first film, from Twilight Time, and the second picture, from Shout! Factory. Both films are uncut and included on a single double-layered Blu-ray disc. Count Yorga, Vampire runs for 92:47 mins; The Return of Count Yorga runs for 97:05 mins. Both films are presented in their original screen ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec and each take up approximately 21Gb of space. In the case of both films, Arrow worked with transfers from the original film materials provided for them by MGM. These are doubtless the same materials used for the US DVD release of both pictures from MGM (under the ‘Midnight Movies’ banner) and the more recent US Blu-ray releases of the first film, from Twilight Time, and the second picture, from Shout! Factory.

As noted above, The Return of Count Yorga is much more impressively photographed than the first film in the pairing. Count Yorga, Vampire features some strange compositions, with heads disappearing off the top of the screen at times, even during dialogue scenes; this seems to be simply down to carelessness in the original photography rather than suggesting that this presentation is framed too tightly. (A quick check of MGM’s R1 DVD reveals the compositions are the same on that presentation too.) There are also some shots in Count Yorga, Vampire, shot in low light on what seem to be short telephoto lenses with wide open apertures (and shallow depth of field), that drift in and out of focus as the actors move about the sets, as if the focus puller was a little slow off the mark; again, this is a feature of the original photography, a quality that defines the nature of this film, shot quickly and cheaply.  Both presentations share the same qualities. From the opening moments of Count Yorga, Vampire, the extremely rich colour consistency of the HD presentation is noticeable, in comparison with the older DVD releases of the films, from the opening titles which feature bright red text. This is also impressive during the flashbacks Cynthia experiences in The Return of Count Yorga to the massacre of her family, bathed in red light. There’s an impressive level of detail on display throughout both films. Good contrast levels are present, with defined midtones and deep, rich shadows (though in some of the darker scenes the shadows seem noticeably ‘crushed’). There’s quite a bit of day for night footage present in both pictures, however, which mitigates this and the night scenes aren’t wholly convincing at times owing to the original photography; nevertheless, the material is handled very well within these HD presentations. There’s very little damage present in either transfer, though in Count Yorga, Vampire, there’s a little instability within the image, which looks like gate weave, during the opening séance. It’s barely noticeable, but present nonetheless. Both presentations are supported with solid encodes which ensure that the films retain the organic structure of 35mm film; this results in a pleasingly film-like viewing experience. Both presentations share the same qualities. From the opening moments of Count Yorga, Vampire, the extremely rich colour consistency of the HD presentation is noticeable, in comparison with the older DVD releases of the films, from the opening titles which feature bright red text. This is also impressive during the flashbacks Cynthia experiences in The Return of Count Yorga to the massacre of her family, bathed in red light. There’s an impressive level of detail on display throughout both films. Good contrast levels are present, with defined midtones and deep, rich shadows (though in some of the darker scenes the shadows seem noticeably ‘crushed’). There’s quite a bit of day for night footage present in both pictures, however, which mitigates this and the night scenes aren’t wholly convincing at times owing to the original photography; nevertheless, the material is handled very well within these HD presentations. There’s very little damage present in either transfer, though in Count Yorga, Vampire, there’s a little instability within the image, which looks like gate weave, during the opening séance. It’s barely noticeable, but present nonetheless. Both presentations are supported with solid encodes which ensure that the films retain the organic structure of 35mm film; this results in a pleasingly film-like viewing experience.

Some screen grabs comparing this new Blu-ray presentation of the first film with the DVD release from MGM are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented, for both films, via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is rich and deep, evident from the rumbling main titles theme of the first film which is offset by shrill violins. Audio quality is consistent throughout both presentations. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are also provided. These are clean, easy to read, true to the dialogue and free of errors.

Extras

The disc includes, as contextual material, the following:  - Audio commentaries for both films by critics/film historians David Del Valle and C Courtney Joyner. These informative commentary tracks are packed within information and opinion about the films. The two commentators are warm and enthusiastic. They discuss the differences between the Yorga pictures and the other vampire films of the era, and praise Quarry’s performance as the titular count – and his willingness to engage with the films’ fans in the latter years of his life. They reflect on the careers of some of the cast and crew involved in the making of these films. They talk about some of the first film’s specific references to Stoker’s Dracula. - Audio commentaries for both films by critics/film historians David Del Valle and C Courtney Joyner. These informative commentary tracks are packed within information and opinion about the films. The two commentators are warm and enthusiastic. They discuss the differences between the Yorga pictures and the other vampire films of the era, and praise Quarry’s performance as the titular count – and his willingness to engage with the films’ fans in the latter years of his life. They reflect on the careers of some of the cast and crew involved in the making of these films. They talk about some of the first film’s specific references to Stoker’s Dracula.

- A new video appreciation by Kim Newman (33:02). Here, in a newly filmed interview, Newman discusses the history of the Yorga films and the first picture’s origins as a planned softcore sex film, before it evolved into a more conventional horror film. He reflects on Quarry’s career as an actor. Newman discusses the relationship between the first film and its sequel. He talks about the success of the film, suggesting that the popularity of Dark Shadows may have both influenced the Count Yorga pictures and explained the film’s reception. - Trailers: Count Yorga, Vampire (2:25) and The Return of Count Yorga (1:39). - A stills gallery (1:25)

Overall

The Count Yorga pictures were a significant step away from the paradigms of the Hammer Gothics. Both films are entertaining enough, though The Return of Count Yorga is a little more ‘arty’ and confident, straying away from the narrative of Stoker’s Dracula (which Count Yorga, Vampire follows quite closely) and forging its own ground. The vampires are more interesting in the second picture, seeming more like the revenants of European folklore than anything else, and the film has some strong visual and thematic connections with the post-Romero zombie picture. The films are culturally important for spearheading the tendency to bring the Gothic vampire into the present day that would characterise the likes of John Llewellyn Moxey’s The Night Stalker (1972) and the memorable 1976 episode of Starsky & Hutch, ‘The Vampire’, in which the titular detectives stalk a vampire (John Saxon) through the city. In their use of the traditional iconography of the vampire, established in Tod Browning’s Dracula, and their juxtaposition of this with their present-day setting, the Count Yorga pictures represent a significant stage in the evolution of the vampire film. The Blacula pictures, riding on the coat- (or cape-) tails of the Yorga films, advance the project begun in these pictures. Arguably, the most significant turning point for the American vampire film took place a few years later, with George A Romero’s Martin (1977); in that film, aside from depicting vampirism ambiguously (suggesting that it was as much pathological as supernatural, something hinted at in the dialogue in the Yorga films), Romero made his vampire (John Amplas) an American teenager – discarding the idea that the vampire must be a ‘foreign’ invader. The Count Yorga pictures were a significant step away from the paradigms of the Hammer Gothics. Both films are entertaining enough, though The Return of Count Yorga is a little more ‘arty’ and confident, straying away from the narrative of Stoker’s Dracula (which Count Yorga, Vampire follows quite closely) and forging its own ground. The vampires are more interesting in the second picture, seeming more like the revenants of European folklore than anything else, and the film has some strong visual and thematic connections with the post-Romero zombie picture. The films are culturally important for spearheading the tendency to bring the Gothic vampire into the present day that would characterise the likes of John Llewellyn Moxey’s The Night Stalker (1972) and the memorable 1976 episode of Starsky & Hutch, ‘The Vampire’, in which the titular detectives stalk a vampire (John Saxon) through the city. In their use of the traditional iconography of the vampire, established in Tod Browning’s Dracula, and their juxtaposition of this with their present-day setting, the Count Yorga pictures represent a significant stage in the evolution of the vampire film. The Blacula pictures, riding on the coat- (or cape-) tails of the Yorga films, advance the project begun in these pictures. Arguably, the most significant turning point for the American vampire film took place a few years later, with George A Romero’s Martin (1977); in that film, aside from depicting vampirism ambiguously (suggesting that it was as much pathological as supernatural, something hinted at in the dialogue in the Yorga films), Romero made his vampire (John Amplas) an American teenager – discarding the idea that the vampire must be a ‘foreign’ invader.

Count Yorga, Vampire is rather roughly put together, with some careless photography evident throughout (though the sets and actors are lit beautifully, it has to be said). Photographed by the great Bill Butler, The Return of Count Yorga is a much more polished affair. Arrow’s Blu-ray release is heaven sent, in the sense that it collects both pictures, and the presentations of both films on this disc is very good (albeit, other than featuring a stronger encode, nearly identical to the presentations of both films on the Blu-ray releases from Shout! and Twilight Time in the US). This, combined with the exclusive extras on this disc, should ensure this release is a must-buy for fans of the films, and represents a significant upgrade from the films’ DVD-era releases. References: Abbott, Stacey, 2007: Celluloid Vampires: Life After Death in the Modern World. The University of Texas Press Hunt, Leon et al, 2014: ‘Introduction: Sometimes They Come Back – The Vampire and Zombie On Screen’. In: Hunt, Leon et al (eds), 2014: Screening the Undead: Vampire and Zombies in Film and Television. London: I B Tauris: 1-18 Newman, Kim, 2011: Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s. London: Bloomsbury (Revised Edition) Sullivan, Tim, 2004: ‘My Dinner with Yorga’. [Online.] http://www.iconsoffright.com/SHOCK_09.htm Waller, Gregory, 2010: The Living and the Undead: Slaying Vampires, Exterminating Zombies. University of Illinois Press Visual comparison of Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Count Yorga, Vampire with the film’s precious R1 DVD release from MGM. Arrow’s Blu-ray:

MGM’s older DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

MGM’s older DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

MGM’s older DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

MGM’s older DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

MGM’s older DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

MGM’s older DVD:

Count Yorga, Vampire

The Return of Count Yorga

|

|||||

|