|

The Film

Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate AKA The Bloodstained Butterfly (Duccio Tessari, 1971) Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate AKA The Bloodstained Butterfly (Duccio Tessari, 1971)

NB. For this review, we were presented with a check disc of the DVD included in the package only – and not the Blu-ray disc.

Coming during a period of increased productivity within (and popularity of) the thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller; or giallo all’italiana ), following a decline in production of the westerns all’italiana (Italian-style Westerns/Spaghetti Westerns) whose popularity had buoyed Italian filmmaking during the mid- to late-1960s, Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate (The Bloodstained Butterfly , 1971) was made by a director, Duccio Tessari, who had during the 1960s been one of the key figures within the western all’italiana . As a director of Westerns, Tessari had made the two much-imitated ‘Ringo’ pictures starring Giuliano Gemma, Una pistola per Ringo (A Gun for Ringo , 1965) and Il ritorno di Ringo (The Return of Ringo , 1966). In fact, Tessari’s decision in the early 1970s to turn his attention away from the western all’italiana towards the thrilling all’italiana could be said to be metonymic of the Italian film industry in general.

In the year prior to the production of The Bloodstained Butterfly , Tessari had already directed another example of the thrilling , La morte risale a ieri sera (Death Occurred Last Night , 1970). That film, a gritty examination of the hunt by a policeman and a father for a missing young woman, deviated from the tropes of the more high profile examples of the thrilling all’italiana that, during the 1970s and beyond, would come to define this style of filmmaking for predominantly non-Italian audiences (and would be symbolised through the baroque thrillers directed by the likes of Dario Argento). Despite what fan discourse might suggest, the specific paradigms of the thrilling all’italiana are remarkably diverse and extraordinarily difficult to pin down with any certainty – which means that debates about the Italian-style thriller and what is or isn’t a part of it often echo discussions of the parameters of film noir – suggesting that, like film noir , the thrilling all’italiana is perhaps best considered as a ‘style’ rather than a ‘genre’ (the Italian-style of the denominator). However, particularly for English-speaking audiences the thrilling all’italiana has come to be associated with a specific subset of the Italian-style thriller: the Agatha Christie-like whodunits which feature horror elements (which are sometimes supernatural in nature), an amateur sleuth and baroque setpieces. In its emphasis on almost semidocumentary realism and its focus on a police investigation, Death Occurred Last Night bucked this trend, highlighting the similarities between many examples of the thrilling all’italiana and those American films noir of the 1950s that focused on psychosexual terror (such as Joseph Losey’s The Prowler , 1951).

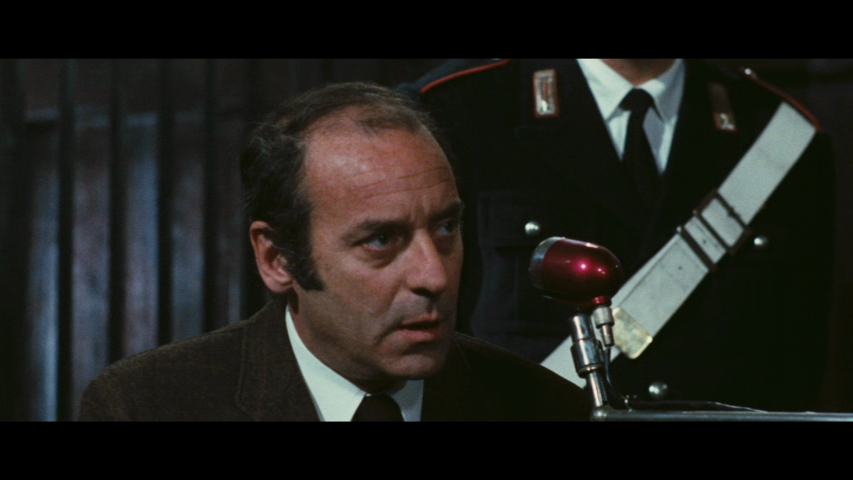

The Bloodstained Butterfly begins with the murder of pretty French student Françoise Pigaut (Carole André) in a park. The only witnesses seem to be two young children. The police, led by Inspector Berardi (Silvano Tranquilli), arrive on the scene and conclude that Françoise was killed with a knife. The only other clue seems to be the fact that at the time of the attack which killed her, Françoise was carrying a record: Tchaikovsky’s ‘Piano Concerto No 1’. The Bloodstained Butterfly begins with the murder of pretty French student Françoise Pigaut (Carole André) in a park. The only witnesses seem to be two young children. The police, led by Inspector Berardi (Silvano Tranquilli), arrive on the scene and conclude that Françoise was killed with a knife. The only other clue seems to be the fact that at the time of the attack which killed her, Françoise was carrying a record: Tchaikovsky’s ‘Piano Concerto No 1’.

The police conduct a thorough scientific investigation, concluding from epithelials found at the crime scene that the attacker was a Caucasian male. Berardi suggests that Françoise must also have known her killer: ‘A girl like that doesn’t go on a date with a stranger at six pm’, he asserts. Berardi believes that Françoise’s killer was rejected by her, and this was the reason for her murder.

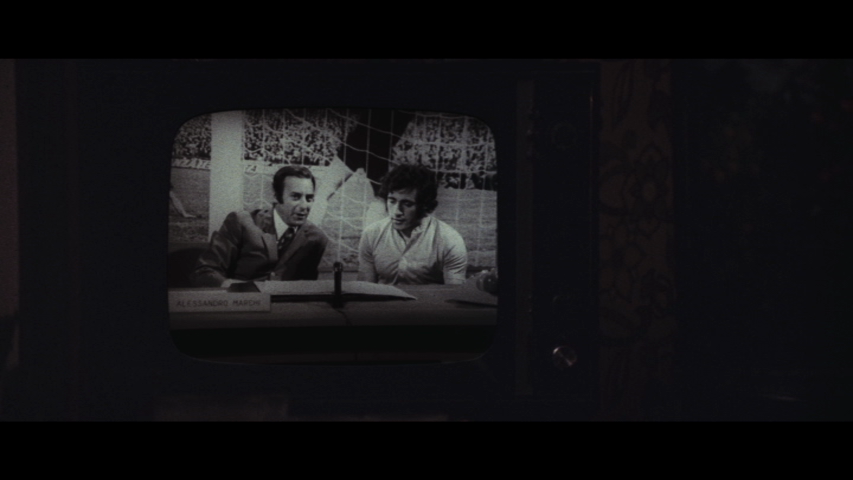

Meanwhile, Françoise’s friend Sarah (Wendy D’Olive) begins a tentative relationship with morose music student Giorgio (Helmut Berger). A witness who claims to have seen Françoise’s killer fleeing the park points her finger at Alessandro (Giancarlo Sbragia), Sarah’s father and a sports pundit on the television. Alessandro is soon placed on trial for the murder of Françoise. It seems that Alessandro will most certainly be found guilty of Françoise’s murder, despite the defence’s attempts to cast doubts upon the veracity of the claims made by the woman who suggested she saw Alessandro fleeing the scene of Françoise’s murder.

However, after Alessandro has been convicted of the murder, it seems that Alessandro’s wife Maria (Ida Galli) has been conspiring with Alessandro’s defence counsel, Giulio Cordaro (Gunther Stoll), to ensure her husband is sent to prison: Maria and Giulio have been conducting a passionate affair. When a prostitute is found murdered in near-identical circumstances to Françoise, doubt is cast upon the conviction of Alessandro for Françoise’s murder. Meanwhile, Maria’s relationship with Giulio becomes more fractious when she interrupts him in the act of attempting to force himself sexually upon Sarah. However, after Alessandro has been convicted of the murder, it seems that Alessandro’s wife Maria (Ida Galli) has been conspiring with Alessandro’s defence counsel, Giulio Cordaro (Gunther Stoll), to ensure her husband is sent to prison: Maria and Giulio have been conducting a passionate affair. When a prostitute is found murdered in near-identical circumstances to Françoise, doubt is cast upon the conviction of Alessandro for Françoise’s murder. Meanwhile, Maria’s relationship with Giulio becomes more fractious when she interrupts him in the act of attempting to force himself sexually upon Sarah.

Alessandro seems to be vindicated when his mistress comes forwards and provides him with an alibi for the evening when Françoise was murdered. As Alessandro is freed form prison and reunited with his family, Berardi turns his attention towards Giorgio, who, Berardi discovers, bought two distinctive flickknives identical to the ones used in the murders of Françoise and the prostitute.

Like many examples of the thrilling all’italiana , The Bloodstained Butterfly returns time and time again to the moment of trauma, the killing of Françoise , via the use of analepses. These analepses, like the infamous ‘lying flashback’ in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950), aren’t to be taken as objective representations of the events depicted within them, however: like the various perspectives of the pivotal murder narrated in Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s modernist short story ‘In a Grove’ (1922) or Kurosawa Akira’s 1950 film adaptation of that novel as Rashomon (and, to give a more contemporaneous example, Mario Bava’s Rashomon -influenced sex comedy Quattro volte… quella notte /Four Times That Night , 1971), each flashback presented in The Bloodstained Butterfly seems to complicate rather than explain the context in which Françoise ’ murder took place and the reasons why it happened. The film’s non-linear approach is foreshadowed in the use of an aphorism, presented via onscreen text, in the opening moments of the picture, which states that neither the past nor the future exist, ‘Therefore, only the present exist, but it can be made up of both the past and the future, because it is the point at which they meet’.

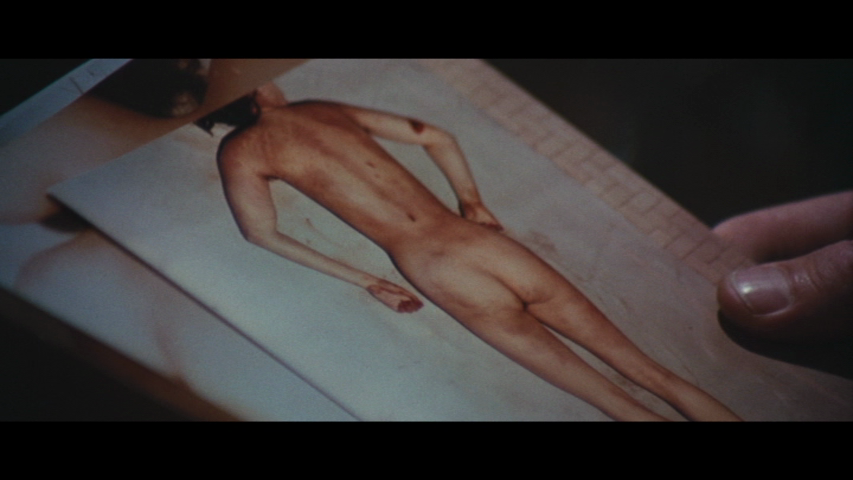

Devoting equal time to the crimes, their victims and perpetrators, as to the police investigation into them (including some detailed focus on the labwork involved in the investigation into Françoise ’s murder), the picture is equal parts thrilling all’italiana and police procedural-style poliziesco all’italiana . In this sense, The Bloodstained Butterfly allies itself with other examples of the 1970s thrilling all’italiana that intersect with the poliziesco pictures of the same era, including Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters? /The Co-Ed Murders , 1974) and Mario Caiano’s …A tutte le auto della polizia… (Calling All Police Cars /The Maniac Responsible , 1975). Much of The Bloodstained Butterfly , especially those sequences focusing on the police investigation, have a semidocumentary approach (in the manner established in American films noir by post-war semidocumentary pictures such as Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street , 1945, and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City , 1948): these sequences feature much seemingly ‘spontaneous’, documentary-like camerawork, alongside – as mentioned above – a focus on the laboratory investigation into the crime and the dogwork of police investigation (interviewing suspects, putting forward hypotheses, reconstructing the crime through oratory), both of which are hallmarks of the semidocumentary form. (The sense of authenticity within the lab scenes is carried over into the striking use of what appear to be three genuine photographs of the corpse of a murder victim, meant to act as a visual representation of the wounds inflicted upon Françoise , that are passed amongst the technicians and investigators.) Midway through its narrative, The Bloodstained Butterfly moves out of the labs and city streets and into the courtroom, offering a legal drama in the manner of Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion (1959) and a space in which both the prosecution and defence may offer differing accounts of the murder of Françoise. Devoting equal time to the crimes, their victims and perpetrators, as to the police investigation into them (including some detailed focus on the labwork involved in the investigation into Françoise ’s murder), the picture is equal parts thrilling all’italiana and police procedural-style poliziesco all’italiana . In this sense, The Bloodstained Butterfly allies itself with other examples of the 1970s thrilling all’italiana that intersect with the poliziesco pictures of the same era, including Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters? /The Co-Ed Murders , 1974) and Mario Caiano’s …A tutte le auto della polizia… (Calling All Police Cars /The Maniac Responsible , 1975). Much of The Bloodstained Butterfly , especially those sequences focusing on the police investigation, have a semidocumentary approach (in the manner established in American films noir by post-war semidocumentary pictures such as Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street , 1945, and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City , 1948): these sequences feature much seemingly ‘spontaneous’, documentary-like camerawork, alongside – as mentioned above – a focus on the laboratory investigation into the crime and the dogwork of police investigation (interviewing suspects, putting forward hypotheses, reconstructing the crime through oratory), both of which are hallmarks of the semidocumentary form. (The sense of authenticity within the lab scenes is carried over into the striking use of what appear to be three genuine photographs of the corpse of a murder victim, meant to act as a visual representation of the wounds inflicted upon Françoise , that are passed amongst the technicians and investigators.) Midway through its narrative, The Bloodstained Butterfly moves out of the labs and city streets and into the courtroom, offering a legal drama in the manner of Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion (1959) and a space in which both the prosecution and defence may offer differing accounts of the murder of Françoise.

The Bloodstained Butterfly complicates its narrative by having a second murder, that of the prostitute, committed part-way through the film, using the same weapon and in a nearby location to the murder of Françoise . This seems to vindicate Alessandro, and the fact of this second murder leads to Alessandro’s release from prison and reunification with his family. However, the viewer may be left questioning whether or not this second murder has been committed by the same person who killed Françoise: as Berardi notes, the circumstances of the crime are similar but the motivations appear to be different. That said, there are some profound holes in his logic – as if the very fact that the victim was a prostitute and therefore, in the detective’s argument, available to any punter for money, rules out the suggestion that the murder was a sex crime: ‘The first victim was a decent girl’, Berardi asserts, ‘The second is a prostitute. In the first case, the motive was clearly sexual. But this reason does not apply with the second crime. A little money would have left him satisfied with a girl like that’. The suggestion that one of the two murders may or may not have been committed by the same killer links The Bloodstained Butterfly to Dario Argento’s Tenebre (1982). (Berardi even receives an Argento-esque telephone call, in which the killer whispers to him, after the murder of the prostitute, ‘I’ve already killed twice and got away with it. I won’t stop. I’ll kill again’.)

In some ways, Tessari’s film might be compared with what is perhaps the most recognisable (at least, to non-Italian audiences) filone /subtype within examples of the thrilling all’italiana : narratives that feature an amateur sleuth investigating a crime or series of crimes and whose investigations run parallel with, and often intersect catastrophically, with the official police investigation. However, interestingly in this film the amateur sleuth isn’t really revealed to be such until the climax of the narrative. Nevertheless, unlike many examples of the thrilling all’italiana , The Bloodstained Butterfly doesn’t have a single protagonist and focuses instead on an ensemble: this is emphasised in the film’s opening moments, in which the key players within the drama (Françoise, Sarah, Alessandro, and so on) are introduced via shots of them that are accompanied with onscreen text identifying them and their relationships with one another. (An inattentive viewer might even mistake this for a cast list, owing to the manner in which it is presented.) Although, given the ensemble cast, his status as the protagonist is questionable at best, Giorgio’s interest in music links the film with the examples of the thrilling all’italiana that are sulla stesso filone Argento (in the style of Dario Argento’s films), following the trend established by Argento in his directorial debut L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage , 1969) of having characters with ‘artistic’ careers (writers, musicians, dancers, singers, photographers) as his films’ main protagonists, and having these characters usually fill the role of the amateur sleuth within his pictures. In some ways, Tessari’s film might be compared with what is perhaps the most recognisable (at least, to non-Italian audiences) filone /subtype within examples of the thrilling all’italiana : narratives that feature an amateur sleuth investigating a crime or series of crimes and whose investigations run parallel with, and often intersect catastrophically, with the official police investigation. However, interestingly in this film the amateur sleuth isn’t really revealed to be such until the climax of the narrative. Nevertheless, unlike many examples of the thrilling all’italiana , The Bloodstained Butterfly doesn’t have a single protagonist and focuses instead on an ensemble: this is emphasised in the film’s opening moments, in which the key players within the drama (Françoise, Sarah, Alessandro, and so on) are introduced via shots of them that are accompanied with onscreen text identifying them and their relationships with one another. (An inattentive viewer might even mistake this for a cast list, owing to the manner in which it is presented.) Although, given the ensemble cast, his status as the protagonist is questionable at best, Giorgio’s interest in music links the film with the examples of the thrilling all’italiana that are sulla stesso filone Argento (in the style of Dario Argento’s films), following the trend established by Argento in his directorial debut L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage , 1969) of having characters with ‘artistic’ careers (writers, musicians, dancers, singers, photographers) as his films’ main protagonists, and having these characters usually fill the role of the amateur sleuth within his pictures.

The film paints a portrait of masculinity which is dysfunctional: Alessandro is a philanderer, and possibly a murderer; the lawyer Giulio is quick to jump into bed with Alessandro’s wife and, given his sexual assault upon Sarah for which he is unrepentant when challenged by Maria, both has an unhealthy sexual interest in young women and is willing to force himself upon a woman to satisfy his own needs. His assault upon Sarah, interrupted by Maria, sticks a pin into Italian machismo. ‘I was helping Sarah with her homework’, he protests unconvincingly before conceding that he was indeed assaulting Sarah: ‘All men like young girls’, he declares lasciviously, ‘They’re so adorable. For us, they’re like a shot at happiness’. Finally, in the midst of this dysfunctional masculinity, Giorgio is neurotic and alienated, apparently suffering from a profound sense of ennui which sees him disconnected from the world him and unable to form warm or close relationships with others. This manifests itself in a spiteful manner and a reliance on alcohol: early in the film, Giorgio is shown staggering along a narrow street whilst a middle-aged couple reflect negatively on his drunken state. When visiting his family in their large home and eating with his parents, Giorgio’s disengagement from them is emphasised through the use of a wide-angle lens which separate the characters from one another within the space of the dining room whilst also offering a strong sense of visual disturbance through the pronounced barrel distortion of the lens. Speaking with his father, Giorgio asserts that ‘Our family motto reads: “Born a bastard to become a king”. I didn’t have the fortune to be a king, but I wasn’t lucky enough to be a bastard either’. Giorgio’s father reflects on the ways in which society has changed, commenting on how attitudes towards traditional patriarchal privilege have been challenged: ‘The world is changing’, he says, ‘When I was your age, dwellings such as this [Giorgio’s apartment] would have been the servant’s quarters. Today, they house young protestors with big bang accounts’. In response to this, Giorgio tells his father, ‘Everything that surrounds me and everything that you and people like you have taught me makes me sick’. In exploring this issue, and the relationships between the Giorgios, Françoises and Sarahs of the world with their parent generation (represented through Giorgio’s father, Maria, Alessandro and Giulio), The Bloodstained Butterfly places inter-generational conflict and changing attitudes towards gender and privilege under its lens. However, as Giorgio’s father notes with reference to Giorgio’s attitude, ‘You’re one of the lucky ones, and yet you can’t even life a finger to raise your despair’. The film paints a portrait of masculinity which is dysfunctional: Alessandro is a philanderer, and possibly a murderer; the lawyer Giulio is quick to jump into bed with Alessandro’s wife and, given his sexual assault upon Sarah for which he is unrepentant when challenged by Maria, both has an unhealthy sexual interest in young women and is willing to force himself upon a woman to satisfy his own needs. His assault upon Sarah, interrupted by Maria, sticks a pin into Italian machismo. ‘I was helping Sarah with her homework’, he protests unconvincingly before conceding that he was indeed assaulting Sarah: ‘All men like young girls’, he declares lasciviously, ‘They’re so adorable. For us, they’re like a shot at happiness’. Finally, in the midst of this dysfunctional masculinity, Giorgio is neurotic and alienated, apparently suffering from a profound sense of ennui which sees him disconnected from the world him and unable to form warm or close relationships with others. This manifests itself in a spiteful manner and a reliance on alcohol: early in the film, Giorgio is shown staggering along a narrow street whilst a middle-aged couple reflect negatively on his drunken state. When visiting his family in their large home and eating with his parents, Giorgio’s disengagement from them is emphasised through the use of a wide-angle lens which separate the characters from one another within the space of the dining room whilst also offering a strong sense of visual disturbance through the pronounced barrel distortion of the lens. Speaking with his father, Giorgio asserts that ‘Our family motto reads: “Born a bastard to become a king”. I didn’t have the fortune to be a king, but I wasn’t lucky enough to be a bastard either’. Giorgio’s father reflects on the ways in which society has changed, commenting on how attitudes towards traditional patriarchal privilege have been challenged: ‘The world is changing’, he says, ‘When I was your age, dwellings such as this [Giorgio’s apartment] would have been the servant’s quarters. Today, they house young protestors with big bang accounts’. In response to this, Giorgio tells his father, ‘Everything that surrounds me and everything that you and people like you have taught me makes me sick’. In exploring this issue, and the relationships between the Giorgios, Françoises and Sarahs of the world with their parent generation (represented through Giorgio’s father, Maria, Alessandro and Giulio), The Bloodstained Butterfly places inter-generational conflict and changing attitudes towards gender and privilege under its lens. However, as Giorgio’s father notes with reference to Giorgio’s attitude, ‘You’re one of the lucky ones, and yet you can’t even life a finger to raise your despair’.

Video

Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were provided with the a check disc of the DVD copy only, and not the Blu-ray disc. Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were provided with the a check disc of the DVD copy only, and not the Blu-ray disc.

Shot in Techniscope, The Bloodstained Butterfly benefits from a pleasing presentation on this DVD. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement. Upon disc startup, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the ‘Italian version’ or the ‘English version’ – selecting one or the other will not only ensure that the film defaults to the Italian or English language audio tracks, but also determines whether the viewer is presented with onscreen text (within the film) in Italian or English.

The opening titles sequence, presumably printed optically, is a little murky and indistinct, but once this ends and the film ‘proper’ begins, we are presented with a nicely balanced image with a good level of detail present throughout. The production seems to have made much use of then-modern zoom lenses (often to suggest a sort of ‘snatched’ documentary-style realism, as if the camera is ‘listening in’ on the characters), and zoom lenses of this vintage tended to have a softness to their rendering compared with prime/fixed focal length lenses. This is reflected in the film’s aesthetic. Nevertheless, within this presentation there’s a pleasing sense of depth to the photography, where needed. The contrast levels on display here offer perhaps the biggest improvement over previous home video presentations, ensuring that the film’s many low light sequences now have a greater sense of clarity to them.

The film is uncut and, on the DVD, runs for 99:07 mins (PAL). This version of the film features some additional material at the front-end of the narrative, in comparison with some of the film’s previous home video releases.

Audio

The viewer is presented with the option of watching the film in Italian, with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue, or English, with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. (Both tracks are in Dolby Digital 1.0 mono.) As, like many Italian pictures of this period, the film was an international co-production shot with the intention of local dubs being produced for different markets, both tracks are of course as legitimate as one another, though given the fact that the director was Italian, some viewers may prefer to choose the Italian language audio track. Certainly, in terms of the content of the dialogue, there’s little difference between the Italian and English dubs. Both audio tracks are clear and audible throughout, although the English language track seems to have a little more range.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Kim Newman and Alan Jones . Newman and Jones provide a characteristically enthusiastic commentary track. Their comments are lively and entertaining, filled with anecdotes about the picture and offering a strong attempt to contextualise the film.

- Optional introduction by Helmut Berger (1:20) . Berger offers a brief introduction to the main feature (in English).

- ‘Murder in B Flat Minor’ (26:55) . Here, in a new video essay, Troy Howarth examines The Bloodstained Butterfly . Howarth situates the film within the context of the other examples of the thrilling all’italiana made during the early 1970s. Reflecting on Tessari’s career, Howarth discusses the director’s association with the western all’italiana and various pepla of the early 1960s. He talks about The Bloodstained Butterfly ’s relationship with the thrilling and the poliziesco all’italiana .

- ‘A Butterfly Named Evelyn’ (54:44) . In this new interview, Ida Gallia (aka Evelyn Stewart) reflects on her career as an actress. She talks about her childhood and her relationship with acting, discussing her work in the Italian Westerns of the 1960s and her enjoyment of these ‘epic stories’. She talks in some detail about The Bloodstained Butterfly and her discomfort in filming the love scene that takes place in the picture between her character and Giulio. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Me and Duccio’ (8:22) . Lorella De Luca, Duccio Tessari’s wife, reflects on her husband, their relationship and Tessari’s career in cinema. This interview is in Italian with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Mad Dog Helmut’ (17:32) . In yet another new interview, Helmut Berger discusses his work in this film. He suggests that on revisiting the film prior to the interview, he found it amusing that his character, Giorgia, has barely any dialogue in the film: ‘I walked and walked’, he says. Berger reflects on his love of the piano, which worked its way into his performance as Giorgio, and talks about the actresses with whom he worked in the film. He talks about the suggestions made by some filmmakers that he is a ‘difficult’ actor to work with. He also talks about his relationship with the director Luchino Visconti. The interview is in English.

- Promotional gallery (0:05) . This is a gallery of the film’s promotional artwork.

- Italian trailer (3:14) .

- English trailer (3:14) .

Overall

The Bloodstained Butterfly is an interesting film made during a boom period in the production of thrilling all’italiana films (or gialli all’italiana , if you prefer). Bucking some of the paradigms associated with the more pedestrian ‘whodunnit’-style Italian thrillers, The Bloodstained Butterfly arguably has as much in common with the poliziesco all’italiana as the Italian thrilling /giallo , featuring a heavy focus on police procedure, labwork and even courtroom scenes. The attempts to give these scenes a strong sense of realism through the use of zoom lenses, etc, highlights the similarities between the Italian thrillers of this period and American films noir , especially the semidocumentary films noir , with their emphasis on fatalism and psychosexual elements. This particular film, like many films noir , focuses on a dysfunctional masculinity, and it’s striking how deeply flawed all of male characters in this film are – with the narrative using Giulio in particular to stick a proverbial pin into the stereotypes associated with the machismo associated with Italian males and their curious peccadilloes. The Bloodstained Butterfly is an interesting film made during a boom period in the production of thrilling all’italiana films (or gialli all’italiana , if you prefer). Bucking some of the paradigms associated with the more pedestrian ‘whodunnit’-style Italian thrillers, The Bloodstained Butterfly arguably has as much in common with the poliziesco all’italiana as the Italian thrilling /giallo , featuring a heavy focus on police procedure, labwork and even courtroom scenes. The attempts to give these scenes a strong sense of realism through the use of zoom lenses, etc, highlights the similarities between the Italian thrillers of this period and American films noir , especially the semidocumentary films noir , with their emphasis on fatalism and psychosexual elements. This particular film, like many films noir , focuses on a dysfunctional masculinity, and it’s striking how deeply flawed all of male characters in this film are – with the narrative using Giulio in particular to stick a proverbial pin into the stereotypes associated with the machismo associated with Italian males and their curious peccadilloes.

Arrow’s new release of The Bloodstained Butterfly contains a solid presentation of the film (at least, in the DVD version provided for the purposes of this review) that easily eclipses the film’s previous home video releases. Alongside a strong presentation of the main feature is some truly excellent contextual material – including the almost hour long interview with ‘Evelyn Stewart’ (Ida Galli). For fans of the Italian thrilling /giallo , this is an excellent package that comes with a very strong recommendation.

|