|

The Film

Matinee (Joe Dante, 1993) Matinee (Joe Dante, 1993)

Taking place in Key West, in 1962, Joe Dante’s Matinee (1993) juxtaposes the arrival of William Castle-style filmmaker Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) in the small community with the outbreak of the Cuban missile crisis. Woolsey is in Key West to promote his new film ‘Mant!’, about a man who, through having a dental X-ray into which an ant strays, finds himself gradually transforming into a giant ant. Eager to meet Woolsey is fifteen year old cinephile Gene Loomis (Simon Fenton) who, accompanied by his younger brother Dennis (Jesse Lee), spends much of his free time at the local cinema.

Gene and Dennis’ father is in the US Navy, and when the outbreak of the Cuban missile crisis is announced, he is stationed on a blockade ship. At school, Gene experiences a ‘Duck and Cover’ drill, which is interrupted by the dissenting voice of Sandra (Lisa Jakub), a student who sees the ridiculousness of the exercise (‘If you think it’s going to do any good to put your hands behind your neck when a bomb falls, you’re wrong’). Gene is introduced by his friend Stan (Omri Katz) to Sherry (Kellie Martin). When Sherry arranges a date with Stan, Stan finds himself targeted by Sherry’s dumb, older boyfriend Harvey Starkweather (James Villenaire), who is fresh out of prison.

When Gene encounters Woolsey in Key West, Woolsey displays a warmth to the teenager, taking him under his wing and explaining some of his methodology as a filmmaker and a showman. When, in the build-up to the premiere of ‘Mant!’, Harvey is hired by Woolsey to dress up as the titular ‘Mant’ and operate the Rumble-Rama machine, the stage is set for disaster. Meanwhile, Woolsey feels pressure owing to the presence of studio head Mr Spector (Jesse White) during the screening: depending on how the audience react to the picture, Woolsey could be up for a lucrative contract with a big studio. However, during the screening of ‘Mant!’, Harvey turns the Rumble-Rama device up too high, causing the audience – who fear a nuclear bomb has dropped – to panic; in the ensuing chaos, Gene and Sandra are accidentally locked in the cinema owner’s private nuclear bunker and must find a way to escape. When Gene encounters Woolsey in Key West, Woolsey displays a warmth to the teenager, taking him under his wing and explaining some of his methodology as a filmmaker and a showman. When, in the build-up to the premiere of ‘Mant!’, Harvey is hired by Woolsey to dress up as the titular ‘Mant’ and operate the Rumble-Rama machine, the stage is set for disaster. Meanwhile, Woolsey feels pressure owing to the presence of studio head Mr Spector (Jesse White) during the screening: depending on how the audience react to the picture, Woolsey could be up for a lucrative contract with a big studio. However, during the screening of ‘Mant!’, Harvey turns the Rumble-Rama device up too high, causing the audience – who fear a nuclear bomb has dropped – to panic; in the ensuing chaos, Gene and Sandra are accidentally locked in the cinema owner’s private nuclear bunker and must find a way to escape.

In his films, Joe Dante has demonstrated an ability to construct and carefully manage different diegetic layers, using in both Matinee and Explorers (Dante, 1985) the device of a film-within-the-film: here, in Matinee, there is of course ‘Mant!’; in Explorers, the film-within-the-film is the outer space adventure ‘Starkiller’, the picture playing at the drive-in over which the film’s child protagonists hover in their commandeered UFO. Jonathan Rosenbaum has argued that, to some extent, ‘virtually all of Dante’s movies are about the ethics and ramifications of spectatorship’, and through Woolsey’s justifications for the monster movies he makes (and his suggestions that they offer a form of catharsis for their audience) Matinee explores this theme in a very direct manner (Rosenbaum, 2000: 76). However, because Dante ‘prefers to keep a low profile within the studio system and works without a personal publicist […] many reviewers resist treating him like an auteur’ (ibid.).

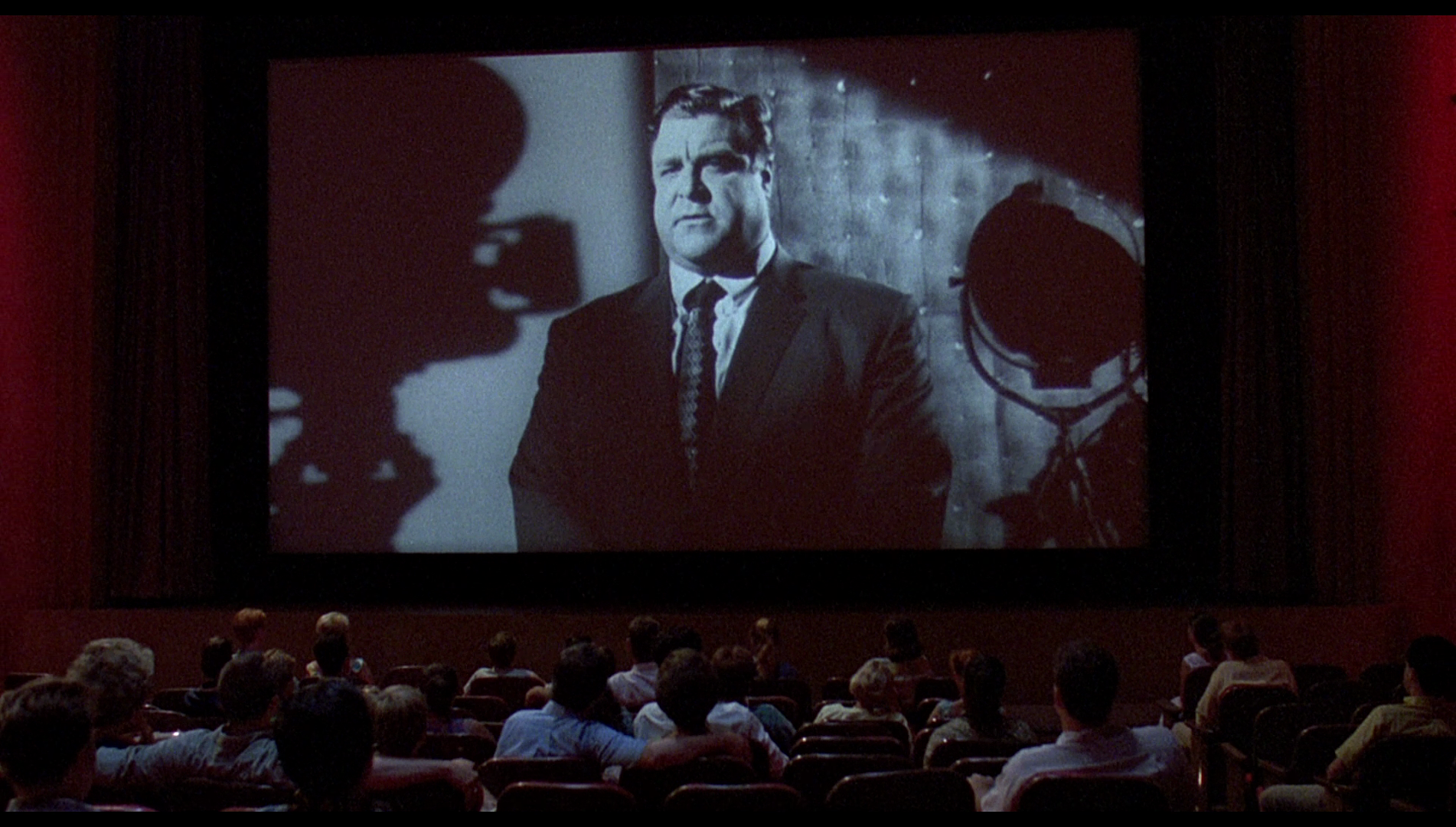

In Matinee, John Goodman plays Lawrence Woolsey, a thinly-veiled caricature of William Castle. In the trailer for ‘Mant!’, Woolsey introduces the film and ‘sells’ it to the audience in a manner of a carnival huckster, highlighting the technological ‘gimmicks’ (Rumble-Rama and Atomo-Vision) associated with it – in the same manner as William Castle and Alfred Hitchcock, both of whom appeared in the trailers for their own pictures. Matinee opens with monochrome footage of nuclear tests, before Woolsey is introduced in silhouette as an onscreen title declares: ‘Presenting the screen’s no. 1 shock expert, Lawrence Woolsey’. Woolsey turns to the camera, addressing the audience: ‘Yes, the atomic bomb is terrible’, he asserts, ‘But more terrible still are the effects of atomic radiation. Hello, I’m Lawrence Woolsey, and I want to warn you of something that could happen, something that does happen in my newest motion picture’. That motion picture is, of course, ‘Mant!’. (One might recollect the trailers for Castle’s The Tingler, 1959, or Hitchcock’s Psycho, 1960.) Foregrounding the theme of spectatorship, and the relationship between filmmaker and audience, this monochrome trailer cuts abruptly to a colour shot of the audience in the Key West cinema in which the trailer is being shown. In Matinee, John Goodman plays Lawrence Woolsey, a thinly-veiled caricature of William Castle. In the trailer for ‘Mant!’, Woolsey introduces the film and ‘sells’ it to the audience in a manner of a carnival huckster, highlighting the technological ‘gimmicks’ (Rumble-Rama and Atomo-Vision) associated with it – in the same manner as William Castle and Alfred Hitchcock, both of whom appeared in the trailers for their own pictures. Matinee opens with monochrome footage of nuclear tests, before Woolsey is introduced in silhouette as an onscreen title declares: ‘Presenting the screen’s no. 1 shock expert, Lawrence Woolsey’. Woolsey turns to the camera, addressing the audience: ‘Yes, the atomic bomb is terrible’, he asserts, ‘But more terrible still are the effects of atomic radiation. Hello, I’m Lawrence Woolsey, and I want to warn you of something that could happen, something that does happen in my newest motion picture’. That motion picture is, of course, ‘Mant!’. (One might recollect the trailers for Castle’s The Tingler, 1959, or Hitchcock’s Psycho, 1960.) Foregrounding the theme of spectatorship, and the relationship between filmmaker and audience, this monochrome trailer cuts abruptly to a colour shot of the audience in the Key West cinema in which the trailer is being shown.

Matinee was the first in a very loose trilogy of films made by Dante that explored the theme of war. The second picture in this series was The Second Civil War (1997), focusing on anti-immigration rhetoric and paranoia; and the final film of the loose trilogy was of course Small Soldiers (1998), in which toy soldiers come to life following the insertion into them of microchips originally intended for missiles, leading the toys to wage a small war in a suburban street. (The Second Civil War is the ‘odd one out’ inasmuch as it bypassed cinemas in America and aired on US television first, though the film received a cinema release in Europe.) Reflecting on the criticisms of Dante’s later picture Small Soldiers (1998), Jonathan Rosenbaum suggests that Small Soldiers ‘doesn’t represent the first time that Joe Dante has been misunderstood, nor, I suspect, will it be the last’ (Rosenbaum, 2000: 76). Rosenbaum points to Matinee as a Dante picture that was misinterpreted by critics, arguing that many critics were so fascinated with exploring the picture’s nostalgic allusions to the cinema of the 1950s and 1960s that they failed to see the parallels between the narrative’s exploration of ‘war fever’ in the context of ‘the Cuban missile crisis and the periodic eviscerations of Baghdad in the early nineties’ (ibid.).

Via the arrival of Woolsey’s picture in Key West, and the juxtaposition of this with the Cuban missile crisis, Matinee fuses the fears of nuclear war during the 1960s with how these fears were mediated by the monster pictures of the era – and by the climax of the picture, both of these become confused owing to the authenticity of Woolsey’s spectacle (and Harvey’s incompetence at controlling the Rumble-Rama machine) and the audience’s perception that ‘the bomb’ has dropped during the screening of ‘Mant!’. As Woolsey suggests, the public’s fears of nuclear war have necessitated a new approach to filmmaking and the development of new methods by which to terrify filmgoers. War, Woolsey says, offers good business for the makers of monster movies: ‘This war stuff spooks ‘em, and then we come in and – POW! – the main event’, Woolsey declares at one point. On the other hand, he argues, during these periods of cultural crisis monster movies offer a form of cathartic relief, giving spectators the opportunity to expel their anxieties – providing them with what is in effect a ‘safety valve’ by which to release their fears. Against the horrors of modern life, filmmakers like Woolsey are forced to develop new technologies that attempt to erode the distinction between audience and film (in the manner of the skeletons that William Castle had fly over the heads of audiences during screenings of his 1959 picture House on Haunted Hill): these are Atomo-Vision and Rumble-Rama, described in the trailer for ‘Mant!’ as ‘the new motion picture miracle that puts you in the picture’. ‘Takes a lot more to scare people these days’, Woolsey tells Gene, ‘Too much competition. They got bombs that can kill half a million people. Nobody’s had a good night’s sleep in years. So you gotta have a gimmick, you know: something a little extra’. Via the arrival of Woolsey’s picture in Key West, and the juxtaposition of this with the Cuban missile crisis, Matinee fuses the fears of nuclear war during the 1960s with how these fears were mediated by the monster pictures of the era – and by the climax of the picture, both of these become confused owing to the authenticity of Woolsey’s spectacle (and Harvey’s incompetence at controlling the Rumble-Rama machine) and the audience’s perception that ‘the bomb’ has dropped during the screening of ‘Mant!’. As Woolsey suggests, the public’s fears of nuclear war have necessitated a new approach to filmmaking and the development of new methods by which to terrify filmgoers. War, Woolsey says, offers good business for the makers of monster movies: ‘This war stuff spooks ‘em, and then we come in and – POW! – the main event’, Woolsey declares at one point. On the other hand, he argues, during these periods of cultural crisis monster movies offer a form of cathartic relief, giving spectators the opportunity to expel their anxieties – providing them with what is in effect a ‘safety valve’ by which to release their fears. Against the horrors of modern life, filmmakers like Woolsey are forced to develop new technologies that attempt to erode the distinction between audience and film (in the manner of the skeletons that William Castle had fly over the heads of audiences during screenings of his 1959 picture House on Haunted Hill): these are Atomo-Vision and Rumble-Rama, described in the trailer for ‘Mant!’ as ‘the new motion picture miracle that puts you in the picture’. ‘Takes a lot more to scare people these days’, Woolsey tells Gene, ‘Too much competition. They got bombs that can kill half a million people. Nobody’s had a good night’s sleep in years. So you gotta have a gimmick, you know: something a little extra’.

Woolsey’s explanation of why horror films appeal to their audiences and why they are culturally valuable artifacts offers a heart-warming affirmation of the importance of monster movies, whilst also – in terms of the rhetoric Woolsey uses – seeming to recall, either intentionally or not, Plato’s allegory of the cave. Woolsey tells Gene the story of a caveman who sees a mammoth and becomes scared by it, running away but simultaneously feeling exhilarated by the experience. Back at the cave, Woolsey says, ‘First thing he does, he makes a drawing of the mammoth. People are coming to see this. Let’s make it good. Let’s make the teeth real long and the eyes real mean. The first monster movie. That’s why I do it. You make the teeth as long as you want, then you kill it off. Everything’s okay. The lights come up. [He sighs.] See, the people come into your cave with a two hundred year old carpet. The guy tears your ticket in half. It’s too late to turn back now [….] Then you come over here to where it’s dark [the auditorium]. There could be anything in there. And you say, “Here I am. What have you got for me?”’.

The boys’ fears about the possibility of nuclear war are tied up in their concern over the wellbeing of their father, who is absent throughout the narrative, stationed on one of the blockade ships. After Gene and Dennis watch on television Kennedy’s address declaring the outbreak of the Cuban missile crisis, Dennis tells his brother at bedtime ‘I’m scared’. The audience might infer that Dennis is afraid of ‘the bomb’ or scared about the wellbeing of the boys’ father. As fears over the threat of nuclear war escalate, a growing sense of anxiety grips the population, to the point that people are shown ‘panic buying’ at the local supermarket. The boys’ fears about the possibility of nuclear war are tied up in their concern over the wellbeing of their father, who is absent throughout the narrative, stationed on one of the blockade ships. After Gene and Dennis watch on television Kennedy’s address declaring the outbreak of the Cuban missile crisis, Dennis tells his brother at bedtime ‘I’m scared’. The audience might infer that Dennis is afraid of ‘the bomb’ or scared about the wellbeing of the boys’ father. As fears over the threat of nuclear war escalate, a growing sense of anxiety grips the population, to the point that people are shown ‘panic buying’ at the local supermarket.

Woolsey is also shown exploiting the moral panics surrounding horror narratives (epitomised by Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comic book diatribe Seduction of the Innocent). He enlists two of his associates, including one whom Gene recognises as the bit-part actor Herb Denning (Dick Miller), to act as ‘moral entrepreneurs, standing outside the cinema showing ‘Mant!’ whilst feigning indignation at the existence of the film. These men masquerade as members of the group Citizens for Decent Entertainment. ‘Have you seen the movie?’, they are asked by a woman in the audience that has gathered around them. ‘I’ve never been down to the sewer’, Herb Denning responds, ‘but I know what’s down there’. Their protest is interrupted by Woolsey himself, who offers a defense of the picture before handing free tickets out to the gathered audience. It’s a clever promotional gimmick, long used by makers of horror films, which is intended to drum up interest in ‘Mant!’ through the fake outrage of the ‘protestors’. As the audience enter the auditorium, Woolsey also has his lover and associate Ruth Corday (Cathy Moriarty) dress as a nurse and ask the audience members to sign a waiver declaring that if they die of fear during the picture, the filmmakers will not be liable. It’s another William Castle-like ploy, but one that impresses visiting studio head Mr Spector. Spector declares during the screening of the film, ‘You see what he’s [Woolsey is] putting back? The showmanship!’

Where Gene’s younger brother Dennis believes that the situation depicted within ‘Mant!’ may conceivably be possible (‘That couldn’t really happen, could it, with the ant?’, Dennis asks Gene), the slightly older Gene has a more worldly point of view – so though he is aware that ‘Mant!’ and its ilk are fictional, he still believes in the magic of cinema. Cinema, it’s suggested, offers Gene something with which to anchor his life: as the son of a man who is in the navy, Gene and his family have spent their time moving from one military base to another. When Gene’s mother asks him why he doesn’t make any friends, he tells her, ‘We moved to a town where everybody’s known each other since nursery school. The kids in town don’t like the kids on the base. Then we’re gonna move again, anyway. So what’s the point [in making friends]?’ Where Gene’s younger brother Dennis believes that the situation depicted within ‘Mant!’ may conceivably be possible (‘That couldn’t really happen, could it, with the ant?’, Dennis asks Gene), the slightly older Gene has a more worldly point of view – so though he is aware that ‘Mant!’ and its ilk are fictional, he still believes in the magic of cinema. Cinema, it’s suggested, offers Gene something with which to anchor his life: as the son of a man who is in the navy, Gene and his family have spent their time moving from one military base to another. When Gene’s mother asks him why he doesn’t make any friends, he tells her, ‘We moved to a town where everybody’s known each other since nursery school. The kids in town don’t like the kids on the base. Then we’re gonna move again, anyway. So what’s the point [in making friends]?’

Sandra’s outburst during the school’s ‘duck and cover’ drill offers a viewpoint which, likely to many of the film’s viewers, articulates modern attitudes towards such futile exercises and, in the context of the era depicted within the film, anticipates the student protests of the 1960s. ‘If you think it’s going to do any good to put your hands behind your neck when a bomb falls, you’re wrong’, she asserts loudly. The way the scene is delivered also suggests parallels between Sandra and Kevin McCarthy’s apparently hysterical outburst (‘They’re here! They’re already here! You’re next!’) in Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Her dissent is criticised by both the staff, who usher her away, and the other students. ‘That girl’s a communist’, one boy declares. Sandra’s parents are unconventional; Sandra is clearly ‘clued in’ about both the ‘red scare’ and the raging debates about Civil Rights which would erupt during the 1960s, and her parents seem to be the only ones in Key West who are keen for their child to watch Woolsey’s new movie. It has been said, by Robert K Musil, that the ‘duck and cover’ drills of the 1950s helped foster the mindset that led to the student protests of the following decade: Musil has argued that ‘In many ways, the styles and explosions of the 1960s were born in those subterranean high-school corridors, where we decided that our elders were unreliable, perhaps even insane’ (Musil, quoted in Matthews, 2007: 134).

Video

Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Matinee is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, running for 98:36 mins. Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Matinee is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, running for 98:36 mins.

The film itself features a mixture of 35mm monochrome photography (for the film-within-a-film ‘Mant!’) and 35mm colour photography. Some of the latter features heavy use of coloured filters. For example, after Gene and Dennis leave the cinema following their viewing of the trailer for ‘Mant!’, a red filter is used over the lens, giving their journey home an otherworldly feel. This is removed when Gene and Dennis’ mother reassures Dennis, ‘It’s not real sweetie’ (in reference to the film they have just watched), the photography in that instant becoming more naturalistic in its palette.

Throughout, the presentation is rich in detail. Most of the film is shot with a strong depth of field (facilitated by the use of lenses with shorter focal lengths that have the aperture ‘stopped down’). The monochrome footage has excellent contrast with good tonality but a very subtle blue tinge to it which may or may not have been intentional on the part of the filmmakers. As noted above, some of the colour photography makes use of coloured filters on the lens of the camera, such as the aforementioned scene in which Gene and Dennis return home after their first visit to the cinema. The use of these filters gives some sequences an otherworldly feel whilst also bumping the contrast (as per the usual effects of putting, say, a red filter over a lens). The footage without these filters features a naturalistic palette which is rich in colour reproduction and, as with the monochrome footage, shows very good contrast. The encode is strong and the picture retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track is clear throughout and, whilst no Rumble-Rama, demonstrates excellent range, being deep and bassy when it’s needed to be. The subtitles are clear and easy to read, whilst also being free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes:

- ‘Bit Parts!: The Joe Dante Players’ (10:06). Dante and some of the actors who have appeared frequently in his films talk about their working relationships. Contributors include Roberto Picardo, Archie Hahn, Belinda Balaski, John Sayles and Dick Miller. Dante reflects on the importance of his early experience of television to his work, and he suggests that by working with the same actors over and over again, he develops a ‘short-hand’ method of communicating. - ‘Bit Parts!: The Joe Dante Players’ (10:06). Dante and some of the actors who have appeared frequently in his films talk about their working relationships. Contributors include Roberto Picardo, Archie Hahn, Belinda Balaski, John Sayles and Dick Miller. Dante reflects on the importance of his early experience of television to his work, and he suggests that by working with the same actors over and over again, he develops a ‘short-hand’ method of communicating.

- ‘Atomo-Vision: Making Matinee’ (8:04). This featurette features input from the film’s cinematographer, John Hora, and its editor, Marshall Harvey. Both participants talk about how they came to be associated with Dante. They discuss Dante’s attention to detail and suggest that though he is known for his careful planning, he is also open to new ideas introduced on the sets of his films.

- ‘Paranoia in Ant Vision’ (31:20). In this interview from 2011, Dante talks about the origins of Matinee and the ways in which the original concept differed from the finished film. He reflects on the development process and how the story was reworked during this period. The difficulties in financing the film are examined in some detail. Dante suggests that the film ‘is the kind of picture that big studios don’t make [….] because they don’t know how to sell them’.

- ‘Mant!’:

-- Foreword by Joe Dante (6:18). Here, Dante introduces the film-within-a-film. Dante suggests that ’Mant!’ ‘captures the era’, even though by 1962 very few films of that type were still being produced. Dante underscores how, in his search for authenticity, he ‘stole dialogue’ from a number of films of the 1950s.

-- ’Mant!’ (16:09). Here, edited together, the viewer may watch all of the footage shot for the ’Mant!’ sequences.

-- ’Mant!’ trailer (3:31). This is the trailer for ’Mant!’ that is seen at the start of Matinee.

- Original EPK (4:26). This contemporary electronic press kit features clips from the film interspersed with behind the scenes footage and interviews with Dante, Simon Fenton and Cathy Moriarty.

- Behind the scenes footage (8:21). Gathered from Dante’s personal archive, this footage showing the shooting of the film is shot on video and timestamped, and it shows Dante working with the actors to elicit their performances.

- Deleted and extended scenes (2:27). More footage of Dennis watching television is included here, alongside an extension of Gene’s conversation with his mother. A scene of Stan and Sherry chatting outside school is present, as is a new scene featuring Gene sitting in the cinema with Sandra, who asks him to fetch some popcorn for her. A very brief scene of Gene and Dennis conversing at bedtime is included, alongside some very brief scene fragments.

- Trailer (1:55).

Overall

Matinee is a warm picture that, in many ways, is about the film audience’s love for monster movies and, more generally, horror films. Throughout the picture, Dante maintains an adolescent worldview that is filled with wonder. ‘You know, it’s kind of hard to believe you’re a grown-up’, Gene tells Woolsey at the end of the film. ‘It’s a hustle, kid’, Woolsey responds, ‘Grown-ups are making it up as they go along, just like you do. You remember that, you’ll be fine’. Matinee is a warm picture that, in many ways, is about the film audience’s love for monster movies and, more generally, horror films. Throughout the picture, Dante maintains an adolescent worldview that is filled with wonder. ‘You know, it’s kind of hard to believe you’re a grown-up’, Gene tells Woolsey at the end of the film. ‘It’s a hustle, kid’, Woolsey responds, ‘Grown-ups are making it up as they go along, just like you do. You remember that, you’ll be fine’.

Arrow’s presentation of the film is fine, a clear upgrade from the previously-available DVDs. The solid presentation of the main feature is accompanied by some very good contextual material, in the form of interviews with Dante and some of the other participants in the production. It’s definitely a pleasing release of a film that has acquired a strong following.

References

Matthews, Melvin E, 2007: Hostile Aliens, Hollywood and Today’s News: 1950s Science-Fiction Films and 9/11. New York: Algora Publishing

Rosenbaum, Jonathan, 2000: Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See. London: Wallflower Press

|