|

|

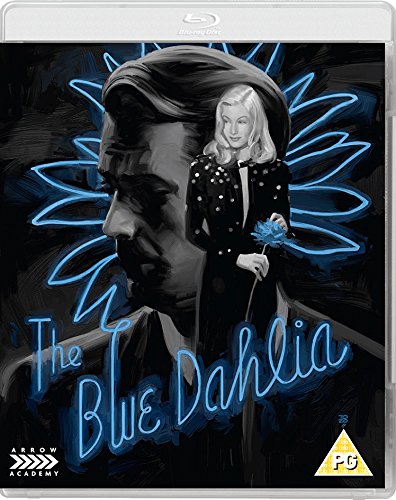

Blue Dahlia (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (6th October 2016). |

|

The Film

The Blue Dahlia (George Marshall, 1946) The Blue Dahlia (George Marshall, 1946)

Written by Raymond Chandler, George Marshall’s 1946 film noir The Blue Dahlia represented the third pairing of Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake, following This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and The Glass Key (Stuart Heisler, 1942; also recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here). To some extent, The Blue Dahlie was intended to ride on the coattails of the success of Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), which had been co-written by Chandler (with Wilder). The popularity of that film led to Paramount placing Chandler under contract, and he wrote the screenplay for The Blue Dahlia using as the basis for its narrative an outline for a novel that he had begun to write but which he had never completed. (As part of his contract with Paramount, Chandler also contributed to the writing of Irving Pichel’s drama And Now Tomorrow, 1944, which also starred Alan Ladd, and Lewis Allen’s 1945 thriller The Unseen.) The Blue Dahlia begins with the arrival in Los Angeles of three war veterans, Johnny Morrison (Alan Ladd) and his friends Buzz Wanchek (William Bendix) and George Copeland (Hugh Beaumont). The three drink together in a bar. Buzz, who in combat sustained an injury to his skull, leaving him with a metal plate in his head and a tendency to display moments of shell shock-like disconnectedness with the world around him, gets into an argument with a soldier over the volume of the juke box in the bar.  Johnny pays a visit to his wife Helen (Doris Dowling), who lives in a bungalow which is within a gated community. Helen is throwing a party; Johnny is greeted with much less than a hero’s welcome, Helen acting coldly towards him. Johnny becomes aware that in his absence, Helen has been conducting an affair with one of the party guests, Eddie Harwood (Howard Da Silva), the owner of the Blue Dahlia nightclub. Johnny pays a visit to his wife Helen (Doris Dowling), who lives in a bungalow which is within a gated community. Helen is throwing a party; Johnny is greeted with much less than a hero’s welcome, Helen acting coldly towards him. Johnny becomes aware that in his absence, Helen has been conducting an affair with one of the party guests, Eddie Harwood (Howard Da Silva), the owner of the Blue Dahlia nightclub.

Alone, Helen spitefully tells Johnny that their son Dicky, whom Helen had previously claimed died after contracting diphtheria, actually died in a car accident caused by Helen as, drunk, she was heading to a party. Johnny takes out his service pistol and suggests he should kill Helen (‘That’s what I ought to do. But you’re not worth it’), leaving the gun in the bungalow. After leaving Helen, Johnny telephones Buzz and George. Concerned, Buzz decides to try to find his friend and drops by the complex in which Helen’s bungalow is located. Buzz bumps into Helen at the bar, unaware that she is Johnny’s wife, and the pair flirt with one another. Meanwhile, Eddie talks with Leo (Don Costello), the manager of the Blue Dahlia. Leo reflects on his own wife, Joyce (Veronica Lake), who has left him, and he decides to call Helen and end their affair. By chance, Johnny encounters Joyce when she offers him a lift in her car. Of course, Johnny is unaware of Joyce’s identity, and the pair hit it off. When Helen’s maid discovers the corpse of Helen, who has apparently been shot to death in her bungalow, Johnny immediately becomes the prime suspect in the investigation that is headed by Captain Hendrickson (Tom Powers). Whilst Johnny finds himself on the run, the ‘house dick’ of the complex in which Helen lived, the elderly ‘Dad’ Newell (Will Wright), approaches Eddie and insinuates he saw Eddie murder Helen. Elsewhere in the city, Joyce and Johnny come to a similar conclusion, and Johnny’s belief that Eddie is the culprit is compounded when Johnny finds among his things a note from Helen which tells him that Eddie’s real name is Bauer, and that Eddie is wanted by the police in New Jersey.  In much literature about film noir, the importance of the Second World War and the cultural fallout that followed it is emphasised as a defining paradigm of the form. If films noir didn’t explore the trauma of the war directly, in the form of narratives about veterans who return home either to commit acts of violence owing to their traumatised state (for example, Fred Zinnemann’s 1948 Act of Violence, in which Robert Ryan and Van Heflin play former POWs who are pitted against one another) or who return home simply to find that things aren’t what they once were (in John Cromwell’s 1947 Dead Reckoning, Humphrey Bogart returns home from the war and finds his AWOL friend dead), the films were exploring the cultural impact of the war in less direct ways. Film noir historian Foster Hirsch has suggested that the ‘full-fledged noir dramas in the immediate postwar period’ may be taken as ‘a sign of contemporary disillusionment and malaise’ (Hirsch, quoted in Early, 2003: 148). Elaborating on Hirsch’s claim, Emmett Early has highlighted the fact that twenty films noir made during the ‘classic’ period of the form featured plots that focused on war veterans, contending that film noir ‘was already established and waiting for the Second World War veteran to stumble into it like a dark alley’ (ibid.: 107). Quoting Hirsch again, Early argues that ‘When he surfaces in noir, the returning soldier has the disconnectedness of an ex-con; he seems both amnesiac and somnambulistic. The crime dramas absorb the soldiers into the noir world rather than focusing directly on such problems of the immediate postwar situation as demobilization’ (ibid.: 108). In much literature about film noir, the importance of the Second World War and the cultural fallout that followed it is emphasised as a defining paradigm of the form. If films noir didn’t explore the trauma of the war directly, in the form of narratives about veterans who return home either to commit acts of violence owing to their traumatised state (for example, Fred Zinnemann’s 1948 Act of Violence, in which Robert Ryan and Van Heflin play former POWs who are pitted against one another) or who return home simply to find that things aren’t what they once were (in John Cromwell’s 1947 Dead Reckoning, Humphrey Bogart returns home from the war and finds his AWOL friend dead), the films were exploring the cultural impact of the war in less direct ways. Film noir historian Foster Hirsch has suggested that the ‘full-fledged noir dramas in the immediate postwar period’ may be taken as ‘a sign of contemporary disillusionment and malaise’ (Hirsch, quoted in Early, 2003: 148). Elaborating on Hirsch’s claim, Emmett Early has highlighted the fact that twenty films noir made during the ‘classic’ period of the form featured plots that focused on war veterans, contending that film noir ‘was already established and waiting for the Second World War veteran to stumble into it like a dark alley’ (ibid.: 107). Quoting Hirsch again, Early argues that ‘When he surfaces in noir, the returning soldier has the disconnectedness of an ex-con; he seems both amnesiac and somnambulistic. The crime dramas absorb the soldiers into the noir world rather than focusing directly on such problems of the immediate postwar situation as demobilization’ (ibid.: 108).

The Blue Dahlia focuses explicitly on the return of war veterans to their home communities. In the film’s opening sequence, Johnny, Buzz and George are shown arriving at a bar. They buy drinks there. A uniformed soldier is playing music on a jukebox. The volume of the music disturbs Buzz, who demonstrates for the first time in the film one of his moments of escalating psychological confusion. The sequences exploring Buzz’s internal torment, caused by the injury he sustained in the war but also more deep-rooted and psychological than that physical explanation might suggest (ie, in terms of what, today, would be described as PTSD), are incredibly effective. The camera brings us close to Buzz’s face, whilst on the audio track sound is used expressionistically to communicate Buzz’s mental confusion: we hear a rumbling sound that, as the film progresses, we come to realise is Buzz’s rising sense of panic and anger that, but for the intervention of his pals George and Johnny, will inevitably lead to violence. In the bar, Buzz argues with the soldier before they make their peace. The bartender tells Buzz and his friends, ‘If you guys want to fight so bad, why don’t you put on a uniform?’ ‘What’d you figure I had on when I got this?’, Buzz responds, showing the bartender the scar on his skull which indicates the metal plate in his head. With this gesture, the men in the bar set aside their differences and demonstrate a level of mutual respect owing to their wartime service. The Blue Dahlia focuses explicitly on the return of war veterans to their home communities. In the film’s opening sequence, Johnny, Buzz and George are shown arriving at a bar. They buy drinks there. A uniformed soldier is playing music on a jukebox. The volume of the music disturbs Buzz, who demonstrates for the first time in the film one of his moments of escalating psychological confusion. The sequences exploring Buzz’s internal torment, caused by the injury he sustained in the war but also more deep-rooted and psychological than that physical explanation might suggest (ie, in terms of what, today, would be described as PTSD), are incredibly effective. The camera brings us close to Buzz’s face, whilst on the audio track sound is used expressionistically to communicate Buzz’s mental confusion: we hear a rumbling sound that, as the film progresses, we come to realise is Buzz’s rising sense of panic and anger that, but for the intervention of his pals George and Johnny, will inevitably lead to violence. In the bar, Buzz argues with the soldier before they make their peace. The bartender tells Buzz and his friends, ‘If you guys want to fight so bad, why don’t you put on a uniform?’ ‘What’d you figure I had on when I got this?’, Buzz responds, showing the bartender the scar on his skull which indicates the metal plate in his head. With this gesture, the men in the bar set aside their differences and demonstrate a level of mutual respect owing to their wartime service.

The experiences of these three men are contrasted with those men who have stayed at home: Eddie Harwood, who has avoided serving in the war owing to his criminal record, and ‘Dad’ Newell, the elderly house dick at the estate on which Helen lives whose age has excluded him from serving during the war. The film acknowledges in its opening sequence that life for those returning from the war is different to what they experienced prior to their service. When, in the bar, Buzz and George ask Johnny about his wife and son, Johnny is elusive – the first hint that his son has passed away. ‘Well, here’s to what was’, Johnny toasts, his words looking back to the past rather than focusing on the present. Much of the rest of the film involves Johnny coming to terms with the changes that have taken place whilst he has been away: Helen’s infidelity (her affairs with various men, the latest of which is of course Eddie Harwood) and the death of his young son, which in letters Helen told Johnny was owing to diphtheria but which Johnny soon discovers was caused by a car accident that came about because of Helen’s party lifestyle.  Whilst Johnny has been away, Helen has been conducting affairs with various men, it seems, and has positioned herself as somewhat of a ‘goodtime girl’, cuckolding Johnny in his absence. When Johnny arrives at her bungalow, he is greeted by another woman, in a party dress, who finds it hysterically funny when Johnny introduces himself as Helen’s husband, as if the idea of Helen being involved in a matrimonial relationship is utterly ridiculous. Soon, it becomes apparent that Eddie is Helen’s current lover. ‘I think I’d better breeze’, he says after spotting Johnny. ‘Why?’, Helen asks naively. ‘Isn’t it obvious why?’, Eddie responds. Turning her attention towards Johnny, Helen addresses the other guests, telling them ‘My husband wants to be alone with me. He probably wants to beat me up’, before adding, in reference to her husband’s status as a returning war veteran, ‘You’re a hero. A hero can get away with anything’. (Of course, as the narrative progresses and the police pursue Johnny, suspecting him of the murder of Helen, this assertion is proven to be utterly false.) After the other guests have left, Johnny wanders into Helen’s bedroom and looks lovingly at a photograph of his dead son Dicky. Bitterly, Helen suggests that her status as a ‘goodtime girl’ both caused the death of Dicky and, ironically, has been facilitated by the death of the child: ‘We lived in a five room house and I’d do the laundry’, she asserts, referring to her life with Johnny prior to the war, ‘I never went anywhere because I had a kid to look after. I don’t have a kid to look after anymore’. Whilst Johnny has been away, Helen has been conducting affairs with various men, it seems, and has positioned herself as somewhat of a ‘goodtime girl’, cuckolding Johnny in his absence. When Johnny arrives at her bungalow, he is greeted by another woman, in a party dress, who finds it hysterically funny when Johnny introduces himself as Helen’s husband, as if the idea of Helen being involved in a matrimonial relationship is utterly ridiculous. Soon, it becomes apparent that Eddie is Helen’s current lover. ‘I think I’d better breeze’, he says after spotting Johnny. ‘Why?’, Helen asks naively. ‘Isn’t it obvious why?’, Eddie responds. Turning her attention towards Johnny, Helen addresses the other guests, telling them ‘My husband wants to be alone with me. He probably wants to beat me up’, before adding, in reference to her husband’s status as a returning war veteran, ‘You’re a hero. A hero can get away with anything’. (Of course, as the narrative progresses and the police pursue Johnny, suspecting him of the murder of Helen, this assertion is proven to be utterly false.) After the other guests have left, Johnny wanders into Helen’s bedroom and looks lovingly at a photograph of his dead son Dicky. Bitterly, Helen suggests that her status as a ‘goodtime girl’ both caused the death of Dicky and, ironically, has been facilitated by the death of the child: ‘We lived in a five room house and I’d do the laundry’, she asserts, referring to her life with Johnny prior to the war, ‘I never went anywhere because I had a kid to look after. I don’t have a kid to look after anymore’.

The film’s examination of gender politics is typical of films noir, with the shrewish and unfaithful Helen contrasted with the warm and supportive Joyce. Much as Johnny and Eddie are the polar opposite of one another (Johnny, the righteous war veteran, contrasted with the sleazy Eddie, who has avoided serving in the war), the film juxtaposes Helen, the bitter brunette, with Joyce, the sweet blonde. ‘I told you she was poison’, Leo tells Eddie in reference to Helen, ‘They’re all poison, sooner or later’. When Johnny arrives home, he finds his wife to be spiteful, bitter and, most of all, independent: ‘You’re not paying for my drinks’, she tells him angrily. Meanwhile, Johnny accepts a lift from Joyce, whose status as the estranged wife of Eddie is unknown to Johnny. At the end of the ride, Johnny and Joyce part ways. ‘It’s tough to say goodbye’, Johnny says. ‘Why is it? You’ve never seen me before’, Joyce asks. ‘Every guy’s seen you before’, Johnny comments in reference to Joyce’s embodiment of an archetype of femininity, ‘The trick is to find you’.  The film is part of a distinguished canon of films noir that are set in Los Angeles. Alastair Phillips compares The Blue Dahlia with Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), suggesting that both films paint ‘a portrait of Los Angeles marked by criminal ghosts and the seedy glamour of the leisured classes’ (Phillips, 2009: 32). The film emphasises the sense of isolation and anonymity that is engendered within the metropolis. In several scenes, Johnny encounters police officers who have his description, but the police officers fail to recognise Johnny as the suspect for whom they are searching. Part way through the picture, Johnny talks with Joyce, and Joyce hints at this theme of anonymity when she observes: ‘Takes a lot of lights to make a city, doesn’t it?’ The film is part of a distinguished canon of films noir that are set in Los Angeles. Alastair Phillips compares The Blue Dahlia with Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), suggesting that both films paint ‘a portrait of Los Angeles marked by criminal ghosts and the seedy glamour of the leisured classes’ (Phillips, 2009: 32). The film emphasises the sense of isolation and anonymity that is engendered within the metropolis. In several scenes, Johnny encounters police officers who have his description, but the police officers fail to recognise Johnny as the suspect for whom they are searching. Part way through the picture, Johnny talks with Joyce, and Joyce hints at this theme of anonymity when she observes: ‘Takes a lot of lights to make a city, doesn’t it?’

Chandler’s original script for the film, based on an incomplete novel, was written in 1944 and rushed into production, only to be halted when Chandler struggled to write the second half of the story, discovering that it didn’t have a satisfactory ending (see Naremore, 1998: 108). When pressed by Paramount’s general manager, Chandler agreed to attempt to finish the script – but only on a bizarre condition, that he write it whilst under the influence of whisky. For eight days, Chandler worked on the script, drinking bourbon almost constantly and reputedly not eating solid food (ibid.). James Naremore highlights the fact that the completed script begins and ends with mention of bourbon (ibid.). As it stands, the climax feels rushed, the revelation of the identity of Helen’s killer coming out of left-field. This was reputedly owing to the intervention of the Navy Department, who felt that having Buzz as Helen’s killer – Chandler’s original intention for the resolution – was too risqué given the context of the film’s production; this censorial intervention, James Naremore suggests, may perhaps have been the true reason for Chandler’s desire to complete the script whilst under the influence of booze (ibid.). Chandler’s original desire to have Buzz as the killer of Helen added a sense of complexity that was stripped away by the Navy Department’s desire that the finger of guilt be pointed at another character: in Chandler’s preferred version of the story, the returning veteran Buzz would, owing to the trauma he suffered in combat, murder Helen accidentally before blacking-out the memory of this incident and legitimately striving to help Johnny identify Helen’s killer and bring him to justice. As Naremore says, ‘[t]he loss of Buzz as the killer […] turns The Blue Dahlia into the sort of entertainment Chandler spent his entire career attacking: a classic detective story, bringing all the suspects together in a single room and dramatically revealing one of them as the guilty party’ (ibid.: 111).  Speaking of the Navy Department’s intervention in the script, Chandler later said in interview, ‘What the Navy Department did to the story was a little thing like making me change the murderer and hence make a routine whodunit out of a fairly original idea’ (Chandler, quoted in ibid.: 110). Regardless, the script was completed in 1945, the Breen Office also demanding some changes be made prior to production. The sticking points for the Breen’s Office were the scenes of violence, which were muted in the completed picture, and the script’s less-than-favourable representation of the police (ibid.: 111). The Breen Office ensured that the film followed the paradigms of Hollywood pictures which ‘avoid ambiguities, providing a neat balance sheet of rewards and punishments’ (ibid.: 113). Speaking of the Navy Department’s intervention in the script, Chandler later said in interview, ‘What the Navy Department did to the story was a little thing like making me change the murderer and hence make a routine whodunit out of a fairly original idea’ (Chandler, quoted in ibid.: 110). Regardless, the script was completed in 1945, the Breen Office also demanding some changes be made prior to production. The sticking points for the Breen’s Office were the scenes of violence, which were muted in the completed picture, and the script’s less-than-favourable representation of the police (ibid.: 111). The Breen Office ensured that the film followed the paradigms of Hollywood pictures which ‘avoid ambiguities, providing a neat balance sheet of rewards and punishments’ (ibid.: 113).

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, with a running tome of 99:59 mins. The film is uncut. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation takes up approximately 27Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, with a running tome of 99:59 mins. The film is uncut. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation takes up approximately 27Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc.

The 35mm monochrome photography is represented well here. There is some print damage here and there, but it’s minor and consists of little more than white flecks and specks suggesting debris on the negative. Detail is strong but in comparison with Arrow’s presentation of The Glass Key, a film of a similar vintage (and presumably shot under similar conditions with similar lenses), their presentation of The Blue Dahlia is a little softer and has slightly less definition. I hasten to add that this is not a displeasing presentation, by any stretch of the imagination, but just that it’s a little less impressive than Arrow’s presentation of The Glass Key. Certainly, in terms of detail it’s a huge step forwards from the previously available DVD releases of this film. Contrast is good, with defined midtones. Blacks are sometimes ‘crushed’, which perhaps suggests that, in combination with what’s noted above, the source for this presentation was a step or two farther away from the original negative than the source for Arrow’s presentation of The Glass Key. This seems to be confirmed by the grain structure of the image, which is a little more coarse than that of Arrow’s The Glass Key – again suggesting a source removed a step or two farther away from the negative. (Information on the exact source for this presentation seems a little scarce, but I’d hazard a guess, based on the qualities outlined above, that it may have been a print.) The film’s photography features some interesting compositions, many of them remarkably similar to the compositions in early 20th Century crime photography Arthur ‘Weegee’ Fellig’s work, published in the tabloids but gathered together in Weegee’s 1945 book Naked City. Fellig’s photography has been an acknowledged influence on the visual style of many films noir, his images of crime and deprivation in New York City establishing the visual paradigms that would be emulated in the films noir of the 1940s and 1950s and used as a photographic short-hand for gritty realism. In this film, one particular shot, presumably taken from a fire escape, looks down upon Johnny as he’s hauled away by two fake coppers. All we see of the men are the tops of their hats and the sidewalk’s sharp angles. The composition seems deliberately reminiscent of one of Weegee’s most famous images, ‘Human Head Cake Box Murder’ (from c.1940), in which Weegee – shooting surreptitiously from a fire escape – captured a top-down image of detectives and a photographer gathered at the feet of an ‘El’ train support, gazing upon the almost surreal image of a severed human head stuffed into a cake box.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is clear throughout with good range: it’s not ‘showy’, but music, sound effects and dialogue are represented well. What’s noticeable about the sound design of the film is the use of near-constant ‘good-time’ nightclub music as a counterpoint to the bitterness of the main drama. The audio track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are clear and easy to read, and they are also free from errors.

Extras

Extras on this disc include:  - A selected scene audio commentary. Here, Frank Krutnik, film noir historian and the author of the volume In a Lonely Street, comments on two specific sequences from the film: the opening bar sequence, which foregrounds the film’s overriding theme of war veterans returning home, and Johnny’s visit to Helen’s bungalow in the midst of the party she is throwing. Krutnik’s comments explore the symbolism within these two sequences, and given the insight and attention to detail here, it’s a shame there isn’t a feature length commentary from Krutnik. - A selected scene audio commentary. Here, Frank Krutnik, film noir historian and the author of the volume In a Lonely Street, comments on two specific sequences from the film: the opening bar sequence, which foregrounds the film’s overriding theme of war veterans returning home, and Johnny’s visit to Helen’s bungalow in the midst of the party she is throwing. Krutnik’s comments explore the symbolism within these two sequences, and given the insight and attention to detail here, it’s a shame there isn’t a feature length commentary from Krutnik.

- ‘Small Boy, Tough Guy’ (29:22). This interview with film noir historian Frank Krutnik focuses on Ladd’s career and reflects on The Blue Dahlia’s place within it, and within the canon of film noir as a whole. - The 1949 radio dramatisation (28:56), starring Ladd and Lake. - The film’s trailer (2:30). - A stills gallery (6 pages).

Overall

Chandler reputedly referred to Ladd as a ‘small boy’s idea of a tough guy’ (Chandler, quoted in Naremore, 1998: 107). Ladd was never as convincing as a film noir anti-hero as actors like Robert Mitchum or, of course, Bogart. He seems a little out of place here, arguably too clean cut for the class differences delineated in the script between Johnny and Eddie Harwood to stand out for the film’s audience. Nevertheless, he’s good here, but he’s surrounded by some even better players: the standout performance in the film arguably comes from William Bendix as the traumatised Buzz. The psychological trauma of the war, which is arguably the film’s major theme, is represented through a visual signifier: the scar on the scalp of Buzz. Buzz’s moments of disassociation are depicted in a very effective manner, using techniques one might associated with experimental cinema rather than a film noir of the classic period. Chandler reputedly referred to Ladd as a ‘small boy’s idea of a tough guy’ (Chandler, quoted in Naremore, 1998: 107). Ladd was never as convincing as a film noir anti-hero as actors like Robert Mitchum or, of course, Bogart. He seems a little out of place here, arguably too clean cut for the class differences delineated in the script between Johnny and Eddie Harwood to stand out for the film’s audience. Nevertheless, he’s good here, but he’s surrounded by some even better players: the standout performance in the film arguably comes from William Bendix as the traumatised Buzz. The psychological trauma of the war, which is arguably the film’s major theme, is represented through a visual signifier: the scar on the scalp of Buzz. Buzz’s moments of disassociation are depicted in a very effective manner, using techniques one might associated with experimental cinema rather than a film noir of the classic period.

Chandler’s script moves along at a fair old clip, and typical of Chandler’s writing, the film contains some excellent hardboiled dialogue. When Johnny confronts Eddie near to the film’s climax, Eddie threatens to call the police. ‘Why don’t you?’, Johnny asks. ‘I’m not that kind of rat’, Eddie responds. ‘What kind are you?’, Johnny queries. ‘You think you’re a pretty tough boy, don’t you?’, Eddie taunts Johnny. ‘Tough enough to find out who killed my wife’, Johnny tells him. The sense of compromise in the denouement, dictated by the demands of the Navy Department and the Breen Office, will be felt by even the most casual viewers – but the reveal of the Helen’s murderer as someone other than Buzz is given depth by Chandler in the dialogue. (The real killer of Helen is given a phenomenal line right at the end of the picture, which goes some way towards redeeming the compromised resolution to the narrative’s primary enigma.) With regards this Blu-ray release, the presentation of the main feature, whilst not as pleasing as Arrow’s release of The Glass Key, is a head and shoulders improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases. (I’d also suggest that of the two Ladd films Arrow have released previously, this is the better one owing to the qualities of Chandler’s writing and the film’s expressionistic representation of Buzz’s internal trauma.) This pleasing main presentation is accompanied by some excellent contextual material, the interview with Krutnik going a great way towards setting the scene for the production of the picture and exploring its relationship with both the canon of film noir and Ladd’s career as an actor. In all, this is an excellent package, and represents another Arrow Academy release which should be essential to any film noir fans collection. References: Early, Emmett, 2003: The War Veteran in Film. London: McFarland and Company Naremore, James, 1998: More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts. University of California Press Phillips, Alastair, 2009: ‘The Blue Dahlia’. In: Hillier, Jim & Phillips, Alastair (eds), 2009: 100 Film Noirs. London: Palgrave Macmillan: 32-3

|

|||||

|