|

|

Vamp (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th October 2016). |

|

The Film

Vamp (Richard Wenk, 1986) Vamp (Richard Wenk, 1986)

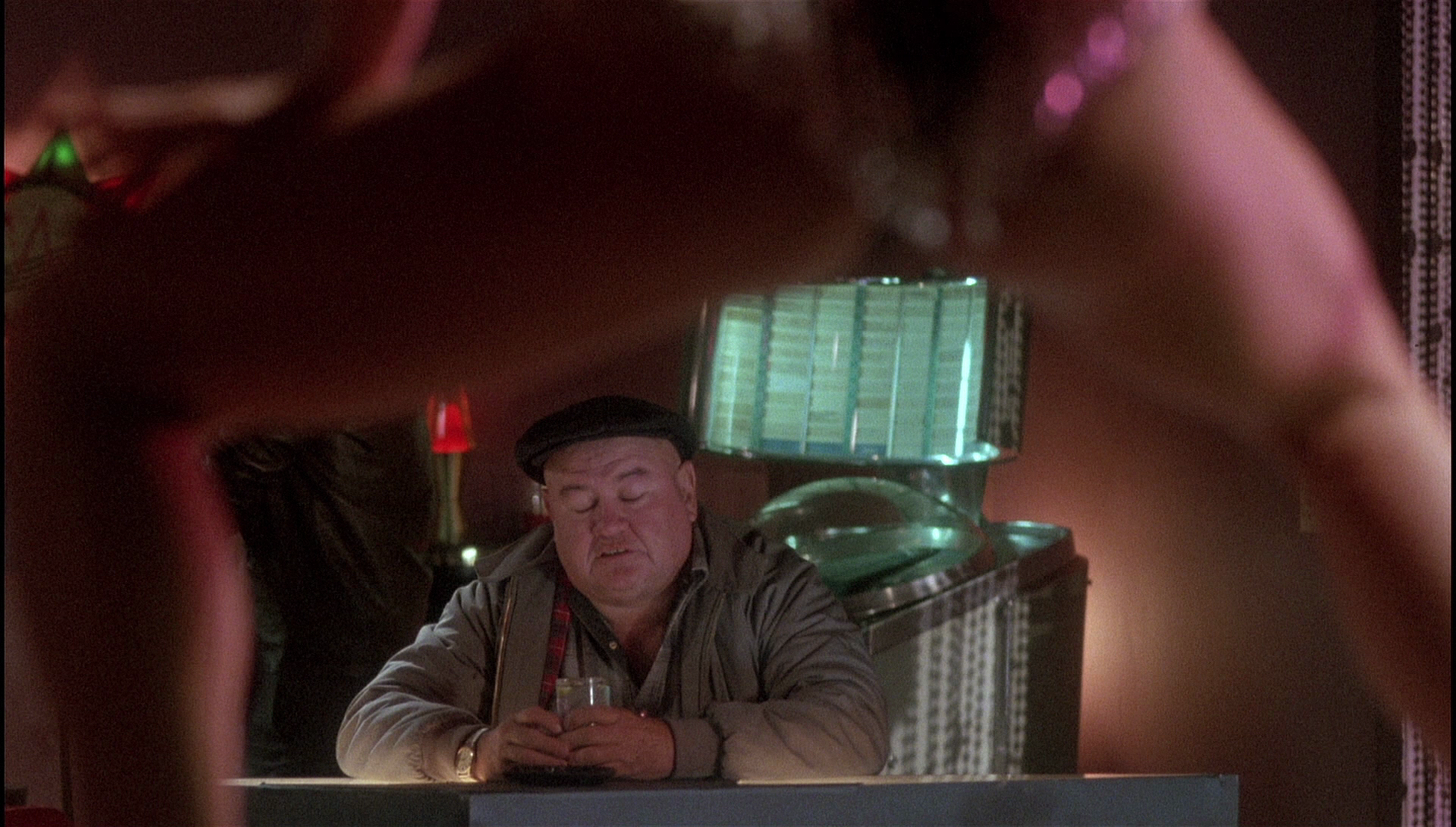

In the mid-1980s, the American vampire film underwent something of a Renaissance, with a slew of films exploring – and destabilising – the mythology that had been associated with cinematic vampires since Tod Browning’s 1931 Dracula. Since the 1960s, with pictures such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and George A Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), the American horror film had gradually shucked off the trappings of the Universal horror pictures of the 1930s, whose popularity had cemented the major paradigms of the American horror film for decades to come; the horror films of the 1960s and after eschewed the exotic period settings of the Universal horror pictures (and, later, Hammer’s horror films) in favour of bringing horror into the present day, transplanting creatures such as vampires from their distant Transylvanian castles to modern-day USA. The feature debut of its director Richard Wenk, who had previously directed an accomplished short film ‘Dracula Bites the Big Apple’ (1979, included on this Blu-ray release as an extra feature) and would in the 2000s become a writer of Hollywood action films such as Antoine Fuqua’s current remake of The Magnificent Seven (2016) and the forthcoming Jack Reacher: Never Go Back (Edward Zwick, 2016), Vamp begins with a scene intended to allude to the Gothic archetypes associated with traditional vampire films. A Latin chorus is heard on the soundtrack and we are presented with what seems to be the interior of a church. A hooded man approaches two young men who, it seems, are about to be executed in a bizarre ritual. However, things go awry and it’s soon revealed that this is nothing more than an initiation into a fraternity. The two young men, AJ (Robert Rusler) and Keith (Chris Makepeace), are given a reprieve and offered an alternative way to join the fraternity: they must score a stripper for the frat house party. AJ and Keith enlist the help of their nerdy, but wealthy and car-owning, friend Duncan (Gedde Watanabe), and the three companions head into the city at night with the intention of visiting the After Dark Club.  In the city, the three friends decided to stop at a café. There, they find themselves threatened by a street gang led by albino punk Snow (Billy Drago). However, AJ bests Snow in a fight, and the trio move on to the After Dark Club where they are welcomed by the club’s owner Vic (Sandy Baron). Vic introduces the acts, culminating in the club’s standout performance by Katrina (Grace Jones). Impressed with Katrina’s show, AJ visits her backstage. Wordlessly, Katrina seems to seduce AJ, who doesn’t resist until Katrina’s shape changes and she reveals herself to be a feral vampire who tears into AJ’s flesh. In the city, the three friends decided to stop at a café. There, they find themselves threatened by a street gang led by albino punk Snow (Billy Drago). However, AJ bests Snow in a fight, and the trio move on to the After Dark Club where they are welcomed by the club’s owner Vic (Sandy Baron). Vic introduces the acts, culminating in the club’s standout performance by Katrina (Grace Jones). Impressed with Katrina’s show, AJ visits her backstage. Wordlessly, Katrina seems to seduce AJ, who doesn’t resist until Katrina’s shape changes and she reveals herself to be a feral vampire who tears into AJ’s flesh.

Worried about AJ when he doesn’t return, Keith enlists the help of one of the club’s hostesses, Amaretto (Dedee Pfeiffer), who insists that she knows Keith even though Keith cannot remember her. As Duncan continues to flirt with the waitresses (‘What time do you get off?’, he asks one of them; ‘Two-thirty’, she replies; ‘Can I watch?’, Duncan queries sleazily before laughing uncontrollably), Keith and Amaretto visit a nearby hotel in the search for AJ. Keith and Amaretto become separated, however, and after encountering Snow’s street gang in an alleyway, Keith seeks refuge in the sewers. Emerging from the sewers, Keith finds AJ’s exsanguinated corpse in a dumpster. However, entering the club again he finds AJ in front of him – unaware that AJ is a reanimated corpse, a vampire. Cornered by Vic and the other vampires in the club, Keith manages to escape owing to the intervention of Amaretto – and Keith, Amaretto and Duncan flee in the latter’s car. However, when Duncan, who is sitting in the back seat of the car, reveals himself to be a vampire too, Keith crashes the vehicle, which explodes in a ball of flame, killing Duncan. Keith and Amaretto are left to flee through the streets of the city, until they come face to face one last time with Katrina and her army of vampires.  The figure of the vampire had already been ‘updated’ in revisionist horror films of the late 1960s and 1970s such as A Taste of Blood (H G Lewis, 1967), The Body Beneath (Andy Milligan, 1970), Blacula (William Crain, 1972), Count Yorga, Vampire (Bob Kelljan, 1970) and The Night Stalker (John Llewellyn Moxey, 1972). Modern-day vampires even made their way into television series such as Starsky & Hutch, a 1976 episode of which featured the titular detectives (Paul Michael Glaser and David Soul, respectively) stalking a vampire (John Saxon) through the city. Originally, in the case of films like A Taste of Blood and The Body Beneath the present-day settings of these films were as much a product of economic necessity as anything else: the makers of Count Yorga, Vampire reputedly decided to set their film in the present-day because the available budget didn’t permit them to construct a convincing period setting (see our review of Arrow’s recent Blu-ray release of the Count Yorga films here). However, as the 1970s rolled on the makers of such films found ways to make the present-day settings integral to their narratives (or vice versa): George A Romero’s Martin (1977), perhaps the finest American vampire film of the latter half of the Twentieth Century, uses its modern setting to represent vampirism ambiguously. Throughout the film, Romero juxtaposes the actions of the film’s protagonist (Martin, who the film suggests may either be an immortal vampire or simply a disturbed youth) in the present day with Martin’s visions of himself in a period setting, with the result that the audience is never sure whether these are genuine analepses/flashbacks indicating that Martin has lived for centuries – or simply the fantasies of a troubled young mind. The figure of the vampire had already been ‘updated’ in revisionist horror films of the late 1960s and 1970s such as A Taste of Blood (H G Lewis, 1967), The Body Beneath (Andy Milligan, 1970), Blacula (William Crain, 1972), Count Yorga, Vampire (Bob Kelljan, 1970) and The Night Stalker (John Llewellyn Moxey, 1972). Modern-day vampires even made their way into television series such as Starsky & Hutch, a 1976 episode of which featured the titular detectives (Paul Michael Glaser and David Soul, respectively) stalking a vampire (John Saxon) through the city. Originally, in the case of films like A Taste of Blood and The Body Beneath the present-day settings of these films were as much a product of economic necessity as anything else: the makers of Count Yorga, Vampire reputedly decided to set their film in the present-day because the available budget didn’t permit them to construct a convincing period setting (see our review of Arrow’s recent Blu-ray release of the Count Yorga films here). However, as the 1970s rolled on the makers of such films found ways to make the present-day settings integral to their narratives (or vice versa): George A Romero’s Martin (1977), perhaps the finest American vampire film of the latter half of the Twentieth Century, uses its modern setting to represent vampirism ambiguously. Throughout the film, Romero juxtaposes the actions of the film’s protagonist (Martin, who the film suggests may either be an immortal vampire or simply a disturbed youth) in the present day with Martin’s visions of himself in a period setting, with the result that the audience is never sure whether these are genuine analepses/flashbacks indicating that Martin has lived for centuries – or simply the fantasies of a troubled young mind.

All of these films represented a firm step away from the paradigms of the Universal horror films or the Hammer Gothics – though admittedly, Hammer tried to ape this formula, somewhat disastrously, with their own Dracula AD 1972 (Alan Gibson, 1972), in which Dracula is resurrected at the fag end of the Swinging London era. In the 1980s, the American vampire film consolidated its focus on the present day, before in the 1990s becoming once again briefly fascinated with the past via the juxtaposition of past and present in Neil Jordan’s 1994 adaptation of Anne Rice’s novel Interview with a Vampire. 1980s vampire pictures made in the US featured an explicit focus on youth culture – predominantly, as Ken Gelder has argued, ‘(upwardly) mobile white youth, on the whole’ (Gelder, 1994: 103). Pictures such as The Lost Boys (Joel Schumacher, 1987) and Near Dark (Kathryn Bigelow, 1987) ‘introduced a rock’n’roll soundtrack, developed the connections between special effects, speed and travel, fine-tuned the vampiric puns, and had their vampires getting around in gangs, showing off their leather and their hardware’ (ibid.).  Given the tendency for vampires of the 1980s to move around in gangs and wear the visual signifiers of youth culture (leather jackets, denims, etc), one might easily expect Snow and his gang, whom AJ and Keith confront soon after they venture into the inner city at night, to be revealed to be the film’s vampires; but this isn’t the case, and towards the climax of the film Snow’s street gang are cornered by a group of unlikely vampires (the elderly, the homeless) and, notably, set upon by a little girl vampire who overcomes Snow. One of the things that’s interesting about Vamp is its representation of the vampires themselves: the silent, ancient Katrina turns into a feral beast who rips at the flesh of her victims rather than simply puncturing their necks with extended canines in the manner of Bela Lugosi’s Dracula. In fact, Katrina seems more like the revenants of European folklore, visual similarities (especially in her teeth) connecting her with Max Schreck’s vampire in F W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) or, to give a more contemporaneous example, the feral creatures in Lamberto Bava’s Demoni (Demons, 1985). When Keith is reunited with AJ, who unbeknownst to Keith has been transformed into a vampire himself, the dialogue suggests AJ is as much zombie as vampire, AJ’s pleas to Keith and his claims to hunger recalling zombified Freddy’s (Thom Mathews) cry that ‘I don’t care, darlin’, because I love you, and you’ve got to let me eat your brains!’ in Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead (1985). ‘We can’t let you leave’, AJ tells Keith, ‘“Home” is a million miles away from me now. “Home” is another planet. I’m a fuckin’ zombie now. I mean, look at me [….] I love you Keith, but all I can see right now is food. And I’m starvin’. You carry my next meal around in your veins. They got me. They got me real good’. AJ continues, addressing the lore surrounding vampires directly: ‘Do I look real bad?’, he asks, gazing into a mirror where, of course, he has no reflection, ‘You know, it’s just like the movies. You can’t see yourself [….] It does work, you know. The fire, the wooden stakes, the sunlight’. AJ commits suicide by throwing himself onto a wooden stake, but returns later in the film and comments in an offhand manner that the stake onto which he threw himself was actually formica – and thus didn’t have the desired effect. However, AJ’s comments set the scene for Keith’s final confrontation with Katrina, which climaxes in a moment that alludes quite strongly to the denouement of Terence Fisher’s The Horror of Dracula (1957). Given the tendency for vampires of the 1980s to move around in gangs and wear the visual signifiers of youth culture (leather jackets, denims, etc), one might easily expect Snow and his gang, whom AJ and Keith confront soon after they venture into the inner city at night, to be revealed to be the film’s vampires; but this isn’t the case, and towards the climax of the film Snow’s street gang are cornered by a group of unlikely vampires (the elderly, the homeless) and, notably, set upon by a little girl vampire who overcomes Snow. One of the things that’s interesting about Vamp is its representation of the vampires themselves: the silent, ancient Katrina turns into a feral beast who rips at the flesh of her victims rather than simply puncturing their necks with extended canines in the manner of Bela Lugosi’s Dracula. In fact, Katrina seems more like the revenants of European folklore, visual similarities (especially in her teeth) connecting her with Max Schreck’s vampire in F W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) or, to give a more contemporaneous example, the feral creatures in Lamberto Bava’s Demoni (Demons, 1985). When Keith is reunited with AJ, who unbeknownst to Keith has been transformed into a vampire himself, the dialogue suggests AJ is as much zombie as vampire, AJ’s pleas to Keith and his claims to hunger recalling zombified Freddy’s (Thom Mathews) cry that ‘I don’t care, darlin’, because I love you, and you’ve got to let me eat your brains!’ in Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead (1985). ‘We can’t let you leave’, AJ tells Keith, ‘“Home” is a million miles away from me now. “Home” is another planet. I’m a fuckin’ zombie now. I mean, look at me [….] I love you Keith, but all I can see right now is food. And I’m starvin’. You carry my next meal around in your veins. They got me. They got me real good’. AJ continues, addressing the lore surrounding vampires directly: ‘Do I look real bad?’, he asks, gazing into a mirror where, of course, he has no reflection, ‘You know, it’s just like the movies. You can’t see yourself [….] It does work, you know. The fire, the wooden stakes, the sunlight’. AJ commits suicide by throwing himself onto a wooden stake, but returns later in the film and comments in an offhand manner that the stake onto which he threw himself was actually formica – and thus didn’t have the desired effect. However, AJ’s comments set the scene for Keith’s final confrontation with Katrina, which climaxes in a moment that alludes quite strongly to the denouement of Terence Fisher’s The Horror of Dracula (1957).

In its focus on youth culture, Vamp begins as a John Hughes-style teen comedy, opening with a frat house initiation and the dilemma faced by the film’s young protagonists (to find a way of scoring a stripper for the frat house party). Keith, AJ and Duncan’s journey into the heart of the city at night recalls other 1980s/early 1990s pictures focusing on a flight through a threatening and often surreal nighttime cityscape (John Landis’ Into the Night, 1985; Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, 1985; Walter Hill’s The Warriors, 1979; Stephen Hopkins’ Judgment Night, 1993). This is foregrounded when, arriving in the inner city at night, one of the group comments, ‘You get the feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore’: the journey into the inner city acts like the portal in a portal fantasy such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Duncan’s car taking the young men down the proverbial rabbit hole. ‘Yeah, I definitely think it’s after dark now’, AJ comments when he and his friends encounter Snow’s street gang in the café. In its focus on youth culture, Vamp begins as a John Hughes-style teen comedy, opening with a frat house initiation and the dilemma faced by the film’s young protagonists (to find a way of scoring a stripper for the frat house party). Keith, AJ and Duncan’s journey into the heart of the city at night recalls other 1980s/early 1990s pictures focusing on a flight through a threatening and often surreal nighttime cityscape (John Landis’ Into the Night, 1985; Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, 1985; Walter Hill’s The Warriors, 1979; Stephen Hopkins’ Judgment Night, 1993). This is foregrounded when, arriving in the inner city at night, one of the group comments, ‘You get the feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore’: the journey into the inner city acts like the portal in a portal fantasy such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Duncan’s car taking the young men down the proverbial rabbit hole. ‘Yeah, I definitely think it’s after dark now’, AJ comments when he and his friends encounter Snow’s street gang in the café.

With the movement to the inner city the film gradually shifts paradigms from the teen comedy into a horror picture, in which the boys are terrorised by the albino hoodlum Snow and his street gang, before evolving into a fully-fledged vampire film once Katrina reveals her true identity about a third of a way through the picture’s running time – when Keith, AJ and Duncan visit the strip club and watch Katrina’s performance prior to AJ being killed by the vampiric Katrina when he visits her backstage room. In the use of a strip club as the key location for the film’s major paradigmatic shift, Vamp may have had some impact on Quentin Tarantino’s script for Robert Rodriguez’s later From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), which begins as a crime caper but evolves into a vampire film once the Gecko brothers (Tarantino and George Clooney) find themselves locked in the Titty Twister strip club at night and witness the showstopping striptease of Salma Hayek (From Dusk Till Dawn’s answer to Katrina’s dance in Vamp).  Shot in liquid pinks and greens, the strip club is a den of iniquity in which the fairly well-to-do young men (AJ, Duncan and Keith) stand out. Owner and master of ceremony’s Vic’s patter is pure showman: he introduces one of the dancers as ‘Builder of major erections – our construction engineer, Hard Hatted Hannah’. The sequence in the strip club climaxes with Katrina’s appearance on stage: her face and body painted white, and with a bizarre pink wig, Katrina cuts a striking figure. She poises herself next to a headless mannequin, her movements predatory and animalistic. Her performance climaxes with her riding the mannequin, grinding her crotch into the area where its face would be, if it were to have one, in a not-so-subtle suggestion of cunnilingus. It’s a show that is as much frightening as it is erotic. Shot in liquid pinks and greens, the strip club is a den of iniquity in which the fairly well-to-do young men (AJ, Duncan and Keith) stand out. Owner and master of ceremony’s Vic’s patter is pure showman: he introduces one of the dancers as ‘Builder of major erections – our construction engineer, Hard Hatted Hannah’. The sequence in the strip club climaxes with Katrina’s appearance on stage: her face and body painted white, and with a bizarre pink wig, Katrina cuts a striking figure. She poises herself next to a headless mannequin, her movements predatory and animalistic. Her performance climaxes with her riding the mannequin, grinding her crotch into the area where its face would be, if it were to have one, in a not-so-subtle suggestion of cunnilingus. It’s a show that is as much frightening as it is erotic.

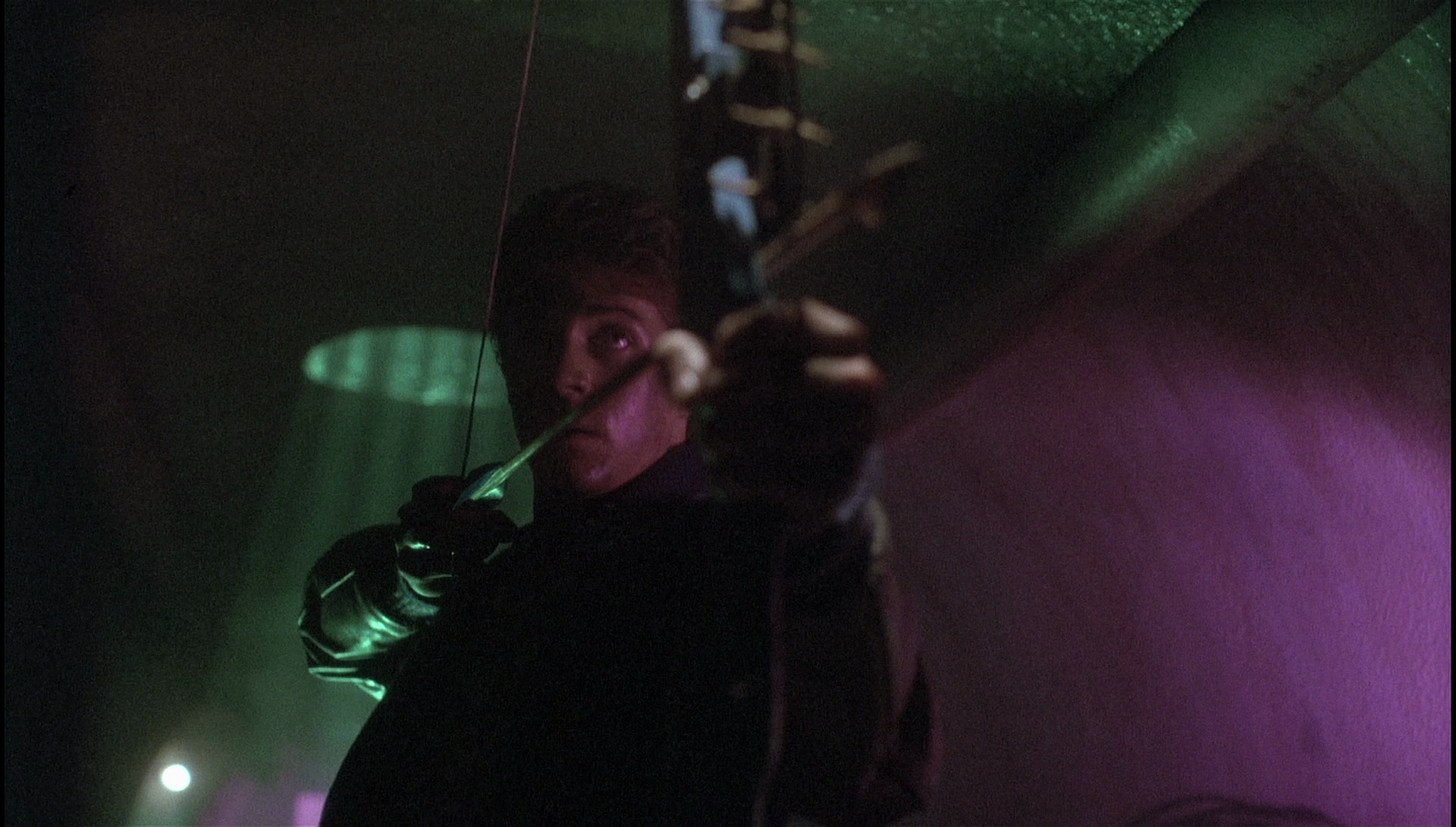

The film’s title (‘Vamp’) has a double meaning: as an abbreviation of the word ‘vampire’, and also as a term used to denote a femme fatale. Katrina is as much a femme fatale as anything else, her performance in the club acting as a prelude to her seduction, and subsequent murder, of AJ. Throughout much of the rest of the film, Amaretto’s role is called into question: is she genuinely helping Keith to escape from the nightmares of the strip club, or is she too a ‘vamp’ – a femme fatale? Wenk seems to suggest the latter in a sequence in which, fleeing from the vampires through the city, Keith and Amaretto break into a pawn shop to steal items they may use as weapons against their attackers. They are interrupted by a vampire. Keith dispatches this vampire using a long bow he has found in the pawn shop. He and Amaretto flee from the scene, and as they pass out the doorway the camera pans up to reveal the security mirror above the door. Keith’s reflection is shown, but Amaretto is not there: it’s a fleeting glimpse, and the viewer is left with the question as to whether Amaretto does not have a reflection (which would suggest she is a vampire), or did she simply pass through the doorway too quickly for us to see her in the mirror?  Vamp foregrounds its difference from the archetypes of the traditional Gothic vampire picture in its opening sequence, with knowingly references the paradigms of most vampire pictures made before the 1970s. The film begins with the depiction of a bizarre ritual in what seems to be a period setting. A chant in Latin is presented on the soundtrack whilst, onscreen, we see a hooded figure approach two bound men; the setting seems to be a church. ‘Welcome to your worst nightmare’, the hooded figure asserts. The two young men, we believe, are about to be hanged. However, the audio is scrambled and someone yells ‘cut’: the reason for the scrambled audio is soon revealed to be a malfunctioning tape deck and the film soon reveals that the location is nothing more than a set in a frat house: the film has swiftly destabilised our initial perception of this sequence by revealing it to be an initiation ceremony for the fraternity the film’s protagonists are aiming to join, the frat boys’ co-opting of the paradigms of Gothic fiction revealing how much of a cliché that imagery had become. (In this sense, and via its later use of performance-as-ritual in the scenes set in the strip club, Vamp seems to owe something of a debt to the films of Jess Franco, which would often feature Gothic iconography as part of decadent nightclub performances; this is a particular trait of Franco’s Succubus, 1968, and Exorcismes et messes noires, 1973.) Vamp foregrounds its difference from the archetypes of the traditional Gothic vampire picture in its opening sequence, with knowingly references the paradigms of most vampire pictures made before the 1970s. The film begins with the depiction of a bizarre ritual in what seems to be a period setting. A chant in Latin is presented on the soundtrack whilst, onscreen, we see a hooded figure approach two bound men; the setting seems to be a church. ‘Welcome to your worst nightmare’, the hooded figure asserts. The two young men, we believe, are about to be hanged. However, the audio is scrambled and someone yells ‘cut’: the reason for the scrambled audio is soon revealed to be a malfunctioning tape deck and the film soon reveals that the location is nothing more than a set in a frat house: the film has swiftly destabilised our initial perception of this sequence by revealing it to be an initiation ceremony for the fraternity the film’s protagonists are aiming to join, the frat boys’ co-opting of the paradigms of Gothic fiction revealing how much of a cliché that imagery had become. (In this sense, and via its later use of performance-as-ritual in the scenes set in the strip club, Vamp seems to owe something of a debt to the films of Jess Franco, which would often feature Gothic iconography as part of decadent nightclub performances; this is a particular trait of Franco’s Succubus, 1968, and Exorcismes et messes noires, 1973.)

Video

Vamp is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio; the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up about 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, running for 94:01 mins. Vamp is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio; the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up about 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, running for 94:01 mins.

Arrow have released this film on Blu-ray previously, in 2011. That release was in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio and lost a very slight sliver of information at the top and bottom of the image, in comparison with this presentation. Both presentations seem to be based on the same source, with little to differentiate them other than the fact that this more recent release seems a tad brighter. Like Arrow’s previous release, this is a solid presentation of the film. The 35mm colour photography is presented here with good colour reproduction – giving the sequences featuring vivid primary colour lighting (reds and greens, principally) a bold appearance. A number of scenes (eg, some of the performances in the After Dark Club) feature diffused lighting, and these moments are handled nicely here. There’s a good level of detail present throughout the film, and contrast levels are evenly-balanced, with strong midtones and rich shadows. Finally, the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film owing to a strong encode.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track with accompanying optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track displays good range, evidenced from the opening orchestral score onwards. The subtitles are free from errors and easy to read.

Extras

The principal difference between Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Vamp and their older HD release of the same title is in the extras package. This new release adds a new retrospective documentary whilst at the same time dropping some of the extra features that were included in the older release (chiefly, a commentary track featuring Robert Rusler and critic Calum Waddell). The principal difference between Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Vamp and their older HD release of the same title is in the extras package. This new release adds a new retrospective documentary whilst at the same time dropping some of the extra features that were included in the older release (chiefly, a commentary track featuring Robert Rusler and critic Calum Waddell).

This new release of the film contains: - ‘One of Those Nights: The Making of Vamp’ (44:30). This new documentary features input from Wenk, director of photography Elliot Davis, and actors Robert Rusler, Chris Makepeace, Dedee Pfeiffer, Gedde Watanabe and Billy Drago. Wenk reflects on the origins of the story ‘about strippers, college kids and vampires’. All of the participants reflect on the film’s production and seem to hold it in high regard. Rusler suggests that Wenk was an ‘innnovator […] in horror films that had humour behind it [sic]’. - Rehearsal Footage (6:41). This behind the scenes footage, shot on videotape, shows the actors rehearsing for their roles. - ‘Dracula Bites the Big Apple’ (22:03). Here, the viewer may watch Richard Wenk’s 1979 short film, a witty take on the Dracula mythology that has some striking similarities with the later Vamp. - Blooper Reel (6:14). - TV Spots (3:44). - Trailer 1 (1:26). - Trailer 2 (1:58). - Image Gallery.

Overall

An entertaining vampire picture, Vamp fits neatly into the paradigms of 1980s vampire pictures. The film’s odd mixture of John Hughes-style teen comedy and lurid, comic book-esque vampire action makes it seem very much of the time period in which it was made. My first exposure to the film was via its broadcast on BBC2’s ‘Moviedrome’ in 1991; I was lukewarm about the picture then but it’s grown in my estimation since. An entertaining vampire picture, Vamp fits neatly into the paradigms of 1980s vampire pictures. The film’s odd mixture of John Hughes-style teen comedy and lurid, comic book-esque vampire action makes it seem very much of the time period in which it was made. My first exposure to the film was via its broadcast on BBC2’s ‘Moviedrome’ in 1991; I was lukewarm about the picture then but it’s grown in my estimation since.

This Blu-ray presentation is pretty much the same as Arrow’s previous HD release of the same title: the aspect ratio is opened up slightly, featuring a little more information at top and bottom of the frame, and the image is slightly brighter, but it’s essentially the same transfer and clearly based on the same source. This rerelease drops the commentary (with Robert Rusler and Callum Waddell) and some of the interviews from Arrow’s earlier release, replacing these with a new documentary. If you already own Arrow’s previous release, there isn’t much need to pick this rerelease up as well; but otherwise, this release represents a worthwhile purchase for the horror film connoisseur. References: Gelder, Ken, 1994: Reading the Vampire. London: Routledge

|

|||||

|