|

|

Panic in Needle Park (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th October 2016). |

|

The Film

The Panic in Needle Park (Jerry Schatzberg, 1971) The Panic in Needle Park (Jerry Schatzberg, 1971)

The second feature of photographer and director Jerry Schatzberg, The Panic in Needle Park (1971) was also the second screen role of both of its stars, Al Pacino and Kitty Winn. (Pacino’s next role was as Michael Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, 1972.) In 1973, Pacino and Schatzberg would collaborate once again on Scarecrow, an excellent film sadly absent from home video formats in the UK. The Panic in Needle Park begins with Helen (Kitty Winn), an innocent young woman originally from Fort Wayne, returning from a backstreet abortion that has been arranged by her lover, aspiring artist Marco (Raul Julia). The aftereffects of the abortion force Helen to seek treatment at the hospital, whilst Marco leaves the city. However, whilst recuperating she’s visited by Bobby (Al Pacino), a small-time hustler who was Marco’s dealer. When Helen is released from the hospital, she and Bobby move in together; Bobby introduces Helen to his brother Hank (Richard Bright), a burglar (‘It’s my business; it’s what I do’, Hank tells Helen). Through Bobby, Helen meets a number of junkies on the streets and becomes increasingly aware of Bobby’s own addiction to heroin – which renders him impotent and leaves Helen unsatisfied and lonely within their relationship. Eventually, Bobby asks Helen to ‘score for me’. However, when Helen tries to score from Bobby’s named dealer, Freddy (Arnold Williams), she finds herself in the midst of a drugs bust and meets detective Hotchner (Alan Vint). Recognising the difference between Helen and the street junkies with which she is mixing, Hotchner sees Helen as having potential to turn informant.  Helen starts to use heroin quietly, unbeknownst to Bobby. When Bobby proposes marriage to her, he is mocked by his brother Hank, who asks Bobby and Helen what they intend to live on. Helen takes a job as a waitress but is useless at it, and so Bobby accompanies Hank on a number of burglaries; but Bobby is caught and imprisoned. Whilst Bobby is in prison, he is approached with an offer of working as a dealer for Santo (Vic Ramano). He sees this as a shot at the big time. Meanwhile, in Bobby’s absence Helen has begun to turn tricks, even ‘balling’ Bobby’s brother Hank in order to achieve her fix. When Bobby is released from prison and finds out that Helen is working as a prostitute, he is enraged. However, the couple reconcile and Bobby takes the job with Santo, which he believes will promise him ‘thousands and thousands of dollars’ and ‘stuff coming out of our ears’. Meanwhile, Helen becomes increasingly desperate, and Hotchner puts pressure on her to ‘rat’ on Bobby in order for him to get to Santo. Helen starts to use heroin quietly, unbeknownst to Bobby. When Bobby proposes marriage to her, he is mocked by his brother Hank, who asks Bobby and Helen what they intend to live on. Helen takes a job as a waitress but is useless at it, and so Bobby accompanies Hank on a number of burglaries; but Bobby is caught and imprisoned. Whilst Bobby is in prison, he is approached with an offer of working as a dealer for Santo (Vic Ramano). He sees this as a shot at the big time. Meanwhile, in Bobby’s absence Helen has begun to turn tricks, even ‘balling’ Bobby’s brother Hank in order to achieve her fix. When Bobby is released from prison and finds out that Helen is working as a prostitute, he is enraged. However, the couple reconcile and Bobby takes the job with Santo, which he believes will promise him ‘thousands and thousands of dollars’ and ‘stuff coming out of our ears’. Meanwhile, Helen becomes increasingly desperate, and Hotchner puts pressure on her to ‘rat’ on Bobby in order for him to get to Santo.

In 1965, the journalist James Mills published an photo-essay, ‘The Panic in Needle Park’, in Life magazine about the impact on addicts of the 1964 drought of heroin (the titular ‘panic’) caused when 220 pounds of the drug was seized in France. A year later, Mills turned the article into a book, which formed the basis of Schatzberg’s film. (Mills’ other bestselling book, Report to the Commissioner, was also adapted for the screen in the 1970s.) Mills’ account of the ‘panic’ was an embellished non-fiction account that told the story through the eyes of two young people caught up in this scenario: instead of focusing on the major players in the drug trade or the police (in the manner of Robin Moore’s The French Connection, for example, published several years later in 1969), Mills focused instead on the addicts at the bottom of the proverbial food chain. Mills’ protagonists were the 21 year old Bob, a petty thief who over time managed to secure a connection to the Italian-American mob; and his girlfriend, Helen, a prostitute who eventually ‘ratted out’ Bob. The issue was topical: the book was published alongside a number of other books about very similar topics, including Jeremy Larner’s The Addict in the Street (1966) and Yves Kron and Edward Brown’s Mainline to Nowhere: The Making of a Heroin Addict (1965).  Schatzberg’s film adaptation of Mills’ book is strikingly faithful to its source, the documentary-like quality of the narrative finding its corollary in the manner in which the film is shot (see the ‘Video’ section of this review) and the absence of non-diegetic music throughout the picture: for the entire running time of the picture, we only hear sounds that are diegetic, sourced from within the image. Even the opening and closing credits play out over ambient street sounds. Compounding this sense of documentary verisimilitude, the film begins with a title card that defines the film’s title and outlines its subject matter: ‘The intersection at Broadway and 72nd Street on New York’s West Side is officially known as Sherman Square’, the title card tells us, ‘To heroin addicts it’s Needle Park’. Reflecting on the film’s pseudo-documentary aesthetic, William Over has said that with The Panic in Needle Park Schatzberg ‘circumvented the conventional Hollywood aesthetic standards: surface glamour, a parade of easily categorized street characters with comforting appeal, and a fast-paced story and rapid filming style that avoids thoughtful and nuanced exposition. Instead, he chose to develop the characters relatively slowly, presenting their lifestyle choices and family struggles clearly, so that the drug culture of New York City is understood in its complexity and bleakness’ (Over, 2004: 70). Schatzberg’s film adaptation of Mills’ book is strikingly faithful to its source, the documentary-like quality of the narrative finding its corollary in the manner in which the film is shot (see the ‘Video’ section of this review) and the absence of non-diegetic music throughout the picture: for the entire running time of the picture, we only hear sounds that are diegetic, sourced from within the image. Even the opening and closing credits play out over ambient street sounds. Compounding this sense of documentary verisimilitude, the film begins with a title card that defines the film’s title and outlines its subject matter: ‘The intersection at Broadway and 72nd Street on New York’s West Side is officially known as Sherman Square’, the title card tells us, ‘To heroin addicts it’s Needle Park’. Reflecting on the film’s pseudo-documentary aesthetic, William Over has said that with The Panic in Needle Park Schatzberg ‘circumvented the conventional Hollywood aesthetic standards: surface glamour, a parade of easily categorized street characters with comforting appeal, and a fast-paced story and rapid filming style that avoids thoughtful and nuanced exposition. Instead, he chose to develop the characters relatively slowly, presenting their lifestyle choices and family struggles clearly, so that the drug culture of New York City is understood in its complexity and bleakness’ (Over, 2004: 70).

The relationship between Bobby and Helen offers hope to these two young people, especially to Helen, through whom we experience much of the film. When Helen suffers from the aftereffects of the botched abortion she has undergone at the behest of Marco, Bobby offers her kindness and sympathy. This is contrasted with Marco, who acts coldly towards Helen when she tells him that the abortion hurt her and ‘the place was dirty’: ‘Well, sure, baby’, Marco says, ‘It was a “free scrape”, a favour’. However, whatever promise is represented through the early stages of their relationship is dissipated as the narrative progresses. Bobby exhibits his casual approach to criminality soon after Helen is released from the hospital, telling her – by way of courting her – that he has been in prison eight times and stealing a television set from a van as they walk down the street (‘Merry Christmas’, he says, ‘How does it feel to steal something?’). When Helen first meets Bobby’s friends from the street, they ask Bobby, ‘She feeding your arm?’ Quickly, Helen also begins to see the effects of junk on their relationship, Bobby refusing to make love to her when he’s high: ‘I can’t’, he tells her when she makes advances towards him, ‘Not when I’m doing junk, I can’t. When I’m straight’, he promises, ‘Tomorrow, all right, tomorrow’. Repeatedly, from this scene onwards Helen is shown alone at night, her relationship with Bobby defined by her loneliness – until, that is, she decides to shoot heroin and share her partner’s addiction. This comes after Bobby tells Helen to ‘score for me’, and the astute young woman observes, ‘You’re not just asking me to score for you. You’re asking me something else [….] You’re asking me how much I’ll do for you’. Though Bobby tells Helen at one point, ‘I’m a germ. You should split’, Helen tells him that the decision to leave him will be her choice to make: ‘You don’t have to tell me when to go’, she says, ‘Just leave’.  Soon into their relationship, Bobby takes Helen to the flat of Marcie (Marcia Jean Kurtz), a prostitute. There, she sees Mickey (Larry Marshall), who appears desperately ill. She’s told, ‘He’s all right. Mickey boosted a vet’s office and shot himself full of worm medicine’. In the flat, Helen watches as two men, Chico (Kiel Martin) and Whitey (Paul Mace), cook heroin before shooting up. This is the first of the film’s several scenes of explicit drug-taking. These explicit scenes of drug use were presumably the reason for the BBFC’s rejection of the film when it was submitted for classification in 1971. (The film was classified ‘X’ when submitted again a few years later, in 1974.) In 1987, The Panic in Needle Park was submitted to the BBFC for video classification, and the BBFC demanded that 57 seconds be removed from he film – much of this presumably in the scene featuring Whitey and Chico. In close-up, we are shown the needle going into the arm of Chico, his veins damaged from previous hits. Than, after Chico flexes his arm and removes the tourniquet from around it, we are shown a close-up as Chico absorbs the hit before facing the comedown from it. It’s a stark, shockingly realistic scene; in its verisimilitudinous representation of the act of shooting heroin, it may be compared to Larry Clark’s groundbreaking 1971 photography book Tulsa. In that book, Clark, who was at that point in his life a drug addict himself, photographed his friends and acquaintances shooting up (and having sex or playing with guns). Clark’s images were strikingly visceral and graphic in their representation of the activities of drug addicts. As if the visuals weren’t enough, on the audio track, as Chico prepares and shoots the measure of heroin, we hears snatches of a conversation informing us, obliquely, as to what a ‘panic’ is and how terrifying it is for addicts on the street. ‘It’s a real panic, man. Worse than ‘68’, Penny says, ‘The dealers have all gone down to Florida, put their prices up’. ‘I seen guys kicking their habit in the streets’, Chico says, ‘puking in the alleyway’. Soon into their relationship, Bobby takes Helen to the flat of Marcie (Marcia Jean Kurtz), a prostitute. There, she sees Mickey (Larry Marshall), who appears desperately ill. She’s told, ‘He’s all right. Mickey boosted a vet’s office and shot himself full of worm medicine’. In the flat, Helen watches as two men, Chico (Kiel Martin) and Whitey (Paul Mace), cook heroin before shooting up. This is the first of the film’s several scenes of explicit drug-taking. These explicit scenes of drug use were presumably the reason for the BBFC’s rejection of the film when it was submitted for classification in 1971. (The film was classified ‘X’ when submitted again a few years later, in 1974.) In 1987, The Panic in Needle Park was submitted to the BBFC for video classification, and the BBFC demanded that 57 seconds be removed from he film – much of this presumably in the scene featuring Whitey and Chico. In close-up, we are shown the needle going into the arm of Chico, his veins damaged from previous hits. Than, after Chico flexes his arm and removes the tourniquet from around it, we are shown a close-up as Chico absorbs the hit before facing the comedown from it. It’s a stark, shockingly realistic scene; in its verisimilitudinous representation of the act of shooting heroin, it may be compared to Larry Clark’s groundbreaking 1971 photography book Tulsa. In that book, Clark, who was at that point in his life a drug addict himself, photographed his friends and acquaintances shooting up (and having sex or playing with guns). Clark’s images were strikingly visceral and graphic in their representation of the activities of drug addicts. As if the visuals weren’t enough, on the audio track, as Chico prepares and shoots the measure of heroin, we hears snatches of a conversation informing us, obliquely, as to what a ‘panic’ is and how terrifying it is for addicts on the street. ‘It’s a real panic, man. Worse than ‘68’, Penny says, ‘The dealers have all gone down to Florida, put their prices up’. ‘I seen guys kicking their habit in the streets’, Chico says, ‘puking in the alleyway’.

Highlighting for Helen (and the audience) the desperate lengths to which junkies will go to get their fix, Bobby asks Chico, ‘You ever try shootin’ glue?’ With this, Chico turns and asks Helen, ‘You know what the best high of all is?’ ‘What is it?’, Helen queries in response. ‘Death’, Chico tells her. The film returns a number of times to Marcie’s apartment, where her baby is left to scream, unattended, as she and her friends take drugs or Marcie turns tricks. The neglect this child faces is mirrored later in the film when Bobby and Helen take the ferry to Staten Island, where – determined to ‘go straight’ – they buy a puppy. However, returning back home on the ferry Bobby persuades Helen to visit the lavatory where they welch on their vow kick the habit. When they return from the lavatory, Helen is distraught to see the puppy run off the deck of the ferry into the waters below. If the puppy is a symbol of the ‘straight’ life Helen dreams of, free from drugs and crime, its death represents the impossibility of Helen achieving that dream. Highlighting for Helen (and the audience) the desperate lengths to which junkies will go to get their fix, Bobby asks Chico, ‘You ever try shootin’ glue?’ With this, Chico turns and asks Helen, ‘You know what the best high of all is?’ ‘What is it?’, Helen queries in response. ‘Death’, Chico tells her. The film returns a number of times to Marcie’s apartment, where her baby is left to scream, unattended, as she and her friends take drugs or Marcie turns tricks. The neglect this child faces is mirrored later in the film when Bobby and Helen take the ferry to Staten Island, where – determined to ‘go straight’ – they buy a puppy. However, returning back home on the ferry Bobby persuades Helen to visit the lavatory where they welch on their vow kick the habit. When they return from the lavatory, Helen is distraught to see the puppy run off the deck of the ferry into the waters below. If the puppy is a symbol of the ‘straight’ life Helen dreams of, free from drugs and crime, its death represents the impossibility of Helen achieving that dream.

When Helen turns to drugs, there is a sense of inevitability about her trajectory towards becoming a police informant. This is established when she first meets Hotchner, who tells her of the desperation addicts face during a panic – which, he claims, always causes them to ‘rat’ on one another. ‘Bobby never told you about a “panic”, did he?’, Hotchner asks Helen after she has witnessed the arrest of Freddy, ‘This time next month he’ll be ratting for a couple of bags. Everybody rats [….] See, that’s one thing you gotta remember about a junkie is he’ll always rat. Always’. When, towards the end of the film, Hotchner begins to place pressure on Helen to turn informant, he tells her ‘I want Santo’. Helen protests that ‘I’ve never even seen him. I can’t help you’. ‘Then you’re going to have to give me Bobby’, Hotchner says. Helen tries to placate him by offering him some of the street people she knows (Chico, Whitey, etc), but Hotchner dismisses these as small fry. ‘You rat up; you don’t rat down’, Hotchner tells her, in one of the film’s most famous lines, ‘I want Santo […] It’s the game that we’re playing, Helen. I didn’t make the rules’.  In the book Stanley Kubrick at Look Magazine, Philippe Mather connects Schatzberg with Stanley Kubrick and Gordon Parks, two other photographers who turned to film directing (Mather, 2013: 267). Mather suggests that all three were influenced by the paradigms of documentary photography and ‘photomagazine-based codes of realism’ (ibid.). Here, Schatzberg communicates his documentary credentials via the use of telephoto lenses to flatten perspective, shooting the characters from a distance and giving the audience the impression that we are eavesdropping on their conversations and interactions on the street. Likewise, Schatzberg chooses not to use any non-diegetic music; ever sound within the film is sourced within the image itself. Even the opening credits play out without music, and simply accompanied by the sounds of the subway train on which Helen is travelling. (Interestingly, a music score was composed for the film by the composer Ned Rorem, but Schatzberg chose not to use it in the finished film.) Many of the street scenes also seem to have been shot guerilla-style, including a bravura sequence in which Pacino wanders the streets looking for a fix, interacting in a seemingly improvised manner with a number of people on the street who seem to be unaware of the camera’s presence. The film’s narrative is also elliptical, recalling the traditions of observational documentaries which would follow the lives of their subjects at different points, omitting detail simply owing to the impossibility of the camera being present all the time: so when Bobby is arrested after accompany Hank on a heist, we see nothing of his capture or trial, and the film simply cuts from Bobby in the warehouse that he and Hank have broken into to Bobby in the showers of the prison following his conviction for the crime. In the book Stanley Kubrick at Look Magazine, Philippe Mather connects Schatzberg with Stanley Kubrick and Gordon Parks, two other photographers who turned to film directing (Mather, 2013: 267). Mather suggests that all three were influenced by the paradigms of documentary photography and ‘photomagazine-based codes of realism’ (ibid.). Here, Schatzberg communicates his documentary credentials via the use of telephoto lenses to flatten perspective, shooting the characters from a distance and giving the audience the impression that we are eavesdropping on their conversations and interactions on the street. Likewise, Schatzberg chooses not to use any non-diegetic music; ever sound within the film is sourced within the image itself. Even the opening credits play out without music, and simply accompanied by the sounds of the subway train on which Helen is travelling. (Interestingly, a music score was composed for the film by the composer Ned Rorem, but Schatzberg chose not to use it in the finished film.) Many of the street scenes also seem to have been shot guerilla-style, including a bravura sequence in which Pacino wanders the streets looking for a fix, interacting in a seemingly improvised manner with a number of people on the street who seem to be unaware of the camera’s presence. The film’s narrative is also elliptical, recalling the traditions of observational documentaries which would follow the lives of their subjects at different points, omitting detail simply owing to the impossibility of the camera being present all the time: so when Bobby is arrested after accompany Hank on a heist, we see nothing of his capture or trial, and the film simply cuts from Bobby in the warehouse that he and Hank have broken into to Bobby in the showers of the prison following his conviction for the crime.

There are clear class differences between Bobby and Helen, and for much of the film’s running time the audience sees Bobby, his associates and his world through the eyes of the often silent but always watchful Helen. Helen is not from the city, and though very little is said about her background it seems she’s from a moderately comfortable middle-class life. When Helen’s mother gets in touch with her (after Helen has already begun to take heroin), Bobby persuades her to return home for a while in order to score some money from her relatives. (In preparation for this trip, Helen dresses up in a comically exaggerated fashion, putting a clumsy white bow in her hair to show that she’s lost touch with her former life; Bobby thinks she leaves the city to return home, but really she’s gone to turn a trick.) By contrast with Helen, Bobby is resolutely proletarian: streetwise, and with a brother, Hank, who is a not-so-petty thief. As William Over says, despite their differences, both Bobby and Helen ‘find little help from municipal institutions that ignore or brutalize them’ (Over, op cit.: 70).  In its focus on the ways in which people are coaxed into becoming informants, The Panic in Needle Park has something in common with George V Higgins’ novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1970), memorably adapted for the screen by Peter Yates in 1973. Higgins’ novel, and Yates’ film, focus on an aging gunrunner who collaborates with an ATF agent in order to commute his sentence. Eddie, the novel’s protagonist, has no future: his decisions and actions are a desperate attempt to avoid a final, long stretch in prison. Likewise, in The Panic in Needle Park Hotchner senses that Helen is a young woman out of her depth, aware that she is an outsider to the inner city community, and as the film progresses he tightens the screws – watching as she becomes further and further enmeshed in a life of drugs, prostitution and theft – until she has no choice other than to ‘rat’ on Bobby, her lover. In its portrayal of dishonour among thieves, Susan Boyd argues that The Panic in Needle Park ‘links small-time street dealing and heroin addiction with property crime, and it makes clear people addicted to heroin will never go straight. No matter how much we sympathize with them [Bobby and Helen], heroin users are represented as recidivist criminal addicts’ (Boyd, 2008: np). In its focus on the ways in which people are coaxed into becoming informants, The Panic in Needle Park has something in common with George V Higgins’ novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1970), memorably adapted for the screen by Peter Yates in 1973. Higgins’ novel, and Yates’ film, focus on an aging gunrunner who collaborates with an ATF agent in order to commute his sentence. Eddie, the novel’s protagonist, has no future: his decisions and actions are a desperate attempt to avoid a final, long stretch in prison. Likewise, in The Panic in Needle Park Hotchner senses that Helen is a young woman out of her depth, aware that she is an outsider to the inner city community, and as the film progresses he tightens the screws – watching as she becomes further and further enmeshed in a life of drugs, prostitution and theft – until she has no choice other than to ‘rat’ on Bobby, her lover. In its portrayal of dishonour among thieves, Susan Boyd argues that The Panic in Needle Park ‘links small-time street dealing and heroin addiction with property crime, and it makes clear people addicted to heroin will never go straight. No matter how much we sympathize with them [Bobby and Helen], heroin users are represented as recidivist criminal addicts’ (Boyd, 2008: np).

Video

The film is presented here uncut, the cuts imposed by the BBFC to the film’s previous home video releases having been waived. The running time is 109:37. Taking up 29Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is presented here uncut, the cuts imposed by the BBFC to the film’s previous home video releases having been waived. The running time is 109:37. Taking up 29Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

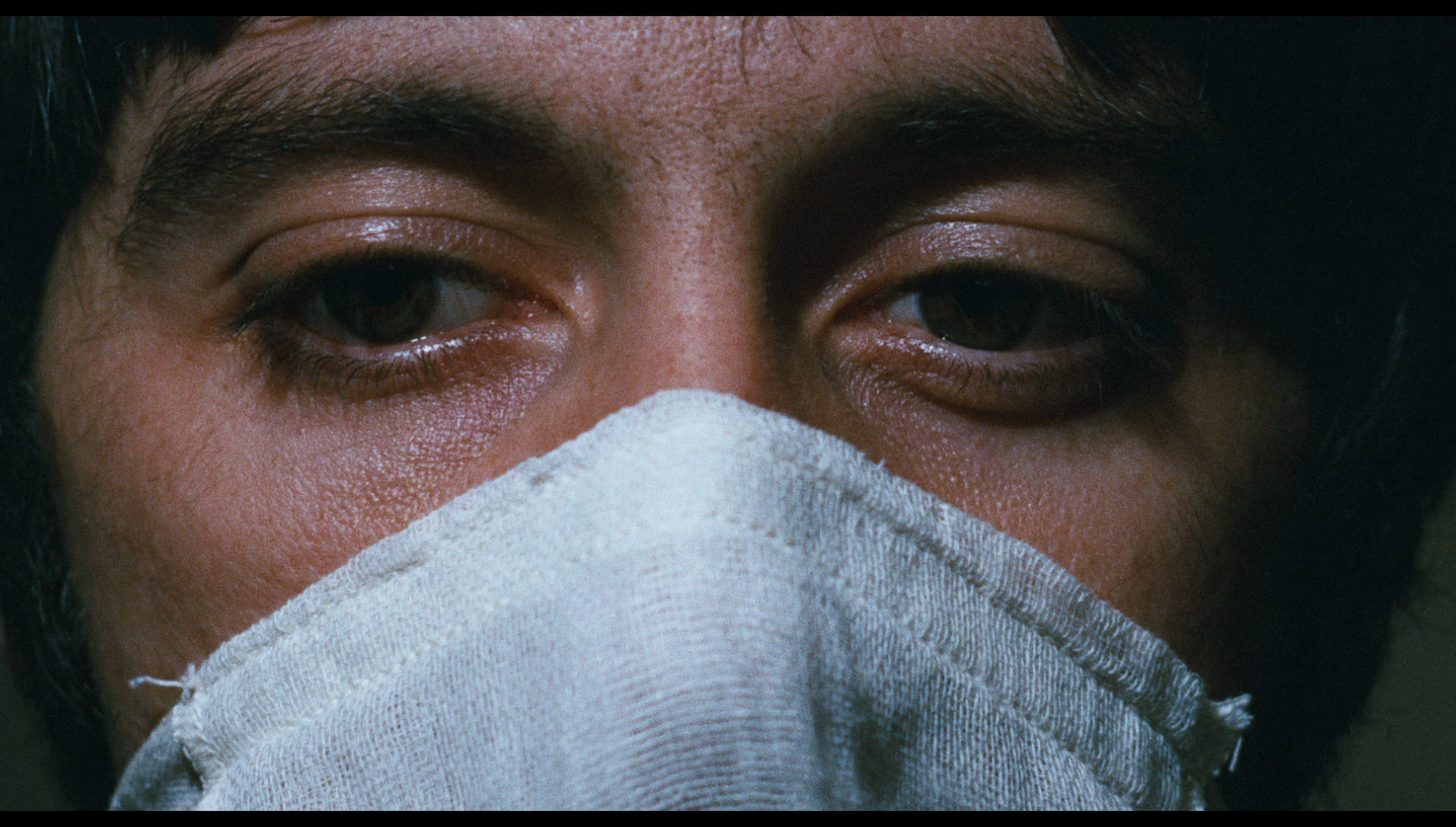

The presentation is extremely rich in detail, something that is evident from the opening close-up of Kitty Winn’s face. Short lenses are used for the interiors, giving a strong depth of field to these indoor sequences which is communicated well in this presentation, whilst the majority of the outdoor scenes are shot with telephoto lenses which flatten perspective and give the film a sense of surveillance and documentary realism. Contrast is beautiful here, with rich midtones and deep blacks. The source is in excellent shape, with little to no damage present. Finally, a superb encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. It’s a stunning presentation of the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of hearing. Although a score for the film had been composed by avant-garde musician Ned Rorem, Schatzberg decided instead to let the film play out without any non-diegetic music whatsoever, reinforcing the sense of documentary realism employed in the photography. The audio track is rich and resonant, with excellent range. The subtitles are easy to read and without errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - A selected scene commentary with director Jerry Schatzberg (21:10). Conducted in 2004, this features Schatzberg commenting on give scenes from the film; Schatzberg speaks in interview in a cinema auditorium whilst we see clips form the film playing on the big screen in the background. The first is the meeting between Bobby and Helen that takes place upon Helen’s release from hospital near the beginning of the picture. Schatzberg talks about Pacino’s tendency to improvise and Bobby’s tendency to ‘challenge’ Helen throughout the film, which is established in this scene. The second scene is the scene in which Bobby plays baseball in the street, which Schatzberg describes as ‘a turning point in the film’ owing to the fact that it’s the scene in which we realise Helen has shot heroin. The third scene is the scene in which Bobby overdoses, and Schatzberg reveals that the actor playing Chico, an ex-addict, helped Schatzberg to stage the scene which was shot with a handheld camera. The fourth scene is the scene in which Bobby is arrested and imprisoned and Helen visits him, the couple holding a conversation in the visiting room via telephone. As Schatzberg says, both Bobby and Helen hold information back from the other party – the fact that Helen is ‘out there hooking’, and the fact that Bobby has been given the chance to work for Santo. The final scene is the scene in which Bobby and Helen buy a puppy, only for it to fall overboard on the ferry home whilst Bobby and Helen are getting their fix in the lavatories. Schatzberg talks about the promise of ‘a normal life’ in this scene and how this is snatched away by their addiction. - ‘Jerry the Photographer’ (17:15). This 2004 interview with Schatzberg focuses on his career as a photographer. Schatzberg reflects on how he came to work as a fashion photographer and discusses his work as a portrait photographer, including working with Bob Dylan for two years and photographing some of the members of Andy Warhol’s ‘Factory’.  - ‘Jerry the Filmmaker’ (21:12). Conducted in the same sitting as the previous interview, this interview with Schatzberg examines his work as a filmmaker. He says that he ‘played around with a 16mm camera’ even though he ‘had no idea I was going to make a film’. He talks about his first film, Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970), with which he became ‘a young director at 40’. This led on to The Panic in Needle Park. Schatzberg initially turned the script down but was persuaded to accept the project by his manager, who was also managing Pacino at the time. He discusses The Panic in Needle Park in detail, reflecting on the picture which he calls ‘a very honest film, a “real” film’. He reflects on the importance of editing, saying ‘You can change a whole performance in editing, or save a performance’. - ‘Jerry the Filmmaker’ (21:12). Conducted in the same sitting as the previous interview, this interview with Schatzberg examines his work as a filmmaker. He says that he ‘played around with a 16mm camera’ even though he ‘had no idea I was going to make a film’. He talks about his first film, Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970), with which he became ‘a young director at 40’. This led on to The Panic in Needle Park. Schatzberg initially turned the script down but was persuaded to accept the project by his manager, who was also managing Pacino at the time. He discusses The Panic in Needle Park in detail, reflecting on the picture which he calls ‘a very honest film, a “real” film’. He reflects on the importance of editing, saying ‘You can change a whole performance in editing, or save a performance’.

- ‘Al and Jerry’ (9:14). Again conducted in 2004, in this interview Schatzberg reflects on working with Pacino at an early stage in the actor’s illustrious screen career. Schatzberg suggests that ‘the best actors come out of the theatre’ and ‘once they’ve got that basic training’ they can ‘do anything’. - ‘Jerry in Cannes’ (5:51). In another piece from 2004, Schatzberg talks about the reception The Panic in Needle Park received when shown at the Cannes Film Festival, where Kitty Winn won a prize for Best Actress. Schatzberg reflects on a conversation he had with Sergio Leone, who was on the jury and ‘fought for the film’ as he admired it very much. - ‘Panic in the Streets of New York’ (25:31). In this interview with Schatzberg from 2011, he discusses his first film, Puzzle of a Downfall Child, which he never expected to lead to more films. He comments on how he came to be involved in the making of The Panic of Needle Park. He reveals that the studio thought Pacino ‘was too old for the part’ and Schatzberg considered some other actors, including Robert De Niro, but felt that Pacino was ideal for the role. Adam Holender, the cinematographer on the film, is also interviewed, and he discusses moving from Poland to New York. He talks about the culture shock he experienced upon arriving in America. Holender reflects on how he came to work with Schatzberg. Both men comment on how they shot the film and the use of very long lenses (of 400mm or 600mm) that required Schatzberg to look at his actors through binoculars. - ‘Writers in Needle Park’ (9:19). In interviews conducted in 2011, the film’s co-writers, Joan Didion, reflects on how she adapted of Mills’ book. She discusses the research involved in writing the script. She reveals that she saw Helen as the lead role in the film, which for her was ‘about a middle-class girl who got mixed up with a junkie’, but Schatzberg saw Pacino as the lead in the film. - The film’s original trailer (2:52).

Overall

For all its graphic qualities and its stark look at the lives of drug addicts, The Panic in Needle Park is to some extent a deeply conservative film, drawing a connection between addiction and crime and suggesting, as Susan Boyd argues, that ‘heroin users are [all] recidivist criminal addicts’. There’s a sense of fatalism and inevitability in the narrative, in Helen’s trajectory from naïve girl from Fort Wayne to drug addict to prostitute and then finally to ‘rat’. The necessity to ‘rat up’ and not ‘rat down’ means that she will forever be caught in a trap, imperiled by both the law and her associates within the world of the addicts on the street. The picture tries to balance its representations of the exuberance of the underground community with the loneliness that comes in the quiet moments: for every scene of Bobby and his friends conversing enthusiastically on the streets, there is a scene showing Helen at home, alone and isolated as her lover, rendered impotent by his addictions, lies passively at her side. For all its graphic qualities and its stark look at the lives of drug addicts, The Panic in Needle Park is to some extent a deeply conservative film, drawing a connection between addiction and crime and suggesting, as Susan Boyd argues, that ‘heroin users are [all] recidivist criminal addicts’. There’s a sense of fatalism and inevitability in the narrative, in Helen’s trajectory from naïve girl from Fort Wayne to drug addict to prostitute and then finally to ‘rat’. The necessity to ‘rat up’ and not ‘rat down’ means that she will forever be caught in a trap, imperiled by both the law and her associates within the world of the addicts on the street. The picture tries to balance its representations of the exuberance of the underground community with the loneliness that comes in the quiet moments: for every scene of Bobby and his friends conversing enthusiastically on the streets, there is a scene showing Helen at home, alone and isolated as her lover, rendered impotent by his addictions, lies passively at her side.

It’s an amazingly constructed film, however, with beautiful photography – and it’s arguably one of the few films in which the employment of the techniques associated with observational documentaries is wholly effective. The impressive acting by the two leads (it’s a shame Kitty Winn didn’t have the career that Pacino did subsequent to this picture, as her performance is equal to his) is carried by some superb performances by recognisable faces in smaller roles: for example, Paul Sorvino appears in a very brief role as a john of Helen’s who accuses her of stealing money from his wallet. Signal One’s Blu-ray release continues their deeply impressive line of releases. The presentation of the main feature is stellar and is accompanied by some excellent extra features. Given the quality of the main feature and the pretty much faultless qualities of this release, Signal One’s Blu-ray release of The Panic in Needle Park comes with the strongest recommendation. References: Boyd, Susan C, 2008: Hooked: Drug War Films in Britain, Canada, and the United States. London: Routledge Mather, Philippe, 2013: Stanley Kubrick at Look Magazine: Authorship and Genre in Photojournalism and Film. Bristol: Intellect Books Over, William, 2004: World Peace, Mass Culture, and National Policies. London: Prager

|

|||||

|