|

The Film

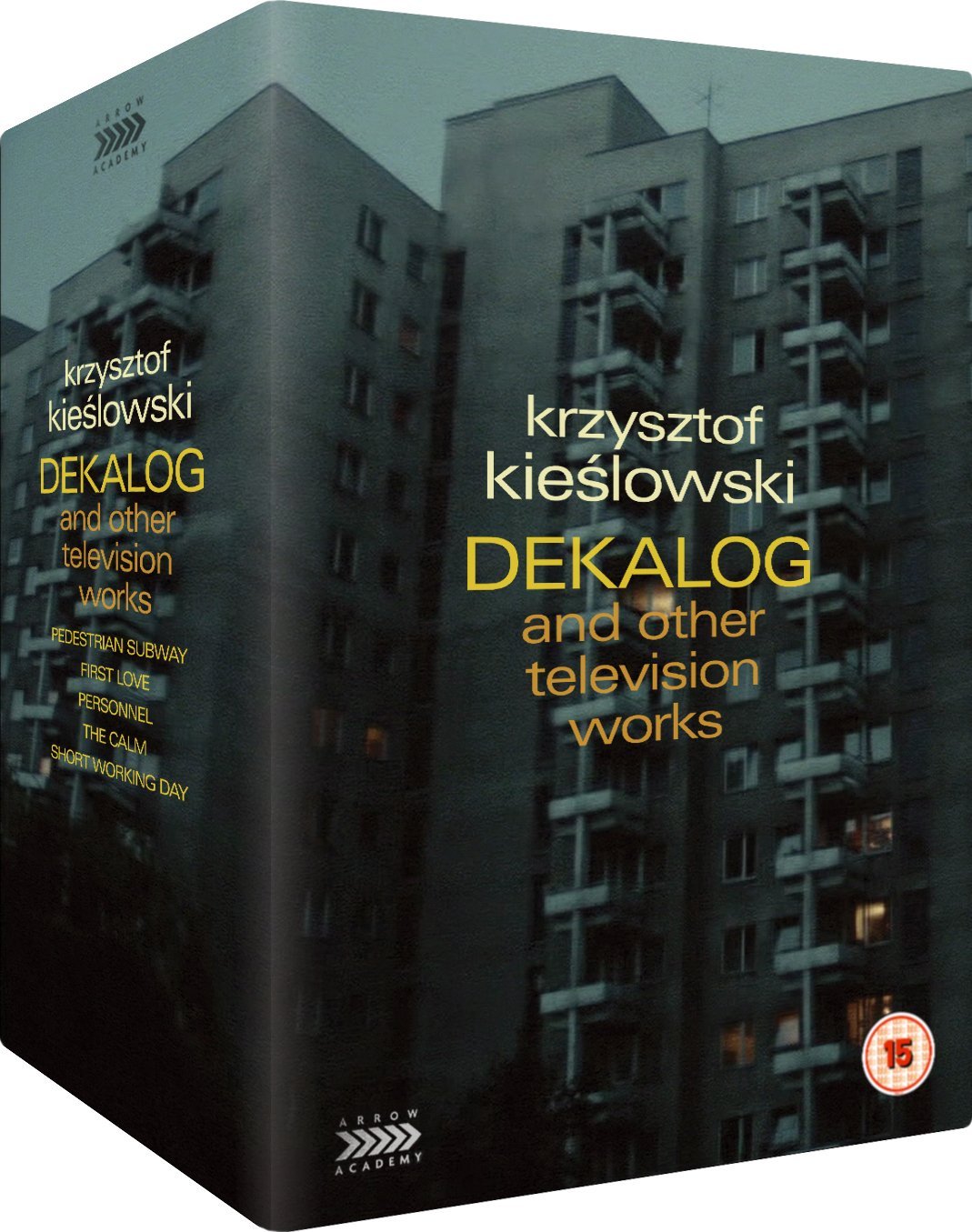

Dekalog (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1988-9)

NB. For the purposes of this review, we were only given access to copies of the DVDs contained within the set, not the Blu-ray discs.

Like many other places in Europe, including the United Kingdom, during the 1960s Poland saw the building of faceless high rises and concrete housing complexes as a solution to urban planning problems. In the 1980s, a song by the Polish singer Martyna Jakubowicz declared ‘There is no free love in a house made of concrete/ Only married relations and naked debauchery/ Casanova is not welcome here’. As if to prove the veracity of Jakubowicz’s assertions that such landscapes were inherently inhuman (shared by many critics of such housing developments across Europe: for example, in J G Ballard’s 1975 novel High Rise), Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Dekalog (1988-9) used one such complex in Warsaw as the setting for Kieslowski’s exploration of the relevance of the Ten Commandments for modern life. Each episode explores one of the commandments through a narrative revolving around one (or sometimes a couple) of inhabitants of the Warsaw housing complex in which Dekalog is set. Though not named in the series, Dekalog takes place in the Ursynów district.

As David Crowley notes, one of the criticisms most commonly ‘levelled against such places’ is that ‘they were anonymous environments’ (Crowley, 2003: 175). Critics often ‘identified not material but moral shortcomings in the neighbourhoods produced in the command economy’ (ibid.: 176). Underscoring this impression of the housing complex as an anonymous place in which people live disconnected lives, Kieslowski shows the inhabitants living insular lives. A failure to ‘only connect’ is at the heart of many of the stories: the father in ‘Dekalog, One’ who is unaware of the death of his son, who has fallen through the ice on the lake, even though a rescue attempt is being made by the fire department and a large crowd has gathered; the doctor in ‘Dekalog, Two’ who initially refuses to help his pregnant neighbour, reminding her that she ran over his dog a few years prior; the young man, Tomek, in ‘Dekalog, Six’ who seems to have no meaningful relationships and becomes obsessed with the older woman in the apartment opposite his, his nighttime use of the telescope to watch her underscoring how isolated each of them is. Kieslowski saw the series as predicated on discontinuity, preferring to refer to Dekalog as ‘a cycle’ owing to the fact that ‘[u]nlike in a regular television series, characters do not regularly appear, and there is no progression of narrative from week to week’ (Badowska & Parmeggiani, 2016: 2). As if to underscore their isolation, Kieslowski allows these narratives to overlap briefly, the inhabitants of the housing complex often meeting each other briefly without recognising one another or alluding to the other stories in the series. Tomek, from ‘Dekalog, Six’, is seen working in the post office in ‘Dekalog, Ten’; in ‘Dekalog, Eight’ during the class in ethics at the university, one of the students posits a question that alludes to the events depicted in ‘Dekalog, Two’, and later the deceased father of the brothers in ‘Dekalog, Ten’ arrives at the lecturer’s apartment to show her his prized stamps (which will become a pivotal part of the plotting of ‘Dekalog, Ten’).

The series originated by chance, following a meeting in Warsaw of Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz, a lawyer and friend of Kieslowski’s who would co-write the ten episodes of Dekalog with the director. Kieslowski originally intended for someone else to direct the series, seeing it as an opportunity to give a young director ‘a great debut project’ (Badowska & Parmeggiani, op cit.: 1).

As David Crowley suggests, in Dekalog ‘petty-minded bureaucrats reign over those they are employed to serve and […] even the most basic things persistently refuse to work’ (Crowley, op cit.: 178). Given the narrative context and the suggestion in public discourse that the high-rise developments were sites of ‘moral shortcomings’, ‘[i]t is not perhaps surprising then that a cluster of high-rise blocks is the main stage for these morality plays’ (ibid.). The films narrativise ‘the upsurge of desperate emotions and chance events that disrupt “normal” relations between family members and friends’ and thereby present the characters in each story with ‘hard choices’ (ibid.). The films thus present the commandments as ‘not dogma but a matter of dilemma’: in effect, like the hypothetical ethical situations with which the protagonist of ‘Dekalog, Eight’, a university lecturer in ethics, presents her students. Crowley observes that the films are as much about ‘spatial relationships’ between people as they are about ‘emotional intimacy’: Crowley notes the recurring use of reflections throughout the series of films, with Kieslowski ‘us[ing] the windows that face each other across bare spaces of the housing estate to create not only a world of vistas and perspectives, but also of limits’ (ibid.). Ultimately, when taken as a whole, the group of films suggest – for Crowley at least – ‘that the damage done to society during the People’s Republic – represented as the housing estate – did not result from the lack of privacy but from an excess of it’ (ibid.: 179).

‘Dekalog, One’

‘Thou shalt have no other gods before me’. ‘Thou shalt have no other gods before me’.

Krzysztof lives with his ten year old son Pawel. An atheist, Krzysztof is contrasted with his sister Irena, who has deeply held Catholic beliefs. Irena is concerned about Pawel’s spiritual development, given Krzysztof’s antipathy towards the faith in which Irena invests. She enrolls Pawel in classes at the local Catholic church. Meanwhile, Krzysztof lectures in computing, and Pawel shows himself to be a wiz at programming the computer which father and son have in the apartment in which they live.

One night, Pawel asks his father if the ice on the lake near to the housing complex is thick enough for Pawel to skate on. Krzysztof runs the query through a computer programme which suggests that yes, the ice is indeed thick enough. Working at home the next day, Krzysztof hears a commotion outside: a fire engine racing along the street and so on. He is told by a neighbour that ‘The ice broke on the pond’. Later, realising that Pawel hasn’t returned from school, Krzysztof goes out looking for his son. He sees a crowd gathered round the frozen lake and witnesses the small body of a child being lifted out of a hole in the ice.

The episode begins enigmatically and bleakly, with shots of the frozen lake near the complex, in which Pawel will die tragically, and shortly afterwards Pawel’s discovery of a dead dog. The latter is the incident which precipitates Pawel’s existential crisis, during which his aunt tries to guide him towards the church. ‘What is death?’, Pawel asks his father, ‘What’s left after [death]?’ ‘What a man has done’, Krzysztof tells his son, ‘The memory of that, of him [….] There’s no soul’. ‘Auntie says there is’, Pawel says. ‘Some people find it easier to live if they think so’, Krzysztof suggests. ‘What’s the point of anything?’, a clearly distressed Pawel then questions. Irena’s faith is juxtaposed with Krzysztof’s materialism: the latter deconstructs the human/inhuman dualism, suggesting in a lecture witnessed by Pawel that computers can be like people – and vice versa (‘I believe that a suitable programmed computer can have its own taste, aesthetic preferences personality’, Krzysztof tells the gathered students). Irena tells the cild that she and Krzysztof were brought up in a Catholic home. He [Krzysztof] noticed much earlier than me that things can be counted and measured. He concluded that everything can be measured [….] His life may seem more rational, but that doesn’t mean there is no God’. Pawel’s death comes as a consequence of the faith that his father places in the computer programme which asserts that the ice on the lake is thick enough for Pawel to skate on. The episode ends ominously with the monitor of the computer, in which Krzysztof invested so much faith, stating ‘I am ready…’ As the bereaved father stares at the screen, we are left with the questions which we presume to be on the mind of Krzysztof regarding the computer’s sentience and its culpability in the death of Krsysztof’s innocent son Pawel.

Offering a heartbreaking opening to the series, ‘Dekalog, One’s portrait of the death of a child owing to the faith his father places in a computer programme is utterly devastating, especially if one is a parent.

‘Dekalog, Two’

‘Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain’. ‘Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain’.

An elderly doctor who lives in the housing complex is approached by a neighbour, Dorota, whose husband Andrzej is critically ill. Reminding Dorota that she ran over his dog with her car two years prior, the doctor is initially reluctant to listen Dorota, but eventually grants her counsel. When he does so, Dorota tells him that though with her husband she found it impossible to become pregnant, she has taken a lover and is now with child. Dorota is concerned that if her husband recovers she cannot have another man’s child, but that if she aborts the baby she may never have another opportunity to be a mother. Dorota makes plans to have the abortion but the doctor advises her not to, telling her that Andrzej’s condition seems to be worsening. Dorota makes an about face, deciding to have the child – but Andrzej makes a miraculous recovery.

The episode focuses on the elderly doctor’s dilemma; the doctor, whose wife and child were apparently killed during the war, lives a lonely life. His isolation is juxtaposed with that of Dorota. Dorota’s problem revolves around her husband and her pregnancy: ‘If my husband recovers, I can’t have this child’, she tells the doctor, but if she aborts the baby she may to have another chance to be a mother. She asks the doctor if it is possible ‘to love two men at the same time’. ‘One of them, my husband, gave me peace; the other gave me… You can’t want everything at once: that’s pride’, Dorota says. The doctor tells Dorota that Andrzej’s chances of pulling through are slim but that he has seen many patients in more dire straits beat the odds. Given the narrative context, Andrzej’s recovery seems inevitable, and this takes place in a marvelous scene which contrasts Andrzej’s recovery with macro shots of a bee drowning in a drink which miraculously manages to climb out of the glass into which it has fallen.

‘Dekalog, Three’

‘Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy’. ‘Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy’.

At Christmas, a taxi driver, Janusz, is approached by his former mistress Ewa. Ewa demands that Janusz help her find her husband Edward. Afraid of the shame Ewa might bring to him, Janusz accepts this quest, which takes him away from his family. Ewa and Janusz search for Edward throughout the city: in the morgue, in the drunk tank, and so on. Ewa blames Janusz for Edward’s disappearance, suggesting that Janusz called Edward anonymously and told him of the affair between Ewa and Janusz. At seven in the morning, after Janusz and Ewa have spent the better part of the night searching for Edward, Ewa reveals that Edward left her not long after her affair with Ewa and that Edward is now married to someone else. Ewa suggests to Janusz that their quest was part of a ‘game’ she had set for herself, to take Janusz away from his family for seven hours: had she not been successful in this endeavour, she would have committed suicide.

In this episode, Janusz’s guilt about his affair with Ewa keeps his quest to find Edward a secret from his family and leads to Janusz being separated from his wife and children: he tells his wife that his taxi has been stolen, this lie giving him the pretext he needs in order to help Ewa find her husband. Meanwhile, Ewa criticises Janusz for his behaviour during the affair and his abandonment of her: ‘You wanted to get rid of me and go back to your wife’, Ewa tells him accusingly, ‘You wanted a trouble-free life [….] You’re just like all the others’. Later she tells him angrily, ‘You worked hard to tidy up your life’. In some ways, the manner in which, given the Christmas setting, Ewa takes Janusz away from his life and forces him to reflect on his past behaviour, suggests the influence of Charles Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol. The Christmas setting is juxtaposed with some of the cruelty Ewa and Janusz see during their sojourn into the underbelly of the city: the corpse of a man whose legs were torn off in an automobile accident who awaits identification in the hospital morgue; the drunk tank, in which the attendant cruelly hoses down the drunks with cold water, all the while displaying a gleeful sense of sadism.

‘Dekalog, Four’

‘Honour thy father and thy mother’. ‘Honour thy father and thy mother’.

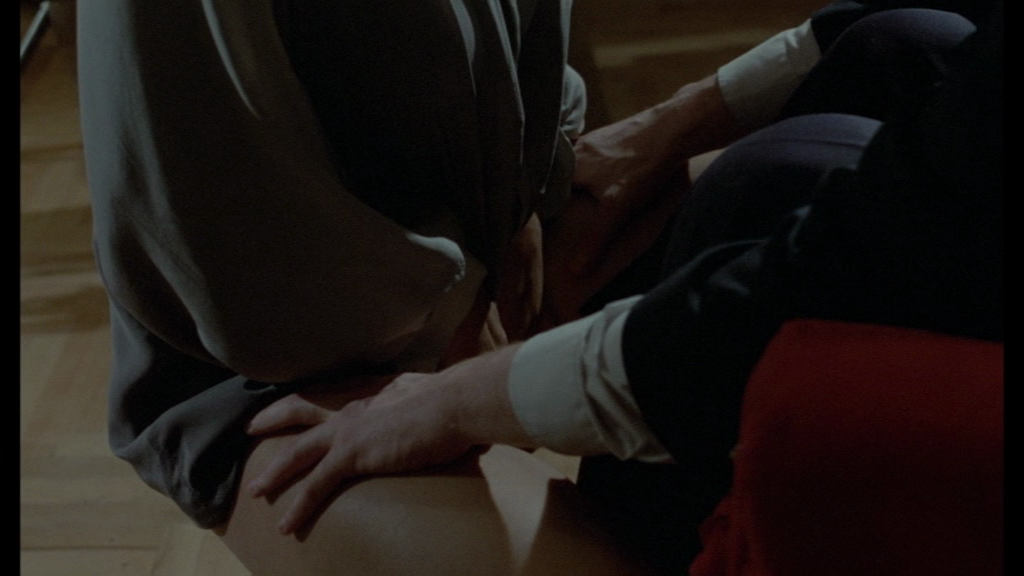

Michal lives with his twenty year old daughter Anka. Anka and Michal behave more like friends than father and daughter. One day, whilst Michal is on a business trip, Anka discovers amongst his things an envelope reading ‘Open after my death’. Inside this envelope is another, in different handwriting: ‘For my daugher Anka’. When Michal returns home, Anka reads the contents of the letter, from Anka’s deceased mother, to him: ‘Michal is not your father’, it says, ‘It is not important who is […] I know that Michal will love you just like his own daughter’. Anka and Michal argue. They eventually reconcile, Michal telling Anka that he had planned to give Anka the sealed envelope, whose contents he seems to have been uncertain of, a number of times in the past but always stopped himself before doing so. Anka tells Michal that with her lovers she has always felt she was betraying someone: ‘I’ve always felt guilty in bed. Now I know why: I was betraying you’. Alone with Michal at night, Anka suggests that she desires Michal in a sexual way: Michal seems tempted to reciprocate but withdraws. When, the next morning, Anka awakens to find Michal has left the apartment, apparently for good, she manages to catch up to him and tells him that she never opened the envelope. The pair seem to come to a complicit agreement that they will go back to the way things were before Anka’s revelation, and together they burn the unopened envelope.

From the outset, the audience is given a hint of something unresolved within Anka and Michal’s relationship which manifests itself as sexual tension. There’s a subtle hint of incestuous longing when Anka and Michal, playing in the apartment in which they live, are shown in the bathroom – where Michal sprays Anka with water, the liquid causing her white nightgown to appear almost transparent. Michal pauses, looking his daughter up and down before excusing himself. The revelation that Michal is not Anka’s father changes their relationship, Anka initially telling her boyfriend that they do not need to seek Michal’s permission to marry: ‘It doesn’t matter’, Anka asserts, ‘He’s not my father’. Later, after she and Michal have reconciled, Anka tells Michal that with her lovers ‘I felt that I betrayed someone, even with my first boyfriend. It was you [….] What shall I call you now?’ She asks Michal, ‘Who are you afraid of? Me or yourself?’ She undresses in front of Michal: ‘I’m not your daughter. I’m a grown up. Do you want to touch me?’ However, Michal simply covers her up with a blanket. Most significantly, the final moments of the installment render ambiguous Anka’s suggestion that she is not Michal’s daughter: it seems that Anka did not open the letter after all, and she and Michal burn the envelope whilst seeming to agree that they will return to the parent-child relationship they shared before. The episode hints at the notion of the performativity of identity, a theme which links a number of episodes in the series: Anka’s declaration that Michal is not her father, brough about by her ‘faked’ reading of the letter from her dead mother, changes their relationship; but at the end of the episode, they choose to return to how things were before. This theme of identity-as-performance is anchored by scenes showing Anka in her drama classes at the university, learning how to act.

‘Dekalog, Five’

‘Thou shalt not kill’. ‘Thou shalt not kill’.

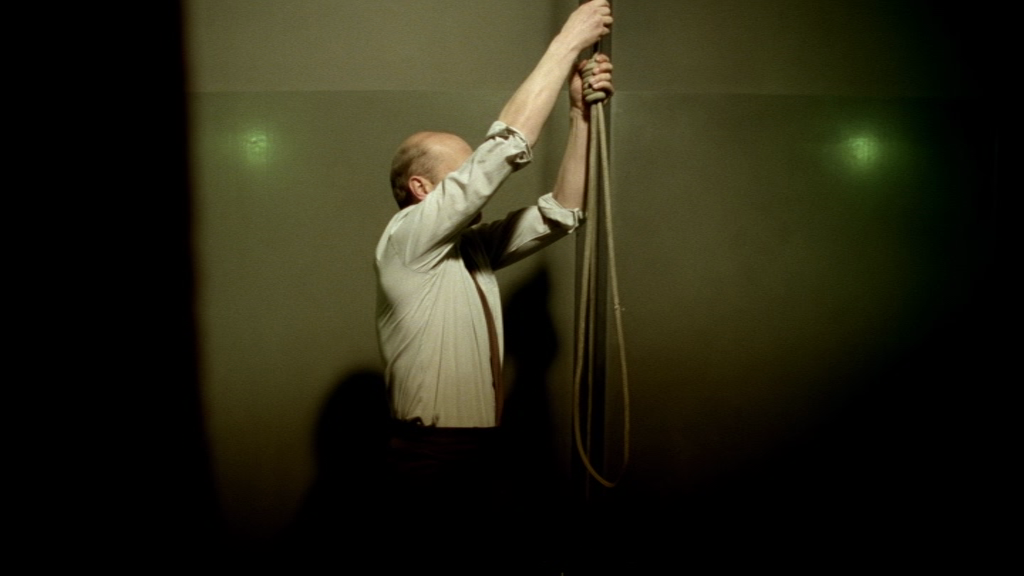

Twenty year old Jacek wanders the streets of Warsaw, committing escalating acts of destruction: pushing a man into a urinal trough, flicking coffee at the window of a café. Jacek’s behaviour, the film suggests, is linked somehow to a creased photograph of a young girl that he takes into a photographic studio and asks for it to be enlarged. His actions are intercut with an interview with a young and idealistic lawyer, Piotr, and a middle-aged taxi driver, Waldemar. In his interview, Piotr argues vehemently against the death penalty. Meanwhile, Jacek enters Waldemar’s taxi and asks the driver to take him to a deserted location. There, Jacek attempts to strangle Waldemar with a length of rope Jacek has carried with him. Waldemar passes out and Jacek drags the large man from the taxi to the riverbank. Waldemar regains consciousness and begs for his life but Jacek stoves the taxi driver’s head in with a rock before experiencing a moment of regret and grief.

The episode cuts to a period after the arrest and trial of Jacek for the murder of Waldemar. Piotr, it seems, has attempted to prevent the state from issuing the death penalty – but to no avail. Jacek is to be hanged. Prior to Jacek’s execution, Piotr meets with the condemned man. Jacek reveals that the photograph is of his sister Marysia, who died after being run over by the driver of a tractor; the tractor driver had previously been drinking with Jacek, and thus Jacek blames himself for the death of Marysia. Piotr attempts to forestall Jacek’s execution, but Piotr’s actions have no effect. Jacek is hanged, his death at the rope echoing Jacek’s own attempt to strangle Waldemar – the futility of the two ‘murders’ clashing and echoing in the viewer’s mind.

The structure of this episode is arguably very didactic: from the outset, the episode cross-cuts between the young lawyer who defends Jacek being interviewed about his feelings regarding the right of the law to punish offenders, and Jacek himself as he wanders the streets of Warsaw in the build-up to his murder of the taxi driver, the cross-cutting working almost like the thesis/anti-thesis structure of an essay. From the outset, Piotr demonstrates strong concerns about the legal system, suggesting that his ‘profession allows one to repair mistakes made by that juggernaut we call the machinery of justice’. Jacek, meanwhile, is shown enacting various seemingly motiveless acts of vandalism and aggression; his lashing out at the world seems to evidence a sense of despair, frustration and envy.

The photograph Jacek carries, and which he takes into a photographic studio asking for it to be enlarged, takes on a pivotal importance as the narrative progresses. Handing the photograph to the woman in the studio, Jacek asks if one can tell from a photograph of a person whether that person is dead or alive. Later, it is revealed that the photograph is of Jacek’s sister, whose death Jacek blames himself for, and the image is used to humanise Jacek in the eyes of Piotr. Interestingly, during Jacek’s murder of Waldemar the taxi driver attempts to humanise himself to his killer via similar appeals: Waldemar first attempts to bribe Jacek, telling the young man that he has money, and when this fails Waldemar attempts to humanise himself by referring to his wife. ‘The safe… money… my wife’, Waldemar gasps, this series of non-sequiturs suggesting Waldemar is trying to bargain with Jacek before humanising himself and therefore attempting to appeal to the killer’s sense of humanity – in a similar manner to which Jacek’s memories of his sister appeal to Piotr’s sense of humanity. The revelation towards the end of the episode that Jacek blames himself for the death of his twelve year old sister Marysia explains but doesn’t mitigate his murder of Waldemar. When Jacek is hanged, it is as cruel and unpleasant as Jacek’s murder of the taxi driver, the closed room in which the execution happens signifying a sense of concealed shame about what is taking place. Ultimately, given the seeming futility of Piotr’s attempts to act against the death penalty, the viewer is left with the counsel given to Piotr by one of his colleagues: ‘You are too sensitive for this profession [….] Today you have become a little older’.

‘Dekalog, Six’

‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife’. ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife’.

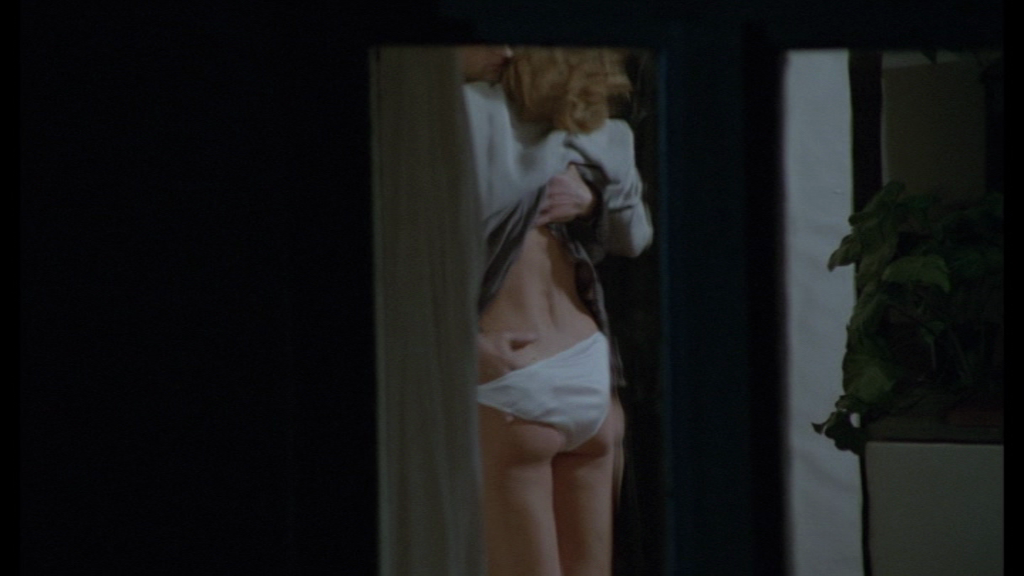

Orphan Tomek, nineteen years old, lodges with his friend’s mother. Working at the post office, Tomek becomes obsessed with one of his customers, Magda. In her thirties, Magda lives in one of the apartments opposite Tomek’s. At night, Tomek uses a telescope to spy on Magda and her lovers. In order to become closer to Magda, Tomek takes a job delivering milk to the apartments. When, one day, Tomek decides to tell Magda he watches her, she reacts angrily. However, that night, aware that Tomek is watching her through his telescope Magda ‘entertains’ one of her lovers, putting on a show for the young man; she interrupts their love making to tell her lover that Tomek is watching them. The man storms out of the building and shouts for Tomek to come down. Tomek does as he is told and is hit by the man.

Magda meets with Tomek and agrees to go to dinner with him. Tomek tells her that he has been watching her for a year. Magda takes Tomek home. Unbeknownst to Tomek, his landlady has found the telescope and watches what ensues with disapproval. Magda seduces Tomek, placing his hands on her bare knees and moving them up to her groin. Tomek ejaculates in his trousers and is humiliated. Tomek returns home and attempts suicide by slitting his wrists. He is saved, but his outlook on love and sex will forever be shaped by his encounter with Magda.

The pivot of the film is Tomek’s erotic fascination with Magda. The scenes of Tomek watching Magda through his telescope, the window frames through which he spies acting as a metonym for the limits of the cinema/television screen, instantly recall Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) in their foregrounding of the theme of voyeurism and, through the representation of this, the connections they draw between Tomek’s acts of voyeurism and the experience of viewing a film (whether made for television or not). Tomek ensures that Magda’s experiences with her lovers are interrupted by, for example, telephoning the fire brigade and reporting a gas leak at her apartment.

Living an isolated life, Tomek is naïve in his understanding of love. His friend’s mother, with whom he lodges, tries to guide him, telling him ‘Girls only pretend to be free and easy, but the truth is they like gentle guys’. For Tomek, the gaze is connected to love but not necessarily to sex. ‘Why do you spy on me?’, Magda asks him. ‘Because I love you’, he says. ‘Do you want to make love to me?’, she asks. ‘No’, Tomek replies. On the other hand, Magda devalues love and separates it from sexuality. She takes Tomek out to dinner, then returns with him to her apartment. She asks Tomek what he sees when she brings men back to her apartment with her. ‘You make love’, Tomek says. ‘It has nothing to do with love’, Magda tells him, ‘Tell me what you see’. ‘You take off your clothes… and you… You undress them too’, Tomek says. Magda asks Tomek ‘do you do it to yourself’ when he watches her, reminding him that ‘it’s [masturbation is] a sin’. When Magda seduces Tomek, moving his hands to her crotch, he ejaculates in his trousers and is ridden with shame. ‘That’s all there is to love’, Magda tells him coldly.

‘Dekalog, Seven’

‘Thou shalt not steal’. ‘Thou shalt not steal’.

Young Ania has been raised by her grandparents, believing them to be her real parents, owing to the shame brought on the family by the youth of Ania’s mother, Majka. Majka conceived Ania after a fling with Wojtek, one of the teachers at her school, at a time when Majka’s mother Ewa was the headmistress. During a concert at Ania’s school, Majka abducts the child, planning to flee with her to Canada. However, Majka first takes Ania to visit Wojtek, who now lives in the woods making teddy bears. She calls Ewa, telling her ‘You stole my child’. Threatening to take Ania out of the country to Canada, Majka antagonises Ewa. However, Ewa catches up with Ania and Majka. As Ewa and Ania are reunited, Majka addressing Ewa as ‘Mum’ (the title she would never use to address Majka, much to the latter’s discontent), Ania leaves on the train – alone.

The fallout from Majka’s pregnancy is shown to touch everyone: Ania’s biological father, Majka’s former teacher, has been forced to give up his teaching post and now lives in the woods, like a creature from a folk tale, making teddy bears to order. ‘What about your studies, your plans, you writing?’, Majka asks when she sees Wojtek for the first time since she became pregnant with Ania. ‘I gave them up’, he replies matter-of-factly. She attempts to represent herself in a different light to him: ‘I’m no longer the nice girl in a navy blue skirt who fell in love with her Polish teacher because his classes were different’. Majka desires to be recognised as Ania’s mother but seems not to have the skillset required in order to become a ‘good’ parent. The episode begins with Majka being expelled from school and buying tickets to Canada, planning to abduct Ania. This is intercut with Ania screaming whilst in her cot at Majka’s parents’ apartment. Majka returns home and is distraught that Ania has been left to shout, until Ewa enters and calms the child down. Later, at Wojtek’s place Ania wakes from a nightmare screaming in a similar manner. Frustrated when the child won’t calm down, Majka begins to shake Ania; Wojtek tells Majka that she is too rough with the child. Some of Majka’s behaviour seems to be motivated by simple jealousy. Ewa treats Ania kindly; Majka is frustrated by this, considering Ewa to treat Majka with coldness. However, despite Majka’s protestations to Ania that ‘Mum is not your real mum [….] I’m your real mum’, Ania refuses to address Majka anything other than by her first name. When Ewa arrives at the end of the episode, the separation between Majka and Ania is signaled in Ania’s instinctive use of the name ‘Mum’ to address Ewa: regardless of which woman is her biological mother, for Ania Ewa will always be ‘Mum’. Ania leaves, alone, on the train – presumably destined for a new life in Canada.

‘Dekalog, Eight’

‘Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour’. ‘Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour’.

American academic Elzbieta returns to Warsaw to meet with a lecturer in ethics at the University of Warsaw, Zofia. Elzbieta has translated a number of Zofia’s books into English for publication in America. Whilst sitting in on one of Zofia’s lectures, Elzbieta posits an ethical dilemma: she reflects on the Holocaust and a Catholic woman who refused to provide a six year old Jewish girl with shelter but, owing to the guilt she felt afterwards, offered shelter to many other Jews. The woman was, of course, Zofia, and the child was Elzbieta. Zofia suddenly recognises Elzbieta as the girl she refused shelter to over forty years earlier; Elzbieta questions the explanation Zofia gives in the lecture, that the Catholic family couldn’t lie about the fake baptism offered the child. Elzbieta and Zofia spend some time together afterwards, and Elzbieta tells Zofia the real reason why she (Zofia) didn’t offer Elzbieta shelter: Zofia’s husband was a high ranking member of the Polish Resistance, and they believed Zofia’s guardian to be collaborating with the occupying Nazi forces. Fearing that Zofia’s guardian would lead the SS to the doorstep of Zofia and her husband, and therefore would lead to the SS gaining a stranglehold over the Resistance, Zofia decided not to offer shelter to Elzbieta.

Based on a true story recounted to Kieslowski by an acquaintance, ‘Dekalog, Eight’ contrasts Zofia and Elzbieta, and through them America and Poland. In Zofia’s lectures, students are invited to pose ethical problems. One student recounts the dilemma of the doctor as presented in ‘Dekalog, Two’; Elzbieta, sitting in on Zofia’s lecture, offers the tale of the two women’s own experiences during the Nazi occupation. To this point, Zofia has been unaware of Elzbieta’s identity as the six year old girl to whom Zofia and her husband refused shelter. When Elzbieta has recounted the central situation, she suggests a motive for Zofia’s refusal: ‘On reflection they’ve [Zofia and her husband have] found that it is not in them to lie before the God in whom they believe [about the Jewish Elzbieta being Catholic] – who, it is true, enjoins mercy but forbids the bearing of false witness’. However, Elzbieta doesn’t criticise Zofia for the decision she made: ‘It is well known how you behaved after that business with me’, she tells the lecturer – Zofia subsequently offered a number of other people shelter from the Nazis.

‘Dekalog, Nine’

‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’. ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’.

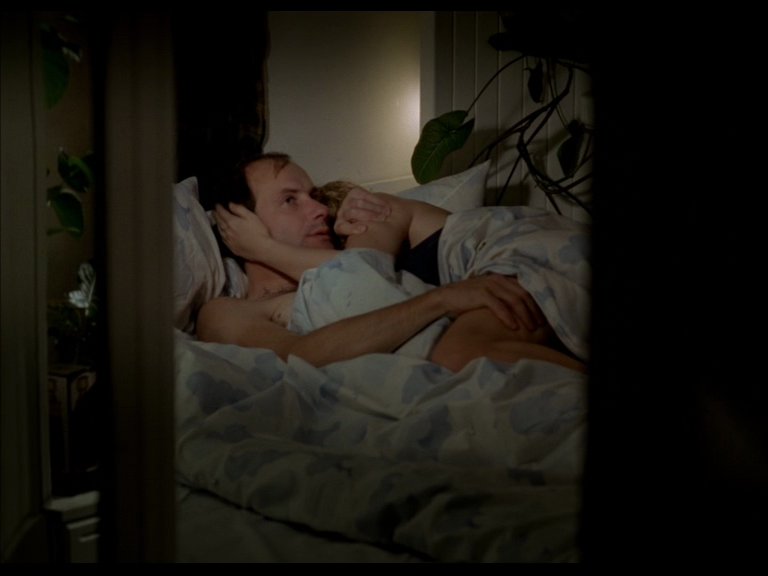

Dr Romek Nycz visits a doctor friend who informs Romek that he (Romek) is innocent. Romek struggles with this news, hesitating to inform his wife Hanka. He insists that Hanka will ‘have to find somebody [to satisfy her sexual needs], if you haven’t already’. Meanwhile, Romek becomes fascinated by one of his patients at the hospital, a young woman whose illness has prevented her from fulfilling her potential as a singer. He discovers that Hanka has taken a lover, a physicist named Mariusz. Romek becomes jealous. Hanka attempts to break off her affair with Mariusz, but Mariusz is persistent. One day, Romek hides in a wardrobe and watches Hanka with Mariusz. He expects to see them have sex, but instead Hanka tells Mariusz that she does not want to see him anymore. As Mariusz leaves, Hanka becomes aware of Romek’s presence; at first, she believes that he is simply after a voyeuristic thrill, but she soon realises that Romek was spying on her out of jealousy and insecurity.

Romek and Hanka reconcile, and Romek suggests to Hanka that she should take a holiday. Hanka agrees, somewhat reluctantly, and visits a skiing resort. However, Mariusz has discovered where Hanka is going and follows her there. Hanka becomes aware of Mariusz’s presence at the ski resort and panics, believing that Romek will also be aware that Mariusz has followed her. She is correct: Romek sees Mariusz carrying skis and deduces that he is following Hanka. In response, Romek decides to commit suicide.

In some ways, this episode offers a counterpoint to the representation of love and sexuality in ‘Dekalog, Six’. From the outset, marriage is equated in the eyes of Romek with sexual potency. ‘Got a nice wife?’, the doctor who Romek consults in the opening sequence asks him before asserting, ‘Get divorced’. When Romek tells Hanka that his impotence has been confirmed, he says ‘There’s no hope. Either now or ever. Never’. ‘Love isn’t about gymnastics in bed’, Hanka says, offering an alternate point of view: ‘Love’s located in the heart, not between the words’. (Her words about love contrast with those of Magda to Tomek.) Hanka reluctantly takes a lover, Mariusz; she does this seemingly only to satisfy Romek. When Hanka and Mariusz are shown in bed together, Mariusz on top of Hanka, Hanka’s face is turned away from him towards the camera and tears are shown streaming down her cheeks. As Romek becomes aware of Hanka’s affair with Mariusz, he reacts with jealousy. He drops subtle hints to Hanka that he is aware of her relationship with Mariusz, which is entirely sexual: he reflects on Hanka’s fascination with Archimedes principle, that ‘The weight of the water displaced by a body entering it equals the weight of the body’. It’s clear that Romek feels ‘displaced’ in Hanka’s life by Mariusz. ‘I’ve no right to be jealous’, Romek says after Hanka has found him spying on her from the wardrobe following her conversation with Mariusz. ‘Nothing should be unsaid’, Hanka tells him in response, ‘From now on, I will always tell you the truth’.

‘Dekalog, Ten’

‘Thou shalt not covet they neighbour’s ox’. ‘Thou shalt not covet they neighbour’s ox’.

Jerzy approaches his brother Artur – the latter being a singer in a punk band named ‘City Death’ – and informs him that their father has died. Following the funeral, the brothers gather at their father’s apartment and go through his things. They are interrupted by a man to whom their father owed a considerable sum of money. Returning to their father’s things, they find his stamp collection. With Artur’s agreement, Jerzy takes from this collection three stamps from 1931 and gives them to his son.

The following day, Artur visits a fair of stamp collectors and discovers that his and Jerzy’s father’s collection was worth a fortune – especially the three 1931 stamps Jerzy gave to his son. When Jerzy asks his son for these stamps, he is told that his son sold them to a youth on the street; Jerzy investigates this lead and discovers that the stamps have fallen into the hands of an unscrupulous dealer. Artur comes up with a plan to entrap the dealer into asserting his willingness to buy stolen goods, using a recording of this conversation to blackmail the dealer into returning the stamps.

Jerzy becomes aware of another stamp missing from his father’s collection; this stamp was apparently stolen a number of years before. The dealer offers to lead the brothers to this missing stampon one condition: Jerzy must donate a kidney that, the dealer says, will save the life of the dealer’s young granddaughter. Jerzy books in to the hospital, and Artur visits him; but whilst the brothers are away, someone breaks into the apartment and steals the whole stamp collection.

A black comedy, ‘Dekalog, Ten’ stands apart from the other episodes through its focus on humour and its generally light tone. This tone is established in the episode’s opening sequence, in which Jerzy approaches Artur at a performance by Artur’s band ‘City Death’; Artur is singing a song about the commandments. ‘Kill! Kill! Kill! Covet and steal!’, the lyrics of this song assert.

Artur and Jerzy reflect on their father’s valuable stamp collection, gathered whilst the brothers grew up in what they suggest was poverty. ‘How is it that some people are so avid for possessions?’, Artur asks his brother. ‘I like to be comfortable’, Jerzy responds. When Artur makes contact with the chairman of the club that has organised the stamp collectors’ fair, he is told ‘Your father sacrificed his whole life for this collection. It would be shameful to throw away thirty years of someone’s life, even if that someone was a father you hardly knew’.

Video

NB. For the purposes of this review, we were only given access to copies of the DVDs contained within the set, not the Blu-ray discs. NB. For the purposes of this review, we were only given access to copies of the DVDs contained within the set, not the Blu-ray discs.

For the purposes of shooting Dekalog, Kieslowski worked with nine different cinematographers: only one cinematographer, Piotr Sobocinski, lensed more than one episode: Sobocinski lensed ‘Dekalog, Three’ and ‘Dekalog, Nine’.

Aside from ‘Dekalog, Five’ and ‘Dekalog, Six’, all of the episodes are presented in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio. ‘Dekalog, Five’ and ‘Dekalog, Six’ are presented in a different aspect ratio, 1.70:1 – presented on the DVDs included in this set with anamorphic enhancement. ‘Dekalog, Five’ and ‘Dekalog, Six’ were the two installments that were expanded and released as feature films (A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love, respectively). These feature film edits are not included in this release, for reasons relating to rights.

Most of the installments have a fairly naturalistic aesthetic, albeit one which often emphasises cold tones. ‘Dekalog, Five’ stands apart from the others, inasmuch as this particular episode has an interesting, unusual visual style. The image has a bold green/amber tint, achieved via the use of filters on the lenses; further to this, the use throughout the episode of shots of glass, reflection and silhouettes is combined with application of extremely bold vignetting in the photography to create a very oppressive visual design and a theme of ‘tunnel vision’.

The presentations of all episodes are based on new 4k restorations. These look absolutely superb throughout, even on the DVDs provided for this review. A strong level of detail is present throughout, and contrast levels are impressive too: defined midtones are balanced by strong blacks, carrying the many low-light scenes within the series very well.

Audio

For all episodes, audio is presented in Polish with optional English subtitles. Audio is clean and clear throughout, and the subtitles are easy to read and free from distracting errors.

Extras

The disc contents of the DVDs provided for review are as follows:

DISC ONE:

‘Dekalog, One’ (53:31)

‘Dekalog, Two’ (56:53)

‘Pedestrian Subway’ (28:38). This short film by Kieslowski was made in 1973 and focuses on a school teacher who encounters a window-dresser after stealing away from the school in which he works. Shot in monochrome film, this is presented here in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1. Dialogue is in Polish with optional English subtitles.

‘Still Alive’ (81:34). This 2006 documentary focuses on Kieslowski and was made by one of his former students. The documentary features much input from those who knew and worked with Kieslowski. Shot on digital video, the documentary is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.33:1, in Polish and with optional English subtitles.

DISC TWO:

‘Dekalog, Three’ (55:45)

‘Dekalog, Four’ (55:29)

First Love (51:29). A docudrama, this film examines the consequences of an unplanned pregnancy for a pair of young lovers. I rewatched Ken Loach’s Poor Cow (1967) fairly recently, and this short film’s approach to its material, its aesthetic and its examination of love and relationships is remarkably similar to that of the Loach film. Shot on 16mm, First Love is here presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Light but noticeable damage is present throughout. Dialogue is, naturally, in Polish, with optional English subtitles.

‘KKTV’ (75:11). In this new piece, Michael Brooke reflects on Kieslowski’s career, providing a strong context for Dekalog within Kieslowski’s work as a whole. This is a breathless and thorough examination of the director’s oeuvre.

DISC THREE:

‘Dekalog, Five’ (57:32)

‘Dekalog Six’ (58:41)

Personnel (66:35). Made in 1975, this was Kieslowski’s first fictional piece. A television film, Personnel focuses on a theatre company and the internal politics within it. The image is in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio; seemingly shot on 16mm, the presentation has some noticeable print damage but is organic and film-like. Audio is in Polish, with optional English subtitles.

‘Tony Rayns on Dekalog’ (77:58). In this thorough new interview, Tony Rayns reflects on Dekalog and talks about his encounters with Kieslowski. This is an insightful piece, a superb companion to the series.

DISC FOUR:

‘Dekalog, Seven’ (55:10)

‘Dekalog, Eight’ (54:23)

The Calm (81:58). Made in 1976, this television film focuses on Antek, a man who is released from prison and attempts to create a new life for himself. However, he finds himself drawn into an incident at work, when materials begin to go missing. Shot on 16mm, this is presented in the intended aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The Polish dialogue is accompanied by optional English subtitles.

NFT Interview with Kieslowski (92:22). This interview with Kieslowski, recorded at the NFT in 1990 and conducted by Derek Malcolm, was staged for the British premiere of Dekalog. The interview is presented via an audio recording that is accompanied by images from the various films in the series.

DISC FIVE:

‘Dekalog, Nine’ (58:09)

‘Dekalog, Ten’ (57:23)

Short Working Day (77:28). Shot in 1981 and originally banned in its country of production, this television film revolves around a Communist official who is forced to deal with striking workers. This is another 16mm production that is presented in its original broadcast ratio of 1.33:1, with Polish dialogue and optional English subtitles.

Dekalog re-release trailer (1:22).

Overall

The success of Dekalog outside Poland saw Kieslowski hailed as one of modern cinema’s great auteurs. (Anecdotally, I vividly remember watching the series when the BBC showed it in 1990 or thereabouts and being haunted by it, before watching the feature film versions of A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love at my local BFI-funded cinema.) When asked by a journalist if Dekalog was about ‘a moral code’, Kieslowski famously replied that ‘These films are simply about life’ (Kieslowski, quoted in Badowska & Parmeggiani, op cit.: 2). The series’ hermetic, thoughtful examination of moral quandaries in the lives of people within the Warsaw housing complex that forms the locus of the episodes has echoes in Jimmy McGovern’s more recent anthology series The Street (BBC, 2006-9), focusing on the intersecting lives of the inhabitants of the titular street. Nearly thirty years after its first broadcast, Dekalog still feels as relevant and powerful as ever, the moral quandaries having resonance for modern audiences. Some of the episodes are more impactful than others: for example, episode two feels comparatively unfocused when watched immediately after the extremely haunting first episode. However, the whole series is profoundly watchable. The success of Dekalog outside Poland saw Kieslowski hailed as one of modern cinema’s great auteurs. (Anecdotally, I vividly remember watching the series when the BBC showed it in 1990 or thereabouts and being haunted by it, before watching the feature film versions of A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love at my local BFI-funded cinema.) When asked by a journalist if Dekalog was about ‘a moral code’, Kieslowski famously replied that ‘These films are simply about life’ (Kieslowski, quoted in Badowska & Parmeggiani, op cit.: 2). The series’ hermetic, thoughtful examination of moral quandaries in the lives of people within the Warsaw housing complex that forms the locus of the episodes has echoes in Jimmy McGovern’s more recent anthology series The Street (BBC, 2006-9), focusing on the intersecting lives of the inhabitants of the titular street. Nearly thirty years after its first broadcast, Dekalog still feels as relevant and powerful as ever, the moral quandaries having resonance for modern audiences. Some of the episodes are more impactful than others: for example, episode two feels comparatively unfocused when watched immediately after the extremely haunting first episode. However, the whole series is profoundly watchable.

The word ‘exhaustive’ barely scratches the surface of Arrow’s release of Dekalog. The episodes themselves are given very satisfying presentations, and the main feature is supported with some superb contextual material – including some of Kieslowski’s other television work, and the two new, extremely pleasing interviews with Michael Brooke and Tony Rayns. This is without doubt one of the most important home video releases of the year and comes with the strongest recommendation.

References:

Badowska, Eva & Parmeggiani, Francesca, 2016: ‘Introduction: “Within unrest, there is always a question”’. In: Badowska, Eva & Parmeggiani, Francesca (eds), 2016: Of Elephants and Toothaches: Ethics, Politics, and Religion in Krzyzstof Kieslowski’s “Decalogue”. New York: Fordham University Press: 1-14

Crowley, David, 2003: Warsaw. London: Reaktion Books, Ltd

|