|

|

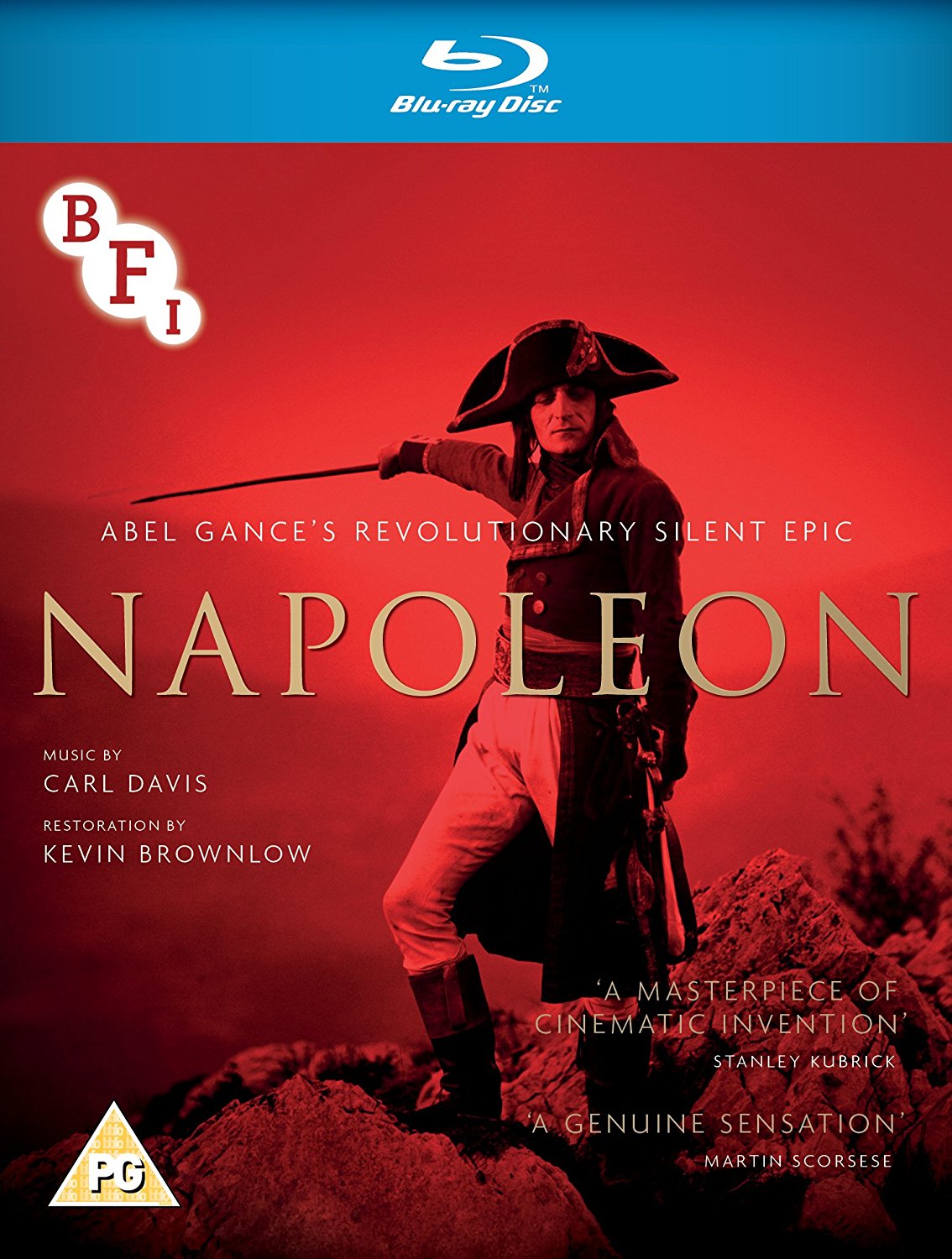

Napoleon AKA Napoléon vu par Abel Gance

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - British Film Institute Review written by and copyright: James-Masaki Ryan (20th November 2016). |

|

The Film

“Napoleon” (1927) The 1927 silent film “Napoleon” is one of the most widely known silent epics ever made, mentioned alongside “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), “Metropolis” (1927) and “Greed” (1924). The biggest problem with fully evaluating these lengthy silent films is that they exist in multiple versions, or don’t exist in a complete version. They exist with previously missing footage being rediscovered over the years, alternate export versions with different edits and cuts, differing music scores, and tinkered reworking by the directors themselves or by the foreign distributors making it extremely difficult to say what version of the film is considered “true”. Director Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” is one of those films to have a convoluted history that is as fascinating as the film itself. And because of that the film has been widely discussed but rarely seen. Gance previously directed “J’accuse” (1919) and “La roue” (1923) - both very lengthy epic tragedy films - the first dealing with WWI and the latter being a relationship between a foster father and adopted daughter. Both were critical successes both in France and abroad, and in 1924 Gance embarked on a quest to try to make his biggest film yet - a film about the life of Napoleon Bonaparte. While immersing himself in historical documents on the man and his life, he envisioned a 6-part film series depicting everything from his birth in 1769 all the way to his exile and death in 1821. Chronicling how a boy from Corsica became one of the most powerful men in human history is a dazzling, incredible, controversial, and nearly mythical story, one that Gance felt could not be told simply in a single film. Unfortunately the 6 part series seemed too big to be done. It was reluctantly cut down to a single film in 4 acts to chronicle his childhood until the first Italian campaign in 1979. The film had to be big - and bigger than his previous films. “J’accuse” had incredible war footage shot on the front lines and with Gance having military experience, he was able to show the shocking effects of war with firsthand knowledge. “La roue” had the large train crash scene, but “Napoleon” was going to not only feel big, but technically innovative. Most silent films were shot with static camera positions as the heavy cameras were not mobile and the only times there was true movement was when it was an outdoor scene where cameras could be mounted to cars with generators required. What is surprising in “Napoleon” is that there are a multitude of scenes with the cameras moving. Not only by being mounted on cars or dollies, but ones that are clearly handheld - which seems nearly impossible at the time. Cameras were specially invented with mounted harnesses attached to the camera operator with lengthy cords for power and assistants helping with operation - very much like a modern production. Motorized cameras were used for motorized pans and film cranking - at a time when most films were manually hand cranked. The visuals are a marvel in the film as there is frequent movement throughout, making it stand apart from the rest of the silent produced at the time. Visual techniques were not only with the camera, but also with the processing technique. The black and white film was tinted and toned in differing scenes - night scenes as blue and war scenes in red - which were a common practice at the time. Superimposed images during war montages - marching soldiers with Napoleon’s face overlayed, the recurring image of the mighty eagle with Napoleon, and much more are used. Double exposure, split screen processing were also used to great capacity creating striking visuals. But the most talked about and most widely known is the “Tryptich” ending of the film. For the finale at the battlefront in Italy, Gance devised a multi-screen process in which the final 15 minute sequence was projected on three standard size movie screens side by side. This meant three screens, three projectors, and three operators completely in sync. Before the advent of Cinemascope or the 3-panel Cinerama widescreen processes, Gance was far ahead by nearly 30 years. This sequence was a huge spectacle that had never been seen or tried before. The 1.33:1 image was suddenly tripled to a 4.00:1 ratio. With three cameras positioned side by side and a cast of 3000 people in the frame, there were technical limitations to get the frames to match up exactly, and with depth of field issues the background mountains look to be lined up, but any person right in front of camera would seemingly disappear due to perspective issues of three lenses. Regardless, it is a grand visual spectacle surpassing anything coming at the time of its making and release. From here, sometimes the three screens would show three different images - sometimes the center would be one image while the left and right would be another. Montages would be intercut with tinting and the epic finale would have the frames tinted from left to right blue / white / red - trois couleur of the French flag. A spectacular finale to a spectacle for the eyes. It took three years from pre-production to finish with extensive location shooting, technical innovations, a large cast, and instances of the film having production issues with money and Gance injuring his hand, it was finally screened in 1927. The film premiered in Paris in April of 1927 and ran a total length of 4 hours at the Paris Opera with a score by Arthur Honegger to accompany the picture. A month later at the Apollo Theater in Paris, a reworked lengthier version of the film played - at a mammoth runtime of 9 hours but without the 3 panel Tryptich finale. There were other versions issued - shorter versions without the Triptych ending for theaters outside Paris, international versions with different shots and takes altogether, and minor tinkering here and there. While a 7 hour version was screened in the UK in 1928, a heavily shortened 2 hour version was released by MGM in America. With so many versions being released around the world it was hard to keep track and to position what the definitive cut of the film was. The 9 hour version appears to be completely lost. As are the original orchestral music score and notes. When film historian Kevin Brownlow was 15 he first encountered “Napoleon” through a 9.5mm home version which was heavily truncated but for the young boy it was awe inspiring to see the fragments of the silent masterpiece. As a n adult he was able to meet Gance in 1965 which led to his quest to restore the film in its full glory. Finding footage was a long and arduous quest over years and years of research and trouble. There were issues of negotiating between various film archives preserving the film in different incarnations. There was also the issue that Francis Ford Coppola was also working to restore the film - as he acquired the theatrical rights in the United States. In 1980, more than 10 years of research the 4.5 hour film running at 20 frames per second was as good as it could get for Brownlow. Since the original score was lost, he commissioned composer Carl Davis to create a score for the film. While at the time most silent films were played with random organ music or piano scores, they knew that the reconstructed film needed something as powerful aurally as visually, so it was required to have an orchestra play at the screening rather than a prerecorded soundtrack. Davis worked on the score for 3.5 months and premiered at the National Film Theatre in London in 1980. Crowds and critics were enthralled and amazed by the work - the daring visuals that were unrivaled in the silent era, the use of camera techniques, cutting, and the full orchestra playing the score live. The restored film caused a celebration of interest into silent films again, leading to restorations of more films and interest by the moviegoing public. But the work was far from finished. After the renewed interest, more footage began to be reinstated with newly discovered scenes. The score had to be reworked to fit the new portions. After 20 more years of restoration work, the runtime came to 5.5 hours at the 20fps framerate. While it seems that the 9 hour version of the film is most likely lost forever, this 5.5 hour version collects the most complete version of the film in existence - albeit there are some portions with text accompaniment to explain certain lost scenes. It may never be complete, but regardless of that, the 5.5 hour Brownlow restoration of Abel Gance’s most defining work can be seen by the masses with BFI’s spectacular Blu-ray . Note this is a region B Blu-ray which can only be played back on region B and region free Blu-ray players

Video

BFI presents the restored version of the film in 1080p in the AVC MPEG-4 codec in its original aspect ratio. As stated before the film is in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio for most of the duration of the film. The ending sequence is presented in the 4.00:1 aspect ratio, having large black bars on the top and bottom of the frame. While the film is culminated from a variety of existing source materials, it is impossible to have complete consistency from scene to scene. To explain further, here are some of the restoration notes from BFI (slightly summarized): The restoration of Napoleon on film took place across decades and culminated in a 35mm black and white negative. The print was tinted and toned in the film’s many colours under the supervision of Kevin Brownlow and the BFI National Archive’s then technical manager, Joao Oliveira. Scanning of the negative was carried out using a film gate 8 perforations high - twice the usual 4-perf height. Due to the widely varying historical frameline positions of sections within the negative, scanning in this way was used to ensure no images were cropped even when sequences were in different positions across the 16 reels of negative, totalling more than 26,000ft. The overscan also allowed for stabilisation and alignment to be carried out across the feature, without risk of cropping. The new digital masters of each Act were then created from the scans after stabilisation and deflickering. Image repair and removal of printed in scratches, dirt and other deposits amounted to hundreds of thousands of instances throughout the film. Innumerable fine scratches have been removed or minimised by manual repair work. Those sections of negative unavoidably sourced from reissue prints with a soundtrack area on the left, cropping the original composition, have been centred to better integrate with the full frame majority. The triptych finale of Act 4 has been presented in its original aspect ratio. Minute adjustments to the relative position of each panel (left, centre and right) have allowed for an extremely stable representation. As stated, the amount of hard work reconstructing the film was extensively done and so was in the remastering process. The image is stable throughout, issues such as scratches, dust, and damage have been removed as much as possible, and the finale has been properly synchronized and aligned. It is not perfect by any means. Some scenes look incredibly weak with low definition of figures while the next scene would be sharp as a pin. As inconsistent as it is, it is never extremely distracting. Brownlow’s painstaking work is complimented with the digital technicians who helped bring new life to the 90 year old film. Because of the 5.5 hour runtime, the film has been spread out across three Blu-ray discs: DISC ONE - Act I (113:43) DISC TWO - Acts II & III (170:45) DISC THREE - Act IV - with 4.00:1 finale (48:34)

Audio

Music DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 (48khz/24bit) Music LPCM 2.0 stereo (48khz/24bit) The orchestral score by Carl Davis has been given both a 7.1 channel option or a 2 channel option, which both are identical. Davis’s composition is a mix of original material with classical music of the time period - Bach and Mozart are used as well as the French national anthem, and it sounds incredible. The 7.1 track is a very full track with the surround channels frequently used, bass is deep and instruments are spread out. Surely can be placed as reference quality. Although one thing I would have liked is an option to hear the score as heard at a theatrical screening - like it was done on the “E.T.” 20th Anniversary DVD or on many Robert Rodriguez titles. There are English Intertitles for the feature. The French intertitles are not available on this release, which is unusual for a BFI title. Almost all the titles are newly recreated. Whether this was a rights issue or not it isn’t clear, but for French speakers they will have to wait for a domestic release to see the film in its original language intertitles.

Extras

The film is spread out on three Blu-ray discs, and the extras are as follows: DISC ONE Audio commentary with Paul Cuff Dr. Paul Cuff is the writer of “A Revolution for the Screen: Abel Gance's Napoleon” and gives a 5.5 hour commentary track - possibly a record for a solo audio commentary? Certainly surpasses the 5 hour David Kalat commentary for “Dr. Mabuse - The Gambler”, but may fall short of Oliver Stone doing two separate commentaries for the 3.5 version of “Nixon”. Even with the lengthy time, Cuff is able to talk for the entire duration with very little overlapping material in the process. He is knowledgeable about the real Napoleon and the French Revolution and gives insights into the differences between reality and fiction, extensive notes about Gance and his direction, as well as biographies on the actors. Also mentioned are information about lost scenes or scenes from the shooting script but never filmed, and how the film inspired many other films, especially the children and pillow fight scene being directly homaged in “Zero de conduite” by Jean Vigo and “The 400 Blows” by Francois Truffaut. in English Dolby Digital 2.0 with no subtitles Tryptich Left Panel (21:20) Watching the film’s ending sequence in 4.00:1 means the entire image gets very squished and small. If there was a way to be able to recreate the theatrical experience… And here is the option. Presented on each disc is an individual panel of the 3-panel sequence by itself. All you need is 3 Blu-ray players, 3 projectors, a wall or a screen big enough to project the image, and 3 synchronizers to play the sequence. The center panel is presented in 1.33:1 with black bars on the left and right side. The left panel is presented with a large black bar on the left side and the right panel is presented with a large black bar on the right side. Presented here on the first disc is the left panel. Now the biggest problem besides the logistics? It is with the center panel. Since there are black bars on the side which would be projected, overlapping the images will still create black bars. As the “center projectionist” you would have to manually place filters to project the 1.33:1 image without the black borders. This is more troublesome than The Flaming Lips’ “Zaireeka” album. It’s a lot of hard work, but it is possible! in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33.1, Music DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 / Music LPCM 2.0 stereo with English intertitles DISC TWO Audio commentary with Paul Cuff Dr. Cuff continues with the commentary in the longest portion of the film focusing on the adult years and rise to power. in English Dolby Digital 2.0 with no subtitles Tryptich Centre Panel (21:20) Here is the center portion with the black bars on both sides. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33.1, Music DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 / Music LPCM 2.0 stereo with English intertitles DISC THREE Audio commentary with Paul Cuff Dr. Cuff’s commentary comes to an end with an analysis of the final sequence - the most praised part of the film. in English Dolby Digital 2.0 with no subtitles Tryptich Right Panel (21:20) The right side is presented here. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33.1, Music DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 / Music LPCM 2.0 stereo with English intertitles Single Screen Ending (15:17) The alternate single-screen non-Triptych ending is presented here, which mostly is the same as the center panel. This can be viewed by itself of optionally with the rest of the film via seamless branching, bringing the total runtime for Act IV with 1.33:1 finale as (42:32). in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33.1, Music DTS-HD Master Audio 7.1 / Music LPCM 2.0 stereo with English intertitles "Composing Napoleon" an interview with Carl Davis (45:42) Composer Carl Davis is interviewed here and talks about the scoring of “Napoleon”. He talks about how he met Kevin Brownlow, being given 3.5 months for the score, the learning process, and choices made for the non-original classical pieces. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.78:1, in English LPCM 2.0 with no subtitles "Napoleon Digital Restoration" featurette (4:48) Ben Thompson of BFI, Kevin Brownlow of Photoplay, and Dario Oliver of Dragon give a show behind the scenes look at the digital restoration process. This could have been a full length documentary so the 5 minute runtime feels way too short. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.78:1, in English LPCM 2.0 with no subtitles Stills and Special Collections Gallery (11:29) A collection of behind the scenes photos from the production with captions placing names with faces and additional information are shown in slideshow. Also included are audition photos and the original tour programs, but to a large surprise, there is no music accompaniment at all. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4 "The Charm of Dynamite" documentary (51:34) This BBC TV Documentary on Abel Gance was directed by Kevin Brownlow and aired in 1968. Narrated by Lindsay Anderson, there are extensive clips from “J’accuse” and “La rue” though it basically spoils the whole story for that film. Also included are footage of Gance visiting England in 1965 with interviews and clips of his masterpiece “Napoleon”. Not only does it feature clips from the film, but it also has behind the scenes footage which we can see how intricate and creative the camera setups were and how difficult the shooting was. The documentary has been transferred from the original 16mm film negative and looks wonderful. Scratches are non-existent except for the scenes of the film clips used. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33:1, in English/French LPCM 2.0 with optional English subtitles for the French portions 60 Page Booklet The 60 page booklet includes the following: - “Living History: Abel Gance’s Napoleon” by Paul Cuff - ”My Discovery of Napoleon” by Kevin Brownlow - ”Napoleon on Film: Legend, Prejudice, and Manipulation” by Hervé Dumont - Film Credits - Tour Program - ”Making Music for Napoleon” An interview with Carl Davis by Paul Cuff - Music Credits, Special Features Credits, Restoration Information If you thought Cuff’s commentary was lacking in information on the behind the scenes and pre-production process of the film because he was too busy with what was on screen, here is a good read about some of the hoops Gance had to jump through to get the film made. Brownlow gives his insight into his personal discovery of the film, Dumont recaps the many versions of Napoleon depicted in film which surpasses that of Jesus Christ being depicted in cinema, and the lengthy interview with Davis is an essential read even if you have watched the 45 minute interview as additional information is presented.

Overall

Napoleon Bonaparte is possibly the most legendary historical figure in recent history that continues to inspire, to be studied, to be mocked, and to be despised, and it is that kind of controversy that makes his status grow more with the years that pass. Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” for years has been a nearly mythical film since it was difficult to screen and being incomplete. The BFI’s Blu-ray edition of the 5.5 hour Kevin Brownlow restoration is easily one of the best and most important releases of the year with lengthy in depth extras and having an excellent video and audio transfer.

|

|||||

|