|

|

Hired Hand (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd December 2016). |

|

The Film

The Hired Hand (Peter Fonda, 1971) The Hired Hand (Peter Fonda, 1971)

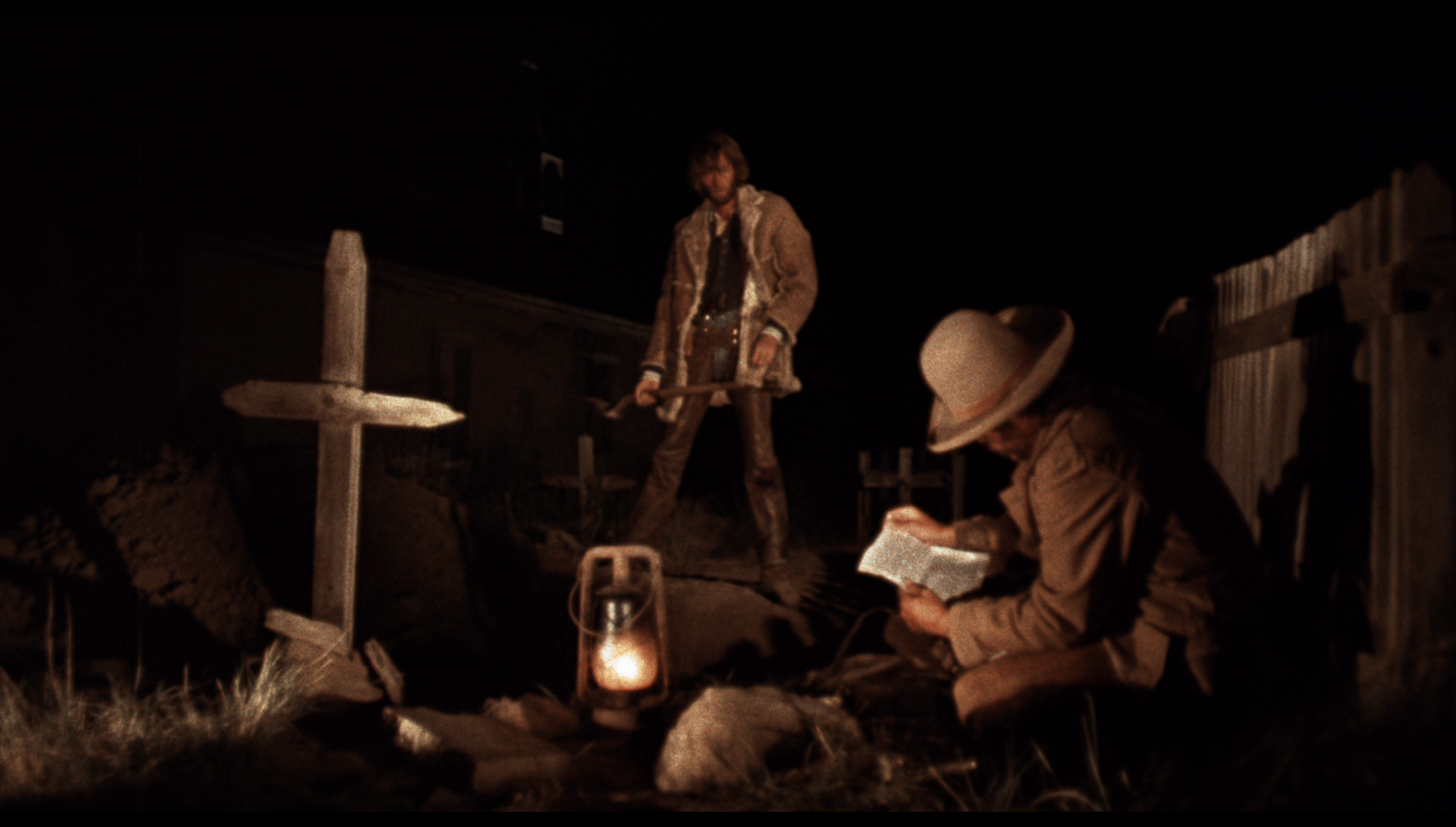

Peter Fonda’s directorial debut, The Hired Hand (1971) opens with three drifters, Harry (Peter Fonda), Archie (Warren Oates) and the younger Dan (Robert Pratt). The three men play and fish in the river, until Dan spots a haunting sight: what seems to be the body of a young girl, caught in the fishing line. Against Dan’s protests, Harry cuts the corpse free and lets it drift with the current away from the men. The three drifters ride into a town, looking for a blacksmith to shoe Dan’s horse. Harry and Archie recognise the town as one they visited three years prior. Dan makes the decision to head for California, and Archie agrees to go with him; but the encounter with the dead child has had an impact on Harry, and he decides instead to return to the house of his estranged wife and the daughter he has never seen. That evening, before the trio part ways, Harry and Archie visit the town’s saloon. They discover that Dan was in there previously and left with a woman. They are shocked when Dan enters the saloon, a bullet wound in his neck and his trousers around his knees. Dan falls to the floor and expires. McVey (Severn Darden), a moderately wealthy landowner, enters and tells the men in the saloon that he shot Dan for ‘attacking’ McVey’s wife. Harry and Archie bury Dan, but having seen through the deveption within McVey’s version of events, Harry plans revenge and the pair ride out to McVey’s homestead. Sneaking up to McVey’s house, Harry shoots through a window and kills one of McVey’s men whilst also wounding McVey’s foot.  Following this, Archie vows to ride with Harry back to the farm owned by Harry’s wife Hannah (Verna Bloom). Hannah has told her daughter, Janey, and the people of the nearby town, that she is a widow. After failing to recognise Harry when he first arrives at the farm, she makes him vow not to tell their daughter that he is her father. Hannah shows little interest in Harry, but grows closer to Archie. She makes overt come-ons to Archie, but mindful of his friend’s love of his family, Archie resists. Following this, Archie vows to ride with Harry back to the farm owned by Harry’s wife Hannah (Verna Bloom). Hannah has told her daughter, Janey, and the people of the nearby town, that she is a widow. After failing to recognise Harry when he first arrives at the farm, she makes him vow not to tell their daughter that he is her father. Hannah shows little interest in Harry, but grows closer to Archie. She makes overt come-ons to Archie, but mindful of his friend’s love of his family, Archie resists.

One day, when he rides into town with Harry for supplies, Archie is confronted by a man in the local saloon. This man insinuates that Hannah is loose in morals: ‘Why, the widow Collings is more than fair [in payment to her hired hands], she’s downright generous [….] Most men who work for the widow Collings get paid in more than just cash and keep’, the man says. In response, at the sleight to Hannah’s reputation and to defend his friend, Archie strikes the man, knocking him to the floor. However, Harry discovers that Hannah has been sleeping with her hired help and, ridden with jealousy, he hangs a series of notices in the town declaring that he, in comparison with what Hannah has suggested, he is not dead and has returned to take his place at the head of the family. This angers Hannah, who wishes to keep from their daughter the fact that Harry is her father. After Hannah’s approaches to Archie become more direct, he makes the decision to leave for California. In Archie’s absence, Harry and Hannah fall back into their respective roles as husband and wife. That is, until one day, when a man on horseback approaches the farm and tells Harry that McVey has caught Archie. The man shows Harry one of Archie’s fingers, which has been severed from Archie’s hand, and tells Harry that with each week that passes, another finger will be taken from Archie – until Harry arrives in McVey’s town for a confrontation. Harry agrees to return to McVey with the man, heading into a confrontation with McVey and his men in the hopes of saving Archie’s life.  Following the success of Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969), in which Peter Fonda essayed the role of Wyatt, Fonda and producer William Hayward encountered in London the script for The Hired Hand. Fonda and Hayward were looking for projects suitable for their new company Pando Productions. The script for The Hired Hand was sent to Fonda and Hayward by Lifton Films, representing the Scottish writer Alan Sharp – who around the same time wrote another strikingly stark, revisionist Western, Robert Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid (1972). (Sharp would go on to write one further Western, Billy Two Hats in 1974, before scripting Arthur Penn’s neo-noir Night Moves in 1975.) Following the success of Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969), in which Peter Fonda essayed the role of Wyatt, Fonda and producer William Hayward encountered in London the script for The Hired Hand. Fonda and Hayward were looking for projects suitable for their new company Pando Productions. The script for The Hired Hand was sent to Fonda and Hayward by Lifton Films, representing the Scottish writer Alan Sharp – who around the same time wrote another strikingly stark, revisionist Western, Robert Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid (1972). (Sharp would go on to write one further Western, Billy Two Hats in 1974, before scripting Arthur Penn’s neo-noir Night Moves in 1975.)

Fonda and Hayward were immediately impressed with Sharp’s script and the sense of authenticity towards the daily life of drifters and proletarian types within the historical west, as opposed to the heroic exploits of cowboys and gunslingers in most Hollywood Westerns. In interview, Hayward commented that ‘Our image of the west has been conditioned by countless television and motion picture versions—and it just didn’t happen that way. In “The Hired Hand,” we felt we had a story that had more legality in it than any western I had ever read. These characters weren’t gunfighters, they were drifters, or as the sheriff calls them, “travellin’ men.” There are strong relevancies to today’s troubled times and the people involved’ (Hayward, quoted in Compo, 2009: np). Initially, Fonda wished to cast himself and Henry Fonda, his father, as the other drifter, Archie Harris (ibid.). In some respects, this film’s emphasis on the gritty authenticity of life in the West for the mostly unremarkable people that lived it seems like an attempt by Fonda to exorcise himself of his father’s roles in earlier Westerns. Warren Oates was known to Fonda, Oates having worked with Henry Fonda in There Was a Crooked Man… (Joseph L Mankiewicz, 1970) and Welcome to Hard Times (Burt Kennedy, 1967). Oates responded warmly to the script, suggesting that The Hired Hand ‘is the America of what Walt Whitman means to me’ (Oates, quoted in ibid.).  Fonda intended to shoot the film in Italy, presumably to capture something of the gritty flavour of the westerns all’italiana that were popular at the time. However, he chose instead to make the picture in New Mexico, shooting the town scenes in Cabezon, a small town of approximately fifteen buildings; founded in the 1870s, Cabezon has functioned as a deserted ‘ghost town’ since the death of Richard Heller, the town’s most prominent citizen and owner of the post office and general store, in 1947. (Ironically, in 1973 Henry Fonda acted in scenes shot in Cabezon for Tonino Valerii’s western all’italiana/‘Spaghetti Western’ Il mio nome e nessuno/My Name is Nobody.) Fonda intended to shoot the film in Italy, presumably to capture something of the gritty flavour of the westerns all’italiana that were popular at the time. However, he chose instead to make the picture in New Mexico, shooting the town scenes in Cabezon, a small town of approximately fifteen buildings; founded in the 1870s, Cabezon has functioned as a deserted ‘ghost town’ since the death of Richard Heller, the town’s most prominent citizen and owner of the post office and general store, in 1947. (Ironically, in 1973 Henry Fonda acted in scenes shot in Cabezon for Tonino Valerii’s western all’italiana/‘Spaghetti Western’ Il mio nome e nessuno/My Name is Nobody.)

In 1971, the film was criticised by critic Molly Haskell for offering ‘a sagebrush “A Doll’s House”’ (Haskell, quoted in Compo, op cit.). Haskell’s allusion to the Ibsen play was perhaps intended to belittle the film, but it is actually quite apt: like the play by Ibsen, The Hired Hand focuses on a theme of marriage and the attitudes towards it, alongside exploring gender roles in society and, especially, the roles of women who step outside those gendered norms of behaviour. Perhaps in response to criticisms leveled against the film, Universal pulled the picture after only one week, Fonda complaining ‘All I’d asked is that people sit still for eighty-three minutes’ (Fonda, quoted in ibid.). Where Fonda had used the success of Easy Rider to make The Hired Hand, Dennis Hopper followed Easy Rider with the impenetrable (and sadly too little-seen) The Last Movie (1971). Both The Last Movie and The Hired Hand are linked, in the words of Norris Pope, by their aspirations to make a Western (in the broad sense) that rose ‘to the level of an art film’ (Pope, 2013: 109). In fact, cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond once suggested that one of the reasons for the negative responses to The Hired Hand’s release was that the picture ‘was too much like a European movie’ (Zsigmond, quoted in ibid.). Sometimes cited as an ‘acid Western’ for its hazy, impressionistic photography and use of lap dissolves to created bizarre, sometimes nightmarish and hallucinatory montages, the completed film was criticised by its writer, Alan Sharp, who asserted that the picture ‘reflected the influences of hallucinogens’ (Sharp, quoted in Compo, op cit.). When the film was shown at the Cinémathèque Française, it was followed by a question and answer session in which Fonda was forced to defend his film’s sense of pace and the use of dissolves in the editing; Fonda later commented that ‘It [the interrogaton] only hurt for a short time […] for we had a case of Dom and some touch’ (Fonda, quoted in ibid.). Screenings elsewhere were hampered by technical problems: printed at the Technicolor lab in London, the film’s third reel was desperately out of focus, leading to the film being excluded from the Circa de Stampa competition in Milan and impacting on a screening in Rome (ibid.). In interviews, Fonda was so dispirited that he began to talk about environmental issues ‘rather than talk about his seemingly sabotaged film. Some thought he had deliberately shot the third reel out of focus’ (ibid.). Screenings in London were impacted by the film being printed in an overexposed manner to such an extreme that Oates told Fonda, who refused to attend a screening owing to fears of it being beset by technical problems, that ‘the only way I could tell it was our movie was the soundtrack, which was perfect’ (Oates, quoted in ibid.).  The moment in which Archie, Harry and Dan encounter the corpse of the little girl floating in the river, the incident which acts as the catalyst for Harry’s decision to return to his own family and the daughter of a similar age who he has never known, is played out entirely via the expressions of the three drifters and their silent responses to what they see offscreen. Close-ups of the men’s faces showing, through their reactions, the horror of the moment are cut against a shot from the perspective of the little girl’s body, looking along the fishing line in which she has been caught to Harry, who is poised with his knife ready to cut the line. In this shot, a wide-angle lens distorts the edges of the frame, reinforcing the extent to which this moment is the major point of disruption in a story that, though comparatively undramatic, has a number of significant disruptions (the death of Dan; the abduction and torture of Archie). The opening moments of the film have been almost idyllic, slow motion photography and lap dissolves depicting the drifters playing in the river and fishing; with the discovery of the girl’s corpse, this moment of camaraderie is undercut brutally by the reality of death. Initially, Harry refuses to concede that the corpse was that of a child: ‘Been dead a while, whatever it was’. However, Dan challenges Harry’s decision to cut the corpse free: ‘It was a little white girl’, Dan asserts desperately. ‘She would’a come to pieces in your hands the moment you started to pull her in’, Harry tells Dan: his decision to allow the corpse to drift away with the tide seems logical, motivated by his reasoning that the presumably decayed corpse would not survive being pulled in on the fishing line; and also by the unstated suggestion that as drifters, if the three men rode into the nearest town bearing the corpse of a child, they would become the objects of suspicion. Still, the moment seems to impress upon Harry the importance of returning to his own family and the daughter he has never seen; like so much in the film, this suggestion is communicated without dialogue, and one of the film’s strengths is its refusal to patronise its audience. The moment in which Archie, Harry and Dan encounter the corpse of the little girl floating in the river, the incident which acts as the catalyst for Harry’s decision to return to his own family and the daughter of a similar age who he has never known, is played out entirely via the expressions of the three drifters and their silent responses to what they see offscreen. Close-ups of the men’s faces showing, through their reactions, the horror of the moment are cut against a shot from the perspective of the little girl’s body, looking along the fishing line in which she has been caught to Harry, who is poised with his knife ready to cut the line. In this shot, a wide-angle lens distorts the edges of the frame, reinforcing the extent to which this moment is the major point of disruption in a story that, though comparatively undramatic, has a number of significant disruptions (the death of Dan; the abduction and torture of Archie). The opening moments of the film have been almost idyllic, slow motion photography and lap dissolves depicting the drifters playing in the river and fishing; with the discovery of the girl’s corpse, this moment of camaraderie is undercut brutally by the reality of death. Initially, Harry refuses to concede that the corpse was that of a child: ‘Been dead a while, whatever it was’. However, Dan challenges Harry’s decision to cut the corpse free: ‘It was a little white girl’, Dan asserts desperately. ‘She would’a come to pieces in your hands the moment you started to pull her in’, Harry tells Dan: his decision to allow the corpse to drift away with the tide seems logical, motivated by his reasoning that the presumably decayed corpse would not survive being pulled in on the fishing line; and also by the unstated suggestion that as drifters, if the three men rode into the nearest town bearing the corpse of a child, they would become the objects of suspicion. Still, the moment seems to impress upon Harry the importance of returning to his own family and the daughter he has never seen; like so much in the film, this suggestion is communicated without dialogue, and one of the film’s strengths is its refusal to patronise its audience.

In these opening scenes, the film emphasises the lack of worldiness and the provincial mindset associated with not just Dan but also Archie and Harry. Dan outlines his plan to go to California, tempted by the oranges, the women and the ocean. ‘They say that ocean looks like a great blue prairie’, Archie says, ‘I ain’t never seen that much water’. Later, Archie tells Harry, ‘He’s [Dan is] always wanting to go someplace he hasn’t been’. Meanwhile, Harry’s encounter with the dead girl has impressed upon him the importance of returning to his family: ‘I ain’t going to the coast’, he tells his companions. ‘Where you gonna go, then?’, Archie asks him. ‘Home’, Harry says. ‘Home? Maybe there ain’t no such colour’, Archie suggests. ‘Home is just a place you start from, Arch’, Harry responds, ‘There’ll be something there’.  In this context, Dan’s death represents a further corruption of innocence and loss of hope; his murder symbolizes the death of his dream of moving to California and what that represents (a movement to a new, more cosmopolitan and enlightened, more rewarding life). Dan has been framed as almost childlike: an adolescent whose lust drives him into the arms of a local woman. He staggers into the saloon after having been shot in the neck by McVey, his trousers hanging around his knees (signifying the fact that McVey has caught Dan mid-coitus), and collapses on the floor. ‘Oh, mother’, he pleads, his words reminding us of his youth. McVey enters and offers a mealy-mouthed explanation for his shooting of the boy, suggesting that Dan was ‘attacking’ McVey’s Mexican wife (whom McVey is later seen abusing) when the words of the saloonkeeper have already made it clear to Archie and Harry that Dan was approached by the woman – who was presumably offering herself for money. This older woman’s seduction of Dan is contextualised within Harry’s own marriage to his wife, who is a decade older than Harry, and the suggestion later in the film that Harry’s wife has essentially paid men to prostitute themselves to her. When Archie asks Harry to describe Hannah, who Harry has not seen in almost ten years and with whom Harry lived for only nine months (presumably leaving before the birth of his daughter), Harry struggles to come up with a firm description: ‘Medium, red hair, brown eyes, I guess’, Harry says, offering a description that the audience will soon see is quite inaccurate, ‘She was thirty when we was married’. ‘How old was you?’, Archie asks. ‘Twenty, just turned’, Harry replies. ‘Hell, boy’, Archie laughs, ‘You didn’t have a chance’. Archie then adds, ‘If I’d had a horse for nine months, I’d sure remember how many teeth it had’. In this context, Dan’s death represents a further corruption of innocence and loss of hope; his murder symbolizes the death of his dream of moving to California and what that represents (a movement to a new, more cosmopolitan and enlightened, more rewarding life). Dan has been framed as almost childlike: an adolescent whose lust drives him into the arms of a local woman. He staggers into the saloon after having been shot in the neck by McVey, his trousers hanging around his knees (signifying the fact that McVey has caught Dan mid-coitus), and collapses on the floor. ‘Oh, mother’, he pleads, his words reminding us of his youth. McVey enters and offers a mealy-mouthed explanation for his shooting of the boy, suggesting that Dan was ‘attacking’ McVey’s Mexican wife (whom McVey is later seen abusing) when the words of the saloonkeeper have already made it clear to Archie and Harry that Dan was approached by the woman – who was presumably offering herself for money. This older woman’s seduction of Dan is contextualised within Harry’s own marriage to his wife, who is a decade older than Harry, and the suggestion later in the film that Harry’s wife has essentially paid men to prostitute themselves to her. When Archie asks Harry to describe Hannah, who Harry has not seen in almost ten years and with whom Harry lived for only nine months (presumably leaving before the birth of his daughter), Harry struggles to come up with a firm description: ‘Medium, red hair, brown eyes, I guess’, Harry says, offering a description that the audience will soon see is quite inaccurate, ‘She was thirty when we was married’. ‘How old was you?’, Archie asks. ‘Twenty, just turned’, Harry replies. ‘Hell, boy’, Archie laughs, ‘You didn’t have a chance’. Archie then adds, ‘If I’d had a horse for nine months, I’d sure remember how many teeth it had’.

For her part, Hannah is unrepentant about the fact that she has slept with her hired hands; her use of these men, who are in her pay, for her sexual gratification turns the usual stereotypes about male-female relations on their head, justifying Molly Haskell’s comparison of the film with the Ibsen play. Where the woman who approaches Dan prostitutes herself to the young man, Hannah asks her labourers to prostitute themselves to her; in doing so, she separates love and sex, suggesting sex is simply a physical need that can be satisfied outside the context of a loving relationship. When Harry learns about the fact that Hannah has been sleeping with the hired hands on her farm, he confronts her. ‘You were long gone before anybody got into my bed’, Hannah tells him, ‘I’d already had one man in here and I didn’t want another’. Later, in an attempt at seduction she tells Archie of her ‘conquests’: ‘Out in the field or in the hay, or sometimes just down in the dirt [….] Wouldn’t matter if it was you or him tonight’. However, Archie shows himself to be in control of his impulses, rejecting Hannah gently.  When Harry and Archie arrive at Hannah’s farm, Hannah fails to recognise Harry. When he (re)introduces himself to her, she asks him why he has ‘come back’. ‘Got tired of the life’, he says simply, ‘Just let me work the place for a bit, like a hired hand’. Hannah tells Harry that their daughter believes her father to be dead and ‘I don’t want you saying no different’. She makes Harry and Archie sleep in the barn. Hannah shows more interest in Archie than in Harry, though Harry seems oblivious to this. In their conversations, filled with subtle innuendo and illustrated with longing looks from Hannah to Archie and vice versa, Hannah hints at her dissatisfaction with Harry. ‘How come you don’t have a dog?’, Archie asks. ‘Had one but it ran away’, Hannah replies, ‘Never bothered to get another’. Hannah’s use of indirect speech hints at but does not state overtly her bitterness towards Harry. Later, she asks Archie why he followed Harry: ‘What are you getting out of this, Mr Harris?’, she queries. ‘If I wasn’t doing this, I’d be doing something else’, Archie responds, ‘Me and Harry rid around for a while. He’s keen to try this, so I thought I’d tag along’. ‘He’ll go’, Hannah says, deadly sure that Harry will eventually abandon her and their daughter once again, ‘It’s just a matter of time’. ‘Most things are, one way or another’, Archie responds. However, it’s Archie that leaves; when Archie makes plans to depart for California, Hannah expresses jealousy regarding Archie and Harry’s close friendship. ‘That man out there. He’s a decent man, I’m sure. But he’s had more of you than I have’, Hannah tells her husband, referring to Archie. She suggests that a male friend is ‘easier to please’ than a woman, telling Harry that bringing Archie to the farm is ‘just like you came home with some woman you’d been living with and said, “I want her to stay in the spare room”’. In response, Harry informs Hannah of the hardships involved in living as a drifter: ‘Out there where he’s [Archie is] going, Hannah, it’s cold on your own’. When Harry vows to ride out to meet McVey and hopefully rescue Archie, Hannah protests: ‘I don’t care about him [Archie]. I care about me and Janey and you [….] You planned it, the two of you. You never meant to stay [….] You won’t come back, I know it’. When Harry and Archie arrive at Hannah’s farm, Hannah fails to recognise Harry. When he (re)introduces himself to her, she asks him why he has ‘come back’. ‘Got tired of the life’, he says simply, ‘Just let me work the place for a bit, like a hired hand’. Hannah tells Harry that their daughter believes her father to be dead and ‘I don’t want you saying no different’. She makes Harry and Archie sleep in the barn. Hannah shows more interest in Archie than in Harry, though Harry seems oblivious to this. In their conversations, filled with subtle innuendo and illustrated with longing looks from Hannah to Archie and vice versa, Hannah hints at her dissatisfaction with Harry. ‘How come you don’t have a dog?’, Archie asks. ‘Had one but it ran away’, Hannah replies, ‘Never bothered to get another’. Hannah’s use of indirect speech hints at but does not state overtly her bitterness towards Harry. Later, she asks Archie why he followed Harry: ‘What are you getting out of this, Mr Harris?’, she queries. ‘If I wasn’t doing this, I’d be doing something else’, Archie responds, ‘Me and Harry rid around for a while. He’s keen to try this, so I thought I’d tag along’. ‘He’ll go’, Hannah says, deadly sure that Harry will eventually abandon her and their daughter once again, ‘It’s just a matter of time’. ‘Most things are, one way or another’, Archie responds. However, it’s Archie that leaves; when Archie makes plans to depart for California, Hannah expresses jealousy regarding Archie and Harry’s close friendship. ‘That man out there. He’s a decent man, I’m sure. But he’s had more of you than I have’, Hannah tells her husband, referring to Archie. She suggests that a male friend is ‘easier to please’ than a woman, telling Harry that bringing Archie to the farm is ‘just like you came home with some woman you’d been living with and said, “I want her to stay in the spare room”’. In response, Harry informs Hannah of the hardships involved in living as a drifter: ‘Out there where he’s [Archie is] going, Hannah, it’s cold on your own’. When Harry vows to ride out to meet McVey and hopefully rescue Archie, Hannah protests: ‘I don’t care about him [Archie]. I care about me and Janey and you [….] You planned it, the two of you. You never meant to stay [….] You won’t come back, I know it’.

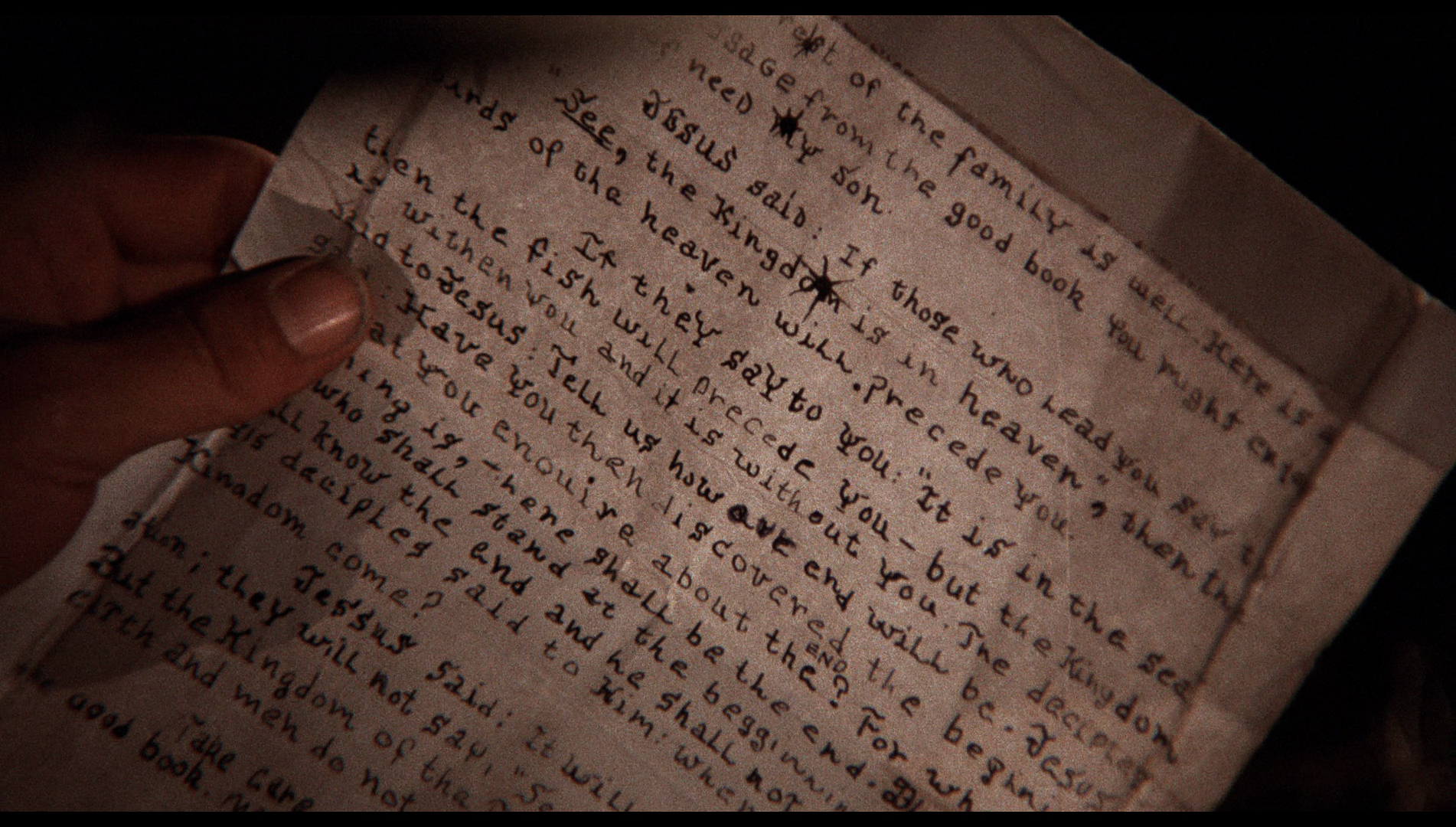

When Harry and Archie bury Dan, Archie reads a passage from the Gospel of Thomas, ending with the assertion that ‘The kingdom of the Father is spread upon the earth, and men do not see it’. Although anachronistic (the Gospel of Thomas was only discovered in 1945), the passage was chosen owing to the fact that it expressed what he felt was a key theme of the film: the lack of awareness by the characters as to how beautiful the world around them is, and the juxtaposition of man’s cruelty with the natural world. Another passage from the Gospel of John has even more relevance for the film, and especially Harry’s relationship with his family and Archie: ‘The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. The hired hand is not the shepherd who owns the sheep. So when he sees the wolf coming, he abandons the sheep and runs away. Then the wolf attacks the flock and scatters it. The man runs away because he is a hired hand and cares nothing for the sheep. “I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me […] and I lay down my life for the sheep”’. One might say that the narrative depicts Harry’s transition from being a hired hand (who cares nothing for the flock – his family – and abandons them) into the ‘good shepherd’ who will ‘lay down his life for the sheep’.

Video

Taking up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Arrow’s 1080p presentation of The Hired Hand uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 91:12 mins, and presented in its original screen ratio of 1.85:1. A longer television version was assembled for broadcast on NBC-TV in 1973; the scenes that are exclusive to that television cut of the film (including footage featuring Larry Hagman as the sheriff of the town near Hannah’s farm) are presented on this Blu-ray disc as ‘extra’ features. Taking up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Arrow’s 1080p presentation of The Hired Hand uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 91:12 mins, and presented in its original screen ratio of 1.85:1. A longer television version was assembled for broadcast on NBC-TV in 1973; the scenes that are exclusive to that television cut of the film (including footage featuring Larry Hagman as the sheriff of the town near Hannah’s farm) are presented on this Blu-ray disc as ‘extra’ features.

Amazingly, given the quiet confidence within the film’s photography, this was the first major feature shot by legendary cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond. (Zsigmond also lensed Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller in the same year.) Zsigmond’s photography is made even more haunting by the use of the lap dissolves employed by editor Frank Mazzolla, whose non-linear work can be seen in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970), and in Cammell’s Demon Seed (1977) and the ‘director’s cut’ of Cammell’s Wild Side (1995). The Hired Hand was short largely on the still relatively new lightweight Arriflex 35mm camera, the mobility of this camera enabling Zsigmond to capture ‘the film’s extraordinary lovely sunset and evening shots’ (Pope, op cit.: 109). Fonda later reflected that the ‘normal procedure’ during the shoot ‘was to call a wrap for the day, wait until… the rest of the cast and crew had disappeared, and then take out Vilmos’ Arriflex [to] shoot late evening shots’ (Fonda, quoted in ibid.). Almost all of the film, barring one sequence, was shot on location, and the lightweight Arriflex was used extensively – handheld, on horseback, and mounted to a station wagon (see ibid.: 110). Quite a lot of the photography, including the opening sequence, uses contre-jour shooting – shooting against the sunlight to render the subject in silhouette against the bright sun.  This presentation is remarkable, given the technical problems that plagued the film when it was first released (see the main body of the review above), with the third reel being printed out of focus and the London screenings being hampered by the fact that the prints were reputedly hugely overexposed. The film was restored in the early 2000s, using the film’s original negative as its source; the restoration was overseen by the film’s editor Frank Mazzola (who suggested that the negative was damaged by approximately 65%) and featured input from Peter Fonda, and when complete it was shown at a number of festivals (see Crust, 2003: np). That restoration eventually made its way to DVD via the Sundance Channel (in the US) and Tartan Video (in the UK). This presentation is remarkable, given the technical problems that plagued the film when it was first released (see the main body of the review above), with the third reel being printed out of focus and the London screenings being hampered by the fact that the prints were reputedly hugely overexposed. The film was restored in the early 2000s, using the film’s original negative as its source; the restoration was overseen by the film’s editor Frank Mazzola (who suggested that the negative was damaged by approximately 65%) and featured input from Peter Fonda, and when complete it was shown at a number of festivals (see Crust, 2003: np). That restoration eventually made its way to DVD via the Sundance Channel (in the US) and Tartan Video (in the UK).

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release is based on the restoration supervised by Mazzolam the HD master provided by NBC Universal. The inventive and unusual photography outlined above – with its use of overlapping images, the emphasis on contre-jour shooting and the deliberately hazy, soft-focus appearance of many scenes – is communicated beautifully on this HD presentation. There is lots of play within the photography with focus and depth of field: for example, the film’s opening shot is a deliberately out of focus shot of the sky, which tilts down to a hazy, diffuse image of Harry and Dan by the river – Dan playing in the water like a child, whilst Harry fishes with is line. It’s a film with a very dreamlike, impressionistic aesthetic, whilst the colour palette is dominated by drab browns, greys and blacks – giving the depiction of the West a very gritty, dirty appearance. Images of photographic clarity are juxtaposed with obscured, hazy shots. (The screen grabs used throughout this review, and the large screen grabs at the bottom of the review, should illustrate this.) Colour reproduction is very strong, and contrast levels are equally pleasing – evident especially in the contre-jour shots and the interiors, which feature balanced midtones and strong shadows. Finally, a good encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. The Tartan Video DVD release of the restoration was very pleasing for its time, but Arrow’s Blu-ray disc – whilst based on the same source – offers a significant improvement, especially in the nighttime scenes.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track. This is rich, deep and clear. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: -  An audio commentary with Peter Fonda. This is the same commentary that was recorded for the film’s previous DVD releases. Fonda is a warm commentator, his reflections of the film’s production made vivid through his use of anecdotes. An audio commentary with Peter Fonda. This is the same commentary that was recorded for the film’s previous DVD releases. Fonda is a warm commentator, his reflections of the film’s production made vivid through his use of anecdotes.

- ‘The Return of the Hired Hand’ (58:47). This 2003 documentary was included in the film’s DVD releases. Taking a look back at the production of the film, the documentary includes comments from Fonda, Mazzola, Zsigmond, the film’s composer Bruce Langhorne, Bloom, production designer Lawrence G Paull. Fonda explains why he chose to make a Western, suggesting he was motivated by a desire to tell ‘the truth of what went down in the West’. As with Easy Rider, the picture was an attempt to help Fonda leave ‘the shadow that my father cast’. The participants reflect on the choice to shoot the film in the ghost town of Cabezon, and Fonda comments on the choices made during the casting process. Langhorne’s score for the picture is discussed at length. The problems that accompanied the film’s release are also examined, with Fonda reflecting on the initial response to the film, which he suggests ‘was coloured by the incredible response to Easy Rider’: the audience expected to see Fonda atop a motorcycle rather than a horse, and thus didn’t connect with The Hired Hand. The television edit is discussed, with Fonda complaining that this version of the picture omitted much of the storyline. The decision to restore the film is explored, and Mazzola discusses some of the processes involved in doing this, and the ways in which the film found a new audience because, Fonda suggests, new viewers ‘have forgotten all about Captain America’. - Deleted Scenes: o ‘Barkeep Innuendo’ (1:16). o ‘Dumb Animals, Horses’ (2:21). o ‘Morning After’ (1:41). o ‘Lookin’ for Work’ (4:51). o ‘Saloon School’ (9:54). o ‘Gunfight’ (alternate ending) (3:19). These deleted scenes are all taken from the NBC television edit of the picture, and are presented here in the 1.33:1 ratio. They seem to be sourced from a videotape recording of this edit of the film. The most extensive of the deleted scenes is ‘Saloon School’, which features Larry Hagman in the role of the town’s sheriff. (Hagman’s sheriff is completely absent from Fonda’s preferred cut of the film.) -  ‘The Odd Man’ (51:59). In this documentary from 1978, the work of three Scottish writers – Edward Boyd, Gordon Williams and Alan Sharp – is examined. These three writers reflect on their quite disparate work. It’s a fascinating archival piece which features plenty of input from the writers themselves. Shot on 16mm, it’s presented in its broadcast ratio of 1.33:1. ‘The Odd Man’ (51:59). In this documentary from 1978, the work of three Scottish writers – Edward Boyd, Gordon Williams and Alan Sharp – is examined. These three writers reflect on their quite disparate work. It’s a fascinating archival piece which features plenty of input from the writers themselves. Shot on 16mm, it’s presented in its broadcast ratio of 1.33:1.

- Interview with Martin Scorsese (2:01). This also appeared on the film’s DVD releases from the early 2000s. Scorsese discusses the context of the film’s production and suggests that though at the time of its release it may have been called an ‘anti-Western’, looking at the film today ‘it seems more like a classic example of the genre’. - Warren Oates and Peter Fonda at the NFT (76:52). This audio recording of Oates and Fonda, interviewed at the NFT in 1971, was made ahead of the UK release of The Hired Hand. The pair are on very good form, fielding questions from the audience and discussing the production of the film and the logistics of producing and releasing a picture such as this. Some of the audience’s questions are quite difficult to make out, but Oates and Fonda’s responses are clear enough. - Stills Gallery (30 images). - Trailers: Trailer 1 (1:26); Trailer 2 (0:53); Trailer 3 (2:33); Trailer 4 (2:01). - TV Spots: TV Spot 1 (1:02); TV Spot 2 (0:32); TV Spot 3 (0:23); TV Spot 4 (0:13). - Radio Spots: Radio Spot 1 (0:44); Radio Spot 2 (0:28); Radio Spot 3 (0:28); Radio Spot 4 (0:11). One of Arrow’s beautiful booklets is included. Illustrated with images from the film, the booklet contains a ‘cast and crew’ page and a new essay about the film, ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ by Kim Morgan. Opening with a quote from Oates and a second quote from Fonda, the essay focuses on the shooting of the film, exploring its context as a post-Easy Rider production and its emphasis on the family unit. Morgan’s essay ends with a personal anecdote regarding Fonda.

Overall

A gritty, grubby Western, The Hired Hand takes its time to build up a strong sense of atmosphere. Haskell’s comparison of the film with Ibsen’s The Doll’s House is very apt in highlighting Fonda’s film’s focus on the family and gender roles. It’s definitely a film that provokes strong reactions, with viewers either loving it or loathing it. Its slow pace is a barrier to some; to others, this is one of the film’s strengths. Certainly, the film offers an atypical depiction of the West – a place populated by drifters, where weapons are inaccurate and clumsy, and where violence is swift and death sudden. Though the label ‘acid Western’ fits somewhat owing to Zsigmond’s often dreamlike imagery, Fonda’s picture fits neatly into the numerous revisionist Westerns made during the beginning of the 1970s, from Frank Perry’s Doc (1971) and Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971) to Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1972) and Robert Benton’s Bad Company (1972). Like most of these revisionist Westerns, The Hired Hand may be deeply divisive, but its treatment here is undeniably impressive. Based on the same restoration that was released on DVD early in the 2000s, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of this picture contains a very pleasing presentation of the film and a strong range of contextual material. It's a release that is sure to please fans of the film. A gritty, grubby Western, The Hired Hand takes its time to build up a strong sense of atmosphere. Haskell’s comparison of the film with Ibsen’s The Doll’s House is very apt in highlighting Fonda’s film’s focus on the family and gender roles. It’s definitely a film that provokes strong reactions, with viewers either loving it or loathing it. Its slow pace is a barrier to some; to others, this is one of the film’s strengths. Certainly, the film offers an atypical depiction of the West – a place populated by drifters, where weapons are inaccurate and clumsy, and where violence is swift and death sudden. Though the label ‘acid Western’ fits somewhat owing to Zsigmond’s often dreamlike imagery, Fonda’s picture fits neatly into the numerous revisionist Westerns made during the beginning of the 1970s, from Frank Perry’s Doc (1971) and Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971) to Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1972) and Robert Benton’s Bad Company (1972). Like most of these revisionist Westerns, The Hired Hand may be deeply divisive, but its treatment here is undeniably impressive. Based on the same restoration that was released on DVD early in the 2000s, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of this picture contains a very pleasing presentation of the film and a strong range of contextual material. It's a release that is sure to please fans of the film.

References: Compo, Susan A, 2009: Warren Oates: A Wild Life. The University Press of Kentucky Crust, Kevin, 2003: ‘“Hired Hand” gets another chance’. Los Angeles Times (20 October, 2003) Pope, Norris, 2013: Chronicle of a Camera: The Arriflex 35 in North America, 1945-1972. University Press of Mississippi

|

|||||

|