|

|

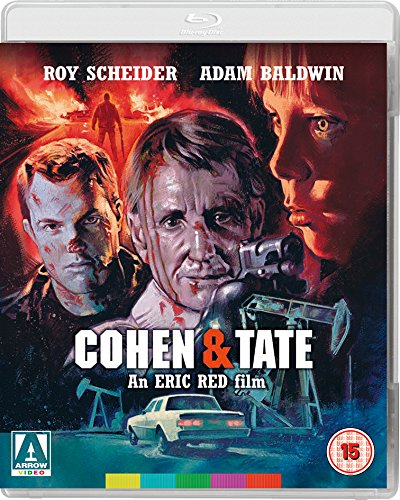

Cohen & Tate (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th December 2016). |

|

The Film

Cohen & Tate (Eric Red, 1988) Cohen & Tate (Eric Red, 1988)

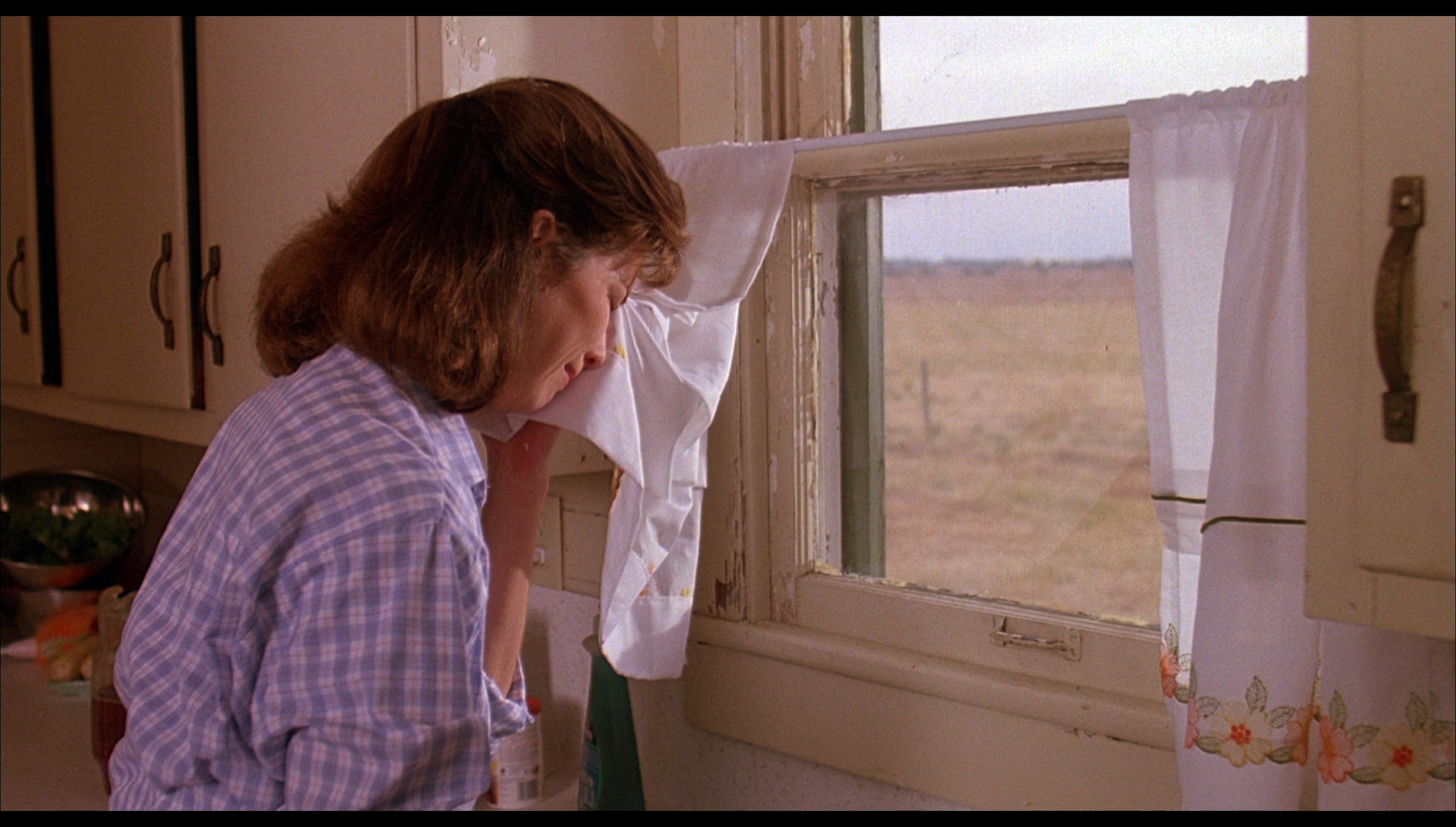

Nine year old Travis Knight (Harley Cross), a witness to a mob hit, is with his family in protective custody. The Knights are being kept in a farmhouse in Muskogee, guarded by three FBI agents. However, it seems that one of the FBI agents, George (Marco Perella), has betrayed the Knights, giving their location to the mob. When George flees, the remaining two FBI agents become suspicious – as do Travis’ parents. During the evening meal, Travis’ dog Biggy runs from the house; Travis follows his beloved pet. Worried for his son’s life, Travis’ father (Cooper Huckabee) attempts to follow but is stopped by the FBI agent guarding the Knights. Meanwhile, the FBI agent guarding the outside of the house is shown to have been killed. As Travis searches outside for Biggy, hired killers Cohen (Roy Scheider) and Tate (Adam Baldwin) storm the farmhouse. Using a high powered shotgun, Tate kills the remaining FBI agent and shoots Travis’ father. Meanwhile, Cohen has caught Travis, returning the boy to the farmhouse – where Travis witnesses Tate shooting and killing Travis’ mother. Cohen chastises Tate for the overkill in his use of the shotgun; he and Tate seize Travis, with the intention of driving him overnight to Houston, where the child is to be questioned and most likely executed by the members of the ‘mob’ who have hired the two killers. During the night, Travis tries to escape before realising that his best chance of survival is to pit killer against killer.  Having established what would evolve into a longstanding fascination with the outlaw on the fringes of society in his first feature scripts (for Robert Harmon’s The Hitcher, 1986, and Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark, 1987), Eric Red wrote and directed Cohen & Tate (1988) in forty-five days, on location and for $5.5 million. Like The Hitcher, Cohen & Tate features a situation, most of which takes place in a moving car, in which a young man is tormented by a relentless, unhinged killer. However, Cohen & Tate amplifies the dramatic potential of this basic premise by reducing the age of the protagonist (C Thomas Howell’s character in The Hitcher was in his early 20s; the young protagonist of Cohen & Tate is only nine years old) and increasing the number of killers (Rutger Hauer’s murderous hitcher worked very much by himself, but in Cohen & Tate the protagonist is terrorised by the two titular hired guns). As if to further reinforce the sense that Cohen & Tate is an amped-up version of The Hitcher, the two films feature some similar narrative events: for example, in one sequence in Cohen & Tate, Travis manages to escape from Cohen and Tate, seeking help from a highway patrol officer, only for this officer to be killed by the hired guns; likewise, in The Hitcher C Thomas Howell’s encounters with law enforcement personnel ultimately end in these police officers being murdered by Rutger Hauer’s hitchhiker. In both pictures, the fact that members of law enforcement are ‘got at’ by the films’ respective antagonists amplifies the sense of danger through suggesting that the protagonists are not even safe when in the care of figures of authority. Both films offer a combination of the iconography of the road movie (constant movement from one destination to another) and the inner form/themes of the chiller. James Monaco has suggested that ‘[s]ome of the most interesting films of the 1980s offer a heady mix of a B-movie ethos, a focus on unpleasant people in unpleasant situations, disturbing undercurrents, and haunting imagery’ (Monaco, 1992: 141). Cohen & Tate is a film that offers all of these paradigms (ibid.). Having established what would evolve into a longstanding fascination with the outlaw on the fringes of society in his first feature scripts (for Robert Harmon’s The Hitcher, 1986, and Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark, 1987), Eric Red wrote and directed Cohen & Tate (1988) in forty-five days, on location and for $5.5 million. Like The Hitcher, Cohen & Tate features a situation, most of which takes place in a moving car, in which a young man is tormented by a relentless, unhinged killer. However, Cohen & Tate amplifies the dramatic potential of this basic premise by reducing the age of the protagonist (C Thomas Howell’s character in The Hitcher was in his early 20s; the young protagonist of Cohen & Tate is only nine years old) and increasing the number of killers (Rutger Hauer’s murderous hitcher worked very much by himself, but in Cohen & Tate the protagonist is terrorised by the two titular hired guns). As if to further reinforce the sense that Cohen & Tate is an amped-up version of The Hitcher, the two films feature some similar narrative events: for example, in one sequence in Cohen & Tate, Travis manages to escape from Cohen and Tate, seeking help from a highway patrol officer, only for this officer to be killed by the hired guns; likewise, in The Hitcher C Thomas Howell’s encounters with law enforcement personnel ultimately end in these police officers being murdered by Rutger Hauer’s hitchhiker. In both pictures, the fact that members of law enforcement are ‘got at’ by the films’ respective antagonists amplifies the sense of danger through suggesting that the protagonists are not even safe when in the care of figures of authority. Both films offer a combination of the iconography of the road movie (constant movement from one destination to another) and the inner form/themes of the chiller. James Monaco has suggested that ‘[s]ome of the most interesting films of the 1980s offer a heady mix of a B-movie ethos, a focus on unpleasant people in unpleasant situations, disturbing undercurrents, and haunting imagery’ (Monaco, 1992: 141). Cohen & Tate is a film that offers all of these paradigms (ibid.).

The narrative is compressed into a single night: Cohen and Tate’s assault on the rural hideaway of Travis’ family takes place in the afternoon, and the final sequence of the film sees the dawn of the next day. This compressed, claustrophobic approach to storytelling might remind the viewer of the work of a lean, hardboiled ‘B’ noir director such as Don Siegel or Phil Karlson. In interview, Red suggested that Cohen & Tate originated in his fascination with ‘the whole concept of doing a tight little road picture, but a night one. The whole concept came really from the idea of two hitmen who kidnap a little kid and the possibilities in the conflict of the kid turning them against each other to survive, until the killers do what they do best and kill one another. I like taking—then and now—just a few characters and putting them in a contained psychological conflict situation. The key for me is a clean mano a mano confrontation’ (Red, quoted in Kane & O’Regan, 2011: 175). The narrative is compressed into a single night: Cohen and Tate’s assault on the rural hideaway of Travis’ family takes place in the afternoon, and the final sequence of the film sees the dawn of the next day. This compressed, claustrophobic approach to storytelling might remind the viewer of the work of a lean, hardboiled ‘B’ noir director such as Don Siegel or Phil Karlson. In interview, Red suggested that Cohen & Tate originated in his fascination with ‘the whole concept of doing a tight little road picture, but a night one. The whole concept came really from the idea of two hitmen who kidnap a little kid and the possibilities in the conflict of the kid turning them against each other to survive, until the killers do what they do best and kill one another. I like taking—then and now—just a few characters and putting them in a contained psychological conflict situation. The key for me is a clean mano a mano confrontation’ (Red, quoted in Kane & O’Regan, 2011: 175).

The narrative leanness is signposted by the film’s use of a couple of onscreen title cards at its front-end; these onscreen titles outline pithily the reasons why Cohen and Tate have been sent for Travis. The film wastes no time establishing exactly what Travis witnessed or who precisely hired Cohen and Tate to find him, or for that matter why the lone wolf Cohen has been paired with Tate. The onscreen title cards simply tell us that Travis Knight, nine years old, witnessed a murder and is in protective custody with his family; the (undefined) ‘mob’ want to silence him. Some, especially those conditioned by modern Hollywood fare, might find this lack of detailed ‘backstory’ unsatisfying; but it arguably turns the film into an existentialist fable, in the manner of (for example) a Sam Peckinpah picture, in which characters are defined by their actions. (‘I don’t care what you meant to do’, the ill-fated bank manager at the start of Peckinpah’s 1969 Western The Wild Bunch tells his staff, ‘It’s what you did I don’t like’.)  In its focus on a child in peril, Cohen & Tate seemed like the culmination of a decade in which a number of films had explored this theme, from adventure-themed children’s pictures such as The Goonies (Richard Donner, 1985) to more adult slasher-themed films like Dick Richard’s Death Valley (1982), in which a young boy, Billy (Peter Billingsley), whose exploration into a seemingly abandoned RV results in Billy finding a key piece of evidence in a murder. Billy thus unwittingly inspires the ire of a serial killer who pursues Billy and his divorcee mother with the aim of silencing the boy. Released in January of 1989, Cohen & Tate was complemented the following year by Chris Columbus’ Home Alone (1990), which plays a similar situation (an eight year old boy, Kevin McAllister, left to defend himself against two hardened criminals) for laughs and features an arguably equal amount of violence as Eric Red’s film – but with this violence manifesting itself as slapstick, directed by Kevin against the ‘Wet Bandits’, Harry (Joe Pesci) and Marv (Daniel Stern). Both Home Alone and Cohen & Tate seem to have shared roots in the famous 1907 story by O Henry, ‘The Ransom of Red Chief’, in which two men plot to kidnap and ransom a wealthy man’s ten year old son only to discover that the child is too much to handle – and the kidnappers are forced to pay the father before they can return the child to his parents. In its focus on a child in peril, Cohen & Tate seemed like the culmination of a decade in which a number of films had explored this theme, from adventure-themed children’s pictures such as The Goonies (Richard Donner, 1985) to more adult slasher-themed films like Dick Richard’s Death Valley (1982), in which a young boy, Billy (Peter Billingsley), whose exploration into a seemingly abandoned RV results in Billy finding a key piece of evidence in a murder. Billy thus unwittingly inspires the ire of a serial killer who pursues Billy and his divorcee mother with the aim of silencing the boy. Released in January of 1989, Cohen & Tate was complemented the following year by Chris Columbus’ Home Alone (1990), which plays a similar situation (an eight year old boy, Kevin McAllister, left to defend himself against two hardened criminals) for laughs and features an arguably equal amount of violence as Eric Red’s film – but with this violence manifesting itself as slapstick, directed by Kevin against the ‘Wet Bandits’, Harry (Joe Pesci) and Marv (Daniel Stern). Both Home Alone and Cohen & Tate seem to have shared roots in the famous 1907 story by O Henry, ‘The Ransom of Red Chief’, in which two men plot to kidnap and ransom a wealthy man’s ten year old son only to discover that the child is too much to handle – and the kidnappers are forced to pay the father before they can return the child to his parents.

Cohen and Tate’s fractious relationship and uneasy alliance manifests itself in Cohen’s disapproval of Tate’s methods. As played by Adam Baldwin, Tate is a relentless lover of violence – similar in many ways to Baldwin’s role as Animal Mother in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1989). As played by Scheider, Cohen is a seasoned professional hitman, accustomed to working alone; dressed smartly, his vulnerability is signified through his use of a hearing aid. On the other hand, Tate’s leather jacket symbolises his youth and his status as a ‘hothead’ – something that is emphasised through the childish tantrums he experiences throughout the film when things don’t go as planned. Tate is seen throughout the film carrying a large combat shotgun, this weapon contrasted with the easily-concealed pistol that Cohen prefers. After their assault on the farmhouse in which the FBI were hiding the Knights, Cohen chastises Tate for the level of overkill, especially his use of multiple shells fired from the shotgun to kill Travis’ mother (in front of the child’s eyes). ‘How come you been giving me shit since we left Houston?’, Tate asks his partner. ‘Because I don’t like you’, Cohen replies, ‘You’re a stupid, sloppy hothead. You used six cartridges on the woman and the FBI, when two would have done it, just because you like the sight of blood. You’re a half-ass who’s got no business working with me’. Cohen and Tate’s fractious relationship and uneasy alliance manifests itself in Cohen’s disapproval of Tate’s methods. As played by Adam Baldwin, Tate is a relentless lover of violence – similar in many ways to Baldwin’s role as Animal Mother in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1989). As played by Scheider, Cohen is a seasoned professional hitman, accustomed to working alone; dressed smartly, his vulnerability is signified through his use of a hearing aid. On the other hand, Tate’s leather jacket symbolises his youth and his status as a ‘hothead’ – something that is emphasised through the childish tantrums he experiences throughout the film when things don’t go as planned. Tate is seen throughout the film carrying a large combat shotgun, this weapon contrasted with the easily-concealed pistol that Cohen prefers. After their assault on the farmhouse in which the FBI were hiding the Knights, Cohen chastises Tate for the level of overkill, especially his use of multiple shells fired from the shotgun to kill Travis’ mother (in front of the child’s eyes). ‘How come you been giving me shit since we left Houston?’, Tate asks his partner. ‘Because I don’t like you’, Cohen replies, ‘You’re a stupid, sloppy hothead. You used six cartridges on the woman and the FBI, when two would have done it, just because you like the sight of blood. You’re a half-ass who’s got no business working with me’.

As the narrative progresses, it becomes clear that Cohen, who is coming to the end of his career, distrusts Tate because it’s been made clear to him that retiring isn’t an option – and he may have been paired with Tate so that Tate may execute Cohen. ‘In this business, you don’t retire’, Cohen asserts, ‘They don’t give you any social security, and you don’t get a gold watch. What you do get one day, when you’re not looking, is a brief pain in the back of your head and a quick glimpse of your brains flying out before they scrape you up off the sidewalk’. Perhaps because of his distrust of Tate, Cohen begins to display some sympathy towards Travis. When Tate threatens Travis’ life, saying he would prefer to kill the child than deliver him to the mob in Houston, Cohen intervenes: ‘We’re being paid to deliver this kid in one piece’, he reminds Tate, ‘That means no marks on him’.  Tate’s unpredictable behaviour lends a real sense of suspense to a sequence in which Cohen and Tate’s car becomes caught in a police roadblock. The pair wait for the police officers to approach their car before pulling their guns on the officers and demanding they let them through the roadblock. Tate amplifies the situation by indicating towards the car in front of that driven by Cohen, out of the rear window of which is a smiling baby. Tate grins broadly towards the child, pointing his shotgun at it and suggesting clearly to the police officer that if the officer doesn’t do as Tate demands, Tate will kill the child; having seen Tate’s overkill in the assault on Travis’ family, at this point in the film the viewer will most likely believe that Tate may carry through with his threat. However, despite the threat that Tate represents, when Travis quietly mutters ‘Kill him, Mr Cohen’, the moment is still utterly shocking owing to the connotations of what the child is saying. Seemingly unsure what to do with this potent combination of child-in-peril narrative and brutal violence, Orion struggled to release the film properly and it didn’t really find an audience until it was released on videotape. Tate’s unpredictable behaviour lends a real sense of suspense to a sequence in which Cohen and Tate’s car becomes caught in a police roadblock. The pair wait for the police officers to approach their car before pulling their guns on the officers and demanding they let them through the roadblock. Tate amplifies the situation by indicating towards the car in front of that driven by Cohen, out of the rear window of which is a smiling baby. Tate grins broadly towards the child, pointing his shotgun at it and suggesting clearly to the police officer that if the officer doesn’t do as Tate demands, Tate will kill the child; having seen Tate’s overkill in the assault on Travis’ family, at this point in the film the viewer will most likely believe that Tate may carry through with his threat. However, despite the threat that Tate represents, when Travis quietly mutters ‘Kill him, Mr Cohen’, the moment is still utterly shocking owing to the connotations of what the child is saying. Seemingly unsure what to do with this potent combination of child-in-peril narrative and brutal violence, Orion struggled to release the film properly and it didn’t really find an audience until it was released on videotape.

Video

Taking up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Cohen & Tate is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The HD master was provided by MGM and seems identical to the one used for the film’s Blu-ray release in America by Shout! Factory. Taking up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Cohen & Tate is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The HD master was provided by MGM and seems identical to the one used for the film’s Blu-ray release in America by Shout! Factory.

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. It’s the uncut MPAA ‘R’ rated version, with a running time of 86:02 mins. (The scenes deleted from the film to avoid an ‘X’ rating – the massacre of Travis’ family and the final showdown in an oil field – are presented on this disc as ‘extra’ features.) A good level of detail is present throughout the film, especially in close-ups, and contrast levels are strong – especially considering how much of the film, which mostly takes place during a single night, was shot in low light conditions. Some shadow detail seems a little ‘crushed’ here and there, perhaps. Midtones are defined and shadows taper off into darkness. Colour reproduction is pleasing and evident from the opening shot, which features a rich blue sky offset by the autumnal greens of a field. The palette is mostly naturalistic, save for a few scenes (vivid red light cast symbolically across the face of Cohen, or a shot of Travis walking across the neon-lit forecourt of a garage/truck stop, for example). Finally, a solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. There’s little to choose between this presentation and Shout! Factory’s US disc: both are equally good, though Arrow’s new disc arguably has a slighty more robust encode. Certainly, those who have only watched the film via one of its VHS releases (the picture not having been released on DVD in the UK) will find this to be a huge upgrade.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is clear and rich throughout, with the shots from Tate’s combat shotgun being particularly bassy and ‘round’. (This disc omits the unnecessary 5.1 upmix included on Shout! Factory’s US disc.) Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and accurate too.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with director Eric Red. This is the same commentary that appeared on the US disc from Shout! Factory. Red discusses his influence – notably the Westerns of John Ford and Sam Peckinpah – and he reflects on the shooting of the film, also considering the MPAA’s insistence that some of the violence be trimmed in order to ensure the film avoided an ‘X’ rating. It’s an informative track, although Red remains silent for a number of scenes. - ‘A Look Back at Cohen & Tate’ (20:43). This featurette also originally appeared on Shout! Factory’s US disc. The featurette is comprised of interviews with Red, cinematographer Victor Kemper, editor Edward Abroms, and actors Kenneth McCabe, Frank Bates and Harley Cross. In terms of Red’s input, there’s some overlap with the commentary track. The participants discuss the origins of the film, its production and the process of putting together the final edit. - Uncut/Extended Scenes: o The Farmhouse (2:11) o Oilfield Shoot-Out (2:48) These are the uncut versions of the two scenes in which violence was trimmed in order for the film to avoid an ‘X’ rating in the US. (The US disc from Shout! Factory included these too, but also contained some expository scenes that were cut from the final edit of the picture – presumably for reasons of pacing.) - Trailer (2:27). - Stills Gallery. The disc also comes with a booklet containing an article by Kim Newman. Newman begins by comparing the road movie with films noir, arguing that in the case of both the label was applied retrospectively. He discusses the popularity of the road movie in the late 1960s and after, and considers some of the earlier films noir which took the form of the road movie – such as Joseph H Lewis’ Gun Crazy (1950). Newman reflects on the theme of movement in Eric Red’s 1980s scripts, and he also talks about the similarities between Cohen & Tate and the aforementioned O Henry story, ‘The Ransom of Red Chief’. The booklet is handsomely illustrated throughout with stills from the film.

Overall

Cohen & Tate is a lurid, comic book-esque movie: dark, self-consciously riddled with film noir tropes (coloured lighting working in conjunction with a chiaroscuro-like visual design), filled with hardboiled dialogue and oh-so-violent moments of action. As in a Garth Ennis comic book (for example, Ennis’ run with Marvel’s The Punisher), the dialogue is all ugly macho posturing, but it’s so well-played by both the ever-dependable Scheider and the sneering Adam Baldwin. In light of Eric Red’s involvement in a rather ugly and well-documented incident in 2000 – in which he drove his car into a bar, killing two people before exiting the vehicle and slashing his own throat with a shard of glass – the climax of this picture, in which Cohen rams through a police blockade before committing a self-annihilating act, seems uncomfortably prescient. Nevertheless, the film’s unapologetic approach to its subject matter carries it through with an unmistakable sense of momentum. This picture is pure, unadulterated, 101-proof pulp of the highest order. Cohen & Tate is a lurid, comic book-esque movie: dark, self-consciously riddled with film noir tropes (coloured lighting working in conjunction with a chiaroscuro-like visual design), filled with hardboiled dialogue and oh-so-violent moments of action. As in a Garth Ennis comic book (for example, Ennis’ run with Marvel’s The Punisher), the dialogue is all ugly macho posturing, but it’s so well-played by both the ever-dependable Scheider and the sneering Adam Baldwin. In light of Eric Red’s involvement in a rather ugly and well-documented incident in 2000 – in which he drove his car into a bar, killing two people before exiting the vehicle and slashing his own throat with a shard of glass – the climax of this picture, in which Cohen rams through a police blockade before committing a self-annihilating act, seems uncomfortably prescient. Nevertheless, the film’s unapologetic approach to its subject matter carries it through with an unmistakable sense of momentum. This picture is pure, unadulterated, 101-proof pulp of the highest order.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray disc is comparable in terms of its presentation to the region ‘A’ release from Shout! Factory in the US; though Shout!’s release contains some more deleted scenes (and an arguably unnecessary 5.1 upmix). This new Blu-ray release from Arrow offers a very welcome HD presentation of a film that has been absent from home video formats in the UK for a good number of years, and offers some strong contextual material. References: Kane, Paul & O’Regan, Marie, 2011: Voices in the Dark: Interviews with Horror Writers, Directors and Actors. London: McFarland & Company Monaco, James, 1992: The Movie Guide. New York: Perigree Books

|

|||||

|