|

|

Guyver AKA The Guyver AKA Mutronics (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th December 2016). |

|

The Film

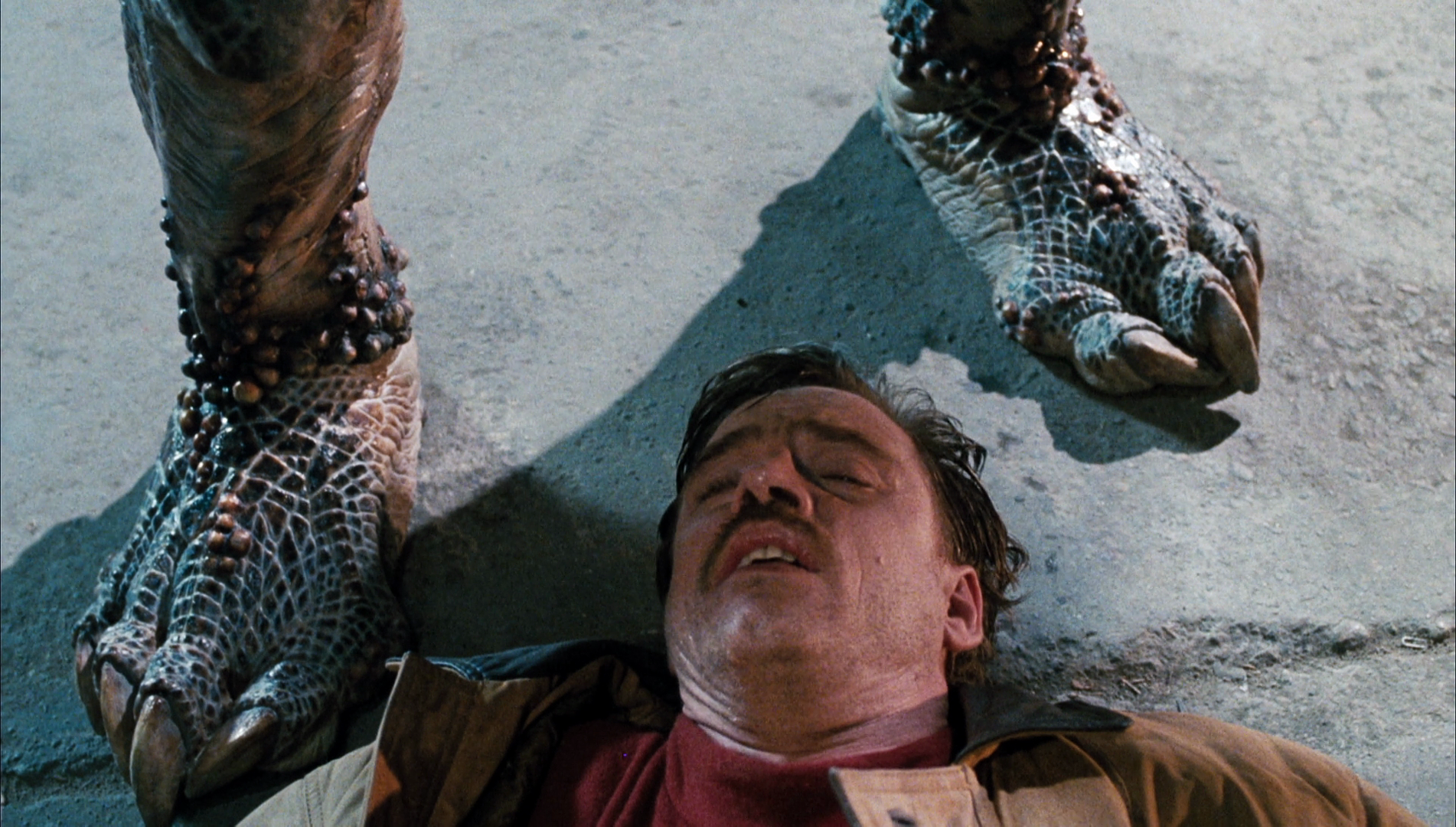

The Guyver AKA The Guyver AKA An employee of the sinister Chronos Corporation, Dr Tetsu Segawa (Greg Paik) is on the run from his employers after discovering the ‘Unit’ – an alien device which, when triggered by a human, will transform into a suit of ‘bio-boosted armour’ and lead to its wearer becoming the Guyver, a cosmic superhero. The Chronos Corporation is desperate to get its hands on this device, sending its agents, Zoanoids (humans capable of transforming into monsters) led by Lisker (Michael Berryman), to kill Segawa and capture the Unit. Lisker and his crew transform into Zoanoids in order to confront Segawa, Lisker killing Segawa in a brutal manner. Unaware that Segawa has secreted the Unit in a lunchbox near the scene, Lisker returns to the head of the Chronos Corporation, Fulton Balcus (David Gale), with the briefcase that Segawa was carrying – only for it to be revealed that the briefcase contains nothing more sinister than a common kitchen toaster. (‘What is this, some sort of masochistic joke?’, Balcus cries out.) Meanwhile, puny Aikido student Sean (Jack Armstrong) has eyes for Dr Segawa’s daughter Mizky (Vivian Wu). When CIA agent Max Reed (Mark Hamill) arrives at Sean’s Aikido dojo to inform Mizky of the death of her father, Sean and Mizky become embroiled inadvertently in the search for the Unit. When Sean stumbles across the Unit in the lunchbox in which Segawa hid it, he is accosted by a street gang. The Unit fuses with Sean’s body, turning him into the Guyver, and he beats off the street gang. Following this, Sean becomes horrified to discover that he can’t remove the armour.  Sean visits Mizky, only to discover that she has been abducted by Lisker and his cronies. Teaming up with Max, who he meets outside, Sean rescues Mizky, but Lisker and his gang pursue Sean, Mizky and Max, eventually trapping them in an abandoned warehouse. In a fight, Lisker discovers the Guyver’s weakness, a silver ball in his forehead. Lisker rips this silver ball from the Guyver, reducing the Guyver to a pile of grue. Lisker returns to Balcus with the silver ball and two captives, Mizky and Max. Sean visits Mizky, only to discover that she has been abducted by Lisker and his cronies. Teaming up with Max, who he meets outside, Sean rescues Mizky, but Lisker and his gang pursue Sean, Mizky and Max, eventually trapping them in an abandoned warehouse. In a fight, Lisker discovers the Guyver’s weakness, a silver ball in his forehead. Lisker rips this silver ball from the Guyver, reducing the Guyver to a pile of grue. Lisker returns to Balcus with the silver ball and two captives, Mizky and Max.

Balcus shows Mizky the experiments deep within the Chronos Corporation: large cylindrical glass tanks in which bizarre creatures are suspended in liquid. The Chronos Corporation is experimenting with transforming people into Zoanoids. Hoping to discover the secret of how to activate the Unit, Balcus threatens to turn Mizky into a Zoanoid. In contact with what remains of the Unit, Mizky manages to activate it, calling Sean/the Guyver back to the world (‘I’ve been rejected by death!’) and triggering a battle with Balcus, who is in fact the Zoalord. Produced by Brian Yuzna with financing from Japan, and directed by special effects maestro Screaming Mad George and Steve Wang, The Guyver (1991) was based on the manga by Takaya Yoshika. Takaya’s manga had already been adapted for the screen, as an anime series. Takaya’s manga told the story of a boy named Sho who discovers a strange alien artefact which, when activated, covers his body in ‘bio booster armour’, effectively rendering him a cyborg and transforming him into the ‘Guyver’. He is pursued by Zoanoids, mutated members of the evil Chronos Corporation, which is set on acquiring the alien artefact. The agents of the Chronos Corporation abduct Sho’s beloved, Mizuki, and Sho is forced to use his newfound fighting skills to rescue her. Like much cyberpunk Japanese fiction of the 1980s and 1990s, such as Tsukamoto Shinya’s Tetsuo (1989) and Tokyo Fist (1995; see our review of that film here), The Guyver is essentially a fantasy of empowerment, telling the story of a mild-mannered male who, through a fusion of his body with technology, becomes what is in essence a ‘superhero’: Susan Napier has suggested that in The Guyver, we are offered ‘a recognizable version of the universal adolescent fantasy of a weakling’s transformation into a superhero. This is a very dark fantasy however. The actual transformation sequences seem agonizing rather than empowering. Even more negatively, Sho’s new powers only serve to bring about the death of his friends and isolate him from humanity permanently’ (Napier, 2005: 92).  Whilst faithful to the narrative of the source manga, this live-action feature film adaptation eschews much of this potential complexity in favour of a knowing, often camp sense of humour, standing in stark contrast to the aforementioned films by Tsukamoto Shinya. Given Screaming Mad George’s work designing the outrageous makeup effects for Yuzna’s superb satire Society (1989; see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of that film here), a first-time viewer of The Guyver might be forgiven for expecting this feature film adaptation of Takaya’s manga to foreground the theme of transformation and offer a dark, nightmarish and surrealistic interpretation of the manga’s themes. However, instead the film (which admittedly features one moderately disturbing transformation scene) focuses on tokusatsu-style martial-arts-and-rubber-suits action, seeming for most of its running time like a feature length episode of the roughly contemporaneous children’s television series Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers (1993-9), a similarly Americanised version of a popular Japanese source text: in the case of Power Rangers, the Japanese source was the popular Super Sentai television franchise (1975-present), footage from which was repurposed by the American producers of Power Rangers. Interviewed about his role in The Guyver, Michael Berryman suggested that the intention in making the picture was to make a movie that was ‘kind of like the old Batman television series in the sixties, very much a pop art, fantasy vein’ (Berryman, quoted in Paul, 2007: 26). The picture was ‘meant to be a humorous fantasy film’ (Berryman, quoted in ibid.: 27). In the same interview, Berryman reveals that much of his dialogue, especially some of the comic back-and-forths that take place in the film between Lisker and his unlikely musclebound lover Weber (played by kickboxer and bodybuilder Spice Williams), was improvised (Berryman, in ibid.). Whilst faithful to the narrative of the source manga, this live-action feature film adaptation eschews much of this potential complexity in favour of a knowing, often camp sense of humour, standing in stark contrast to the aforementioned films by Tsukamoto Shinya. Given Screaming Mad George’s work designing the outrageous makeup effects for Yuzna’s superb satire Society (1989; see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of that film here), a first-time viewer of The Guyver might be forgiven for expecting this feature film adaptation of Takaya’s manga to foreground the theme of transformation and offer a dark, nightmarish and surrealistic interpretation of the manga’s themes. However, instead the film (which admittedly features one moderately disturbing transformation scene) focuses on tokusatsu-style martial-arts-and-rubber-suits action, seeming for most of its running time like a feature length episode of the roughly contemporaneous children’s television series Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers (1993-9), a similarly Americanised version of a popular Japanese source text: in the case of Power Rangers, the Japanese source was the popular Super Sentai television franchise (1975-present), footage from which was repurposed by the American producers of Power Rangers. Interviewed about his role in The Guyver, Michael Berryman suggested that the intention in making the picture was to make a movie that was ‘kind of like the old Batman television series in the sixties, very much a pop art, fantasy vein’ (Berryman, quoted in Paul, 2007: 26). The picture was ‘meant to be a humorous fantasy film’ (Berryman, quoted in ibid.: 27). In the same interview, Berryman reveals that much of his dialogue, especially some of the comic back-and-forths that take place in the film between Lisker and his unlikely musclebound lover Weber (played by kickboxer and bodybuilder Spice Williams), was improvised (Berryman, in ibid.).

The film begins with a fairly lengthy opening titles scrawl which sketches the context for the story that follows. Information comes thick and fast here, which may suggest to the viewer that the film’s narrative is complex; this, of course, isn’t true. However, in its foregrounding of the idea that aliens tampered with the human species in the distant past, the film seems to tap into a similar Chariots of the Gods-type zeitgeist as that which informed The X-Files (Fox, 1993-2001), for example. ‘At the beginning of time, aliens came to the Earth to create the ultimate organic weapon’, this opening titles scrawl says, ‘They created Mankind’. The aliens implanted a ‘special gene’, creating Zoanoids: ‘Humans who can change at will into super monster soldiers’. Meanwhile, the Zoalord has created the Chronos Corporation which is aimed at ‘world domination’, and to achieve this the Zoalord seeks the ‘Unit’ – ‘bio-boosted alien armour’ that will transform a human who wears it into the ‘Guyver’. Later, the film attempts to expand this mythology, Balcus telling Mizky that Zoanoids are ‘warriors developed from the humans by the alien species. In times past they were known as werewolves, minotaurs, vampires. Can you imagine these lovely creatures in the White House; in every seat of power, in every country round the world?’ The film begins with a fairly lengthy opening titles scrawl which sketches the context for the story that follows. Information comes thick and fast here, which may suggest to the viewer that the film’s narrative is complex; this, of course, isn’t true. However, in its foregrounding of the idea that aliens tampered with the human species in the distant past, the film seems to tap into a similar Chariots of the Gods-type zeitgeist as that which informed The X-Files (Fox, 1993-2001), for example. ‘At the beginning of time, aliens came to the Earth to create the ultimate organic weapon’, this opening titles scrawl says, ‘They created Mankind’. The aliens implanted a ‘special gene’, creating Zoanoids: ‘Humans who can change at will into super monster soldiers’. Meanwhile, the Zoalord has created the Chronos Corporation which is aimed at ‘world domination’, and to achieve this the Zoalord seeks the ‘Unit’ – ‘bio-boosted alien armour’ that will transform a human who wears it into the ‘Guyver’. Later, the film attempts to expand this mythology, Balcus telling Mizky that Zoanoids are ‘warriors developed from the humans by the alien species. In times past they were known as werewolves, minotaurs, vampires. Can you imagine these lovely creatures in the White House; in every seat of power, in every country round the world?’

Like many examples of cyberpunk and science fiction from the 1980s and 1990s, from William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and RoboCop (Paul Verhoeven, 1987) to Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991) and Resident Evil (1996), The Guyver features a sinister, evil corporation and its head as the narrative’s chief antagonist. The dialogue foregrounds the shady nature of the Chronos Corporation: ‘This thing must be stopped!’, Segawa asserts when confronted by Lisker, ‘These inhuman experiments must stop!’ Only towards the end of the picture do we see the experiments being conducted by the Chronos Corporation: the transforming of humans into Zoanoids, in large glass tanks.  Moments of camp humour punctuate the story (David Gale telling the bald Berryman that ‘I wouldn’t want a hair on your lovely head hurt’ whilst running his fingers over Berryman’s scalp; the Zoanoid Striker rapping ‘I want that Guyvin’, jivin’ thing’), suggesting that the filmmakers intended to foreground, in a very ‘meta’ way, how ludicrous the finished picture is. When Sean and Max rescue Mizky from Lisker and his gang, they are pursued by Lisker and Striker (Jimmie Walker), who has transformed into his Zoanoid form. Striker clambers over a wall into a film set: a brief glimpse of a lighting technician holding what seems to be a light meter might lead a first-time viewer to believe this to be a ‘goof’ – that the compositions have carelessly revealed the film’s crew to the audience. However, shortly after this moment it is revealed that Striker has inadvertently wandered on to a film set. A woman, an actress in this film-within-the-film (played by genre icon Linnea Quigley, listed simply as ‘Scream Queen’ in the film’s credits), screams at Striker; following this, the film’s director approaches Striker, telling him ‘The suit looks great. You look terrific. But I need you to be more terrifying. You’re a monster. I need you to play this […] with truth’. Moments of camp humour punctuate the story (David Gale telling the bald Berryman that ‘I wouldn’t want a hair on your lovely head hurt’ whilst running his fingers over Berryman’s scalp; the Zoanoid Striker rapping ‘I want that Guyvin’, jivin’ thing’), suggesting that the filmmakers intended to foreground, in a very ‘meta’ way, how ludicrous the finished picture is. When Sean and Max rescue Mizky from Lisker and his gang, they are pursued by Lisker and Striker (Jimmie Walker), who has transformed into his Zoanoid form. Striker clambers over a wall into a film set: a brief glimpse of a lighting technician holding what seems to be a light meter might lead a first-time viewer to believe this to be a ‘goof’ – that the compositions have carelessly revealed the film’s crew to the audience. However, shortly after this moment it is revealed that Striker has inadvertently wandered on to a film set. A woman, an actress in this film-within-the-film (played by genre icon Linnea Quigley, listed simply as ‘Scream Queen’ in the film’s credits), screams at Striker; following this, the film’s director approaches Striker, telling him ‘The suit looks great. You look terrific. But I need you to be more terrifying. You’re a monster. I need you to play this […] with truth’.

The metafictional aspect of the film is heightened by references to other pictures. For example, Jeffrey Combs appears as Dr East, an employee of the Chronos Corporation, his name a clear allusion to his role as Dr Herbert West in Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator (1985), which Yuzna also produced and which starred David Gale as a corrupt authority figure. ‘So you’re still chasing Ninja Turtles, huh?’, one of Max’s colleagues asks him, and this film has a similar mixture of rubber suits and martial arts to the live action Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film that had been released a year earlier (in 1990). When Lisker reveals that he has flubbed the mission to secure the Unit, returning instead a toaster to the Chronos Corporation, Fulton Balcus uses a form of telepathy to have Lisker beat himself (‘I’ll have you slap yourself into oblivion if you don’t find it [the Unit]’, Balcus declares). This scene, with Berryman’s character attacking himself, has a slapstick Three Stooges-esque quality that makes it similar to the scenes in Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead II: Dead By Dawn (1987) in which the evil invades Ash’s (Bruce Campbell) hand, causing it to attack its owner. Balcus use of telepathic communication to facilitate this moment might also remind the viewer of the scenes exclusive to the television cut of Re-Animator, in which David Gale’s Dr Hill, uses telepathy to force others to do his bidding. Balcus also leers over the captive Mizky in a similar manner to which Hill leers over Megan in Re-Animator (‘I’ve always admired your beauty, my dear’): ‘You could easily become one of them [the Zoanoids]’, Balcus tells Mizky, ‘A rare specimen indeed. With beauty like yours, you might not become so hideous’.

Video

This presentation contains the ‘director’s cut’ of the film, running 92:26 mins. When distributed in America, the film’s running time was abbreviated, the distributors cutting out many of the comic scenes. According to Yuzna, the version of the film released in Japan was the preferred cut of Screaming Mad George and Steve Wang (Yuzna, cited in Fischer, 2000: 662). Yuzna said in interview that ‘they [the distributors in the US] cut it to make it a more commercial movie. It’s shorter and they cut it to get to the action more, it doesn’t spend as much time with the characters’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). The distributor also removed some of the film’s comic book-style edits – what Yuzna called ‘these cartoony slash cuts and stuff’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). The ‘director’s cut’ surfaced on DVD in the early 2000s, though in the meantime another variant edit had appeared on VHS cassette, missing the narrative footage like the US theatrical cut but adding some brief moments of gore to three of the action scenes. The original Japanese release apparently contained all of the narrative footage cut from every other version of the film and the additional gore footage; this cut of the film was released on LaserDisc in Japan, in English with Japanese subtitles. (This LaserDisc release, I believe, is the only time that the 'director's cut' with the three scenes of gore included in it has been released to home video.) The ‘director’s cut’, as presented here, omits these moments of gore but restores the comic book-style edits and the narrative footage cut from the version of the film originally released in the US and UK. This presentation contains the ‘director’s cut’ of the film, running 92:26 mins. When distributed in America, the film’s running time was abbreviated, the distributors cutting out many of the comic scenes. According to Yuzna, the version of the film released in Japan was the preferred cut of Screaming Mad George and Steve Wang (Yuzna, cited in Fischer, 2000: 662). Yuzna said in interview that ‘they [the distributors in the US] cut it to make it a more commercial movie. It’s shorter and they cut it to get to the action more, it doesn’t spend as much time with the characters’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). The distributor also removed some of the film’s comic book-style edits – what Yuzna called ‘these cartoony slash cuts and stuff’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). The ‘director’s cut’ surfaced on DVD in the early 2000s, though in the meantime another variant edit had appeared on VHS cassette, missing the narrative footage like the US theatrical cut but adding some brief moments of gore to three of the action scenes. The original Japanese release apparently contained all of the narrative footage cut from every other version of the film and the additional gore footage; this cut of the film was released on LaserDisc in Japan, in English with Japanese subtitles. (This LaserDisc release, I believe, is the only time that the 'director's cut' with the three scenes of gore included in it has been released to home video.) The ‘director’s cut’, as presented here, omits these moments of gore but restores the comic book-style edits and the narrative footage cut from the version of the film originally released in the US and UK.

Presented in 1.78:1, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. I’m not entirely sure of the source for this presentation (it seems to have been sourced from Germany and most certainly uses the same master as the Blu-ray releases of the film available in Germany), but it’s either taken from a print removed several generations from the negative or has suffered some contrast boosting somewhere along the way. Shadow detail is often ‘crushed’ and highlights are equally flat in places. (See some of the large screen grabs at the bottom of this review for illustration of this.) Colour reproduction is good, but reds sometimes seem a little elevated. The level of detail within the presentation is a cut above that available in the film’s DVD releases, but on the whole the presentation looks quite ‘flat’: even shots that should have strong depth of field seem relatively depthless. It’s a flatness that seems above and beyond what one might expect from a low budget 1990s production, even. The structure of 35mm film seems to be retained, however. Any weaknesses seem to be within the master provided to Arrow, rather than Arrow’s handling of it. It’s probably the best presentation available currently but there’s certainly room for improvement.

Audio

Two audio options are present, both in English: a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, and a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. Both of these are as clear as they need to be, but the 5.1 track feels more ‘rounded’ and features some good sound separation effects. (On the other hand, purists may want to stick to the stereo track.) Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided; these are easy to read and error-free.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An interview with Brian Yuzna (8:50). Interviewed by Mark Alan Miller, Yuzna discusses the origins of the project and how he came to produce the film. He talks about how Screaming Mad George and Steve Wang collaborated on the film, and he reflects on the differences between the mangas and the animes. Believing that ‘there would be too many cooks’, Yuzna opted not to have input into the screenplay – which is unusual for a film produced by Yuzna. Yuzna also comments on the casting of the film and how some of the European artwork sold the film on the suggestion that Mark Hamill was the titular Guyver. Some of the effects work is discussed in detail too. Yuzna makes some interesting comments about the editing of the film, commenting on the omission of scenes in the US version, and also makes some observations about the titling of the film (the confusion over whether the film is ‘Guyver’ or ‘The Guyver’, and the retitling of the picture as ‘Mutronics’ for its European releases). - The film’s US trailer (0:25). - The film’s international trailer (2:33). - Several galleries: a behind-the-scenes gallery (2:55); a figurine gallery (1:06); and an artwork gallery (3:55). These are what you would expect them to be from their titles. The ‘figurine gallery’ offers a series of images of figurines of the Guyver and a couple of the Zoanoids. The ‘artwork gallery’ contains shots of the film’s VHS and DVD artwork from around the world. A booklet is included in initial pressings of the release. We were unable to source a copy of the booklet at the time that this review went ‘live’, but if we manage to acquire one in the near future we will update this section of the review to comment on it.

Overall

The Guyver is a strange multi-cultural hodgepodge that doesn’t quite work as well as it should but nevertheless has a strong following. When Max Reed visits Mizky at the Aikido dojo to inform her of the death of her father, he tells her that he witnessed Dr Segawa’s murder and ‘I couldn’t quite make out what was going on. It was violent; weird’. The viewer might be left with a similar impression of The Guyver. A fan of the picture might be able to argue that it is a masterpiece of the absurd, the bizarre and the fantastical, but it doesn’t quite reach the heights (or depths, depending on your point of view) of, for example, Simon Nam’s similarly bizarre monsters-and-martial arts picture Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky (1991), itself a live-action adaptation of a manga source and released the same year as The Guyver. The Guyver is a strange multi-cultural hodgepodge that doesn’t quite work as well as it should but nevertheless has a strong following. When Max Reed visits Mizky at the Aikido dojo to inform her of the death of her father, he tells her that he witnessed Dr Segawa’s murder and ‘I couldn’t quite make out what was going on. It was violent; weird’. The viewer might be left with a similar impression of The Guyver. A fan of the picture might be able to argue that it is a masterpiece of the absurd, the bizarre and the fantastical, but it doesn’t quite reach the heights (or depths, depending on your point of view) of, for example, Simon Nam’s similarly bizarre monsters-and-martial arts picture Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky (1991), itself a live-action adaptation of a manga source and released the same year as The Guyver.

Arrow’s disc includes a serviceable presentation of the ‘director’s cut’ of the film. It’s certainly a cut above the film’s DVD releases, and seems for all intents and purposes to be taken from the same source as the German Blu-ray releases of the same title (though with the added benefit of lossless sound: the German BDs featured only Dolby Digital audio tracks), but there’s room for improvement: Arrow seem to have done their best with the provided materials, but whatever master used here seems to be lacking in the dynamic range of 35mm film and has a curious flatness to it. In terms of its various edits, The Guyver seems to have almost as complicated a history as, for example, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982); in light of this, it’s a shame that Arrow haven’t sourced the violent content from the film’s VHS releases, as this material could even have been included as an ‘extra’ feature, but nevertheless the violence in that cut of the film is fleeting and doesn’t add an awful lot to the narrative. Fans of the film who don’t own the German Blu-ray releases will find this to be a worthwhile upgrade over their DVD copies of the film’s ‘director’s cut’; completists will want to hang onto whatever releases of the film they have which contain the three added moments of grue. References: Fischer, Dennis, 2000: Science Fiction Film Directors, 1895-1998. London: McFarland and Company, Inc. Napier, Susan J, 2005: Anime from “Akira” to “Howl’s Moving Castle”: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. St Martin’s Griffin Paul, Louis, 2007: Tales from the Cult Film Trenches: Interviews with 36 Actors from Horror, Science Fiction and Exploitation Cinema. London: McFarland & Company, inc

|

|||||

|