|

|

Rawhide AKA Desperate Siege (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (12th March 2017). |

|

The Film

Rawhide (Henry Hathaway, 1951) Rawhide (Henry Hathaway, 1951)

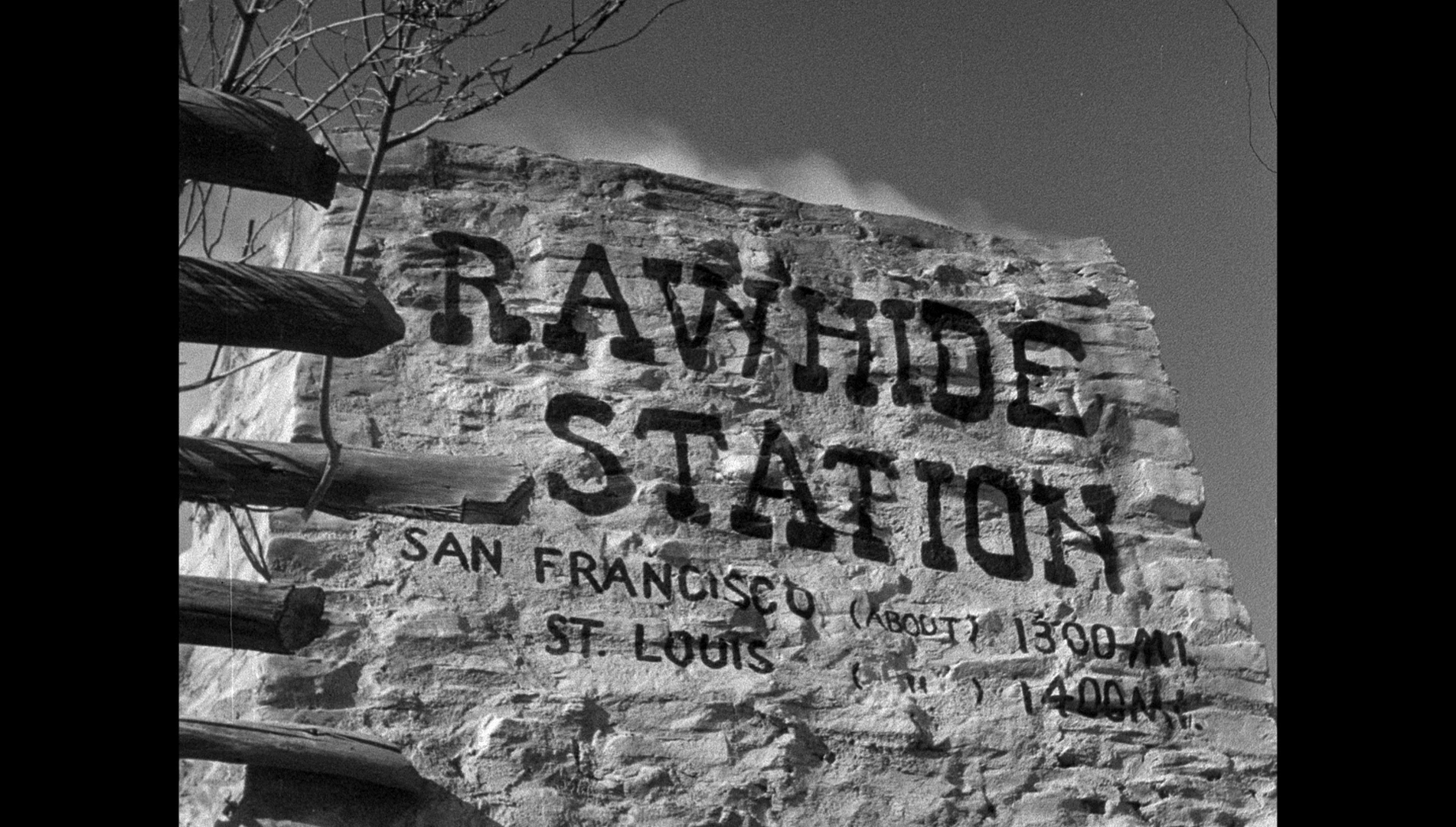

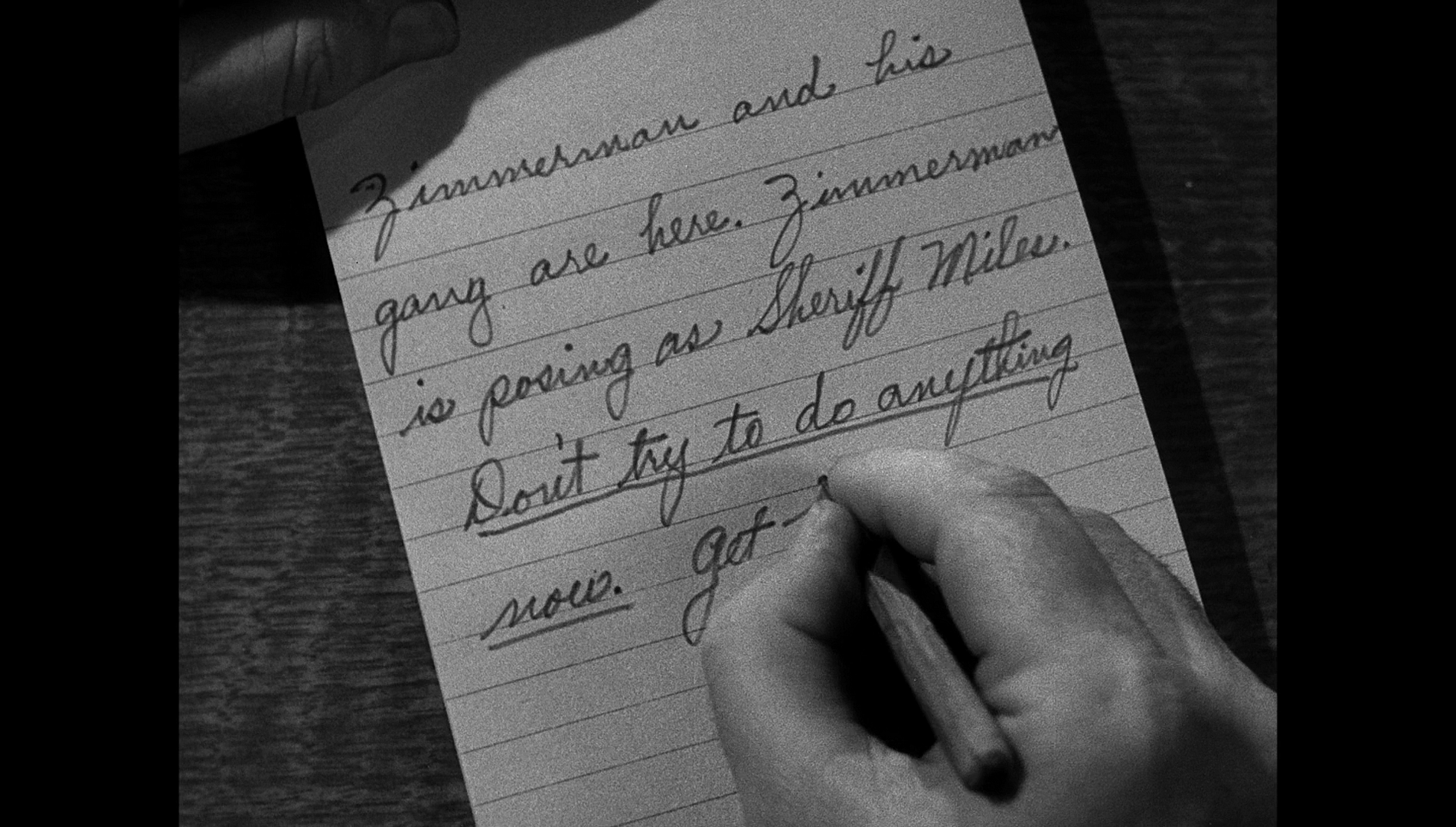

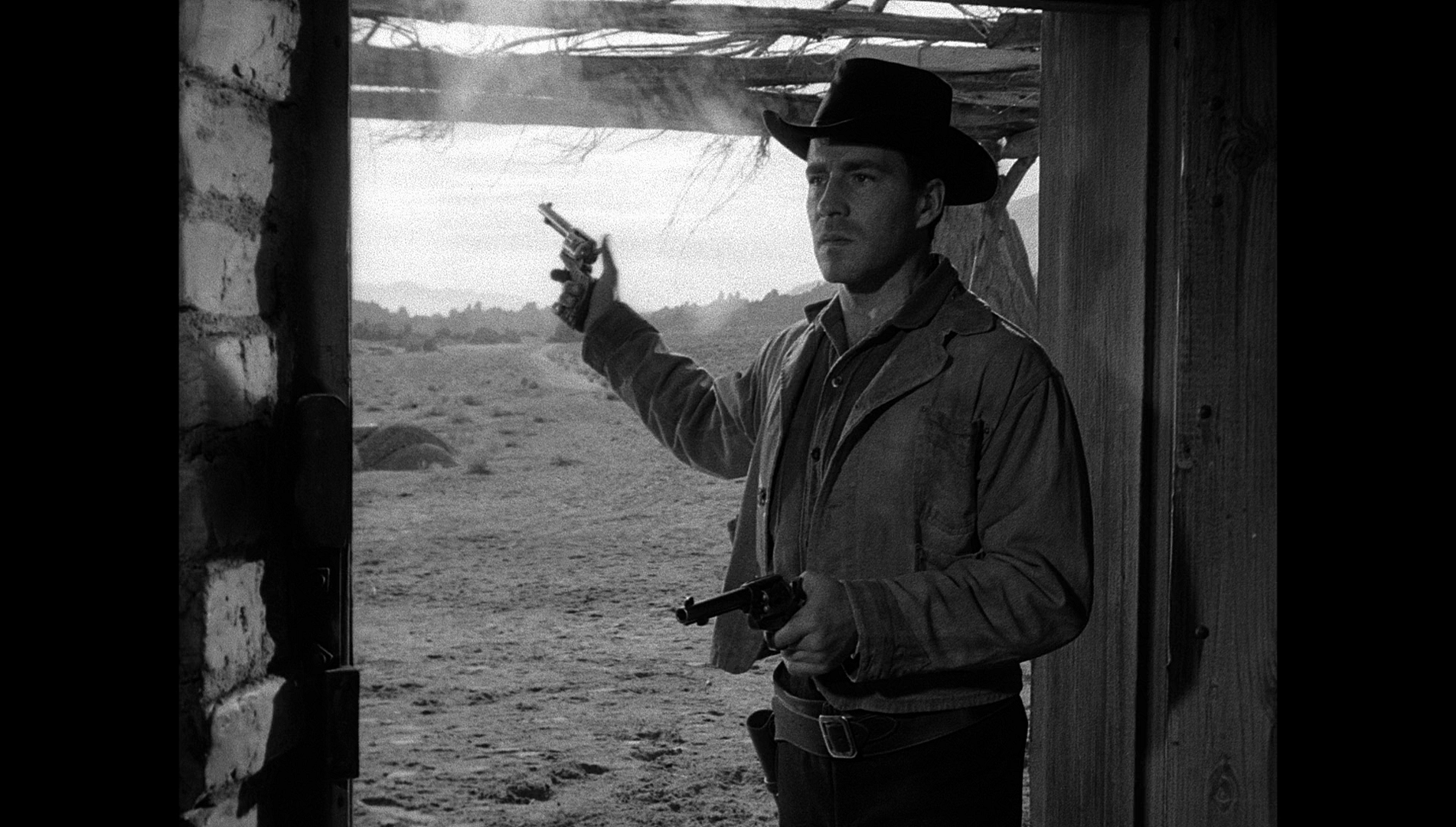

Son of J C Owens, the superintendent of the eastern division of the Overland Mail, Tom Owens (Tyrone Power) is a dandy; seemingly an embarrassment to his father, Tom has been given the role of underling at the isolated Rawhide Pass relay station, on the San Francisco to St Louis line. Tom works as the assistant of the ageing stationmaster, Sam Todd (Edgar Buchanan). Tom plans to ‘go back east’ within the next week. A stagecoach arrives; on the stagecoach is a woman, Vinnie Holt (Susan Hayward), who is accompanied by a young child, Callie (Judy Ann Dunn). However, a cavalry patrol approach the station and inform those there that a murderer named Zimmermann has escaped and, with a group of men, has killed a number of people including one of Sam’s friends, Johnny Madden. Owing to one of the stagecoach company’s policies, not to risk the lives of children, Vinnie and Callie are left behind at the Rawhide Pass station, whilst the stagecoach is escorted to its destination by the cavalry patrol. The station is approached by a man identifying himself as Deputy Sheriff Miles from Huntsville. However, ‘Miles’ soon reveals himself to be Zimmermann (Hugh Marlowe), the outlaw. Zimmermann and his gang – Yancy (Dean Jagger), Gratz (George Tobias) and the leering, sadistic Tevis (Jack Elam) – overpower old Sam and beat him. Following this, the outlaws reveal that they are there with the intention of robbing a stagecoach which is carrying a load of gold bullion. When Sam tries to run away, he is shot in the back and killed by Tevis. The gang believe Vinnie to be Tom’s wife, and Tom tells Vinnie to play along with this illusion because the gang need him – and by masquerading as Tom’s wife, Vinnie may ensure that she and Callie survive at least until the stagecoach carrying the bullion pulls in to the station. When Tom and Vinnie are locked in a room in the stagecoach station, Tom manages to conceal a breadknife in a water pitcher, and the pair set out to use the knife to dig an escape tunnel through the external wall of the station.  The picture begins and ends with a breathless, friendly voiceover (by an uncredited Gary Merrill), in a similar vein to Carol Reed’s opening narration for The Third Man (Reed, 1948), which establishes the film’s focus on the Rawhide Pass relay station, the location in which all of the story’s action takes place: ‘Yes, sir; that’s it’, the narrator intones, ‘The Overland Mail. San Francisco to St Louis in twenty-five days. 2700 miles in twenty-five days and twenty-five nights, when the weather and Indians behave. People said it couldn’t be done. They laughed, called it the “Jackass Mail”’. The picture begins and ends with a breathless, friendly voiceover (by an uncredited Gary Merrill), in a similar vein to Carol Reed’s opening narration for The Third Man (Reed, 1948), which establishes the film’s focus on the Rawhide Pass relay station, the location in which all of the story’s action takes place: ‘Yes, sir; that’s it’, the narrator intones, ‘The Overland Mail. San Francisco to St Louis in twenty-five days. 2700 miles in twenty-five days and twenty-five nights, when the weather and Indians behave. People said it couldn’t be done. They laughed, called it the “Jackass Mail”’.

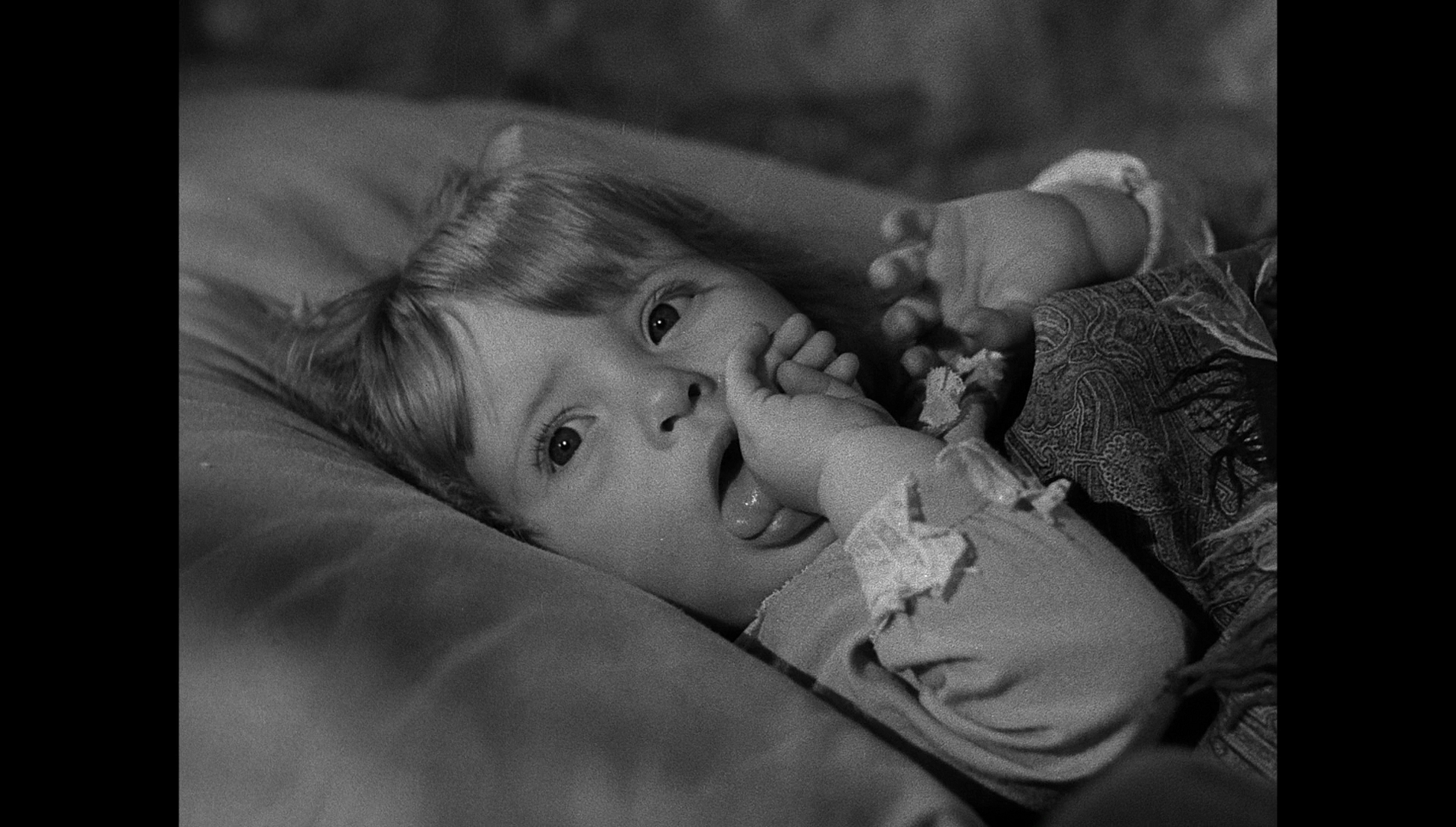

Rawhide features some stellar location work, with strong use of locations at Lone Pine, California – the location of choice for many Western films from the silent era onwards, including those of director Budd Boetticher, whose Ranown productions (such as Ride Lonesome, 1959) were shot there. Rawhide’s focus on a small cast who are tethered to a specific location is familiar paradigm from a number of ‘adult’ Westerns of the 1940s and 1950s, including pictures such as Yellow Sky (William A Wellman, 1948), Andre de Toth’s Day of the Outlaw (1958) and Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). As with many of these ‘adult’ Westerns, especially Day of the Outlaw and other similar films including Raoul Walsh’s Pursued (1948) and Robert Wise’s Blood on the Moon (1948), Rawhide is arguably as much a film noir as it is a Western, its strong female lead and its moral complexities (Zimmerman is revealed to be a once urbane man who slipped into a life of crime, and whose control over his gang is revealed to be illusory) amplified by the film’s use of monochrome photography. Quentin Tarantino’s recent The Hateful Eight (2016) seems to look as much towards these films for its inspiration as to the westerns all’italiana that so obviously influenced the Tarantino picture’s visual design - though at least one western all’italiana, Giuseppe Vari’s Prega il morto e ammazza il vivo/Shoot the Living, Pray for the Dead (1971), featured a similar narrative paradigm, the bulk of its story taking place in a stagecoach station. Like Rawhide, The Tall T and Prega il morto e ammazza il vivo, for example, the narrative of The Hateful Eight focuses almost exclusively on a stagecoach station where a group of individuals are held hostage by outlaws.  Rawhide’s representation of its lead female character marks it as a distinctly post-war picture. When Vinnie is introduced disembarking from her stagecoach at the Rawhide Pass station, she is accompanied by Callie and Sam rolls his eyes disapprovingly when Vinnie insists she is ‘Miss Holt after he mistakenly addresses her as ‘Mrs Holt’. Of course, at this stage in the narrative, both the audience and the characters in the film assume that Callie is Vinnie’s daughter – though later in the picture, it’s revealed Callie is Vinnie’s niece and that Vinnie’s adoption of Callie is a profoundly selfless act, committed out of Vinnie’s love for her niece and now deceased sister. After Sam has been killed by the gang, Vinnie explains her relationship with Callie to Tom, telling him that Callie is Vinnie’s sister Jeanie’s child, and that Jeanie and her husband Johnny were killed after moving to California – ‘from mining camp to mining camp’ – in search of a gold claim. Johnny was a jealous man and his jealousy led to himself and Jeanie being shot by a man he accused of being Jeanie’s suitor. Following their deaths, Vinnie assumed guardianship of Callie. With this revelation, the film’s representation of Vinnie shifts from the paradigm encapsulated within Sam’s quietly judgemental response to Vinnie’s assertion that she be called ‘Miss Holt’, to the realisation that Vinnie is a strong, independently-minded and morally righteous woman. The film goes on to show the extent to which Vinnie lives in a society in which women are viewed as helpless and vulnerable, an attitude which Vinnie strives to correct as the narrative progresses. Vinnie and Callie are left behind at the station by the cavalry, who insist (ironically, given the later developments in the narrative) that this is to protect the pair against the possibility of the stagecoach being attacked by Zimmermann’s gang: ‘It’s a company rule not to risk the lives of children’, Sam tells Vinnie. She protests angrily when Tom carries her away from the stagecoach: ‘Let me go, you fool: you’ll make me lose my job’, she shouts, highlighting her status as an independent woman – something presumably intended to chime with post-war audiences. Rawhide’s representation of its lead female character marks it as a distinctly post-war picture. When Vinnie is introduced disembarking from her stagecoach at the Rawhide Pass station, she is accompanied by Callie and Sam rolls his eyes disapprovingly when Vinnie insists she is ‘Miss Holt after he mistakenly addresses her as ‘Mrs Holt’. Of course, at this stage in the narrative, both the audience and the characters in the film assume that Callie is Vinnie’s daughter – though later in the picture, it’s revealed Callie is Vinnie’s niece and that Vinnie’s adoption of Callie is a profoundly selfless act, committed out of Vinnie’s love for her niece and now deceased sister. After Sam has been killed by the gang, Vinnie explains her relationship with Callie to Tom, telling him that Callie is Vinnie’s sister Jeanie’s child, and that Jeanie and her husband Johnny were killed after moving to California – ‘from mining camp to mining camp’ – in search of a gold claim. Johnny was a jealous man and his jealousy led to himself and Jeanie being shot by a man he accused of being Jeanie’s suitor. Following their deaths, Vinnie assumed guardianship of Callie. With this revelation, the film’s representation of Vinnie shifts from the paradigm encapsulated within Sam’s quietly judgemental response to Vinnie’s assertion that she be called ‘Miss Holt’, to the realisation that Vinnie is a strong, independently-minded and morally righteous woman. The film goes on to show the extent to which Vinnie lives in a society in which women are viewed as helpless and vulnerable, an attitude which Vinnie strives to correct as the narrative progresses. Vinnie and Callie are left behind at the station by the cavalry, who insist (ironically, given the later developments in the narrative) that this is to protect the pair against the possibility of the stagecoach being attacked by Zimmermann’s gang: ‘It’s a company rule not to risk the lives of children’, Sam tells Vinnie. She protests angrily when Tom carries her away from the stagecoach: ‘Let me go, you fool: you’ll make me lose my job’, she shouts, highlighting her status as an independent woman – something presumably intended to chime with post-war audiences.

Curiously, however, much of the literature written about Rawhide mentions somewhere or other Susan Hayward’s underwear, or lack of it: in a publicity piece that circulated in a number of newspapers during production of the film in 1950, readers were told that Hayward ‘nixed long woolen underwear’ for the scenes shot on location at Lone Pine, arguing ‘I’d rather look good than be warm’, but soon relented after a single day of a temperature hovering around twelve degrees, telling the film’s assistant director (Abe Steinberg) ‘Break out the long underwear, I’m ready’ (Johnson, 1950a: 14; Johnson, 1950b: 4). Charles Martin Morfin’s book Location Filming in the Alabama Hills also includes amongst its list of anecdotes about the production (‘Twin children were used during filming; one would cry for some scenes as needed, and the other would not cry. Power often pretended to be a local in town, posing as a hotel clerk as a practical joke to see if he would be noticed’) the observation that ‘Hayward was rumored not to wear undergarments while relaxing in town’ (Morfin, 2014: 91). What this says about the film, I’m not sure – but it highlights how films of the 1950s were promoted with the insinuation of sex and sexuality, and Hayward is framed within some mildly fetishistic imagery in the completed film – laid out under a table, her head obscured but her buttocks and bare legs exposed, one high heeled shoe on and the other off to expose the sole of her bare foot (Hayward’s character is, during this moment, using the other high heeled shoe rather impractically as a mallet to hammer the knife into the adobe walls of the stagecoach station). This is imagery that would make Quentin Tarantino proud – tame by modern standards, perhaps, but in a coded way (that is reinforced by a cut to a close-up of Power as he walks into the room and sees this sight) as suggestive to 1950s audiences as Tina Louise’s heaving bosoms in Andre de Toth’s later ‘adult Western’ Day of the Outlaw (1958). Also, despite the film’s framing of Vinnie as an independent, capable woman, she is reduced to the conventional damsel in distress when Tevis threatens her with sexual assault whilst they hide out in a rock formation near the station. Curiously, however, much of the literature written about Rawhide mentions somewhere or other Susan Hayward’s underwear, or lack of it: in a publicity piece that circulated in a number of newspapers during production of the film in 1950, readers were told that Hayward ‘nixed long woolen underwear’ for the scenes shot on location at Lone Pine, arguing ‘I’d rather look good than be warm’, but soon relented after a single day of a temperature hovering around twelve degrees, telling the film’s assistant director (Abe Steinberg) ‘Break out the long underwear, I’m ready’ (Johnson, 1950a: 14; Johnson, 1950b: 4). Charles Martin Morfin’s book Location Filming in the Alabama Hills also includes amongst its list of anecdotes about the production (‘Twin children were used during filming; one would cry for some scenes as needed, and the other would not cry. Power often pretended to be a local in town, posing as a hotel clerk as a practical joke to see if he would be noticed’) the observation that ‘Hayward was rumored not to wear undergarments while relaxing in town’ (Morfin, 2014: 91). What this says about the film, I’m not sure – but it highlights how films of the 1950s were promoted with the insinuation of sex and sexuality, and Hayward is framed within some mildly fetishistic imagery in the completed film – laid out under a table, her head obscured but her buttocks and bare legs exposed, one high heeled shoe on and the other off to expose the sole of her bare foot (Hayward’s character is, during this moment, using the other high heeled shoe rather impractically as a mallet to hammer the knife into the adobe walls of the stagecoach station). This is imagery that would make Quentin Tarantino proud – tame by modern standards, perhaps, but in a coded way (that is reinforced by a cut to a close-up of Power as he walks into the room and sees this sight) as suggestive to 1950s audiences as Tina Louise’s heaving bosoms in Andre de Toth’s later ‘adult Western’ Day of the Outlaw (1958). Also, despite the film’s framing of Vinnie as an independent, capable woman, she is reduced to the conventional damsel in distress when Tevis threatens her with sexual assault whilst they hide out in a rock formation near the station.

Tyrone Power was just coming over the peak of his stardom when Rawhide was released: alongside Gregory Peck, he was Fox’s top male actor of the day but would soon be supplanted. Tall, dark and handsome, Power fared equally well in the swashbucklers with which he was most closely associated, films noir such as The Razor’s Edge (Edmund Goulding, 1946) and westerns like Rawhide. Power’s character, Tom Owen, is introduced preening himself in a mirror. He is a dandy, a ‘dude’, whose status as such is signified in a pair of fancy shoes with spats that Yanky takes a fancy to and steals for himself. Tom’s father, J C Owens, is a ‘hard man’, the superintendent of the eastern division of the Overland Mail, who has a reputation for violence; Tom is an embarrassment and has been sent to the Rawhide station to keep him out of the way. At the start of the film, Sam berates Tom for being ‘as much of a dude as when he [Tom’s father] sent you out here’. Tom’s experience with Zimmermann’s gang is, as Tom says at the end of the film, an example of ‘learning the trade’.  Though not necessarily as complex as Glenn Ford’s outlaw, Ben Wade, in Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma (1957), Zimmermann is far from a cardboard cutout villain. Like Ben Wade in 3:10 to Yuma, Zimmermann is articulate and charming. Zimmermann is an educated man, a former banker incarcerated following his murder of his lover after he caught her in flagrante delicto with another man. (Zimmermann’s ‘backstory’ has dry echoes of the narrative of Johnny and Jeanie that Vinnie tells to Tom, though with a very different conclusion.) Zimmermann has escaped from the prison in which he was held, and his gang isn’t one of his own selection but rather one of convenience – these are simply the men with whom Zimmermann escaped. ‘Now let’s get this straight’, Zimmermann tells his gang at one point in the film, ‘I didn’t pick any of you for this. You just happened to be there when I made my break; that’s my bad luck’. The alliances within the gang – especially between the more gentlemanly Zimmermann and the sadistic Tevis, who represents a sexual threat to Vinnie – are fragile. When Tevis threatens Vinnie with sexual assault, Zimmermann steps in to stop him; but Tevis harbours barely concealed resentment towards Zimmermann. ‘I’ll kill you for this’, Tevis promises Zimmermann after the latter has struck Tevis following one of Tevis’ attempted assaults upon Vinnie. Towards the end of the film, Tom makes an appeal to Zimmermann regarding Zimmermann’s use of Tevis to ‘guard’ Vinnie and Callie: ‘What kind of man are you, Zimmermann?’, Tom asks, ‘Anyone can see you are educated and have a good background. I could understand the thinking of a road agent [… but] how a man like you could leave a woman and child alone with an animal like that [Tevis], I can’t understand’. ‘When you get old and some of the green wears off of you, you’ll learn not to trust anyone or anything’, Zimmermann responds bitterly. Though not necessarily as complex as Glenn Ford’s outlaw, Ben Wade, in Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma (1957), Zimmermann is far from a cardboard cutout villain. Like Ben Wade in 3:10 to Yuma, Zimmermann is articulate and charming. Zimmermann is an educated man, a former banker incarcerated following his murder of his lover after he caught her in flagrante delicto with another man. (Zimmermann’s ‘backstory’ has dry echoes of the narrative of Johnny and Jeanie that Vinnie tells to Tom, though with a very different conclusion.) Zimmermann has escaped from the prison in which he was held, and his gang isn’t one of his own selection but rather one of convenience – these are simply the men with whom Zimmermann escaped. ‘Now let’s get this straight’, Zimmermann tells his gang at one point in the film, ‘I didn’t pick any of you for this. You just happened to be there when I made my break; that’s my bad luck’. The alliances within the gang – especially between the more gentlemanly Zimmermann and the sadistic Tevis, who represents a sexual threat to Vinnie – are fragile. When Tevis threatens Vinnie with sexual assault, Zimmermann steps in to stop him; but Tevis harbours barely concealed resentment towards Zimmermann. ‘I’ll kill you for this’, Tevis promises Zimmermann after the latter has struck Tevis following one of Tevis’ attempted assaults upon Vinnie. Towards the end of the film, Tom makes an appeal to Zimmermann regarding Zimmermann’s use of Tevis to ‘guard’ Vinnie and Callie: ‘What kind of man are you, Zimmermann?’, Tom asks, ‘Anyone can see you are educated and have a good background. I could understand the thinking of a road agent [… but] how a man like you could leave a woman and child alone with an animal like that [Tevis], I can’t understand’. ‘When you get old and some of the green wears off of you, you’ll learn not to trust anyone or anything’, Zimmermann responds bitterly.

As with many adult Westerns of the 1950s, Rawhide features some cruel, savage violence, most of it administered by Tevis in a blazingly animalistic performance from Jack Elam. The beating administered by Zimmermann’s gang upon the defenceless Sam, followed shortly after by Sam being shot in the back whilst trying to escape, is particularly cruel to watch; after Sam has been shot in the back, Tevis cements his role in the film as the sadistic ‘dog heavy’ by executing Sam in cold blood. ‘He won’t hand us no more lies’, Tevis says when he has done this, ‘You want me to take care of him [Tom] too?’ A little later, Tevis is shown dragging Sam’s corpse via a rope tied to his horse. ‘That’s a rotten thing to do’, Tom says, watching from the doorway of the station. Zimmermann responds by asserting that Tevis ‘has no respect for the dead’. ‘And he just loves the living’, Vinnie asserts sarcastically. As with many adult Westerns of the 1950s, Rawhide features some cruel, savage violence, most of it administered by Tevis in a blazingly animalistic performance from Jack Elam. The beating administered by Zimmermann’s gang upon the defenceless Sam, followed shortly after by Sam being shot in the back whilst trying to escape, is particularly cruel to watch; after Sam has been shot in the back, Tevis cements his role in the film as the sadistic ‘dog heavy’ by executing Sam in cold blood. ‘He won’t hand us no more lies’, Tevis says when he has done this, ‘You want me to take care of him [Tom] too?’ A little later, Tevis is shown dragging Sam’s corpse via a rope tied to his horse. ‘That’s a rotten thing to do’, Tom says, watching from the doorway of the station. Zimmermann responds by asserting that Tevis ‘has no respect for the dead’. ‘And he just loves the living’, Vinnie asserts sarcastically.

In particular, throughout the film Tevis represents a strong threat of sexual assault directed towards Vinnie. He leers at her and, whenever the suggestion is made that Tevis and Vinnie be left alone, he approaches her with bold desire in his eyes. ‘I ain’t been cured of women yet’, Tevis asserts seedily whilst gazing at Vinnie: ‘Ain’t had your medicine, Zim’, he adds in reference to Zimmermann’s killing of his own wife following the revelation that she was involved in an extramarital affair with another man, an experience that has led to a profound distrust of women within Zimmermann. When a stagecoach arrives at the station the next morning, Zimmermann has Tevis take Vinnie out to a nearby rock formation, and Vinnie is framed with Tevis approaching her in the background, his intention of raping Vinnie writ across his face. ‘You know how long it’s been since I saw a pretty face, girlie?’, he hisses at her. The film’s climactic shootout takes place between Tevis and Tom; the pair reach a stalemate which is broken when Callie, who has wandered away from Vinnie, approaches innocently. Tevis makes the decision to shoot at the ground around Callie, causing the young child to scream in fear. (The seemingly genuine sense of fear on the child actor’s face, as the small explosive devices set on the floor around her to simulate the bullets hitting dirt are set off, is difficult to watch; as noted above, the production reputedly used two child actors, one of which who wouldn’t cry and another who would cry on cue.)  Interestingly, and against the conventions established in many Hollywood films, Rawhide depicts in painstaking detail the effort Tom and Vinnie go to in an attempt to dig a hole through the wall of room in the stagecoach station in which they have been trapped by Zimmermann, only for this escape route never to be used by the pair. The use of the knife to dig through the wall is shown in shots that approximate the ‘cinema of process’ that has been seen in, for example, the incredible detail with which the heist is shown in Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955). Colin McArthur originated the term ‘cinema of process’ in reference to Jean-Pierre Melville’s crime films of the late 1960s and early 1970s (for example, Le cercle rouge, 1970), describing Melville’s ‘cinema of process’ as ‘a cinema which went some way to honouring the integrity of actions by allowing them to happen in a way significantly closer to “real” time than was formerly the case in fictive, particularly Hollywood, cinema’ (McArthur, 2000: 191). MacArthur suggests that the ‘cinema of process’ grew out of Dassin’s depiction of the heist in Rififi. However, Rawhide’s depiction of Vinnie and Tom’s attempt to dig through the wall feels like an earlier example of this method, the scenes feeling almost as if they are shot in ‘real time’ as Hathaway cuts from either Tom or Vinnie under the table as they attempt to use the knife to chip away at the wall, to the other of the pair standing guard near the door and listening for Zimmermann or Tevis. The digging of this hole is shown with the same amount of detail as an audience might associated with jailbreak stories: for example, the digging of the holes intended to be used as escape routs in Jacques Becker’s Le trou (1960), The Great Escape (John Sturges, 1963) or Escape from Alcatraz (Don Siegel, 1979). However, unlike in those films, the escape route is never used for its intended purpose. It’s an interesting subversion of the paradigms of Hollywood narratives, and coming at the start of the 1950s it’s arguably emblematic of the oppositional relationship many ‘adult’ Westerns of that era took towards the conventions of previous examples of the genre. Interestingly, and against the conventions established in many Hollywood films, Rawhide depicts in painstaking detail the effort Tom and Vinnie go to in an attempt to dig a hole through the wall of room in the stagecoach station in which they have been trapped by Zimmermann, only for this escape route never to be used by the pair. The use of the knife to dig through the wall is shown in shots that approximate the ‘cinema of process’ that has been seen in, for example, the incredible detail with which the heist is shown in Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955). Colin McArthur originated the term ‘cinema of process’ in reference to Jean-Pierre Melville’s crime films of the late 1960s and early 1970s (for example, Le cercle rouge, 1970), describing Melville’s ‘cinema of process’ as ‘a cinema which went some way to honouring the integrity of actions by allowing them to happen in a way significantly closer to “real” time than was formerly the case in fictive, particularly Hollywood, cinema’ (McArthur, 2000: 191). MacArthur suggests that the ‘cinema of process’ grew out of Dassin’s depiction of the heist in Rififi. However, Rawhide’s depiction of Vinnie and Tom’s attempt to dig through the wall feels like an earlier example of this method, the scenes feeling almost as if they are shot in ‘real time’ as Hathaway cuts from either Tom or Vinnie under the table as they attempt to use the knife to chip away at the wall, to the other of the pair standing guard near the door and listening for Zimmermann or Tevis. The digging of this hole is shown with the same amount of detail as an audience might associated with jailbreak stories: for example, the digging of the holes intended to be used as escape routs in Jacques Becker’s Le trou (1960), The Great Escape (John Sturges, 1963) or Escape from Alcatraz (Don Siegel, 1979). However, unlike in those films, the escape route is never used for its intended purpose. It’s an interesting subversion of the paradigms of Hollywood narratives, and coming at the start of the 1950s it’s arguably emblematic of the oppositional relationship many ‘adult’ Westerns of that era took towards the conventions of previous examples of the genre.

Video

Taking up just over 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Signal One’s 1080p presentation of Rawhide uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 86:37 mins, and is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The original 35mm monochrome photography is communicated excellently in this presentation. Fine detail is present throughout, and contrast levels are balanced superbly – with rich and defined midtones countered by balanced highlights and deep blacks. Some minor damage is present throughout the film in the form of small flecks and specks – but nothing distracting. The film uses much staging in depth, small apertures used to ensure foreground and background action is visible in many of the the exterior scenes; this sense of depth in the original photography is communicated very well in this digital presentation. There is no evidence of harmful digital tinkering, and a very robust encode ensures that the structure of 35mm film is present throughout. Taking up just over 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Signal One’s 1080p presentation of Rawhide uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 86:37 mins, and is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The original 35mm monochrome photography is communicated excellently in this presentation. Fine detail is present throughout, and contrast levels are balanced superbly – with rich and defined midtones countered by balanced highlights and deep blacks. Some minor damage is present throughout the film in the form of small flecks and specks – but nothing distracting. The film uses much staging in depth, small apertures used to ensure foreground and background action is visible in many of the the exterior scenes; this sense of depth in the original photography is communicated very well in this digital presentation. There is no evidence of harmful digital tinkering, and a very robust encode ensures that the structure of 35mm film is present throughout.

NB. Larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track is deep and rich, dialogue being audible throughout, and the subtitles are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes:  - An audio commentary by C Courtney Joyner. Joyner introduces himself as a ‘great Henry Hathaway enthusiast’, and this enthusiasm shines through in his commentary for this picture. The commentary track is filled with anecdotes and reflections on Hathaway’s approach to filmmaking. Joyner describes the film as a ‘cross-genre of Western, crime and prison break’, and he discusses how the picture challenges Power’s screen image and reinforces Hayward’s presence as a ‘strong’ woman. - An audio commentary by C Courtney Joyner. Joyner introduces himself as a ‘great Henry Hathaway enthusiast’, and this enthusiasm shines through in his commentary for this picture. The commentary track is filled with anecdotes and reflections on Hathaway’s approach to filmmaking. Joyner describes the film as a ‘cross-genre of Western, crime and prison break’, and he discusses how the picture challenges Power’s screen image and reinforces Hayward’s presence as a ‘strong’ woman.

- ‘Susan Hayward: Hollywood’s Straight Shooter’ (6:55). This short featurette focuses on Hayward’s status as ‘the embodiment of the strong woman’ who could ‘be in the middle of a male-dominated picture and still command all the attention’. The focus is on Hayward’s screen persona as the ‘feisty’ woman, with discussion of how Hayward’s character in Rawhide was rewritten to make her ‘more gutsy’. Hayward had the original actor who was cast to play Tevis replaced with Jack Elam after the original actor hurt Hayward during a stunt. Comments are provided from David Thompson, Hayward’s biographer Gene Arceri, film historians Larry Swindell and Aubrey Solomon; the featurette appeared previously on Fox’s R1 DVD release of Rawhide in the ‘Fox Western Classics’ boxed set. - ‘Shoot It in Lone Pine!’ (12:38). In this featurette, the long-standing importance of Lone Pine as a location for shooting Westerns is examined. Emphasis is placed on how ‘realistic’ Lone Pine could appear in such films. Commentators include Chris Langley, Director of the Museum of Lone Pine Film History; Aubrey Solomon; Gene Arceri; David Thompson; and film historian Rudy Rehlmer. This featurette also previously appeared on the R1 DVD release of Rawhide from Fox. - Poster and Stills Gallery (1:03). - Trailer (2:26).

Overall

An exciting film, Rawhide is a clear example of the ‘adult’ Westerns that became increasingly popular throughout the 1950s; like Pursued and Blood on the Moon, Rawhide may be considered as much a film noir as a Western. The film’s focus on the taking of hostages and the ensuant battle of wits within a stagecoach station is a recurring narrative within Westerns, from The Tall T (and Day of the Outlaw, which widens the location to a snowbound town rather than just a stagecoach station) and Prega il morto e ammazza il vivo to the recent The Hateful Eight. Power, Marlowe and Hayward are very good here, but the film is arguably stolen by Jack Elam’s slimy turn as the cruel villain Tevis. An exciting film, Rawhide is a clear example of the ‘adult’ Westerns that became increasingly popular throughout the 1950s; like Pursued and Blood on the Moon, Rawhide may be considered as much a film noir as a Western. The film’s focus on the taking of hostages and the ensuant battle of wits within a stagecoach station is a recurring narrative within Westerns, from The Tall T (and Day of the Outlaw, which widens the location to a snowbound town rather than just a stagecoach station) and Prega il morto e ammazza il vivo to the recent The Hateful Eight. Power, Marlowe and Hayward are very good here, but the film is arguably stolen by Jack Elam’s slimy turn as the cruel villain Tevis.

With some beautiful monochrome photography, Rawhide benefits from an excellent presentation on Signal One Entertainment’s new Blu-ray release – one of many deeply impressive releases from this company. The film is accompanied by some excellent contextual material too, making this a must buy for enthusiasts of classic Westerns. References Johnson, Erskine, 1950a: ‘Amazing Susan’. Cumberland Evening Times (8 March, 1950): 14 Johnson, Erskine, 1950b: ‘In Hollywood’. San Bernadino Daily (18 March, 1950): 4 McArthur, Colin, 2000: ‘Mise-en-scène degree zero: Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967)’. In: Hayward, Susan & Vincendeau, Ginette (eds), 2000: French Film: Texts and Contexts. London: Routledge: 189-201 Morfin, Charles Michael, 2014: Images of America: Location Filming in the Alabama Hills. Arcadia Publishing

|

|||||

|