|

|

Between Heaven and Hell (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (16th March 2017). |

|

The Film

Between Heaven and Hell (Richard Fleischer, 1956) Between Heaven and Hell (Richard Fleischer, 1956)

Adapted from the novel The Day the Century Ended by Francis Gwaltney, Richard Fleischer’s Between Heaven and Hell (1956) focuses on Sam Gifford (Robert Wagner). A cotton plantation owner from Gray’s Landing, in civilian life Gifford regarded the sharecroppers on his land with scorn, something which caused friction between Sam and his beautiful wife Jenny (Terry Moore). However, when his National Guard unit is mobilised to fight in the Philippines following the attack on Pear Harbor, Sam finds his attitudes challenged when he faces combat alongside men who identify themselves as sharecroppers. Sam soon proves himself to be a hero, destroying a machine gun nest dug into a cliff-face singlehandedly when he is lowered into the maw of the nest by rope, using grenades to kill the Japanese troops within it. For this, Sam earns the Silver Star. When Sam’s superior officer and father-in-law, Colonel Cozzens (Robert Keith), is shot and killed by a sniper, Sam finds himself stationed under Colonel Miles (Frank Gerstle). On patrol in an abandoned village alongside three of his newfound sharecropper friends, Sam is almost killed when his jittery Lieutenant opens fire unnecessarily, shooting and killing all three of the sharecroppers. Angrily, Sam approaches the Lieutenant and socks him with the stock of his rifle, almost killing the officer. For this, Sam is placed in the stockade and threatened with a court martial. However, Colonel Miles suggests that the army cannot court martial Sam owing to his service record; and instead, Sam is sent to George Company, which is stationed at an isolated outpost which is cut off from the main military force.  At George Company’s base, Sam discovers that he is stationed under the cruel Captain ‘Waco’ Grimes (Broderick Crawford). Waco refuses to wear his officer’s uniform for fear of making himself a target for Japanese snipers, and he spends all of his time in a hut surrounded by sycophants who reinforce his orders with the threat of violence. Waco ridicules Sam through insisting on addressing him by his middle-name ‘Francis’, and he sends Sam and a group of other soldiers on a useless patrol to ‘count the beer cans’ in an abandoned village behind enemy lines. At George Company’s base, Sam discovers that he is stationed under the cruel Captain ‘Waco’ Grimes (Broderick Crawford). Waco refuses to wear his officer’s uniform for fear of making himself a target for Japanese snipers, and he spends all of his time in a hut surrounded by sycophants who reinforce his orders with the threat of violence. Waco ridicules Sam through insisting on addressing him by his middle-name ‘Francis’, and he sends Sam and a group of other soldiers on a useless patrol to ‘count the beer cans’ in an abandoned village behind enemy lines.

Waco is surprised when Sam and the other soldiers return from this mission, and sends Sam along with some other soldiers – including Sam’s new friend Willie (Buddy Ebsen) – to relieve the soldiers stationed at a lookout post. However, when this lookout post comes under attack, only Sam and Willie are left alive; Willie is badly injured and unable to walk, and the Japanese forces are advancing on their position. Sam makes a desperate, heroic attempt to push through the incoming Japanese troops, with the aim of reaching George Company and sending back help for Willie. The author of the novel on which this film is based, Francis Irby Gwaltney, served as a radio operator in the US Army during the Second World War; Gwaltney was stationed in the Philippines, where he met his friend Norman Mailer. After the war, both men would use their experiences in the Pacific Theatre as raw material for their novels: Mailer would, of course, go on to write his debut novel The Naked and the Dead (1948), and Gwaltney used the Pacific Theatre as the focus for The Day the Century Ended, which was adapted as Between Heaven and Hell (and was reprinted under that title following the film’s release). Like Mailer’s novel, Gwaltney’s book was forthright in its representation of combat and its use of language amongst the soldiers – but where Mailer used the word ‘fug’ as a substitute for ‘fuck’ in order to appease more censorious mindsets, Gwaltney’s novel was more direct, simply removing the ‘c’ from the word ‘fuck’, using ‘fuk’ instead. Minus the strong language and a finale which includes the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Gwaltney’s novel was adapted into screenplay form by Harry Brown, the novelist who wrote A Walk in the Sun (1944, itself adapted into a film by Lewis Milestone in 1945).  The film begins with Sam placed in the stockade, from which he is brought to Colonel Miles. Miles reveals that Sam will be placed with George Company instead of being court martialled. The reason why Sam was in the stockade is unclear for a good portion of the film’s running time, the narrative teasing this information out via a series of extended flashbacks which fragment the narrative and disrupt the diegetic present with glimpses of a more outwardly ‘simple’ past life. These flashbacks show, firstly, Sam’s life back home at Gray’s Landing, his treatment of the sharecroppers and his disagreement with Jenny over how he speaks to the croppers; and secondly, Sam’s experiences following the mobilisation of his National Guard unit to the Philippines, their transportation via ship, Sam’s act of bravery for which he earns his Silver Star, the shooting and killing of Colonel Cozzens by a Japanese sniper, Sam’s growing friendship with a group of croppers with whom he has been stationed, and finally the incident for which he has been threatened with court martial (Sam’s attacking of a lieutenant following the moment in which the officer shoots and kills three of Sam’s comrades). The film begins with Sam placed in the stockade, from which he is brought to Colonel Miles. Miles reveals that Sam will be placed with George Company instead of being court martialled. The reason why Sam was in the stockade is unclear for a good portion of the film’s running time, the narrative teasing this information out via a series of extended flashbacks which fragment the narrative and disrupt the diegetic present with glimpses of a more outwardly ‘simple’ past life. These flashbacks show, firstly, Sam’s life back home at Gray’s Landing, his treatment of the sharecroppers and his disagreement with Jenny over how he speaks to the croppers; and secondly, Sam’s experiences following the mobilisation of his National Guard unit to the Philippines, their transportation via ship, Sam’s act of bravery for which he earns his Silver Star, the shooting and killing of Colonel Cozzens by a Japanese sniper, Sam’s growing friendship with a group of croppers with whom he has been stationed, and finally the incident for which he has been threatened with court martial (Sam’s attacking of a lieutenant following the moment in which the officer shoots and kills three of Sam’s comrades).

Between Heaven and Hell was one of a number of 1950s American war pictures which acknowledged and even foregrounded the psychological trauma of war upon its participants; these films included Robert Aldrich’s Attack! (1956) and Sam Fuller’s war pictures The Steel Helmet (1951) and Fixed Bayonets! (1951). The hardboiled tone of much of Between Heaven and Hell (leaving aside the flashback sequences which evidence a nostalgia for the prewar era that was almost a prerequisite for Hollywood combat films of the 1950s) gives the picture a strong similarity to Fuller’s unrepentant, slyly subversive war films. These were pictures which downplayed the heroics of the more conventional Hollywood war film and highlighted the conflict between those issuing commands and those who must obey them; in the. In Between Heaven and Hell, Sam Gifford’s response to combat is a dose of ‘the shakes’ – a physiological sign of combat fatigue. We are shown Sam pleading, after a firefight has ended, ‘No more. Please, no more’; following the film’s final scene of combat, Willie only manages to talk Sam down from his precipice of fear by discussing ‘back home’ and jokingly asking Sam for a job as a truck driver. However, where a more jingoistic combat picture might suggest that Sam’s evidencing of ‘the shakes’ is a symbol of cowardice, Between Heaven and Hell takes every opportunity to establish Sam’s bravery and selflessness – in this picture, Sam’s combat fatigue is shown to be nothing to be ashamed of, simply a logical response to circumstances of extreme psychological stress and trauma.  The title, ‘Between Heaven and Hell’, suggests that presided over by the corrupt Waco, Sam’s stationing with the isolated George Company is a form of Purgatory, in which Sam is purged of his sins before returning to Heaven at the end of the picture when, wounded in battle, he is promised that he will return home to Gray’s Landing alongside Willie – who has also been badly wounded. Sam’s ‘sin’ lies in his treatment, as the owner of a cotton plantation, of those he regards as beneath him. The extended flashbacks towards the start of the picture show Sam engaged in dialogue with Jenny, his coarse behaviour towards the sharecroppers challenged by his wife; these scenes are almost didactic in their outlining of the conflict between Sam’s cruel, sneering attitude towards the sharecroppers and Jenny’s more humanistic, egalitarian outlook. ‘Why do you talk that way? [….] The way you talk to these people?’, Jenny asks after Sam has taken her on a visit to the croppers on his plantation. ‘You mean there’s another way?’, Sam asks, ‘They’re lazy. They have to be kept jumpin’. They have to be kept in their place’. ‘They’re human beings, Sam’, Jenny protests, ‘Can’t you understand that? [….] I don’t think business gives anyone a right to be rude. If that’s the way businessmen act, then I’m glad I’m a woman’. In combat alongside men who in his civilian life he regarded as his underlings, treating them in the words of Jenny as little better than farming machinery, Sam comes to realise the similarities between himself and the sharecroppers: he is purged of his prejudices against them. At the end of the film, when Sam and Willie are left alone, the sole survivors of an assault by Japanese troops on the observation post, Willie asks Sam, ‘You a rich man, Sam? [….] How’s it feel?’ ‘I don’t know’, Sam says, ‘Right now it doesn’t make a difference’. ‘I always wished I had money’, Willie tells his friend. ‘Maybe you will’, Sam responds. ‘Naw’, Willie says, ‘I ain’t nothin’ but a sharecropper’. ‘Croppers will be better off after the war’, Sam says. ‘You think so?’, Willie asks. ‘Mine will, that’s for sure’, Sam tells him. The title, ‘Between Heaven and Hell’, suggests that presided over by the corrupt Waco, Sam’s stationing with the isolated George Company is a form of Purgatory, in which Sam is purged of his sins before returning to Heaven at the end of the picture when, wounded in battle, he is promised that he will return home to Gray’s Landing alongside Willie – who has also been badly wounded. Sam’s ‘sin’ lies in his treatment, as the owner of a cotton plantation, of those he regards as beneath him. The extended flashbacks towards the start of the picture show Sam engaged in dialogue with Jenny, his coarse behaviour towards the sharecroppers challenged by his wife; these scenes are almost didactic in their outlining of the conflict between Sam’s cruel, sneering attitude towards the sharecroppers and Jenny’s more humanistic, egalitarian outlook. ‘Why do you talk that way? [….] The way you talk to these people?’, Jenny asks after Sam has taken her on a visit to the croppers on his plantation. ‘You mean there’s another way?’, Sam asks, ‘They’re lazy. They have to be kept jumpin’. They have to be kept in their place’. ‘They’re human beings, Sam’, Jenny protests, ‘Can’t you understand that? [….] I don’t think business gives anyone a right to be rude. If that’s the way businessmen act, then I’m glad I’m a woman’. In combat alongside men who in his civilian life he regarded as his underlings, treating them in the words of Jenny as little better than farming machinery, Sam comes to realise the similarities between himself and the sharecroppers: he is purged of his prejudices against them. At the end of the film, when Sam and Willie are left alone, the sole survivors of an assault by Japanese troops on the observation post, Willie asks Sam, ‘You a rich man, Sam? [….] How’s it feel?’ ‘I don’t know’, Sam says, ‘Right now it doesn’t make a difference’. ‘I always wished I had money’, Willie tells his friend. ‘Maybe you will’, Sam responds. ‘Naw’, Willie says, ‘I ain’t nothin’ but a sharecropper’. ‘Croppers will be better off after the war’, Sam says. ‘You think so?’, Willie asks. ‘Mine will, that’s for sure’, Sam tells him.

Waco offers a dark shadow of Sam. Waco treats the soldiers in his command in a similar manner to which Sam treated his sharecroppers. Towards the end of the film, Waco highlights the similarities between himself and Sam which have been built slowly as the narrative progresses: during their first meeting, Waco asks to see the photograph of Jenny that Sam carries, telling Sam that his wife is ‘pretty’ before saying that he himself has a similarly pretty wife back home”: ‘You got a pretty wife, Gifford’, Waco says, ‘I got a pretty wife. About the prettiest wife in Waco, Texas. I bet she’s runnin’ around with all the guys in town’. Waco then proceeds to burn Sam’s photograph of Jenny in an attempt to sever Sam’s ties with his past. In the film’s final sequences, Waco returns to the similarities between himself and Sam, telling Sam that he too was awarded a merit for an act of bravery before being busted for an act of insubordination. In this way, the film suggest subtly that Waco is the man Sam could have become if he hadn’t rid himself of the haughty, self-regarding worldview with which he was associated in civilian life.  Robert Eberwein highlights the similarities between Waco, in Between Heaven and Hell, and General Cummings (Raymond Massey) in Raoul Walsh’s 1958 film adaptation of The Naked and the Dead: both officers, Eberwein says, ‘represent potential dangers to the men under them because of their personal psychological problems’ (Eberwein, 2007: 76). Waco presides over George Company as if it were a medieval fiefdom, surrounding himself with sycophants who consolidate Waco’s tyrannical reign over his men and reinforce it with the threat of violence. At the end of the film, Waco argues that his cruel outlook has been forged by combat: ‘A man can stand so much. Then he ain’t a man anymore’, Waco says, in one of the film’s most polemic lines of dialogue. Waco’s presumed cowardice, represented in his refusal to wear his officer’s uniform or step foot outside the hut that has become his command post for fear of making himself a target for Japanese snipers, is a contrasted with Sam’s combat fatigue (shown through Sam’s suffering of ‘the shakes’ after combat situations); however, where Sam steps up to the mark and commits himself to combat, Waco avoids it at all costs. Waco’s fear of snipers is consolidated for the film’s audience by the scene we see, in one of the flashbacks, of Colonel Cozzens being killed by a sniper. Waco’s approach to the command of his troops is in contrast with Cozzens’ more softly-softly methods; Colonel Miles represents a mediation between the harsh, cruel methods of Waco and the gentle touch of Cozzens. (Gwaltney’s source novel is more forthright in criticising Cozzens’ more populist but arguably just as ineffective command of his troops, suggesting that Cozzens’ gentle handling of the men under his command would fall apart when the fighting with the Japanese troops would become more heated and close-in.) Ironically, Waco’s fears appear to be grounded when, in the film’s final sequence, his is relieved of his command by Colonel Miles and, dressed in his officer’s uniform, climbs into his jeep to leave the base of George Company; a shot rings out and the camera reveals Waco to have been shot through the head, his helmet providing almost no protection. Waco’s fate is thus identical to that of Colonel Cozzens and somewhat validates Waco’s previously expressed fear of being made a target for snipers. Robert Eberwein highlights the similarities between Waco, in Between Heaven and Hell, and General Cummings (Raymond Massey) in Raoul Walsh’s 1958 film adaptation of The Naked and the Dead: both officers, Eberwein says, ‘represent potential dangers to the men under them because of their personal psychological problems’ (Eberwein, 2007: 76). Waco presides over George Company as if it were a medieval fiefdom, surrounding himself with sycophants who consolidate Waco’s tyrannical reign over his men and reinforce it with the threat of violence. At the end of the film, Waco argues that his cruel outlook has been forged by combat: ‘A man can stand so much. Then he ain’t a man anymore’, Waco says, in one of the film’s most polemic lines of dialogue. Waco’s presumed cowardice, represented in his refusal to wear his officer’s uniform or step foot outside the hut that has become his command post for fear of making himself a target for Japanese snipers, is a contrasted with Sam’s combat fatigue (shown through Sam’s suffering of ‘the shakes’ after combat situations); however, where Sam steps up to the mark and commits himself to combat, Waco avoids it at all costs. Waco’s fear of snipers is consolidated for the film’s audience by the scene we see, in one of the flashbacks, of Colonel Cozzens being killed by a sniper. Waco’s approach to the command of his troops is in contrast with Cozzens’ more softly-softly methods; Colonel Miles represents a mediation between the harsh, cruel methods of Waco and the gentle touch of Cozzens. (Gwaltney’s source novel is more forthright in criticising Cozzens’ more populist but arguably just as ineffective command of his troops, suggesting that Cozzens’ gentle handling of the men under his command would fall apart when the fighting with the Japanese troops would become more heated and close-in.) Ironically, Waco’s fears appear to be grounded when, in the film’s final sequence, his is relieved of his command by Colonel Miles and, dressed in his officer’s uniform, climbs into his jeep to leave the base of George Company; a shot rings out and the camera reveals Waco to have been shot through the head, his helmet providing almost no protection. Waco’s fate is thus identical to that of Colonel Cozzens and somewhat validates Waco’s previously expressed fear of being made a target for snipers.

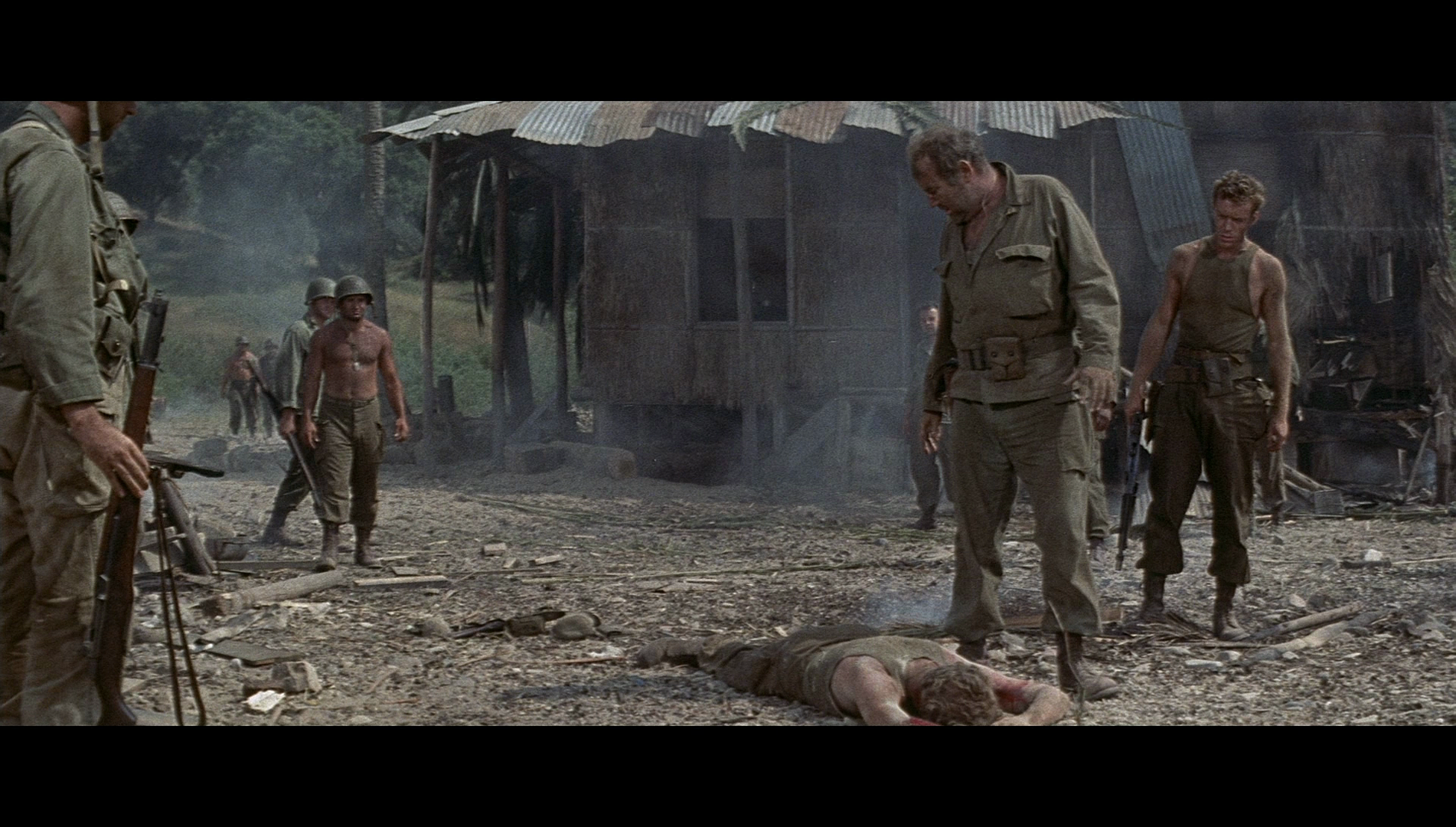

Hugo Friedhofer’s score for the film uses motifs based on Hector Berlioz’s orchestral setting of ‘Dies Irae’ (‘Day of Wrath’), the Gregorian chant for the dead. (Over twenty years later, the haunting potential of this piece of music was underscored by its use in Wendy Carlos’ score for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, 1979.) In Between Heaven and Hell, the melody of ‘Dies Irae’ is used incredibly effectively, giving the film’s moments of action a haunting undercurrent: Friedhofer rearranges ‘Dies Irae’ into a militaristic march for the some sequences, and also uses the melody in his music for the film’s scenes of action. The use of ‘Dies Irae’, an arrangement about the Day of Reckoning, gives the picture a sense of finality and an almost apocalyptic quality – much like Wendy Carlos’ appropriation of the same melody in her score for The Shining. The underrepresentation of Friedhofer’s work on home listening formats, and amongst the discussions of cinephiles, is a crying shame; certainly, in the case of Between Heaven and Hell much of the weight of the picture arguably comes from Friedhofer’s arrangement of the ‘Dies Irae’ and its employment alongside the photography – which makes extremely effective use of the widescreen frame. Fritz Lang famously asserted, in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le mepris (1961), that Cinemascope was only good for shooting snakes or funerals; the photography in Between Heaven and Hell makes superb use of the extra space along the horizontal axis of the frame, filling it with bodies lying in the sun or the rifles that the men are firing at their enemy. It’s the kind of widescreen photography that died out in the era of television and home video, when compositions were often compromised with the knowledge that they would be cropped for television broadcast or for release on videocassette. Hugo Friedhofer’s score for the film uses motifs based on Hector Berlioz’s orchestral setting of ‘Dies Irae’ (‘Day of Wrath’), the Gregorian chant for the dead. (Over twenty years later, the haunting potential of this piece of music was underscored by its use in Wendy Carlos’ score for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, 1979.) In Between Heaven and Hell, the melody of ‘Dies Irae’ is used incredibly effectively, giving the film’s moments of action a haunting undercurrent: Friedhofer rearranges ‘Dies Irae’ into a militaristic march for the some sequences, and also uses the melody in his music for the film’s scenes of action. The use of ‘Dies Irae’, an arrangement about the Day of Reckoning, gives the picture a sense of finality and an almost apocalyptic quality – much like Wendy Carlos’ appropriation of the same melody in her score for The Shining. The underrepresentation of Friedhofer’s work on home listening formats, and amongst the discussions of cinephiles, is a crying shame; certainly, in the case of Between Heaven and Hell much of the weight of the picture arguably comes from Friedhofer’s arrangement of the ‘Dies Irae’ and its employment alongside the photography – which makes extremely effective use of the widescreen frame. Fritz Lang famously asserted, in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le mepris (1961), that Cinemascope was only good for shooting snakes or funerals; the photography in Between Heaven and Hell makes superb use of the extra space along the horizontal axis of the frame, filling it with bodies lying in the sun or the rifles that the men are firing at their enemy. It’s the kind of widescreen photography that died out in the era of television and home video, when compositions were often compromised with the knowledge that they would be cropped for television broadcast or for release on videocassette.

Video

The film is uncut, with a running time of 93:43 mins. Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Signal One Entertainment’s presentation of Between Heaven and Hell is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Aside from the opening shots, which are optically printed and in slightly rough shape, the image is crisp and evidences plenty of fine detail – including beads of sweat on the brows of the actors. Contrast levels are very pleasing; most of the film is shot under the blazing sun, with bright sunlight illuminating the faces of the actors and dark shadows cast behind them; the contrast levels in this presentation communicate this superbly, with deep, deep blacks and midtones that have a strong sense of definition balanced by careful handling of the highlights. Some minor damage, in the form of white flecks and specks on the image which suggest debris on the negative, is present here and there – but nothing too distracting. A superb encode ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. The film is uncut, with a running time of 93:43 mins. Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Signal One Entertainment’s presentation of Between Heaven and Hell is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Aside from the opening shots, which are optically printed and in slightly rough shape, the image is crisp and evidences plenty of fine detail – including beads of sweat on the brows of the actors. Contrast levels are very pleasing; most of the film is shot under the blazing sun, with bright sunlight illuminating the faces of the actors and dark shadows cast behind them; the contrast levels in this presentation communicate this superbly, with deep, deep blacks and midtones that have a strong sense of definition balanced by careful handling of the highlights. Some minor damage, in the form of white flecks and specks on the image which suggest debris on the negative, is present here and there – but nothing too distracting. A superb encode ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 track. This is clear throughout, the depth of the music being communicated effectively and sound effects (such as gunshots) being given a strong sense of depth too. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included; these are free from errors and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: - An audio commentary with Paul Talbot. Here, Talbot, the author of Bronson’s Loose: The Making of the Death Wish Films and Bronson’s Loose Again: On Set With Charles Bronson, enthuses about the work of Richard Fleischer. Talbot previously provided a commentary for Signal One’s previous release of Fleischer’s Charles Bronson-starring picture Mr Majestyk (1974, reviewed by us here). Talbot’s commentary is breathless and well-researched, packed with enthusiastic detail about the work of a filmmaker whom Talbot interviewed for his 2009 book Mondo Mandingo. Talbot highlights elements of technique familiar from Fleischer’s other pictures and discusses the film’s casting, reflecting on the film’s relationship with its source novel and its connections with other combat pictures of the era. It’s an enthusiastic and enlightening commentary track, well worth a listen for those interested in this era of Hollywood filmmaking, the work of Fleischer or the US combat film. - A stills gallery (0:21). - The film’s trailer (2:26).

Overall

Between Heaven and Hell is a fascinating, exciting film; like many of the 1950s war pictures in the hardboiled strand (such as Samuel Fuller’s films), Between Heaven and Hell represents war as an equalizer, stripping away socio-economic differences in the heat of battle. The sense of George Company, and by extension the war itself, as a form of Purgatory is reinforced by Friedhofer’s use of melodies based on the Catholic chant ‘Dies Irae’ in the film’s score; the use of this melody, about the Day of Judgement, gives the allusion to the concept of Purgatory within the film’s title a sense of depth and communicates an almost apocalyptic view of warfare. (In this sense, the picture feels like a precursor to more outwardly symbolic Vietnam-era anti-war films such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, 1979.) The juxtaposition of Waco and Cozzens (a contrast reinforced by the fact that both men share the same fate within the film), and the suggestion that Waco is the man that Gifford could have become, also gives the film a strong resonance. Only the early flashback sequences to Sam’s seemingly idyllic past and his relationship with Jenny, something which was a paradigm of 1950s combat pictures, threaten to slow the pace and drag the film downwards; however, even these contain a strong sense of irony, the film soon showing that the purpose of including these flashbacks was to underscore the extent to which the trials of combat purge Sam of his previously held prejudices. Between Heaven and Hell is a fascinating, exciting film; like many of the 1950s war pictures in the hardboiled strand (such as Samuel Fuller’s films), Between Heaven and Hell represents war as an equalizer, stripping away socio-economic differences in the heat of battle. The sense of George Company, and by extension the war itself, as a form of Purgatory is reinforced by Friedhofer’s use of melodies based on the Catholic chant ‘Dies Irae’ in the film’s score; the use of this melody, about the Day of Judgement, gives the allusion to the concept of Purgatory within the film’s title a sense of depth and communicates an almost apocalyptic view of warfare. (In this sense, the picture feels like a precursor to more outwardly symbolic Vietnam-era anti-war films such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, 1979.) The juxtaposition of Waco and Cozzens (a contrast reinforced by the fact that both men share the same fate within the film), and the suggestion that Waco is the man that Gifford could have become, also gives the film a strong resonance. Only the early flashback sequences to Sam’s seemingly idyllic past and his relationship with Jenny, something which was a paradigm of 1950s combat pictures, threaten to slow the pace and drag the film downwards; however, even these contain a strong sense of irony, the film soon showing that the purpose of including these flashbacks was to underscore the extent to which the trials of combat purge Sam of his previously held prejudices.

Where, for Waco, ‘A man can stand so much. Then he ain’t a man anymore’, for Sam combat and his experiences within it (‘What changed your mind?’, Willie asks; ‘Oh, people. What they’re doin’ for me’, Sam tells him) push him towards becoming a better man, with the promise that he will return to Gray’s Landing with a more egalitarian worldview and will adopt a more humanitarian approach to his sharecroppers. Sam will return from combat not the same man that he was before, his nostalgic view of his prewar life undercut by his realisation of how cruelly he treated his croppers, but certainly a better man – albeit one who has suffered through combat fatigue and hardships that will be impossible to share with his beloved wife. Signal One Entertainment’s presentation of the film is, the rough-looking optically printed shots that open the film aside, superb, the transfer handling the harsh light within the original photography (with its juxtaposition of strong illumination and deep shadow often within the same shot) very pleasingly. The excellent presentation of the main feature is complemented by an enthusiastic and information-packed audio commentary with Paul Talbot. It’s a very good release of an often overlooked war picture. References: Eberwein, Robert, 2007: Armed Forces: Masculinity and Sexuality in the American War Film. Rutgers University Press

|

|||||

|