|

The Film

The Creeping Garden (Tim Grabham & Jasper Sharp, 2014) The Creeping Garden (Tim Grabham & Jasper Sharp, 2014)

In an essay about The Creeping Garden (2014) published in the book Advances in Physarum Machines (2016), the film’s co-director Jasper Sharp suggests that The Creeping Garden is ‘a rare example of an independently-produced feature-length documentary intended for a general audience that focuses on scientific subject matter’ (Sharp, 2016: 789). As Sharp says in his piece, most modern documentaries tend to privilege ‘social campaigning or character-driven narratives’ (ibid.: 791). Certainly, the film’s focus on myxomycetes (slime moulds) is uncommon, but The Creeping Garden also demonstrates an equal fascination in how the world of these ‘invisible’ organisms may be, and has been, documented visually.

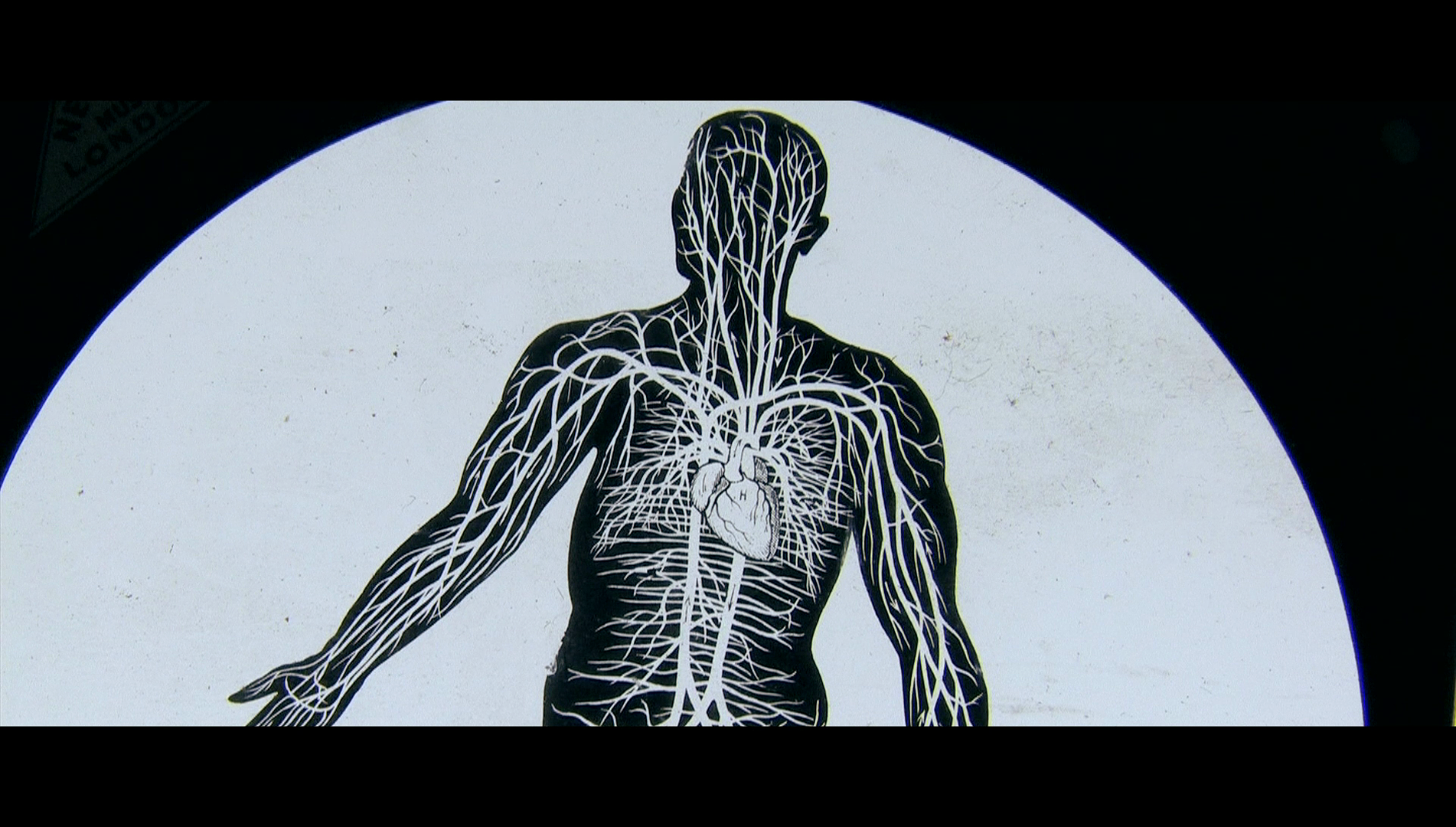

The Creeping Garden examines the world of slime moulds via the use of time-lapse photography (capturing the growth and expansion of slime moulds), CGI (depicting changes to these organisms on a cellular level), interviews with various participants and shots of nature: the film begins with the camera racing across grass at a low level, before plunging beneath the surface, the image segueing seamlessly into CGI depicting micro-organisms and cells on a microscopic perspective.

The participants include Mark Pagnell, an amateur naturalist who we see foraging through woodland, photographing slime moulds whilst via offscreen narration he explains his pastime (‘I’ve always liked being out in the woods, like [….] Mainly looking for mushrooms, though, with a sideline of slime moulds’). Mark’s observations about slime moulds are followed by those of Bryn Dentinger, the Senior Research Leader of Comparative Fungal Biology at Kew Gardens. Bryn praises the resilience of slime moulds, reminding us that ‘Clearly they have evolved the capacity to live out of very hostile conditions’.

Artist Heather Barnett is shown producing her work which focuses on capturing slime moulds in time-lapse photography (eg, spreading through a maze to reach a food source – usually an oat – placed within it) and translating this into art. Heather insists that slime moulds exhibit organised behaviour when faced with repellents or attractants, and therefore have a sense of intelligence which makes them comparable to an animal. Artist Heather Barnett is shown producing her work which focuses on capturing slime moulds in time-lapse photography (eg, spreading through a maze to reach a food source – usually an oat – placed within it) and translating this into art. Heather insists that slime moulds exhibit organised behaviour when faced with repellents or attractants, and therefore have a sense of intelligence which makes them comparable to an animal.

At the Science Museum Storage Facility in Blythe House, Tim Boon – the author of Films of Fact: A History of Science in Documentary Films and Television – reflects on the fascination with magic lanterns in the days before cinema, some of which (Tim argues) developed the paradigms that, today, we associate with scientific films. From here, Tim discusses the use of cinema ‘to slow down or to speed up the passage of time’, and he discusses the work of amateur naturalist and filmmaker F Percy Smith, who pioneered the use of time-lapse photography (or ‘time magnification’, as Smith himself called it) in short films such as ‘Magic Myxies’ (1931).

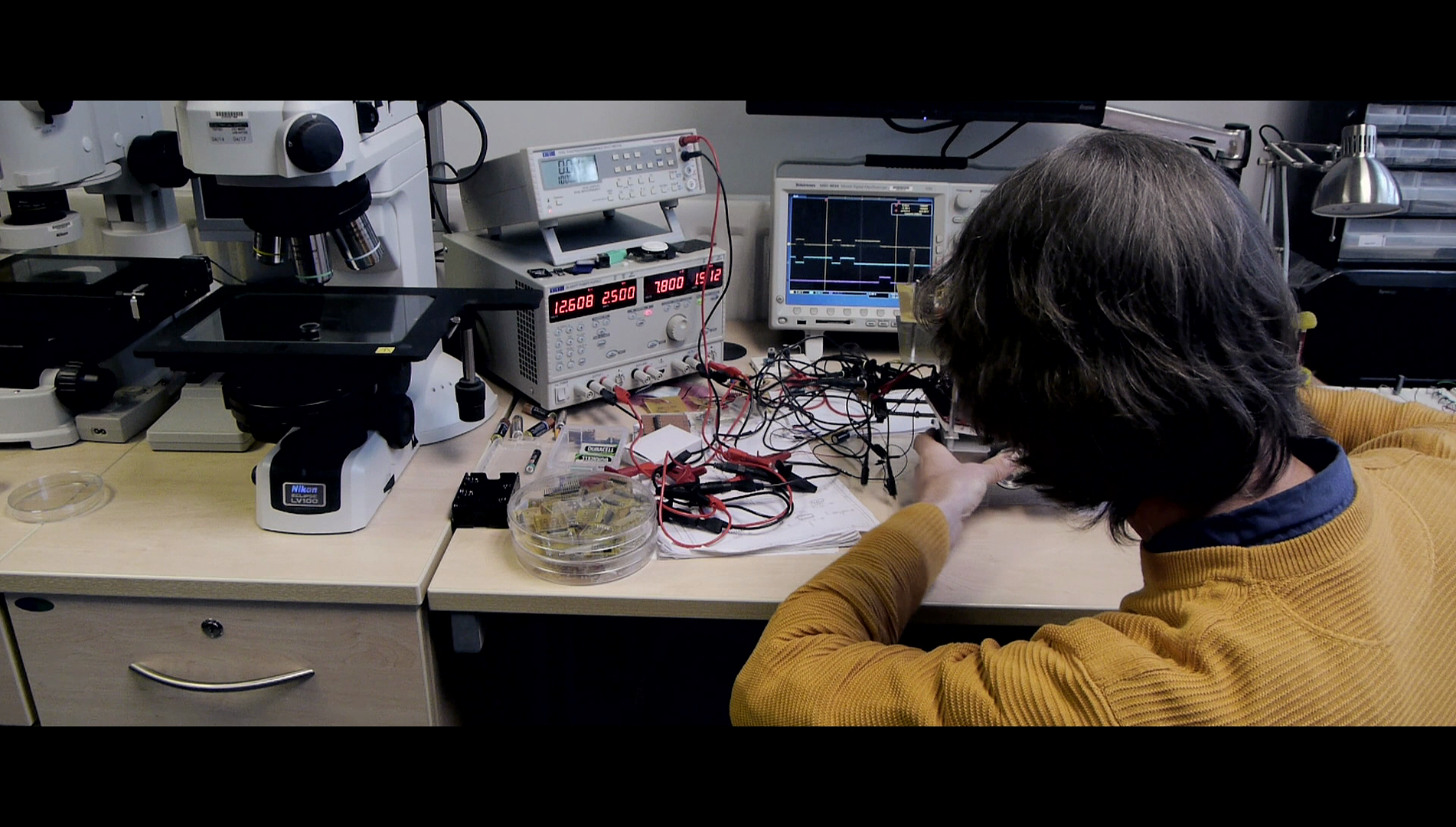

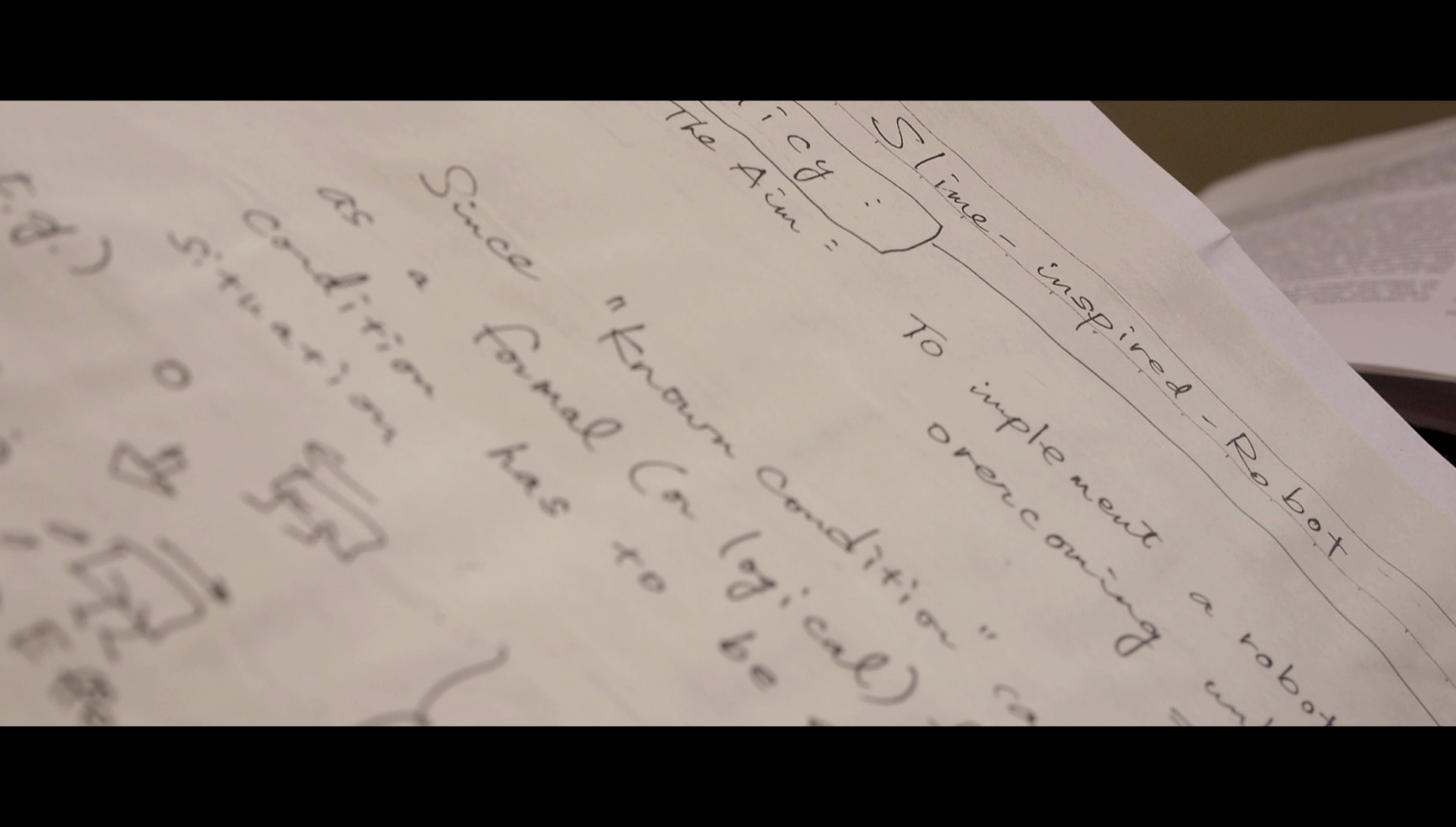

Computer scientist Andrew Adamatzky suggests that if a food source, such as oats, are placed on a map over the spaces where the largest cities would be, the routes that slime moulds take to get from one food source to another correlates very strongly with the network of major roads – suggesting some comparability between the ‘intelligence’ of slime moulds (if it can be referred to as such) and infrastructures created by people. Andrew’s comments are intercut with those of Dr Klaus-Peter Zauner; both are interested in applying what can be learnt from slime moulds to computing and robotics, Zauner building robots which incorporate slime moulds into their circuitry, mapping electronic signals from the slime moulds onto the behaviour of the robots, these signals dictating the robots’ movements. Zauner hopes to move towards ‘a circuit board where one component is a living organism built into the circuit’.

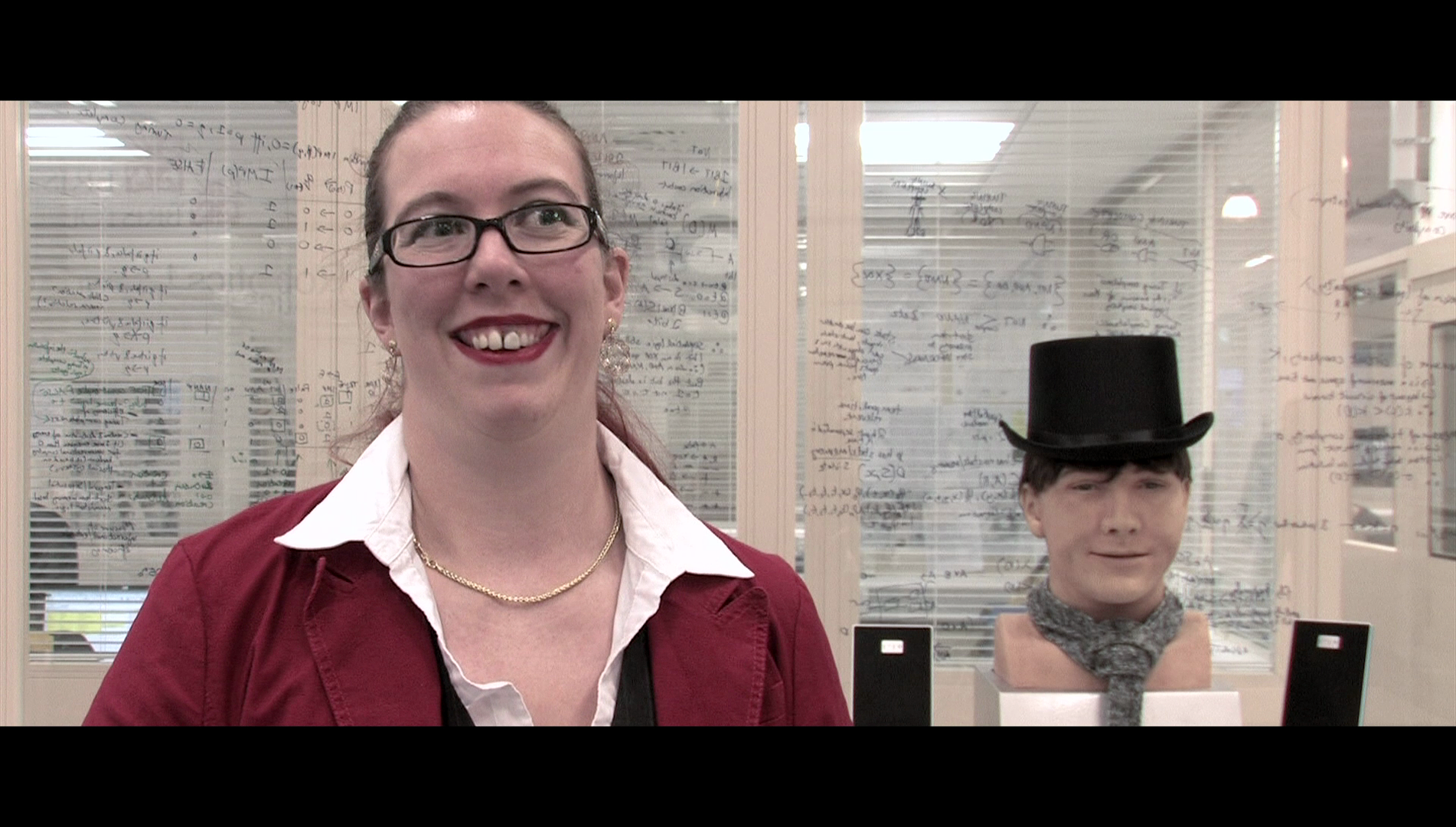

From the worlds of computing and robotics, The Creeping Garden takes us to the world of music, exploring how slime moulds can be used to produce music via the mapping of the oscillations they emit: we are told that they produce ‘happy’ music when provided with humidity and food, and lower oscillations when these stimuli are removed and the slime mould goes into a state of hibernation. Ella Gayle, a researcher at the University of the West of England, shows us how she has mapped similar data onto a robot head which translates these oscillations into human facial expressions denoting specific emotional states (a happy smile; a frown, etc). From the worlds of computing and robotics, The Creeping Garden takes us to the world of music, exploring how slime moulds can be used to produce music via the mapping of the oscillations they emit: we are told that they produce ‘happy’ music when provided with humidity and food, and lower oscillations when these stimuli are removed and the slime mould goes into a state of hibernation. Ella Gayle, a researcher at the University of the West of England, shows us how she has mapped similar data onto a robot head which translates these oscillations into human facial expressions denoting specific emotional states (a happy smile; a frown, etc).

In the aforementioned essay, Sharp suggests that myxomycetes are ‘invisible’ in more than one sense: in a very literal sense, they are largely invisible to the naked eye, except ‘in the mobile plasmodial and sporification (fruiting) phases of their life cycles’ (Sharp, op cit.: 789). One must usually use a microscope in order to see myxomycetes at any other phase in their life cycle. On the other hand, Sharp argues, slime moulds are ‘invisible’ in the sense that, other than alien invasion stories, they are underrepresented in the media and even in the discourse of science. (This is something underscored in the film itself, in a sequence set within the Fungarium at Kew Gardens which highlights just how rarely the slime mould samples contained within the Fungarium are viewed.) Sharp highlights the fact that there is only a single example of a television documentary focusing exclusively on slime moulds: the German documentary Like Nothing on Earth: The Incredible Life of Slime Moulds (ARTE, 2002). Elsewhere, slime moulds have formed the basis for experimental short films and the occasional ‘pedagogical treatments […] targeted at the educational market’ such as Slime Moulds: Life Cycle (1961).

The film makes no hesitation in comparing its focus on slime moulds with the paradigms of science-fiction pictures that feature remarkably similar organisms – particularly alien invasion narratives such as The Blob (Irvin Yeaworth, 1958) and its sequels and remakes. The Creeping Garden begins with an archive news broadcast from NBC in America which covers the appearance of purple ‘blobs’ in Texas in 1973: ‘One grew sixteen times its original size and it turned purple when it was pulped’, the newscaster asserts sensationalistically, ‘Now most of the “blobs” in Texas are dying and we still don’t know what they are’.

Sharp praises co-director Tim Grabham’s ‘stunning cinematography’ (Sharp, op cit.: 798). This photography captures slime moulds both ‘in their natural locales [for example, woodlands where Mark and Heather photograph and gather samples] and in the controlled environment of the Petri dish’ (ibid.). The photography of slime moulds within the natural environment underscores the diversity of this organism: Grabham’s photography captures, via the use of time-lapse, the growth and expansion of several species of slime mould, including Fulgio septica (Dog’s Vomit) and Lycogala epidendrum (Wolf’s Milk). The chief difficulty was photographing organisms which are highly sensitive to light. Sharp praises co-director Tim Grabham’s ‘stunning cinematography’ (Sharp, op cit.: 798). This photography captures slime moulds both ‘in their natural locales [for example, woodlands where Mark and Heather photograph and gather samples] and in the controlled environment of the Petri dish’ (ibid.). The photography of slime moulds within the natural environment underscores the diversity of this organism: Grabham’s photography captures, via the use of time-lapse, the growth and expansion of several species of slime mould, including Fulgio septica (Dog’s Vomit) and Lycogala epidendrum (Wolf’s Milk). The chief difficulty was photographing organisms which are highly sensitive to light.

The documentary intersperses conversations with its various ‘talking heads’ with macro time-lapse footage of slime moulds growing in a natural context or in laboratory circumstances (for example, repeated shots of slime moulds filling the space of a maze in which oats, a food source, have been placed). In fact, the film is as interested in the techniques used to capture the growth and movement of slime moulds as it is in the nature of the slime moulds themselves; one sequence reflects in particular on naturalist and pioneer of the nature documentary F Percy Smith’s development of time-lapse photography and microscopy, and Smith’s employment of these techniques in his films for the British Instructional Films’ Secrets of Nature (later, Secrets of Life) series. This sequence makes The Creeping Garden feel heavily reflexive, foregrounding and reflecting on the techniques employed by the makers of the documentary themselves – though with the aid of modern digital technology which, Sharp acknowledges, made their task much easier than Smith’s (Sharp, op cit.).

Throughout, The Creeping Garden makes consistent use of time-lapse and macro photography, the film often cutting to this footage symbolically (for example, to demonstrate the notion given by some of the interviewees that the movement of slime moulds may be compared to the movement within groups of people). The constant cutting away to shots of slime moulds, accompanied by the eerie electronic music which alludes to the paradigms of 1970s science fiction films about nature gone amok (eg, Saul Bass’ Phase IV, 1974), makes The Creeping Garden feel strongly like a documentary in the poetic mode. The overall effect is of a documentary which emphasises rhythmic, lyrical qualities, creating association between its subject (slime moulds) and related topics (computer circuitry; road networks; the movement of groups of people) through its editing – not dissimilar to Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982). However, where The Creeping Garden differs from Koyaanisqatsi is in The Creeping Garden’s use of narration: where Koyaanisqatsi avoided a guiding human voice, The Creeping Garden makes heavy use of narration. Throughout, The Creeping Garden makes consistent use of time-lapse and macro photography, the film often cutting to this footage symbolically (for example, to demonstrate the notion given by some of the interviewees that the movement of slime moulds may be compared to the movement within groups of people). The constant cutting away to shots of slime moulds, accompanied by the eerie electronic music which alludes to the paradigms of 1970s science fiction films about nature gone amok (eg, Saul Bass’ Phase IV, 1974), makes The Creeping Garden feel strongly like a documentary in the poetic mode. The overall effect is of a documentary which emphasises rhythmic, lyrical qualities, creating association between its subject (slime moulds) and related topics (computer circuitry; road networks; the movement of groups of people) through its editing – not dissimilar to Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982). However, where The Creeping Garden differs from Koyaanisqatsi is in The Creeping Garden’s use of narration: where Koyaanisqatsi avoided a guiding human voice, The Creeping Garden makes heavy use of narration.

The Creeping Garden has no single guiding voice but instead features narration by the various participants. Principally, the film contrasts voices of professional scientists (Bryn), artists (Heather), and amateur naturalists (Mark). However, these points of narration are never really ‘expository’; the voices of the commentators never overlap but collide in their meaning, suggesting that the focus of the film is, at least in part, as much on the participants’ fascination with slime moulds, and what they represent to them, as with the slime moulds themselves. (‘What I’m interested in is that line between seduction and repulsion’, Heather tells us at one point; towards the end of the film, experimental musician Eduardo Miranda states that his interest in slime moulds revolves around his ability to ‘Harness the behaviour [of the slime moulds] to help me with my creativity’.) The film suggests the areas of overlap between the worlds of the artist and musician, the amateur naturalist, and the professional scientist (in various fields): at a conference, the artist Heather stages an experiment in which she tethers volunteers together and asks them to move towards a simulated food source (a picture of an oat) as if they were a slime mould. The overlap between these worlds is consolidated when we see Heather out in the woods, Mark’s territory, photographing and capturing examples of slime moulds – it is an activity that, Heather freely admits, represents the first time she has attempted to engage with slime moulds in their natural habitat (something which Mark does as a matter of course).

There are a number of points of disagreement amongst the various commentators, which become more apparent as the documentary moves towards its conclusion. Chief among these is the issue of whether slime moulds may be considered to have some form of ‘intelligence’ (in terms of their seeming ability to seek out food sources or to react to negative stimuli) or that their movement may be considered to be a form of ‘behaviour’. Certainly, at the core of the film is the debate as to whether slime moulds may be considered animal (owing to what the artist Heather Barnett – against what is said by the scientists, amateur or otherwise – suggests is the organism’s primitive ‘intelligence’), simply fungi (owing to the fact that they reproduce via spores), or something else entirely. Bryn subtly corrects Heather’s assertion that slime moulds are ‘intelligent’ beings by arguing that slime mould exhibits ‘mechanistic responses to external stimuli’ – but not anything that can be considered ‘behaviour’ in the true sense of the word. Mark suggests that the slime moulds can’t be considered fungi as ‘Fungus don’t [sic] move. Slime moulds do move. The only thing they have in common is they reproduce as spores’; Mark continues by asserting that ‘They’re not animal, not vegetable, not fungus’. The documentary doesn’t look down upon the work of the amateur naturalist (Mark) but instead reminds us, explicitly, of the origins of the word amateur (ie, someone who pursues a topic or area of interest out of pure love for it) and the importance of amateurs in furthering our understanding of the world, art and technology (eg, via the work of amateur naturalists and filmmakers such as F Percy Smith). As Tim reminds us, amateur scientists ‘do the work because they love it, not because they’re second-rate but because they must do it’. There are a number of points of disagreement amongst the various commentators, which become more apparent as the documentary moves towards its conclusion. Chief among these is the issue of whether slime moulds may be considered to have some form of ‘intelligence’ (in terms of their seeming ability to seek out food sources or to react to negative stimuli) or that their movement may be considered to be a form of ‘behaviour’. Certainly, at the core of the film is the debate as to whether slime moulds may be considered animal (owing to what the artist Heather Barnett – against what is said by the scientists, amateur or otherwise – suggests is the organism’s primitive ‘intelligence’), simply fungi (owing to the fact that they reproduce via spores), or something else entirely. Bryn subtly corrects Heather’s assertion that slime moulds are ‘intelligent’ beings by arguing that slime mould exhibits ‘mechanistic responses to external stimuli’ – but not anything that can be considered ‘behaviour’ in the true sense of the word. Mark suggests that the slime moulds can’t be considered fungi as ‘Fungus don’t [sic] move. Slime moulds do move. The only thing they have in common is they reproduce as spores’; Mark continues by asserting that ‘They’re not animal, not vegetable, not fungus’. The documentary doesn’t look down upon the work of the amateur naturalist (Mark) but instead reminds us, explicitly, of the origins of the word amateur (ie, someone who pursues a topic or area of interest out of pure love for it) and the importance of amateurs in furthering our understanding of the world, art and technology (eg, via the work of amateur naturalists and filmmakers such as F Percy Smith). As Tim reminds us, amateur scientists ‘do the work because they love it, not because they’re second-rate but because they must do it’.

Video

The film is complete and runs for 84:04 mins. Shot digitally, The Creeping Garden fills approximately 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in the 2.35:1 ratio, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The image has a crispness and vibrancy to it, the woodland footage dominated by lush greens and the slime moulds blooming with vibrant yellows. Contrast levels are good (if flattened slightly by the more contracted dynamic range of the digital sensors on which the film was shot, as compared with 35mm film); there is good shadow detail and defined midtones. It's an excellent presentation of a digital source. The film is complete and runs for 84:04 mins. Shot digitally, The Creeping Garden fills approximately 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in the 2.35:1 ratio, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The image has a crispness and vibrancy to it, the woodland footage dominated by lush greens and the slime moulds blooming with vibrant yellows. Contrast levels are good (if flattened slightly by the more contracted dynamic range of the digital sensors on which the film was shot, as compared with 35mm film); there is good shadow detail and defined midtones. It's an excellent presentation of a digital source.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is rich and fills the soundscape with otherworldly pulsing sounds and strange, ethereal music. Dialogue is clear and audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

Alongside the main feature, the disc includes: Alongside the main feature, the disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Tim Grabham and Jasper Sharp. In this animated commentary track, Grabham and Sharp discuss the origins of the production and how they went about obtaining some of the stock footage (for example, the NBC news broadcast with which the film opens). They talk about the appeal of the subject matter and the difficulties in obtaining footage of the slime moulds moving. There’s some fascinating coverage of the film’s photography and sound design, in particular.

- ‘Biocomputer Music’ (6:06). This short film by Tim Grabham focuses on the work of experimental musician Eduardo Miranda and his colleague Ed Braund, who working together built the first biocomputer music system. Miranda and Braund explain their work here.

- ‘Return to the Fungarium’ (3:03). In this featurette, Bryn Dentinger takes the viewer on a tour of Kew Gardens’ Fungarium.

- ‘Feeding Habits of Physarum’ (2:19). Andrew Adamatzky discusses the feeding habits of slime moulds. This interview is accompanied by optional English subtitles, owing to the fact that Adamatzky’s accent is quite strong.

- ‘cinema iloobia Short Films’:

o ‘Milk’ (1:12). Directed by Tim Grabham in 2009, this short film offers what seems like a dry run for The Creeping Garden, making use of macro photography, reverse photography, slow-motion/time-lapse photography and experimental sound design to show milk dropping in to a glass of oil in a way that makes the imagery seem strangely alien and ethereal.

o ‘Rotten’ (1:16). Another short film by Tim Grabham, made in 2012 ‘Rotten’ was shot with a macro lens on a handheld microscope. The subject is a snail; the raw footage was recorded on VHS before being digitised, again with the result of making a common object (the snail) appear alien and obscene.

o ‘Paramusical Ensemble’ (9:43). In 2015, Grabham made this short film which follows Eduardo Miranda and Joel Eaton at the Royal Hospital for Neurodisability, where they employed their Brain-Computer Music Interface to enable severely motor-impaired subjects to make music.

- ‘Angela Mele’s Animated Slime Moulds’ (2:48). Here, the viewer is presented with a text-less version of biological illustrator Angele Mele’s animated end credits sequence for the film.

- Gallery (0:45). This gallery contains promotional material for the film and some stills from its production.

- US Theatrical Trailer (0:35).

Also included in the package is a CD containing the music composed for the film by Jim O’Rourke. This is an excellent inclusion; the music sounds like the score for a lost and forgotten 1970s science fiction picture. The compositions are otherworldly and haunting.

Retail versions include an illustrated booklet containing writing about the film by Jasper Sharp.

Overall

A beautifully-assembled documentary, The Creeping Garden seems as much about human responses to slime moulds – from F Percy Smith’s use of ‘time magnification’ to capture their growth, to Miranda’s reflections on how he harnesses the ‘behaviour’ of slime moulds ‘to help my creativity’ – as it is about myxomycetes themselves. A beautifully-assembled documentary, The Creeping Garden seems as much about human responses to slime moulds – from F Percy Smith’s use of ‘time magnification’ to capture their growth, to Miranda’s reflections on how he harnesses the ‘behaviour’ of slime moulds ‘to help my creativity’ – as it is about myxomycetes themselves.

It’s a strange documentary, and its poetic/abstract qualities might remind the viewer of documentaries such as Koyaanisqatsi or those of Werner Herzog. In its sense of an unseen world that exists amongst us, highlighted by Mark and Heather’s hunting for these strange organisms in the woods, and in the film’s references to the paradigms of science-fiction cinema within its photography and sound design, the viewer might be reminded of the work of J G Ballard; in fact, the idea of bourgeois enthusiasts of slime moulds foraging through the woods on weekends, photographing and collecting these organisms in order to use their oscillations for artworks and musical compositions, sounds like it might be the plot outline of a lost novel by J G Ballard.

Shot digitally, the film is presented with integrity on this digital home video release. The Creeping Garden is also accompanied by some excellent contextual material, and the inclusion of a CD containing Jim O’Rourke’s music for the picture is an excellent idea.

References:

Sharp, Jasper, 2016: ‘The Creeping Garden: Articulating the Science of Slime Mould on Film’. In: Adamatzy, Andrew (ed), 2016: Advances in Physarum Machines: Sensing and Computing with Slime Mould. Springer: 789-801

> >

|