|

|

The Film

Caltiki, the Immortal Monster (Riccardo Freda, 1959) Caltiki, the Immortal Monster (Riccardo Freda, 1959)

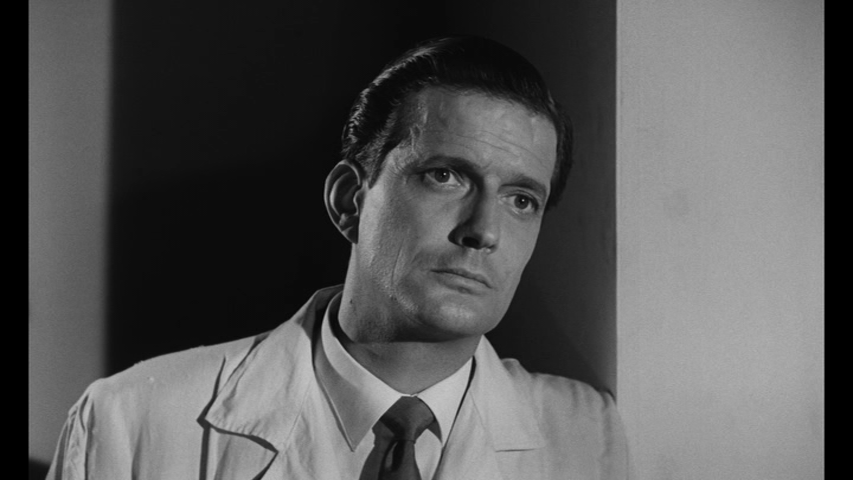

At an archaeological expedition to the ancient Mayan city of Tikal, where in 607AD the population ‘emigrated en masse towards the distant wild north’ (in the words of the extradiegetic narrator who opens the film) in fear of an apocalyptic prophecy regarding the ‘bloodthirsty’ goddess Caltiki, one of the archaeologists, Nieto (Arturo Dominici), returns to camp and collapses. His companion, Ulmer, is missing, and Nieto is unable to speak coherently, being able to mutter only the words ‘Ulmer… The mummy… Caltiki!’ Showing concern for Nieto are fellow archaeologists John (John Merivale), Bob (Daniele Vargas) and Max (Gerard Herter), and John’s wife Ellen (Didi Sullivan) and Max’s lover Linda (Daniele Roca). The male members of the expedition return to the site of the ancent city and discover an entrance to a cave, uncovered by the recent eruption of a nearby volcano; the cave leads to an underground Mayan temple to Caltiki. Within the temple is a deep lake used for sacrifices to Caltiki; the victims of such sacrifices would be adorned with golden jewellery before being drowned in the lake. The archaeologists retrieve Ulmer’s 8mm cine-camera and vow to return to the lake with diving gear. After reviewing the footage shot by Ulmer, the archaeologists retire for the night. Despite his attachment to Linda, Max shows an erotic fascination for Ellen, who rejects his advances. In the morning, the group return to the temple and Bob dives into the lake, discovering skeletons littering the floor. He also discovers ‘treasure’ – golden necklaces which, Max says, would have been placed on those chosen to be sacrificed to Caltiki. However, Bob is attacked by something in the lake – an amorphous creature. The creature emerges from the water and attacks Max, fixing itself to his arm. John saves Max by using an axe to hack Max’s arm free from the organism – but Max’s arm is still encased in the organism.  The men flee from the creature; at a hospital, Max’s arm is freed by surgeons, but the skin beneath it is dessicated and the arm seems to have been mummified. Studying the creature, John concludes that it is a ‘unicellular being […] a revolution in the field of biology’. Carbon dating suggests that the creature is over twenty million years old. The men flee from the creature; at a hospital, Max’s arm is freed by surgeons, but the skin beneath it is dessicated and the arm seems to have been mummified. Studying the creature, John concludes that it is a ‘unicellular being […] a revolution in the field of biology’. Carbon dating suggests that the creature is over twenty million years old.

As Max recovers in hospital, he becomes increasingly cruel and bitter, telling Linda ‘They’ll pay for this now, you’ll see. I’ve been ill and suffered, but now I am strong’. It seems that the creature has released a poison into Max’s bloodstream which is infecting his brain. Meanwhile, John continues to study the organism, discovering that when exposed to radiation, it pulses and grows; John speculates that if the organism is exposed to enough radiation, it may even be able to reproduce itself. Max becomes more aggressive and spiteful, and escapes from the hospital after killing a nurse. He makes his way to the home of John and Ellen, motivated by his erotic fascination with John’s wife; aided and abetted by Linda, Max sneaks into the cellar of John and Ellen’s home, threatening their lives and the life of their young child Jenny. Meanwhile, John becomes cognisant of the Mayan prophecy regarding Caltiki, which declares that the world will end when Caltiki’s bridegroom arrives; John believes this to refer to a comet which passes by the Earth’s orbit once every 3200 years – and this comet is due to pass by the Earth very soon.  The film begins with extradiegetic narration, in which we are told the story of ‘the ancient city of Tikal, 300 miles south of Mexico City’, from which – in 607AD – the population ‘emigrated […] towards the distant, wild north’. The migration can not be rationalised, and the narrator tells us that the nomadic Indians who travel across the land speak of how their ancestors fled the city to escape the wrath of a terrible goddess […]: Caltiki’. This part of the story is rooted in some element of fact: the once powerful city of Tikal, in Guatemala, was abandoned by the 10th Century, though the reason for this is much more mundane than the explanation given in the film, owing simply to a decline in the Mayan culture generally. However, the idea of an abandoned settlement is something that resonates throughout history: for example, in the story of the ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke Island. The film begins with extradiegetic narration, in which we are told the story of ‘the ancient city of Tikal, 300 miles south of Mexico City’, from which – in 607AD – the population ‘emigrated […] towards the distant, wild north’. The migration can not be rationalised, and the narrator tells us that the nomadic Indians who travel across the land speak of how their ancestors fled the city to escape the wrath of a terrible goddess […]: Caltiki’. This part of the story is rooted in some element of fact: the once powerful city of Tikal, in Guatemala, was abandoned by the 10th Century, though the reason for this is much more mundane than the explanation given in the film, owing simply to a decline in the Mayan culture generally. However, the idea of an abandoned settlement is something that resonates throughout history: for example, in the story of the ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke Island.

Heavily indebted to Val Guest’s film adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s first Quatermass serial, The Quatermass Xperiment (1954), Riccardo Freda’s Caltiki, il mostro immortale (Caltiki, the Immortal Monster, 1959) was one of the pictures that cemented the form of Italian Gothic cinema that would become increasingly popular during the 1960s, via the work of filmmakers like Mario Bava (who contributed the effects work on Caltiki, also photographing and reputedly assisting in the directing of the picture, as well as collaborating with his friend Freda on a number of other projects) and Antonio Margheriti. A year later, the paradigms of Italian Gothic cinema would be further consolidated in Bava’s La maschera del demonio (Mask of Satan/Black Sunday, 1960). Outside Italy, the work of Freda, Bava and Margheriti was valourised in publications such as Alan Frank’s Horror Movies (1977) and The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror (1988), those cornerstones of any horror film fan during the 1970s and 1980s. However, where Bava’s work has been for the most part exceptionally well-represented on DVD and more recently Blu-ray, the films of Freda (and to a lesser extent Margheriti) have been somewhat sidelined during the era of digital home video, often being tied up in legal knots which prevented (and in some cases, continue to prevent) their release on DVD/Blu-ray. (Freda’s L’orribile segreto del Dr Hichcock/The Terror of Dr Hichcock, 1962, is a notable ‘classic’ of Italian Gothic cinema that for a long time was unavailable on DVD, the film only fairly recently finding a DVD/Blu-ray release – frustratingly in its abbreviated and dubbed US cinema edit – in America via Olive Films.)  Like many similar fims, Caltiki is often cited as a loose attempt at capturing the spirit of H P Lovecraft’s novels and short stories, with Charles P Mitchell in The Complete H P Lovecraft Filmography stating that Caltiki’s ‘debt to Lovecraft is enormous’ and ‘numerous scenes in the film seem like direct depictions of scenes from [Lovecraft’s story] The Call of Cthulhu’ (Mitchell, 2001: 44). Like Cthulhu, Caltiki’s name begins with a ‘C’ and is seven letters in length, and the discovery of Caltiki in its long-buried temple recalls the line in the Lovecraft story, ‘In his house at R’lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming’ (ibid.). Both Cthulhu and Caltiki rise out of water and are ‘depicted in terrible stone bas-reliefs’; both are also ‘gelatinous, yet retain […] a standard form’, and they are ‘ancient and ageless, in essence a deity’ (ibid.). Whether Mitchell is stretching the point or his analysis of Caltiki is founded in ‘confirmation bias’ is a matter of opinion, but certainly – whether intentional or not – Caltiki has elements within it that echo some of the themes of Lovecraft’s fiction. Like many similar fims, Caltiki is often cited as a loose attempt at capturing the spirit of H P Lovecraft’s novels and short stories, with Charles P Mitchell in The Complete H P Lovecraft Filmography stating that Caltiki’s ‘debt to Lovecraft is enormous’ and ‘numerous scenes in the film seem like direct depictions of scenes from [Lovecraft’s story] The Call of Cthulhu’ (Mitchell, 2001: 44). Like Cthulhu, Caltiki’s name begins with a ‘C’ and is seven letters in length, and the discovery of Caltiki in its long-buried temple recalls the line in the Lovecraft story, ‘In his house at R’lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming’ (ibid.). Both Cthulhu and Caltiki rise out of water and are ‘depicted in terrible stone bas-reliefs’; both are also ‘gelatinous, yet retain […] a standard form’, and they are ‘ancient and ageless, in essence a deity’ (ibid.). Whether Mitchell is stretching the point or his analysis of Caltiki is founded in ‘confirmation bias’ is a matter of opinion, but certainly – whether intentional or not – Caltiki has elements within it that echo some of the themes of Lovecraft’s fiction.

Shucking off the focus on space and scientific ‘mumbo jumbo’ that characterised contemporaneous Italian SF pictures such as Paolo Heusch’s La morte viene dallo spazio/The Day the Sky Exploded (1958) in favour of Gothic suggestion and horror, Caltiki was Freda’s second attempt at making a Gothic horror film in Italy, following I vampiri (The Vampires/The Devil’s Commandment, 1957). I vampiri wasn’t the commercial success it was hope to be, so with Caltiki the filmmakers attempted to catch a broader audience (both domestically and internationally) by Anglicising their names, allowing Caltiki to be sold in Italy as if it were an American import. (Sergio Leone and his crew would adopt a similar tactic, to incredible success, when they made Per un pugno di dollari/A Fistful of Dollars in 1964.) To this end, the film strives to appear as much like a British or American SF/horror picture as possible.  The film conforms to some of the paradigms of American films of the era. Notably, like many American Westerns of the 1950s (such as Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon, 1953), Caltiki juxtaposes two types of femininity: the earthy, sensual and superstitious ‘half breed’ (as her lover Max describes her) Linda, and the rational, whitebread Caucasian housewife Ellen. The manner in which the film contrasts the two women is very similar to the contrast established between Grace Kelly and Katy Jurado in High Noon. From very early in the film, Linda demonstrates a strong sense of superstition, asserting when Nieto returns to the camp that ‘We shouldn’t have come here, and [in doing so] we’ve provoked evil spirits’. In a moment that speaks of an attempt to capture the ‘exotic’ nature of the setting, during the night that passes before the group return to the temple with diving equipment, the archaeologists listen to a group of locals as they beat out a primal rhythm on drums; evidencing a familiarity with the indigenous culture that bypasses the other members of the expedition, Linda asserts that this rhythm is ‘a spell to placate the anger of the evil spirits’. Bob sneaks up on this group of locals, shooting photographs with a Rolleiflex whilst a local girl dances furiously to the beat of the drums; it’s a stereotypically ‘exotic’ display of primal music and superstition, all wrapped up with a bow of subtle eroticism, that is familiar from any number of horror films set in ‘distant’ environments, including Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie (1943): the Caucasian explore watches the local people enacting an ancient and mysterious rite. (Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2, 1979, features a similar connection between ‘tribal’ drums and the appearance of the film’s monsters, the zombies which may or may not have been resurrected by Voodoo practices; and Joe D’Amato’s Black Emanuelle films include numerous similar scenarios.) The moment comes to an end when the dancing girl notices Bob photographing her with his Rolleiflex whilst hiding in the bushes, and she screams, alerting the others. The film conforms to some of the paradigms of American films of the era. Notably, like many American Westerns of the 1950s (such as Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon, 1953), Caltiki juxtaposes two types of femininity: the earthy, sensual and superstitious ‘half breed’ (as her lover Max describes her) Linda, and the rational, whitebread Caucasian housewife Ellen. The manner in which the film contrasts the two women is very similar to the contrast established between Grace Kelly and Katy Jurado in High Noon. From very early in the film, Linda demonstrates a strong sense of superstition, asserting when Nieto returns to the camp that ‘We shouldn’t have come here, and [in doing so] we’ve provoked evil spirits’. In a moment that speaks of an attempt to capture the ‘exotic’ nature of the setting, during the night that passes before the group return to the temple with diving equipment, the archaeologists listen to a group of locals as they beat out a primal rhythm on drums; evidencing a familiarity with the indigenous culture that bypasses the other members of the expedition, Linda asserts that this rhythm is ‘a spell to placate the anger of the evil spirits’. Bob sneaks up on this group of locals, shooting photographs with a Rolleiflex whilst a local girl dances furiously to the beat of the drums; it’s a stereotypically ‘exotic’ display of primal music and superstition, all wrapped up with a bow of subtle eroticism, that is familiar from any number of horror films set in ‘distant’ environments, including Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie (1943): the Caucasian explore watches the local people enacting an ancient and mysterious rite. (Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2, 1979, features a similar connection between ‘tribal’ drums and the appearance of the film’s monsters, the zombies which may or may not have been resurrected by Voodoo practices; and Joe D’Amato’s Black Emanuelle films include numerous similar scenarios.) The moment comes to an end when the dancing girl notices Bob photographing her with his Rolleiflex whilst hiding in the bushes, and she screams, alerting the others.

Max approaches Ellen sleazily, asserting ‘You’re a very sensitive creature, You need warmth and affection […] I hope one day you’ll seek refuge in my arms’. Following Ellen’s rejection of his advances, Max cruelly criticises Linda, asserting that he ‘rescued’ her from ‘a third-rate joint’. When Linda reminds Max that he promised to stand by her, Max tells her ‘You promise all sorts to a girl like you; and anyway, I’m sure I wasn’t the first’. ‘If you’re trying to tell me you’re looking for a husband’, Max continues, ‘take me off the list. Find yourself a half breed; someone like you’. However, despite his cruel treatment of her, when Max is hospitalised following his encounter with Caltiki, Linda sticks with him, helping him whilst he hides in the cellar of John and Ellen’s home Max approaches Ellen sleazily, asserting ‘You’re a very sensitive creature, You need warmth and affection […] I hope one day you’ll seek refuge in my arms’. Following Ellen’s rejection of his advances, Max cruelly criticises Linda, asserting that he ‘rescued’ her from ‘a third-rate joint’. When Linda reminds Max that he promised to stand by her, Max tells her ‘You promise all sorts to a girl like you; and anyway, I’m sure I wasn’t the first’. ‘If you’re trying to tell me you’re looking for a husband’, Max continues, ‘take me off the list. Find yourself a half breed; someone like you’. However, despite his cruel treatment of her, when Max is hospitalised following his encounter with Caltiki, Linda sticks with him, helping him whilst he hides in the cellar of John and Ellen’s home

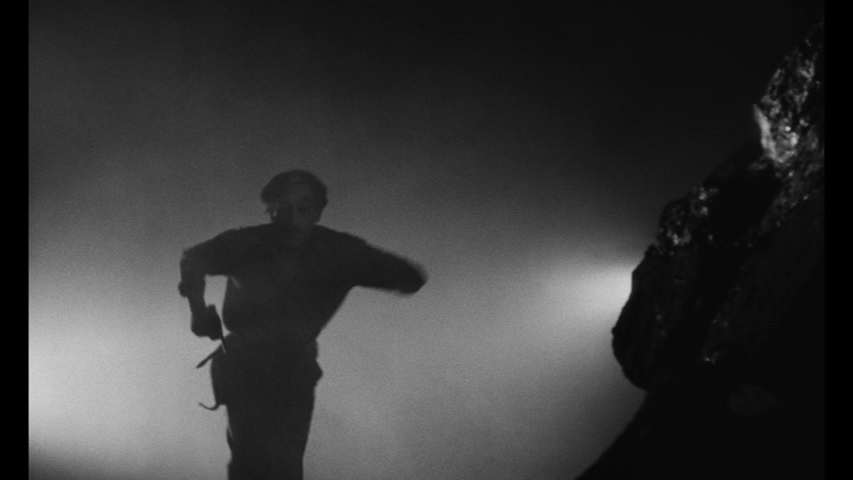

The film features a number of bravura setpieces. The sequence in which the team watch the silent footage shot on Ulmer’s 8mm cine-camera, which shows Ulmer and Nieto descending into the underground temple before being attacked by an unseen entity, is strikingly effective. It seems to draw upon the similar use of ‘found’ footage in The Quatermass Xperiment (the silent footage of the astronauts in their capsule) and is very similar to the eerie videotapes that the American scientists discover at the Norwegian camp in John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing (1982), which show the Norwegian expedition using thermite charges to uncover an alien spaceship buried in the snow and ice. Caltiki’s other most impressive sequence features Bob diving to the floor of the lake in the underground temple, discovering the skeletal remains of those sacrificed to Caltiki on the floor of the lake. To some extent, the sequence recalls the pioneering visual effects used to capture Ahmed’s (Douglas Fairbanks) journey to the sea floor in Raoul Walsh’s The Thief of Baghdad (1924).  In the film’s realisation of its amorphous monster (‘man-eating protoplasm’, as it is described in the film’s trailer), Caltiki has some similarities, incidental or not, with The Blob (Irvin Yeaworth, 1958), and in fact one of Caltiki’s most memorable effects sequences (in which the alien creature ‘absorbs’ a man and ‘regurgitates’ his skull) seems to have found its way into the much more graphic 1988 remake of The Blob (directed by Chuck Russell), as does the idea of the organism ‘capturing’ its first victim’s hand and devouring it whilst this victim is still alive. However, Caltiki is remarkably different from many of the American SF/horror pictures that were popular in the late-1950s, emblematised by The Blob: where The Blob was in vivid colour, Caltiki was shot in monochrome. The Blob’s focus on small town America, its fast pace and its cast of young actors (including Steve McQueen) is in contrast with Caltiki’s setting amidst ancient Mayan ruins, its sedate (almost funereal) narrative progression and the story’s focus on a team of middle-aged archaeologists. In this sense, Caltiki betrays the influence of the SF/horror pictures that Hammer made in the 1950s –such as The Quatermass Xperiment and The Abominable Snowman (Val Guest, 1957) – prior to the popularity of the studio’s colour Gothics (beginning with Terence Fisher’s The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957). In the film’s realisation of its amorphous monster (‘man-eating protoplasm’, as it is described in the film’s trailer), Caltiki has some similarities, incidental or not, with The Blob (Irvin Yeaworth, 1958), and in fact one of Caltiki’s most memorable effects sequences (in which the alien creature ‘absorbs’ a man and ‘regurgitates’ his skull) seems to have found its way into the much more graphic 1988 remake of The Blob (directed by Chuck Russell), as does the idea of the organism ‘capturing’ its first victim’s hand and devouring it whilst this victim is still alive. However, Caltiki is remarkably different from many of the American SF/horror pictures that were popular in the late-1950s, emblematised by The Blob: where The Blob was in vivid colour, Caltiki was shot in monochrome. The Blob’s focus on small town America, its fast pace and its cast of young actors (including Steve McQueen) is in contrast with Caltiki’s setting amidst ancient Mayan ruins, its sedate (almost funereal) narrative progression and the story’s focus on a team of middle-aged archaeologists. In this sense, Caltiki betrays the influence of the SF/horror pictures that Hammer made in the 1950s –such as The Quatermass Xperiment and The Abominable Snowman (Val Guest, 1957) – prior to the popularity of the studio’s colour Gothics (beginning with Terence Fisher’s The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957).

Following Luigi Cozzi’s 1971 interview with Riccardo Freda, published in Photon, rumours have persisted that Bava was the uncredited director of at least part of Caltiki. In the interview with Cozzi, Freda suggested that he made Caltiki ‘just to help [Mario] Bava’, who at that stage in his career was directing various pictures in an uncredited capacity whilst also being ‘humiliated’ by Pietro Francisci – for whom Bava photographed and designed/lensed special effects sequences frequently (Freda, quoted in Curti, 2017: 143). Freda proposed Caltiki as a way of getting work for Bava away from Francisci, and asserted that he left the set with ‘just two days of shooting left’, leaving the project in Bava’s hands as a way of attempting to push his friend into directing: ‘I did shoot it, yes, but it was Bava’s type of film’, Freda said (Freda, quoted in ibid.). However, in 2004 Cozzi offered a riposte to the bold claims that Bava ‘directed’ Caltiki, suggesting that ‘over thirty years ago it was I who first hinted at this story, and many have reprised my words, misinterpreting them’ (Cozzi, quoted in ibid.). The ‘truth’, however, ‘is only one’: Freda directed the film and Bava photographed it, organising the special effects and the miniature shots (Cozzi, quoted in ibid.). ‘That’s all’, Cozzi asserted, ‘and of course it cannot be enough to say that Bava directed that movie’ (Cozzi, quoted in ibid.). Cozzi quoted an interview he conducted with Bava, who declared ‘I did not direct Caltiki. The director of that movie is Freda’, and recollected that after the film had been shot Freda had a disagreement with the producer over the editing of the picture: ‘Freda walked out, slamming the door, and did not take care of the movie any longer’ (Bava, quoted in ibid.). Some scenes were ‘left to be filmed—some special effects, the scenes of the soldiers with the flame throwers for the ending, the miniatures of the house and the tanks’; Bava ‘shot those myself’, but this was only ‘part of my job as cameraman as well as second unit director’ (Bava, quoted in ibid.). However, other sources, including Tim Lucas’ book about Bava, suggest that Bava’s involvement in the directing of the film was significantly larger (Lucas suggests two or three weeks’ worth of shooting was left for Bava to complete); Massimo De Rita, the film’s writer, meanwhile suggested that Bava was director of Caltiki ‘at 90 percent’, shooting ‘over 50 percent of the scenes featuring actors’ (Lucas, cited in ibid.; De Rita, quoted in ibid.: 144). Following Luigi Cozzi’s 1971 interview with Riccardo Freda, published in Photon, rumours have persisted that Bava was the uncredited director of at least part of Caltiki. In the interview with Cozzi, Freda suggested that he made Caltiki ‘just to help [Mario] Bava’, who at that stage in his career was directing various pictures in an uncredited capacity whilst also being ‘humiliated’ by Pietro Francisci – for whom Bava photographed and designed/lensed special effects sequences frequently (Freda, quoted in Curti, 2017: 143). Freda proposed Caltiki as a way of getting work for Bava away from Francisci, and asserted that he left the set with ‘just two days of shooting left’, leaving the project in Bava’s hands as a way of attempting to push his friend into directing: ‘I did shoot it, yes, but it was Bava’s type of film’, Freda said (Freda, quoted in ibid.). However, in 2004 Cozzi offered a riposte to the bold claims that Bava ‘directed’ Caltiki, suggesting that ‘over thirty years ago it was I who first hinted at this story, and many have reprised my words, misinterpreting them’ (Cozzi, quoted in ibid.). The ‘truth’, however, ‘is only one’: Freda directed the film and Bava photographed it, organising the special effects and the miniature shots (Cozzi, quoted in ibid.). ‘That’s all’, Cozzi asserted, ‘and of course it cannot be enough to say that Bava directed that movie’ (Cozzi, quoted in ibid.). Cozzi quoted an interview he conducted with Bava, who declared ‘I did not direct Caltiki. The director of that movie is Freda’, and recollected that after the film had been shot Freda had a disagreement with the producer over the editing of the picture: ‘Freda walked out, slamming the door, and did not take care of the movie any longer’ (Bava, quoted in ibid.). Some scenes were ‘left to be filmed—some special effects, the scenes of the soldiers with the flame throwers for the ending, the miniatures of the house and the tanks’; Bava ‘shot those myself’, but this was only ‘part of my job as cameraman as well as second unit director’ (Bava, quoted in ibid.). However, other sources, including Tim Lucas’ book about Bava, suggest that Bava’s involvement in the directing of the film was significantly larger (Lucas suggests two or three weeks’ worth of shooting was left for Bava to complete); Massimo De Rita, the film’s writer, meanwhile suggested that Bava was director of Caltiki ‘at 90 percent’, shooting ‘over 50 percent of the scenes featuring actors’ (Lucas, cited in ibid.; De Rita, quoted in ibid.: 144).

Video

Please note: Only a DVD copy of the release was provided for review. Please note: Only a DVD copy of the release was provided for review.

Caltiki is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, with anamorphic enhancement on the DVD version. An alternate ‘full aperture’ presentation is included on the disc as an ‘extra’. Some of the film was shot with a hard matte, whilst other sequences (including the effects shots) were filmed with a soft matte; as stated in the onscreen title that accompanies this alternate presentation of the main feature the intention with the ‘full aperture’ presentation is to allow the viewer to experience the effects shots, in particular, sans the matte. (Arguably, this alternate presentation is slightly redundant; open matte presentations of the effects shots could perhaps have been presented separate from the main feature, within the ‘Extra Features’ menu. Nevertheless, regardless of how redundant one may consider this alternate presentation to be, it represents clear ‘added value’ to the release.) The film is uncut, with a running time of 76:26 mins (NTSC). The 35mm monochrome photography fares well on this release; the image is detailed and crisp. Some notoriously difficult-to-remove vertical lines are present here and there. The level of detail is good throughout. The midtones have balance and definition to them. Much of the film takes place in low-light settings, and these fare reasonably well on the DVD we were given for review, though deeper blacks are often ‘crushed’ and shadow detail lost; whether this is true for the Blu-ray presentation is another matter entirely, however, and we can’t speak for that.

Audio

On the DVD provided for review, the viewer is offered the option of watching the film in English (with optional English HoH subtitles) or Italian (with optional subtitles translated from the Italian dialogue). Both tracks are Dolby Digital 1.0. The English and Italian dialogue is near-identical in general content, though sometimes the specificities of what is said in each version is rather different. None of the English dialogue is provided by the actors, though the English dub often matches their lip movements (especially in the case of the Canadian actor John Merivale). The English audio track is a composite from various sources and shows some wear and tear, though dialogue is always audible. The Italian track is clean and clear throughout. Subtitles are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by Tim Lucas. Lucas’ commentary track is typically dense and packed with information. The track focuses heavily on Bava’s input into the film, Lucas describing and analysing the film’s visual effects. Lucas speculates that the dark, underexposed appearance of the film was a deliberate choice on the part of Bava to ‘protect’ the film’s use of glass mattes. Lucas talks about the friendship between Freda and Bava, discussing the casting of the picture and talking about some of the relationships between the cast and crew on and off the set of the film. - An audio commentary by Troy Howarth. Troy’s commentary is equally packed with information, contextualising Caltiki within Italian ‘fantastique’ cinema generally and reflecting on the attempts by the cast and crew to convince audiences that they were watching an American or British film. He discusses the performances of the film’s cast, and discusses the picture’s influence by Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass serials. - ‘From Quatermass to Caltiki’ (18:15). In this new featurette, Kim Newman reflects on the influence on Caltiki of Nigel Kneale’s work and other science fiction pictures of the 1950s, such as Christian Nyby/Howard Hawks’ The Thing from Another World (1951). - ‘Riccardo Freda: Forgotten Master’ (19:04). Recorded for inclusion on NoShame’s DVD release of Caltiki in Italy, this featurette (actually titled ‘Il ritorno di Caltiki’, or ‘The Return of Caltiki’, onscreen) features Italian critic Stefania Della Casa talking about Caltiki’s place in the development of the Italian horror film. The featurette is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. -  ‘The Genesis of Caltiki’ (21:32). Also recorded for inclusion on NoShame’s 2007 Italian DVD release, this interview with Luigi Cozzi is presented in Italian with optional English subtitles. Cozzi comments on the film, discussing his interviews with Cozzi and Bava and commenting on the film’s place in the history of Italian genre cinema. ‘The Genesis of Caltiki’ (21:32). Also recorded for inclusion on NoShame’s 2007 Italian DVD release, this interview with Luigi Cozzi is presented in Italian with optional English subtitles. Cozzi comments on the film, discussing his interviews with Cozzi and Bava and commenting on the film’s place in the history of Italian genre cinema.

- Archival Introduction (0:20). Stefania Della Casa provides a very brief introduction to the film, in Italian with optional English subtitles. - US trailer (2:08). - US opening titles (2:24). - Full Aperture Version (76:58 NTSC). The difference in running time as compared with the main feature is owing to an onscreen title explaining the reasons for the inclusion of this alternate presentation.

Overall

Both the story and even individual sequences are incredibly familiar, from the film’s obvious model (The Quatermass Xperiment) and subsequent pictures which may or may not betray the influence of Caltiki: William Sachs’ The Incredible Melting Man (1977), for all intents and purposes a remake of The Quatermass Xperiment but with some interesting similarities to Caltiki (and released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video and reviewed by us here); Joe D’Amato’s Horrible/Absurd (1981) – whose narrative is like the final sequences of Caltiki – in which George Eastman’s radioactive monster wreaks havoc after escaping from a hospital and killing a nurse, much like Max does in this film, leading to a final confrontation within a lavish domestic space; even John Carpenter’s The Thing exhibits some interesting points of similarity with Caltiki, not least of which is the sequence in which scientists gather round to watch silent ‘found’ footage of the films’ monsters being unearthed from their respective tombs/places of hibernation, awakening an ancient evil; the nightmarish early sequence in Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980), with effects supervised by Bava, in which Irene Miracle’s character encounters a submerged room and dives into it, encountering a corpse which seems to reach out for her; and Chuck Russell’s 1988 remake of The Blob, which sees the entity devour the hand of its first victim (much as it does Max in Caltiki) and likewise features a sequence in which the monster consumes a victim, partially revealing his skull through its membranous surface. Both the story and even individual sequences are incredibly familiar, from the film’s obvious model (The Quatermass Xperiment) and subsequent pictures which may or may not betray the influence of Caltiki: William Sachs’ The Incredible Melting Man (1977), for all intents and purposes a remake of The Quatermass Xperiment but with some interesting similarities to Caltiki (and released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video and reviewed by us here); Joe D’Amato’s Horrible/Absurd (1981) – whose narrative is like the final sequences of Caltiki – in which George Eastman’s radioactive monster wreaks havoc after escaping from a hospital and killing a nurse, much like Max does in this film, leading to a final confrontation within a lavish domestic space; even John Carpenter’s The Thing exhibits some interesting points of similarity with Caltiki, not least of which is the sequence in which scientists gather round to watch silent ‘found’ footage of the films’ monsters being unearthed from their respective tombs/places of hibernation, awakening an ancient evil; the nightmarish early sequence in Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980), with effects supervised by Bava, in which Irene Miracle’s character encounters a submerged room and dives into it, encountering a corpse which seems to reach out for her; and Chuck Russell’s 1988 remake of The Blob, which sees the entity devour the hand of its first victim (much as it does Max in Caltiki) and likewise features a sequence in which the monster consumes a victim, partially revealing his skull through its membranous surface.

It’s the film’s setpieces that are memorable: the diving expedition into the sacrificial lake within Caltiki’s temple, which reveals the skeletons of victims of Mayan sacrifice and jewellery used in the rituals littering the bottom of the lake; Max’s gradual deterioration in the hospital. Caltiki is an entertaining film, and an important one in the development of Italian Gothic cinema. Arrow’s new release of the film contains a good presentation of the film alongside some very good contextual material. References Curti, Roberto, 2017: Riccardo Freda: The Life and Works of a Born Filmmaker. London: McFarland & Company Mitchell, Charles P, 2001: The Complete H P Lovecraft Filmography. London: Greenwood Publishing

|

|||||

|