|

|

Magus (The) AKA The God Game (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (30th April 2017). |

|

The Film

The Magus (Guy Green, 1968) The Magus (Guy Green, 1968)

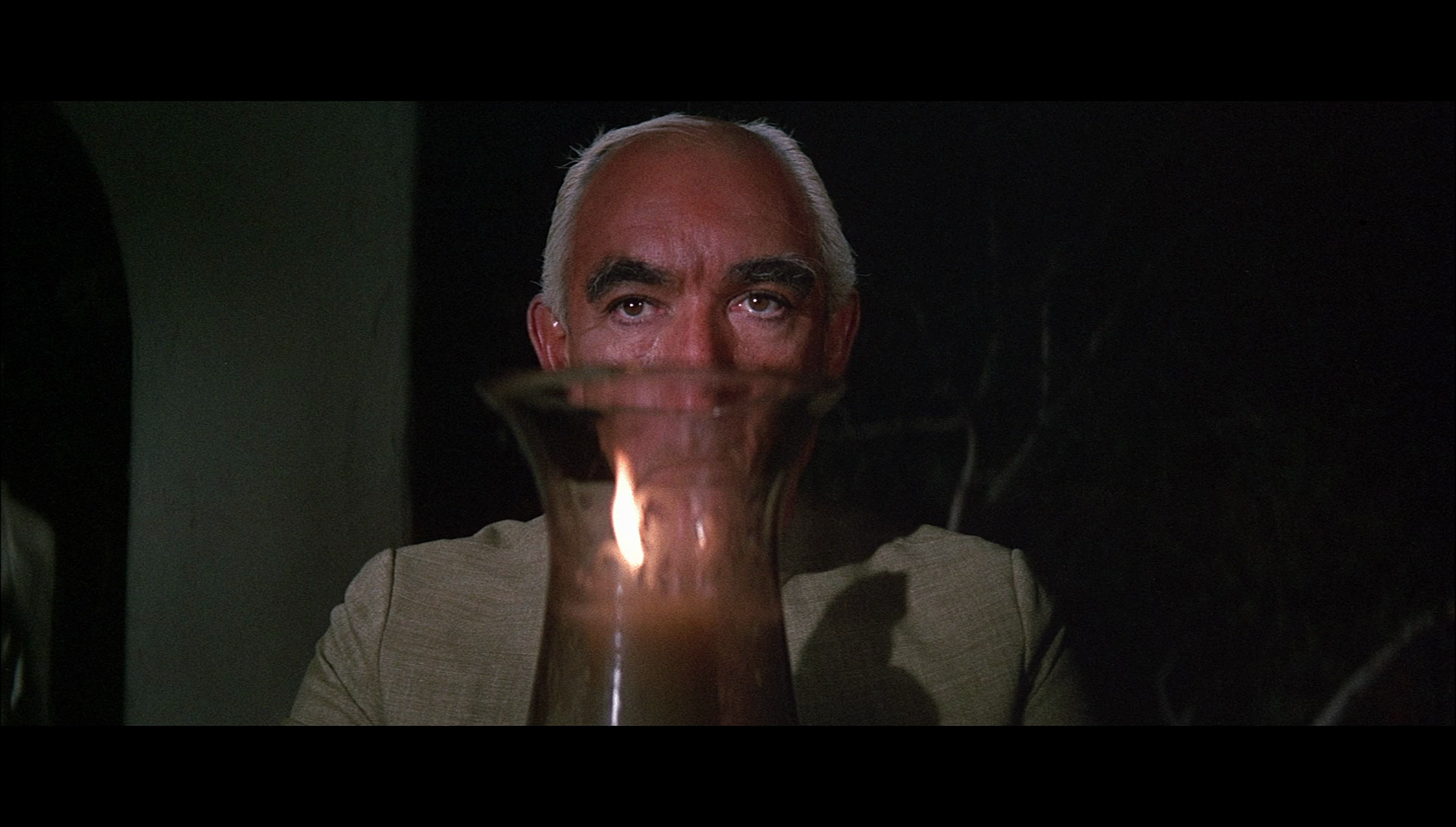

Made at a time when leading actor Michael Caine was a rising star within British (and, for that matter, world) cinema – following the successes of Zulu (Cy Endfield, 1964), Alfie (Lewis Gilbert, 1965) and The Italian Job (Peter Collinson, 1967) – and betraying the influence of the French nouvelle vague (not least through the casting of Anna Karina), Guy Green’s 1968 screen adaptation of John Fowles’ notoriously dense postmodern novel The Magus (1965) went down like a proverbial bomb upon its original release. Chief amongst its critics was its own star, Michael Caine, and infamously, in an oft-repeated wisecrack, Woody Allen once asserted that ‘If I had to live my life again, I’d do everything the same, except that I wouldn’t see The Magus’ (Allen, quoted in Sutherland, 2011: 621). In The Magus, schoolteacher Nicholas Urfe (Michael Caine) arrives on the Greek island of Phraxos to teach English at the Lord Byron school. He is met by Meli (Paul Stassino), another teacher at the same school, who tells Urfe that Urfe’s predecessor, an Englishman named Williamson, committed suicide. Via a series of flashbacks, it is revealed that Urfe has taken the job on Phraxos partly as a means of escaping his romantic relationship with pretty air hostess Anne (Anna Karina); Urfe and Anne’s relationship has soured owing to Urfe’s feelings regarding Anne’s number of sexual partners, and also Urfe’s belief that she is beneath him.  Urfe is given Williamson’s old room at the school, and in this room Urfe finds a piece of paper on which is written, cryptically, ‘The Waiting Room’. Exploring the island, Urfe discovers a sign indicating ‘The Waiting Room’. It leads to an isolated house, built on the site of a medieval chapel and filled with artworks, where Urfe encounters Maurice Conchis (Anthony Quinn). Conchis claims to be psychic and warns Urfe not to tell anyone at the school that he has met Conchis. Urfe is given Williamson’s old room at the school, and in this room Urfe finds a piece of paper on which is written, cryptically, ‘The Waiting Room’. Exploring the island, Urfe discovers a sign indicating ‘The Waiting Room’. It leads to an isolated house, built on the site of a medieval chapel and filled with artworks, where Urfe encounters Maurice Conchis (Anthony Quinn). Conchis claims to be psychic and warns Urfe not to tell anyone at the school that he has met Conchis.

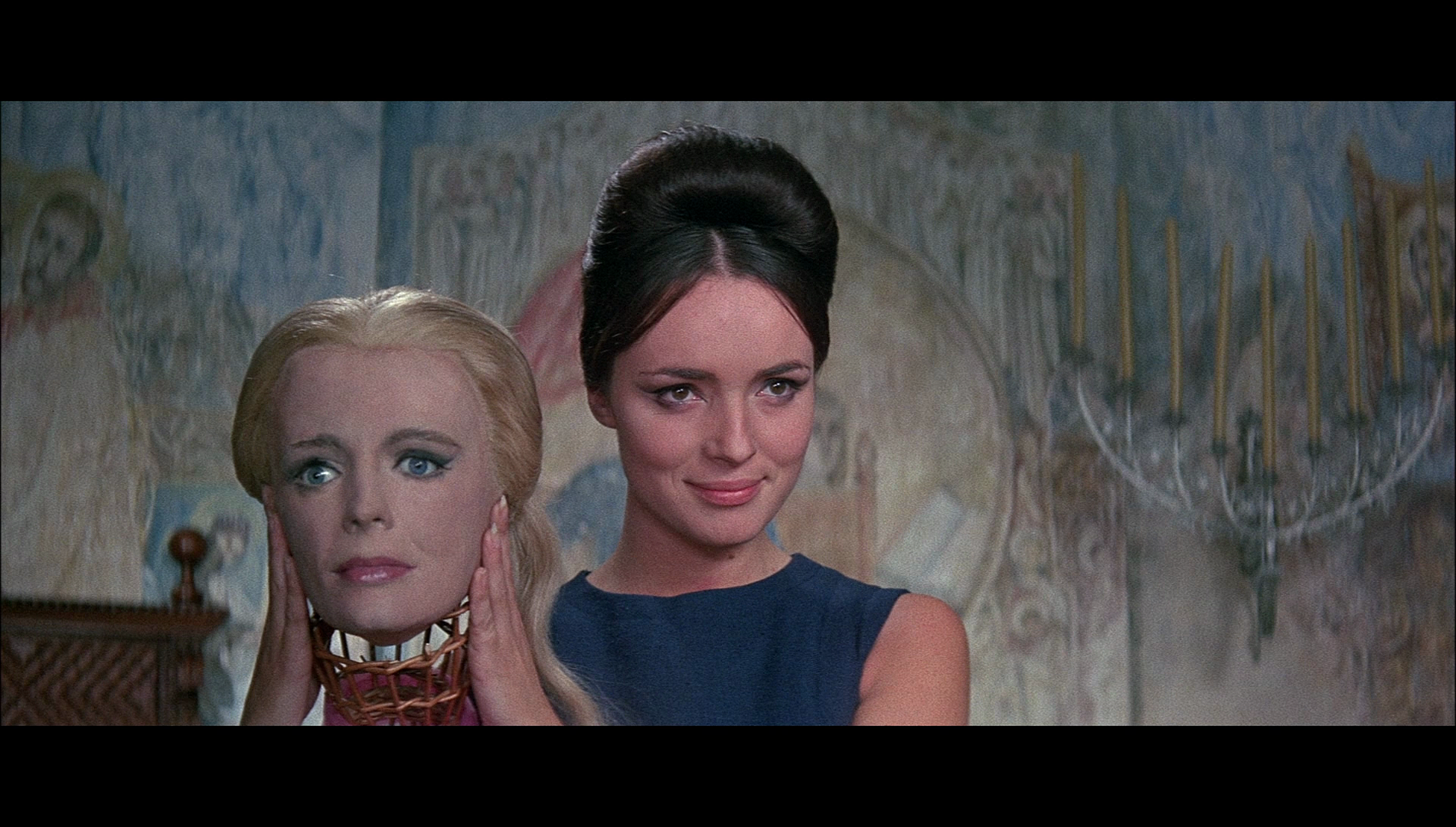

Urfe asks his acquaintances about Conchis and discovers that Conchis was said to have died a number of years previously, and rumours persist that during the Second World War, Conchis collaborated with the occupying German forces, Conchis’ actions leading to the deaths of eighty of Phraxos’ civilians. Urfe returns to Conchis’ home, and Conchis tells Urfe of his youth. Conchis was a prodigious musician and fell in love with a woman named Lily (Candice Bergen). However, when the First World War began and Conchis refused to enlist, he became alienated from Lily; Conchis’ love died in 1916 of typhoid. Whilst alone in Conchis’ home, Urfe sees a young woman; when he tells Conchis of this, Conchis suggests that Urfe has seen the ghost of Lily, and this means that Urfe is psychic too. Conchis introduces Lily to Urfe, telling Urfe that Lily is just one of the ‘visitors’ to his home. Speaking alone with Lily, Urfe draws closer to her. They kiss, before Lily wanders away and Urfe experiences a vision of her being carried off by Anubis, the Egyptian god of the dead. However, shortly afterwards Conchis tells Urfe that he (Conchis) is in fact a psychiatrist named Dr Lambros, and Lily is really a patient of his, a schizophrenic called Julie. Lily/Julie’s contact with Urfe is part of her ‘therapy’. However, when Urfe manages to speak with Lily/Julie, she pooh-poohs Conchis story, telling Urfe another: that she is an actress who has been hired to star in a film to be produced by Conchis and directed by his associate Anton (Julian Glover), and that Urfe was brought to the place as the male lead, the unwitting star of this film. Lily/Julie suggests that Urfe is under constant surveillance, and that the interactions between Lily/Julie and Urfe will form the basis for the film’s script.  Meanwhile, Anne arrives on the island; she and Urfe spend time together. However, this ends in an argument, which Anne believes is owing to Urfe’s perception of her as being promiscuous. Anne leaves, Urfe later receiving news that she has committed suicide. Urfe confronts Conchis, blaming the older man for Anne’s suicide. In response, Conchis tells Urfe the true story of what happened on the island during the Second World War: the Germans established a garrison on the island, with Conchis (reluctantly) ordered to function as the mayor of Phraxos. When partisans from the mainland attacked troops from the German garrison, the Germans responded by taking eighty civilians hostage. The partisans were captured, and the commander of the German garrison demanded that Conchis help persuade the partisans to co-operate; when they failed to do so, the German commander offered to spare the eighty civilian hostages if Conchis would execute the partisans publicly – by bludgeoning them with the stock of an MP40 submachine gun. Conchis was unable to do this, and the eighty civilians were massacred by the German troops – an action for which Conchis was blamed. Meanwhile, Anne arrives on the island; she and Urfe spend time together. However, this ends in an argument, which Anne believes is owing to Urfe’s perception of her as being promiscuous. Anne leaves, Urfe later receiving news that she has committed suicide. Urfe confronts Conchis, blaming the older man for Anne’s suicide. In response, Conchis tells Urfe the true story of what happened on the island during the Second World War: the Germans established a garrison on the island, with Conchis (reluctantly) ordered to function as the mayor of Phraxos. When partisans from the mainland attacked troops from the German garrison, the Germans responded by taking eighty civilians hostage. The partisans were captured, and the commander of the German garrison demanded that Conchis help persuade the partisans to co-operate; when they failed to do so, the German commander offered to spare the eighty civilian hostages if Conchis would execute the partisans publicly – by bludgeoning them with the stock of an MP40 submachine gun. Conchis was unable to do this, and the eighty civilians were massacred by the German troops – an action for which Conchis was blamed.

Like Fowles’ source novel, The Magus weaves a non-linear narrative in which past and present collide and sometimes blur; characters are haunted by their pasts, Conchis’ reputation as a ‘collaborationist’ dogging him, and the impact of the past upon the present is represented very directly via the film’s depiction of ‘ghosts’. On set for the production of the film, Magnum photographer Eve Arnold recollected that ‘the massacre scene of the first day’s shooting is only one of the strange evocations from the past that occur in the film’ (Arnold, op cit.: 180).  Fowles’ book is one of those ‘unfilmable’ novels: a ‘cult’ book, it features a non-linear, highly ambiguous story and numerous metafictional devices. Fowles had been unhappy with the experience of seeing his debut novel The Collector adapted for the screen (by William Wyler in 1965) and, in an attempt to ensure that The Magus was adapted in a more satisfactory manner, insisted that he wrote the screenplay for Guy Green’s film. In his journals, Fowles commented that writing the treatment for the film adaptation of The Magus was ‘a job that both bores and disgusts me’ (Fowles, quoted in Aubrey, 2015a: 5). Fowles hoped that the role of Julie would be given to Jean Shrimpton (the part was eventually played by the American actress Candice Bergen) even though Fowles acknowledged Shrimpton ‘could not act but had “cool looks” that he believed would work on screen’ (ibid.). James Aubrey has commented that ‘Fowles’s advice to cast on the basis of looks alone is a reminder of his limitations as a cinema consultant’ (ibid.). Whilst praising Anna Karina’s performance in the film, Fowles criticised Michael Caine, asserting that the actor was ‘wooden and hopelessly without depth’ (ibid.: 6). Arguments over the manner in which the film’s narrative ended also ensued, with a ‘happy ending’ being shot and included in an early assembly of the picture, against Fowles’ wishes, but being eventually removed from the film at the behest of Fox executives including Darryl F Zanuck (ibid.). The experienced embittered Fowles’ attitude towards the collaborative nature of filmmaking, Fowles asserting that ‘You cannot make good art like this’ (Fowles, quoted in ibid.). Fowles’ book is one of those ‘unfilmable’ novels: a ‘cult’ book, it features a non-linear, highly ambiguous story and numerous metafictional devices. Fowles had been unhappy with the experience of seeing his debut novel The Collector adapted for the screen (by William Wyler in 1965) and, in an attempt to ensure that The Magus was adapted in a more satisfactory manner, insisted that he wrote the screenplay for Guy Green’s film. In his journals, Fowles commented that writing the treatment for the film adaptation of The Magus was ‘a job that both bores and disgusts me’ (Fowles, quoted in Aubrey, 2015a: 5). Fowles hoped that the role of Julie would be given to Jean Shrimpton (the part was eventually played by the American actress Candice Bergen) even though Fowles acknowledged Shrimpton ‘could not act but had “cool looks” that he believed would work on screen’ (ibid.). James Aubrey has commented that ‘Fowles’s advice to cast on the basis of looks alone is a reminder of his limitations as a cinema consultant’ (ibid.). Whilst praising Anna Karina’s performance in the film, Fowles criticised Michael Caine, asserting that the actor was ‘wooden and hopelessly without depth’ (ibid.: 6). Arguments over the manner in which the film’s narrative ended also ensued, with a ‘happy ending’ being shot and included in an early assembly of the picture, against Fowles’ wishes, but being eventually removed from the film at the behest of Fox executives including Darryl F Zanuck (ibid.). The experienced embittered Fowles’ attitude towards the collaborative nature of filmmaking, Fowles asserting that ‘You cannot make good art like this’ (Fowles, quoted in ibid.).

In interview, Caine once commented that ‘I think it [the adaptation of The Magus] was almost impossible to make. They told me it would come right in the cutting room – but it didn’t. It was a contract picture, and I was told I had to do it or I would be taken to court’ (Caine, quoted in Hall, 2007: np). Making the film was reputedly an unpleasant experience for Caine, who became angered by the attitude of co-star Anthony Quinn’s entourage: ‘You get this cult thing. There was this very famous star, and he had lots of minions’ (Caine, quoted in ibid.). Quinn’s ‘right-hand man’ would announce Quinn’s mood of the day before the actor appeared on set; this wore down Caine’s patience, and one day Caine fired back ‘Just a minute, has he [Quinn] ever asked what mood I’m in?’ (Caine, quoted in ibid.). His question met with a dismissive response (‘Why should he ask what mood you’re in?’), Caine responded by questioning ‘What the fuck am I doing here?’ before leaving for ‘the next plane home’ (Caine, quoted in ibid.). He was persuaded to complete the film, however. ‘[I]t’s not a case of a personality clash’, Caine said, ‘There are people with power and money who can get enough other people running around doing their bidding for them. If you put yourself in the position of being one of the lackeys, you deserve everything you get’ (Caine, quoted in ibid.).  The film’s story, like Fowles’ novel, is structured around a very direct reference to the Madonna/Whore complex outlined by Freud. Urfe is a socially mobile creature, an academic from a working-class background: his father was a bus conductor, and Urfe gained access to university via a scholarship. At a party depicted in one of the film’s flashbacks, Urfe’s publisher describes Urfe: ‘Cracked up. Bad degree. Now classless, rootless [….] All the symptoms of contemporary genius’. Urfe’s relationship with Anne falters owing to an unstated suggestion that Urfe both sees himself as superior to Anne (in terms of education and social class), and regards her as promiscuous. When he arrives on the island of Phraxos, Urfe is told by Meli that the island has only ‘simple pleasures. Nothing to do here except swim, walk, drink ouzo. No women’. ‘Good’, Urfe responds. Upon the island, Urfe seduces Lily/Julie, after Conchis has told Urfe the story of Lily and Urfe believes her to be a product of another, more ‘innocent’ era. It’s clear that in Urfe’s mind, the ‘pure’ Lily – modest and sexually inexperienced – is contrasted with the more modern, ‘earthy’ and independent/sexually liberated Anne who, via some of the film’s flashbacks, is shown in an early encounter with Urfe confessing that she has had a significant number of sexual partners. However, as the narrative progresses Urfe realises that his idealised, innocent Lily is not who he believed her to be: her identity as Julie – perhaps a patient of Conchis’, or an actor in a film he is directing – is revealed to Urfe, and Urfe comes to an awareness that she is not a ghost from another era but rather a flesh and blood product of modern times. In the bizarre trial sequence which features as the film’s climax, the abstract sets and public call to judgement calling to mind the final episodes of Patrick McGoohan’s contemporaneous television series The Prisoner (ITC, 1967-8), Conchis forces Urfe to watch a pornographic film featuring Lily/July fellating Anton in the dressing room beneath the beach, before offering Urfe the opportunity to ‘punish’ Lily/Julie with a whip in a similar manner to which Conchis was asked by the commander of the German garrison to ‘punish’ the partisans. (Lily/Julie is presented to Urfe, tied to a cross, like a figure in a drama about the Inquisition or perhaps a performer in a bondage-themed stage show.) Like Conchis, Urfe refuses to participate in this public display of sadism. The film’s story, like Fowles’ novel, is structured around a very direct reference to the Madonna/Whore complex outlined by Freud. Urfe is a socially mobile creature, an academic from a working-class background: his father was a bus conductor, and Urfe gained access to university via a scholarship. At a party depicted in one of the film’s flashbacks, Urfe’s publisher describes Urfe: ‘Cracked up. Bad degree. Now classless, rootless [….] All the symptoms of contemporary genius’. Urfe’s relationship with Anne falters owing to an unstated suggestion that Urfe both sees himself as superior to Anne (in terms of education and social class), and regards her as promiscuous. When he arrives on the island of Phraxos, Urfe is told by Meli that the island has only ‘simple pleasures. Nothing to do here except swim, walk, drink ouzo. No women’. ‘Good’, Urfe responds. Upon the island, Urfe seduces Lily/Julie, after Conchis has told Urfe the story of Lily and Urfe believes her to be a product of another, more ‘innocent’ era. It’s clear that in Urfe’s mind, the ‘pure’ Lily – modest and sexually inexperienced – is contrasted with the more modern, ‘earthy’ and independent/sexually liberated Anne who, via some of the film’s flashbacks, is shown in an early encounter with Urfe confessing that she has had a significant number of sexual partners. However, as the narrative progresses Urfe realises that his idealised, innocent Lily is not who he believed her to be: her identity as Julie – perhaps a patient of Conchis’, or an actor in a film he is directing – is revealed to Urfe, and Urfe comes to an awareness that she is not a ghost from another era but rather a flesh and blood product of modern times. In the bizarre trial sequence which features as the film’s climax, the abstract sets and public call to judgement calling to mind the final episodes of Patrick McGoohan’s contemporaneous television series The Prisoner (ITC, 1967-8), Conchis forces Urfe to watch a pornographic film featuring Lily/July fellating Anton in the dressing room beneath the beach, before offering Urfe the opportunity to ‘punish’ Lily/Julie with a whip in a similar manner to which Conchis was asked by the commander of the German garrison to ‘punish’ the partisans. (Lily/Julie is presented to Urfe, tied to a cross, like a figure in a drama about the Inquisition or perhaps a performer in a bondage-themed stage show.) Like Conchis, Urfe refuses to participate in this public display of sadism.

The past works its way into the present, via the suggestion that Lily is a ghost. The modern day, the film suggests, is an era of dissatisfaction and general malaise. ‘One does not have to be [psychic] to see that you are not the happiest of young men’, Conchis tells Urfe before reading Urfe’s fortune via a Tarot deck. ‘I’m just a child of my century’, Urfe responds dryly. Parallels are drawn between Urfe and Conchis, Urfe’s abandoning of Anne mirroring Conchis’ alienation from Lily. ‘The dead live’, Conchis asserts after telling Urfe the story of his relationship with Lily and her death. ‘How?’, Urfe asks. ‘By love’, Conchis declares. When Urfe sees Lily’s ‘ghost’ for the first time, Conchis tells Urfe that Urfe is also psychic. Urfe reacts cynically. ‘Yours is a characteristic reaction of your century to disbelieve, to disprove’, Conchis says, ‘You are like a porcupine. When it has its spines up, it cannot eat; if it cannot eat, it will starve’. Later, after Anne has committed suicide and Conchis has told Urfe what happened on Phraxos during the Second World War, Urfe asks Conchis ‘Why was I cast as the traitor?’ ‘We are all cast as the traitor for one simple reason’, Conchis responds, ‘We have failed to love’. In the film’s climax, Urfe is put on trial for this ‘failure’ to love. The past works its way into the present, via the suggestion that Lily is a ghost. The modern day, the film suggests, is an era of dissatisfaction and general malaise. ‘One does not have to be [psychic] to see that you are not the happiest of young men’, Conchis tells Urfe before reading Urfe’s fortune via a Tarot deck. ‘I’m just a child of my century’, Urfe responds dryly. Parallels are drawn between Urfe and Conchis, Urfe’s abandoning of Anne mirroring Conchis’ alienation from Lily. ‘The dead live’, Conchis asserts after telling Urfe the story of his relationship with Lily and her death. ‘How?’, Urfe asks. ‘By love’, Conchis declares. When Urfe sees Lily’s ‘ghost’ for the first time, Conchis tells Urfe that Urfe is also psychic. Urfe reacts cynically. ‘Yours is a characteristic reaction of your century to disbelieve, to disprove’, Conchis says, ‘You are like a porcupine. When it has its spines up, it cannot eat; if it cannot eat, it will starve’. Later, after Anne has committed suicide and Conchis has told Urfe what happened on Phraxos during the Second World War, Urfe asks Conchis ‘Why was I cast as the traitor?’ ‘We are all cast as the traitor for one simple reason’, Conchis responds, ‘We have failed to love’. In the film’s climax, Urfe is put on trial for this ‘failure’ to love.

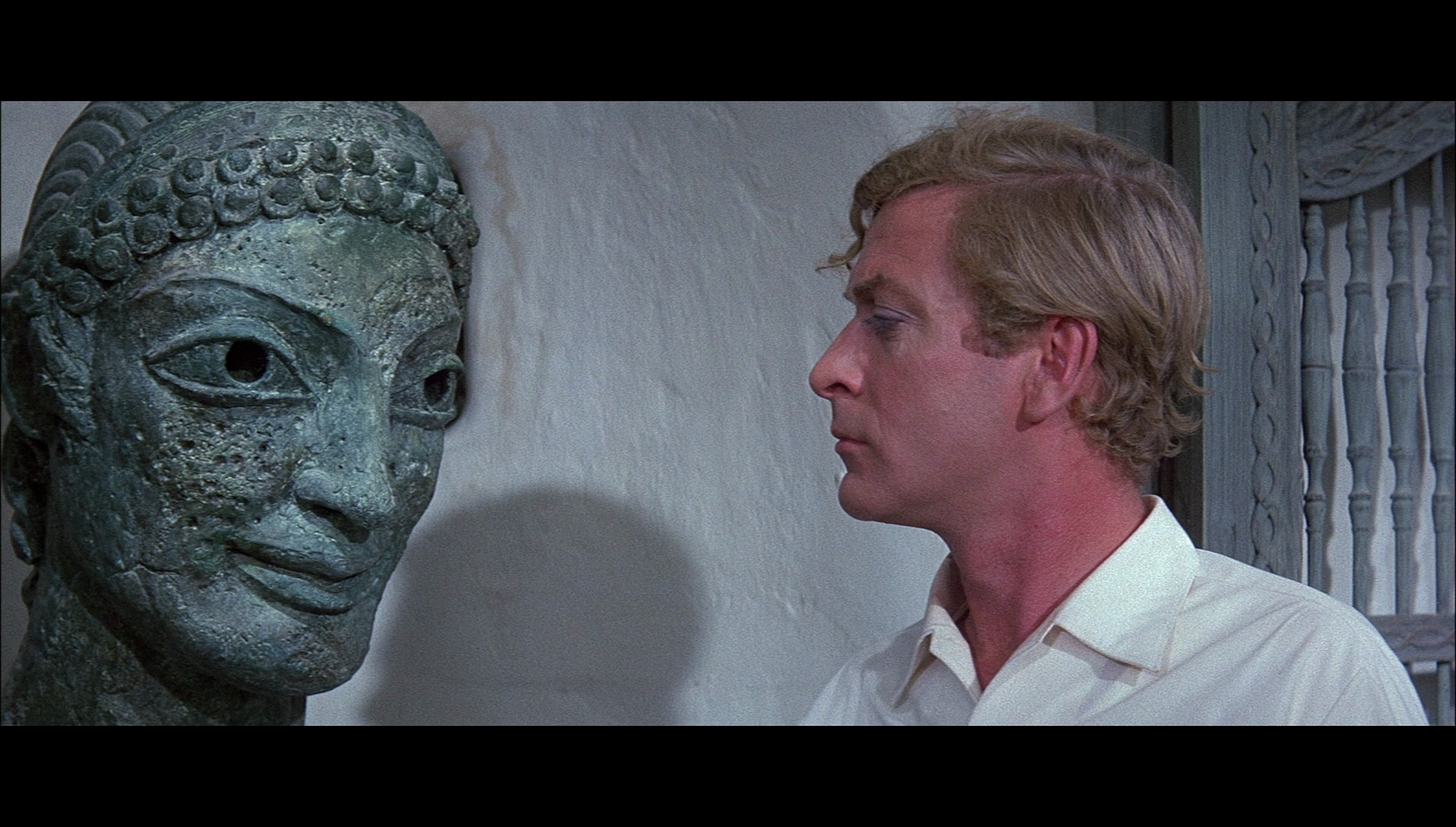

Conchis’ role is ambiguous throughout, the narrative constantly destabilising our perception of both his character and the character of Lily/Julie. Whatever the precise nature of his role, however, Conchis lords over the events, manipulating the lives of Urfe and Lily/Julie. ‘He’s some kind of voyeur, and we’re his puppets, his toys’, Lily/Julie asserts at one point in the narrative. (The ambiguity surrounding Conchis’ precise role, his use of rituals and magickal symbols, and the reference to other characters being his ‘puppets’ may very well have influenced Telly Savalas’ role as Leandro, the puppetmaster, in Mario Bava’s 1973 Gothic horror picture Lisa e il diavolo/Lisa and the Devil.) The amplification of Conchis’ role as ‘puppetmaster’, with his claim/revelation that he is a film producer and Urfe is the unwitting star of his latest picture, leads the film along an increasingly metafictional path. ‘You have entered the Metatheatre’, Conchis tells Urfe, ‘A theatre with no set plot, no set dialogue and no audience. Our play is for the actors alone’. In response to this, Urfe asks Conchis if he is to be ‘the unpaid clown for your production’ – with Anne’s suicide functioning as ‘the unpaid bill for your amusements’.  The protagonist of Fowles’ novel is younger than the Urfe of the film: Caine was in his early 30s when he played the part, and the novel’s Urfe is a recent graduate aged just 25. Fowles’ book is a novel best read in youth: rereading the book as an adult, the Urfe of the novel comes across as whiningly self-absorbed. Fowles himself described the protagonist as ‘meant to be a kind of ever modern man, confused, and looking for something he does not know. Always afraid to make a commitment to himself, or to life’ (Fowles, quoted in Arnold, 2002: 180). In front of an audience and on an abstract set, the bizarre nature of the proceedings amplified by the photography (which features what seems to be Vaseline smeared on the edges of the lens), Urfe is confronted with a computer that reads out the charges against him: ‘The subject is devoid of interest’, the computer says, ‘He is a machine for his own gratification, not a human being. He is shallow, he is vain, he is egocentric, he is a liar. There is no hope for him’. The ‘trial’ results in Urfe refusing to harm Lily/Julie for her perceived transgressions (as depicted in the film Urfe is forced to watch in which Julie fellates Anton). Urfe awakens inhospital. ‘You have been ill’, Conchis says, standing by Urfe’s bedside, ‘but I think you have recovered’. ‘Due to your excellent treatment?’, Urfe asks ironically, ‘What you do, is it for us or for yourself – because of what you did in the war? Just once, the truth’. ‘What is the truth?’, Conchis asks. The intention of the film’s final shot is to show that Nicholas has internalised the ‘lessons’ he has learnt from Conchis, and now realises ‘that human systems are artificial constructs that he must regard with amused, ironic detachment—with a smile’ (Aubrey, 2015b: 42). However, where the novel attempts to make this clear, the film simply presents this resolution to the story via an enigmatic shot of Caine staring at a Greek statue; ‘it is small wonder’, James Aubrey notes, ‘that audiences seeing The Magus for the first time felt bafflement more often than enlightenment’ (ibid.). The protagonist of Fowles’ novel is younger than the Urfe of the film: Caine was in his early 30s when he played the part, and the novel’s Urfe is a recent graduate aged just 25. Fowles’ book is a novel best read in youth: rereading the book as an adult, the Urfe of the novel comes across as whiningly self-absorbed. Fowles himself described the protagonist as ‘meant to be a kind of ever modern man, confused, and looking for something he does not know. Always afraid to make a commitment to himself, or to life’ (Fowles, quoted in Arnold, 2002: 180). In front of an audience and on an abstract set, the bizarre nature of the proceedings amplified by the photography (which features what seems to be Vaseline smeared on the edges of the lens), Urfe is confronted with a computer that reads out the charges against him: ‘The subject is devoid of interest’, the computer says, ‘He is a machine for his own gratification, not a human being. He is shallow, he is vain, he is egocentric, he is a liar. There is no hope for him’. The ‘trial’ results in Urfe refusing to harm Lily/Julie for her perceived transgressions (as depicted in the film Urfe is forced to watch in which Julie fellates Anton). Urfe awakens inhospital. ‘You have been ill’, Conchis says, standing by Urfe’s bedside, ‘but I think you have recovered’. ‘Due to your excellent treatment?’, Urfe asks ironically, ‘What you do, is it for us or for yourself – because of what you did in the war? Just once, the truth’. ‘What is the truth?’, Conchis asks. The intention of the film’s final shot is to show that Nicholas has internalised the ‘lessons’ he has learnt from Conchis, and now realises ‘that human systems are artificial constructs that he must regard with amused, ironic detachment—with a smile’ (Aubrey, 2015b: 42). However, where the novel attempts to make this clear, the film simply presents this resolution to the story via an enigmatic shot of Caine staring at a Greek statue; ‘it is small wonder’, James Aubrey notes, ‘that audiences seeing The Magus for the first time felt bafflement more often than enlightenment’ (ibid.).

Video

The film runs for 116:16 mins and is uncut. Taking up approximately 31Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Signal One’s 1080p presentation of The Magus uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film’s colour 35mm photography (by Billy Williams) is beautiful, characters’ faces frequently framed against the deep blue water or sky, objets d’art littering the frame. The image as presented on Signal One’s new Blu-ray is crisp and detailed, retaining the structure of 35mm film thanks to a strong encode. The film was shot on location in Spain and Greece, and the Mediterranean sun beats down in every frame, harsh and direct sunlight illuminating the actors faces whilst casting deep shadow behind them or behind the objects in the frame. This presentation handles this superbly, nicely balanced contrast levels offering strongly defined midtones and deep blacks. A very good level of fine detail is present throughout the film, especially noticeable in close-ups of the actor’ faces. There is no damage to speak of. The light flooding the frame results in most of the shots being staged in depth, this depth of field communicated excellently here. In all, it’s a very pleasing presentation of the film. The film runs for 116:16 mins and is uncut. Taking up approximately 31Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Signal One’s 1080p presentation of The Magus uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film’s colour 35mm photography (by Billy Williams) is beautiful, characters’ faces frequently framed against the deep blue water or sky, objets d’art littering the frame. The image as presented on Signal One’s new Blu-ray is crisp and detailed, retaining the structure of 35mm film thanks to a strong encode. The film was shot on location in Spain and Greece, and the Mediterranean sun beats down in every frame, harsh and direct sunlight illuminating the actors faces whilst casting deep shadow behind them or behind the objects in the frame. This presentation handles this superbly, nicely balanced contrast levels offering strongly defined midtones and deep blacks. A very good level of fine detail is present throughout the film, especially noticeable in close-ups of the actor’ faces. There is no damage to speak of. The light flooding the frame results in most of the shots being staged in depth, this depth of field communicated excellently here. In all, it’s a very pleasing presentation of the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is rich and deep, offering as much range as is needed and showcasing John Dankworth’s interesting score for the picture. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘John Fowles: The Literary Magus’ (22:45). Previously included on the film’s 2006 DVD release, this featurette focuses on Fowles’ work and features comments from Eileen Warburton, Fowles’ biographer; Bob Goosmann, a fan of Fowles’ fiction; Dianne Vipond, a lecturer; book editor Ray Roberts; David Tringham, with whom Fowles worked on The Last Chapter; and Fowles’ stepdaughter Anna Christy. - ‘Enchanted Island’ (22:03). In a new interview, Guy Green’s son Michael recalls the shooting of the picture, which provided the then-seventeen year old Michael Green with his first job on a film set. - ‘Guy Green – A Life Behind the Camera’ (22:22). In another new interview, the film’s director Guy Green talks about his career, discussing his work as a cinematographer for directors such as David Lean, before progressing on to working as a director. Guy Green’s comments are supported with some brief inserts featuring Michael Green talking about his father. - ‘Billy Williams Talks About The Magus’ (12:15). The film’s cinematographer discusses his work on The Magus, suggesting that Caine was responsible for Williams being asked to shoot the picture owing to his work with Caine on Ken Russell’s Billion Dollar Brain (1967). Williams praises Green’s work as a cinematographer, referring to Green as a ‘master of light’. Williams talks about the decision to shoot the film on Mallorca (owing to the revolution that had taken place recently within Greece, which made shooting in Greece impossible) and discusses some of the issues with the extremely bright light ‘which was troublesome to some of the actors, particularly those with blue eyes’ such as Caine and, in particular, Bergen. - ‘Time Hutchison Talks About The Magus’ (10:22). The son of the film’s art director, William Hutchison, talks about the picture, reflecting on the choice of locations used in the shoot and his memories of the making of the film. - ‘Stephanie Kaye Talks About The Magus’ (5:43). The film’s hairdresser, Stephanie Kaye, reflects on the styling of Anthony Quinn’s hair in the film and talks about her memories of the performers. - Trailer (1:01).

Overall

At one point in the film, Urfe tells Conchis that ‘I’ll just enjoy it more if I knew what it was all about’. For some members of the audience, The Magus will be frustratingly ambiguous, but it's a film that may reward those viewers who (in contravention of Woody Allen's feelings about the picture) choose to watch it more than once - its 'secrets' presenting themselves gradually. As noted above, it has some interesting parallels with The Prisoner and Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil, its themes feeling very much ‘of the period’. The influence of New Wave cinemas is writ large throughout the picture, especially in its fractured and non-linear representation of time. It’s an interesting film, not wholly effective, but certainly more rewarding than its reputation (frequently based on Woody Allen’s aforementioned quip about the picture) might suggest. At one point in the film, Urfe tells Conchis that ‘I’ll just enjoy it more if I knew what it was all about’. For some members of the audience, The Magus will be frustratingly ambiguous, but it's a film that may reward those viewers who (in contravention of Woody Allen's feelings about the picture) choose to watch it more than once - its 'secrets' presenting themselves gradually. As noted above, it has some interesting parallels with The Prisoner and Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil, its themes feeling very much ‘of the period’. The influence of New Wave cinemas is writ large throughout the picture, especially in its fractured and non-linear representation of time. It’s an interesting film, not wholly effective, but certainly more rewarding than its reputation (frequently based on Woody Allen’s aforementioned quip about the picture) might suggest.

Signal One’s Blu-ray release contains an excellent presentation of the film that is supported with some very good contextual material. It’s a great release of an interesting, though not wholly successful, film. References: Arnold, Eve, 2002: Film Journal. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Aubrey, James, 2015a: ‘Introduction’. In: Aubrey, James (ed), 2015: Filming John Fowles: Critical Essays on Motion Picture and Television. London: McFarland and Company: 1-12 Aubrey, James, 2015b: ‘The Magus on Film’. In: Aubrey, James (ed), 2015: Filming John Fowles: Critical Essays on Motion Picture and Television. London: McFarland and Company: 35-52 Hall, William, 2007: Sir Michael Caine – The Biography. John Blake Publishing Sutherland, John, 2011: Lives of the Novelists: A History of Fiction in 294 Lives. Yale University Press

|

|||||

|