|

|

My Life as a Dog AKA Mitt liv som hund (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd May 2017). |

|

The Film

My Life as a Dog (Lasse Hallstrom, 1985) My Life as a Dog (Lasse Hallstrom, 1985)

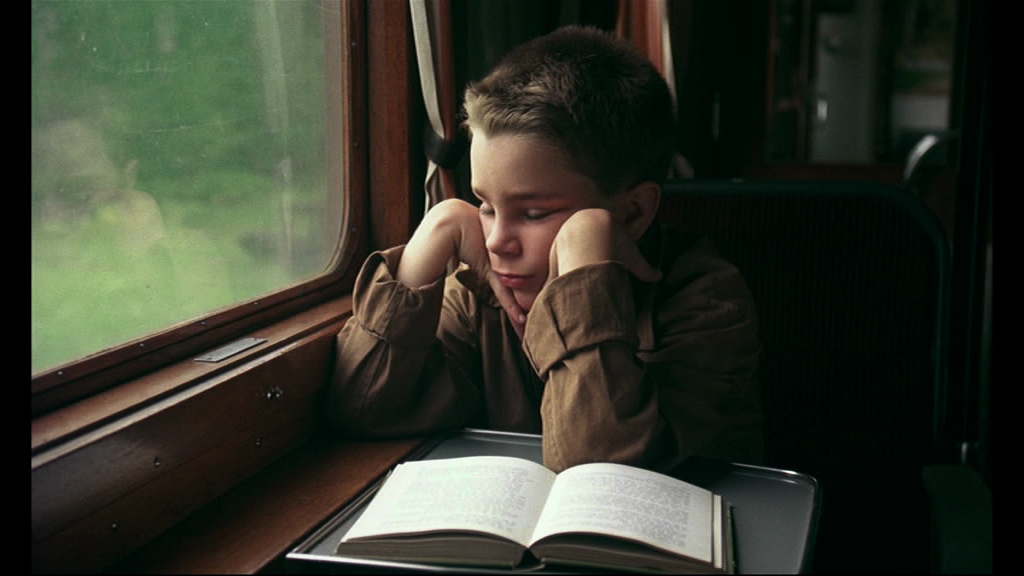

Adapted from the autobiography by Reidar Jonsson, which director Lasse Hallstrom discovered in 1983, My Life as a Dog was made in 1985 before finding international release in 1987; its release in America was followed by the film being nominated for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay in that year’s Academy Awards. The success of My Life as a Dog in America led to Hallstrom being invited to work for Universal, where he made Once Around (1991) before directing the highly-acclaimed youth drama What’s Eating Gilbert Grape in 1993. Taking place in the 1950s, the film focuses on Ingemar (Anton Glanzelius), a young boy on the cusp of adolescence who lives with his spiteful older brother and his ailing mother (Anki Liden), who is suffering from tuberculosis. Though Ingemar’s mother’s patience has been worn thin by her illness, resulting in fits of rage, Ingemar dotes after his parent. (His father is away at sea, we are told.) Ingemar also lives his life for his beloved dog, Sickan. After Ingemar accidentally sets fire to a tip on which he is playing with Sickan, he and his brother are sent away: Ingemar’s brother is sent to their grandma’s house, and Ingemar is sent to stay with his uncle Gunnar (Tomas von Bromssen) and Gunnar’s wife Ulla (Kicki Rundgren). However, Ingemar is unable to take Sickan with him, and so Ingemar is told Sickan will be sent to stay at a kennel. Gunnar is a joker, and he and Ingemar form a strong bond. However, Gunnar is also childlike and irresponsible. Ingemar also forms a friendship with the elderly Mr Arvidsson (Didrik Gustafsson), who is dying. Whilst living with Gunnar, Ingemar makes some new friends his own age, including Manne (Jan-Philip Hollstrom), who inexplicably has green hair, and tomboy Saga (Melinda Kinnaman). Saga likes to play football and box, and she bests Ingemar at both sports.  At the glass factory where Gunnar works, Ingemar also meets the buxom blonde Berit (Ing-Marie Carlsson). Berit and Ingemar form a friendship, and Berit asks Ingemar to accompany her to the studio of a local artist (Lennart Hjulstrom); the artist plans to make a sculpture of Berit, and Ingemar essentially functions as Berit’s chaperone whilst she poses in the nude. At the glass factory where Gunnar works, Ingemar also meets the buxom blonde Berit (Ing-Marie Carlsson). Berit and Ingemar form a friendship, and Berit asks Ingemar to accompany her to the studio of a local artist (Lennart Hjulstrom); the artist plans to make a sculpture of Berit, and Ingemar essentially functions as Berit’s chaperone whilst she poses in the nude.

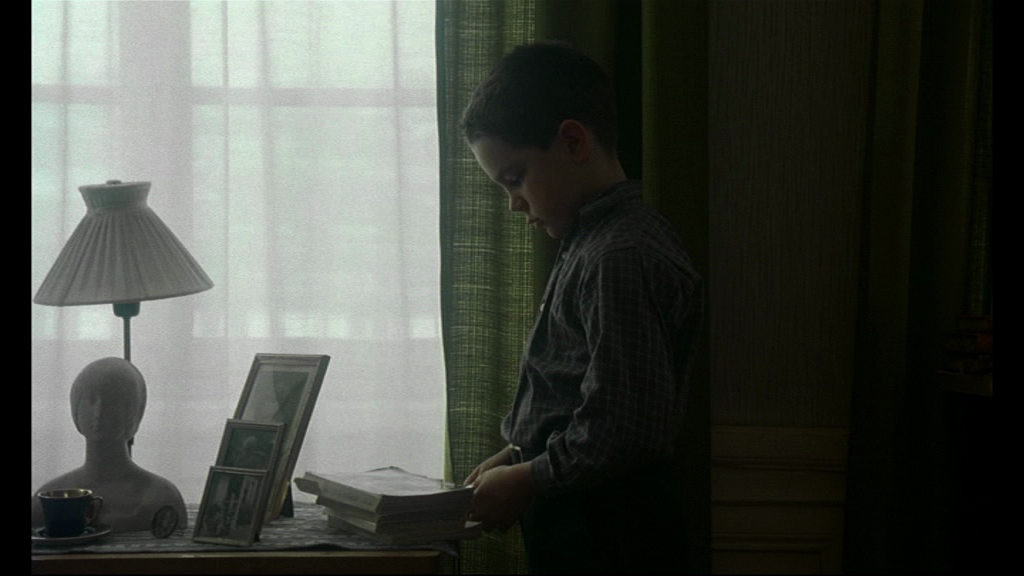

Eventually, Ingemar returns home to live with his mother and brother. However, his mother’s health takes a turn for the worst; she is hospitalised, and Ingemar and his brother spend time with a male relative whose wife argues over the presence of the two young boys. When Ingemar’s mother dies, he is sent once again to live with Gunnar and Ulla. Ingemar pines for Sickan, but soon he is forced to face the fact that Sickan, whom Ingemar believed to still be at the kennel, is no longer alive. The film is one of a long line of European films to focus on youth, from Jean Vigo’s Zero de couduite (Zero for Conduct, 1933) and Francois Truffaut’s Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959) to Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso (1988). More specifically, the coming of age story has a longstanding importance for Scandinavian audiences, from Bjarne Henning-Jensen’s 1946 picture Ditte, Child of Man to Lukas Moodyson’s Fucking Amal (1998). However, My Life as a Dog was released at a time when American cinema too had increasingly become fascinated with ‘coming of age’ stories, which like My Life as a Dog were often set in the not-so-distant past, including George Lucas’ American Graffiti (1973) and the spate of similar films that appeared in the 1980s (Rob Reiner’s Stand By Me, 1986; Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish, 1983). Within this context, My Life as a Dog received substantial critical acclaim outside Sweden; following its US release in 1987, it was nominated for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay in the 1987 Academy Awards. With the international success of My Life as a Dog, Lasse Hallstrom found the doors to a career in Hollywood cinema opening, and in Hollywood he continued to make films about the rites of passage to adulthood (What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, 1993; The Cider House Rules, 1999) and humankind’s relationship with animals (Hachi: A Dog’s Tale, 2009; the recent film A Dog’s Purpose, 2017).  With his transition into adulthood, Ingemar becomes increasingly aware of sex and sexuality. Near the start of the film, Ingemar listens as his older brother explains his rudimentary knowledge of sex to a group of other children, before asking Ingemar to ‘demonstrate’ by placing his penis in a bottle. Of course, Ingemar’s penis becomes stuck in the bottle, and Ingemar and his brother are caught by their mother. ‘Why do you do these things?’, the mother asks. ‘I don’t know. I guess it’s the menopause’, Ingemar responds innocently. Later, whilst he is staying with Gunnar, Ingemar is asked by Mr Arvidsson to read the contents of the lingerie catalogue, provoking Ingemar’s curiosity about the opposite sex. Shortly afterwards, Saga tells Ingemar she is growing breasts and fears that this will result in her being thrown off the football team. She asks Ingemar to help tie her breasts down, so that they are not noticeable through her shirt. Much later in the film, after Ingemar’s mother has died and he has returned to live with Gunnar, Saga once again shows Ingemar her breasts and asks him if he would like to feel them. Ingemar is embarrassed and leaves; rejected, Saga argues with Ingemar, leading to a boxing match between Ingemar and Saga in which Ingemar is humiliated even further – something which eventually leads to Ingemar’s confession to Gunnar that he feels responsible for the death of his mother, and that he feels that she rejected him. With his transition into adulthood, Ingemar becomes increasingly aware of sex and sexuality. Near the start of the film, Ingemar listens as his older brother explains his rudimentary knowledge of sex to a group of other children, before asking Ingemar to ‘demonstrate’ by placing his penis in a bottle. Of course, Ingemar’s penis becomes stuck in the bottle, and Ingemar and his brother are caught by their mother. ‘Why do you do these things?’, the mother asks. ‘I don’t know. I guess it’s the menopause’, Ingemar responds innocently. Later, whilst he is staying with Gunnar, Ingemar is asked by Mr Arvidsson to read the contents of the lingerie catalogue, provoking Ingemar’s curiosity about the opposite sex. Shortly afterwards, Saga tells Ingemar she is growing breasts and fears that this will result in her being thrown off the football team. She asks Ingemar to help tie her breasts down, so that they are not noticeable through her shirt. Much later in the film, after Ingemar’s mother has died and he has returned to live with Gunnar, Saga once again shows Ingemar her breasts and asks him if he would like to feel them. Ingemar is embarrassed and leaves; rejected, Saga argues with Ingemar, leading to a boxing match between Ingemar and Saga in which Ingemar is humiliated even further – something which eventually leads to Ingemar’s confession to Gunnar that he feels responsible for the death of his mother, and that he feels that she rejected him.

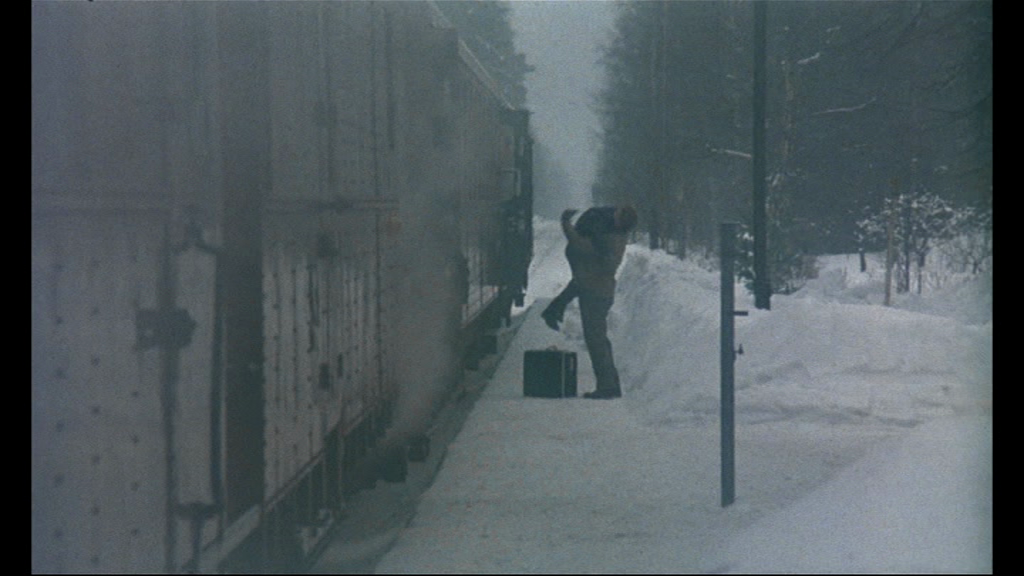

Ingemar also becomes fascinated with the pretty but much older Berit, who flirts gently with the boy. ‘Who are you in love with today?’ Berit asks Ingemar at one point in the film. ‘You, of course’, he responds. ‘But I’m an old lady, aren’t I?’, she jokes. When Berit is asked by the village artist to post nude for the statue he plans to make, Ingemar becomes obsessed with the idea of seeing Berit without her clothes. The film suggests that Berit takes Ingemar along to the sittings with the intention of Ingemar functioning essentially as her chaperone, ensuring that the artist does not overstep his mark. ‘Why should I go in there? I’m only in the way’, Ingemar tells Berit. ‘What’s wrong with that?’, Berit responds. When Gunnar hears of Ingemar’s excursions with Berit, Gunnar exhibits barely-concealed jealousy. ‘How were her boob?’, Gunnar asks Ingemar in reference to Berit. However, during the sittings Ingemar is placed in a room outside that in which Berit is posing; straining to see through the door, Ingemar decides to climb on the roof of the building and observe the nude Berit via the skylight. Predictably, Ingemar falls through the skylight, shocking both Berit and the artist. He lands almost atop Berit. ‘If you keep on like that, you’ll not be confirmed’, Berit jokes after ensuring that Ingemar is uninjured. ‘If so, it was worth it’, Ingemar jokes back.  A sensitive boy, Ingemar copes by comparing his situation with those of other people, giving himself a sense of perspective and objectivity towards his experiences and enabling him to manage the trials and tribulations life throws at him. These comparisons are made in Ingemar’s voiceover narration, in which at several points he explicitly underscores the value of gaining objectivity towards one’s own experiences (‘I’ve been lucky, compared to others. You have to compare, so you can get a little distance from things’, Ingemar narrates); these points of narration are accompanied by images depicting Ingemar on a beach with his mother, his mother laughing at Ingemar’s playfulness. It’s unclear whether these images are memories of a time before Ingemar’s mother’s illness, or fantasies conjured by Ingemar in response to his mother’s predicament and current dour temperament. Certainly, in the footage we see of Ingemar’s mother that takes place in the diegetic present, she is largely a severe presence, her reactions to Ingemar’s behaviour often violent – even when he spills his milk at the breakfast table, the result of a muscle spasm which takes place whenever he holds a glass of liquid in front of others. Ingemar’s mother screams at Ingemar and his brother; in contrast with her relationship with the two boys, uncle Gunnar’s carefree attitude is a shock to the child’s system. When Ingemar’s mother dies, Gunnar meets Ingemar at the railway station with a warm hug. As Mrs Avidsson tells Ingemar following the death of her husband, ‘Life is hard sometimes. It’s not easy being left alone’. Towards the end of the film, after Ingemar’s disagreement with Saga has spiralled, Ingemar is consoled by Gunnar. Ingemar confesses to Gunnar that he believes that he killed his mother, and Ingemar also tells Gunnar that he feels his mother rejected him: ‘Why didn’t you want me, mum?’, Ingemar sobs, ‘Why didn’t you want me?’ A sensitive boy, Ingemar copes by comparing his situation with those of other people, giving himself a sense of perspective and objectivity towards his experiences and enabling him to manage the trials and tribulations life throws at him. These comparisons are made in Ingemar’s voiceover narration, in which at several points he explicitly underscores the value of gaining objectivity towards one’s own experiences (‘I’ve been lucky, compared to others. You have to compare, so you can get a little distance from things’, Ingemar narrates); these points of narration are accompanied by images depicting Ingemar on a beach with his mother, his mother laughing at Ingemar’s playfulness. It’s unclear whether these images are memories of a time before Ingemar’s mother’s illness, or fantasies conjured by Ingemar in response to his mother’s predicament and current dour temperament. Certainly, in the footage we see of Ingemar’s mother that takes place in the diegetic present, she is largely a severe presence, her reactions to Ingemar’s behaviour often violent – even when he spills his milk at the breakfast table, the result of a muscle spasm which takes place whenever he holds a glass of liquid in front of others. Ingemar’s mother screams at Ingemar and his brother; in contrast with her relationship with the two boys, uncle Gunnar’s carefree attitude is a shock to the child’s system. When Ingemar’s mother dies, Gunnar meets Ingemar at the railway station with a warm hug. As Mrs Avidsson tells Ingemar following the death of her husband, ‘Life is hard sometimes. It’s not easy being left alone’. Towards the end of the film, after Ingemar’s disagreement with Saga has spiralled, Ingemar is consoled by Gunnar. Ingemar confesses to Gunnar that he believes that he killed his mother, and Ingemar also tells Gunnar that he feels his mother rejected him: ‘Why didn’t you want me, mum?’, Ingemar sobs, ‘Why didn’t you want me?’

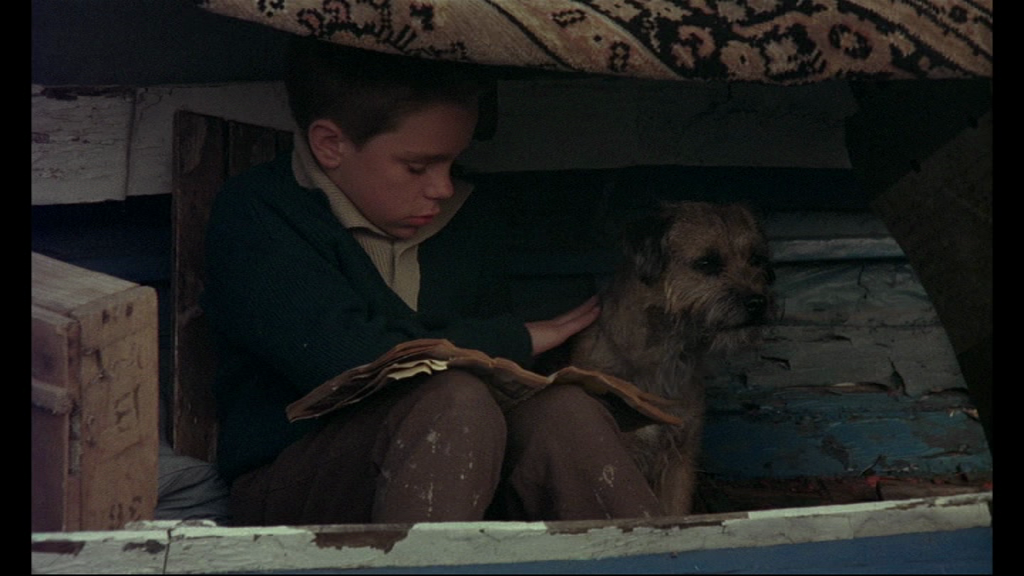

In this context, Ingemar’s relationship with Sickan is a parallel for his relationship with his mother, and following Ingemar’s mother’s death, Ingemar clings to the belief that he’ll be reunited with Sickan; the events of the climax are precipitated both by Saga’s suggestion of sexual interest in Ingemar and in Saga’s assertion that Sickan must surely be dead – that Ingemar’s belief that Sickan is safe in the kennel is a lie. In this context, Ingemar’s relationship with Sickan is a parallel for his relationship with his mother, and following Ingemar’s mother’s death, Ingemar clings to the belief that he’ll be reunited with Sickan; the events of the climax are precipitated both by Saga’s suggestion of sexual interest in Ingemar and in Saga’s assertion that Sickan must surely be dead – that Ingemar’s belief that Sickan is safe in the kennel is a lie.

Dogs are a recurring leitmotif within the film. Ingemar frequently compares his situation with that of Laika, the Soviet space dog who starved to death whilst orbiting the Earth. Having been sent in exile, to stay with his uncle Gunnar and Gunnar’s wife Ulla, Ingemar sees in the story of Laika a parallel to his own life; the dog’s helplessness mirrors Ingemar’s own lack of autonomy over his fate. Ingemar’s response to severe stressors is to pretend to be a dog, crawling around the floor and barking; for a dog, the world is meant to be unknowable. Upon being told that Sickan is most likely dead, Ingemar retreats into this alternate persona. Hallstrom’s film is episodic, heartfelt and unsentimental. It’s a bold, striking film that fits into the paradigms of both European – and specifically Scandinavian – films about the ‘coming of age’ and the then-popular American films about similar issues. Like many of those American films, My Life as a Dog takes as its setting a period in the recent past (the 1950s, as in American Graffiti and Stand By Me) and juxtaposes urban life with life in rural enclaves; Ingemar’s experiences away from the city help him to ‘heal’ and introduce him to a group of friends, something that, it seems, is key absence in his life back home.

Video

Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were provided with a check disc of the DVD included in this release only. Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were provided with a check disc of the DVD included in this release only.

Released in a Blu-ray/DVD combo pack, Arrow Academy’s presentation of My Life as a Dog is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.66:1 (with anamorphic enhancement on the DVD provided for review). The film is uncut; the running time of the DVD presentation is 97:29 mins (PAL). The film is shot in a mostly naturalistic style, with the inserts of Ingemar and his mother during happier times being presented with diffuse light and shot in a contre-jour style, the glow providing the figures with a halo-like effect and enhancing the idealistic nature of these scenes. The presentation is clear and free from damage. The 35mm colour photography is represented well here, with naturalistic colours and skintones that seem accurate. A good level of detail is present throughout the standard definition presentation on the DVD we were given for review. It’s a pleasing presentation; one can only assume that the Blu-ray presentation, if true to source, is equally impressive.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Swedish Dolby Digital 2.0 track with optional English subtitles. The audio track is fine: it’s clear and rich. The subtitles are easy to read and free from grammatical or typographical errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - ‘Come On, Then!’ (36:29). Made in 1981, this half hour television drama was directed by Hallstrom. It focuses on a footballer who reflects on his life upon his retirement from the game at the age of 35. Shot on videotape, it’s presented in the 1.33:1 ratio and is in Swedish with optional English subtitles. Beginning with the coach’s motivational speech prior to a football game, this feels very much like something Alan Clarke might have made for the BBC’s Wednesday Play strand. A reflection on age and the changes that took place in the 1960s and 1970s, it’s arguably as interesting as the main feature and is definitely worth watching. - Trailer (2:40). Retail copies include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet containing an article about the film by Peter Walsh.

Overall

My Life as a Dog is an excellent film about youth, as potent today as it was in the 1980s. The film’s themes of loss and transition have an arguably universal relevance, and whilst the picture is very clearly a Swedish film, it’s easy to see why it was so successful amongst international audiences – especially in America, where it led to Hallstrom being associated with some fascinating projects which continue to explore some of the themes outlined in this film. My Life as a Dog is an excellent film about youth, as potent today as it was in the 1980s. The film’s themes of loss and transition have an arguably universal relevance, and whilst the picture is very clearly a Swedish film, it’s easy to see why it was so successful amongst international audiences – especially in America, where it led to Hallstrom being associated with some fascinating projects which continue to explore some of the themes outlined in this film.

For the purposes of our review, we were only provided with a check disc of the DVD copy from Arrow Academy’s release, but the presentation of the main feature on the DVD is very pleasing – and one can only assume that if the Blu-ray disc has a solid encode (which, given Arrow Academy’s track record, is a very safe assumption to make), the Blu-ray disc offers a very good presentation too. Aside from the trailer, the sole audiovisual extra is Hallstrom’s 1981 television production ‘Come On, Then!’, which, I’d argue, is equally as good as the main feature. In all, this is a very good release of a significant film.

|

|||||

|