|

|

Cops vs Thugs AKA Kenkei tai soshiki boryoku (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st May 2017). |

|

The Film

Cops Vs Thugs (Fukasaku Kinji, 1975) Cops Vs Thugs (Fukasaku Kinji, 1975)

Fukasaku Kinji made Cops Vs Thugs between the production of the three films which made up the New Battles Without Honor and Humanity series. With his early 1970s films, Fukasaku became a director who was closely associated with gritty ‘ripped from the headlines’ tales of yakuza, depicting the world of organised crime in shades of grey and suggesting that legitimate structures of authority (police, business and politics) were just as corrupt – if not more so – than the world of the yakuza. Cops Vs Thugs is extremely similar to the Battles Without Honor and Humanity films in its worldview and aesthetic; and that’s certainly not a criticism, because despite the repetition of themes and visual tropes, Fukasaku’s yakuza films are consistently exciting. The narrative of Cops Vs Thugs takes place in Kurashima City during 1963. In the film, based on a true story, corrupt cop Kuno (Sugawara Bunta) lives in the pocket of yakuza Hirotani Kenji (Matsukata Hiroki), having saved Hirotani from facing conviction for the murder of Boss Miyaki six years prior. Hirotani is acting boss of the Ohara gang whilst Boss Ohara is serving a long-term prison sentence. Meanwhile, the head of a rival clan, Kawade Katsumi (Narita Mikio), is in league with a crooked politician, Tomayasu. Tomayasu is the former head of a yakuza clan who disbanded his faction in 1960, before being elected to local government in 1962. Tomayasu was Kawade’s mentor during Kawade’s years as a junior yakuza. When Hirotani’s hoods tear up one of Kawade’s clubs, in response to Kawade’s clan selling dope for the Shinmei group on territory run by the Ohara family, tensions between Kawade and Hirotani escalate. Kuno persuades his boss, Chief Ikeda (Fujioka Jukei), to accept Hirotani’s suggestion that the attack on Kawade’s club was in response to a small-time hood’s infatuation with one of the hostesses, Mariko. However, Hirotani asks Kuno to help him take care of the situation with Kawade.  Kuno discovers that Sanyo Oil is planning to auction off some of their valuable land, and a company named Nikko Oil wishes to buy it and use the land as ‘a place for more oil tanks’. However, the local fisherman’s union has prohibited this, believing that Nikko Oil’s planned use for the land will contaminate the fishing waters nearby. Tomayasu and Kawade are plotting to use Kawade’s business Ocean Tours as a shell company, purchasing the land from Sanyo Oil ostensibly to develop as a site of leisure, but secretly intending to sell the land to Nikko Oil at a significant profit. Kuno discovers that Sanyo Oil is planning to auction off some of their valuable land, and a company named Nikko Oil wishes to buy it and use the land as ‘a place for more oil tanks’. However, the local fisherman’s union has prohibited this, believing that Nikko Oil’s planned use for the land will contaminate the fishing waters nearby. Tomayasu and Kawade are plotting to use Kawade’s business Ocean Tours as a shell company, purchasing the land from Sanyo Oil ostensibly to develop as a site of leisure, but secretly intending to sell the land to Nikko Oil at a significant profit.

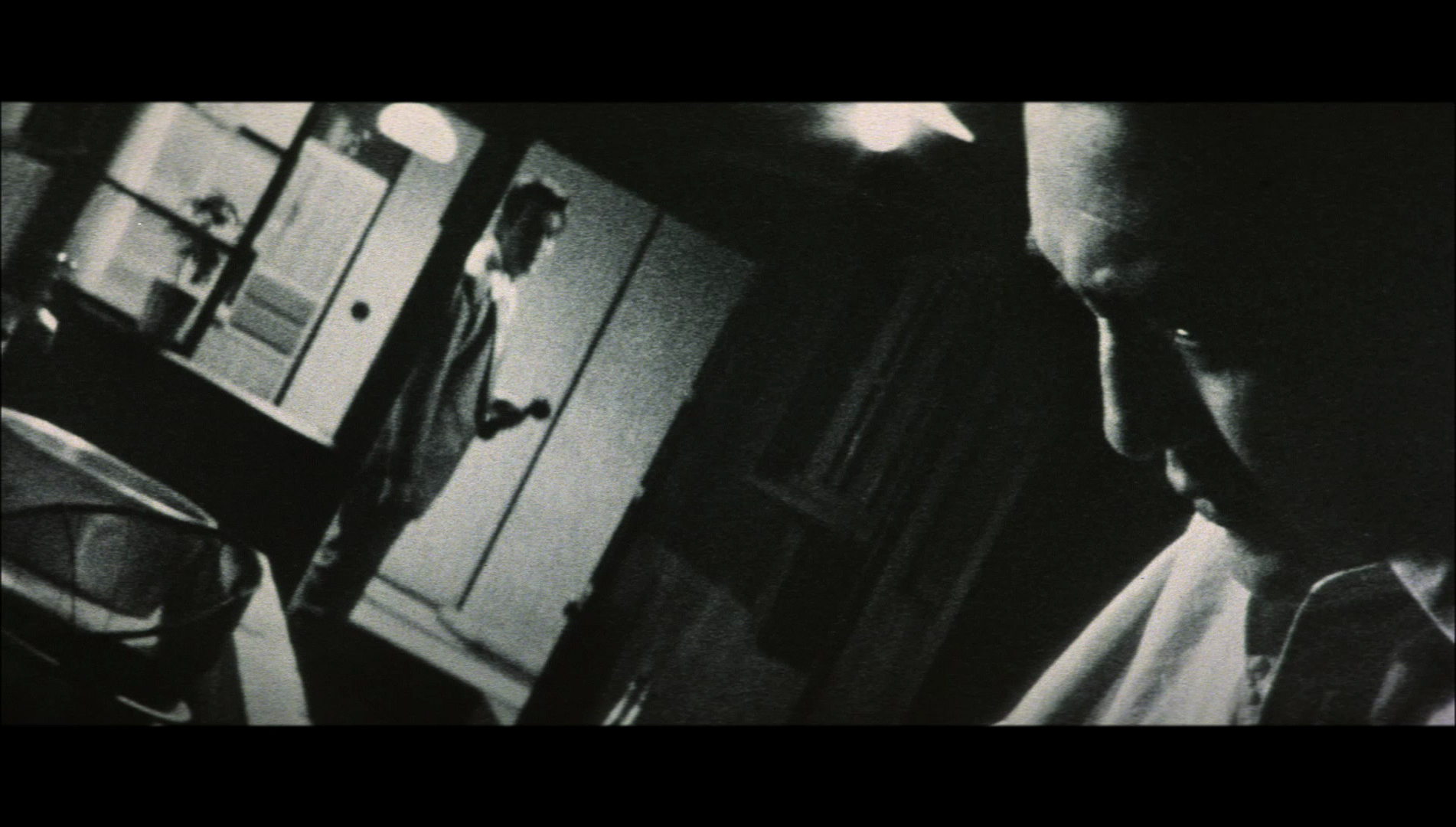

Kuno engineers a plan which will allow him to arrest Kawade, thus causing the deal between Sanyo Oil and Ocean Tours to fall through and leading the Ohara clan into possession of the land. However, things become increasingly complicated when the Prefecture Police Commissioner, Kikuchi, makes plans to clean up corruption within the police force. Kuno is gradually forced into choosing between his allegiance to Hirotani and his work as an officer of the law. In the 1950s and 1970s, the mukokuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) films of Nikkatsu, which began with Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun in 1956, brought tales of the yakuza into the present-day. Prior to those pictures, the yakuza had usually been featured in jidaigeki pictures (period dramas). Those jidaigeki films predominantly featured Westernised villains and depicted the moral code of the yakuza in a largely positive light, as a ‘pure’ system of values that was in contrast with the more ‘corrupt’ Westernised values of the modern world. The mukokuseki akushon films, on the other hand, featured Westernised heroes in contemporary urban settings, and almost invariably offered an implicit (if not explicit) critique of the code of the yakuza which was buried in an exploration of inter-generational conflict: in those films, the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans were frequently depicted as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. However, as Jasper Sharp has noted, despite their modern-day settings, the mokukuseki akushon pictures ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182).  The mukokuseki akushon films brought yakuza stories up to date, featuring individualistic heroes who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes in film noir-esque chiarsoscuro lighting. The early mukokuseki akushon films were often photographed in monochrome, something which enhanced their similarities with American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s – and European films noir of the 1950s and 1960s too (including Jules Dassin’s Rififi, 1955, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le deuxieme souffle, 1966). Later examples of the mukokuseki akushon, however, were more frequently shot in colour, developing into mudo akushon (‘mood action’) and nyu akushon (‘new action’) films; these two forms were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were even more morally ambiguous than their predecessors. Eventually, in the 1970s, these would be supplanted by jitsuroku pictures like Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series and the same director’s Street Mobster (1971), which is usually cited as one of the first examples of jitsuroko cinema. These jitsuroku films could be likened to the semidocumentary films noir such as Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street (1945), employing documentary-style camerawork and abrupt editing rhythms alongside storylines which more often than not were based in true accounts of life within the yakuza (or, at the very least, were claimed to be based on such accounts). The mukokuseki akushon films brought yakuza stories up to date, featuring individualistic heroes who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes in film noir-esque chiarsoscuro lighting. The early mukokuseki akushon films were often photographed in monochrome, something which enhanced their similarities with American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s – and European films noir of the 1950s and 1960s too (including Jules Dassin’s Rififi, 1955, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le deuxieme souffle, 1966). Later examples of the mukokuseki akushon, however, were more frequently shot in colour, developing into mudo akushon (‘mood action’) and nyu akushon (‘new action’) films; these two forms were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were even more morally ambiguous than their predecessors. Eventually, in the 1970s, these would be supplanted by jitsuroku pictures like Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series and the same director’s Street Mobster (1971), which is usually cited as one of the first examples of jitsuroko cinema. These jitsuroku films could be likened to the semidocumentary films noir such as Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street (1945), employing documentary-style camerawork and abrupt editing rhythms alongside storylines which more often than not were based in true accounts of life within the yakuza (or, at the very least, were claimed to be based on such accounts).

Kate Taylor-Jones has highlighted the fact that, along with many other examples of Jitsoruko, including the Battles Without Honor and Humanity films, Cops Vs Thugs takes as its setting the decades following the Second World War. In doing so, the films depict ‘the post-war Japanese economic drive […] as resulting in a situation where commercial business, yakuza, police and government officials are all equally destructive’ (Taylor-Jones, 2013: 62). The films depict post-war Japan as a dog-eat-dog world in which social turmoil ferments and resentment between different social groups accumulates.  Cops Vs Thugs features two groups, each including a pairing of a yakuza with a corrupt figure of authority: the Kawade group is trying to force its way into territories controlled by the Ohara gang; Kawade’s opposite number is Hirotani, who is acting boss of the Ohara hang in the absence of the imprisoned Ohara. Kawade is aided by corrupt government official Tomayasu, former head of the Tomayasu clan who presumably disbanded his organisation so that he may enter into politics. Tomayasu is, the film suggests, Kawade’s former mentor; in an early sequence, Tomayasu is shown in a hostess club, introducing Kawade to the mayor: ‘This blockhead is Kawade’, Tomayasu tells the mayor, ‘He learnt all about the business from me’. (Later, Tomayasu also suggests he ‘taught [Hirotani] everything about living in the underworld from the time he was wetting his bed’; in response to this, Hirotani reminds Tomayasu that he betrayed Boss Ohara when he disbanded the Tomayasu family: ‘I won’t attack an assemblyman, but watch out for accidents’, Hirotani warns Tomayasu.) Hirotani, meanwhile, is aided by corrupt cop Kuno. In this context, the film’s title (‘Cops Vs Thugs’) is mildly misrepresentative: a more accurate title might be ‘Cops and Thugs Vs Government and Thugs’. Cops Vs Thugs features two groups, each including a pairing of a yakuza with a corrupt figure of authority: the Kawade group is trying to force its way into territories controlled by the Ohara gang; Kawade’s opposite number is Hirotani, who is acting boss of the Ohara hang in the absence of the imprisoned Ohara. Kawade is aided by corrupt government official Tomayasu, former head of the Tomayasu clan who presumably disbanded his organisation so that he may enter into politics. Tomayasu is, the film suggests, Kawade’s former mentor; in an early sequence, Tomayasu is shown in a hostess club, introducing Kawade to the mayor: ‘This blockhead is Kawade’, Tomayasu tells the mayor, ‘He learnt all about the business from me’. (Later, Tomayasu also suggests he ‘taught [Hirotani] everything about living in the underworld from the time he was wetting his bed’; in response to this, Hirotani reminds Tomayasu that he betrayed Boss Ohara when he disbanded the Tomayasu family: ‘I won’t attack an assemblyman, but watch out for accidents’, Hirotani warns Tomayasu.) Hirotani, meanwhile, is aided by corrupt cop Kuno. In this context, the film’s title (‘Cops Vs Thugs’) is mildly misrepresentative: a more accurate title might be ‘Cops and Thugs Vs Government and Thugs’.

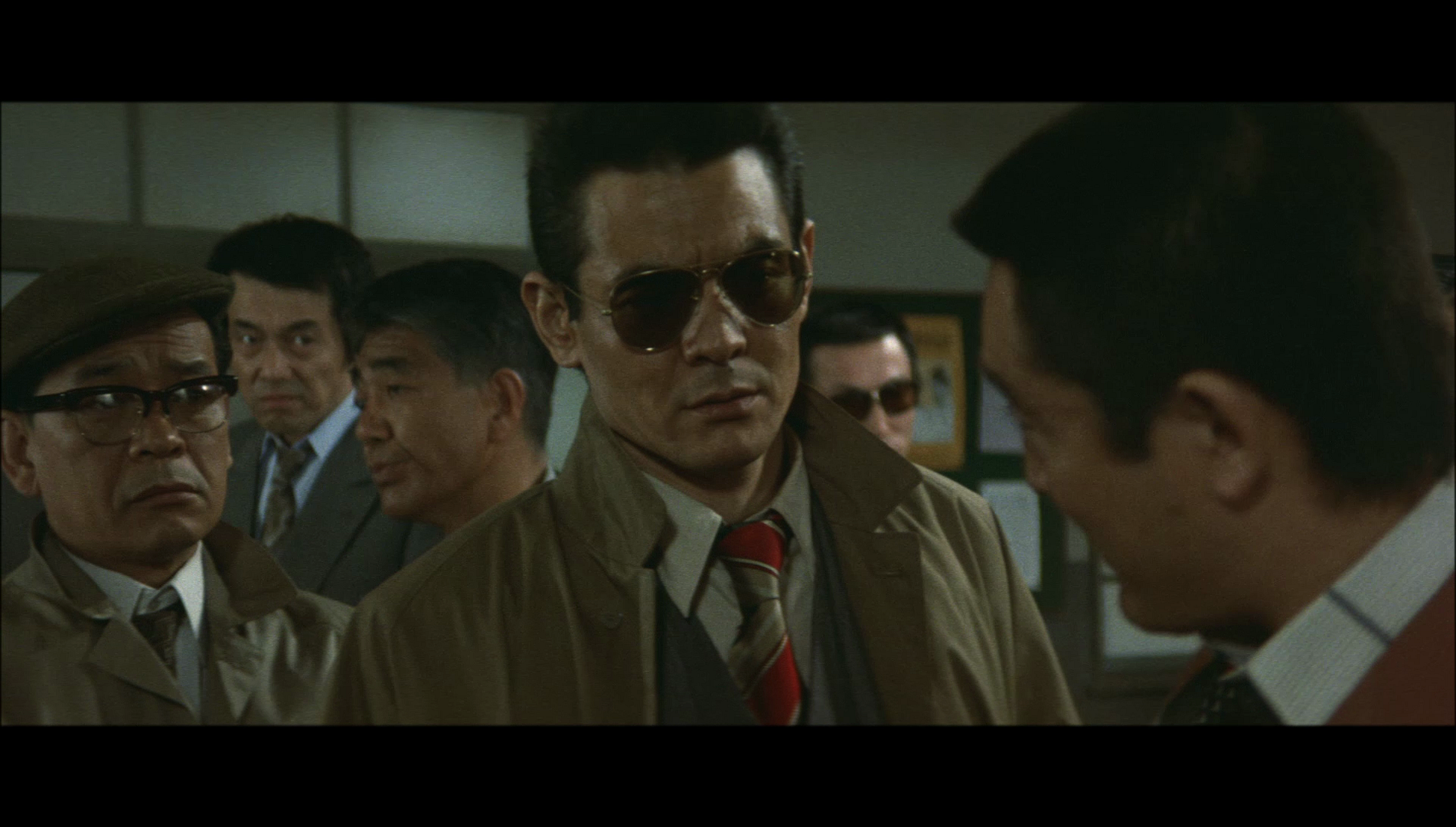

The film continuously erodes the distinction between the ‘cops’ and the ‘thugs’, suggesting that one may often be mistaken for another. The police are unable or unwilling to take action against the yakuza, who supply them with food and drink in exchange for a lack of interference in their affairs. The ties between the police and the yakuza run deep. Following Hirotani’s clan’s assault on one of Kawade’s clubs, Hirotani hands over one of his underlings and suggests the violence was simply as a result of this particular underling’s obsession with a hostess, Mariko, who had switched allegiances to work as a hostess for Kawade. ‘Who’d believe that story?’, a disbelieving Chief Ikeda asks. ‘Chief, if this is a war, we’d have to report it to headquarters’, Kuno says, ‘and they’d find out about the old Miyake incidents too. That’ll put you in a spot’. Later, when Hirotani hands over one of his low-ranking yakuza to the police, framing the boy for the attack on the club, the young yakuza wets his pants during interrogation. ‘You’d be better off working as a clerk at city hall’, Kuno tells the young yakuza dryly, underscoring the interchangeability of yakuza with employees of the municipality. In another sequence, two old friends – Kawamoto, a police officer, and Tsukahara, a yakuza – bump into one another and are surprised to discover that each is on the opposite side of the law. Kuno, Kawamoto and some other detectives go drinking with Hirotani, Tsukahara and other members of the Ohara family. ‘Cops and yakuza are the same’, one of the men says during this sojourn, ‘We’re the dropouts who couldn’t get good jobs’.  From the outset, Kuno is depicted as a Westernised cop in the mould of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry. In the film’s opening sequence, Kuno, wearing the sunglasses that dominate his face until the latter half of the film (when, presumably not by coincidence, the character begins to show increasing vulnerability and self-doubt), challenges a group of street thugs who steal food from a street vendor. The street thugs first mistake Kuno for a yakuza, introducing the film’s suggestion that the police and yakuza are indistinguishable in their attitudes, methods and even their appearance. The hoodlums ask Kuno ‘Are you one of Kawade’s men?’ However, Kuno sets them straight, revealing his status as a police officer. He humiliates the street thugs by slapping them across the face (‘Looks like you’re itching for a beating’, he declares), asserting that he knows they are planning something big but tells them that he is disinterested in preventing them from heading to their certain deaths in a turf war, before warning them not to commit petty theft. From the outset, Kuno is depicted as a Westernised cop in the mould of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry. In the film’s opening sequence, Kuno, wearing the sunglasses that dominate his face until the latter half of the film (when, presumably not by coincidence, the character begins to show increasing vulnerability and self-doubt), challenges a group of street thugs who steal food from a street vendor. The street thugs first mistake Kuno for a yakuza, introducing the film’s suggestion that the police and yakuza are indistinguishable in their attitudes, methods and even their appearance. The hoodlums ask Kuno ‘Are you one of Kawade’s men?’ However, Kuno sets them straight, revealing his status as a police officer. He humiliates the street thugs by slapping them across the face (‘Looks like you’re itching for a beating’, he declares), asserting that he knows they are planning something big but tells them that he is disinterested in preventing them from heading to their certain deaths in a turf war, before warning them not to commit petty theft.

For all intents and purposes, in terms of how it outlines the methods and fearlessness of this ‘rogue’ cop, this opening sequence is strikingly similar to the opening sequence of Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971), in which Eastwood’s ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan displays a propensity for violence and calm under pressure when his lunchtime hot dog is interrupted by a necessity to intervene in an armed robbery. Callahan seems more concerned with the fact that his lunch has been interrupted than with the possibility that he may be killed by the shotgun-wielding robbers. Likewise, Kuno is unfazed by the street thugs’ promises of violence, the sequence building to Kuno’s blackly comic assertion that he’s uninterested in what the street thugs are planning – which will surely lead to their deaths, he reasons, which he sees no value in preventing – but he simply will not allow them to steal food from a street vendor. (‘But first, pay for your sushi. I won’t let you skip out on your restaurant bills’, Kuno asserts.)  As the story progresses and the drive to ‘clean up’ the police department gathers steam, Kuno is given a new nemesis: a ‘clean nose’ detective named Kaida (Umemiya Tatsuo). An expert in judo, Kaida has no time for members of the police force who fraternise with yakuza or accept gifts from them. ‘You have to bring yourself down to the yakuza’s level to control them’, Ikeda protests when Kaida attempts to enforce his rules amongst the detectives. Kaida’s idealism leads him to adopt uncompromising tactics, raiding Hirotani and thereby placing Kuno in potential danger: ‘There’s a way to handle the yakuza’, Kuno tells Kaida, ‘What if you sting them and someone gets hurt?’ Kaida’s manipulation of an informant leads to a brutal stabbing, and following this Kuno confronts Kaida directly, telling the officer that his actions were inhuman. ‘I know how their world works’, Kuno asserts, ‘People like you would never understand’. Ultimately, however, as the film reaches its climax, Kuno is forced to choose whether to side with Hirotani or to ally himself with Kaida’s methods. As the story progresses and the drive to ‘clean up’ the police department gathers steam, Kuno is given a new nemesis: a ‘clean nose’ detective named Kaida (Umemiya Tatsuo). An expert in judo, Kaida has no time for members of the police force who fraternise with yakuza or accept gifts from them. ‘You have to bring yourself down to the yakuza’s level to control them’, Ikeda protests when Kaida attempts to enforce his rules amongst the detectives. Kaida’s idealism leads him to adopt uncompromising tactics, raiding Hirotani and thereby placing Kuno in potential danger: ‘There’s a way to handle the yakuza’, Kuno tells Kaida, ‘What if you sting them and someone gets hurt?’ Kaida’s manipulation of an informant leads to a brutal stabbing, and following this Kuno confronts Kaida directly, telling the officer that his actions were inhuman. ‘I know how their world works’, Kuno asserts, ‘People like you would never understand’. Ultimately, however, as the film reaches its climax, Kuno is forced to choose whether to side with Hirotani or to ally himself with Kaida’s methods.

However, Kuno is a more complex character than this opening sequence might suggest. As the film progresses, Kuno is shown trying to encourage Hirotani to rein in his behaviour. In one sequence, in reference to the hostess Mariko, Hirotani comments sleazily, ‘I’d like to have her go down on me’, whilst stroking his crotch. Kuno gently chastises Hirotani for this. When Hirotani helps Kuno return to his home following their drunken night out with Kawamoto and Tsukahara, Kuno collapses in a heap on the floor after remembering the time he saved Hirotani from being arrested for the murder of Boss Miyake. ‘A man who can’t help people has no right to judge others’, Kuno asserts. As Kuno passes out, Hirotani looks at a photography of a woman and child – Kuno’s wife and son, from whom Kuno is separated. Later in the film, Kuno is confronted at work by his wife, who demands a divorce that Kuno is unwilling to give her, humiliating Kuno in front of his colleagues by asserting loudly that ‘He’s [Kuno is] practically a yakuza puppet. He takes bribes and accepts drinks from them’.  Much is made of changing value systems amongst the yakuza, with the Kawade family – the film’s chief antagonists – representing a new, corporate and disloyal brand of organised crime. When the Hirotani family raid one of Kawade’s clubs, Kawade tells the police that the raiders ‘were Hirotani’s men’. Kuno observes, ‘Yakuza have changed. They wouldn’t have dared mention their raiders’ names in the old days’. The Kawade clan are dope peddlers, Kuno accusing Kawade of selling dope for ‘the Shinmei mob’ on Ohara territory. Meanwhile, the Ohara clan wait for the return of Boss Ohara, who has spent a significant period of time in jail. Hirotani’s struggles with Kawade are a matter of honour based on Hirotani’s promise to Boss Ohara that he will look after his territories: Hirotani tells Kuno that Ohara ‘will be released soon. I have to take care of his turf. I promised him I’d do that’. However, when he returns, Ohara is accompanied by his cellmate and new ‘sworn brother’ Komiya; now a broken man, Ohara weeps openly, revealing himself to have been softened by his time in prison. Ohara has also become incredibly devout in his religious beliefs, something which is facilitated by Komiya’s presence. Frustrated at Ohara’s new behaviours, Hirotani and another yakuza joke about ‘the boss lay[ing] a guy like [Komiya] in prison’. The ‘new’ Ohara is an easy target for Kawade and his associates, and is eventually persuaded by Tomayasu to disband the Ohara gang, handing the Ohara clan’s affairs over to Kawade and leading to Hirotani’s desperate actions at the climax. As with many examples of the jitsuroku, Cops Vs Thugs ultimately depicts an inter-generational conflict, with the older figures of authority manipulating the futures of their younger, Westernised counterparts, leading all of the characters to a final, desperate confrontation. Much is made of changing value systems amongst the yakuza, with the Kawade family – the film’s chief antagonists – representing a new, corporate and disloyal brand of organised crime. When the Hirotani family raid one of Kawade’s clubs, Kawade tells the police that the raiders ‘were Hirotani’s men’. Kuno observes, ‘Yakuza have changed. They wouldn’t have dared mention their raiders’ names in the old days’. The Kawade clan are dope peddlers, Kuno accusing Kawade of selling dope for ‘the Shinmei mob’ on Ohara territory. Meanwhile, the Ohara clan wait for the return of Boss Ohara, who has spent a significant period of time in jail. Hirotani’s struggles with Kawade are a matter of honour based on Hirotani’s promise to Boss Ohara that he will look after his territories: Hirotani tells Kuno that Ohara ‘will be released soon. I have to take care of his turf. I promised him I’d do that’. However, when he returns, Ohara is accompanied by his cellmate and new ‘sworn brother’ Komiya; now a broken man, Ohara weeps openly, revealing himself to have been softened by his time in prison. Ohara has also become incredibly devout in his religious beliefs, something which is facilitated by Komiya’s presence. Frustrated at Ohara’s new behaviours, Hirotani and another yakuza joke about ‘the boss lay[ing] a guy like [Komiya] in prison’. The ‘new’ Ohara is an easy target for Kawade and his associates, and is eventually persuaded by Tomayasu to disband the Ohara gang, handing the Ohara clan’s affairs over to Kawade and leading to Hirotani’s desperate actions at the climax. As with many examples of the jitsuroku, Cops Vs Thugs ultimately depicts an inter-generational conflict, with the older figures of authority manipulating the futures of their younger, Westernised counterparts, leading all of the characters to a final, desperate confrontation.

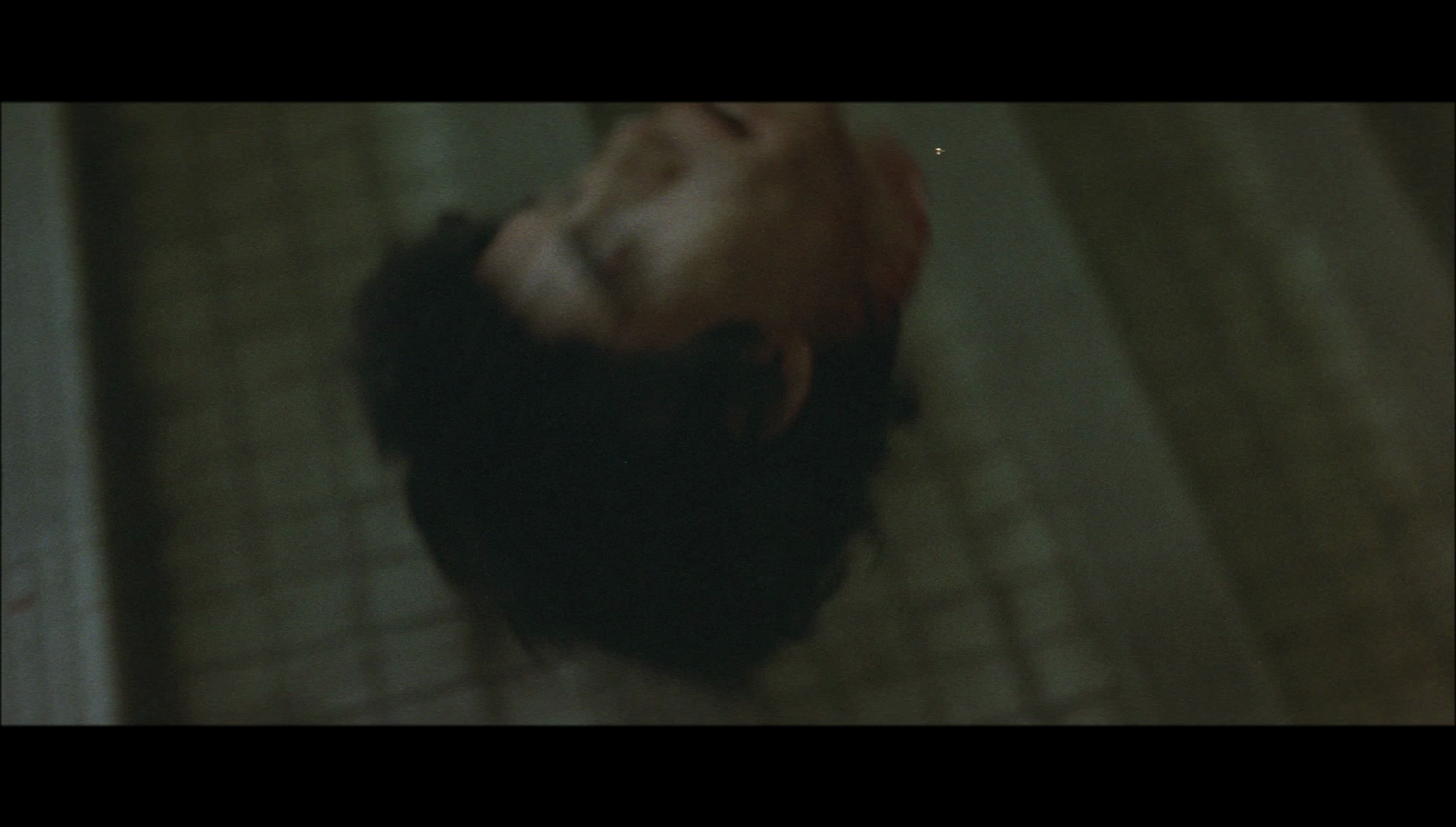

The film uses some sophisticated techniques, including mixing colour and monochrome photography, employing a roving semidocumentary style of photography, and the incorporation of both still photography (depicted via a montage) and newspaper headlines. The opening titles sequence features newspaper headlines summarising the events in Kurashima City which have led to the current set of circumstances: Boss Miyake’s murder in 1957 (later revealed to have been committed by Hirotani), the arrest of Boss Ohara in 1958, and the disbanding of the Tomayasu faction in 1960 and election of Tomayasu to local government in 1962. The film also makes counterpunctive use of music: one particularly memorable sequence features a brutal killing which takes place to the aural accompaniment of a children’s lullaby that is playing on a television set. As in any number of Japanese films of this period, there are also some visual allusions to Japanese experimental photography of the kind found in the pages of the short-lived but groundbreaking experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70). These sophisticated techniques are offset by the film’s frequently deeply earthy content.

Video

The film takes up approximately 23Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 100:37 mins. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Most of the film was shot on 35mm colour stock. However, as noted above, the film features some footage – a flashback depicting the night that Kuno saved Hirotani from being arrested for the murder of Boss Miyake – shot in high contrast monochrome, on film stock that seems to have been ‘pushed’, emphasising the contrast and the grain structure. This sequence has the look of the are, bure, boke (‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’) style in Japanese photography, most often associated with the likes of Moriyama Daido and Takanashi Yutaka and found in the pages of the experimental photography magazine Purovōku/Provoke. Fukasaku uses a roving camera and a semidocumentary approach to the photography. Zoom lenses and telephoto lenses are used throughout the film to convey a sense of surveillance and create a sense of claustrophobia within the interiors, compressing space and making it seem smaller. The result is a film with a very coarse aesthetic, the anamorphic lenses used in Japanese productions of the period often seeming very sharp in the centre but tapering off to softness at the periphery. This is compounded by the fact that the production seems to have featured quite heavy use of zoom lenses and telephoto lenses. The film takes up approximately 23Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 100:37 mins. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Most of the film was shot on 35mm colour stock. However, as noted above, the film features some footage – a flashback depicting the night that Kuno saved Hirotani from being arrested for the murder of Boss Miyake – shot in high contrast monochrome, on film stock that seems to have been ‘pushed’, emphasising the contrast and the grain structure. This sequence has the look of the are, bure, boke (‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’) style in Japanese photography, most often associated with the likes of Moriyama Daido and Takanashi Yutaka and found in the pages of the experimental photography magazine Purovōku/Provoke. Fukasaku uses a roving camera and a semidocumentary approach to the photography. Zoom lenses and telephoto lenses are used throughout the film to convey a sense of surveillance and create a sense of claustrophobia within the interiors, compressing space and making it seem smaller. The result is a film with a very coarse aesthetic, the anamorphic lenses used in Japanese productions of the period often seeming very sharp in the centre but tapering off to softness at the periphery. This is compounded by the fact that the production seems to have featured quite heavy use of zoom lenses and telephoto lenses.

Nevertheless, regardless of how rough-around-the-edges the original photography was (entirely in keeping with the aesthetic of the jitsuroku pictures generally), Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation is very pleasing. The level of detail throughout the presentation is rich, and the structure of 35mm film is retained by both the transfer and the solid encode to disc. Contrast levels are equally good: defined midtones and balanced highlights are present, though blacks sometimes seem a little ‘crushed’. The colour palette seems true to source, featuring the muddy colour tones of 1970s street gangster films; it’s a gritty, grimy aesthetic. No distracting damage is present, and there is no evidence of harmful digital tinkering.

Audio

Audio is presented via LPCM 2.0 stereo track, with optional English subtitles. The audio track is fine: it is clean and clear throughout. The subtitles are easy to read and free from glaring errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Beyond the Film: Cops Vs Thugs’ (9:13). In a new introduction to the film, Fukasaku’s biographer Yamane Sadao reflects on Cops Vs Thugs in the context of Fukasaku’s other films. Yamane discusses the origins of the script in the research conducted by scriptwriter Kasahara Kazuo, and its relationship with the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series. The interview is in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - ‘All Under the Gun’ (13:38). Tom Mes, in a new video essay, discusses the relationships between police and yakuza throughout Fukasaku’s body of work. Mes discusses some of the visual symbolism in the films and the casting, and he reflects on the films’ commentary on post-war Japanese society. - Behind the scenes footage (4:59). This footage, shot on set during the making of Cops Vs Thugs, provides the viewer with the opportunity to see Fukasaku in action. Fukasaku is interviewed about the film’s themes and the use of violence in his films, and a glimpse is offered of Fukasaku directing the interrogation scene. - Trailer (3:16).

Overall

An excellent film, often cited as one of the best jitsuroku pictures, Cops Vs Thugs complements Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series perfectly; this is not surprising as the script has its origins in the research writer Kasahara conducted for the Battles Without Honor and Humanity films. Like Fukasaku’s other films, Cops Vs Thugs is both sophisticated and earthy, offering a cynical look at both the yakuza and wider society. Any fan of 1970s Japanese cinema who hasn’t seen this picture will want to snap it up straight away: it’s essential viewing. An excellent film, often cited as one of the best jitsuroku pictures, Cops Vs Thugs complements Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series perfectly; this is not surprising as the script has its origins in the research writer Kasahara conducted for the Battles Without Honor and Humanity films. Like Fukasaku’s other films, Cops Vs Thugs is both sophisticated and earthy, offering a cynical look at both the yakuza and wider society. Any fan of 1970s Japanese cinema who hasn’t seen this picture will want to snap it up straight away: it’s essential viewing.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation is very good, as pleasing as their other releases of Fukasaku pictures. The presentation is solid, and the contextual material is equally good. This is a tip-top release of an essential film. References: Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Taylor-Jones, Kate E (2013): Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. London: Wallflower Press

|

|||||

|