|

|

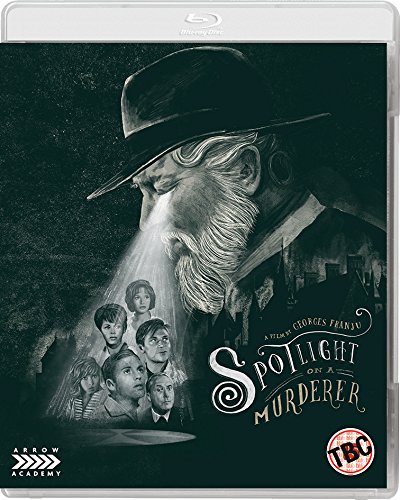

Spotlight on a Murderer AKA Pleins feux sur l'assassin (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th June 2017). |

|

The Film

Pleins feux sur l’assassin (Spotlight on a Murderer, Georges Franju, 1961) Pleins feux sur l’assassin (Spotlight on a Murderer, Georges Franju, 1961)

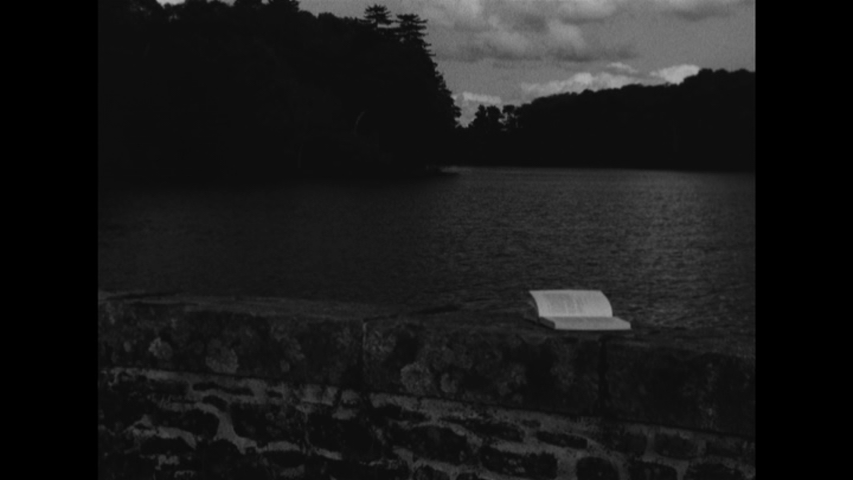

Although Georges Franju only directed eight feature-length films, beginning with the stark La tête contre les murs (The Keepers, 1959) and ending with Nuits rouges (Shadowman, 1974), his impact on French cinema was significant. Despite this, however, Franju’s films remain difficult to see, his career perhaps overshadowed by the international popularity of his second feature, Les yeux sans visage (Eyes Without a Face, 1960). Franju’s films teased surrealistic imagery out of naturalistic settings, their hints of the fantastical butting up against Franju’s experience as a documentary filmmaker. Franju’s third feature film, Spotlight on a Murderer is based on a novel by the masters of mid-20th Century French crime fiction, Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. Franju had previously collaborated with the pair on Eyes Without a Face, a project for which the team of Boileau and Narcejac had adapted the source novel by Jean Redon. Spotlight on a Murderer displays the same droll humour as the most famous adaptations of novels by Boileau-Narcejac, Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les diaboliques (1955). The premise of Spotlight on a Murderer has more than a hint of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (1939) to it, a group of people gathered in an isolated location falling victim to a mysterious killer.  The film begins with Count Herve de Kerloguen (Pierre Brasseur), dressed in the robes of a Knight of Malta, wandering the rooms of his lakeside castle. He enters a room hidden behind a mirror and, seating himself in a chair, cradles a clockwork doll; the Count sighs before expiring. The film begins with Count Herve de Kerloguen (Pierre Brasseur), dressed in the robes of a Knight of Malta, wandering the rooms of his lakeside castle. He enters a room hidden behind a mirror and, seating himself in a chair, cradles a clockwork doll; the Count sighs before expiring.

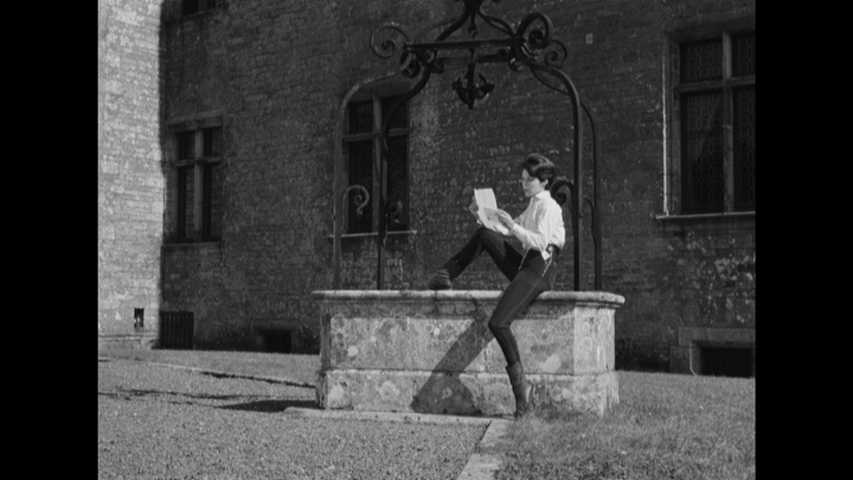

Medical student Jean-Marie de Kerloguen (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is being driven by his lover Micheline (Dany Saval) to the castle of his uncle, the Count. Parting ways with Micheline, who he promises to meet outside the castle during the evening, Jean-Marie enters his uncle’s home and takes his place amongst his family members, including his sister Jeanne (Pascale Audret) and her husband Claude (Georges Rollin), and Jean-Marie’s cousins Christian (Jean Babilee) and Edwige (Marianne Koch), the latter of whom has come from Germany. Together, the Count’s relations are told that their uncle, the Count, has vanished, though the desperate state of his health means that he is ‘unquestionably deceased’. The notary (Robert Vattier) tells the gathered family members that ‘If the body [of the Count] is not found, you cannot claim your inheritance for five years after the date of presumed death’. Reminded that for the period of five years, or until the Count’s body is discovered, they must ‘maintain this house, pay all the taxes’, Jean-Marie and the others attempt to come up with methods by which they can use the castle to generate income, making the domicile self-sustainable. Meeting with Micheline secretly at night, Jean-Marie tells her of the legend that surrounds the castle: in the 15th Century, one of his ancestors, a Count, was cuckolded by his wife, Éliane. One day, the Count returned from a hunting expedition to find Éliane in the arms of her lover. The Count slew his wife’s lover in a duel with swords, and Éliane threw herself from the tower in an act of suicide. Micheline reasons that if the castle were hers, she would organise a son et lumière show focusing on the legend; the revenue from such a show would help sustain the castle. Jean-Marie agrees and proposes this idea to his relatives. Working together, they swiftly make preparations for such a show, including fitting a public address system throughout the castle and installing a central control desk to manipulate the lights and sounds necessary for the show. However, one of the cousins, Henri (Gerard Buhr), is electrocuted when, whilst he is attempting to repair one of the projectors, somebody turns the power back on.  Meanwhile, Jeanne is conducting an affair with André (Philippe Leroy). Claude is made aware of this affair when a mysterious voice announces over the public address system that Jeanne is in her chambers with André. Interrupting the lovers, Claude kills André and is arrested. Jeanne looks set to re-enact the fate of Éliane, whilst the high tech monitoring devices the cousins have installed in the castle suggest the presence of an unknown person – perhaps a ghost. Meanwhile, Jeanne is conducting an affair with André (Philippe Leroy). Claude is made aware of this affair when a mysterious voice announces over the public address system that Jeanne is in her chambers with André. Interrupting the lovers, Claude kills André and is arrested. Jeanne looks set to re-enact the fate of Éliane, whilst the high tech monitoring devices the cousins have installed in the castle suggest the presence of an unknown person – perhaps a ghost.

The opening sequence of Spotlight on a Murderer deftly sketches Jean-Marie and Micheline’s status as a modern couple. Traveling from Paris, where he is studying medicine, Jean-Marie is a passenger in a car being driven by Micheline. Micheline is a modern, metropolitan young woman; she complains about the isolated location of the Count’s castle (‘I hope there’s a cinema in this godforsaken place’, she tells Jean-Marie) and is put-out by Jean-Marie’s refusal to introduce her to his family – motivated, we are led to believe, by Jean-Marie’s embarrassment at Micheline, who is cosmopolitan in her worldview and presumably of a lower standing in the social hierarchy. As they near the castle, Micheline stops the car; Jean-Marie heads behind a large rock, carrying a suitcase. He returns a few moments later, dressed in mourning clothes. The action is symbolic: Jean-Marie is shucking off the trappings of the modern world, his girlfriend and his clothes, before arriving at the Count’s castle – a place which symbolises the past. Spotlight on a Murderer juxtaposes the past with the present, the legend of Éliane and her suicide being doubled within the narrative by Jeanne’s betrayal of her husband Claude. Via its depiction of a past sin doomed to repeat itself, Franju’s film conveys a sense of fatalism – the castle becoming rather like the mansion in Mario Bava’s Lisa e il diavolo (Lisa and the Devil, 1973), in which the inhabitants become trapped in a never-ending loop of repeated behaviour. The son et lumière show is an attempt to package this past and commodify it, turning it into a ‘product’ that can then be used to produce wealth. Christian, the unemployed ‘suffering artist’ amongst Jean-Marie’s cousins, is tasked with writing the script for the show. He produces a script that focuses on the legend, suggesting that the family name (Kerloguen) is shared by the lake near to the castle and means ‘creature from the deep’. However, he’s reminded by Henri that this is nonsense; Christian reasons that those attending the son et lumière show won’t know that this is a fabrication – and the subtle lie will make the show more entertaining for them. ‘Tourists want medieval stuff. Pomp and heraldry’, Christian asserts. ‘Oh, come on. The crime and the cuckold. That’s what they’re interested in. Nothing else’, Henri responds. With this exchange, the film demonstrates a strong sense of reflexivity, the dialogue between Henri and Christian echoing the film’s own juxtaposition of a legend which trades in ‘medieval stuff. Pomp and heraldry’ and a present-day story filled with intrigue and sex (‘The crime and the cuckold’). (Aside from Jeanne’s affair with André, the film also shows Edwige attempting to seduce the groom of the stables, Yvan; returning from a night ride on one of the horses, Edwige demands that Yvan remove her boots, which she says are sticking to her legs and feet. Yvan kneels before Edwige and removes her boots, but she places her bare foot on his thigh, close to his crotch. It’s quite a daring scene, bold in its suggestion of Edwige’s sexual frankness.)  Furthering the juxtaposition of the past with the present, as the son et lumière show that Micheline proposes is put in place by the surviving members of the family, the ancient castle becomes decked out with mod cons, including an ultra-modern public address system which is connected to a central switchboard that, via flashing lights on a control panel, can track the movement of guests through the various sectors of the building. Following Claude’s murder of Jeanne’s lover, and Claude’s incarceration, this public address system is used to torment Jeanne. ‘I can see you’, a mysterious voice declares over the public address system, ‘It’s because of you that André is dead. You’re guilty, Jeanne; you’re guilty’. Likewise, when the relatives gather round the switchboard and see the flashing lights indicating the presence of someone moving through the seemingly empty rooms, Jean-Marie’s cousins are quick to take this as evidence of a ghostly presence within the castle. The film seems to suggest that modern technologies, combined with the symbolic importance of the castle (as something which represents the past and its associated legends), may be manipulated to convince people that they are experiencing supernatural events or being visited by ethereal presences. (In this sense, it’s the opposite of today’s horror films, where high technology is used to detect ‘genuine’ supernatural presences.) Furthering the juxtaposition of the past with the present, as the son et lumière show that Micheline proposes is put in place by the surviving members of the family, the ancient castle becomes decked out with mod cons, including an ultra-modern public address system which is connected to a central switchboard that, via flashing lights on a control panel, can track the movement of guests through the various sectors of the building. Following Claude’s murder of Jeanne’s lover, and Claude’s incarceration, this public address system is used to torment Jeanne. ‘I can see you’, a mysterious voice declares over the public address system, ‘It’s because of you that André is dead. You’re guilty, Jeanne; you’re guilty’. Likewise, when the relatives gather round the switchboard and see the flashing lights indicating the presence of someone moving through the seemingly empty rooms, Jean-Marie’s cousins are quick to take this as evidence of a ghostly presence within the castle. The film seems to suggest that modern technologies, combined with the symbolic importance of the castle (as something which represents the past and its associated legends), may be manipulated to convince people that they are experiencing supernatural events or being visited by ethereal presences. (In this sense, it’s the opposite of today’s horror films, where high technology is used to detect ‘genuine’ supernatural presences.)

Via its depiction of greed amongst the mourners, the desire to eliminate or minimise competition for the Count’s estate being the primary motivation for the murders, the film also suggests very strongly that wealth has a corruptive effect on human relationships. The ‘problem’ arises because the relatives are cognisant of the fact that the Count, owing to his unspecified medical condition, is dead, but that his body cannot be found: ‘Medically, he is dead’, the notary tells them, ‘But legally, he is missing’. Jean-Marie acknowledges the extent to which the money (or rather, the promise of it) has placed the Count’s surviving relatives at one another’s throats. ‘All this fortune at hand, it’s enough to make anyone insane’, Jean-Marie says, ‘We watch each other as if we don’t have the same interest. We used to be friends. This whole castle, to us. Now we don’t even know each other’. Micheline attempts to persuade Jean-Marie to abandon the castle and the promise of inheriting his uncle’s wealth, suggesting that the reason why Jean-Marie is so reluctant to introduce her to his family may be different to what she believed: ‘Is it that you don’t want me to meet your family, or your family that you don’t want to meet me?’, she asks.

Video

Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were provided with a check disc of the DVD included in this release only. On the DVD with which we were provided for review, Spotlight on a Murderer has a running time of 92:34 mins (PAL). The film is presented in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio. Though some compositions seem 'loose', suggesting the film may have been shot with the intention of it being exhibited in cinemas at 1.66:1, the majority of the compositions seem very well-balanced at 1.37:1. The 35mm monochrome photography is represented excellently, with midtones exhibiting strong definition and deep shadows in place. Highlights are balanced too. Plenty of detail is present throughout the film, with little to no damage being exhibited within the source material. It’s a very good presentation that displays no overt evidence of digital tinkering.

Audio

On the DVD provided for review, audio is delivered via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track, in French, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles. The audio track is audible throughout, with no issues, distortion or damage. The subtitles are easy to read and free from errors, translating the dialogue as accurately as possible.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Le Courrier du cinéma (27:12). Made for broadcast on French television, this instalment of the French magazine series Le Courrier du cinéma focuses on the production of Spotlight on a Murderer features input from Franju, Trintignant, Audret, Brasseur, Koch and Saval. The participants are interviewed, with Franju elaborating on the differences between this picture and Eyes Without a Face (which he describes as a ‘terror’ film – making the distinction between a cinema of ‘terror’ and one of ‘horror’). This film, Franju suggests, is about the characters revealing their true nature in their quest to get access to the Count’s wealth. The interview with Koch is particularly warm, the actress revealing that she stumbled into acting almost by mistake and was originally on path to a career in medicine. The documentary is in French, with optional English subtitles. - The film’s trailer (3:33)

Overall

A delicious black comedy that looks sideways at the tropes of ‘old dark house’ pictures such as the various film adaptations of John Willard’s play The Cat and the Canary, in its satirical examination of the paradigms of this popular narrative paradigm Spotlight on a Murderer has some interesting similarities with a British black comedy released in the same year, Pat Jackson’s What a Carve Up! (1961), which was based on the Frank King novel The Ghoul (1928). On top of its blackly comic approach, Spotlight on a Murderer features Franju’s characteristic suggestion of the intrusion of the fantastical into a very realistic context; the use of technology to conjure, or suggest, the supernatural might invite in viewers comparisons with later pictures such as Pupi Avati’s Zeder (1983), with its use of surveillance technology at the climax, and perhaps even Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (Peter Sasdy, 1972). Into this, Franju also weaves some recurring symbolic imagery involving birds – something which is a bit of a leitmotif within Franju’s work. A delicious black comedy that looks sideways at the tropes of ‘old dark house’ pictures such as the various film adaptations of John Willard’s play The Cat and the Canary, in its satirical examination of the paradigms of this popular narrative paradigm Spotlight on a Murderer has some interesting similarities with a British black comedy released in the same year, Pat Jackson’s What a Carve Up! (1961), which was based on the Frank King novel The Ghoul (1928). On top of its blackly comic approach, Spotlight on a Murderer features Franju’s characteristic suggestion of the intrusion of the fantastical into a very realistic context; the use of technology to conjure, or suggest, the supernatural might invite in viewers comparisons with later pictures such as Pupi Avati’s Zeder (1983), with its use of surveillance technology at the climax, and perhaps even Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (Peter Sasdy, 1972). Into this, Franju also weaves some recurring symbolic imagery involving birds – something which is a bit of a leitmotif within Franju’s work.

Like many of Franju’s films, Spotlight on a Murderer has been notoriously difficult to see, so Arrow Academy’s new release is extremely welcome. On the DVD we were provided for review, the presentation of the main feature is very pleasing; one can only assume that the Blu-ray presentation, if true to source and playing to the strengths of the HD format, is even more impressive. Sadly, there’s not a great deal of contextual material, though the instalment of Le Courier du cinéma is an excellent inclusion. Some contextualisation of the film within Franju's body of work would have been very welcome, but regardless this is a superb release of a neglected film, and comes with a very strong recommendation.

|

|||||

|