|

|

Headshot (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th June 2017). |

|

The Film

Headshot (Kimo Stamboel & Timo Tjahjanto, 2016) Headshot (Kimo Stamboel & Timo Tjahjanto, 2016)

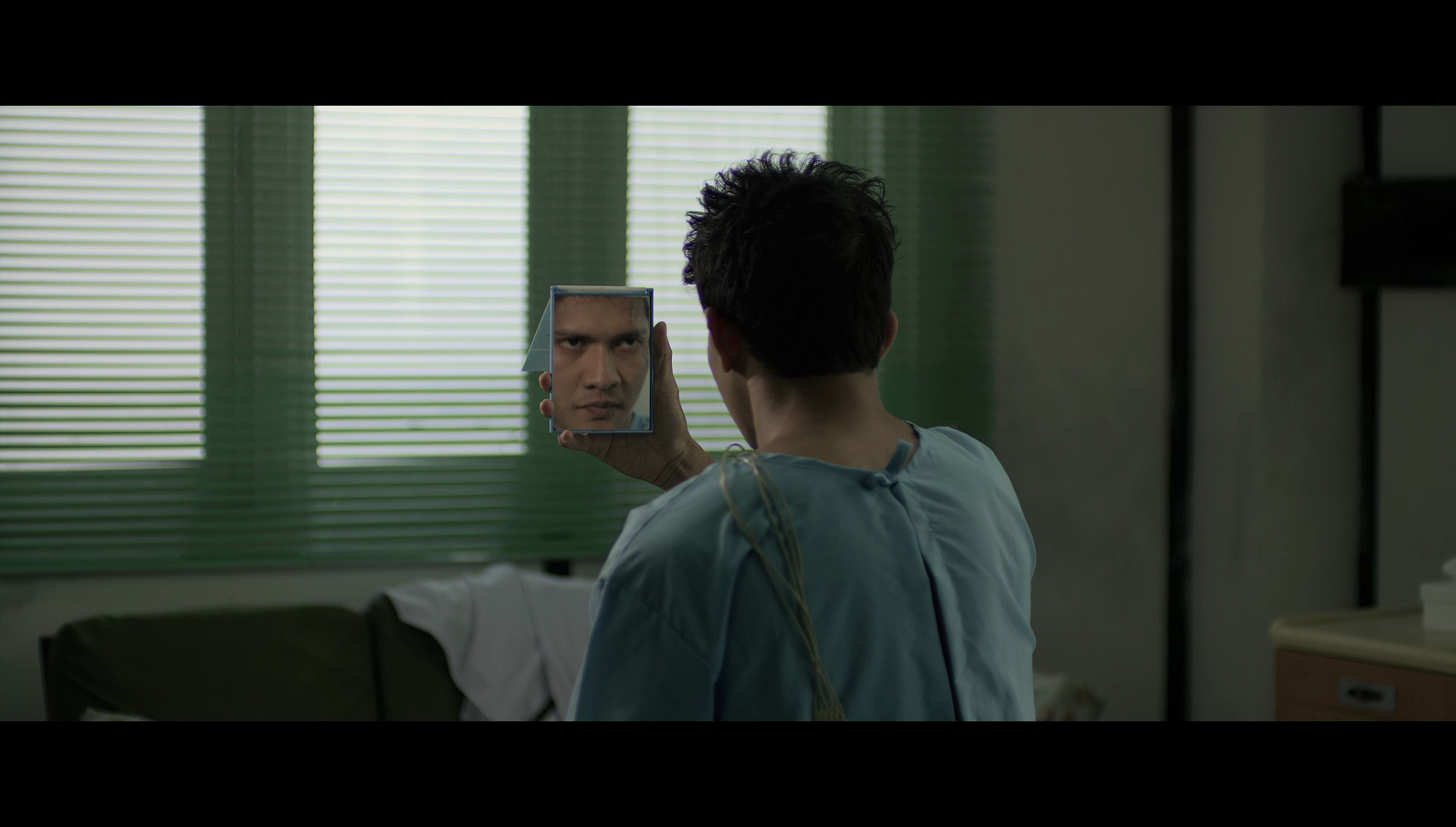

Indonesian writer-directors Kimo Stamboel and Timo Tjahjanto, often credited as ‘The Mo Brothers’ on the film on which they collaborate, began their filmmaking career with a short, ‘Dara’, in 2007. After directing a segment for the portmanteau horror picture Takut Faces of Fear in 2008, they collaborated on their first feature film, Macabre (also 2009). A horror film comparable to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), featuring a group of young people who find themselves trapped in an isolated house belonging to a family of killers, Macabre was an extension of their short film ‘Dara’. Their second feature film together, Killers (2014), was produced by Gareth Evans, and had a similar restless energy and forward momentum to Evans’ own The Raid (2011). In its fusion of high octane gunplay and brutal martial arts action, the international success of Evans’ The Raid invited comparisons with the heyday of Hong Kong’s ‘heroic bloodshed’ films, the picture having a similar kinetic energy to pictures like John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986) and Bullet in the Head (1990). Headshot, Stamboel and Tjahjanto’s third feature film, stars the leading actor from The Raid, Iko Uwais. Here, Uwais plays Ishmael, an amnesiac who is discovered on a beach by local man Romli (Yaya A W Unru). In a coma, Ishmael is cared for by junior doctor Ailin (Chelsea Islan). When Ishmael awakens from his coma, he takes his name from the narrator of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the novel that Ailin is reading.  Meanwhile, criminal kingpin Mr Lee (Sunny Pang) has escaped from a high security prison. Lee experiences a run-in with two underworld figures, who accuse Lee of selling them cheap Chinese guns and poor quality drugs. Lee kills one of the men, and the other man tells Lee that he has seen Ishmael at the hospital: ‘I heard he [Ishmael] was very close to you’, the man tells Lee. Meanwhile, criminal kingpin Mr Lee (Sunny Pang) has escaped from a high security prison. Lee experiences a run-in with two underworld figures, who accuse Lee of selling them cheap Chinese guns and poor quality drugs. Lee kills one of the men, and the other man tells Lee that he has seen Ishmael at the hospital: ‘I heard he [Ishmael] was very close to you’, the man tells Lee.

Under Lee’s orders, the man visits the hospital and threatens Ailin; but Ailin is saved by Ishmael. Ailin departs for Jakarta, asking Ishmael to accompany her; there, she reasons, the more experienced surgeons will be able to extract the bullet fragments that reside in Ishmael’s skull. Ishmael refuses, however, and Ailin boards the bus for Jakarta, where she must continue with her studies in medicine. However, the bus is attacked by Lee’s thugs; all of the passengers aboard it are massacred, except Ailin and a young girl, who Lee’s people abduct. Ailin manages to telephone Ishmael, and he arrives on the scene with Romli. Ishmael manages to kill a number of Lee’s assassins, but Romli is shot and dies. The police arrive and arrest Ishmael for the horrendous assault on the bus, believing Ishmael to have committed this violence. Ishmael remembers being shot in the head by a young woman, Rika (Julie Estelle). He also experiences memories of his childhood, of being trained in hand-to-hand combat and gunplay, and being trapped at the bottom of a dried-out well with other children where he was forced to fight to the death. During his interview with a detective (T Rifnu Wikana), Ishmael is told of his former relationship with Lee: Ishmael was a member of Lee’s gang of killers. Lee specialises in abducting children between the ages of 6 and 10 and, via a brutal regimen, training them to be ruthless assassins; Ishmael was one of those assassins, sitting at Lee’s right hand. However, Lee’s gang lay siege to the police station, and lee must survive in order to find Lee’s hideout and rescue Ailin. Along the way, Ishmael must fight to the death his former ‘brothers’ and ‘sister’, including the even-tempered but deadly Besi (Very Tri Yullsman) and the beautiful Rika (Julie Estelle), Ishmael’s former lover.  Like Clint Eastwood’s nameless protagonist in High Plains Drifter (1973) or, perhaps, Murphy (Peter Weller) in RoboCop (Paul Verhoeven, 1987), Ishmael essentially comes back from the dead to seek retribution for his ‘murder’ by Rika, acting under the orders of Lee. Like the protagonists of the two aforementioned films, throughout Headshot, at moments of stress or when he is struck, Ishmael experiences flashbacks to his former life, his ‘death’ at the hands of Rika depicted in short bursts of footage bathed in yellow or red. Ishmael’s amnesia has allowed him to break the fatalistic cycle of his life, giving him free will; forgetting has enabled him to escape his deterministic path (following Lee and doing his bidding). However, to finally break his ties with this ‘father from hell’, Ishmael must confront – and kill – his former brothers and sisters in servitude. However, in doing so Ishmael is faced with a dilemma about his own personality: is he a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ person, and does his previous behaviour impact on his beliefs and attitude in the present? ‘What if I’m not a good person?’, he asks Ailin after he has been released from hospital, ‘Would you still be there for me?’ ‘Ishmael, you’re not a bad person’, she responds. ‘That’s why I need to find out who I am’, Ishmael says. Like Clint Eastwood’s nameless protagonist in High Plains Drifter (1973) or, perhaps, Murphy (Peter Weller) in RoboCop (Paul Verhoeven, 1987), Ishmael essentially comes back from the dead to seek retribution for his ‘murder’ by Rika, acting under the orders of Lee. Like the protagonists of the two aforementioned films, throughout Headshot, at moments of stress or when he is struck, Ishmael experiences flashbacks to his former life, his ‘death’ at the hands of Rika depicted in short bursts of footage bathed in yellow or red. Ishmael’s amnesia has allowed him to break the fatalistic cycle of his life, giving him free will; forgetting has enabled him to escape his deterministic path (following Lee and doing his bidding). However, to finally break his ties with this ‘father from hell’, Ishmael must confront – and kill – his former brothers and sisters in servitude. However, in doing so Ishmael is faced with a dilemma about his own personality: is he a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ person, and does his previous behaviour impact on his beliefs and attitude in the present? ‘What if I’m not a good person?’, he asks Ailin after he has been released from hospital, ‘Would you still be there for me?’ ‘Ishmael, you’re not a bad person’, she responds. ‘That’s why I need to find out who I am’, Ishmael says.

Ishmael’s worst dreams are realised when he is caught by the police for the massacre on the bus, and the detective interviewing Ishmael tells him of Ishmael’s previous reputation as a ruthless killer: ‘There was once a rumour about a mysterious young man’, the detective says, ‘Each time he appeared, he left behind a massacre that turned the beach red with blood’. When Ishmael nears Lee’s hideout and finds the well in which, as a child, he was forced to fight others to the death over food and water, Ishmael’s memories begin to take shape and become more vivid, and he must confront the evil that Lee trained him to commit. ‘You remember it now?’, his ‘brother’ Besi asks Ishmael as he stands at the well, ‘All the memories from that fucking place [….] It’s what separates him from other scum. He taught us to survive and even kill [….] Yet it’s that very suffering that turned us into brothers’. Ishmael asks Besi how he can continue to fight and kill for Lee: ‘Everyone has to choose a side’, Besi replies, ‘Following that fucker is my fate’. Shortly afterwards, when he is forced to fight Rika, Ishmael reminds his former lover that she has free will: ‘You can get away’, he tells her, ‘You have the choice to be free’. However, Rika is unable to do this, Lee’s conditioning being so severe. Finally, Ishmael confronts Lee, telling him ‘I remember everything. You raised us to be wolves. ‘It was meant to make you all stronger’, Lee says by way of explanation. ‘You’re no longer a legend’, Ishmael asserts, ‘Just an old man who bullies little kids’. Lee’s response frames just how inhuman his ‘children’ have been trained to be: ‘You’re just a fucking dog that doesn’t know the meaning of “obey”’, Lee tells Ishmael.  The film contains a number of literary references. Most obviously, unaware of his true identity Ishmael acquires his name in reference to Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the novel that Ailin is reading when Ishmael awakens from his coma. (‘Call me Ishmael’ is the opening sentence of the novel.) In its depiction of a protagonist with amnesia who discovers a past life as a killer, Headshot might remind many viewers of Robert Ludlum’s novel 1980 novel The Bourne Identity (or its 1988 television movie adaptation, or the 2002 feature film adaptation). However, in Ishmael’s journey back through his past to confront the ‘father from hell’, to some extent Headshot recalls Marlow’s journey along the Congo to a confrontation with ‘Mistah Kurtz’ in Joseph Conrad’s novella 1899 Heart of Darkness (or Francis Ford Coppola’s loose 1979 film adaptation, Apocalypse Now). John Hyams’ recent ultraviolent action film Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (2012) similarly referenced Heart of Darkness in its narrative, with the film’s protagonist, amnesiac John (Scott Adkins) journeying along a violent path to a confrontation with UniSol Luc Devereaux (Jean-Claude Van Damme). The film contains a number of literary references. Most obviously, unaware of his true identity Ishmael acquires his name in reference to Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the novel that Ailin is reading when Ishmael awakens from his coma. (‘Call me Ishmael’ is the opening sentence of the novel.) In its depiction of a protagonist with amnesia who discovers a past life as a killer, Headshot might remind many viewers of Robert Ludlum’s novel 1980 novel The Bourne Identity (or its 1988 television movie adaptation, or the 2002 feature film adaptation). However, in Ishmael’s journey back through his past to confront the ‘father from hell’, to some extent Headshot recalls Marlow’s journey along the Congo to a confrontation with ‘Mistah Kurtz’ in Joseph Conrad’s novella 1899 Heart of Darkness (or Francis Ford Coppola’s loose 1979 film adaptation, Apocalypse Now). John Hyams’ recent ultraviolent action film Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (2012) similarly referenced Heart of Darkness in its narrative, with the film’s protagonist, amnesiac John (Scott Adkins) journeying along a violent path to a confrontation with UniSol Luc Devereaux (Jean-Claude Van Damme).

The film’s chief antagonist is Mr Lee, a deceptively softly-spoken man whose unobtrusive behaviour allows him to pass undetected amongst ‘straight’ society and leads to him being underestimated by his peers. When upon his escape from prison, Lee meets with the two underworld figures who criticise the guns and drugs that Lee has supplied them with, Lee approaches the ‘sit down’ with a carton of food. He calmly eats his meal with chopsticks, until the men accuse Lee of selling them cheap Chinese weapons and poor quality drugs. ‘I wanted to do business with you because of your reputation’, one of the men says, ‘Lee, the sea devil. Lee, the father from hell. You see, getting rid of you will give me a certain reputation too’. In response, Lee swiftly dispatches one of the men with a chopstick – which Lee buries into the man’s throat.  The depiction of Lee’s ‘children’, raised from childhood to do his bidding and willing to die for him, might be taken as a metaphor for today’s focus on radical Islamic militant groups and their use of suicide bombers; certainly, in the way in which these killers are brainwashed by Lee, acting as extensions of his will, and the manner in which they are framed as his ‘children’ (and Lee as the ‘father from hell’), there are echoes of Charles Manson’s ‘family’. The detective who interviews Ishmael tells him that the children Lee abducts ‘grew up. They were bred to become smugglers, plunderers and killers [….] Every one willing to die for their mysterious, terrorist master. Even amongst criminals he’s a terrifying figure’. The violence they commit his horrendous. Faces are pulverised, machetes fixed in bodies, people are impaled, a bullet is used to gouge out a man’s eye. The first taste of the violence Lee’s ‘children’ are capable of committing is when Lee is double-crossed by the two hoodlums, and we see Rika and Besi dispatch their various thugs. Shortly afterwards, Lee’s ‘children’ assault the bus on which Ailin is traveling to Jakarta, massacring everybody except Ailin and a young girl, who they abduct and return to Lee – presumably with the intention of making her one of their own. The bus sequence is one of the film’s standout setpieces; the other is in a police station, in which Ishmael confronts and fights his former ‘brothers’ – who are armed with machetes, shotguns, assault rifles and hand grenades, whilst Ishmael is handcuffed to a table. Strangely, the police station feels out of time and out of place, the walls a sickly green and the desks bedecked in rotary dial telephones and mechanical typewriters – objects that are strangely incongruous in a film in which the characters otherwise use smartphones with GPS software on them to track one another’s movements. The depiction of Lee’s ‘children’, raised from childhood to do his bidding and willing to die for him, might be taken as a metaphor for today’s focus on radical Islamic militant groups and their use of suicide bombers; certainly, in the way in which these killers are brainwashed by Lee, acting as extensions of his will, and the manner in which they are framed as his ‘children’ (and Lee as the ‘father from hell’), there are echoes of Charles Manson’s ‘family’. The detective who interviews Ishmael tells him that the children Lee abducts ‘grew up. They were bred to become smugglers, plunderers and killers [….] Every one willing to die for their mysterious, terrorist master. Even amongst criminals he’s a terrifying figure’. The violence they commit his horrendous. Faces are pulverised, machetes fixed in bodies, people are impaled, a bullet is used to gouge out a man’s eye. The first taste of the violence Lee’s ‘children’ are capable of committing is when Lee is double-crossed by the two hoodlums, and we see Rika and Besi dispatch their various thugs. Shortly afterwards, Lee’s ‘children’ assault the bus on which Ailin is traveling to Jakarta, massacring everybody except Ailin and a young girl, who they abduct and return to Lee – presumably with the intention of making her one of their own. The bus sequence is one of the film’s standout setpieces; the other is in a police station, in which Ishmael confronts and fights his former ‘brothers’ – who are armed with machetes, shotguns, assault rifles and hand grenades, whilst Ishmael is handcuffed to a table. Strangely, the police station feels out of time and out of place, the walls a sickly green and the desks bedecked in rotary dial telephones and mechanical typewriters – objects that are strangely incongruous in a film in which the characters otherwise use smartphones with GPS software on them to track one another’s movements.

Video

Taking up exactly 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, the presentation of Headshot is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 118:28 mins. Taking up exactly 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, the presentation of Headshot is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 118:28 mins.

Headshot was shot digitally, apparently on the RED Epic camera. The film’s colour palette is deliberately ‘plasticky’ and artificial at times, the opening sequence in which Lee escapes from prison bathed in orange and green light whose hue and saturation have quite obviously been boosted digitally. Lee’s flashbacks are given an almost sepia tint, the contrast seemingly boosted and a grain field employed to make these memories seem more like 35mm film. More naturalistic scenes are carefully balanced, however. This release, obviously, is a compressed digital clone of a digital source. As such, it’s characteristics are true to that source, other than the level of compression and the encode. The encode, for the record, is fine, bearing no problems at all. Throughout the presentation, there’s a strong level of fine detail present. Contrast is good, with balanced midtones and even highlights. Black seem a little ‘crushed’ at times, however, which is probably more a product of the lesser dynamic range of digital sensors as compared with film. (That said, the RED Epic reputedly has a 13.5 stop dynamic range, as compared with the 15-16 stop dynamic range of 35mm colour film.) In sum, it’s a pleasing presentation, a clone of a digital source that doesn’t betray any issues with compression or the encode to disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track, which contains a mixture of Indonesian and English dialogue. (Lee often speaks in English, whilst the other characters speak in Indonesian.) The Indonesian dialogue is accompanied by optional English subtitles, which are easy to read and free from errors. The audio track is rich and bassy, the music and sound effects filling the soundscape during the action sequences.

Extras

The sole ‘extras’ on the disc are two trailers, which play on disc start-up and are skippable: these trailers are for Battle Royale (1:51) and Audition (1:16).

Overall

Headshot is a film of incredibly brutal action, but on the other hand it contains some curious literary references (most obviously to Moby Dick, but also to Heart of Darkness). It’s an exciting, kinetic picture; watching it might remind a viewer of that glorious period during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Hong Kong’s ‘heroic bloodshed’ pictures were discovered by an international audience, before shaping the Hollywood action films of the 1990s and beyond. The combination of hand-to-hand combat and gunplay is handled superbly by the cast and crew, the action intense and beautifully orchestrated. Ishmael is a protagonist whose key dilemma is essentially an existential one: does he follow the fate prescribed for him by the ‘father from hell’ and, like Rika and Besi, sacrifice any potential for self-determination, or can he assert his free will. Ironically, in asserting his ability to free himself from the conditioning that has enslaved him, he is forced to use the violent methods that Lee instilled in him. The film offers a subtle questioning of the irony that lies in the necessity of using violence to quell violence but doesn’t make it its central focus (as, say, Clint Eastwood does in Unforgiven, 1992, or Sam Peckinpah in Straw Dogs, 1972). Fans of action films, especially those who enjoyed Killers, will find this to be a must-watch. Headshot is a film of incredibly brutal action, but on the other hand it contains some curious literary references (most obviously to Moby Dick, but also to Heart of Darkness). It’s an exciting, kinetic picture; watching it might remind a viewer of that glorious period during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Hong Kong’s ‘heroic bloodshed’ pictures were discovered by an international audience, before shaping the Hollywood action films of the 1990s and beyond. The combination of hand-to-hand combat and gunplay is handled superbly by the cast and crew, the action intense and beautifully orchestrated. Ishmael is a protagonist whose key dilemma is essentially an existential one: does he follow the fate prescribed for him by the ‘father from hell’ and, like Rika and Besi, sacrifice any potential for self-determination, or can he assert his free will. Ironically, in asserting his ability to free himself from the conditioning that has enslaved him, he is forced to use the violent methods that Lee instilled in him. The film offers a subtle questioning of the irony that lies in the necessity of using violence to quell violence but doesn’t make it its central focus (as, say, Clint Eastwood does in Unforgiven, 1992, or Sam Peckinpah in Straw Dogs, 1972). Fans of action films, especially those who enjoyed Killers, will find this to be a must-watch.

Arrow’s Blu-ray disc contains a solid presentation of the main feature but is sadly bereft of contextual material.

|

|||||

|