|

|

Doberman Cop AKA Doberuman deka AKA Detective Doberman (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th July 2017). |

|

The Film

Doberman Cop (Fukasaku Kinji, 1977) Doberman Cop (Fukasaku Kinji, 1977)

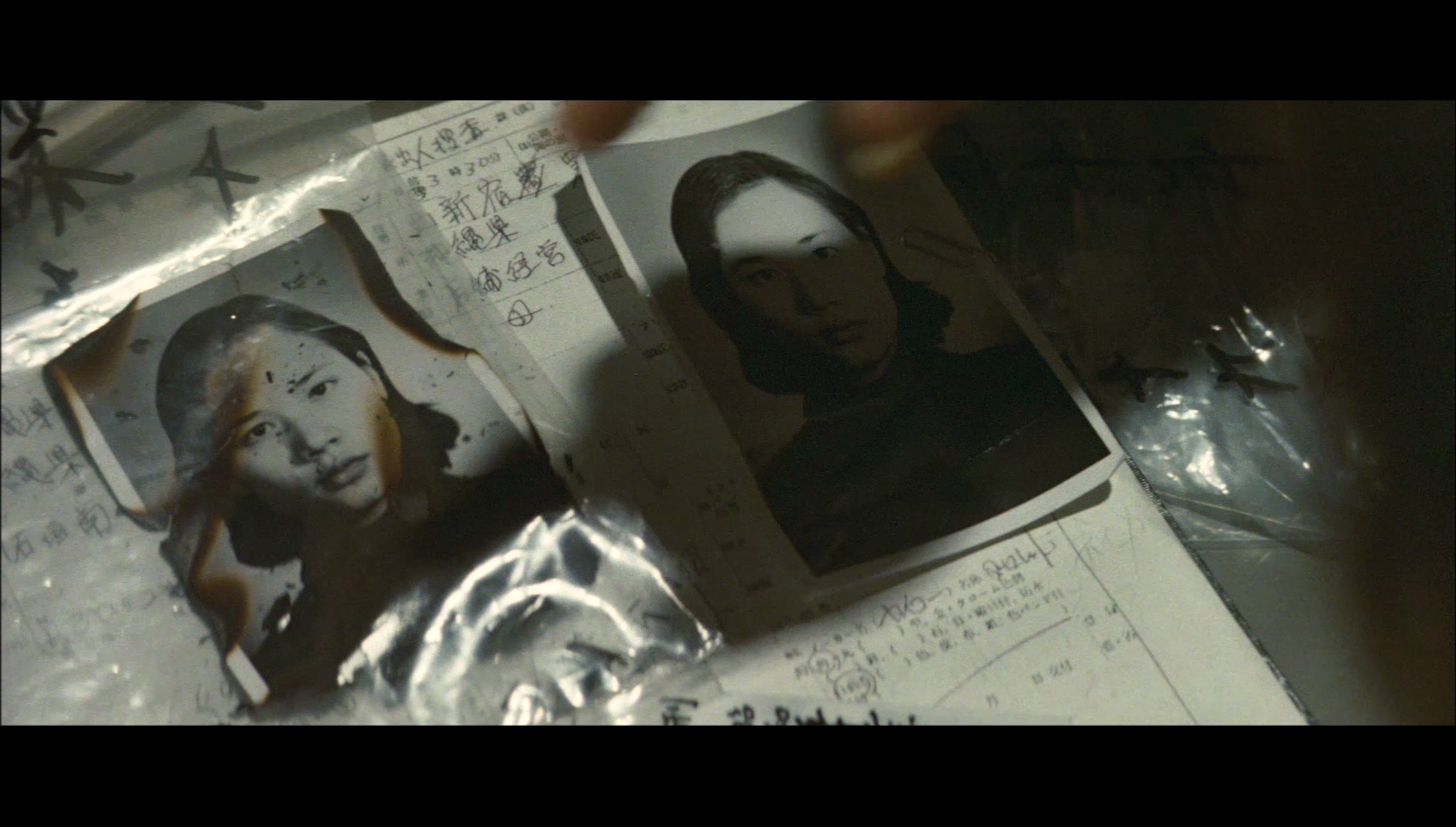

Made after director Fukasaku Kinji’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, which fixed the paradigms of the gritty street-level jitsuroku films of the 1970s, Doberman Cop (1977) marries some of the streetwise ‘grit’ of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku pictures with more outlandish plot elements. The film was based on the manga by Buronson (Okamura Yoshiyuki), the creator of Fist of the North Star. The original manga, Doberman Deka, was published between 1975 and 1979, and formed the basis for two feature films (including this one, and another released in 1996) and a 1980 television series. Buronson’s manga focuses on Kano Joji, a detective in Tokyo’s special crimes unit, who is known for carrying a Ruger Blackhawk handgun chambered to fire .44 Magnum cartridges. Kano is a rogue cop who is frequently under fire for his aggressive handling of suspects. As this description might suggest, Doberman Deka has more than a little in common with Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971). Fukasaku’s film borrows some of the core elements of the manga (the .44 Magnum handgun, for example) whilst deviating from Buronson’s original text in a number of areas.  In Doberman Cop, Chiba Shin’ichi (Sonny Chiba) plays Kano, an Okinawan policeman who arrives in Tokyo to investigate the murder of a prostitute, Tamashiko Mayumi, whose charred body was discovered by police. The police believe that Mayumi is actually a woman named Yuna who came to Tokyo from Ishigaki, the same island as Kano; Yuna’s mother believed that Yuna and Kano were destined to marry one another, but Yuna has been missing for a number of years. Kano is present in Tokyo to investigate whether or not the murdered woman is indeed his beloved. In Doberman Cop, Chiba Shin’ichi (Sonny Chiba) plays Kano, an Okinawan policeman who arrives in Tokyo to investigate the murder of a prostitute, Tamashiko Mayumi, whose charred body was discovered by police. The police believe that Mayumi is actually a woman named Yuna who came to Tokyo from Ishigaki, the same island as Kano; Yuna’s mother believed that Yuna and Kano were destined to marry one another, but Yuna has been missing for a number of years. Kano is present in Tokyo to investigate whether or not the murdered woman is indeed his beloved.

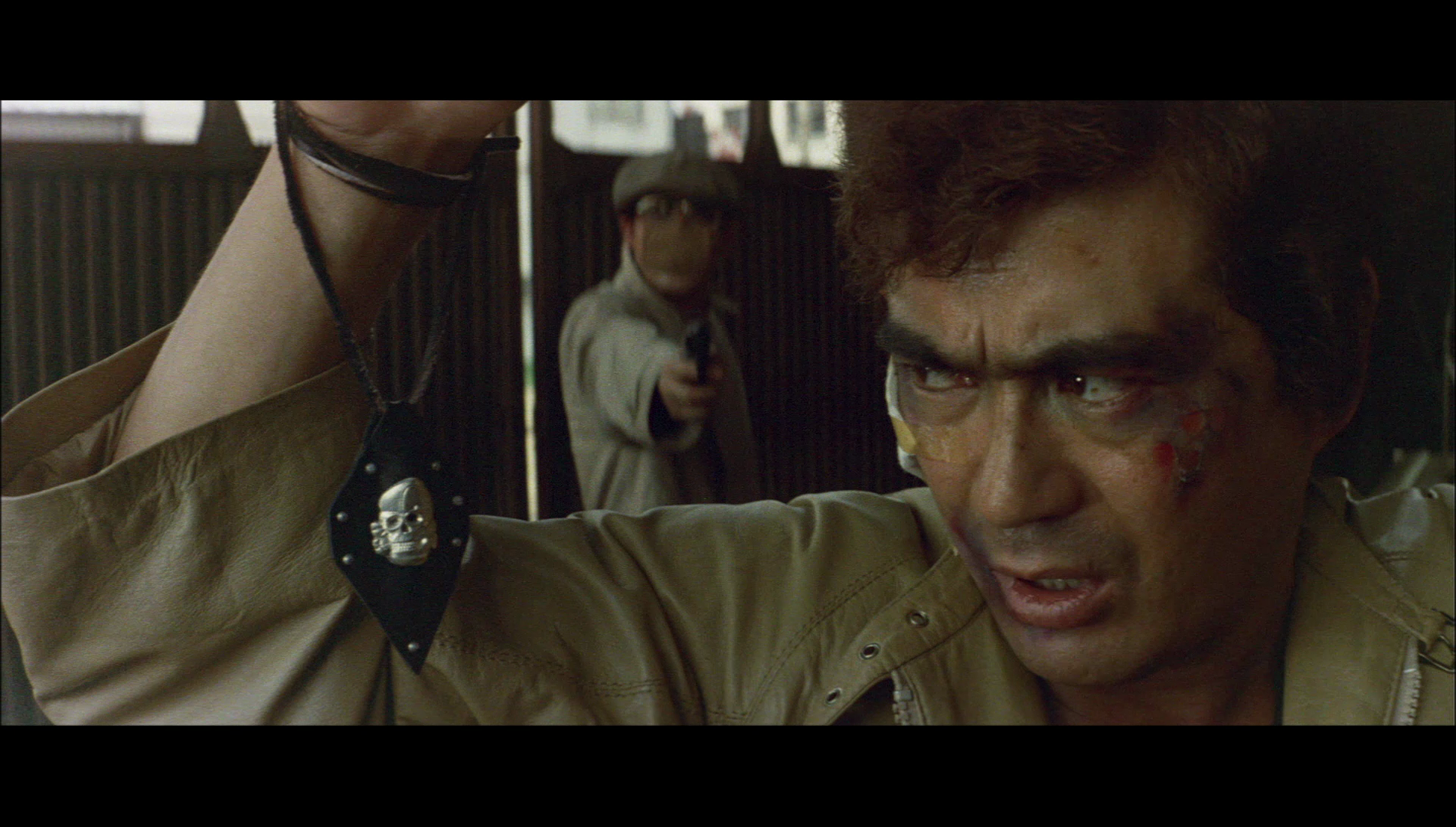

Mayumi’s death is blamed on Hotshot, a young biker who was Mayumi’s lover. Kano isn’t so sure. Wandering through the city streets hoping to find some clues as to the lifestyle of prostitute Mayumi, Kano is directed by a peddler to Kansai Strip Club. There, he is pulled out of the crowd by stripper Kosode (Matsuda Eiko), who engages in coitus with a shocked Kano in front of her audience – much to the chagrin of the club owner/pimp and erstwhile lover. Meanwhile, up and coming singer Haruko Miki (Hatta Janet) is being pushed by her manager, former yakuza Hidemori, to win the television talent show A Star is Born. Miki is competing against the young male singer Mizuki Kenji, who is the favourite of the show’s producer Mr Fujikawa. An addict constantly ‘jonesing’ for her fix, Miki is manoeuvred by Hidemori into winning the competition, whilst backstage Hidemori attempts to curry favour with Mr Fujikawa.  When Miki is taken hostage, apparently by an obsessed fan, Kano rescues her in a bravura act of derring-do, abseiling from a 40-story high rise building to break through the window of Miki’s apartment, arresting the hostage-taker. Captured by television news cameras, this stunt earns Kano the nickname ‘Detective Tarzan’. However, soon after Kano begins to believe that Miki is really Yuna, and that Mayumi was simply a woman who bore a close resemblance to Kano’s former love. Kano teams up with Hotshot and his biker compadres to find out the truth and unmask the serial killer who has been terrorising Tokyo. When Miki is taken hostage, apparently by an obsessed fan, Kano rescues her in a bravura act of derring-do, abseiling from a 40-story high rise building to break through the window of Miki’s apartment, arresting the hostage-taker. Captured by television news cameras, this stunt earns Kano the nickname ‘Detective Tarzan’. However, soon after Kano begins to believe that Miki is really Yuna, and that Mayumi was simply a woman who bore a close resemblance to Kano’s former love. Kano teams up with Hotshot and his biker compadres to find out the truth and unmask the serial killer who has been terrorising Tokyo.

As suggested above, Doberman Cop marries some more bizarre, comic book-style elements (throughout much of the film, Kano carries with him the pig he has brought from Okinawa as a gift for the chief of police) with the gritty, street-level viewpoint of the jitsuroku pictures that Fukasaku was associated with in the early 1970s. Often based on true cases of the yakuza, the jitsuroku films mostly had a semidocumentary aesthetic and in their appropriation of the techniques of documentary filmmaking, their basis in fact, and their cynical worldview, they could be compared with the semidocumentary films noir that appeared in America after the Second World War – beginning with Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street (1945) but also including films such as Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) and Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery (1950). Doberman Cop begins with the graphic image of the charred corpse of the murdered woman, the police surrounding her, the scene illuminated by the flashbulb of a stills camera being used to document the crime. The handheld camerawork conveys intimacy and establishes a verite-style aesthetic. Following this, we are presented with the opening titles, which play out over shots of the neon-drenched city streets of Tokyo whilst, on the soundtrack, a song declares ‘All my memories of you / Are locked deep inside my heart’. The lyrics of the song are associated with Kano as, towards the end of the opening credits, we see Kano walking through the streets: his status as an outsider, a country bumpkin who has come to the city, is signalled immediately via the rustic straw hat that he wears and, of course, the pig that he carries under his arm. Kano presents the pig to the chief of police, asserting that ‘It’s a gift from my mother to thank you for your hospitality’. The Tokyo policemen back away from Kano in shock. Later, Kano takes the pig to the Kansai Strip Club, where he befriends stripper Kosode, who looks after Kano’s pig kindly, doting on it.  Aside from his appearance, Kano differentiates himself from his Tokyo-based colleagues via his belief in superstition: the conflict between the rural and the urban thus becomes subsumed into a conflict between superstition and rationalism. Much of the early sequences of the film involve Kano being mocked by other characters in the film for his rural origins; in his performance as Kano, Chiba seems to channel the stoicism of Clint Eastwood, and in its depiction of Kano as an outsider-policeman whose talents are underestimated by his ‘big city’ colleagues, Doberman Cop has some interesting similarities to Don Siegel’s Coogan’s Bluff (1968). Kano astonishes the detectives in Tokyo by proclaiming that his chief reason for believing Yuna to still be alive is the evidence presented to him on Ishigaki by Yuna’s mother, a priestess who claims that (in the words of Kano) ‘the gods revealed to her that Yuna is still alive’. ‘Yuna was like my wife’, Kano tells the Tokyo detectives, ‘According to her mother, there’s a prophecy that she and I will marry’. In response to this, the other detectives scoff at Kano, the chief of police telling him, ‘You country bumpkin! Do me a favour and go back to the boonies!’ Later in the film, Kano himself practices divination using a handful of beans to ‘prove’ that Yuna is not dead; this leads the other detectives to mock Kano openly. Aside from his appearance, Kano differentiates himself from his Tokyo-based colleagues via his belief in superstition: the conflict between the rural and the urban thus becomes subsumed into a conflict between superstition and rationalism. Much of the early sequences of the film involve Kano being mocked by other characters in the film for his rural origins; in his performance as Kano, Chiba seems to channel the stoicism of Clint Eastwood, and in its depiction of Kano as an outsider-policeman whose talents are underestimated by his ‘big city’ colleagues, Doberman Cop has some interesting similarities to Don Siegel’s Coogan’s Bluff (1968). Kano astonishes the detectives in Tokyo by proclaiming that his chief reason for believing Yuna to still be alive is the evidence presented to him on Ishigaki by Yuna’s mother, a priestess who claims that (in the words of Kano) ‘the gods revealed to her that Yuna is still alive’. ‘Yuna was like my wife’, Kano tells the Tokyo detectives, ‘According to her mother, there’s a prophecy that she and I will marry’. In response to this, the other detectives scoff at Kano, the chief of police telling him, ‘You country bumpkin! Do me a favour and go back to the boonies!’ Later in the film, Kano himself practices divination using a handful of beans to ‘prove’ that Yuna is not dead; this leads the other detectives to mock Kano openly.

Outsider Kano allies himself quickly with those outside mainstream society in Tokyo: principally, Hotshot (the young biker accused by the police of Mayumi’s murder), stripper/prostitute Mosoke and her pimp. These characters are all treated with contempt by the police. ‘People blow into Tokyo all the time, you know’, one of the detectives observes coldly during the investigation into Mayumi’s murder, ‘Unregistered residents, like this Mayumi Tamashiro, there are tens of thousands of them just here in Shinkuku alone’. As Kosode reveals to Kano, suggesting that she was herself someone who ‘blew into’ the city at an earlier stage in her life, ‘Tokyo doesn’t agree with country people. After a month, we all go crazy’. From Hotshot, Kano acquires the Ruger Blackhawk handgun with which his character in the manga on which the film is based is associated. Kano’s makeshift ‘family’ of outsiders, however, is revealed to be far more positive than the world of the police and the yakuza – who, as in Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films, are suggested to be equally corrupt to the point that members of the policeforce and the yakuza are interchangeable and indistinguishable from one another, flipsides of the same coin. When, towards the end of the film, it’s revealed that a policeman is behind the serial murders of prostitutes, including Mayumi, the audience is unlikely to be shocked; the killer is motivated by a desire to ‘cleanse’ Tokyo: ‘With my own hands, I’ll exterminate every single one of them’, he says, referring to ‘young punks’ like Hotshot and his friends ‘who are running Tokyo into the ground’.  In one of the film’s most outrageous scenes, Kano is shown abseiling from the top of a 40-story building to dive into Miki’s apartment and rescue her from the man who has taken her hostage. Of course, later in the film this is revealed to have been a situation engineered by Hidemori in an attempt to elevate Miki’s status as a celebrity prior to the A Star is Born competition. The camera fixes on Chiba’s face, showing that Chiba himself is performing his own stunts, abseiling down the side of the high rise building, in a moment reminiscent of the scenes in Henri Verneuil’s Peur sur la ville (1975) that seek desperately to confirm for the film’s audience that the film’s star (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is indeed performing his own stunts (for example, standing atop a moving train). In one of the film’s most outrageous scenes, Kano is shown abseiling from the top of a 40-story building to dive into Miki’s apartment and rescue her from the man who has taken her hostage. Of course, later in the film this is revealed to have been a situation engineered by Hidemori in an attempt to elevate Miki’s status as a celebrity prior to the A Star is Born competition. The camera fixes on Chiba’s face, showing that Chiba himself is performing his own stunts, abseiling down the side of the high rise building, in a moment reminiscent of the scenes in Henri Verneuil’s Peur sur la ville (1975) that seek desperately to confirm for the film’s audience that the film’s star (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is indeed performing his own stunts (for example, standing atop a moving train).

Miki’s story has something of Jacqueline Susann’s iconic 1960s novel Valley of the Dolls to it, in its depiction of a young Okinawan woman who is swallowed up by the big city, entering into a world of drugs and prostitution via the lure of stardom. The story of Miki depicts the rural space as a place of innocence and naivete, whilst the city is a space of danger, corruption and vice. It seems that Miki is exploited by her manager Hidemori, a former yakuza, though later scenes in the film serve to complicate that simplistic reading of their relationship. Nevertheless, Hidemori is unwilling to let his burgeoning starlet fall back into a life of anonymity: he has staked too much of his own existence on her success. ‘I’ve staked my career on a girl named Miki Haruno’, Hidemori reminds Miki at one point in the film, ‘I’ll make you a star, no matter what’. For Hidemori, being a ‘star’ is of all-consuming importance. ‘What does it mean to be a star?’, Miki asks him, clearly not as invested in her success in the A Star is Born competition as Hidemori is. ‘A star is a star’, Hidemori replies cryptically, ‘It’s not only in showbusiness. There are stars in all fields. To be a star means ultimate victory. In this world, the winners rule’. Later, Hidemori suggests that the world of showbusiness is as corrupt as the world of the yakuza: ‘I’ve staked everything I have on Miki’s talent’, Hidemori tells Mr Fujikawa, ‘But the waters of showbusiness are muddier than a gangster’s’.

Video

The 1080p presentation of the film uses the AVC codec and takes up 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 90:02 mins. The film is presented in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio. The 1080p presentation of the film uses the AVC codec and takes up 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 90:02 mins. The film is presented in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

The anamorphic lenses used in Japanese productions of this vintage are notoriously quirky. Here, vignetting can be seen at the edges of the frame in some shots – a characteristics of the lenses used during production – and at times highlights seem diffused. This is on par with other Japanese films of this era and speaks of the quality of the glass used on the cameras during the film’s production. In keeping with the verite-style aesthetic of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films, the focal lengths used in Doberman Dog seem mostly of the journalistic standard (ie, 35mm), creating a sense of intimacy between the audience and the action that unfolds onscreen. These quirks of the original photography aside, the presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is very good and seems filmic and true to source. Contrast levels are solid throughout, with gradation from light to darkness and defined midtones inbetween. This is evidence from the opening shots of the charred corpse of Mayumi which taper off into darkness, the body picked out via torchlight and the flash bulbs of the stills cameras used by the investigators; light tapers off into strong blacks. Colour is robust: the mostly naturalistic palette is offset by saturated neon reds used, for example, for the film’s opening titles. An excellent level of detail is present throughout the film, and a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented, with Japanese dialogue, via a LPCM 2.0 track. This has good depth and range, showcasing the funky Lalo Schifrin-esque main theme very well. The accompanying optional subtitles are easy to read and make sense throughout, containing no grammatical errors worth mentioning – though they contain plenty of Americanisms (eg, the aforementioned phrase ‘go back to the boonies’). Audio is presented, with Japanese dialogue, via a LPCM 2.0 track. This has good depth and range, showcasing the funky Lalo Schifrin-esque main theme very well. The accompanying optional subtitles are easy to read and make sense throughout, containing no grammatical errors worth mentioning – though they contain plenty of Americanisms (eg, the aforementioned phrase ‘go back to the boonies’).

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Beyond the Film: Doberman Cop’ (8:54). A new interview with Yamane Sadao, the biographer of Fukasaku, sees Yamane reflecting on the position of Doberman Cop within Fukasaku’s body of work. Yamane suggests that the Japanese film industry had changed drastically between the early 1970s and 1977, when this film was made and released; cinema attendance was in decline, and this led to the popularity of manga adaptations – or more specifically, adaptations of gekida, a form of manga with more developed narrative and seen as more ‘serious’ than general manga. (The term gekida is often used in relation to manga in the same way that, amongst English-speaking fans of sequential art, the term ‘graphic novel’ is used in substitution for the more ‘childish’ phrase ‘comic book’.) Doberman Cop was one of a number of films of the era based on a manga source – as the production studios were seen as running out of new ideas, therefore pillaging stories from the world of gekida/manga. Yamane suggests that the film’s relatively poor commercial performance put an end to the potential for a series of films based on the same manga source. The interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Koji Takada: Cops, Pigs, Karate’ (17:55). This new interview with Takada, the writer of the film, begins with Takada reflecting on the arrogance of people involved in film production during the 1970s in terms of their approach to source material. He suggests that Fukasaku was relatively disinterested in the source material for Doberman Cop, resulting in numerous changes to the narrative. Takada reflects on some of the writers who he has the pleasure to meet during his career, and he posits that these writers had ‘confidence in the adaptation process’ because they saw it as an opportunity for their work to be ‘enjoyed twice’. This interview is also in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Sonny Chiba: A Life in Action 2’ (17:53). The second part of Arrow’s new interview with Chiba (the first part can be seen on their release of Yamaguchi Kazuhiko’s 1975 Wolf Guy, reviewed by us here) sees Chiba discussing his working relationship with Fukasaku and reflecting on the qualities of Fukasaku’s pictures: ‘The pace was so swift you didn’t feel time passing’, he says. Chiba talks in some detail about the stuntwork in the film and, in particular, the scene in which he abseils from the 40 story building. Chiba speaks in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - Trailer (3:16).

Overall

If you ever wanted to see Sonny Chiba carrying a pig, wearing a large-brimmed straw hat, being ravaged by a stripper on a stage or abseiling from a 40-story building, this is the film for you. ‘Where’s the kitchen sink?’, I hear you ask. Critical of the quest for fame, and thus having a sense of timeliness for today’s focus on A Star Is Born-style televised singing competitions, Doberman Cop is held together by Chiba’s stoic presence. Kano describes himself as ‘just an Okinawan furimun’ – a ‘crazy person’ – and Kano’s eccentricities and quirks distinguish the film from many of its contemporaries. Doberman Cop is also fairly sexually explicit – almost on a par with Nikkatsu’s ‘Roman Porno’ films of the same era. (Kano’s appearance, wearing a straw hat with a large brim and carrying a pig under one arm, might very well have influenced the appearance of ‘Ryu the Rapist’ in Kurahara Koretsugu’s bizarre Nikkatsu-produced ‘Roman Porno’ picture Erotic Campus: Rape Reception, released the same year as Doberman Cop.) Played by Matsuda Eiko, an actress most closely associated with her explicit role as Abe Sada in Oshima Nagisa’s In the Realm of the Senses (1975), Mosoke is introduced in a strip club act that prominently features a red dildo that is thrust between her breasts and caressed against her cheek. It’s an entertaining picture, an oddball mixture of the semidocumentary style of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films and more outlandish plot elements that betray the film’s basis in a manga, and it makes for an interesting companion piece to the Chiba-starring Wolf Guy, which Arrow have also recently released on Blu-ray. If you ever wanted to see Sonny Chiba carrying a pig, wearing a large-brimmed straw hat, being ravaged by a stripper on a stage or abseiling from a 40-story building, this is the film for you. ‘Where’s the kitchen sink?’, I hear you ask. Critical of the quest for fame, and thus having a sense of timeliness for today’s focus on A Star Is Born-style televised singing competitions, Doberman Cop is held together by Chiba’s stoic presence. Kano describes himself as ‘just an Okinawan furimun’ – a ‘crazy person’ – and Kano’s eccentricities and quirks distinguish the film from many of its contemporaries. Doberman Cop is also fairly sexually explicit – almost on a par with Nikkatsu’s ‘Roman Porno’ films of the same era. (Kano’s appearance, wearing a straw hat with a large brim and carrying a pig under one arm, might very well have influenced the appearance of ‘Ryu the Rapist’ in Kurahara Koretsugu’s bizarre Nikkatsu-produced ‘Roman Porno’ picture Erotic Campus: Rape Reception, released the same year as Doberman Cop.) Played by Matsuda Eiko, an actress most closely associated with her explicit role as Abe Sada in Oshima Nagisa’s In the Realm of the Senses (1975), Mosoke is introduced in a strip club act that prominently features a red dildo that is thrust between her breasts and caressed against her cheek. It’s an entertaining picture, an oddball mixture of the semidocumentary style of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films and more outlandish plot elements that betray the film’s basis in a manga, and it makes for an interesting companion piece to the Chiba-starring Wolf Guy, which Arrow have also recently released on Blu-ray.

This Blu-ray release of Doberman Cop contains a solid presentation of the main feature, taking account of the characteristics of the lenses used during production, and includes some really very interesting contextual material. It’s a welcome addition to Arrow’s lineup and those who enjoyed their recent release of Wolf Guy will find this picture on-par with it. Fans of Fukasaku’s work will do well to note that Doberman Cop is more outrageous than the jitsuroku pictures with which the director is most closely associated, but it certainly shows elements of his style nonetheless.

|

|||||

|