|

|

Future Shock! The Story of 2000 AD (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th July 2017). |

|

The Film

Future Shock! The Story of ‘2000AD’ (2014) Future Shock! The Story of ‘2000AD’ (2014)

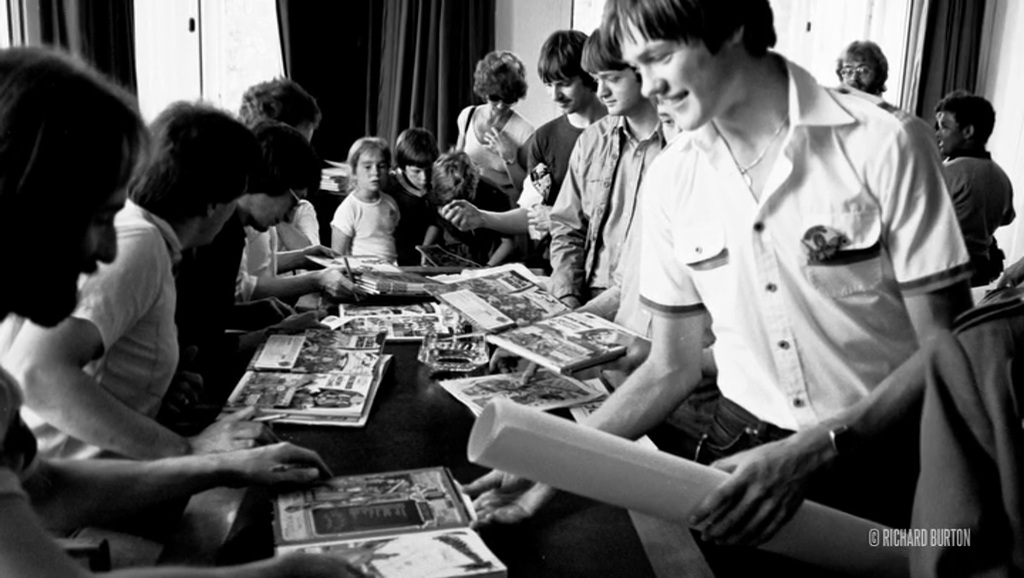

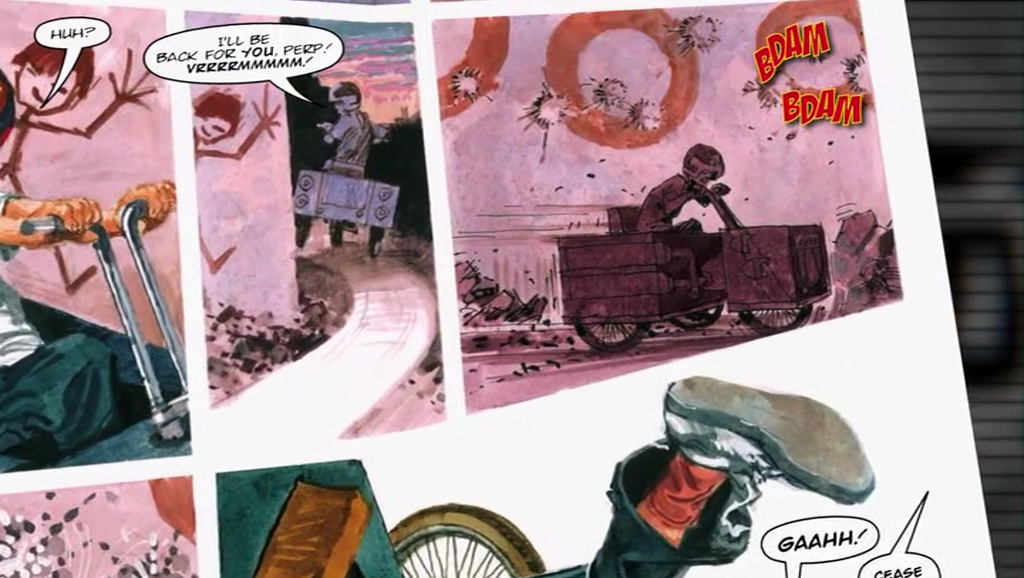

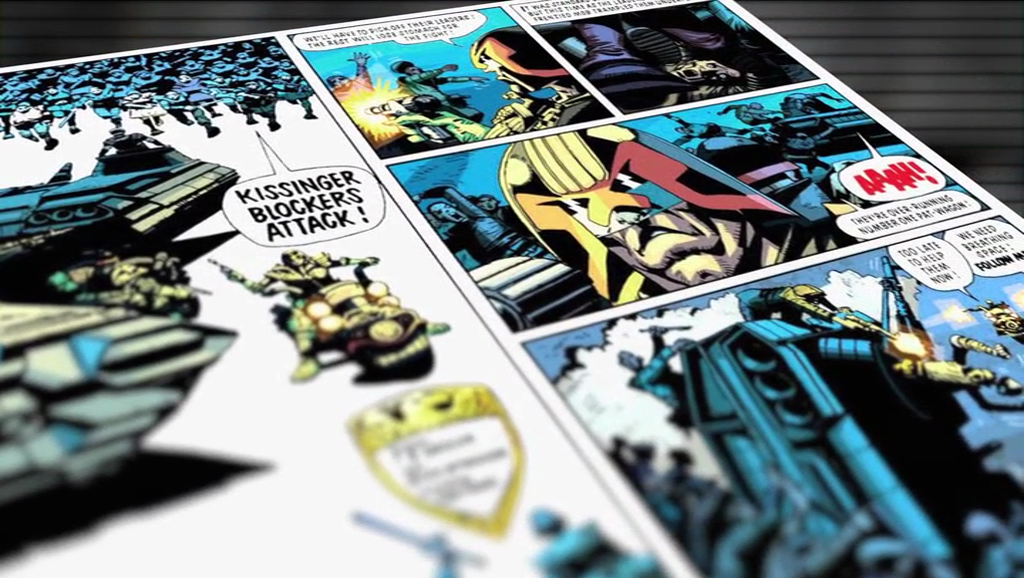

Like many boys growing up in the 1980s, at a certain age I transitioned from the world of The Beano and Dandy to Eagle, Victor and, of course, 2000AD. Moving on to reading 2000AD was the 1980s equivalent of transitioning from shorts to long trousers. (Though Pat Mills makes some disparaging remarks about Eagle in this documentary, in all honesty I remember being equally fond of the 1980s run of that comic as I was of 2000AD.) In fact, one of the highlights of my youth was having a letter published in 2000AD (about, as I recall, the ‘Tharg’s Future Shocks’ column, which I loved). Though this was many years ago, I believe my efforts were rewarded with the ‘letter of the week’ because I received from the publication a toy, a Manta Force vehicle named ‘The Scythe’, and I was so proud of this achievement that this specific toy would be returned to its box each time I finished playing with it, along with the letter I received from the 2000AD offices. The toy has since become a favourite of my own children, so this gift from 2000AD that I received in the late 1980s is one that keeps on giving. At the time, the year 2000 seemed a long way away. (‘Let’s all meet up in the year 2000’, Jarvis Cocker sang in 1995, ‘Won’t it be strange when we’re all fully grown?’). As a number of the interviewees in Future Shock! assert, when the first issue of 2000AD was published, the year 2000 was 23 years into the future and nobody believed that the comic would last into the new millennium. Of course, the year 2000 is now 17 years ago and 2000AD is still going strong, having passed through a number of eras and changes in key personnel – and also offering many of the most important writers associated with modern comics (such as Alan Moore and Grant Morrison) their first significant ‘gig’.  Taking an expository approach but sans a ‘voice of God’ narrator, allowing the interviewees to speak and their comments to sometimes clash, Future Shock! tells the story of 2000AD via interviews with personnel associated with the comic (including creator Pat Mills and writers and artists such as Alan Grant, Dave Gibbons, Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison), academics such as cultural historian Will Brooker and comics historian Paul Gravett, and celebrity fans of the comic including Alex Garland (who wrote the 2012 Dredd film adaptation) and Anthrax’s Scott Ian. These interviews are interspersed with archival news footage, animated sequences depicting pages from the comic appearing on the screen and sometimes coming to ‘life’, and archival photographs. Taking an expository approach but sans a ‘voice of God’ narrator, allowing the interviewees to speak and their comments to sometimes clash, Future Shock! tells the story of 2000AD via interviews with personnel associated with the comic (including creator Pat Mills and writers and artists such as Alan Grant, Dave Gibbons, Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison), academics such as cultural historian Will Brooker and comics historian Paul Gravett, and celebrity fans of the comic including Alex Garland (who wrote the 2012 Dredd film adaptation) and Anthrax’s Scott Ian. These interviews are interspersed with archival news footage, animated sequences depicting pages from the comic appearing on the screen and sometimes coming to ‘life’, and archival photographs.

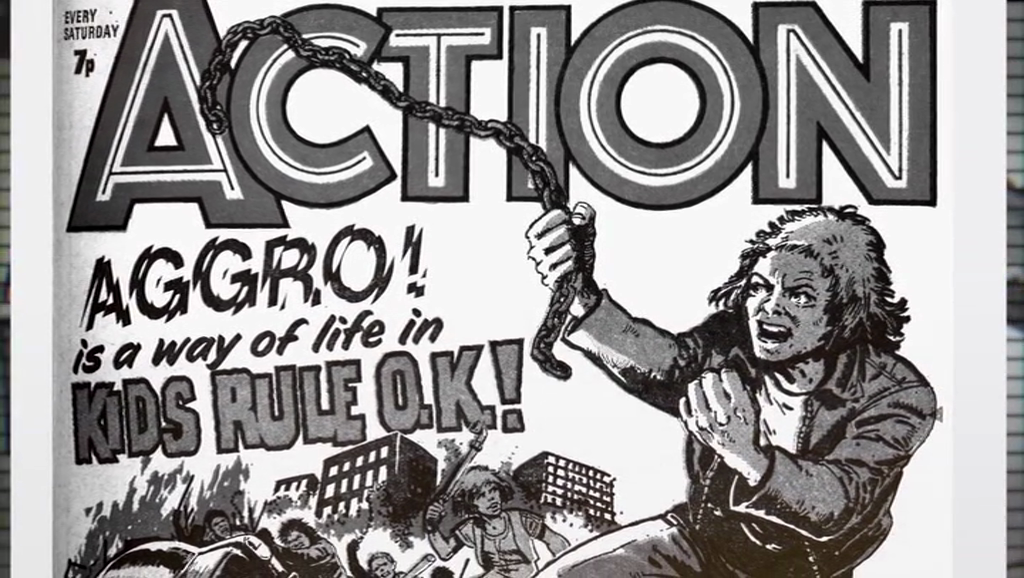

The documentary begins by sketching the social context into which 2000AD was born: Britain of the late 1970s, with its high youth unemployment and blackouts, strikes and the Winter of Discontent. Then the state of boys’ comics in the 1970s is discussed by Pat Mills and Dave Gibbons. Mills suggests that comics in the 1970s were ‘becoming increasingly silly and losing their way’, and this was because the writers of these comics, in Dave Gibbons’ words, ‘didn’t want to be writing comics. They wanted to be writing proper novels or articles for proper magazines’; working in the world of comics was seen as ‘slumming it’ for many of these writers. Mills reflects on his work writing for some of these comics during that period, arguing that ‘It literally was rotting my brain. I’m really convinced it was’. Desiring change, Mills established the short-lived and controversial comic Action, which lasted for only 37 issues. Inspired by 1970s films like Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971) and Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and driven by stories that rooted for the ‘underdog’, Action drew criticism for its violence. ‘I wanted it to be a comic of the streets’, Mills says, ‘and it became this rollercoaster because it was incredibly successful because of its savagery but also because it [held up two fingers] to the establishment’. On Action, Mills collaborated with John Wagner, the writer who would later go on to be instrumental in the creation of Judge Dredd. Wagner admits unashamedly that he likes stories with violence: ‘I particularly like writing violence’, he says, ‘so there’s always a lot of violence in my stories, because it’s fun’. Later in the documentary, in reference to the Judge Dredd strip, Alan Grant quips, ‘We don’t call it violence in comics; we call it “action”’.  Action was eventually cancelled after a series of controversies, but it became what writer Dan Abnett refers to as the slightly misguided prototype’ of 2000AD. Mills regrets the fact that in order to produce the types of action stories that he values, he had to retrench into science fiction, but he admits that the genre gave him and his team much more freedom: ‘For me, personally, there’s a lot of regret we had to retreat into science fiction to be able to say something’, Mills confesses. Mills was influenced more by continental publications like Metal Hurlant than by US science fiction. Action was eventually cancelled after a series of controversies, but it became what writer Dan Abnett refers to as the slightly misguided prototype’ of 2000AD. Mills regrets the fact that in order to produce the types of action stories that he values, he had to retrench into science fiction, but he admits that the genre gave him and his team much more freedom: ‘For me, personally, there’s a lot of regret we had to retreat into science fiction to be able to say something’, Mills confesses. Mills was influenced more by continental publications like Metal Hurlant than by US science fiction.

Mills’ team were treated with distaste by the comics establishment, and Mills suggests that because ‘People thought […] we were a science fiction comic, we were going to be rather nice and middle-class. But boy, were they in for a shock’. However, the controversy that greeted the comic’s initial publication worked in 2000AD’s favour: ‘If you’re launching a new publication’, artist Dave Gibbons says, ‘to get slagged off by the tabloids is a wonderful thing’. Grant Morrison suggests that 2000AD was founded on marrying a sense of social realism with the paradigms of science fiction and injecting into this compound a dose of anarchism: ‘There always was that kind of kitchen sink-Alan Bennett level to British comics’, Morrison says, ‘and there was also the anarchic element coming from The Bash Street Kids [of The Beano….] where it was children against authority [….] What 2000AD did was to take those ideas and put them into adventure scripts’. Brian Bolland argues that the spirit of punk was a ‘motivating factor’, and the publication had an intentional ‘violent, satirical edge’. The development and evolution of Judge Dredd, the character who became 2000AD’s flagship, is reflected on at length. Carlos Ezquerra, the artist responsible for the appearance of Dredd, suggests that the character was based on a melange of symbols: Dredd’s helmet was inspired by the executioner’s hood, and the eagle emblem worn by the judges of Mega City One was influenced by the use of eagles on the Roman eagle standard, by the US, and on the Reichsadler. The commentators reflect on the contradictions involved in the popularity of Dredd amongst the comic’s readership. Writer Alan Grant notes that ‘Dredd is a fascist, and the more fascistic we made him […] the more the readers loved the character’. (As a child reading the comic in the 1980s, Dredd’s similarities with Clint Eastwood’s similarly contradictory Dirty Harry was always evident to me.)  2000AD always had a stratified readership and operated on different levels: the comic appealed to both adults and older children, and its stories of action could be read in a very literal way or taken as metaphor. John Wagner says that ‘We always tried to write stories so that the young could appreciate them and older people could appreciate them’. Paul Gravett, the comics historian, suggests that ‘The multiple levels of reading are what make 2000AD work. I’m quite sure if you were […] say, eight or ten you’d just like things blowing up and guns, etc, and action, and you wouldn’t necessarily pick up on all the other levels of meaning’. For his part, Mills compares the comic to the work of authors such as Charles Dickens, in that both 2000AD and Dickens’ novels confront the ‘social evils’ of their respective eras of production. Artist D’Israeli cites the concept of ‘bread and circuses’ that we get from the Roman poet Juvenal, arguing that the reason why this concept of entertainment as diversion works ‘is that people always prefer to be entertained than engaged. So one way to make sure that they have some sort of understanding is actually encapsulate some of this stuff into the entertainment’. 2000AD always had a stratified readership and operated on different levels: the comic appealed to both adults and older children, and its stories of action could be read in a very literal way or taken as metaphor. John Wagner says that ‘We always tried to write stories so that the young could appreciate them and older people could appreciate them’. Paul Gravett, the comics historian, suggests that ‘The multiple levels of reading are what make 2000AD work. I’m quite sure if you were […] say, eight or ten you’d just like things blowing up and guns, etc, and action, and you wouldn’t necessarily pick up on all the other levels of meaning’. For his part, Mills compares the comic to the work of authors such as Charles Dickens, in that both 2000AD and Dickens’ novels confront the ‘social evils’ of their respective eras of production. Artist D’Israeli cites the concept of ‘bread and circuses’ that we get from the Roman poet Juvenal, arguing that the reason why this concept of entertainment as diversion works ‘is that people always prefer to be entertained than engaged. So one way to make sure that they have some sort of understanding is actually encapsulate some of this stuff into the entertainment’.

Some of the comics’ specific strips and characters are discussed, including Strontium Dog and Nemesis: The Warlock. Some of the ways in which these stories commented on society of the time are discussed in detail, especially the examination of xenophobia in Nemesis: The Warlock. In terms of the comic’s subversive messages, Morrison suggests that ‘Because it [2000AD] was appealing to kids, it was kind of getting through and turning us all into a generation of anarchists’. Mills argues that it’s imperative that ‘You should be giving kids the idea that there are alternative viewpoints’ to those expressed in the mainstream media and by politicians and opinion leaders. The male focus of the comic is discussed through an examination of the highly-regarded Alan Moore strip The Ballad of Halo Jones, which as the commentators here suggest was planned by Moore to be a much larger story but was curtailed by Moore’s departure from 2000AD. Neil Gaiman suggests that ‘Had Alan finished Halo Jones, it would have been one of the first great comics. It would have been up there with Watchmen and with V for Vendetta’.  During the 1990s, the comic underwent what Mills suggests was a ‘dark’ period characterised by ‘too many chiefs and not enough indians’. This led to a period in which some of the artwork kept in the archives of the comic was abused by managers who employed the archival artwork as cutting mats and even doormats. ‘Art bodgers’ were used to erase the signatures of artists in the artwork; reaction to this led to the inclusion of a credit card for the writers, artists and letterers of each story. Naming the creative personnel in this way helped to establish writers of comics as ‘authors’ in their own right. However, a clause in 2000AD’s policy towards writers meant that anyone creating a new character for the comic had to sign over all copyright to the publishers, resulting in writers not being paid when strips were reprinted or sold for development in other media. During the 1990s, the comic underwent what Mills suggests was a ‘dark’ period characterised by ‘too many chiefs and not enough indians’. This led to a period in which some of the artwork kept in the archives of the comic was abused by managers who employed the archival artwork as cutting mats and even doormats. ‘Art bodgers’ were used to erase the signatures of artists in the artwork; reaction to this led to the inclusion of a credit card for the writers, artists and letterers of each story. Naming the creative personnel in this way helped to establish writers of comics as ‘authors’ in their own right. However, a clause in 2000AD’s policy towards writers meant that anyone creating a new character for the comic had to sign over all copyright to the publishers, resulting in writers not being paid when strips were reprinted or sold for development in other media.

In the late 1980s, some of 2000AD’s writers were ‘poached’ by DC, and many of these developed projects for DC’s ‘adult’ imprint Vertigo. Karen Berger, the executive editor of Vertigo between 1993 and 2003, was responsible for hiring many of these writers. Their work, such as Moore’s influential Watchmen, contained a new, darker approach to costumed superheroes of the kind that DC offered (for example, Batman and Superman) and therefore created a paradigmatic shift within the world of American comics. Dave Gibbons suggests that writers like himself and Moore gave ‘an outsider’s view on superheroes and costumed heroes. Much though we loved them, we were a step back; we could question them a bit’. Karen Berger argues that ‘There wouldn’t have been a Vertigo if there wasn’t a 2000AD. The subversiveness, the anarchy, the rebellion against authority all came through Vertigo [from the writers of 2000AD]’. Will Brooker notes that this ‘British invasion’ of the US comics scene brought ‘a sense of authorship […] to American comics’. Gaiman describes the key difference between British and American approaches to superheroes thusly: ‘Americans trust heroes’, Gaiman says, ‘The English would not be able to give Superman that glorious crown the Americans give him […] One of the wonderful messages of 2000AD is “Do not trust your heroes”’.  However, the poaching of 2000AD’s talent by Vertigo was worrying for Mills. Mills argues that to some extent ‘we were nursery slopes for Vertigo. If I found a new artist, I would think, “How long have we got him before he gets pinched by DC?”’ Mills found the idea of writers using 2000AD as a ‘stepping stone’ to American comics quite disrespectful. However, the poaching of 2000AD’s talent by Vertigo was worrying for Mills. Mills argues that to some extent ‘we were nursery slopes for Vertigo. If I found a new artist, I would think, “How long have we got him before he gets pinched by DC?”’ Mills found the idea of writers using 2000AD as a ‘stepping stone’ to American comics quite disrespectful.

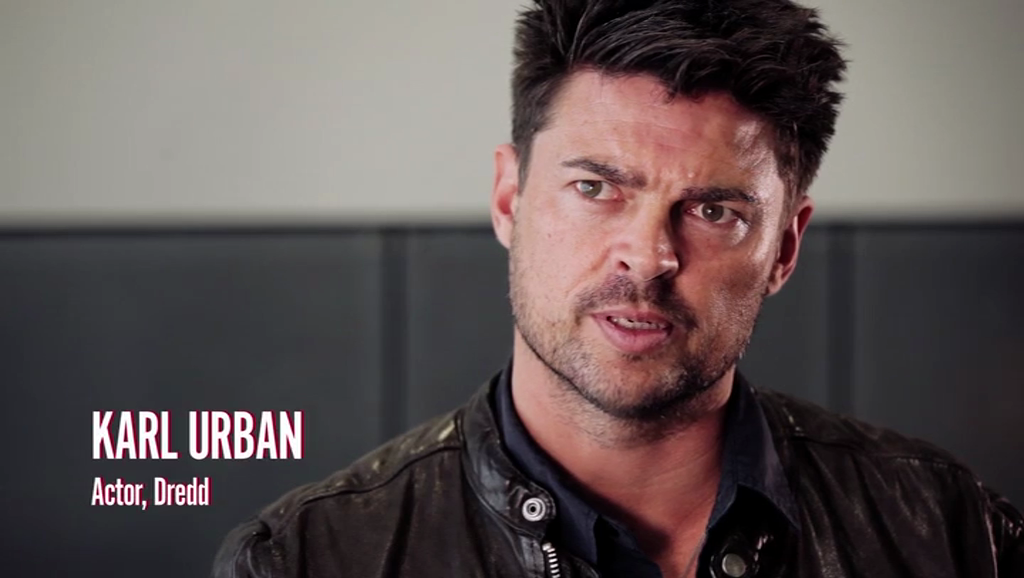

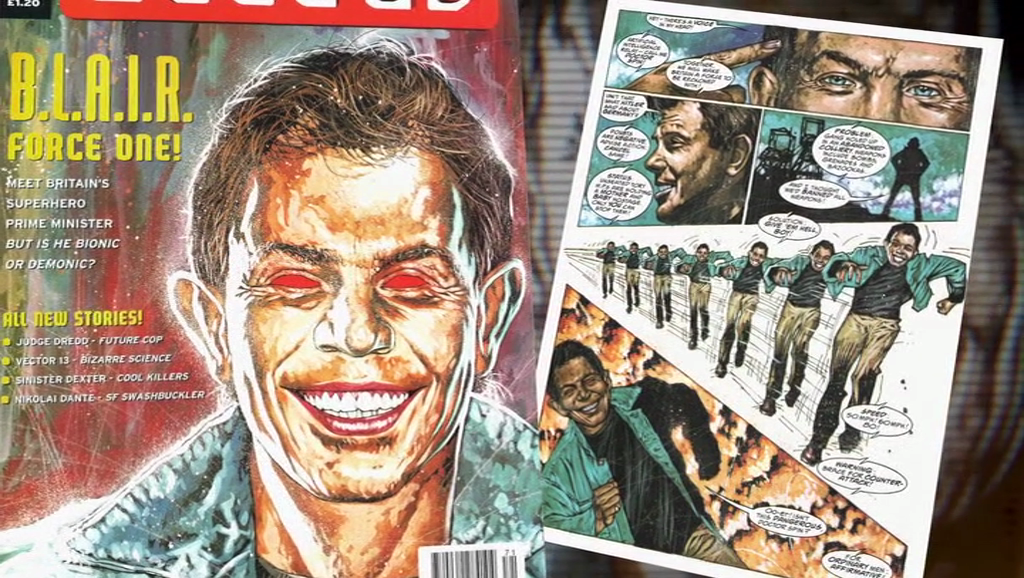

The 1990s era of 2000AD is discussed, with Mills describing Dave Bishop’s tenure as ‘the darl ages of 2000AD’. The comic came close to cancellation during the 1990s, and the publishers attempted to claim a new readership by appealing to the type of audience that read Loaded, producing flyers and front covers that featured buxom, scantily-clad women and so on. The writers suggest that they knew this wouldn’t bring in a new audience and would actually instead alienate some of the comic’s existing audience. (I’ll admit that as a reader of 2000AD, this era pushed me away from the comic.) Wagner suggests that during the Bishop era, ‘It all got a bit too slick and “in” and hip, and it forgot what it was at its core’. The 1996 Danny Cannon-directed Judge Dredd film is discussed in some detail. The film is universally panned by the writers and artists of 2000AD, and for good reason. However, it led the comic’s publisher to establish the subsidiary company Fleetway Film and Television to market 2000AD stories to film and television companies in America. Mills again suggests that this a huge failure, the company failing to understand the material or how to sell it properly. When Andy Diggle took over as 2000AD’s editor in the year 2000, and instantly irritated Mills by sending out a condescending ‘mission statement’ addressed to ‘Mark’ Mills. ‘You suddenly think, “Hey, that’s my child you’re fucking with”’, Mills says, ‘It’s not about bearing a grudge, but I think it was such an awful period [that] it definitely needs recording’. Following this, Rebellion Developments purchased 2000AD, the company seeing their investment in the comic as a ‘rescue mission’. Rebellion’s work with the comic is praised, as is the company’s handling of the comic’s properties – in particular the success of the 2012 film Dredd, directed by Pete Travis and written by Alex Garland. This film is discussed in some detail, with comments from Garland and Karl Urban, who plays Judge Dredd in the picture.  Finally, the influence and lasting legacy of the comic is discussed. There are some notable claims made here: in particularly, the similarities between the Paul Verhoeven-directed, Ed Neumeier-scripted 1987 film RoboCop and the premise (and appearance) of Judge Dredd. Some of the claims arguably stretch the point a little: for example, Morrison’s suggestion that Michael Bay’s Transformers films are influenced more by 2000AD’s strip ABC Warriors than by earlier incarnations of Transformers. Furthermore, some of the elements of 2000AD that are said to have influenced specific films could arguably be interpreted as the key paradigms of dystopic fiction more generally (and could be said to be present in, for example, the work of the SF writers like Arkady and Boris Strugatsky). Nevertheless, some interesting points are made here. Finally, the influence and lasting legacy of the comic is discussed. There are some notable claims made here: in particularly, the similarities between the Paul Verhoeven-directed, Ed Neumeier-scripted 1987 film RoboCop and the premise (and appearance) of Judge Dredd. Some of the claims arguably stretch the point a little: for example, Morrison’s suggestion that Michael Bay’s Transformers films are influenced more by 2000AD’s strip ABC Warriors than by earlier incarnations of Transformers. Furthermore, some of the elements of 2000AD that are said to have influenced specific films could arguably be interpreted as the key paradigms of dystopic fiction more generally (and could be said to be present in, for example, the work of the SF writers like Arkady and Boris Strugatsky). Nevertheless, some interesting points are made here.

Interestingly, one area that isn’t covered in the main feature is the video game adaptations of 2000AD’s strips that appeared in the late 1980s and early 1990s: Dredd, Rogue Trooper, Nemesis: The Warlock, Strontium Dog and Slaine were all adapted for computers such as the Spectrum and the Amstrad CPC during that the 1980s/1990s. It would have been interesting to see some commentary on these as well as the film adaptations.

Video

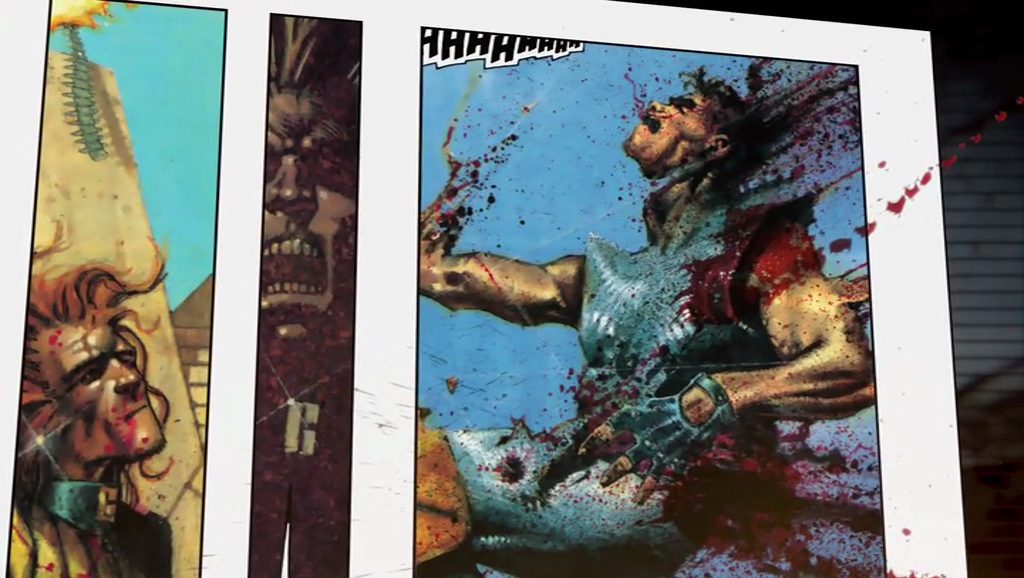

We were provided with a DVD copy of the release (and not the Blu-ray). The DVD presentation runs for 105:14 mins (PAL) and is presented in the 1.78:1 ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. The bulk of the material, the interviews with the participants, is shot on digital video in various interior spaces. This is supplemented by some brief animated segments containing examples of the comic strips and covers, and sometimes bringing strips to life in the form of animated frames. Clips from various films are interspersed throughout the documentary, including Dirty Harry and Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) as well as the two Judge Dredd big screen adaptations. Some newsreel footage is included (the 1970s newsreel footage is shot on 16mm; the newsreel footage included from the 1980s is shot on aged videotape). The archive newsreel footage looks as rough and raw as one might expect, but the bulk of material is presented excellently. We were provided with a DVD copy of the release (and not the Blu-ray). The DVD presentation runs for 105:14 mins (PAL) and is presented in the 1.78:1 ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. The bulk of the material, the interviews with the participants, is shot on digital video in various interior spaces. This is supplemented by some brief animated segments containing examples of the comic strips and covers, and sometimes bringing strips to life in the form of animated frames. Clips from various films are interspersed throughout the documentary, including Dirty Harry and Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) as well as the two Judge Dredd big screen adaptations. Some newsreel footage is included (the 1970s newsreel footage is shot on 16mm; the newsreel footage included from the 1980s is shot on aged videotape). The archive newsreel footage looks as rough and raw as one might expect, but the bulk of material is presented excellently.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 track (on the DVD), which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track isn’t ‘showy’ and has no need to be, but it’s clear throughout and the interviewees comments are always audible. The subtitles are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

Two DVDs are included (all running times are PAL).  DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

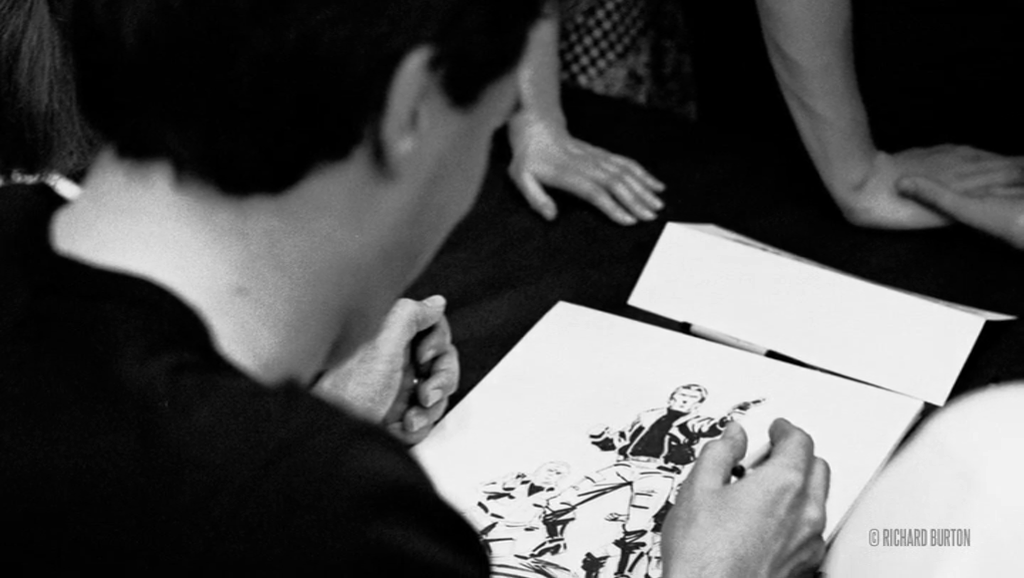

- Steve MacManus Interview (26:20). A new interview, conducted this year for Arrow, sees Steve MacManus, the editor of 2000AD from 1979 to 1986, talking about the defining years of the comic. - Art Jam (3:54). Timelapse footage is used to show Jock and Henry Flint creating artwork for Dredd and Nemesis: The Warlock. - King’s Reach Tower (5:41). Pat Mills revisits King’s Reach Tower, where the comic was created, for the first time since the 1980s - Soundtrack Studio (3:38). This footage offers a ‘behind the scenes’ glimpse of the creation of the music – by Justin Greaves of Crippled Black Phoenix – for the documentary. - Extended Chapter Featurettes. This segment features extensions of some of the topics discussed in the main documentary. o ‘Cheap Entertainment: The Appeal of Comics’ (8:39). Gaiman and others talk about the appeal of comics for them: what makes comics so interesting? o ‘Dredd Extended’ (13:19). Judge Dredd, his appeal and the qualities of the character, are discussed in much more detail by the likes of Mills and Wagner. o ‘Dredd 2012: True in Spirit’ (12:26). The 2012 Dredd film is discussed by Urban, Garland, Jock and Wagner. o ‘2000AD Versus the USA’ (14:34). The interviewees discuss the ‘Britishness’ of the comic and its relationship with American culture. - Blooper Reel (1:59). Here, the interviewees make on-camera boo-boos. - Teaser Trailer (2:01). - UK Launch Trailer (1:59).  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

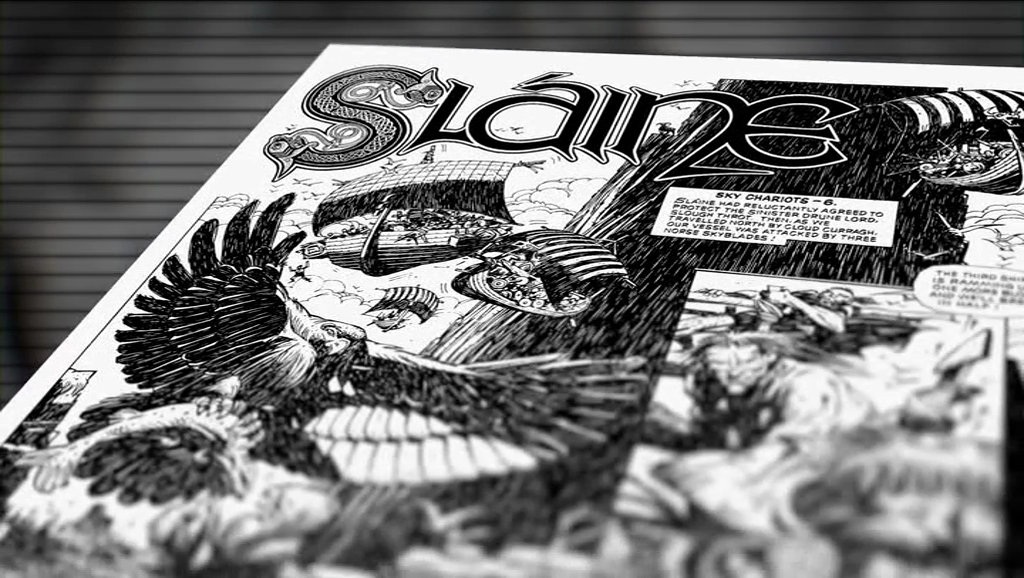

- 2000AD Strip Featurettes (with ‘Play All’ option) o Bad Company / Peter Milligan (4:39). Every reader of 2000AD had their personal favourite strips. My favourite was ‘Bad Company’. I was a little sad to see that ‘Bad Company’ was nary mentioned in the main documentary, but here Peter Milligan (briefly) discusses the origins of ‘Bad Company’ and talks about some of its themes. o Tharg’s FUTURE SHOCKS! / Various (7:50). Here, a number of the interviewees reflect on the one-off short strips ‘Tharg’s FUTURE SHOCKS’. o Rogue Trooper / Dave Gibbons and Cam Kennedy (7:12). Gibbons and Kennedy discuss another of 2000AD’s iconic strips, the superb ‘Rogue Trooper’ – another strip that is surprisingly little-discussed in the main feature. o Slaine / Pat Mills (11:01). Mills discusses his own creation for 2000AD, ‘Slaine’. o Strontium Dog / Carlos Ezquerra (5:10). Ezquerra reflects on ‘Strontium Dog’, another one of 2000AD’s most memorable strips. - Extended Interviews. These are much longer interviews with the following participants, taken from the same sessions from which the interviews in the main feature were culled. An incredible resource! o Pat Mills (83:39) o Grant Morrison (30:56) o Neil Gaiman (14:00) o Dave Gibbons (46:38) o Karen Berger (30:37)

Overall

As an avid reader of 2000AD throughout much of the 1980s and into the early 1990s, I guess I’m part of the core audience for this documentary; and for those of us who grew up reading the comic, Future Shock is a great blast of nostalgia and a remembrance as to why this specific comic was so important and what it did to further both the culture and significance of comic books and their relationship with the concept of authorship. Mills is a little sniffy about some of 2000AD’s contemporaries (as noted above, I was quite fond of the 1980s run of Eagle at that time and also enjoyed Victor and, less frequently, Battle), and too much time at the end of the documentary is spent picking apart the influence 2000AD has had on popular culture: the comic has been undeniably influential, but some of the claims made here about the comic’s supposed direct influence on certain specific films and genres are a little bold, and I would have preferred for this section of the documentary to be trimmed and replaced with discussion of some of the strips neglected within the documentary (eg, ‘Bad Company’ or ‘Rogue Trooper’). It’s also surprising, given the quite astonishing proliferation of video game adaptations of 2000AD stories during the 1980s (almost all of the publications’ main strips were translated into computer games during the decade), that little is made of the relationship between the comic and a computer-literate, video games-playing audience. As an avid reader of 2000AD throughout much of the 1980s and into the early 1990s, I guess I’m part of the core audience for this documentary; and for those of us who grew up reading the comic, Future Shock is a great blast of nostalgia and a remembrance as to why this specific comic was so important and what it did to further both the culture and significance of comic books and their relationship with the concept of authorship. Mills is a little sniffy about some of 2000AD’s contemporaries (as noted above, I was quite fond of the 1980s run of Eagle at that time and also enjoyed Victor and, less frequently, Battle), and too much time at the end of the documentary is spent picking apart the influence 2000AD has had on popular culture: the comic has been undeniably influential, but some of the claims made here about the comic’s supposed direct influence on certain specific films and genres are a little bold, and I would have preferred for this section of the documentary to be trimmed and replaced with discussion of some of the strips neglected within the documentary (eg, ‘Bad Company’ or ‘Rogue Trooper’). It’s also surprising, given the quite astonishing proliferation of video game adaptations of 2000AD stories during the 1980s (almost all of the publications’ main strips were translated into computer games during the decade), that little is made of the relationship between the comic and a computer-literate, video games-playing audience.

Nevertheless, this is a documentary that explores 2000AD respectfully, giving it the attention it deserves whilst also reminding the viewer just how much of an assault upon the sensibilities of the establishment the comic was. This release contains an amazing array of contextual material, including a handful of more recent interviews and much more footage from the main batch of interviews used to assemble the documentary. Anyone interested in comic books, and especially fans of 2000AD, will find this to be an absolutely essential purchase.

|

|||||

|