|

|

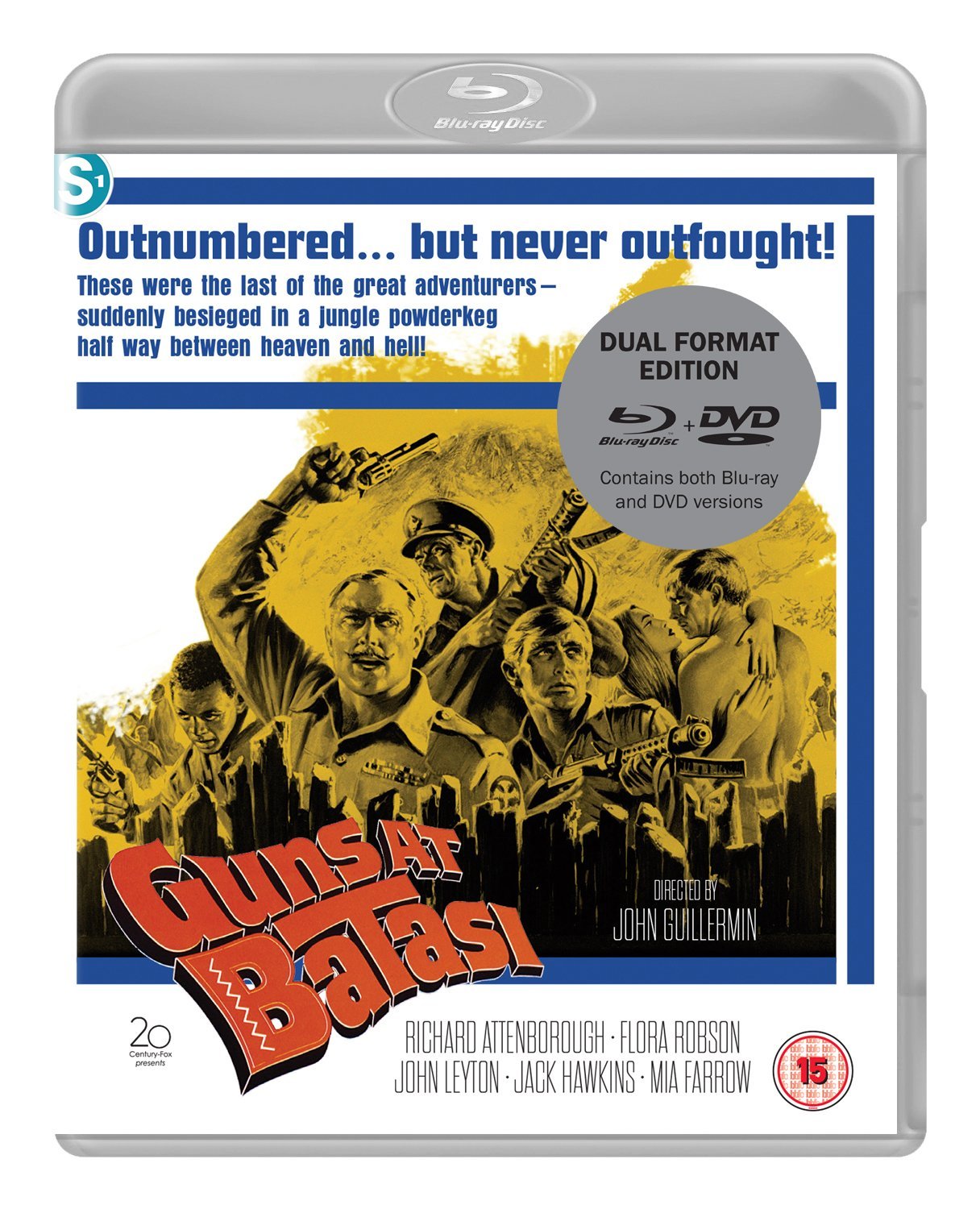

Guns at Batasi (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th August 2017). |

|

The Film

Guns at Batasi (John Guillermin, 1964) Guns at Batasi (John Guillermin, 1964)

In the African district of Batasi, demonstrations are organised in support of the rebel leader Jobila. The area has recently been freed from British colonial rule, though remnants of the British army remain at the headquarters of the 2nd Battalion of African Rifles in an advisory role, training and assisting the local troops. The British troops are under the control of Colonel Deal (Jack Hawkins) and are anticipating the arrival of British Member of Parliament Miss Barker-Wise (Flora Robson), who is sympathetic towards the pro-Jobila rebels. The troops are kept in line by Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) Lauderdale (Richard Attenborough). Lauderdale is fixated on protocol and tradition, reflecting on the glory days of the empire. In the sergeants’ mess, the other sergeants remove the Queen’s portrait from the rear wall for a joke and place bets on how long it will take Lauderdale to notice its absence; of course, Lauderdale spots it immediately. ‘You may think you know me, gentlemen; you may think you can see me coming’, Lauderdale says, ‘But consider this: there’s no alteration, celebration, no argumentation and no qualification in this mess that escapes my little eye’. Colonel Deal receives news that Deal is to hand over the running of the camp to Captain Abraham (Earl Cameron). Following Deal’s departure from the camp, however, Abraham is betrayed by one of his own men, Lieutenant Boniface (Errol John). Organising a group of pro-Jobila rebels within the ranks of the African military, Boniface has Abraham and a group of other pro-government soldiers captured and driven out of the camp, where they are shot with submachine guns when they try to escape.  The sergeants’ mess sees the arrival of Private Wilkes (John Leyton) and pretty United Nations employee Karen Eriksson (Mia Farrow), both of whom were due to return to England via aeroplane but, upon discovering their flight was cancelled, instead headed to the camp until safe passage back home could be rearranged. Barker-Wise also makes an appearance, much to the chagrin of Lauderdale, who immediately takes a dislike to the woman. The sergeants’ mess sees the arrival of Private Wilkes (John Leyton) and pretty United Nations employee Karen Eriksson (Mia Farrow), both of whom were due to return to England via aeroplane but, upon discovering their flight was cancelled, instead headed to the camp until safe passage back home could be rearranged. Barker-Wise also makes an appearance, much to the chagrin of Lauderdale, who immediately takes a dislike to the woman.

Badly wounded, Abraham manages to make his way back to camp and into the sergeants’ mess, where unaware of the rebellion by Boniface, Lauderdale and the other sergeants – Ben (Percy Herbert), ‘Dodger’ (Graham Stark), ‘Schoolie’ (Bernard Horsfall), ‘Muscles’ (David Lodge) and ‘Aussie’ (John Meillon) – await their orders from Colonel Deal, and just as they make a toast to the Queen in honour of her birthday. Realising that they are in the midst of a mutiny, Lauderdale and the other sergeants hatch a plan to acquire weapons and ammo from the stores. They bluff their way into the stores and acquire a host of rifles, submachine guns and machine guns. Boniface soon approaches the sergeants’ mess and tells the group assembled there to co-operate with him, but Lauderdale reminds Boniface that Colonel Deal is the sergeants’ commanding officer and they will not recognise Boniface’s assertion of authority over the camp. Boniface demands that Lauderdale hand over Abraham, or else Boniface will order his rebel troops to fire a pair of ack-ack guns at the sergeants’ mess, killing everyone within it. Lauderdale refuses to obey, however, and plots a daring mission to disable the ack-ack guns with a pair of grenades, for which he requires the assistance of the inexperienced Private Wilkes.  The character played by Mia Farrow, Karen Eriksson, was originally to have been played by Britt Ekland. Ekland had recently married Peter Sellers, and Sellers was notoriously possessive of his bride, believing her to be involved in a relationship with costar John Leyton. Sellers reputedly commissioned ‘spies’ on the set of Guns at Batasi, who were tasked with reporting back to Sellers the activities of his wife. In a matter of days, Ekland left the production to return to her husband and was replaced by Farrow; Ekland’s scenes were reshot, and the picture became Farrow’s big screen debut. In response to Ekland’s departure, Fox filed a lawsuit against the actress, also naming Sellers, for breach of contract and to the tune of $4.5 million. Sellers attempted to counter-sue but was eventually forced to pay Fox a little over $60,000 (see Sikov, 2011). (Ironically, in 1965 Sellers was nominated for Best Actor at the BAFTAs for his role in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove but lost out to Richard Attenborough, who was nominated in the same category for his performance as RSM Lauderdale in Guns at Batasi.) The character played by Mia Farrow, Karen Eriksson, was originally to have been played by Britt Ekland. Ekland had recently married Peter Sellers, and Sellers was notoriously possessive of his bride, believing her to be involved in a relationship with costar John Leyton. Sellers reputedly commissioned ‘spies’ on the set of Guns at Batasi, who were tasked with reporting back to Sellers the activities of his wife. In a matter of days, Ekland left the production to return to her husband and was replaced by Farrow; Ekland’s scenes were reshot, and the picture became Farrow’s big screen debut. In response to Ekland’s departure, Fox filed a lawsuit against the actress, also naming Sellers, for breach of contract and to the tune of $4.5 million. Sellers attempted to counter-sue but was eventually forced to pay Fox a little over $60,000 (see Sikov, 2011). (Ironically, in 1965 Sellers was nominated for Best Actor at the BAFTAs for his role in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove but lost out to Richard Attenborough, who was nominated in the same category for his performance as RSM Lauderdale in Guns at Batasi.)

Guns at Batasi was made in the middle of a turbulent decade in the history of South Africa, with a number of territories freeing themselves from British colonial rule during the early 1960s. The film narrativises this period of post-colonialism, exploring the tensions between the traditional colonial mindset – represented by RSM Lauderdale – and the more ‘modern’ sensibilities of politicians such as Miss Barker-Wise. During the decade, a number of films were made that represented and interrogated the concept of colonialism and the myths associated with the age of empire (in particular, the opposition between ‘order’ imposed by the coloniser and the ‘disorder’ represented in the rebellions directed against colonising agents): many of these films, such as Cy Endfield’s Zulu (1964), Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) and Gerald Thomas’ Carry On… Up the Khyber (1968), featured historical settings. Others, such as Guns at Batasi, were more ‘daring’ in setting their narratives at a time of ‘handover’ during the then-present day, often featuring soldiers – like RSM Lauderdale – who reflect on past glories of the days of empire. Guns at Batasi is particularly cynical about the process of regime change: at the start of the film, Dodger and Ben are driving through Batasi and see the pro-Jobila demonstrators waving placards and blocking the streets. ‘What do you reckon they’re up to?’, Dodger asks Ben. ‘I don’t know’, Ben replies, ‘They got rid of our government. Perhaps they want to get rid of their own’. For their part, the African soldiers regard British culture with humour: when they are told that a female Member of Parliament will be visiting the camp, they laugh. ‘Oh, women in Parliament have their uses, you know’, Schoolie says in response to this. ‘What uses, sir?’, one of the African soldiers asks him, ‘To carry water?’  Perhaps unusually for a war picture made during the 1960s, especially one about the British Empire, Guns at Batasi was shot on monochrome 35mm stock. (Compare this with, for example, the lush colours of Cy Endfield’s Zulu, released the same year, or David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, released in 1962.) Less than a year later, Sidney Lumet’s remarkable The Hill (1965) was similarly shot in monochrome, and as with The Hill, Guns at Batasi’s black-and-white photography throws emphasis on character rather than action and spectacle; the film is as much about Richard Attenborough’s RSM Lauderdale and his worldview – and how this dictates his reactions to this situation of stress – as it is about the coup. As the narrative progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that Lauderdale is the focus of the storym and Guns at Batasi is at its essence a psychological study of this officer. Perhaps unusually for a war picture made during the 1960s, especially one about the British Empire, Guns at Batasi was shot on monochrome 35mm stock. (Compare this with, for example, the lush colours of Cy Endfield’s Zulu, released the same year, or David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, released in 1962.) Less than a year later, Sidney Lumet’s remarkable The Hill (1965) was similarly shot in monochrome, and as with The Hill, Guns at Batasi’s black-and-white photography throws emphasis on character rather than action and spectacle; the film is as much about Richard Attenborough’s RSM Lauderdale and his worldview – and how this dictates his reactions to this situation of stress – as it is about the coup. As the narrative progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that Lauderdale is the focus of the storym and Guns at Batasi is at its essence a psychological study of this officer.

Though superficially separated from the British ‘New Wave’ via its exotic setting, in its exploration of alienated masculinity – Lauderdale’s education in the romantic myths and legends surrounding British troops in the age of the empire meeting a cold end in the era of post-colonialism – Guns at Batasi might invite comparison with the era of British social realism and the focus on masculine alienation in films such as Look Back in Anger (Tony Richardson, 1959), This Sporting Life (Lindsay Anderson, 1963), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Karel Reisz, 1960) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (Tony Richardson, 1960). Tony Richardson’s later The Charge of the Light Brigade covers some similar territory, Richardson’s ‘training’ in British social realism colliding with the historical setting of the Battle of Balaclava, deconstructing the myths surrounding Britishness, masculinity and the age of empire. Wendy Webster notes that though superficially, Lauderdale ‘is very far removed from the Angry Young Men’ by virtue of his position in society and his regimented mindset (as compared with the rebelliousness of many of the Angry Young Men in the aforementioned examples of the British ‘New Wave’), both Guns at Batasi and Look Back in Anger ‘register the loss of a romance of manliness, of fering [sic] similar analyses of national malaise. Why are there “no good, brave causes left”?—Jimmy Porter’s lament. Why are British soldiers reduced to impotence?—the lament of Guns at Batasi’ (Webster, 2007: np). Webster concludes that both texts lay the blame on politicians and women (ibid.).  Where many of the aforementioned films about the empire, such as Lawrence of Arabia and Zulu, emphasised wide open spaces and spectacle, the majority of the narrative of Guns at Batasi takes place in the sergeants’ mess. The final moments of action involve Lauderdale and Wilkes assaulting the ack-ack guns that Boniface has commanded to be pointed at the sergeants’ mess: they devise a plan of action that will allow them to cross the distance between the guns and the mess hall – which is a matter of a few hundred yards – without being seen by Boniface and his men. This involves the other sergeants distracting Boniface’s men by singing a number of songs, including the perennial British army favourite ‘John Brown’s Body’, at the top of their voices whilst Lauderdale and Wilkes quietly sneak around the prefab buildings that make up the camp. Wendy Webster has argued that in the condensed, unromantic spaces in which the story takes place, Guns at Batasi offers a lament for the loss of the British Empire ‘as a possible location where adventure romance could continue to be imagined’, ultimately ‘demonstrat[ing] just how far it has become impossible to imagine romance in a postcolonial context’ (Webster, op cit.). Where many of the aforementioned films about the empire, such as Lawrence of Arabia and Zulu, emphasised wide open spaces and spectacle, the majority of the narrative of Guns at Batasi takes place in the sergeants’ mess. The final moments of action involve Lauderdale and Wilkes assaulting the ack-ack guns that Boniface has commanded to be pointed at the sergeants’ mess: they devise a plan of action that will allow them to cross the distance between the guns and the mess hall – which is a matter of a few hundred yards – without being seen by Boniface and his men. This involves the other sergeants distracting Boniface’s men by singing a number of songs, including the perennial British army favourite ‘John Brown’s Body’, at the top of their voices whilst Lauderdale and Wilkes quietly sneak around the prefab buildings that make up the camp. Wendy Webster has argued that in the condensed, unromantic spaces in which the story takes place, Guns at Batasi offers a lament for the loss of the British Empire ‘as a possible location where adventure romance could continue to be imagined’, ultimately ‘demonstrat[ing] just how far it has become impossible to imagine romance in a postcolonial context’ (Webster, op cit.).

The ‘villain’ of the piece is arguably Flora Robson’s politician Miss Barker-Wise, who the narrative suggests has inspired Boniface to take part in the coup – and who protests against Lauderdale’s strict following of protocol, arguing that Lauderdale should simply concede to Boniface’s demands – but who by the film’s resolution admits that though she does not agree with Lauderdale, she finds herself in similar disagreement with the methods of Boniface and his associates. (‘I disapprove of his [Boniface’s] methods as much as I do yours’, she admits to Lauderdale in the film’s final sequence.) Barker-Wise initially praises Boniface as a ‘humane’ and ‘cultured’ man, but the film proves him to be anything but: Boniface is shown ordering the deaths of prisoners, and displaying a profound misunderstanding of etiquette when he refuses to remove his hat upon entering the sergeants’ mess. (For Lauderdale, the latter seems as much an offence as the former.) However, Barker-Wise is forced to realise her error in judgement vis-à-vis Boniface when she leaves the mess and asks Boniface for medical aid for the wounded Captain Abraham – only to discover that Boniface instead orders his men to kill Abraham. ‘I don’t understand’, Barker-Wise tells Boniface, ‘When you were in England, you were so different’. ‘Yes, I was one of your African mascots then, wasn’t I?’, Boniface reminds her, ‘Sitting at your feet, listening to you talk [….] No-one talks better than the British. They drug you with talk; when you wake up, they still have their heel on your neck’. Barker-Wise is depicted as naïve, (mis)reading the political situation of the region from a distance. ‘Now listen to me, ma’am’, Lauderdale tells her at one point, ‘You’re not in Parliament now. This isn’t England. And I know more about these people than you do. And don’t run away with the idea that I’ve got a down on them because their skin isn’t the same colour as mine. Their best is as good as our best; but they’re bad’s as rough as ours, and that’s pretty rough’. When Barker-Wise protests that Lauderdale’s attitude is ‘intolerable’, he tells her to ‘blame your harmless little Africans’. ‘Blame them?’, Barker-Wise queries, ‘Who taught them to shoot? You!’ ‘And if it wasn’t for people like us, you wouldn’t be able to walk around spouting your smarmy, silly, bloody half-baked ideas’, Lauderdale responds. For much of the film’s running time, Barker-Wise offers a shadowy echo of much of Lauderdale’s behaviour: like him, Barker-Wise is unmarried, drinking whisky and smoking with abandon. Wendy Webster suggests that she is a castrating figure, ‘reducing men to impotence’ (Webster, op cit.) In the film, thanks to politicians such as Barker-Wise the British army is ‘immobilized by the process of decolonization, pinned down in barracks. When they do take action it is to move only a few yards, still within sight of the mess’ (ibid.).  Perhaps more problematically, Webster asserts that Guns at Batasi ‘continuously asserts the racial superiority of the British and at the same time shows that such superiority no longer provides any guarantee of authority or power’ (Webster, op cit.). The film does this, according to Webster, by ‘contrast[ing] African mayhem and British order’ (ibid.). Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that Lauderdale makes this suggestion – and though he’s a deeply sympathetic character, Lauderdale isn’t depicted as an unproblematic ‘hero’, his values in near-constant dialogue with those of Miss Barker-Wise. At one point, Barker-Wise challenges Lauderdale’s ideas about the African troops directly: ‘I take it, sergeant-major, that you do not believe all men are equal’, she asserts. ‘Equal, ma’am, but different’, Lauderdale responds, ‘Now, you take the horse and the zebra. They’re equal in a manner of speaking, but if you was to plunk them down side by side, feed them on the same grub, in the same climate, one of ‘em would turn his toes up, wouldn’t he, ma’am?’ Though Barker-Wise is depicted as a shrewish influence, her meddling in the affairs of men like Boniface at least partly responsible for the situation in which the characters find themselves, her criticisms of Lauderdale’s behaviour occasionally ring true – and the film’s denouement doesn’t wholly validate Lauderdale’s methods. Perhaps more problematically, Webster asserts that Guns at Batasi ‘continuously asserts the racial superiority of the British and at the same time shows that such superiority no longer provides any guarantee of authority or power’ (Webster, op cit.). The film does this, according to Webster, by ‘contrast[ing] African mayhem and British order’ (ibid.). Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that Lauderdale makes this suggestion – and though he’s a deeply sympathetic character, Lauderdale isn’t depicted as an unproblematic ‘hero’, his values in near-constant dialogue with those of Miss Barker-Wise. At one point, Barker-Wise challenges Lauderdale’s ideas about the African troops directly: ‘I take it, sergeant-major, that you do not believe all men are equal’, she asserts. ‘Equal, ma’am, but different’, Lauderdale responds, ‘Now, you take the horse and the zebra. They’re equal in a manner of speaking, but if you was to plunk them down side by side, feed them on the same grub, in the same climate, one of ‘em would turn his toes up, wouldn’t he, ma’am?’ Though Barker-Wise is depicted as a shrewish influence, her meddling in the affairs of men like Boniface at least partly responsible for the situation in which the characters find themselves, her criticisms of Lauderdale’s behaviour occasionally ring true – and the film’s denouement doesn’t wholly validate Lauderdale’s methods.

Lauderdale’s final assault on the ack-ack guns seems almost like a deliberately self-destructive act: seemingly doomed to failure, Lauderdale is intent on enacting the imperial heroism of the stories on which he was raised. (‘You couldn’t beat India though’, he says in a discussion with the other sergeants about the empire, ‘“Jewel of the East”, they used to call it. What a pity they had to go and give it away!’) When in an earlier sequence, the men in the mess swap stories about the glory days of the empire, it is signalled for the audience that Lauderdale will seek to retreat into that era, and his action against the ack-ack guns represents this. That Lauderdale and Wilkes succeed in disabling the guns is miraculous. However, when Colonel Deal arrives at the sergeants’ mess and advises Lauderdale of the change in government – suggesting that the British army will continue in their capacity as friendly advisors to the new ruling authority, before sending Lauderdale back home to England – the viewer is left wondering whether Barker-Wise may in part have been correct: by doing as Boniface demanded, surrendering their arms and sitting the night out without taking action, Lauderdale and the others would have saved themselves a lot of strife – and, more significantly, would have had just as much impact on the rebellion. We might reflect on Barker-Wise’s assertion that Lauderdale is ‘a living gun. They’ve turned you into a human rifle’. Though effective in achieving their goals, Lauderdale’s efforts were ultimately for nought. Before leaving the camp for good, Lauderdale returns to the mess and dismisses the others in the room. Left alone with his drink, Lauderdale throws the glass in a temper at the portrait of the Queen that hangs behind the bar; earlier Lauderdale was seen fussily tidying this portrait, noticing immediately when Ben and the others removed it from the wall and hid it as a prank, but as the film reaches its conclusion the portrait becomes the target of Lauderdale’s impotent rage. Lauderdale leaves the camp; though his stiff march suggests that his adherence to protocol will remain unbroken by his experiences, it is clear that he – and the type he represents – no longer has a place in post-colonial Africa.

Video

The film takes up just over 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 103:03 mins. Guns at Batasi is also presented in its original widescreen ratio of 2.35:1. The film takes up just over 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 103:03 mins. Guns at Batasi is also presented in its original widescreen ratio of 2.35:1.

The 35mm monochrome photography is crisp and filled with detail in this presentation. A superb level of fine detail is present throughout the film, especially in close-ups of the actors’ faces. Douglas Slocombe, who photographed the picture, seems to have favoured shorter focal lengths for the majority of the production (the barrel distortion is noticeable when the camera pans), with the concomitant increase in depth of field creating a sense of depth to the interiors (most of the film is set in the sergeants’ mess). This sense of depth is communicated very well within this presentation. Some travelogue-style stock footage is introduced here and there, and this is of noticeably lower quality; there is also some rear projection work which looks a little ropey – but these qualities are all commensurate with the original photography. The monochrome image benefits from excellent contrast levels. The sense of harsh outdoor light is communicated effectively by carefully balanced exposures resulting in deep shadows cast by the sun. Midtones have excellent definition, and highlights are even and baalcned throughout. There is little to no damage, other than a slight flickering in a few scenes which seems to be the result of density fluctuations in the emulsions on the source used for this presentation. Finally, a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, grain seeming natural and without the disruptive interference of digital smoothing or sharpening algorithms.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track (in English, naturally), which is crisp and clear throughout, demonstrating good range and ensuring dialogue is always audible. The audio track is accompanied by English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and accurate, though some archaic spellings occur in a handful of instances (eg, the word ‘seized’ is spelt as ‘seised’ – not an error, of course, but unusual all the same; then again, it’s no more unusual than Attenborough’s pronunciation of ‘zebra’ as ‘zee-brah’ in one particular scene).

Extras

The disc includes: - An audio commentary by actor John Leyton. This is the same commentary track that appeared on the R1 Fox DVD release from about a decade ago. Leyton offers some fascinating first-hand anecdotes from the production in a commentary track that has some significant periods of silence but is nevertheless rich in information. - A stills gallery. - The film’s original trailer (2:51).

Overall

Guns at Batasi has some wonderful sequences – notably, the sequence in which Lauderdale bluffs his way past Boniface’s guards and into the armoury. Attenborough’s performance is the highlight, though Douglas Slocombe’s photography is as excellent as most of Slocombe’s work. Less a war film than a character study of Lauderdale and the type that he represents, in its examination of masculinity and alienation Guns at Batasi has more in common with the contemporaneous British ‘New Wave’ films of the era than its ‘exotic’ setting might suggest; the best point of comparison may very well be Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (a film that would make for an interesting double-bill with Guns at Batasi). Guillermin’s picture belongs to a significant line of films about the end of the age of empire and the myths associated with colonialism – from ‘prestige’ pictures such as David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia to comedies like Carry on… Up the Khyber and The Virgin Soldiers (John Dexter, 1969). Guns at Batasi has some wonderful sequences – notably, the sequence in which Lauderdale bluffs his way past Boniface’s guards and into the armoury. Attenborough’s performance is the highlight, though Douglas Slocombe’s photography is as excellent as most of Slocombe’s work. Less a war film than a character study of Lauderdale and the type that he represents, in its examination of masculinity and alienation Guns at Batasi has more in common with the contemporaneous British ‘New Wave’ films of the era than its ‘exotic’ setting might suggest; the best point of comparison may very well be Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (a film that would make for an interesting double-bill with Guns at Batasi). Guillermin’s picture belongs to a significant line of films about the end of the age of empire and the myths associated with colonialism – from ‘prestige’ pictures such as David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia to comedies like Carry on… Up the Khyber and The Virgin Soldiers (John Dexter, 1969).

Signal One Entertainment’s new Blu-ray release of Guns at Batasi contains an excellent presentation of the main feature that showcases Slocombe’s crisp widescreen monochrome photography very well. The release also ports over the commentary track by John Leyton that previously appeared on the R1 DVD release of the picture (from Fox) but was absent on the previously-available UK DVD releases of the film. The release continues Signal One’s run of highly commendable releases of classic films. References: Sikov, Ed, 2011: Mr Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers. London: Macmillan Webster, Wendy, 2007: Englishness and Empire, 1939-1965. Oxford University Press Please click on the following images for full-size screengrabs:

|

|||||

|