|

|

Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st August 2017). |

|

The Film

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Tobe Hooper, 1986) The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Tobe Hooper, 1986)

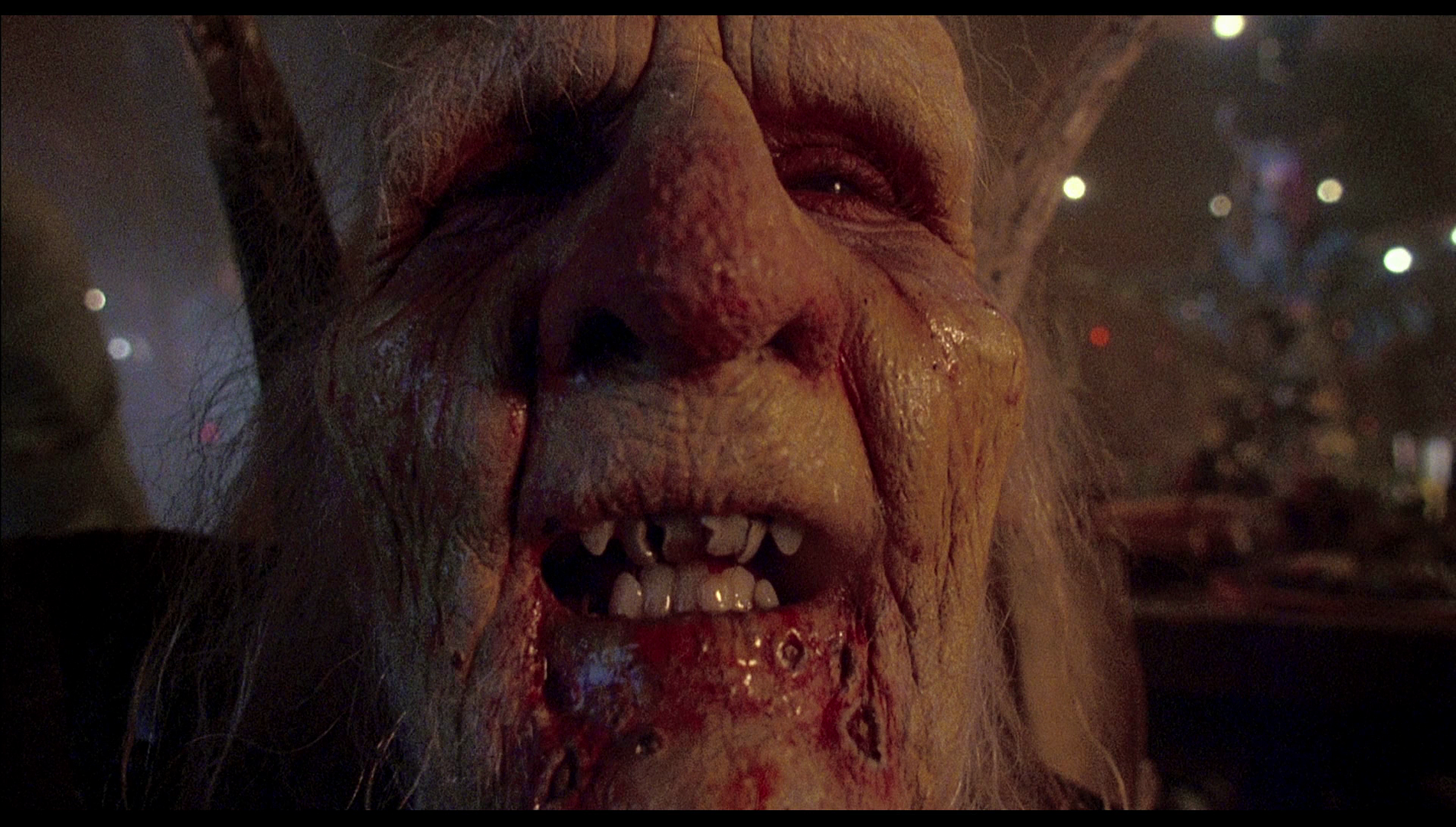

Following the grisly murder by chainsaw of two yuppies who were driving through Texas, former Texas Ranger Lefty Enright (Dennis Hopper), the uncle of Sally Enright (the sole survivor of the events depicted in Tobe Hooper’s original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, 1974), contacts spunky radio DJ ‘Stretch’ (Caroline Williams). Immediately prior to their murder, the dead yuppies had placed a call to Stretch’s radio station, K-OKLA in Burkburnett, Texas, and consequently Stretch’s friend and studio technician LG (Lou Perryman) is in possession of an audio recording of the young men’s final moments. Desperately seeking retribution for the unsolved murders of Sally’s friends and invalid brother Franklin twelve years prior (a crime which the police seem unwilling to investigate further) and believing the yuppies to have been killed by the same people, Lefty asks Stretch to play the audio recording on the airwaves – hoping to smoke the killers out of the proverbial woodwork. Unbeknownst to Lefty, the family of killers he is after are the Sawyers, headed by older brother Drayton Sawyer (Jim Siedow), a local celebrity known for his beloved chilli. Sawyer is introduced whilst being declared the winner of the Texas-Oklahoma Chilli Cookoff competition, and in his speech he declares that the secret of his success is ‘the meat. Don’t skimp on the meat’. Of course, he neglects to mention that the meat in question is the human flesh of the Sawyer family’s victims.  Stretch’s decision to take Lefty’s request and play the recording of the yuppies’ murder on the airwaves results in a visit from the Sawyer family – Chop Top (Bill Mosley), a Vietnam veteran who after suffering an injury in combat was fitted with a metal plate in his skull, and who uses a wire coathanger to scrape the loose flesh from around this metal plate so that he may eat it; and his brother ‘Bubba’, the chainsaw-wielding and childlike Leatherface (Bill Johnson). Chop Top dispatches LG with a hammer, whilst Leatherface pursues Stretch into the studio. Stretch exploits Leatherface’s clear sense of lust for her, and against Chop Top’s orders Leatherface allows her to live. Stretch’s decision to take Lefty’s request and play the recording of the yuppies’ murder on the airwaves results in a visit from the Sawyer family – Chop Top (Bill Mosley), a Vietnam veteran who after suffering an injury in combat was fitted with a metal plate in his skull, and who uses a wire coathanger to scrape the loose flesh from around this metal plate so that he may eat it; and his brother ‘Bubba’, the chainsaw-wielding and childlike Leatherface (Bill Johnson). Chop Top dispatches LG with a hammer, whilst Leatherface pursues Stretch into the studio. Stretch exploits Leatherface’s clear sense of lust for her, and against Chop Top’s orders Leatherface allows her to live.

Chop Top and Leatherface take LG’s body to their vehicle. They drive away from the radio station. Stretch follows them to an abandoned theme park, Texas Battle Land, where the Sawyers live in underground caves decked out with mummified corpses and fairy lights. Stretch is surprised to see Lefty there too, and when Stretch falls through a shaft into the lair of the Sawyers, Lefty enters the caves after her, intent on wreaking vengeance upon the cannibalistic family for their murders of his nephew Franklin and many others. During the 1980s, Tobe Hooper agreed to a three-picture deal with Cannon Pictures which resulted in Lifeforce (1985), Hooper’s remake of Invaders from Mars (1986) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. All three films were received negatively, with Invaders from Mars earning back less than half its budget, and perhaps accordingly with each successive film Hooper’s budgets shrank: Lifeforce was given a budget of $25 million, and Invaders from Mars was made for $12 million. The third and final film in this collaboration between Hooper and Cannon, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 was budgeted at $2.5 million but went massively over-budget, reputedly owing to the involvement of Dennis Hopper and Tom Savini. (The film was ultimately made for around $6 million.)  Owing to bitterness over the manner in which the considerable financial success of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had not filtered its way back to the film’s cast and crew, the cast of the original film – including Gunnar Hansen, Marilyn Burns, John Dugan and Edwin Neal - only agreed to return for their roles if they were paid well (see Muir, 2002: 37). Cannon refused to offer these actors the fees that they believed they were worth. Jim Siedow was the only member of the original cast to return for the sequel, playing as the eldest brother of the Sawyer family – known simply as ‘Cook’ in the original film but here given the name Drayton Sawyer. Owing to bitterness over the manner in which the considerable financial success of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had not filtered its way back to the film’s cast and crew, the cast of the original film – including Gunnar Hansen, Marilyn Burns, John Dugan and Edwin Neal - only agreed to return for their roles if they were paid well (see Muir, 2002: 37). Cannon refused to offer these actors the fees that they believed they were worth. Jim Siedow was the only member of the original cast to return for the sequel, playing as the eldest brother of the Sawyer family – known simply as ‘Cook’ in the original film but here given the name Drayton Sawyer.

In the years since the release of the first picture, Hooper had previously written a number of drafts for a sequel to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre with Kim Henkel, the co-writer of the first picture, but eventually collaborated on the screenplay with L M ‘Kit’ Carson. Hooper initially intended only to produce the film but owing to the haste with which the film was rushed into production, he agreed to direct it too (see Muir, op cit.: 37). During production, Carson was forced to rewrite scenes on the set, and the shoot was also hampered by a second unit crew that bodged one of the film’s major setpieces (see ibid.). When The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 was completed, the MPAA refused to give it an ‘R’ rating, and Cannon decided to release the picture without an MPAA classification; the resultant lack of advertising hampered the film’s ability to reach its audience, and many fans of the original film were also alienated by the sequel’s ironic, playful tone (see Muir, op cit.: 38). In the UK, the film was withheld until 2001: though never officially submitted to the BBFC, the BBFC made it clear that the film would need to be cut severely before it could be awarded an ‘18’ certificate. Consequently, no distributor submitted the film to the BBFC for UK classification until 2001, when it was passed uncut.  Like Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead 2: Dead by Dawn (1987), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is an out-and-out self-parody, re-enacting scenes from the original film and retreading a familiar narrative structure whilst introducing a heavier dose of black comedy. Hooper later suggested that the film’s attempts to mesh overt humour with Tom Savini’s grisly realistic makeup effects was a recipe for disaster: ‘I feel that the film came out of my frustration at the comedy in the first film not being appreciated or understood’, he said, ‘And so I amplified the comedic aspects, but at the same time Tom Savini made everything so anatomically correct and cost so much, that […] the film ended up not even getting a rating. I like the film as wacky, crazy, bizarre over-the-top comedy, but it missed its mark’ (Hooper, quoted in ibid.). Like Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead 2: Dead by Dawn (1987), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is an out-and-out self-parody, re-enacting scenes from the original film and retreading a familiar narrative structure whilst introducing a heavier dose of black comedy. Hooper later suggested that the film’s attempts to mesh overt humour with Tom Savini’s grisly realistic makeup effects was a recipe for disaster: ‘I feel that the film came out of my frustration at the comedy in the first film not being appreciated or understood’, he said, ‘And so I amplified the comedic aspects, but at the same time Tom Savini made everything so anatomically correct and cost so much, that […] the film ended up not even getting a rating. I like the film as wacky, crazy, bizarre over-the-top comedy, but it missed its mark’ (Hooper, quoted in ibid.).

The film features recognisable members of the cannibalistic family from the first picture but here humanises them, and makes them more comical, by giving them names, so the ‘Cook’ of the original film becomes Drayton Sawyer, a local celebrity known for his award-winning chilli; Hooper originally intended for the ‘Hitchhiker’ to become Paul Sawyer, aka ‘Chop Top’, though when the film went into production Chop Top became the Hitchhiker’s twin brother, the Hitchhiker – killed towards the end of the first picture – being present in the completed Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 as a partially mummified corpse that Chop Top animates like a puppet and speaks to as if his brother were still alive. Even Leatherface becomes more humanised, both through performance (for example, his repeated dance of frustration, in which he holds the chainsaw over his head and wiggles his hips, and his desire for Stretch) and in name (Drayton and Chop Top repeatedly refer to Leatherface as ‘Bubba’). It’s clear that the childlike Leatherface becomes sexually fascinated by Stretch… well, more accurately, Hooper hammers that point home in the sequence in which Chop Top and Leatherface terrorise LG and Stretch in the radio studio, Leatherface pursuing Stretch into the recording booth where he places his chainsaw between Stretch’s parted legs, running the blade of the saw up her thigh and pushing it against her groin as he appears to orgasm. The scene seems deliberately to court controversy by representing Leatherface’s weapon of choice, the saw, as a symbolic phallus. Towards the end of the film, after the family has taken Stretch captive, Drayton tells Leatherface he must choose between his desire for Stretch and his family: ‘You got one choice’, Drayton says, ‘Sex or the saw. Sex is… well, nobody knows. But the saw… The saw is family!’  Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 foregrounds the relationship between the family’s cannibalistic practices and Grandpa’s work in the slaughterhouse, Drayton Sawyer telling the captive Stretch that Grandpa was one of the most efficient slaughterhouse workers, schooled in the use of the hammer to dispatch the animals, until increased mechanisation of the process via the use of pneumatic captive bolt devices, etc, made him redundant. Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 foregrounds the relationship between the family’s cannibalistic practices and Grandpa’s work in the slaughterhouse, Drayton Sawyer telling the captive Stretch that Grandpa was one of the most efficient slaughterhouse workers, schooled in the use of the hammer to dispatch the animals, until increased mechanisation of the process via the use of pneumatic captive bolt devices, etc, made him redundant.

The opening sequence supplants the countercultural youths of the first film, with their hippie-style dress, for a pair of yuppies. Two young men with neat hairdos and preppy clothes, one of them wearing novelty sunglasses, drive through Texas; the young man with the sunglasses fires a revolver out of the window at a number of targets, including a series of mailboxes and two signs by the roadside (one declaring ‘Refight Battle of San Jacinto’, the other asserting ‘Remember Battle of the Alamo’). These young men are immediately pegged as products of the 1980s, disrespectful towards history or culture and only interested in self-gratification. They use a car phone (another signifier of yuppie excess) to call Stretch’s radio studio, humiliating the DJ. Later in the evening, they call the radio station again but are confronted on the road by the Sawyer’s vehicle, Leatherface standing atop the truck with the Hitchhiker’s corpse in front of him dancing like a puppet. Leatherface fires up his chainsaw and attacks the yuppies’ vehicle with it, killing the two young men; their deaths are recorded by LG owing to the radio station’s policy of recording all external telephone calls. Robin Wood noted that what made the cannibalistic family in the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre somewhat sympathetic was the sense that they were victims too – ‘of the slaughter-house environment, of capitalism’ (Wood, 2003: 83). Certainly, in the sequel the audience is likely to cheer on Leatherface in his annihilation of the yobbish yuppies, encouraging the audience to identify with Leatherface – if not his brothers – before we have been introduced to the film’s protagonists, Stretch and Lefty.  As Lefty Enright, uncle to Sally (and, in the original script for Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, long-lost father to Stretch), Dennis Hopper steals the show. The film was one of a number of pictures released in the 1980s in which Hopper played a ‘dangerous’ father figure, joining his performances in pictures such as Out of the Blue (directed by Hopper himself in 1980) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish (1983). In 1986, Hopper featured in a number of films that featured incendiary performances by the actor: his work in this film is arguably the equal of his roles in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Tim Hunter’s River’s Edge (both also released in 1986). As Lefty Enright, uncle to Sally (and, in the original script for Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, long-lost father to Stretch), Dennis Hopper steals the show. The film was one of a number of pictures released in the 1980s in which Hopper played a ‘dangerous’ father figure, joining his performances in pictures such as Out of the Blue (directed by Hopper himself in 1980) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish (1983). In 1986, Hopper featured in a number of films that featured incendiary performances by the actor: his work in this film is arguably the equal of his roles in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Tim Hunter’s River’s Edge (both also released in 1986).

In Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, Hopper’s Lefty Enright is a former Texas Ranger who is treated with subtle derision by his former colleagues in law enforcement for his dogged pursuit of those who attacked Sally and killed her brother Franklin; Lefty correctly believes a group of chainsaw-wielding killers were responsible for this crime, and has traced similar activity across Texas in the fourteen years since the events depicted in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Lefty believes his faith makes him immune to the influence of the Sawyers. ‘I got a perfect willingness to die’, he tells Stretch upon their first meeting at the radio station, ‘That gives me a moral on this bunch of mad dogs. They live on fear. They thrive on it. I ain’t got no fear left’. However, law enforcement officials believe him to be nothing more than a crank. Turning up at the wreck of the yuppies’ convertible, Lefty tells a detective that the chainsaw killers were responsible for this incident too, but a local detective responds by asserting that the crash was just an accident. Lefty notices the marks in the car’s body where the chainsaw bit into it and comments dryly, ‘Yep, one of those boys so wild [he] sawed his own head off goin’ ninety miles per hour’. In response to the detective’s assertion that the two yuppies were hellraisers, Lefty notes that ‘Hell’s exactly what they raised’. Lefty sits himself in his car and places a cigarette between his lips, tightening his jaw so that the cigarette points directly into the air comically (and in obvious resemblance of an erect penis – this visual joke is far less funny when it’s explained verbally) before driving away.  One of Hopper’s most memorable scenes takes place when Lefty decides to fight fire with fire and visits ‘Cut-Rite Chain Saws’, a rural shop. Lefty parks his car (and, inexplicably, whilst he’s exiting a marching band passes him in the background – it’s a subtly strange moment that’s presented without explanation in the narrative); upon entering the shop, he is presented with a dazzling array of chainsaws of all shapes and sizes. He selects three: two single handed saws and a longer one. Lefty holds the two shorter saws, one in each hand, like a gunslinger might hold a pair of pistols. The shop’s elderly owner asks Lefty if he would like to try the saws out, escorting his customer to a large log placed outside the building which seems to be present solely for the purpose of allowing the shop’s customers to test their new purchases. Lefty carries the three saws out of the building with him, before turning them on and chopping at the log with them as if they were swords. The elderly owner watches on with shock that quickly turns to glee. ‘Oh, my achin’ banana!’, he declares, giggling incessantly as Lefty hacks at the log with the saws, sawdust flying up into Lefty’s face. One of Hopper’s most memorable scenes takes place when Lefty decides to fight fire with fire and visits ‘Cut-Rite Chain Saws’, a rural shop. Lefty parks his car (and, inexplicably, whilst he’s exiting a marching band passes him in the background – it’s a subtly strange moment that’s presented without explanation in the narrative); upon entering the shop, he is presented with a dazzling array of chainsaws of all shapes and sizes. He selects three: two single handed saws and a longer one. Lefty holds the two shorter saws, one in each hand, like a gunslinger might hold a pair of pistols. The shop’s elderly owner asks Lefty if he would like to try the saws out, escorting his customer to a large log placed outside the building which seems to be present solely for the purpose of allowing the shop’s customers to test their new purchases. Lefty carries the three saws out of the building with him, before turning them on and chopping at the log with them as if they were swords. The elderly owner watches on with shock that quickly turns to glee. ‘Oh, my achin’ banana!’, he declares, giggling incessantly as Lefty hacks at the log with the saws, sawdust flying up into Lefty’s face.

At the film’s climax, Lefty enters Texas Battle Land with the intention of rescuing Stretch and bringing an end to the Sawyers’ reign of terror. Lefty carries with him the three saws, using them to chop down the struts supporting the caves in which the cannibalistic family live. As he does so, Lefty cries ‘Take it all down! Bring it all down! Bury the devil’, making pleas to God (‘Lord, show me what I fear, so I don’t fear it no more’). As he approaches the central part of the complex (‘It’s the devil’s playground!’, he observes), where Stretch is being tortured by Leatherface, Chop Top and Drayton, Lefty sings the gospel song ‘Bringing in the sheaves’. Chop Top seems animated by this and begins singing the song too. Lefty leaps from a large pipe in the ceiling, chastising the family (‘Boys, boys, boys. Never should have been doin’ this’). In this moment, the film’s two figures of male authority – Lefty and Drayton – face one another, their respective rhetoric clashing and highlighting the tensions within Reagan’s America between the evangelical (represented by Lefty) and the Drayton’s rhetoric which focuses on business and money, and which regurgitates the macho aphorisms so frequently parodied in 1980s films like this, Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) and the corporate boardroom scenes in Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987). Drayton demands to know who Lefty is, believing him to be one of his business competitors (‘Why sent ya? Those sissies over at Delmar Catering? That chickenshit burrito man?’). Drayton continues by spitting out some of the aforementioned aphorisms associated with the world of high pressure finance and business: ‘Well, I don’t care. It’s a dog eat dog world, and from where I sit there just ain’t enough damn dogs. You can’t stand the heat, get outta the goddamn kitchen!’ Finally, Drayton offers Lefty money: ‘Let’s make a deal right here… Real cash money’, he says whilst unfolding a wad of bank notes. To this, Lefty asserts simply that ‘I’m the Lord of the Harvest’. ‘Who’s that?’, Drayton asks, ‘Some little health food bunch?’  Sawyer, on the other hand, represents that most ideal of citizens in Reagan’s America, the small businessman (‘a big businessman is what a small businessman would be if only the government would get out of the way and leave him alone’, Reagan famously asserted in 1984). In another echo of Reagan’s rhetoric and policies, Sawyer rants against taxation: ‘It’s the little guy that can’t make a dime!’, he complains, ‘He pays the taxes. Small businessman gets it in the ass every time’. However, Sawyer has commercialised the trade in human meat, using the flesh from the bodies of his victims as the basis for his beloved chilli. In the caves underneath Battle Land, Stretch witnesses Leatherface preparing LG’s corpse, swapping his chainsaw for an electric carving knife which he wields in just the same way as he peels LG’s skin from his thighs, waist and face. Kevin Connor’s 1980 picture Motel Hell offered a similar parody of the meat ‘business’ (and also climaxed with a similar chainsaw duel to Hooper’s film), as did Rick Roessler’s Slaughterhouse (1987), though the Sawyer’s ‘business model’ seems arguably to be based on the relationship between ‘demon barber’ Sweeney Todd and his neighbour, piemaker Mrs Lovatt, in the Tod Slaughter Sweeney Todd: Demon Barber of Fleet Street (George King, 1936). There’s a touch of the superb Prime Cut (Michael Ritchie, 1972) in Hooper’s examination of cannibalism and the meat business (‘I got a real good eye for prime meat’, Drayton Sawyer asserts upon winning the cookoff). Sawyer, on the other hand, represents that most ideal of citizens in Reagan’s America, the small businessman (‘a big businessman is what a small businessman would be if only the government would get out of the way and leave him alone’, Reagan famously asserted in 1984). In another echo of Reagan’s rhetoric and policies, Sawyer rants against taxation: ‘It’s the little guy that can’t make a dime!’, he complains, ‘He pays the taxes. Small businessman gets it in the ass every time’. However, Sawyer has commercialised the trade in human meat, using the flesh from the bodies of his victims as the basis for his beloved chilli. In the caves underneath Battle Land, Stretch witnesses Leatherface preparing LG’s corpse, swapping his chainsaw for an electric carving knife which he wields in just the same way as he peels LG’s skin from his thighs, waist and face. Kevin Connor’s 1980 picture Motel Hell offered a similar parody of the meat ‘business’ (and also climaxed with a similar chainsaw duel to Hooper’s film), as did Rick Roessler’s Slaughterhouse (1987), though the Sawyer’s ‘business model’ seems arguably to be based on the relationship between ‘demon barber’ Sweeney Todd and his neighbour, piemaker Mrs Lovatt, in the Tod Slaughter Sweeney Todd: Demon Barber of Fleet Street (George King, 1936). There’s a touch of the superb Prime Cut (Michael Ritchie, 1972) in Hooper’s examination of cannibalism and the meat business (‘I got a real good eye for prime meat’, Drayton Sawyer asserts upon winning the cookoff).

Video

This is a repackaging of Arrow’s 2013 Limited Edition release, sans the second disc that included Hooper’s early feature Eggshells (from 1969). This is a repackaging of Arrow’s 2013 Limited Edition release, sans the second disc that included Hooper’s early feature Eggshells (from 1969).

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 takes up 27.6Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented uncut, with a running time of 100:33 mins, and is in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Where The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had been shot on 16mm, this sequel was filmed on 35mm colour stock. The source for this presentation was a HD master which was taken from an interpositive. The restoration work was supervised by the film’s Director of Photography Richard Kooris, who adjusted the contrast levels and performed extensive colour correction. Contrast levels are often very sharp: midtones have clear definition to them, but highlights and shadows pull away from the middle, with shadows sometimes seeming slightly ‘crushed’. The film’s photography is the opposite of the naturalistic 16mm photography of the first Texas Chain Saw Massacre; lensed by Richard Kooris, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 includes numerous scenes that feature similar coloured lighting gels (predominantly red and green) that Hooper had put to expressionistic use in his garish Eaten Alive (AKA Death Trap, 1976, the Arrow Video release of which was reviewed by us here). These vivid lighting schemes are represented here very well, and colours are mostly balanced nicely – though there are some scenes in which skintones seem very ‘hot’. A pleasing level of fine detail is present throughout, especially noticeable in close-ups of the actors, and little to no damage is present throughout. (In the US, Scream Factory released their own Special Edition Blu-ray of this film which included both this Kooris-supervised presentation and a new 2k scan from an interpositive; the latter exhibited a slightly greater level of fine detail and softer tonal curves, some people preferring it to the Kooris-supervised presentation. The truth is that, though different, both presentations are very pleasing and offer a huge step up from the previously-available home video versions of this film.) Finally, a solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, and there’s no evidence of harmful digital tinkering.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is rich and clear and shows good range, which is particularly noticeable when the film’s various chainsaws are fired up (natch). Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included too, and these are easy to read, accurate and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Audio commentary with director Tobe Hooper, moderated by David Gregory. This is a solid commentary track with Hooper recollecting the origins of the film and its production history. There are some periods of silence, but Gregory asks the right questions to keep Hooper’s memories of the picture flowing. - Audio commentary with actors Bill Moseley and Caroline Williams, and makeup effects artist Tom Savini, moderated by Michael Felsher. This is a witty track, and the participants are clearly enjoying one another’s company. The track is filled with anecdotes about the shoot, and about the processes involved in working on the picture – including the integration of Savini’s makeup effects into the production. - ‘It Runs in the Family’ (87:55). Divided into six discrete parts but with a ‘Play All’ option, this incredibly detailed documentary covers pretty much everything one would need to know about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, including the writing of the film, the designing and implementation of the special makeup effects, the casting and the reception with which the release of the completed picture was met. - ‘Still Feelin’ the Buzz’ (28:31). An interesting piece featuring input from Stephen Thrower, this looks at the film’s relationship with the original film and explores some of the themes of the picture, including some of the allusions to the Vietnam War (and how this is represented through Moseley’s character).

- ‘Cutting Moments with Bob Elmore’ (14:41). Elmore doubled for Leatherface actor Bill Johnson, and here Elmore discusses his experiences making the film – including soldiering on with the chainsaw scenes despite breaking his wrist in an accident on-set. - Alternate Opening (1:56). This alternate opening sees the film’s titles playing out against an image of woodland with the moon in the background, and underscored by a more sombre music cue. - Deleted Scenes (10:37). The deleted scenes are each prefaced by a short text introduction that tells us where they would have been placed in the finished film, had they been included. All of the scenes are sourced from poor quality VHS dupes but are fascinating nonetheless. The scenes include images from the massacre of yuppies that would have taken place in the mid-section of the picture, including the cameo from film critic Joe Bob Briggs. - Trailer (1:01). - Stills Gallery (1:25).

Overall

An often unfairly maligned film – the negative reaction of many fans largely owing to the fact that this film offers a very different experience, in tone and pretty much everything else, from the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is nevertheless by no means a neglected masterpiece. It’s a compromised picture, Cannon’s turbulent relationship with Hooper being well documented both in the on-disc extras and in the literature that has been published about the film. (Hooper’s attitude is perhaps best summed up in his cameo appearance, wearing a bull-horn cap, smoking a cigar and carrying a can of the director’s beloved Dr Pepper from which he swigs before lugging it at a group of rowdy youths in the hotel in which Lefty is staying.) However, it’s certainly an interesting film, even whilst it continues to divide viewers. Though aesthetically very different from the original picture, TCM2 extends the satire of that film (Hooper’s amplification of the humour within the script clearly a response to the fact that most people ignored the black comedy of the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre) and savages many sacred cows of the 1980s. The climax plays the evangelical hysteria of Lefty against the Reaganite rhetoric of Drayton Sawyer, arguably summing up the mid- to late-1980s as well as many other more lauded films made during that era (for example, Wall Street or RoboCop). Savini’s makeup effects are also worth singling out for mention, as they are utterly superb – even if Savini expresses dissatisfaction with how some of this footage was lit and edited. An often unfairly maligned film – the negative reaction of many fans largely owing to the fact that this film offers a very different experience, in tone and pretty much everything else, from the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is nevertheless by no means a neglected masterpiece. It’s a compromised picture, Cannon’s turbulent relationship with Hooper being well documented both in the on-disc extras and in the literature that has been published about the film. (Hooper’s attitude is perhaps best summed up in his cameo appearance, wearing a bull-horn cap, smoking a cigar and carrying a can of the director’s beloved Dr Pepper from which he swigs before lugging it at a group of rowdy youths in the hotel in which Lefty is staying.) However, it’s certainly an interesting film, even whilst it continues to divide viewers. Though aesthetically very different from the original picture, TCM2 extends the satire of that film (Hooper’s amplification of the humour within the script clearly a response to the fact that most people ignored the black comedy of the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre) and savages many sacred cows of the 1980s. The climax plays the evangelical hysteria of Lefty against the Reaganite rhetoric of Drayton Sawyer, arguably summing up the mid- to late-1980s as well as many other more lauded films made during that era (for example, Wall Street or RoboCop). Savini’s makeup effects are also worth singling out for mention, as they are utterly superb – even if Savini expresses dissatisfaction with how some of this footage was lit and edited.

Arrow’s release of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is very pleasing indeed. The presentation is solid (although some people prefer the softer contrast curves and more muted palette of the 2k interpositive scan included on the US Blu-ray release from Scream Factory) and the disc is packed with absolutely excellent contextual material. The commentary from Hooper is excellent, and the feature-length documentary is essential viewing for any fan of these films or of Hooper’s work more generally. Stephen Thrower’s piece about the themes of the picture is also very good. Though a repackaging of Arrow’s earlier Limited Edition, this single-disc Blu-ray release is a must-buy for UK viewers who for whatever reason didn’t pick up the LE when it was released in 2013. References: Muir, John Kenneth, 2002: Eaten Alive at a Chainsaw Massacre: The Films of Tobe Hooper. London: McFarland & Company Wood, Robin, 2003: Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan… and Beyond. Columbia University Press (Revised Edition)

|

|||||

|