|

|

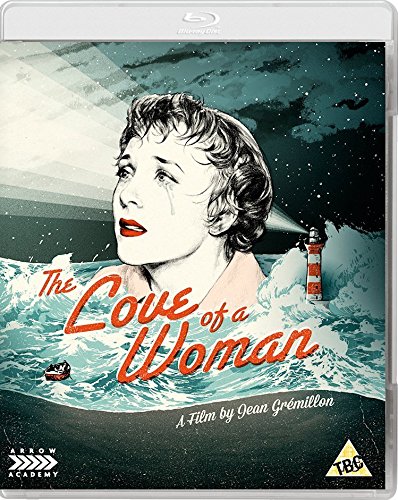

Love of a Woman (The) AKA L'amour d'une femme (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st August 2017). |

|

The Film

L’amour d’une femme (The Love of a Woman; Jean Grémillon, 1953) L’amour d’une femme (The Love of a Woman; Jean Grémillon, 1953)

Marie Prieur (Micheline Presle), a young female doctor, arrives at an island community where she is to take over the practice of an established male doctor. Marie soon discovers that she must prove herself to the community, who are initially sceptical of her abilities. She is mocked by some of the locals – mostly men. When a young girl, Aline, falls ill with pneumonia, Aline’s parents are doubtful of Marie’s ability to save the child. However, Marie proves them wrong and Aline pulls through miraculously. Marie forms a friendship with spinsterish schoolteacher Germaine Leblanc (Gaby Morlay). Leblanc has given herself completely to her profession, telling Marie that the children she teaches are her family – and so she does not regret not finding a husband and forming a family of her own. Marie also becomes romantically involved with an engineer, Andre Lorenzi (Massimo Girotti), who is in the area on a temporary contract and is due to leave soon. Initially, Marie is resistant to Andre’s advances, but eventually she warms to the man. However, as Marie and Andre grow closer, Marie is warned by Leblanc not to form any romantic attachments. As the deadline for the completion of Andre’s project looms, Andre suggests to Marie that they should marry and Marie give up her career to be a housewife. Marie becomes torn between her desire for Andre and her dedication to her career. L’amour d’une femme (The Love of a Woman) was the final film of its director, Jean Grémillon. Grémillon began his career as a film director by making documentaries before directing his first narrative feature, Maldone, in 1928. Grémillon specialised in naturalistic stories that featured a strong sense of emotional realism. Noel Burch and Genevieve Sellier frame The Love of a Woman alongside Max Ophuls Madame de… (1953) and Lola Montes (1955) as one a handful of ‘profoundly pessimistic’ films ‘which attempt to make visible both the patriarchal oppression of women and their desire to escape from it’ (Burch & Sellier, 2000: 60).  Stories about metropolitan/cosmopolitan doctors who arrive in small communities and must overcome prejudices against them by ‘proving’ themselves to their patients seem to have a perennial sense of popularity, forming the backbone of modern narratives such as the ITV television drama Doc Martin (2004-). As the doctor that Marie replaces tells her upon her arrival, the village was ‘my battlefield. I fought my thirty years war here. Now it’s your turn’. However, Marie’s battles are fought on more than one front owing to the fact that she is a woman. ‘Women have to work these days’, she tells one of the film’s other characters when she’s asked about why she has chosen to be a doctor, ‘so they may as well do a job they love’. Shortly afterwards, one of the locals tells another, in reference to Marie, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll soon put her in her place’. However, Marie soon begins to win over her patients (‘At first they resented me, but now they’re starting to call’, she observes). Stories about metropolitan/cosmopolitan doctors who arrive in small communities and must overcome prejudices against them by ‘proving’ themselves to their patients seem to have a perennial sense of popularity, forming the backbone of modern narratives such as the ITV television drama Doc Martin (2004-). As the doctor that Marie replaces tells her upon her arrival, the village was ‘my battlefield. I fought my thirty years war here. Now it’s your turn’. However, Marie’s battles are fought on more than one front owing to the fact that she is a woman. ‘Women have to work these days’, she tells one of the film’s other characters when she’s asked about why she has chosen to be a doctor, ‘so they may as well do a job they love’. Shortly afterwards, one of the locals tells another, in reference to Marie, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll soon put her in her place’. However, Marie soon begins to win over her patients (‘At first they resented me, but now they’re starting to call’, she observes).

The ‘lady doctor’ was a popular figure in literature of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries: for example, in Annie S Swan’s stories about Elizabeth Glen, M.B., which were originally published in the magazine The Woman at Home during the 1890s. These stories almost invariably featured a focus on the tension between the female doctor’s professional life and her home/romantic life (or lack thereof), with these characters often being faced with the choice of continuing their career or participating in marriage and becoming a wife; these themes are explored in detail in Tabitha Sparks’ book about this subgenre of literary fiction, The Doctor in the Victorian Novel (2016). This contrast between the private and the public is also the thematic focus of The Love of a Woman, the character of Marie being engaged in a dialogue between her dedication to her profession and her newfound love for Andre, the engineer. The Love of a Woman also has some superficial similarities with Pat Jackson’s 1951 British film White Corridors, based on Helen Ashton’s novel Yeoman Hospital and focusing on female surgeon Dr Sophie Dean (played by Googie Withers). Additionally, Grémillon’s film offers an interesting comparison with the likes of the Simon Sparrow films, with the first in the series of six big screen adaptations of Richard Gordon’s novels, Ralph Thomas’ Doctor in the House, being released only a year later in 1954.  Grémillon’s film juxtaposes Marie, the professional at the start of her career, with Leblanc, who is coming to the end of her career as a schoolteacher. Leblanc is lonely, though she claims that the children she teaches are her extended family (‘Think a man could have given me this big a family?’, she asks Marie, ‘I owe this life to my profession, Marie, and to my profession alone’); nevertheless, when Leblanc dies, the children she loves, Aline and Jeannot, sneak away from her funeral to care for their injured lamb Nenette. Marie also observes that during Leblanc’s funeral, nobody cries. Before her death, Leblanc advises Marie to leave aside her desire for a romantic relationship with Andre: instead, Leblanc argues, Marie should concentrate on establishing her career, dedicating her life to her profession rather than to romance. ‘You’re making a fool of yourself’, Leblanc tells Marie, You’re trying to ruin your situation for a passing affair’. ‘Can’t I live a little?’, Marie asks in response. ‘Yes, Marie, but there’ll be a price to pay’, Leblanc asserts, ‘You’ve done years of study; you’ll be a valuable asset. You have established yourself and you throw all that away for a wastrel’. Grémillon’s film juxtaposes Marie, the professional at the start of her career, with Leblanc, who is coming to the end of her career as a schoolteacher. Leblanc is lonely, though she claims that the children she teaches are her extended family (‘Think a man could have given me this big a family?’, she asks Marie, ‘I owe this life to my profession, Marie, and to my profession alone’); nevertheless, when Leblanc dies, the children she loves, Aline and Jeannot, sneak away from her funeral to care for their injured lamb Nenette. Marie also observes that during Leblanc’s funeral, nobody cries. Before her death, Leblanc advises Marie to leave aside her desire for a romantic relationship with Andre: instead, Leblanc argues, Marie should concentrate on establishing her career, dedicating her life to her profession rather than to romance. ‘You’re making a fool of yourself’, Leblanc tells Marie, You’re trying to ruin your situation for a passing affair’. ‘Can’t I live a little?’, Marie asks in response. ‘Yes, Marie, but there’ll be a price to pay’, Leblanc asserts, ‘You’ve done years of study; you’ll be a valuable asset. You have established yourself and you throw all that away for a wastrel’.

Meanwhile, Andre attempts to tempt Marie away from her profession, proposing marriage to her and suggesting that when they marry, Marie will no longer need to work: ‘Now you found your man, you don’t need a job’, he says. ‘But I like my job’, Marie protests gently, ‘You don’t understand: it’s much more important than that?’ ‘More important than me?’, Andre asks unsympathetically. Marie’s turning point comes at Leblanc’s funeral: the priest delivers a eulogy for the deceased, reminding the mourners that Leblanc renounced being a wife and mother ‘to raise up children who were not your own’. ‘If you are a grain of corn in a field, do not envy the poplar which reaches up to Heaven’, the priest says, ‘Remain the grain of corn. Be the seed of life’. Noticing that the mourners at the funeral do not shed a tear for the deceased Leblanc, and that two of Leblanc’s favourite pupils (Aline and Jeannot) flee from the funeral to take care of their lamb, Nenette, Marie takes the priest’s words as a suggestion that she should accept Andre’s offer.

Video

The film takes up 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The presentation is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is uncut, running for 103:07 mins. The film takes up 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The presentation is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is uncut, running for 103:07 mins.

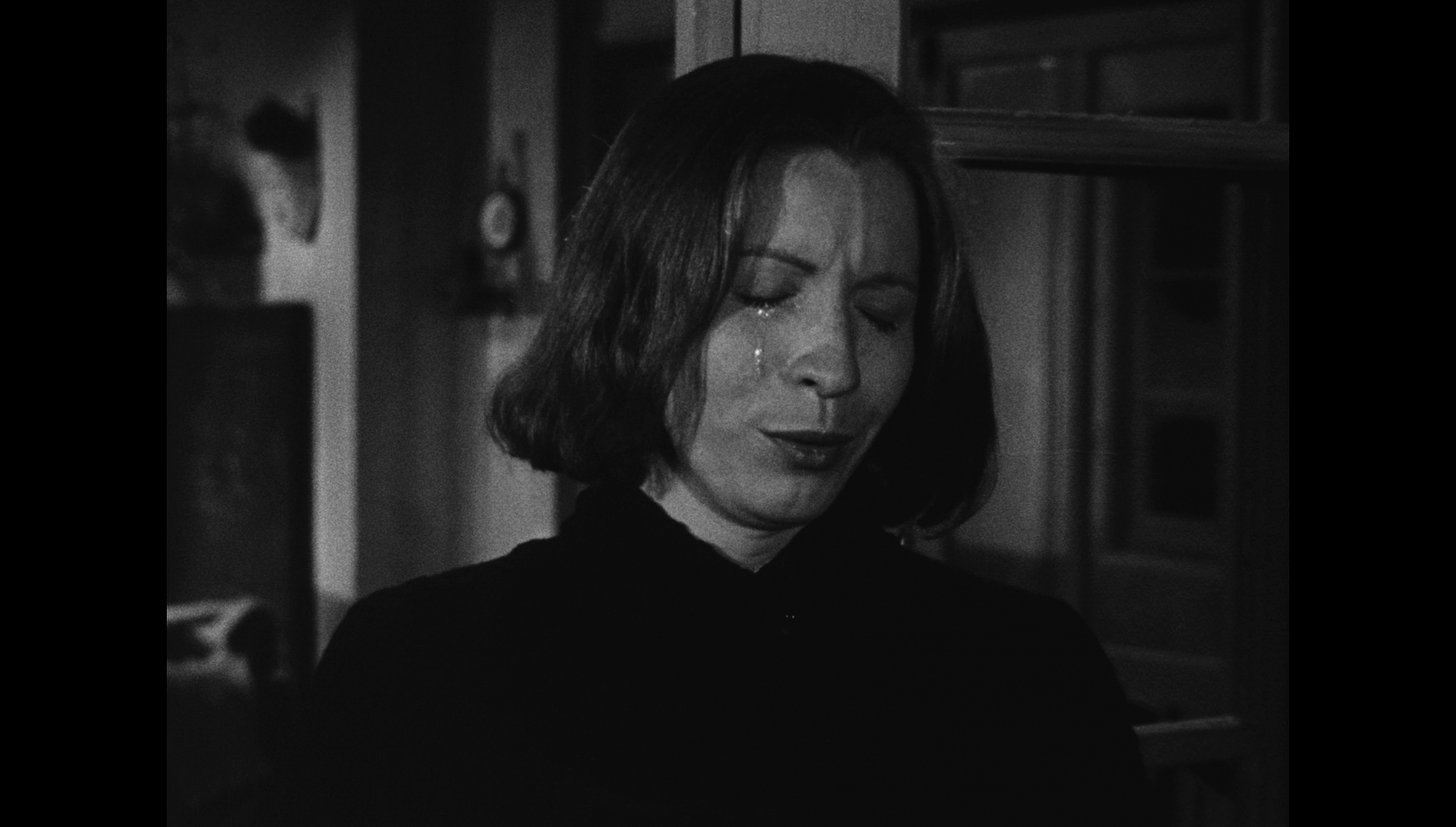

The film’s photography features much use of shorter focal lengths, including some wide-angles that are characterised by noticeable barrel distortion; and some of the wider lenses, presumably shot wide open in the low-light interiors, feature pinpoint sharpness at the centre of the composition but a noticeable softness as the image tapers off towards the edges of the frame. This is a fairly common problem with some vintage wide-angle lenses, particularly when they are shot wide open, and it must be stressed that this is a feature of the film’s original photography rather than an issue with this specific presentation. Aside from this, the photography features many studied, almost painterly compositions that at times seem to recall early still photography by the likes of William Henry Fox Talbot. Shot on 35mm monochrome stock, the film is represented exceedingly well on this HD release, with materials supplied by the rights holder. Little to no damage is present throughout the picture, and contrast levels are excellent: midtones are richly defined, and blacks are deep and rich. Highlights are evenly balanced. An equally excellent level of fine detail is present throughout the film, close-ups exhibiting an impressive sense of texture. Finally, a solid encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a very organic, film-like viewing experience.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is fine and demonstrates an adequate range with no distortion. The optional English subtitles are sometimes a little ‘loose’ and seem quite modernised in their interpretation of the French dialogue, but in terms of content they’re accurate and free from grammatical errors. (Interestingly, some of the subtleties of the French dialogue are lost in the English translation – such as Andre’s noticeable tendency to address Marie by the formal ‘vous’, rather than ‘tu’, when they are in public.)

Extras

The disc includes only one ‘extra’ feature, but it’s a very good one: ‘In Search of Jean Grémillon’ (96:09) is a feature-length documentary about the director that was made for French television in 1969. The excellent documentary reflects on Grémillon’s career and features input from some of his contemporaries, such as René Clair and actors including Micheline Presle and Pierre Brasseur. The documentary takes up approximately 15Gb of space on the disc and is in French (naturally) with optional English subtitles.

Overall

The Love of a Woman is an interesting film that taps into a subgenre that was well-established at the time of the film’s production but which has fallen by the wayside since: stories of ‘lady doctors’, torn between their careers and roles as ‘independent’ women and the patriarchal assumption that a woman’s ‘natural’ place is as a wife and mother, were popular in the late Victorian era and through the early 20th Century but perhaps seemed a little blasé during the era of Women’s Lib. These narrative paradigms continued but were subsumed into medical dramas with a more general focus, such as the BBC’s long-running Casualty (1986-). Some of the discourse about Arrow Academy’s new release of this film focuses on how forward-thinking it is, but I’m not sure that’s true: certainly, the dilemma that Marie faces can be found in the likes of Annie S Swan’s stories about Elizabeth Glenn, M.B., which were published sixty years before The Love of a Woman was made. The film perhaps seems forward-thinking to us in retrospect because the era of second-wave feminism that followed pushed such stories to one side, and now we look upon them with modern eyes that are more finely attuned to the themes explored in these types of narratives. The Love of a Woman is an interesting film that taps into a subgenre that was well-established at the time of the film’s production but which has fallen by the wayside since: stories of ‘lady doctors’, torn between their careers and roles as ‘independent’ women and the patriarchal assumption that a woman’s ‘natural’ place is as a wife and mother, were popular in the late Victorian era and through the early 20th Century but perhaps seemed a little blasé during the era of Women’s Lib. These narrative paradigms continued but were subsumed into medical dramas with a more general focus, such as the BBC’s long-running Casualty (1986-). Some of the discourse about Arrow Academy’s new release of this film focuses on how forward-thinking it is, but I’m not sure that’s true: certainly, the dilemma that Marie faces can be found in the likes of Annie S Swan’s stories about Elizabeth Glenn, M.B., which were published sixty years before The Love of a Woman was made. The film perhaps seems forward-thinking to us in retrospect because the era of second-wave feminism that followed pushed such stories to one side, and now we look upon them with modern eyes that are more finely attuned to the themes explored in these types of narratives.

Regardless, however, the story is handled in an expert fashion by Grémillon, with a strong sense of naturalism and some superb performances – particularly from Presle – which underscore the emotional content of the story without tipping it into bathos. The presentation is excellent and seems true to the original photography. The English subtitle translation is sometimes a little loose and modernised and arguably softens some of the formality of the language used in the French dialogue, but it communicates the narrative well. Furthermore, this pleasing presentation is supported by a superb archival documentary about the director. This is an excellent release. References: Burch, Noel & Sellier, Genevieve, 2000: ‘Evil Women in the Post-War French Cinema’. In: Sieglohr, Ulrike (ed), 2000: Heroines without Heroes: Reconstructing Female and National Identities in European Cinema, 1945-51. London: Cassell: 47-64 Sparks, Tabitha, 2016: The Doctor in the Victorian Novel: Family Practices. London: Routledge

|

|||||

|