|

|

Day of the Jackal (The) AKA Chacal (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th September 2017). |

|

The Film

The Day of the Jackal (Fred Zinnemann, 1973) The Day of the Jackal (Fred Zinnemann, 1973)

After a botched attempt on the life of President Charles de Gaulle that is led by Lieutenant Colonel Bastien-Thiery (Jean Sorel), motivated by de Gaulle’s decision to grant independence to Algeria, the leaders of the OAS (Organisation armée secrete) – Rodin (Eric Porter), Montclair (David Swift) and Cassin (Dennis Carley) – seek refuge in Austria. From their hideout there, the OAS decide to hire a professional assassin from outside the country to ‘hit’ de Gaulle. They commission an assassin, codenamed ‘the Jackal’ (Edward Fox), to act out this task. The Jackal appears for all intents and purposes to be an English gentleman. The Jackal visits an English village cemetery and identifies the grave of a child who, if alive, would be a similar age to the Jackal himself. The Jackal then acquires the child’s birth certificate and uses this to acquire a passport in the name of Paul Oliver Duggan. He visits Genova, paying a gunsmith (Cyril Cusack) to make a highly unique and concealable rifle, telescopic sight and silencer, and tasking a much less professional forger (Ronald Pickup) to manufacture legal documents relating to another assumed identity. The forger attempts to extort the Jackal, but the Jackal swiftly dispatches the slimy little man. Meanwhile, Colonel Rolland (Michel Auclair) is investigating the OAS, believing them to be plotting an attempt on the life of de Gaulle. Rolland and his team identify an adjutant, Wolenski (Jean Martin), who is liaising with the OAS. Rolland and his men seize Wolenski and torture him into revealing what little he knows. The OAS have their own spies, however, and task Denise (Olga Georges-Picot) with beginning an affair with a member of the cabinet, allowing them to keep track of Rolland’s investigation and stay one step ahead of him.  Commander Berthier (Timothy West) proposes Deputy Commissioner Lebel (Michael Lonsdale) as the best man to head up the investigation into the Jackal. A disarmingly quiet man, Lebel seeks the help of Caron (Derek Jacobi); working together, the pair liaise with various international criminal investigation agencies, including Scotland Yard. There, Mallinson (Donald Sinden) begins an investigation into who the Jackal might be; their investigation leads to the name of Charles Harold Calcott, a man implicated in a previous assassination attempt that took place in the Dominican Republic a few years prior. Looking at passport applications, Scotland Yard identify the Jackal’s pseudonym of Paul Oliver Duggan. Commander Berthier (Timothy West) proposes Deputy Commissioner Lebel (Michael Lonsdale) as the best man to head up the investigation into the Jackal. A disarmingly quiet man, Lebel seeks the help of Caron (Derek Jacobi); working together, the pair liaise with various international criminal investigation agencies, including Scotland Yard. There, Mallinson (Donald Sinden) begins an investigation into who the Jackal might be; their investigation leads to the name of Charles Harold Calcott, a man implicated in a previous assassination attempt that took place in the Dominican Republic a few years prior. Looking at passport applications, Scotland Yard identify the Jackal’s pseudonym of Paul Oliver Duggan.

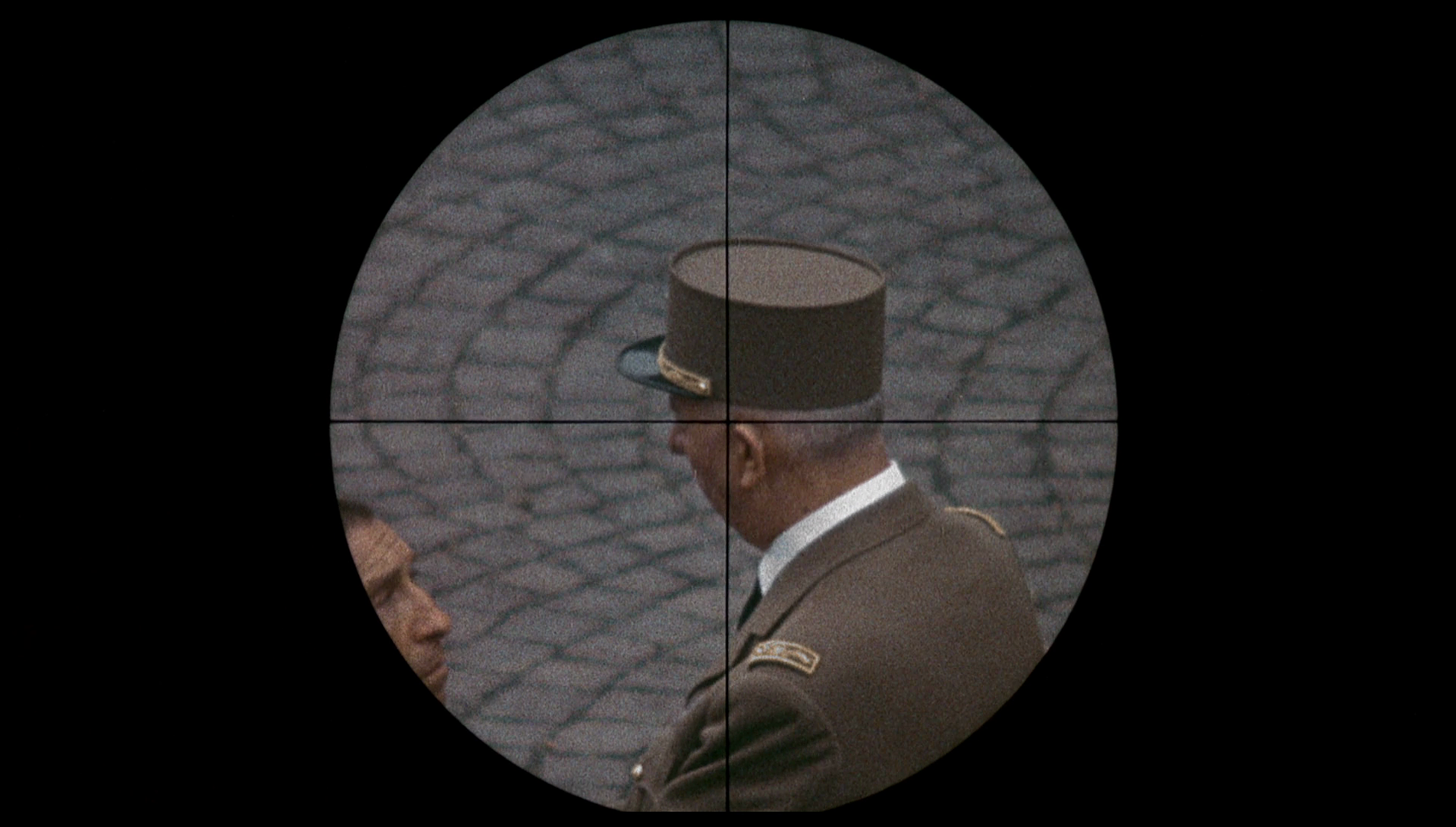

Informed by the OAS that his cover is ‘blown’, the Jackal makes use of a bored upper middle class woman, Colette de Montpelier (Delphine Seyrig). The Jackal seduces Colette before murdering her, dying his hair and emerging under yet another identity, that of a Danish teacher named Per Lundqist. The Jackal moves closer to his target, finally placing de Gaulle in the sights of his unique rifle during the Bastille Day celebrations. Following the timely popularity of Costa-Gavras’ political thriller Z in 1968, a number of subsequent French films attempted to ape Costa-Gavras’ marriage of politics, international intrigue and the conventions of the policier. In France, These films quickly attracted a pejorative label, ‘série-Z’, that was intended to invite comparisons with ‘B’ movies. These thrillers, especially those of Costa-Gavras (such as État de siège/State of Siege, 1972, and L’aveu/The Confession, 1970), were often based in real events. To some extent, these ‘série-Z’ pictures might invite comparison with the Italian cine-inchieste of directors such as Francesco Rosi, investigative films that were explicitly political and which often utilised a semi-documentary aesthetic; the cine-inchieste is often cited as being defined by pictures such as Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962) and Il caso Mattei (The Mattei Affair, 1972).  Fred Zinnemann’s The Day of the Jackal, based on Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel about a plot to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle in 1973, commissioned by the OAS and enacted by a British hired killer, blends fact and fiction. Like Forsyth’s novel, the narrative of the film begins with an account of the botched real-life attempt to assassinate de Gaulle that was carried out by French Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiery (played in the film by Jean Sorel), motivated by de Gaulle’s granting of independence to Algeria. Following this, Forsyth’s novel imagines a further, fictional, plot that involves the dissident paramilitary organisation, the OAS (Organisation armée secrete), contracting a man who claims to be a British citizen (and who adopts the codename of ‘The Jackal’), to assassinate the French President. The film makes extended use of observational montage, the absence of non-diegetic music enhancing the semi-documentary aesthetic. Zinnemann reputedly wanted to heighten the pseudo-documentary aspect of the picture by including stock footage of de Gaulle at the climax of the film, but ultimately it was decided that because the required stock footage was monochrome, it would have to be awkwardly colourised in order to be integrated into the feature, and as a result those involved in the production instead chose to have de Gaulle played by an actor (Sternberg, 1999: 212). Fred Zinnemann’s The Day of the Jackal, based on Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel about a plot to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle in 1973, commissioned by the OAS and enacted by a British hired killer, blends fact and fiction. Like Forsyth’s novel, the narrative of the film begins with an account of the botched real-life attempt to assassinate de Gaulle that was carried out by French Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiery (played in the film by Jean Sorel), motivated by de Gaulle’s granting of independence to Algeria. Following this, Forsyth’s novel imagines a further, fictional, plot that involves the dissident paramilitary organisation, the OAS (Organisation armée secrete), contracting a man who claims to be a British citizen (and who adopts the codename of ‘The Jackal’), to assassinate the French President. The film makes extended use of observational montage, the absence of non-diegetic music enhancing the semi-documentary aesthetic. Zinnemann reputedly wanted to heighten the pseudo-documentary aspect of the picture by including stock footage of de Gaulle at the climax of the film, but ultimately it was decided that because the required stock footage was monochrome, it would have to be awkwardly colourised in order to be integrated into the feature, and as a result those involved in the production instead chose to have de Gaulle played by an actor (Sternberg, 1999: 212).

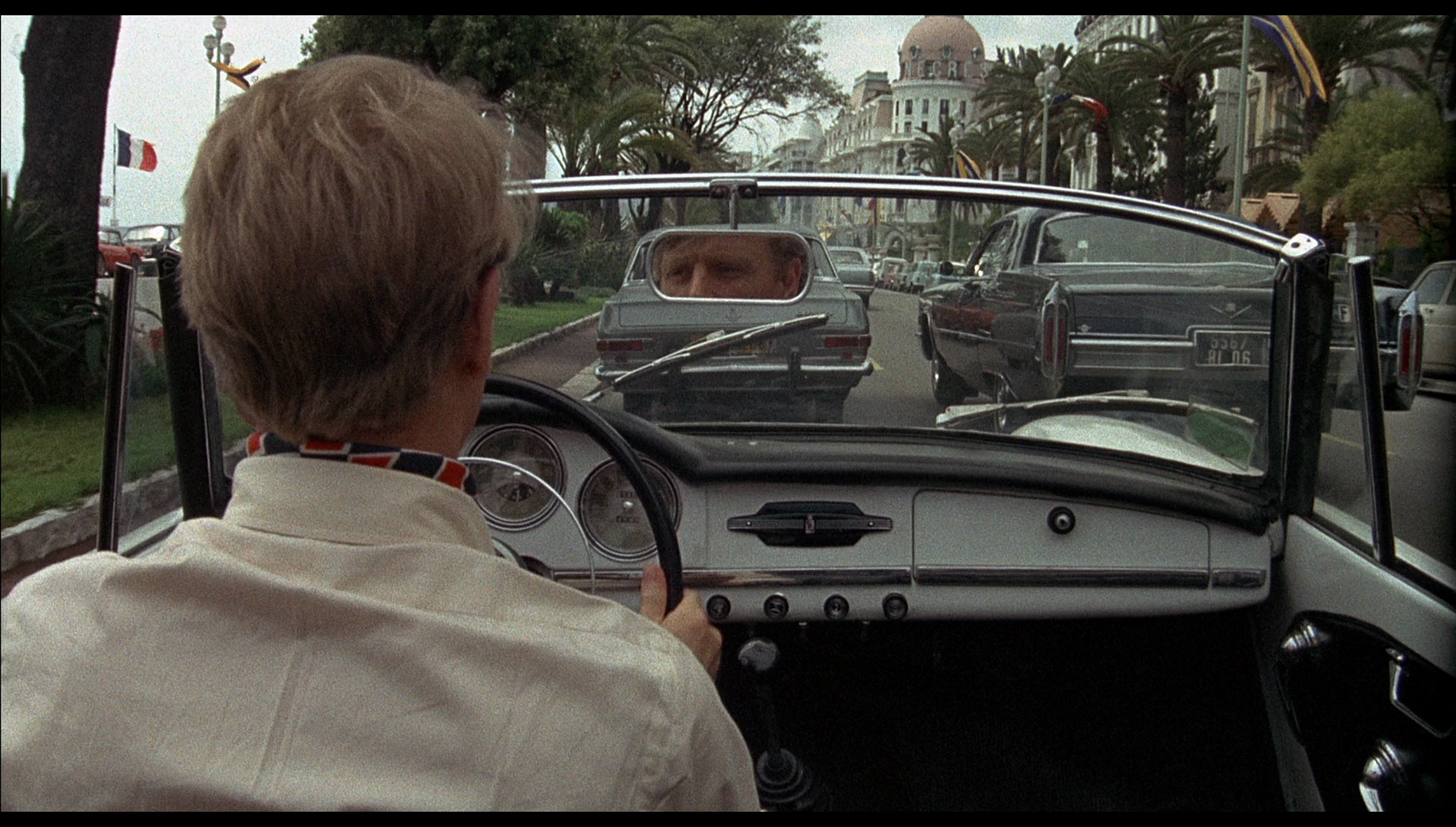

Like its European counterparts, The Day of the Jackal explored a theme of terrorism and political extremism. To all intents and purposes, Zinnemann’s picture strongly resembles the Italian cine-inchieste or the French ‘série-Z’ films. The raw material of The Day of the Jackal – the belief within the French military that by granting independence to Algeria, de Gaulle had besmirched those within the armed forces who had given their lives fighting Algerian ‘terrorists’ – formed the basis for a very similar French ‘série-Z’ picture released in the same year as Zinnemann’s film, René Gainville’s Le complot (1973). In Le complot, the OAS attempt to free General Challe, who had participated in the Algiers putsch of 1961, from prison; the ultimate goal is to spark civil war and overthrow de Gaulle, establishing a military junta. The sense of realism was emphasised by the use of location photography and photographic techniques associated with documentary filmmaking, including handheld camerawork and the employment of telephoto lenses and high angles to suggest a visual theme of surveillance. For the sequence in which the police hunt the Jackal during the Bastille Day celebrations, production took place during the real celebrations; for a brief shot, lasting less than ten seconds, featuring the old Gare Montparnasse, which had in the years since the temporal setting of the film been torn down, Zinnemann had the lower floor of the Gare Montparnass rebuilt.  The cool, clinical approach to crime – enacted by professionals – finds its corollary in the noir-tinged films polars of Jean-Pierre Melville, including the icy behaviour of hitman Jef Costello (Alain Delon) in Le samourai (1967). Colin McArthur has described Melville’s detailed explorations of specific criminal acts (often in sequences without dialogue, focusing on the actions of the characters rather than their words) in something which feels like ‘real time’ as a ‘cinema of process’ – ‘a cinema which went some way to honouring the integrity of actions by allowing them to happen in a way significantly closer to “real” time than was formerly the case in fictive, particularly Hollywood, cinema’ – and the term may arguably be used to describe Yates’ approach to both heists in this film (McArthur, 2000: 191). It’s an approach that McArthur suggests originated in Jacques Becker’s prison break picture Le trou (1960) and Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955), and which worked its way into Hollywood via the films of Michael Mann (for example, Thief, 1981). The opening sequence of The Day of the Jackal establishes this approach, depicting the slow build-up to the OAS’ failed ambush of de Gaulle’s motorcade – for which Bastien-Thiery was executed. Later sequences also employ a method of presenting action which has similarities with the cinema of process. Perhaps most memorably, when the Jackal has collected his custom-made rifle, he takes it to the countryside to practise. He draws a caricature of a human face on a watermelon and hangs it by a rope from a tree branch. The Jackal takes aim with his rifle, firing a silenced round into the watermelon. The telescopic sight is a little off. The Jackal adjusts the sight with the help of a screwdriver, then repeats the process several times until he is satisfied with the sighting of the rifle. The sequence plays out in an intimation of ‘real time’, sans any non-diegetic music. The cool, clinical approach to crime – enacted by professionals – finds its corollary in the noir-tinged films polars of Jean-Pierre Melville, including the icy behaviour of hitman Jef Costello (Alain Delon) in Le samourai (1967). Colin McArthur has described Melville’s detailed explorations of specific criminal acts (often in sequences without dialogue, focusing on the actions of the characters rather than their words) in something which feels like ‘real time’ as a ‘cinema of process’ – ‘a cinema which went some way to honouring the integrity of actions by allowing them to happen in a way significantly closer to “real” time than was formerly the case in fictive, particularly Hollywood, cinema’ – and the term may arguably be used to describe Yates’ approach to both heists in this film (McArthur, 2000: 191). It’s an approach that McArthur suggests originated in Jacques Becker’s prison break picture Le trou (1960) and Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955), and which worked its way into Hollywood via the films of Michael Mann (for example, Thief, 1981). The opening sequence of The Day of the Jackal establishes this approach, depicting the slow build-up to the OAS’ failed ambush of de Gaulle’s motorcade – for which Bastien-Thiery was executed. Later sequences also employ a method of presenting action which has similarities with the cinema of process. Perhaps most memorably, when the Jackal has collected his custom-made rifle, he takes it to the countryside to practise. He draws a caricature of a human face on a watermelon and hangs it by a rope from a tree branch. The Jackal takes aim with his rifle, firing a silenced round into the watermelon. The telescopic sight is a little off. The Jackal adjusts the sight with the help of a screwdriver, then repeats the process several times until he is satisfied with the sighting of the rifle. The sequence plays out in an intimation of ‘real time’, sans any non-diegetic music.

One of the joys of The Day of the Jackal is watching Edward Fox’s abidingly English assassin; Fox plays the Jackal as if he were a foppish prefect, using sharp wit to deflect any sense of engagement or possible commitment to the political movement which is paying him for his skills. As Neil Sinyard has suggested, Fox’s hired killer ‘is Raffles with a telescopic lens, combining the murderousness of the terrorist with the manners of the gentleman-tourist’ (Sinyard, 2003: 136). When the Jackal first meets with the OAS leaders, he listens patiently to their protestations that they are not terrorists: ‘We are not terrorists, you understand: we are patriots’, they tell him, ‘Our duty is to the soldiers who died fighting in Algeria’. Following this, the Jackal quickly deflates their sense of grandeur by underscoring their lack of efficacy in achieving their goals: ‘You see, gentlemen, not only have your efforts [to kill de Gaulle] failed, but you’ve rather queered the pitch for everyone else’, he asserts. For the Jackal, the assassination of de Gaulle is simply a technical problem which must be solved with mechanical precision. When the Jackal accepts the commission offered him by the OAS, he comes into contact with a number of other ‘professionals’, and the film contrasts the professionalism of the gunsmith who builds the Jackal’s rifle with the unprofessionalism of the forger – whose slimy nature is revealed in his first meeting with the Jackal, in which he tells the Jackal of an old army trick (swallowing cordite) to making oneself look ill or more aged in order to avoid work detail; later, he attempts to extort the Jackal by withholding the Jackal’s passport until the assassin agrees to pay him £1,000.  Like Zinnemann’s earlier High Noon (1952), The Day of the Jackal features prominent use within the mise-en-scène of clocks, like High Noon reminding us of the extent to which the film’s narrative is essentially a race against time. However, where in High Noon marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) finds the townspeople reluctant to help him in his stand against the outlaw Frank Miller and his gang, in The Day of the Jackal the hunt for the Jackal involves collaboration and co-operation across national boundaries, Scotland Yard liaising with the French police to establish the true identity of the Jackal; and the assassin is ensnared by two ‘boring’ civil servants, Level and Coran, whose most potent tool is a telephone. Like Zinnemann’s earlier High Noon (1952), The Day of the Jackal features prominent use within the mise-en-scène of clocks, like High Noon reminding us of the extent to which the film’s narrative is essentially a race against time. However, where in High Noon marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) finds the townspeople reluctant to help him in his stand against the outlaw Frank Miller and his gang, in The Day of the Jackal the hunt for the Jackal involves collaboration and co-operation across national boundaries, Scotland Yard liaising with the French police to establish the true identity of the Jackal; and the assassin is ensnared by two ‘boring’ civil servants, Level and Coran, whose most potent tool is a telephone.

Video

The film takes up just under 36Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, running for 142:36 mins. Apparently, slightly different edits of the film were prepared for different territories: Claudia Sternberg suggests that the cut of The Day of the Jackal released in France omitted the opening narration which outlines the reasons for the OAS’ bitterness towards de Gaulle; in America, the Jackal’s killing of the forger in Genova was optically censored via selective darkening of the frame (see Sternberg, op cit.: 212). The film takes up just under 36Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, running for 142:36 mins. Apparently, slightly different edits of the film were prepared for different territories: Claudia Sternberg suggests that the cut of The Day of the Jackal released in France omitted the opening narration which outlines the reasons for the OAS’ bitterness towards de Gaulle; in America, the Jackal’s killing of the forger in Genova was optically censored via selective darkening of the frame (see Sternberg, op cit.: 212).

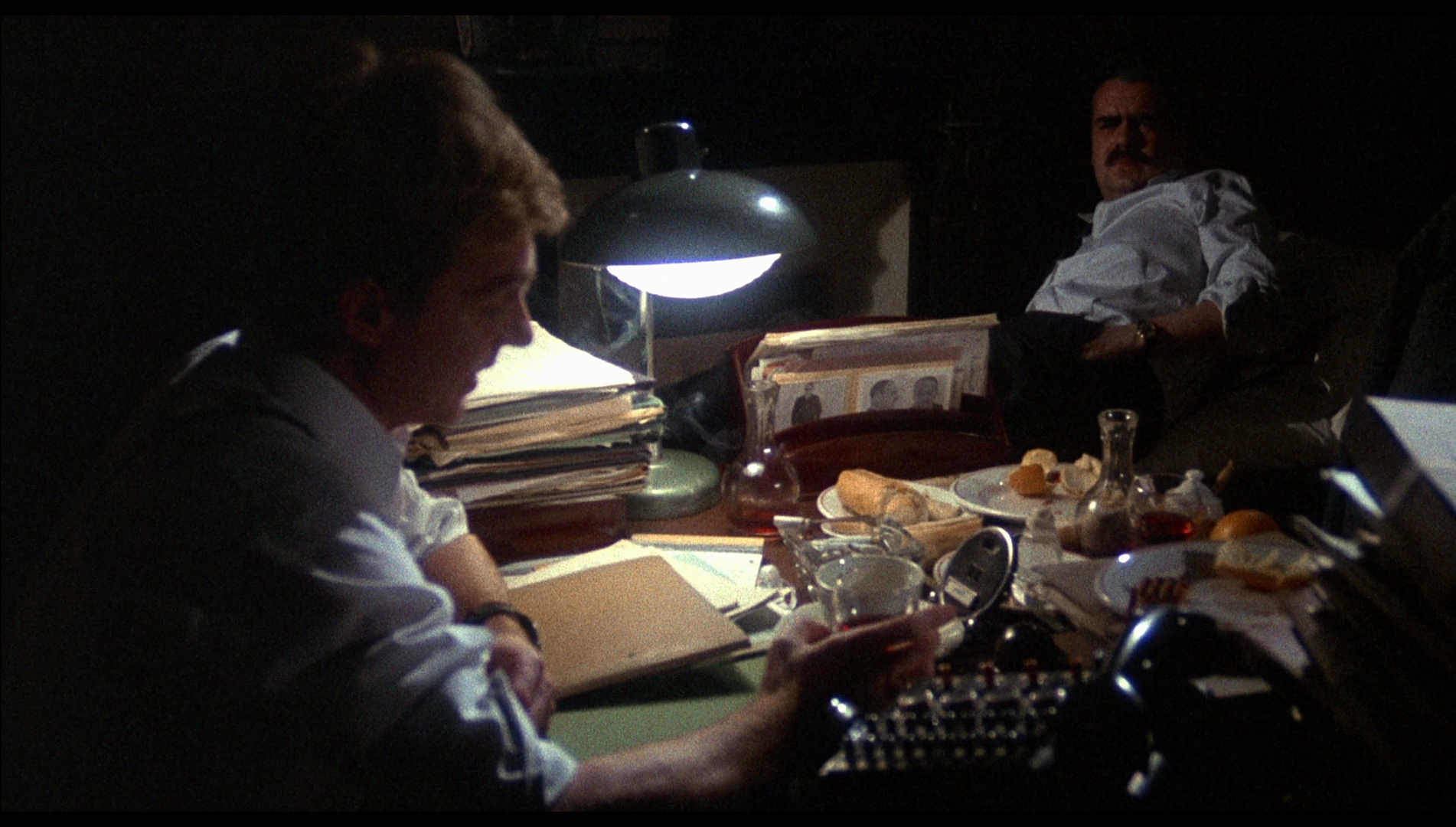

The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Little to no damage is present throughout the film. The colour 35mm photography is handled very nicely within this HD presentation. The film’s palette is mostly quite muted; colours are handled naturalistically and would seem to be true to the original intentions of the photography. Detail is good, with some pleasing fine detail present in close-ups especially, though sometimes there’s a softness that creeps into the frame and it would seem this presentation is sourced from an older master. It’s worth noting, too, that some of the close-ups of Seyrig and other actresses are shot with more flattering diffuse light, making them appear softer; and this is obviously an intentional aspect of the film’s original photography. Contrast levels are pleasing too, the harsh lighting of the exterior shots offering a sense of the blinding sun and sharp tonal curves that lead into rich, deep shadows. Midtones are clear and have a strong sense of definition. There are some wonderful shots featuring characters pinpointed by tablelamps and desklights as they labour into the night. The encode is strong, retaining the structure of 35mm film. It’s not an outstanding presentation, but it is a solid, reliable and consistent one, offering a significant improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, which is clean and clear throughout. Dialogue is always audible, and the optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are accurate in transcribing the dialogue and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘In the Marksman’s Eye’ (36:00). Neil Sinyard, the author of Fred Zinnemann: Films of Character and Conscience (and one of the most inspiring lecturers I remember from my time at university) reflects on the origins of the film in Forsyth’s source novel and discusses its significance within Zinnemann’s body of work. - Location Report (2:37). Shot during the production of the film in 1972, this footage offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the making of the picture – in particular, the construction of the old Gare Montparnasse. Comments are in French, with optional English subtitles. - Fred Zinnemann Interview (2:52). Zinnemann is interviewed on the set of the picture, in 1972. The interview is in French with optional English subtitles. - Trailer (2:04).

Overall

The Day of the Jackal is a tense modern thriller which shows the influence of the likes of Costa-Gavras’ documentary-style political thrillers. While the film may not be as lean as Costa-Gavra’s Z or State of Siege, for example, it has some wonderful moments and ideas. Fox’s performance as the enigmatic Jackal is the pivot-point of the picture, giving the film a sense of life and mystery: even at the end of the picture, the riddle of who the Jackal is remains unsolved – the police’s assumption that the Jackal is an English gentleman named Charles Calcott undercut when the real Charles Calcott returns home and chastises the police for invading ‘my bloody flat’. In another memorably amusing moment, when the French ask Scotland Yard for help in identifying the assumedly English assassin, Mallinson’s subordinate responds by declaring that ‘I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a political killer in this country. Not our style, is it?’ The Day of the Jackal is a tense modern thriller which shows the influence of the likes of Costa-Gavras’ documentary-style political thrillers. While the film may not be as lean as Costa-Gavra’s Z or State of Siege, for example, it has some wonderful moments and ideas. Fox’s performance as the enigmatic Jackal is the pivot-point of the picture, giving the film a sense of life and mystery: even at the end of the picture, the riddle of who the Jackal is remains unsolved – the police’s assumption that the Jackal is an English gentleman named Charles Calcott undercut when the real Charles Calcott returns home and chastises the police for invading ‘my bloody flat’. In another memorably amusing moment, when the French ask Scotland Yard for help in identifying the assumedly English assassin, Mallinson’s subordinate responds by declaring that ‘I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a political killer in this country. Not our style, is it?’

Arrow’s release of the picture contains a consistently good presentation of the main feature, though one which seems to be based on an older master, alongside some very good contextual material. The interview with Neil Sinyard, in particular, goes to great lengths to provide the film with a strong sense of context, both in terms of the era depicted within the narrative and within Zinnemann’s body of work as a filmmaker. This is a solid release of a perennial favourite. References: McArthur, Colin, 2000: ‘Mise-en-scène degree zero: Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967)’. In: Hayward, Susan & Vincendeau, Ginette (eds), 2000: French Film: Texts and Contexts. London: Routledge: 189-201 Sinyard, Neil, 2003: Fred Zinnemann: Films of Character and Conscience. London: McFarland & Company, Inc Sternberg, Claudia, 1999: ‘Real-Life References in Four Fred Zinnemann Films’. In: Nolletti, Arthur (ed), 1999: The Films of Fred Zinnemann: Critical Perspectives. State University of New York

|

|||||

|