|

|

The Film

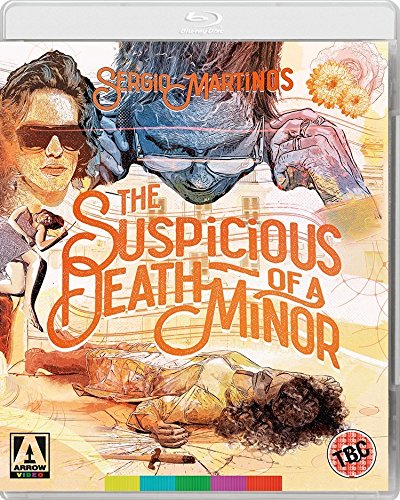

Morte sospetta di una minorenne (Suspicious Death of a Minor AKA Too Young to Die; Sergio Martino, 1975) Morte sospetta di una minorenne (Suspicious Death of a Minor AKA Too Young to Die; Sergio Martino, 1975)

In Milan, a young woman named Marisa (Patrizia Castaldi) is seen in a disagreement with her uncle, wealthy banker Gaudenzio Pesce (Massimo Girotti). Marisa visits a dance, where she flirts with a young man, Paolo (Claudio Cassinelli); however, seeing a mysterious man who wears reflective sunglasses (Roberto Posse), Marisa flees. She telephones her uncle, who refuses to take her call. She visits a pensione, looking for a man named Raimondo; however, she is pursued by the man with the sunglasses, who jumps out of the shadows and slits Marisa’s throat. The scene is investigated by a detective, Teti (Gianfranco Barra), who is humiliated when a young thief on a motorcycle snatches his watch. Meanwhile, after the police have left the scene Paolo pays a visit to the pensione and, under the threat of violence, interrogates the landlady (Fiammetta Baralla). She tells him that Marisa was associated with Il Menga, a known trafficker of minors (‘[H]e wasn’t satisfied with the usual whores: he wanted more’, she says). Paolo speaks with the thief who snatched Teti’s watch. The young man is named Giannino (Adolfo Caruso) and comes from a poor family who relocated to Milan from the south of Italy. Paolo offers Giannino a job: working together, they snatch the handbags of a number of prostitutes. Paolo is searching for information that will lead him to Il Menga, and information in a notebook that is contained in one of the snatched handbags leads Paolo to an office for temporary domestic workers. Paolo believes this to be a front for prostitution that is owned by Il Menga.  Paolo is ejected from the office but continues his investigation by engaging the services of a prostitute. Feeding her a story about being a chauffeur for a rich Arab, Paolo suggests that his ‘employer’ is interested in young girls. He offers the prostitute 500,000 lire if she can help him make contact with an organisation that will service this need. She agrees and helps him make contact with prostitute Floriana (Barbara Magnolfi). Paolo follows Floriana to a derelict house, where Floriana meets with a middle-aged man, who it turns out is Raimondo. Paolo enters and holds a gun on both Floriana and Raimondo. Raimondo turns the tables on Paolo, however, and holds a gun to Floriana’s head. Giannino enters and saves Paolo, but in the ensuing shootout but Floriana and Raimondo are killed. Waiting in the house, Paolo finds it to be visited by two men carrying a large sum of money – which, he soon realises, is the money procured by a group of kidnappers who recently held hostage the son of a wealthy industrialist named Porella. Paolo overcomes these men and takes control of the money. Paolo is ejected from the office but continues his investigation by engaging the services of a prostitute. Feeding her a story about being a chauffeur for a rich Arab, Paolo suggests that his ‘employer’ is interested in young girls. He offers the prostitute 500,000 lire if she can help him make contact with an organisation that will service this need. She agrees and helps him make contact with prostitute Floriana (Barbara Magnolfi). Paolo follows Floriana to a derelict house, where Floriana meets with a middle-aged man, who it turns out is Raimondo. Paolo enters and holds a gun on both Floriana and Raimondo. Raimondo turns the tables on Paolo, however, and holds a gun to Floriana’s head. Giannino enters and saves Paolo, but in the ensuing shootout but Floriana and Raimondo are killed. Waiting in the house, Paolo finds it to be visited by two men carrying a large sum of money – which, he soon realises, is the money procured by a group of kidnappers who recently held hostage the son of a wealthy industrialist named Porella. Paolo overcomes these men and takes control of the money.

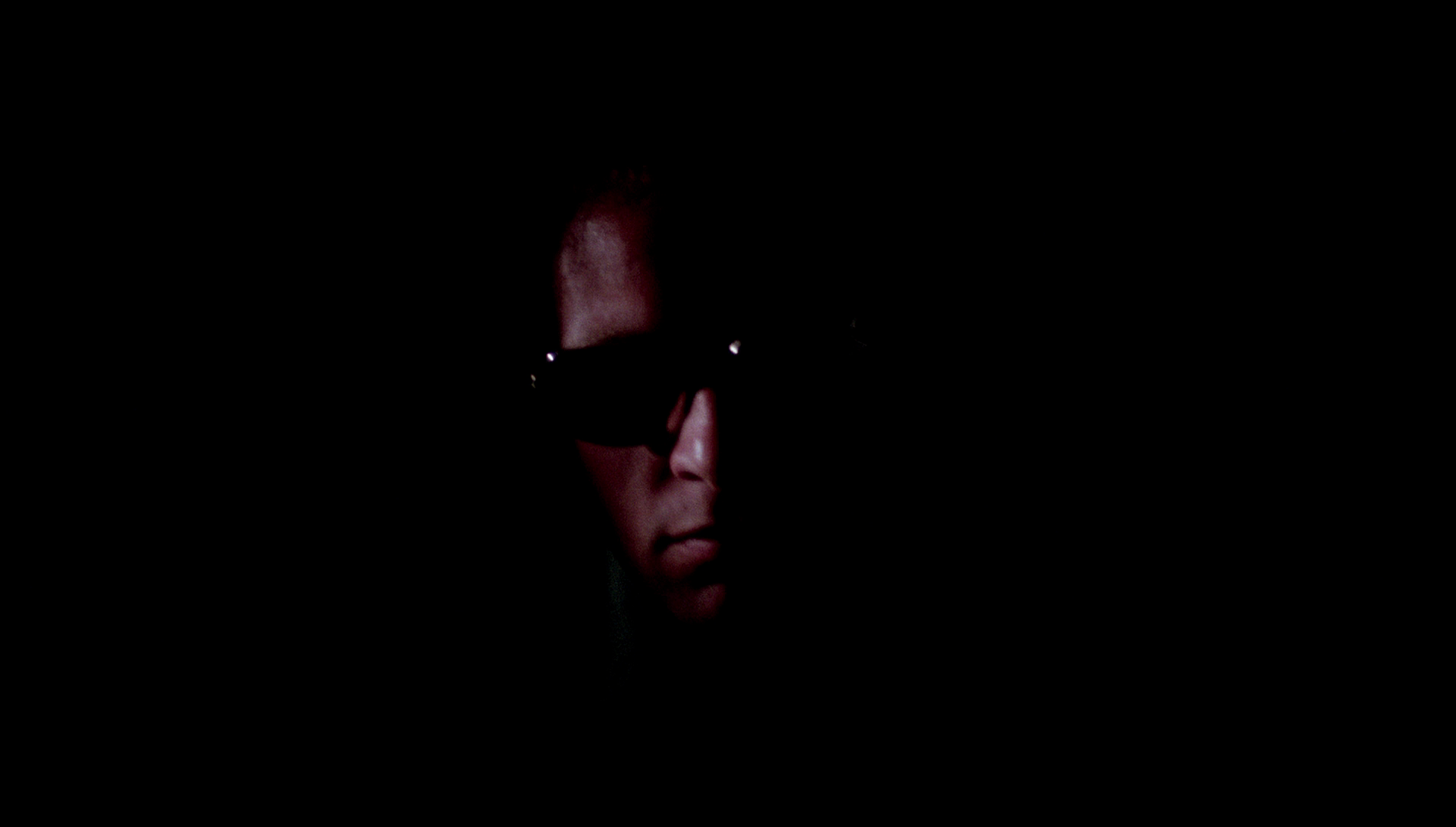

Paolo and Giannino leave the house with the money but are pursued by the police. Paolo drives to the police station, where to Giannino’s surprise Paolo reveals he is a member of a special undercover squad tasked with solving a spate of kidnappings that have been taking place in Milan. Paolo is chastised by the superintendent (Mel Ferrer) for going rogue. Paolo suggests to his boss that someone in a position of power is helping to launder the monies paid to the kidnappers in each ransom case, but the superintendent asks Paolo if he’s planning ‘to investigator or overthrow the government’. Paolo and Giannino make contact with Gloria (Jenny Tamburi), a friend of Marisa’s, who reveals to Paolo the fact that Marisa was the niece of banker Pesce. Paolo becomes convinced that Pesce is involved in both the kidnappings and the teenage prostitution racket, and he soon becomes aware that Marisa was blackmailing Pesce over the fact that Pesce, who became Marisa’s guardian following the deaths of her parents in an airplane accident, had been abusing Marisa sexually for a number of years. Paolo investigates Pesce but finds that his activities are frustrated by his superiors, who fear that Paolo will alienate Pesce and thereby draw negative attention from other powerful members of society.  Like Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films), Sergio Martino’s Morte sospetta di una minorenne (Suspicous Death of a Minor, also released in English as Too Young to Die, 1975) is a hybrid of Italian-style thriller and police procedural. Like Dallamano’s picture, Suspicious Death of a Minor also focuses on a seedy teenage prostitution racket, a plot device which crops up again and again in gialli all’italiana of the mid-1970s – for example, Carlo Lizzani’s Storie di vita e malavita—Racket della prostituzione minorile (Teenage Prostitution Racket/The Prostitution Racket) and Mario Caiano’s ...a tutte le auto della polizia... (Calling All Police Cars/The Maniac Responsible), both of which were also released in 1975. Martino’s film begins with a sequence delineating the brutal murder of a young woman, Marisa, in a dingy pensione (boarding house), establishing its narrative as an enigma plot with a classic giallo-esque killer (the sinister Robert Posse, wearing a pair of reflective sunglasses, like the killers in Luciano Ercoli’s La morte accarezza a mezzanotte/Death Walks at Midnight, 1972, and Mario Landi’s later Giallo a Venezia, 1979), before gradually evolving into a police procedural focusing on the investigation by Paolo into Marisa’s death, her association with a teenage prostitution ring, and its relationship with a spate of kidnappings that have plagued Milan. Like Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films), Sergio Martino’s Morte sospetta di una minorenne (Suspicous Death of a Minor, also released in English as Too Young to Die, 1975) is a hybrid of Italian-style thriller and police procedural. Like Dallamano’s picture, Suspicious Death of a Minor also focuses on a seedy teenage prostitution racket, a plot device which crops up again and again in gialli all’italiana of the mid-1970s – for example, Carlo Lizzani’s Storie di vita e malavita—Racket della prostituzione minorile (Teenage Prostitution Racket/The Prostitution Racket) and Mario Caiano’s ...a tutte le auto della polizia... (Calling All Police Cars/The Maniac Responsible), both of which were also released in 1975. Martino’s film begins with a sequence delineating the brutal murder of a young woman, Marisa, in a dingy pensione (boarding house), establishing its narrative as an enigma plot with a classic giallo-esque killer (the sinister Robert Posse, wearing a pair of reflective sunglasses, like the killers in Luciano Ercoli’s La morte accarezza a mezzanotte/Death Walks at Midnight, 1972, and Mario Landi’s later Giallo a Venezia, 1979), before gradually evolving into a police procedural focusing on the investigation by Paolo into Marisa’s death, her association with a teenage prostitution ring, and its relationship with a spate of kidnappings that have plagued Milan.

In the mid-1970s, the Italian thriller was trying to reinvent itself via a marriage with the then-popular Dirty Harry-style poliziesco pictures featuring rogue cops (popularised by the likes of Marino Girolami’s Roma violenta/Violent Rome, 1975). Suspicious Death of a Minor features its very own rogue cop, Paolo – though Paolo doesn’t reveal himself to be a policeman until three quarters of an hour into the picture. Until that point, Paolo seems to be on the fringes of society, acting like a vigilante or possible a member of the criminal class; he enlists the aid of petty thief Giannino to track down Il Menga and his associates. Following the discovery of the relationship between the teenage prostitution plot and a subplot involving the kidnapping of a wealthy industrialist’s young son, which Martino allows to simmer via subtle references in the dialogue and news reports seen and heard on the television and radio, Paolo and Giannino – who are in possession of the ransom money, thanks to Paolo’s investigation of the house to which he follows Floriana – are chased by the police. Paolo races through the streets – right to the police station, where the pair encounter Inspector Teti, who addresses Paolo as a colleague, much to the surprise of Giannino and the film’s audience. In challenging audience sympathies in this way, and pulling the rug from the audience in relation to our comprehension of what has taken place so far in the narrative (and Paolo’s role in it), Martino seems deliberately to reference the structure of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and the murder of Marion Crane in the shower approximately 45 minutes into the film.  The film bears some uncanny similarities with Dario Argento’s landmark thrilling all’italiana, Profondo rosso (Deep Red), also released in 1975. Luciano Michelini’s score, which features ‘prog rock’ stylings married to a soaring church organ, is remarkably similar to Goblin’s score for Argento’s picture, and almost exactly like Daria Nicolodi’s journalist Gianna Brezzi, Paolo drives around in a shonky old car with doors which fail to open correctly – necessitating, as with Gianna’s vehicle in Deep Red, entry through the sunroof. Like Deep Red – or rather, the longer Italian domestic edit of Argento’s picture rather than the abbreviated version of the film made for export to English-speaking territories – Suspicious Death of a Minor also features a disarming amount of wacky comedy. Paolo’s colleague Teti, for example, visits the scene of Marisa’s murder but shows more interest in the football pools than in his job; outside the pensione, he is robbed by Giannino, who shoots past Teti on a motorcycle. The detective with whom Teti is conversing at that moment quips that Teti should perhaps call the police. (The bumbling Teti, interestingly, physically matches the description of Hercules Poirot in the Agatha Christie novels and short stories featuring the character, so much so that in his appearance Gianfranco Barra resembles quite strikingly David Suchet in his later performances as Poirot for ITV’s long-running series.) When Paolo approaches Giannino and asks for his help, Giannino asks Paolo who he works for. ‘For MYOFB’, Paolo responds. Giannino asks what these initials stand for. ‘Mind Your Own Fucking Business’, Paolo tells him. The film also features a running gag in which Paolo repeatedly finds himself in situations in which his spectacles are broken, much like Woody Allen’s Virgil in Take the Money and Run (Allen, 1969). (Some of the humour is very near-the-knuckle, however: when Paolo asks the prostitute if she will help him make contact with an organisation that traffics in minors, she responds: ‘For 500,000, I’ll find you a toddler’!) The film bears some uncanny similarities with Dario Argento’s landmark thrilling all’italiana, Profondo rosso (Deep Red), also released in 1975. Luciano Michelini’s score, which features ‘prog rock’ stylings married to a soaring church organ, is remarkably similar to Goblin’s score for Argento’s picture, and almost exactly like Daria Nicolodi’s journalist Gianna Brezzi, Paolo drives around in a shonky old car with doors which fail to open correctly – necessitating, as with Gianna’s vehicle in Deep Red, entry through the sunroof. Like Deep Red – or rather, the longer Italian domestic edit of Argento’s picture rather than the abbreviated version of the film made for export to English-speaking territories – Suspicious Death of a Minor also features a disarming amount of wacky comedy. Paolo’s colleague Teti, for example, visits the scene of Marisa’s murder but shows more interest in the football pools than in his job; outside the pensione, he is robbed by Giannino, who shoots past Teti on a motorcycle. The detective with whom Teti is conversing at that moment quips that Teti should perhaps call the police. (The bumbling Teti, interestingly, physically matches the description of Hercules Poirot in the Agatha Christie novels and short stories featuring the character, so much so that in his appearance Gianfranco Barra resembles quite strikingly David Suchet in his later performances as Poirot for ITV’s long-running series.) When Paolo approaches Giannino and asks for his help, Giannino asks Paolo who he works for. ‘For MYOFB’, Paolo responds. Giannino asks what these initials stand for. ‘Mind Your Own Fucking Business’, Paolo tells him. The film also features a running gag in which Paolo repeatedly finds himself in situations in which his spectacles are broken, much like Woody Allen’s Virgil in Take the Money and Run (Allen, 1969). (Some of the humour is very near-the-knuckle, however: when Paolo asks the prostitute if she will help him make contact with an organisation that traffics in minors, she responds: ‘For 500,000, I’ll find you a toddler’!)

In his book Italian Crime Filmography, 1968-1990, Roberto Curti notes that Suspicious Death of a Minor was originally to have been titled Milano violenta (‘Violent Milan’), but this title was eventually used by another film directed by Mario Caiano in 1976 (and released in English territories as Bloody Payroll and Commando Terror), a picture which also featured Claudio Cassinelli in its cast (Curti, 2013: 152). The film’s writer Ernesto Gastaldi felt that the film didn’t work as well as it perhaps should have, admitting that it may have been ‘tired from the start since it was my own story’ and Martino ‘didn’t manage to give the film a decisive shot-in-the-arm’ (Gastaldi, quoted in ibid.). Ultimately, ‘It’s likely there were too many films of that kind during this time’ (Gastaldi, quoted in ibid.).

Video

The presentation of the main feature takes up approximately 30Gb of space on a dual-layered disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation of the main feature takes up approximately 30Gb of space on a dual-layered disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

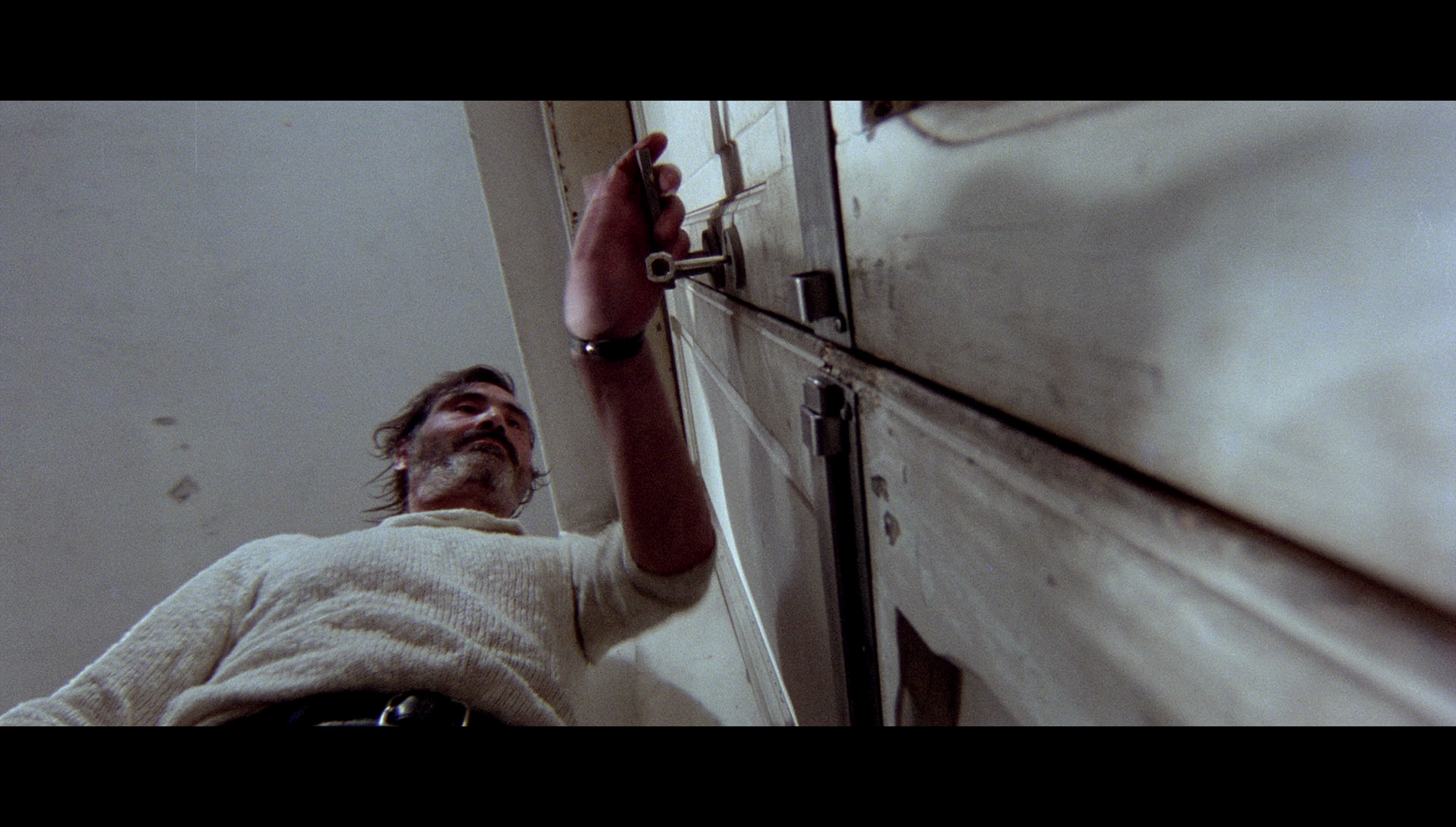

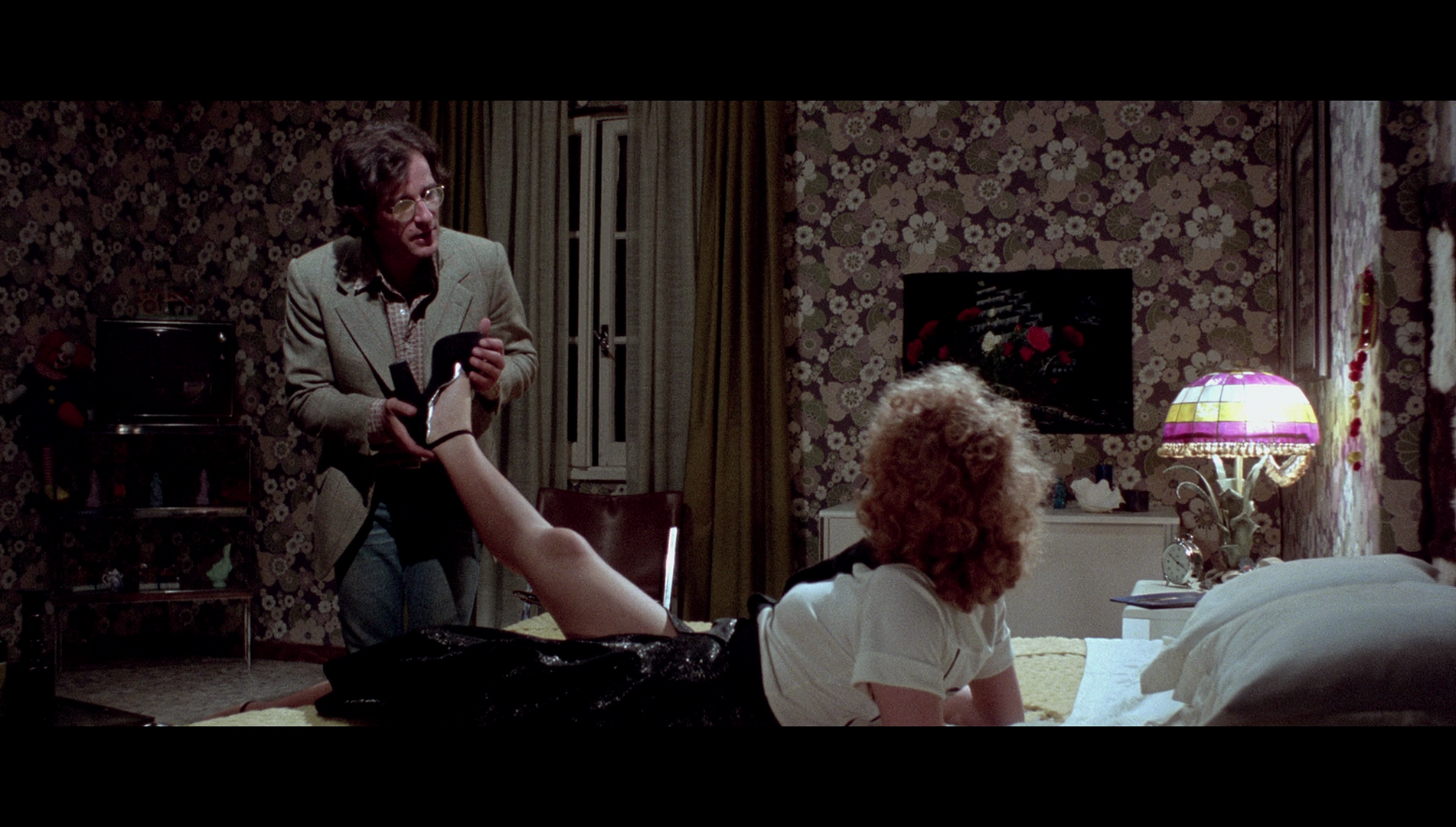

Shot in Techniscope, Suspicious Death of a Minor is presented here in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, and with a running time of 100:24 mins. As with other Techniscope pictures, the film was made using spherical lenses. Techniscope and similar 2-perf widescreen processes were cost-saving in the sense that they enabled the production of a widescreen image without the use of expensive anamorphic lenses, and by reducing the size of each frame by half (from 4-perforations to 2-perforations) halved the negative costs involved in making a film. (However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by more expensive lab costs, which for Techniscope productions steadily increased throughout the 1970s; this is sometimes cited as one of the reasons why Techniscope became less popular during the late 1970s and early 1980s.) Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)  This presentation of Suspicious Death of a Minor is a new 2k restoration based on the film’s negative. By going back to the negative, Arrow’s presentation has a greater resemblance to Techniscope films of the 1960s and early 1970s, printed using the due transfer process, rather than the standard Kodak colour printing process used for Techniscope pictures made during the mid/late 1970s. Blacks are deep and rich, and the grain structure is more muted than late-era Techniscope pictures which had been printed via the production of a dupe negative. The film’s photography makes insistent use of shorter focal lengths, strong depth of field evident throughout the film, including in many low-light interior scenes. The presentation on this Blu-ray disc features an impressive level of detail, though there’s a very slightly unnatural smoothness to some of the skin textures in tight close-ups. Contrast is good: as noted above, contrast levels seem commensurate with Techniscope pictures during the era of the dye transfer process, with deep blacks and very finely balanced midtones. Colours are consistent throughout the picture, though there’s a slight bias towards yellow in some scenes (eg, in the opening scene, the white of one of the cars on the road isn’t empirical white but has instead a very slight hue of yellow) and reds are sometimes a little ‘hot’. Damage is minimal, though in a couple of shots (eg, a long shot of the house that the kidnappers are using as their FOB) there’s some noticeable damage to the emulsions. (This looks like water/humidity damage; see the large frame grabs immediately below.) Finally, a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. This presentation of Suspicious Death of a Minor is a new 2k restoration based on the film’s negative. By going back to the negative, Arrow’s presentation has a greater resemblance to Techniscope films of the 1960s and early 1970s, printed using the due transfer process, rather than the standard Kodak colour printing process used for Techniscope pictures made during the mid/late 1970s. Blacks are deep and rich, and the grain structure is more muted than late-era Techniscope pictures which had been printed via the production of a dupe negative. The film’s photography makes insistent use of shorter focal lengths, strong depth of field evident throughout the film, including in many low-light interior scenes. The presentation on this Blu-ray disc features an impressive level of detail, though there’s a very slightly unnatural smoothness to some of the skin textures in tight close-ups. Contrast is good: as noted above, contrast levels seem commensurate with Techniscope pictures during the era of the dye transfer process, with deep blacks and very finely balanced midtones. Colours are consistent throughout the picture, though there’s a slight bias towards yellow in some scenes (eg, in the opening scene, the white of one of the cars on the road isn’t empirical white but has instead a very slight hue of yellow) and reds are sometimes a little ‘hot’. Damage is minimal, though in a couple of shots (eg, a long shot of the house that the kidnappers are using as their FOB) there’s some noticeable damage to the emulsions. (This looks like water/humidity damage; see the large frame grabs immediately below.) Finally, a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with the option of watching the film in either Italian or English. Both tracks are LPCM 1.0 mono. Audio options can’t be changed ‘on the fly’: the viewer must return to the main menu and restart the film in order to switch between the two language tracks. Both tracks are similar in their qualities and characteristics, offering a good sense of range and depth without distortion or any other issues. The Italian track is accompanied by optional English subtitles, and the English track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The Italian dialogue is filled with slang terms, which the English subtitles do a great job of translating into equivalent English expressions. Subtitles are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - An audio commentary with Troy Howarth. In a breathless track, Howarth discusses the declining popularity of Italian thrillers in the mid-1970s and reflects on this film’s relationship with the giallo all’italiana. He talks about the work of Martino and the film’s cast, and discusses the structure of the picture and its avoidance of the paradigms of the whodunit. - ‘Violent Milan’ (42:57). In a new and very thorough interview (which uses the English translation of the film’s original title), director Sergio Martino reflects on Suspicious Death of a Minor and its role within his body of work. The film’s title was changed by the producers, he says, so that it could be marketed as something closer to a giallo all’italiana rather than a poliziesco/action film. Martino discusses the writing of the film and his relationship with Ernesto Gastaldi. He also talks about the production and the film’s cast, especially Mel Ferrer. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - The film’s trailer (3:27).

Overall

Sergio Martino’s Suspicious Death of a Minor is an entertaining though, ahem, minor picture in the director’s filmography. Its fusion of elements of the Italian-style thriller and the poliziesco all’italiana is a sign of the times in which it was made, an era in which the thrilling/giallo all’italiana saw a waning popularity concomitant with a rise in the popularity of ‘rogue cop’ poliziesco pictures. Like a number of films made in the same year (and the years surrounding) Suspicious Death of a Minor marries elements of the giallo all’italiana with the poliziesco paradigm, in an attempt to breathe new life into a formula/style (I hesitate to say genre, as like film noir the Italian-style thriller is arguably more a ‘style’ than a distinct genre in and of itself) of which contemporary Italian audiences were becoming tired. It also adds a dose of bawdy humour to the proceedings. (Again, it’s not alone in this: many of its contemporaries did the same.) The result is a film that feels unfocused, although the chance it takes in terms of the plot twist regarding Paolo’s identity seems to work very well. Sergio Martino’s Suspicious Death of a Minor is an entertaining though, ahem, minor picture in the director’s filmography. Its fusion of elements of the Italian-style thriller and the poliziesco all’italiana is a sign of the times in which it was made, an era in which the thrilling/giallo all’italiana saw a waning popularity concomitant with a rise in the popularity of ‘rogue cop’ poliziesco pictures. Like a number of films made in the same year (and the years surrounding) Suspicious Death of a Minor marries elements of the giallo all’italiana with the poliziesco paradigm, in an attempt to breathe new life into a formula/style (I hesitate to say genre, as like film noir the Italian-style thriller is arguably more a ‘style’ than a distinct genre in and of itself) of which contemporary Italian audiences were becoming tired. It also adds a dose of bawdy humour to the proceedings. (Again, it’s not alone in this: many of its contemporaries did the same.) The result is a film that feels unfocused, although the chance it takes in terms of the plot twist regarding Paolo’s identity seems to work very well.

Perhaps surprisingly, however, unlike some of the other similar films that were released at about the same time (such as What Have They Done to Your Daughters? and Calling All Police Cars), Suspicious Death of a Minor is remarkably tame in its imagery – barring a couple of moments of violence (the cruel opening murder of Marisa sets a tone for the picture that subsequent sequences seem consciously to avoid) and some brief nudity (when Paolo enlists the services of a prostitute). Arrow’s presentation of the film is very good, the 2k restoration from the negative offering a presentation that has more similarities with Techniscope pictures of the dye transfer era than those of the mid/late 1970s. It’s a pleasing presentation, some fleeting damage to the source materials aside. It is also accompanied by some very good contextual material. In particular, the interview with Sergio Martino is incredibly indepth and informative. References: Curti, Roberto, 2013: Italian Crime Filmography: 1968-1980. London: McFarland

|

|||||

|