|

|

Season of the Witch AKA Hungry Wives AKA Jack's Wife (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd November 2017). |

|

The Film

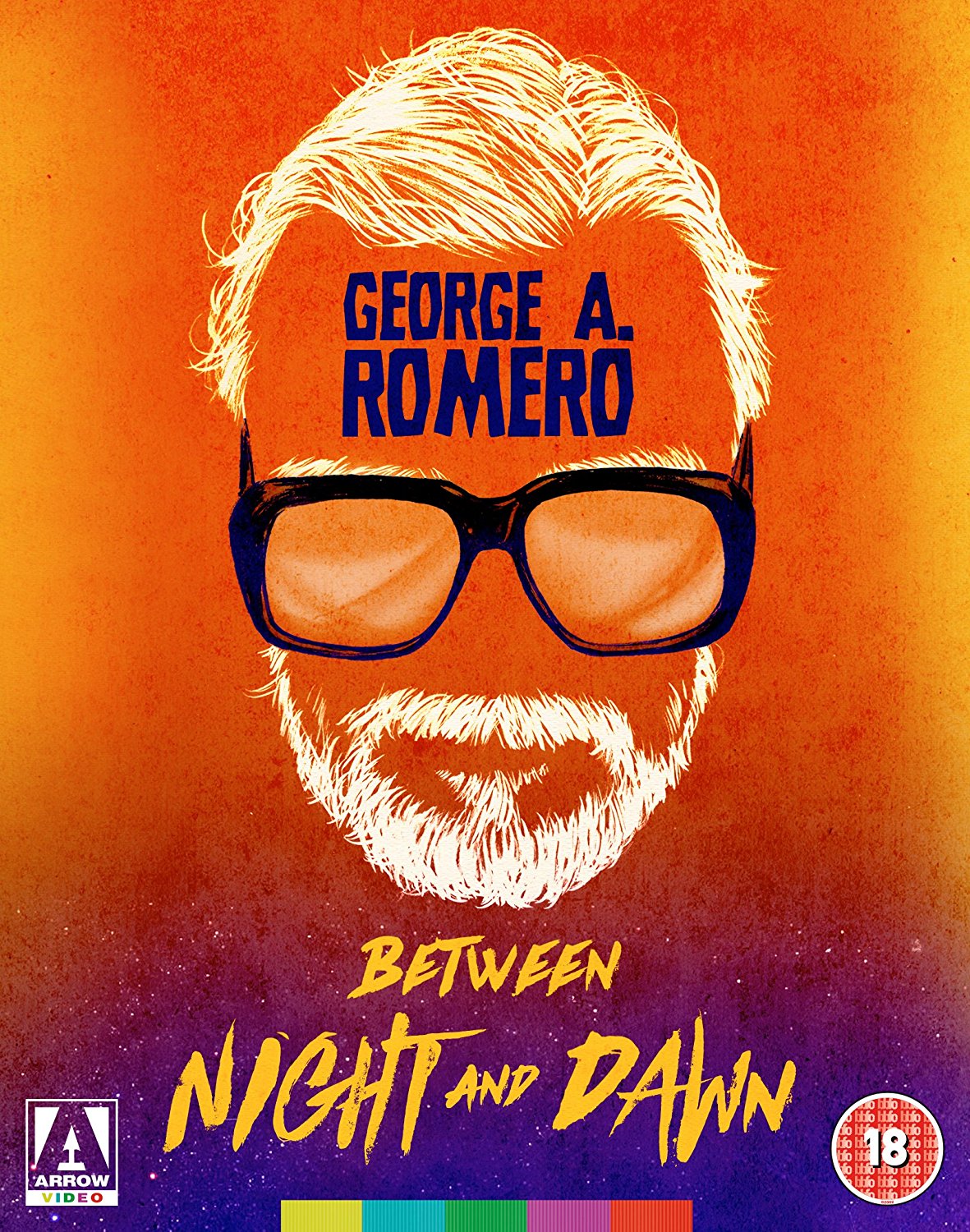

George A Romero: Between Night and Dawn  There’s Always Vanilla (1971) There’s Always Vanilla (1971)

Chris (Ray Laine) tells his story to-camera, his narration completed by extended flashbacks to the events under discussion. ‘If you can dig it’, he begins, ‘the whole thing was like that machine [….] Everything just going round and round’. The machine in question is, we are shown, a work of art presented in a city centre: catching the wind, the machine’s various appendages rotate seemingly without end. In cinema verite style, various people who pass the machine are asked about what it represents to them, some valuing it as a work of art and others deriding it as a waste of time and energy. Chris is a Vietnam veteran and session musician who lacks direction in his life. Looking for what her terms ‘a new thing’, Chris leaves the city and returns to his hometown. Chris’ journey is intercut with the shooting of a television commercial for a brand of beer. The commercial stars Lynn Harris (Judith Streiner, nee Ridley), who attracts the attentions of sleazy producer Michael Dorian (Richard Ricci). Chris encounters his father, Roger (Roger McGovern); the pair haven’t seen each other in three years. Together, Chris and Roger visit a go-go club where Chris asks one of the dancers, Sam (Louise Sahene), about the whereabouts of his ex-wife Terri ‘Terrific’ (Johanna Lawrence). After hours, Chris and Roger go with Sam to Terri’s place, and they all smoke marijuana. During the night, the philandering Roger sleeps with Sam.  In the morning, Chris asks Terri ‘Where’s the kid?’ Chris, it seems, is a father – though neither Chris nor Terri are sure whether Chris is the biological father of the boy, who is named Chris Jr (Christopher Priore). Later, as Chris says goodbye to Roger, he’s knocked to the floor by Lynn, who is in a rush. Chris offers Lynn a lift to her destination, and the pair quickly bond. They sleep together, though both express doubts about any possible future relationship. In the morning, Chris asks Terri ‘Where’s the kid?’ Chris, it seems, is a father – though neither Chris nor Terri are sure whether Chris is the biological father of the boy, who is named Chris Jr (Christopher Priore). Later, as Chris says goodbye to Roger, he’s knocked to the floor by Lynn, who is in a rush. Chris offers Lynn a lift to her destination, and the pair quickly bond. They sleep together, though both express doubts about any possible future relationship.

The next day, whilst Lynn is at work, Chris buys a typewriter and some marijuana. When Lynn returns to her flat, Chris claims that he’s working on ‘my first novel’. However, soon Lynn becomes frustrated with Chris’ lack of direction in life and presses him into applying for a degree course. In an attempt to get Lynn off his back, Chris applied for a job writing advertising copy. He gets the job but sees himself as ‘selling out’ and leaves it. Meanwhile, Lynn discovers that she is pregnant and asks Dorian if he can help her to arrange a backstreet abortion. After a decade of making short films and commercials, George A Romero struck proverbial gold with his first feature film, Night of the Living Dead, in 1968. In 1971, Romero followed that picture with a very different film, There’s Always Vanilla. Though there was overlap in terms of cast and personnel, as there would be throughout many of Romero’s subsequent films (and in particular, the three pictures included in this boxed set, which also contains 1972’s Jack’s Wife/Season of the Witch and 1973’s The Crazies), There’s Always Vanilla is in its narrative content as different as could be from Night of the Living Dead. In interview, Romero suggested that following Night of the Living Dead he ‘went through a paranoid phase of not wanting to be a horror moviemaker’, and this is what resulted in the production of There’s Always Vanilla (Romero, quoted in Yakir, 1977: 48).  Romero’s second feature offers a tale of listless youth and social issues of the day (generational struggles, casual sex, abortion). Chris, it seems, drifts from place to place and job to job, finding it impossible to settle down and commit to any particular lifestyle. He is unsure whether he is Chris Jr’s father, though he is attracted to the concept of being a parent. He has left Terri and Chris Jr, returning to them out of the blue. ‘If you’re not here when I wake up, I’ll see you again in another couple of years’, Terri tells him, ‘You spend your whole life running away from your past. How come you always wind up back here?’ Chris has no answer to this question. Romero’s second feature offers a tale of listless youth and social issues of the day (generational struggles, casual sex, abortion). Chris, it seems, drifts from place to place and job to job, finding it impossible to settle down and commit to any particular lifestyle. He is unsure whether he is Chris Jr’s father, though he is attracted to the concept of being a parent. He has left Terri and Chris Jr, returning to them out of the blue. ‘If you’re not here when I wake up, I’ll see you again in another couple of years’, Terri tells him, ‘You spend your whole life running away from your past. How come you always wind up back here?’ Chris has no answer to this question.

Coming at the tail end of 1960s counterculture, the film suggests that youth protests have achieved very little: as Chris’ father tells him towards the end of the picture, all the choices possible in one’s life may be compared to a visit to an ice cream parlour filled with exotic flavours, in which one always finds oneself falling back on a tried and tested favourite to the extent that, if it isn’t available, one becomes incredibly frustrated. ‘There’s always vanilla’ is the pithy advice Chris’ father presents to his son, capped off by Roger’s assertion early in the picture that ‘You’d better come down out of those clouds, boy, or you’re not going to be worth the powder to blow you to hell’. The protagonist’s informal, spontaneous to-camera address and the climactic, traumatic backstreet abortion sequence make the picture feel very much like an Americanised version of Lewis Gilbert’s 1966 adaptation of Bill Naughton’s play Alfie. There’s Always Vanilla also casts a sly glance at the world of television commercials – a world that Romero and his collaborators had direct experience of – and framed these as indexical of the modern world’s obsession with commodifying all aspects of life. ‘Isn’t that cheating?’, Lynn asks her producer on the set of the beer commercial. ‘Cheating?’, he asks in response. ‘Making the beer look better than it actually looks’, Lynn clarifies. ‘All of our salaries […] depend upon that beer’, the producer reminds her, ‘and we’re all here to make that beer look as good as we possibly can’. Later, when Lynn criticises commercials and questions her involvement in them, the producer attempts to allay her fears by comparing commercials with daydreaming: both, he suggests, offer a distraction from ‘bad news’. As if to hammer this point home, Chris applies for a job writing copy for ads; scoring the interview, he offers all kinds of corporate bullshit to his prospective employers, scoring the job but ultimately expressing severe disappointment with it. ‘How can I place any value in a thing like that?’, Chris asks in a to-camera address, ‘I went in there and fed those people horseshit, and they offered me the job’.  In addition, Romero employs some Godard-esque avant-garde editing techniques in several sequences, cross-cutting between Chris and Lynn having sex and the shooting of a television commercial. By cross-cutting between these two actions, Romero suggests some sort of similarity between them. Chris and Lynn’s sexual tryst is as cold, mechanical and cynically exploitative as the television commercial being shot in the studio – much like, in D H Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Mellor’s assertion that ‘It’s all this cold-hearted fucking that is death and idiocy’ refers both to his purely sexual relationship with Lady Chatterley and, more broadly, to the ‘fucking’ that the working-class experience from their employers and ‘masters’. Lynn expresses her frustrations with her work in commercials to her mother (Eleanor Schirra): ‘I just get so sick of sometimes standing around, day after day, turning this way and that way, and either sweating to death under the hot lights or trying to get excited over a lousy glass of beer’, she says, adding that ‘It’s so frustrating’. ‘What do you know about frustration?’, her mother asks Lynn. ‘Maybe I’m just cut out to be a wife and mother’, Lynn offers. ‘Marriage’, her mother scoffs, ‘Look what marriage did to me’. It’s an offhand moment, but it bleeds nicely into the beginning of Romero’s next picture, Jack’s Wife (listed in this boxed set under its more common title, Season of the Witch). By the end of There’s Always Vanilla, Chris and Lynn have failed to ‘connect’ and Lynn has been through a traumatic experience with a group of backstreet abortionist. The film casts a cynical eye upon the ‘liberatory’ values of late-1960s counterculture, suggesting that these have not benefitted anybody and that ‘selling out’ is inevitable. In addition, Romero employs some Godard-esque avant-garde editing techniques in several sequences, cross-cutting between Chris and Lynn having sex and the shooting of a television commercial. By cross-cutting between these two actions, Romero suggests some sort of similarity between them. Chris and Lynn’s sexual tryst is as cold, mechanical and cynically exploitative as the television commercial being shot in the studio – much like, in D H Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Mellor’s assertion that ‘It’s all this cold-hearted fucking that is death and idiocy’ refers both to his purely sexual relationship with Lady Chatterley and, more broadly, to the ‘fucking’ that the working-class experience from their employers and ‘masters’. Lynn expresses her frustrations with her work in commercials to her mother (Eleanor Schirra): ‘I just get so sick of sometimes standing around, day after day, turning this way and that way, and either sweating to death under the hot lights or trying to get excited over a lousy glass of beer’, she says, adding that ‘It’s so frustrating’. ‘What do you know about frustration?’, her mother asks Lynn. ‘Maybe I’m just cut out to be a wife and mother’, Lynn offers. ‘Marriage’, her mother scoffs, ‘Look what marriage did to me’. It’s an offhand moment, but it bleeds nicely into the beginning of Romero’s next picture, Jack’s Wife (listed in this boxed set under its more common title, Season of the Witch). By the end of There’s Always Vanilla, Chris and Lynn have failed to ‘connect’ and Lynn has been through a traumatic experience with a group of backstreet abortionist. The film casts a cynical eye upon the ‘liberatory’ values of late-1960s counterculture, suggesting that these have not benefitted anybody and that ‘selling out’ is inevitable.

Though structurally and dramatically, There’s Always Vanilla is as listless as its protagonist, veering from comedy to tragedy clumsily and unsure of whether it’s a drama or domestic horror picture, the film features some strong, naturalistic performances from its cast. The film ends, ironically, on the finished beer commercial which stars Lynn: it’s a commercial that foregrounds the gender stereotypes (macho male, submissive woman) that the main narrative of There’s Always Vanilla has spent so much time challenging and deflating.

Season of the Witch (1972) Season of the Witch (1972)

Bored and sexually frustrated in her marriage to husband Jack (Bill Thurnhurst), suburban housewife Joan Mitchell (Jan White) makes regular visits to her psychiatrist, Dr Miller (Neil Fisher), about her strange and vivid nightmares. During a house party, Joan is engaged in a conversation by some of her friends and neighbours about a shared acquaintance, Marion (Ginger Greenwald), who is associated with a coven. Marion is treated with scorn by the other housewives, though Joan’s interest in the occult has been piqued and she is introduced to Marion by Shirley (Ann Muffly). Later, Joan is introduced to Gregg (Ray Laine), the boyfriend of Jack and Joan’s daughter Nikki (Joedda McClain). Gregg suggests that witchcraft is simply a form of autosuggestion, proving his point by convincing Shirley that a regular cigarette is in fact a marijuana joint. Validating Gregg’s argument, the naïve Shirley appears to ‘get high’. Joan chastises Gregg for this cruel and manipulative stunt. However, returning to her house after taking Shirley home, Joan overhears Nikki having sex with Gregg. Uncomfortable with the situation and clearly unsure what to do, Joan retreats to her bedroom and tries to ignore the sounds. Embarrassed by the realisation that her mother overheard her having sex, Nikki confronts Joan angrily before running away from home. When Jack finds out, he chastises Joan for letting ‘Your own goddamned daughter [get] balled in the next room, and you go with it because you didn’t know how to handle it. What the hell is that? I’ll tell you how to handle it. You kick some ass, dammit! You kick some ass’.  Joan decides to ask Gregg if he knows where Nikki is. Gregg tells Joan he doesn’t, and he begins to flirt with Joan, referring to her as ‘Mrs Robinson’ (in an overt reference to Charles Webb’s 1963 novel The Graduate). Joan visits the city and buys paraphernalia associated with witchcraft, including a book (‘How to Be a Witch: A Primer’). Returning home, she designs sigils and chooses an alternate name. Joan performs a conjuration spell and asks for Gregg to come to her. Shortly afterwards, she telephones Gregg, who agrees to come round to the Mitchell house. Joan and Gregg fuck. Joan decides to ask Gregg if he knows where Nikki is. Gregg tells Joan he doesn’t, and he begins to flirt with Joan, referring to her as ‘Mrs Robinson’ (in an overt reference to Charles Webb’s 1963 novel The Graduate). Joan visits the city and buys paraphernalia associated with witchcraft, including a book (‘How to Be a Witch: A Primer’). Returning home, she designs sigils and chooses an alternate name. Joan performs a conjuration spell and asks for Gregg to come to her. Shortly afterwards, she telephones Gregg, who agrees to come round to the Mitchell house. Joan and Gregg fuck.

Joan approaches Marion and asks to be initiated into the coven. Marion warns Joan not to ‘play with it [witchcraft]’. Meanwhile, Joan experiences repeated nightmares which involve a masked man (Bill Hinzman) breaking into her home and attempting to rape her… Somewhat ironically, Season of the Witch was produced in the same year that saw the broadcast of the final episodes of the long-running witchcraft-themed sitcom Bewitched (1964-72). Like Bewitched, Season of the Witch locates witchcraft within modern-day American suburbia. Joan is introduced to witchcraft via a casual conversation at nothing more exciting or unusual than a suburban party; a friend’s comments about the activities of a common acquaintance, Marian, piques her interest. Marian is regarded with scorn and derision by Joan’s group of friends; but regardless of this, and seeing in witchcraft a possible escape from her humdrum and repressed existence, Joan approaches Marian, who initiates Joan into the world of witchcraft by recommending a book about the subject. Witchcraft is here used as a metaphor for the Women’s Lib movement, Joan’s interest in the topic growing out of a rising awareness of the frustration and subjugation she experiences as ‘Jack’s wife’.  Like Romero’s later Martin (1978) – which ambiguously depicts the vampirism of its protagonist (John Amplas), never quite confirming whether or not he is delusional in his belief that he is a vampire – Season of the Witch juxtaposes the supernatural with the suburban and banal, offering a form of ‘daylight’ horror. Unarguably, the true ‘horror’ within the film is the climate of conformity, subjugation and manipulation that operates within the suburbs, repressing women like Joan; witchcraft, represented in the film as a commodified belief system (its tenets outlined in commercially-available books – ‘How to Be a Witch: A Primer’ – and the objects required for its rituals being sold in stores) offers a cathartic outlet for Joan and women like her, regardless of whether it (witchcraft) is ‘real’ or not. As with Martin, Romero refuses to steadfastly confirm or deny the suggestions of the supernatural within the story: the film is about Joan’s dissatisfaction with her suburban life which leads to her fascination with the occult. Like Martin, it is a picture about belief in the supernatural rather than the supernatural itself, with Joan’s interest in witchcraft acting subtly as a metaphor for the Women’s Lib movement. As Marco Maurizi has observed, ‘As Jack’s Wife and Martin show, Romero is interested in the supernatural not as a metaphysician, but as a sociologist’ (Maurizi, 2011: 126). Romero’s film is both culturally subversive, sticking a pin in the values of suburbia and foregrounding the patriarchal assumptions of American society, and equally subversive in its approach to the conventions of the horror genre. Like Romero’s later Martin (1978) – which ambiguously depicts the vampirism of its protagonist (John Amplas), never quite confirming whether or not he is delusional in his belief that he is a vampire – Season of the Witch juxtaposes the supernatural with the suburban and banal, offering a form of ‘daylight’ horror. Unarguably, the true ‘horror’ within the film is the climate of conformity, subjugation and manipulation that operates within the suburbs, repressing women like Joan; witchcraft, represented in the film as a commodified belief system (its tenets outlined in commercially-available books – ‘How to Be a Witch: A Primer’ – and the objects required for its rituals being sold in stores) offers a cathartic outlet for Joan and women like her, regardless of whether it (witchcraft) is ‘real’ or not. As with Martin, Romero refuses to steadfastly confirm or deny the suggestions of the supernatural within the story: the film is about Joan’s dissatisfaction with her suburban life which leads to her fascination with the occult. Like Martin, it is a picture about belief in the supernatural rather than the supernatural itself, with Joan’s interest in witchcraft acting subtly as a metaphor for the Women’s Lib movement. As Marco Maurizi has observed, ‘As Jack’s Wife and Martin show, Romero is interested in the supernatural not as a metaphysician, but as a sociologist’ (Maurizi, 2011: 126). Romero’s film is both culturally subversive, sticking a pin in the values of suburbia and foregrounding the patriarchal assumptions of American society, and equally subversive in its approach to the conventions of the horror genre.

However, because of its refusal to obey the paradigms of the horror film, Season of the Witch may be frustrating to viewers expecting a more conventional horror picture. As with There’s Always Vanilla, Season of the Witch is also very much a product of its time – particularly in its handling of the character of Raymond Laine’s Gregg, a trickster type who enters Joan’s life via her daughter Nikki and who embodies the archetype of pot-smoking youth of the late-1960s/early-1970s. However, the picture achieves a more universal relevance in its exploration of Joan’s cultural and personal repression, expressing this via a number of striking setpieces in which Joan’s suburban home takes on a menacing appearance at night as she experiences a recurring nightmare involving a masked intruder (played by Bill Hinzman) in her house. Romero constructs these dream sequences using canted angles, colour contrasts, shades, camera movement and montage to turn the domestic home into a space of nightmares. He employs tight closeups of the objects in Joan’s house and shots which include shadows cast across the walls by the branches of the trees outside; the effect is disorienting and subtly menacing, as if Joan’s home takes on labyrinthine qualities. Shots of an empty mirror become filled with the potential for terror; a kitsch statuette of a bull casts a sinister shadow upon the wall behind it. These fantasy sequences are, like those in Martin, presented in such a way as to make it as difficult for the viewer to distinguish between nightmare and reality as it is for Joan. At one point, Romero includes a short series of shots in which Joan recoils in horror as, via a point-of-view shot, we see what has caused this reaction: hands reach up from the other side of her bed, rather like the famous dream sequence in Bunuel’s Los Olvidados (1950) in which Pedro sees the hand of Jaibo emerge from beneath his bed to steal a chunk of rotting meat. In Los Olvidados, this moment symbolises Jaibo’s pernicious and persistent role in Pedro’s life, stealing from the youth in the manner of a parasite; in Season of the Witch, Joan’s horrified reaction is followed by the revelation that the hands belong to her husband Jack, but the connotations of the scene are similar to those of the comparable scene in the Bunuel picture – Jack is a persistent, parasitic and draining presence in the life of his wife Joan. However, because of its refusal to obey the paradigms of the horror film, Season of the Witch may be frustrating to viewers expecting a more conventional horror picture. As with There’s Always Vanilla, Season of the Witch is also very much a product of its time – particularly in its handling of the character of Raymond Laine’s Gregg, a trickster type who enters Joan’s life via her daughter Nikki and who embodies the archetype of pot-smoking youth of the late-1960s/early-1970s. However, the picture achieves a more universal relevance in its exploration of Joan’s cultural and personal repression, expressing this via a number of striking setpieces in which Joan’s suburban home takes on a menacing appearance at night as she experiences a recurring nightmare involving a masked intruder (played by Bill Hinzman) in her house. Romero constructs these dream sequences using canted angles, colour contrasts, shades, camera movement and montage to turn the domestic home into a space of nightmares. He employs tight closeups of the objects in Joan’s house and shots which include shadows cast across the walls by the branches of the trees outside; the effect is disorienting and subtly menacing, as if Joan’s home takes on labyrinthine qualities. Shots of an empty mirror become filled with the potential for terror; a kitsch statuette of a bull casts a sinister shadow upon the wall behind it. These fantasy sequences are, like those in Martin, presented in such a way as to make it as difficult for the viewer to distinguish between nightmare and reality as it is for Joan. At one point, Romero includes a short series of shots in which Joan recoils in horror as, via a point-of-view shot, we see what has caused this reaction: hands reach up from the other side of her bed, rather like the famous dream sequence in Bunuel’s Los Olvidados (1950) in which Pedro sees the hand of Jaibo emerge from beneath his bed to steal a chunk of rotting meat. In Los Olvidados, this moment symbolises Jaibo’s pernicious and persistent role in Pedro’s life, stealing from the youth in the manner of a parasite; in Season of the Witch, Joan’s horrified reaction is followed by the revelation that the hands belong to her husband Jack, but the connotations of the scene are similar to those of the comparable scene in the Bunuel picture – Jack is a persistent, parasitic and draining presence in the life of his wife Joan.

The merging of fantasy and reality is present from the film’s striking opening sequence onwards. The picture begins with what is eventually revealed to be a dream sequence. The opening titles play over shots of Joan and Jack walking through a wooded area, Joan following Jack by a number of paces; Jack paying no attention to his wife. This is accompanied on the soundtrack by eerie sounds of a church organ and heartbeat. In a repeated gesture, Jack pushes branches aside for himself and, after he has passed through the gaps they offer, lets them go. Romero cuts to close-ups of Joan’s face, the branches striking her and clawing at her skin, leaving bleeding wounds. As they walk through the woods, Joan notices a lone, unaccompanied baby crawling on the ground. This parodic nightmare of domesticity comes to a head when Jack puts Joan into a car with a dog lead around her neck. He takes her to a dog pound, where she is placed in a cage as if she were a stray animal. From here, Joan finds herself in a suburban home where a salesman shows her around, pointing out a TV set ‘designed to give you ideas, if you run out of ideas’ and a giggling group of housewives who are ‘available for bridge and tea mornings, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera’. Joan looks in a mirror and sees herself as an elderly woman before awakening from her nightmare. (The image of Joan as an older woman, with gray hair, which appears in the mirror recurs at several points in the film’s narrative. It’s an image that speaks of Joan’s dissociation and alienation.) It’s a bold and memorable opening sequence which symbolises Joan’s problems, representing her as ‘Jack’s Wife’ – the film’s original, and far more fitting, title. The merging of fantasy and reality is present from the film’s striking opening sequence onwards. The picture begins with what is eventually revealed to be a dream sequence. The opening titles play over shots of Joan and Jack walking through a wooded area, Joan following Jack by a number of paces; Jack paying no attention to his wife. This is accompanied on the soundtrack by eerie sounds of a church organ and heartbeat. In a repeated gesture, Jack pushes branches aside for himself and, after he has passed through the gaps they offer, lets them go. Romero cuts to close-ups of Joan’s face, the branches striking her and clawing at her skin, leaving bleeding wounds. As they walk through the woods, Joan notices a lone, unaccompanied baby crawling on the ground. This parodic nightmare of domesticity comes to a head when Jack puts Joan into a car with a dog lead around her neck. He takes her to a dog pound, where she is placed in a cage as if she were a stray animal. From here, Joan finds herself in a suburban home where a salesman shows her around, pointing out a TV set ‘designed to give you ideas, if you run out of ideas’ and a giggling group of housewives who are ‘available for bridge and tea mornings, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera’. Joan looks in a mirror and sees herself as an elderly woman before awakening from her nightmare. (The image of Joan as an older woman, with gray hair, which appears in the mirror recurs at several points in the film’s narrative. It’s an image that speaks of Joan’s dissociation and alienation.) It’s a bold and memorable opening sequence which symbolises Joan’s problems, representing her as ‘Jack’s Wife’ – the film’s original, and far more fitting, title.

Following this opening nightmare, Joan visits her psychiatrist, Dr Miller, and explains the dream to him. ‘Dreams, what are they?’, he queries, ‘Truth is something very difficult to live with. And because of this we spend a great deal of time covering it. But truth will out and we dream. The least qualified person to understand a dream is the dreamer’. This brief scene outlines the narrative significance Joan’s various dreams and nightmares have within the film – confusing and difficult to decode for her, and filled with symbolism that seems readily apparent to the film’s viewers, representing Joan’s stifling sense of entrapment within both her role as Jack’s wife and, more broadly, the norms of suburban life.  Joan’s retrenchment into witchcraft is subtly criticised by Romero, who in interviews suggests that Joan is to some extent complicit in the very aspects of her life which she finds repressive: ‘The fact is that every forward motion in the film is caused by that person [Joan] … yet she perceives the world as making everything happen to her. In fact, she can’t do any of it without being able to conjure up, pun intended, a reason for it happening that is not coming from within her. She needs to be able to say, “The Devil made me do it!” Which at once is the plight of womanhood, or any minority, and the genocide—it’s very hard to perceive yourself as the cause of something that might make it better’ (Romero, quoted in Williams, 2015: 53). This theme is explored in a sequence in which Joan, Nikki, Gregg and Joan’s friend Shirley retire to Joan’s home and Gregg demonstrates the power of autosuggestion, convincing Shirley that an ordinary cigarette contains marijuana; Shirley believes Gregg and, despite the cigarette containing nothing more potent than regular tobacco, her behaviour suggests she is ‘getting high’. A firm materialist, Gregg pooh-poohs any belief in metaphysics, referring to witchcraft as ‘Bullshit! People just refuse to admit they’re piles of dust, that’s all’, and suggesting that witchcraft ‘only works because people believe it works [….] Your mind does the rest. It’s all a mind trick’. Joan’s retrenchment into witchcraft is subtly criticised by Romero, who in interviews suggests that Joan is to some extent complicit in the very aspects of her life which she finds repressive: ‘The fact is that every forward motion in the film is caused by that person [Joan] … yet she perceives the world as making everything happen to her. In fact, she can’t do any of it without being able to conjure up, pun intended, a reason for it happening that is not coming from within her. She needs to be able to say, “The Devil made me do it!” Which at once is the plight of womanhood, or any minority, and the genocide—it’s very hard to perceive yourself as the cause of something that might make it better’ (Romero, quoted in Williams, 2015: 53). This theme is explored in a sequence in which Joan, Nikki, Gregg and Joan’s friend Shirley retire to Joan’s home and Gregg demonstrates the power of autosuggestion, convincing Shirley that an ordinary cigarette contains marijuana; Shirley believes Gregg and, despite the cigarette containing nothing more potent than regular tobacco, her behaviour suggests she is ‘getting high’. A firm materialist, Gregg pooh-poohs any belief in metaphysics, referring to witchcraft as ‘Bullshit! People just refuse to admit they’re piles of dust, that’s all’, and suggesting that witchcraft ‘only works because people believe it works [….] Your mind does the rest. It’s all a mind trick’.

In an interview given by Romero after the production of both Season of the Witch and The Crazies but before the release of either picture, the director reflected on the differing production circumstances of the two films: even though The Crazies was shot after Season of the Witch, it was to be released first ‘for several reasons. First of all, it was presold. We had the distributor before we produced the film, and in fact, it’s a coproduction with the distributor, Cambist Films […] Secondly, it was shot on 35mm and Jack’s Wife was shot in 16[mm]. Jack’s Wife has yet to be, once it’s sold, blown up, whereas The Crazies, once I get the cut, we can have a print in a few weeks’ (Romero, quoted in Nicotero, 1973: 32-3).

The Crazies (1973) The Crazies (1973)

Beginning with a sequence in which a father commits an act of family annihilation, slitting the throat of his wife before setting their home alight, The Crazies focuses on volunteer firefighter and former Green Beret David (Will McMillan) and his pregnant wife, nurse Judy (Lane Carroll). The borough in which they live, Pennsylvania’s Evans City, is soon placed in quarantine by the National Guard: a military-produced toxin, codenamed ‘Trixie’, designed for use in Vietnam, has been inadvertently unleashed upon the local population following a military plane crash in the area. Exposure to Trixie leaves a non-immune individual either dead or incurably insane, committing acts of horrendous violence. Fearing for the baby, Judy’s employer, Dr Brookmyre (Will Disney), advises Judy to flee the city as soldiers and officers arrive – among them Major Ryder (Harry Spillman) and Colonel Peckem (Lloyd Hollar) – clad in white Hazmat-style suits with gas masks to prevent exposure to Trixie. On the way out of Evans City, Judy encounters David and his friend Clank (Harold Wayne Jones). They team up but are stopped by a group of soldiers who corral them into a truck which also contains local man Artie Fulton (Richard Liberty) and his daughter Kathy (Lynn Lowry), along with a sick man named Winston (Norman Chase). The military draft in Dr Watts (Richard France), one of the scientists who created Trixie, asking him to work on an antidote. Meanwhile, David and Judy’s group become troubled by their proximity to the infection, finding it difficult to determine if those around them – and, for that matter, themselves – have been infected. Crank begins to display a propensity for violence that could be either a result of the pressures he’s been under or a symptom of infection by Trixie; Artie and his daughter Kathy also begin to show signs of an incestuous desire that underlies their relationship, and again it’s unclear whether this is a result of infection by Trixie or simply a manifestation of a pre-existing tensions.  When Judy begins to act strangely, David tries to protect her, leading the survivors into a head-on collision with the occupying soldiers. When Judy begins to act strangely, David tries to protect her, leading the survivors into a head-on collision with the occupying soldiers.

A stark depiction of a state of emergency, made during an era in which America had been wracked by anti-war protests and the riots and demonstrations during the battle for Civil Rights in the 1960s, The Crazies offers a bold examination of exactly how fine the line between ‘self’ and ‘other’ is (via its focus on the difficulty in distinguishing between those infected by Trixie and those who have not been touched by the toxin). The film has many parallels with Romero’s later Dawn of the Dead, similarities which are both thematic and aesthetic: for example, in the rhythms of the editing, which for much of the film approaches montage and uses many camera setups and rapid cuts. Tony Williams has compared Romero’s use of quick cuts and many static camera setups to comic books, arguing that Romero’s ‘recurrent use of movement within stationary camera angles and editing practises resembl[es] a comic book artist’s use of panels’ (Williams, 2015: 65). In a 1979 interview, Romero suggested that he ‘categorize[s] The Crazies and Dawn stylistically as being in the same family and Jack’s Wife and Martin similarly’ (Romero, quoted in Lippe et al, 1979: 61). The Crazies offers an allegorical reflection on many then-current issues, including the use of chemical weapons (such as Agent Orange) in the Vietnam War, and the handling of unrest at home. Reflecting on this aspect of the picture, Romero commented that ‘It [The Crazies] was made just around the time of Kent State [….] Ultimately, I think the film deals with the politics a little too lightly. It has sort of an outrageous, bawdy style, and some people may have thought we were making fun of politics, exploiting Vietnam and the Kent State tragedy. We weren’t at all. In fact, The Crazies was a very angry and radical film, if one sees through the comic surface’ (Romero, quoted in Seligson, 1981: 77).  Created by the military as a biological weapon, Trixie is an unknown quantity to the soldiers. When they draft in Dr Watts to help craft an antidote, he is understandably reluctant to travel to Evans City and suggests that in helping to make Trixie, he only worked on one specific aspect of the project and was not fully cognisant of the consequences of the project. Watts is chastised by Peckem, who declares angrily, ‘Look, it’s you “think boys” who created this thing in the first place’. For his part, Watts reminds Peckem that the effects of Trixie will be impossible to cover up: ‘It’s not going to run its course and be reduced to nothing’, Watts says, ‘How do you guys explain a town that’s either wiped out or reduced to mindlessness? [….] It leaves its victims either dead or incurably mad’. When Watts does indeed achieve a breakthrough and, working in the science lab of the local high school, produce an antidote, he rushes out to transport it in a vial to Colonel Peckem but is mistaken by the soldiers for a regular citizen. Watts protests that he is a scientist and is working with the military, but finds himself pushed along by other citizens of Evans City into a staircase, where he tumbles down the stairs; Romero punctuates this moment with a shot of the unconscious (or perhaps dead) Watts’ bloodstained forehead and a shot of the smashed vial. Again, the military’s poor communication and mismanagement of the situation results in the loss of what seems to be the only antidote to the toxin. Created by the military as a biological weapon, Trixie is an unknown quantity to the soldiers. When they draft in Dr Watts to help craft an antidote, he is understandably reluctant to travel to Evans City and suggests that in helping to make Trixie, he only worked on one specific aspect of the project and was not fully cognisant of the consequences of the project. Watts is chastised by Peckem, who declares angrily, ‘Look, it’s you “think boys” who created this thing in the first place’. For his part, Watts reminds Peckem that the effects of Trixie will be impossible to cover up: ‘It’s not going to run its course and be reduced to nothing’, Watts says, ‘How do you guys explain a town that’s either wiped out or reduced to mindlessness? [….] It leaves its victims either dead or incurably mad’. When Watts does indeed achieve a breakthrough and, working in the science lab of the local high school, produce an antidote, he rushes out to transport it in a vial to Colonel Peckem but is mistaken by the soldiers for a regular citizen. Watts protests that he is a scientist and is working with the military, but finds himself pushed along by other citizens of Evans City into a staircase, where he tumbles down the stairs; Romero punctuates this moment with a shot of the unconscious (or perhaps dead) Watts’ bloodstained forehead and a shot of the smashed vial. Again, the military’s poor communication and mismanagement of the situation results in the loss of what seems to be the only antidote to the toxin.

John Kenneth Muir has argued that the film’s images of soldiers invading private homes and disrupting high school dances ‘are provocative, and even inflammatory’ (Muir, 2011: 253). The film ‘pulls no punches’ in depicting the impact of martial law, soldiers raiding private residence ‘with no restrictions and no explanations’, shooting fleeing citizens in the back, ‘steal[ing] wallets, loot[ing] jewelry and similarly misbehav[ing] in the homes they occupy, revealing themselves to be little more than thugs and thieves. Romero’s point is, perhaps, that freedom in America is just one executive order away from destruction’ (ibid.). Soldiers are shown burning the bodies of Evans City’s citizens on large bonfires lit with flamethrowers; the soldiers riffle through the pockets of the corpses, looting their contents, whilst laughing and joking: the audience might wonder if these soldiers are ‘crazies’. Later, soldiers are shown committing what seem to be acts of almost indiscriminate killing, slaughtering a family and torching the corpses of a toddler’s parents in front of the child himself. Certainly, the soldiers are, in their association with violence, indistinguishable from the infected. In one scene, the soldiers are shown invading the home of an elderly couple, and Romero slyly cuts to a framed photograph of the husband, as a much younger man, dressed in an Air Force uniform, suggesting that the elderly man is – given his age – a veteran of the Second World War. Children playing wargames are interrupted by the soldiers too. No space, it seems, is safe. Even the local church is, despite the protestations of the priest, not immune from invasion by the National Guard, who storm into the building during a service in order to herd the churchgoers to the high school where the townsfolk are being kept. In response, the priest wanders into the street and performs an act of self-immolation, pouring petrol upon himself before setting himself alight in a moment which references Malcolm Browne’s famous photograph of the self-sacrifice of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức in 1963. In another sequence, the iron fist of the military results in unnecessary deaths when the Peckem orders a group of soldiers to seize all civilian weapons, including the guns of the policeforce; and when two soldiers tussle with a police officer, attempting to take his gun from him, this results in the gun misfiring and the police officer being killed. Muir also suggests that ‘it’s not hard’ to see the film’s depiction of an infectious ‘insanity’ as a metaphor for the spread of Communism (ibid.: 254). John Kenneth Muir has argued that the film’s images of soldiers invading private homes and disrupting high school dances ‘are provocative, and even inflammatory’ (Muir, 2011: 253). The film ‘pulls no punches’ in depicting the impact of martial law, soldiers raiding private residence ‘with no restrictions and no explanations’, shooting fleeing citizens in the back, ‘steal[ing] wallets, loot[ing] jewelry and similarly misbehav[ing] in the homes they occupy, revealing themselves to be little more than thugs and thieves. Romero’s point is, perhaps, that freedom in America is just one executive order away from destruction’ (ibid.). Soldiers are shown burning the bodies of Evans City’s citizens on large bonfires lit with flamethrowers; the soldiers riffle through the pockets of the corpses, looting their contents, whilst laughing and joking: the audience might wonder if these soldiers are ‘crazies’. Later, soldiers are shown committing what seem to be acts of almost indiscriminate killing, slaughtering a family and torching the corpses of a toddler’s parents in front of the child himself. Certainly, the soldiers are, in their association with violence, indistinguishable from the infected. In one scene, the soldiers are shown invading the home of an elderly couple, and Romero slyly cuts to a framed photograph of the husband, as a much younger man, dressed in an Air Force uniform, suggesting that the elderly man is – given his age – a veteran of the Second World War. Children playing wargames are interrupted by the soldiers too. No space, it seems, is safe. Even the local church is, despite the protestations of the priest, not immune from invasion by the National Guard, who storm into the building during a service in order to herd the churchgoers to the high school where the townsfolk are being kept. In response, the priest wanders into the street and performs an act of self-immolation, pouring petrol upon himself before setting himself alight in a moment which references Malcolm Browne’s famous photograph of the self-sacrifice of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức in 1963. In another sequence, the iron fist of the military results in unnecessary deaths when the Peckem orders a group of soldiers to seize all civilian weapons, including the guns of the policeforce; and when two soldiers tussle with a police officer, attempting to take his gun from him, this results in the gun misfiring and the police officer being killed. Muir also suggests that ‘it’s not hard’ to see the film’s depiction of an infectious ‘insanity’ as a metaphor for the spread of Communism (ibid.: 254).

Quite directly, Romero suggests that the heavy hand of the military force is responsible for exacerbating the violence of the situation. One of the characters in the picture observes that ‘You put martial law on a town, drive a perimeter around them like that and you’re just polarizing the situation. That army becomes an invasionary force. Those people are gonna resist’. Later, Major Ryder wonders how he ‘can hold a perimeter and fight a small-scale war at the same time […] Many of the people in the outlying areas are farmers. They’ve got weapons’ – and the infected and non-infected are largely indistinguishable, other than through their behaviour. When the soldiers, armed and dressed in their white protective suits and gasmasks, approach a farm and the farmer shoots back with his shotgun, the viewer is left wondering whether the farmer is simply infected or if he is reacting in a rational manner, protecting his home and family from a perceived threat. Quite directly, Romero suggests that the heavy hand of the military force is responsible for exacerbating the violence of the situation. One of the characters in the picture observes that ‘You put martial law on a town, drive a perimeter around them like that and you’re just polarizing the situation. That army becomes an invasionary force. Those people are gonna resist’. Later, Major Ryder wonders how he ‘can hold a perimeter and fight a small-scale war at the same time […] Many of the people in the outlying areas are farmers. They’ve got weapons’ – and the infected and non-infected are largely indistinguishable, other than through their behaviour. When the soldiers, armed and dressed in their white protective suits and gasmasks, approach a farm and the farmer shoots back with his shotgun, the viewer is left wondering whether the farmer is simply infected or if he is reacting in a rational manner, protecting his home and family from a perceived threat.

Certainly, the film offers many open parallels with the then-ongoing war in Vietnam. In his book about Romero, Tony Williams has pointed out some of the specific visual references within the film to examples of photojournalism that came out of the Vietnam War, including what he suggests is a direct allusion to Eddie Adams’ famous photograph of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner in Saigon, the photograph which won Adams both a World Press Photo award and 1969 Pullizer Prize for Spot News Photography (Williams, 2015: 67-8). On a more general level, however, when David and his fellow escapees flee from the military force that has invaded Evansville, they are pursued through the countryside and vastly outnumbered (and out-resourced) but manage to turn the tables, David using a carbine rifle to shoot down a military helicopter, a moment which Tony Williams suggests parallels ‘the Viet Cong’s frequent defeats of technologically-advanced enemies’ (ibid.: 68). In depicting a Vietnam veteran who is pursued across the countryside, the film also has some echoes of David Morrell’s then-recently published novel First Blood (1972) and the pursuit of Vietnam vet Rambo (given the first name John in George P Costmatos’ 1982 film adaptation) by National Guardsmen across the wilds of Kentucky.  Throughout the film, Romero subtly draws the audience’s attention towards water taps and people drinking from them; there’s some irony in this, as with the progression of the narrative the audience becomes cognisant that Trixie is being spread through the water supply, though this is something about which the characters in the film aren’t aware until much later in the picture. In fact, the film opens with a moment of foreshadowing in which a young girl steals into the family bathroom in the dead of night to obtain a drink of water, only to be interrupted by her brother who scares her. Their game is interrupted by a very real threat, however. The children hear sounds of objects being smashed downstairs; in response to this, the children hide. ‘Billy, this is all wet here’, the girl tells her brother in reference to the floor on which they stand. ‘Smells like kerosene’, Billy responds. Billy and his sister discover that their home is being torn apart by their father, and the young girl goes looking for her mother, only to find her in bed with her throat slit. The father sets the house alight. Throughout the film, Romero subtly draws the audience’s attention towards water taps and people drinking from them; there’s some irony in this, as with the progression of the narrative the audience becomes cognisant that Trixie is being spread through the water supply, though this is something about which the characters in the film aren’t aware until much later in the picture. In fact, the film opens with a moment of foreshadowing in which a young girl steals into the family bathroom in the dead of night to obtain a drink of water, only to be interrupted by her brother who scares her. Their game is interrupted by a very real threat, however. The children hear sounds of objects being smashed downstairs; in response to this, the children hide. ‘Billy, this is all wet here’, the girl tells her brother in reference to the floor on which they stand. ‘Smells like kerosene’, Billy responds. Billy and his sister discover that their home is being torn apart by their father, and the young girl goes looking for her mother, only to find her in bed with her throat slit. The father sets the house alight.

With this opening sequence, Romero deftly sketches the world depicted in The Crazies, foreshadowing the revelation that Trixie has been spread through the water supply and also foregrounding the film’s major theme of family being torn apart or disturbed by the infection. From here, the film presents the film’s opening titles, accompanied by a militaristic drumbeat on the soundtrack, before presenting the audience with another family: David and his wife Judy, who is pregnant with the couple’s first child. (Shortly afterwards, Romero confirms for the audience the death of the little girl, though Billy has survived but remains unresponsive and contaminated by Trixie.) Throughout the film, various scenes depict families in which a member runs – unexpectedly – amok: for example, as the infection takes hold Kathy’s overprotective father begins to molest his daughter sexually. These scenes, along with scenes depicting the military force attempting to cleanse the area of infection, bear strong echoes of Romero’s depiction of the family in Night of the Living Dead – most obviously, the sequence in which young Karen Cooper (Kyra Schon) murders her mother Helen (Marilyn Eastman) with a trowel. Where the staging of that specific scene in Night of the Living Dead paid homage to the shower scene from Hitchcock’s Pyscho (1960), in The Crazies Romero includes another allusion to Hitchcock’s shower scene when a soldier ascends the staircase of a family home to find in an upstairs bedroom nothing more sinister than an elderly lady who is knitting. However, the elderly woman charges at the soldier and plunges her knitting needle into him. Again, violence is swift and unexpected, its perpetrators behaving in surprising and unpredictable ways. (This is a very Hitchcockian theme too.) With this opening sequence, Romero deftly sketches the world depicted in The Crazies, foreshadowing the revelation that Trixie has been spread through the water supply and also foregrounding the film’s major theme of family being torn apart or disturbed by the infection. From here, the film presents the film’s opening titles, accompanied by a militaristic drumbeat on the soundtrack, before presenting the audience with another family: David and his wife Judy, who is pregnant with the couple’s first child. (Shortly afterwards, Romero confirms for the audience the death of the little girl, though Billy has survived but remains unresponsive and contaminated by Trixie.) Throughout the film, various scenes depict families in which a member runs – unexpectedly – amok: for example, as the infection takes hold Kathy’s overprotective father begins to molest his daughter sexually. These scenes, along with scenes depicting the military force attempting to cleanse the area of infection, bear strong echoes of Romero’s depiction of the family in Night of the Living Dead – most obviously, the sequence in which young Karen Cooper (Kyra Schon) murders her mother Helen (Marilyn Eastman) with a trowel. Where the staging of that specific scene in Night of the Living Dead paid homage to the shower scene from Hitchcock’s Pyscho (1960), in The Crazies Romero includes another allusion to Hitchcock’s shower scene when a soldier ascends the staircase of a family home to find in an upstairs bedroom nothing more sinister than an elderly lady who is knitting. However, the elderly woman charges at the soldier and plunges her knitting needle into him. Again, violence is swift and unexpected, its perpetrators behaving in surprising and unpredictable ways. (This is a very Hitchcockian theme too.)

The early sequences, in which Dr Brookmyre tells Judy to flee Evans City (‘I just don’t want you around here [….] Find David and the two of you stay away from people’) suggest that David and Judy will, at the climax of the picture, escape into a new world, Judy’s pregnancy offering hope that is juxtaposed with the despair of their immediate surroundings. However, Romero is too cynical a filmmaker to follow this paradigm and cuts their flight short in a cruel way. Comparisons may, of course, be drawn with Fran’s (Gaylen Ross) pregnancy to David (David Emge) in Dawn of the Dead, though that picture climaxes with David’s transformation into a flesh-eating ghoul and Fran’s helicopter flight to an uncertain future.

Video

There’s Always Vanilla There’s Always Vanilla

Pitched as a new 2k restoration based on ‘original film elements’, Arrow’s HD presentation of There’s Always Vanilla takes up 25Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc on which it is housed. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The film is uncut and runs for 92:29 mins. The film was shot on 16mm and looks fairly good on this Blu-ray. There’s a level of detail that is above what one would expect from the DVD format, but there’s a softness to the image in some places. Damage is limited to vertical lines, which are notoriously difficult to remove. Contrast is very bold in places, resulting in a ‘thin’ appearance to the footage: skin tones are sometimes bleached out and flat-looking. Colours are also a little ‘off’ in places, with a magenta push in a number of scenes which looks quite unhealthy and unnatural. A solid encode to disc retains the structure of 16mm film. For a picture which is often cited as being ‘lost’, this presentation is pleasing, but there are clear limitations inherent in the source materials used for this presentation – whatever they may be.  Season of the Witch Season of the Witch

Romero shot the film under the title of Jack’s Wife; this title foregrounds the extent to which Joan sees herself as an extension or possession of her husband. Upon completion, Romero struggled to find distribution for the picture, his original edit of the film being 130 minutes in length. Bought by Jack Harris for distribution, the picture was cut to 89 minutes and released under the more salacious title Hungry Wives!, both the title and promotional material marketing it as a softcore sex film. This edit of the film was released on VHS by Astra in the UK, pre-VRA, as Season of the Witch, the title that Harris attached to the picture when he rereleased it following the success of Dawn of the Dead. Though Romero’s original 130 minute edit of the picture is considered ‘lost’, an alternate cut of intermediate length (c.105 mins) appeared on VHS during the 1990s and was released on videocassette in the UK by Redemption. This version appeared on DVD in America from Anchor Bay in 2005, though the scene in which Joan shops for witchcraft paraphernalia accompanied on the soundtrack by Donovan’s ‘Season of the Witch’ featured an alternate, ‘cleaner’ version of the Donovan track. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of the film includes both the 89:40 minute edit (titled Season of the Witch) and the 104:20 minute version (titled Jack’s Wife). The latter is a composite that uses the HD presentation of the shorter cut as its base, with the added footage being of a much lower quality (seemingly from a tape source). Season of the Witch takes up 24Gb of space on the disc, whereas the longer Jack’s Wife takes up 12Gb of space.  The extended cut adds the following material: The extended cut adds the following material:

- The scene in which Joan is shown waking up after the nightmare depicted in the opening sequence is extended; - Joan visiting the supermarket, dry cleaners and carwash before being shown in conversation with Nikki at the dinner table. Nikki asks Joan about her (Nikki’s) brother, who passed away, enquiring whether her brother died before or after Nikki was born. Jack enters and chastises Joan for leaving the garage door open. This scene leads into an extension of the house party scene in which Joan listens to her friends talking about Marion’s association with the coven; - An extension of the scene in which Joan and Shirley visit Marion. Marion performs a reading with the Tarot; - An extension of Marion’s monologue about witchcraft and Joan’s drive home; - An extension of Joan’s first meeting with Gregg; - An extension of the scene in which Gregg offers what he claims is a marijuana cigarette to Shirley; - An extension of the scene in which Gregg apologises to Joan for his humiliation of Shirley; - Jack talks with the police and tries to determine where Nikki has fled to; - Joan’s morning routine after her nightmare about the intruder; - Joan wandering through her house after performing the conjuration spell. The second addition is the most significant, in terms of the film’s narrative, with its revelation that Joan lost a child, and that the details about this event are hazy for Nikki.  Shot on 16mm and blown up to 35mm for theatrical exhibition, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. (Anchor Bay’s 2005 DVD clumsily cropped the compositions to 1.78:1.). The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The main feature is sourced from a new 4k restoration taken from the original camera negative. (As noted above, this forms the core of the extended version, to which lower quality inserts have been added.) The extended version is a much better picture, and it’s a shame that this version of the film is relegated to ‘second place’ and smaller file size – but given the fact that it’s a patchwork quilt of the 4k restoration and lower grade material, this is understandable. The film’s original photography makes much use of both a standard focal length to pull focus on specific objects and wide-angle lenses which add a sense of distortion to the nightmare sequences. This HD presentation contains very pleasing level of fine detail, which is evident throughout the film and particularly noticeable in closeups of objects and faces. Contrast levels are excellent, midtones exhibiting a very rich level of definition and blacks being deep. Little to no damage is present. Colours are naturalistic, the palette dominated by crisp autumnal colours during the opening sequence (which reminds me somewhat of William Eggleston’s famous portrait of his uncle, Adyn Schuyler Senior, with his assistant, Jasper Staples) and by kitsch pastels for many of the scenes depicting the interior of Joan’s house. On the shorter theatrical cut, a solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 16mm film. Shot on 16mm and blown up to 35mm for theatrical exhibition, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. (Anchor Bay’s 2005 DVD clumsily cropped the compositions to 1.78:1.). The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The main feature is sourced from a new 4k restoration taken from the original camera negative. (As noted above, this forms the core of the extended version, to which lower quality inserts have been added.) The extended version is a much better picture, and it’s a shame that this version of the film is relegated to ‘second place’ and smaller file size – but given the fact that it’s a patchwork quilt of the 4k restoration and lower grade material, this is understandable. The film’s original photography makes much use of both a standard focal length to pull focus on specific objects and wide-angle lenses which add a sense of distortion to the nightmare sequences. This HD presentation contains very pleasing level of fine detail, which is evident throughout the film and particularly noticeable in closeups of objects and faces. Contrast levels are excellent, midtones exhibiting a very rich level of definition and blacks being deep. Little to no damage is present. Colours are naturalistic, the palette dominated by crisp autumnal colours during the opening sequence (which reminds me somewhat of William Eggleston’s famous portrait of his uncle, Adyn Schuyler Senior, with his assistant, Jasper Staples) and by kitsch pastels for many of the scenes depicting the interior of Joan’s house. On the shorter theatrical cut, a solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 16mm film.

The Crazies The Crazies

The Crazies takes up 28Gb on its Blu-ray disc, and again the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Unlike the previous two pictures, The Crazies was shot on 35mm and is here presented in the 1.66:1 screen ratio, which would seem to be commensurate with the filmmakers’ intentions. The film is uncut, with a running time of 103:02 min. The presentation is based on a new 4k restoration from the film’s negative, and it’s an extremely pleasing presentation indeed. (There are one or two instances of stock footage of a lesser quality, which just serve to underscore how good the main presentation is.) It’s ‘clean’, with little to no damage present. The film’s original photography tends to favour standard focal lengths, making the interiors seems cramped and confined, with a recurring use of doorframes as secondary frames within the compositions, and the positioning of objects in the foreground to give a sense of depth even in shots filmed in low light and with a large aperture. Contrast in this presentation is excellent, with rich, deep blacks complemented by defined midtones and nicely-balanced highlights. Colours are natural and not over- or under-saturated. A crisp level of detail is present throughout, fine detail in closeups being very pleasing. Finally, a solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

All three pictures feature English LPCM 1.0 audio tracks and optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. In the case of all three films, the audio tracks are pleasing. The Crazies features some ultra-shrill high frequencies, but these seem to be a product of the limitations of the production rather than an issue with the audio track on this disc. Subtitles for all three films are accurate and easy to read. The extended cut of Season of the Witch features a lossy Dolby Digital mono track only, and this version of the film is also subtitle-less, unfortunately.

Extras

DISC ONE:  There’s Always Vanilla (92:29) There’s Always Vanilla (92:29)

- Audio commentary with Travis Crawford. Crawford reflects on the history and production of There’s Always Vanilla and discusses the picture’s absence on home video formats. - ‘Affair of the Heart: The Making of There’s Always Vanilla’ (29:43). This new documentary features input from John Russo and Russell Streiner, who produced There’s Always Vanilla, actors Judith Streiner (Ridley) and Richard Ricci, and the film’s sound recordist (Gary Streiner). The documentary offers strong engagement with the picture’s relationship with both its cultural and institutional contexts, and the participants discuss how the picture evolved from a 30 minute short. - ‘Digging Up the Dead: The Lost Films of George A Romero’ (15:56). In an archival interview recorded for inclusion on the Anchor Bay DVD release of Season of the Witch, Romero talks about There’s Always Vanilla and Season of the Witch. - Galleries: Filming Locations (11:30); Collectible Scans (1:09). The former features commentary from Romero ‘super fan’ Lawrence DeVincentz, identifying the locations used in the picture. - Trailer (1:45)  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

Season of the Witch - Theatrical version (as Hungry Wives!) (89:40) - Extended version (with SD inserts; as Jack’s Wife) (104:20) - Audio commentary with Travis Crawford. Crawford provides a commentary over the shorter edit of the picture. Crawford suggests the film is ‘the most underrated film in his [Romero’s] body of work’ and compares it with the films of John Cassavetes and Ingmar Bergman. - ‘When Romero Met Del Toro’ (55:40). Recorded in 2016, Romero speaks with Guilermo del Toro, and the pair discuss some of Romero’s films and their impact on the horror genre. - ‘The Secret Life of Jack’s Wife’ (17:17). In an archival interview, Jan White reflects on her role in Season of the Witch and talks about its lasting impact on her career. - Alternate Opening Titles: Jack’s Wife (3:33); Hungry Wives (3:36); Season of the Witch (3:27). - Location Gallery: Filming Locations (1:34); Collectible Scans (2:32). The first gallery includes commentary from DeVincentz, once again. - Trailers: Hungry Wives (1:31); Season of the Witch (1:47).  DISC THREE: DISC THREE:

The Crazies (103:02) - Audio commentary with Travis Crawford. Crawford provides yet another commentary track, and he’s joined by Bill Ackerman, who hosts the podcast Supporting Characters. They discuss the film’s relationship with Romero’s other pictures and talk about the ways in which the picture channels the anxieties of the period in which it was produced. - ‘Romero Was Here: Locating The Crazies’ (12:24). Lawrence DeVincentz tours some of the locations used in The Crazies. - ‘Crazy for Lynn Lowry’ (15:54). Lynn Lowry discusses her career and talks about her work in The Crazies. - Q&A with Lynn Lowry (35:52). This Q&A was recorded at the Abertoir Film Festival in Aberystwyth in 2016, and it sees Lowry reflecting on her work in horror pictures. - Audio interview with producer Lee Hessel (4:32). Hessel, the film’s producer, is interviewed by his son and discusses his role in the making of The Crazies. - Behind-the-scenes Footage (6:26). 8mm footage taken during the production by Sam Nicotero is presented with optional audio commentary by Lawrence DeVincentz. - Alternate Opening Titles (0:35). These bear the film’s alternate title, ‘Codename Trixie’. - Galleries: Filming Locations (26:56); Collectible Scans (6:04). Again, the former is accompanied by commentary from ‘uber fan’ DeVincentz. - Trailers and TV Spots: Trailer 1 (2:57); Trailer 2 (3:04); TV Spot 1 (1:04); TV Spot 2 (0:33).

Overall

In interviews, Romero frequently cited There’s Always Vanilla as his worst picture, and it’s hard not to agree with that statement: the film apes a number of other much more memorable films and does so in a less engaging manner than, say, Alfie. It’s a confused film, unsure of which direction it needs to take, and with jarring shifts in tone and approach. In interviews, Romero frequently cited There’s Always Vanilla as his worst picture, and it’s hard not to agree with that statement: the film apes a number of other much more memorable films and does so in a less engaging manner than, say, Alfie. It’s a confused film, unsure of which direction it needs to take, and with jarring shifts in tone and approach.

Season of the Witch is much better, however, with Romero returning to the horror genre loosely and with a strong sense of irony, in terms of his application of the paradigms of the genre, that would be carried through his later films – in particular, Martin, but also in Dawn of the Dead. It’s an impressive, clever and sensitive film; but the longer cut is a much more satisfying picture than the abbreviated Hungry Wives edit – and therefore, it’s a shame that this longer edit isn’t the default presentation on Arrow’s release and is subjected to much more severe compression than the theatrical edit (and is presented with a lossy audio track and no subtitles, to boot). Given the limitations of the source material and the tape-sourced inserts used to assemble the extended cut, this is understandable, but it’s frustrating nonetheless. The Crazies is also an excellent picture, even though in many ways it seems like a dry run for Dawn of the Dead, many of its themes, ideas and imagery finding its way into the sequel to Night of the Living Dead. (There are also some memorably grizzly special effects shots – notably a couple of bullet hits to various characters’ heads.) It’s a sharp and incisive look at American society during the early 1970s, and is also dramatically satisfying – and suitably bleak. All three films get pleasing presentations in this Blu-ray boxed set from Arrow Video. The presentation of There’s Always Vanilla is by far the weakest, owing to limitations with the source material, but the presentation of The Crazies is excellent. The films are complemented by a very strong array of contextual material too. For a fan of Romero’s work, this boxed set is an essential release, and is arguably one of the best releases of the year. References: Lippe, Richard et al, 1979: ‘The George Romero Interview’. In: Williams, Tony (ed), 2011: George A Romero: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 59-68 Maurizi, Marco, 2011: I Was a Teenage Critical Theorist: Zappa, Nagal, Romero. Lulu.com Muir, John Kenneth, 2011: Horror Films of the 1980s. London: McFarland & Company Nicotero, Sam, 1973: ‘Romero: An Interview with the Director of Night of the Living Dead’. In: Williams, Tony (ed), 2011: George A Romero: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 18-35 Seligson, Tom, 1981: ‘George Romero: Revealing the Monsters Within Us’. In: Williams, Tony (ed), 2011: George A Romero: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 74-87 Williams, Tony, 2015: The Cinema of George A Romero: Knight of the Living Dead. Columbia University Press Yakir, Dan, 1977: ‘Morning Becomes Romero’. In: Williams, Tony (ed), 2011: George A Romero: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 47-58 Please click on the images for full-sized screengrabs. There’s Always Vanilla

Season of the Witch

The Crazies

|

|||||

|