|

|

Secret Beyond the Door (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th November 2017). |

|

The Film

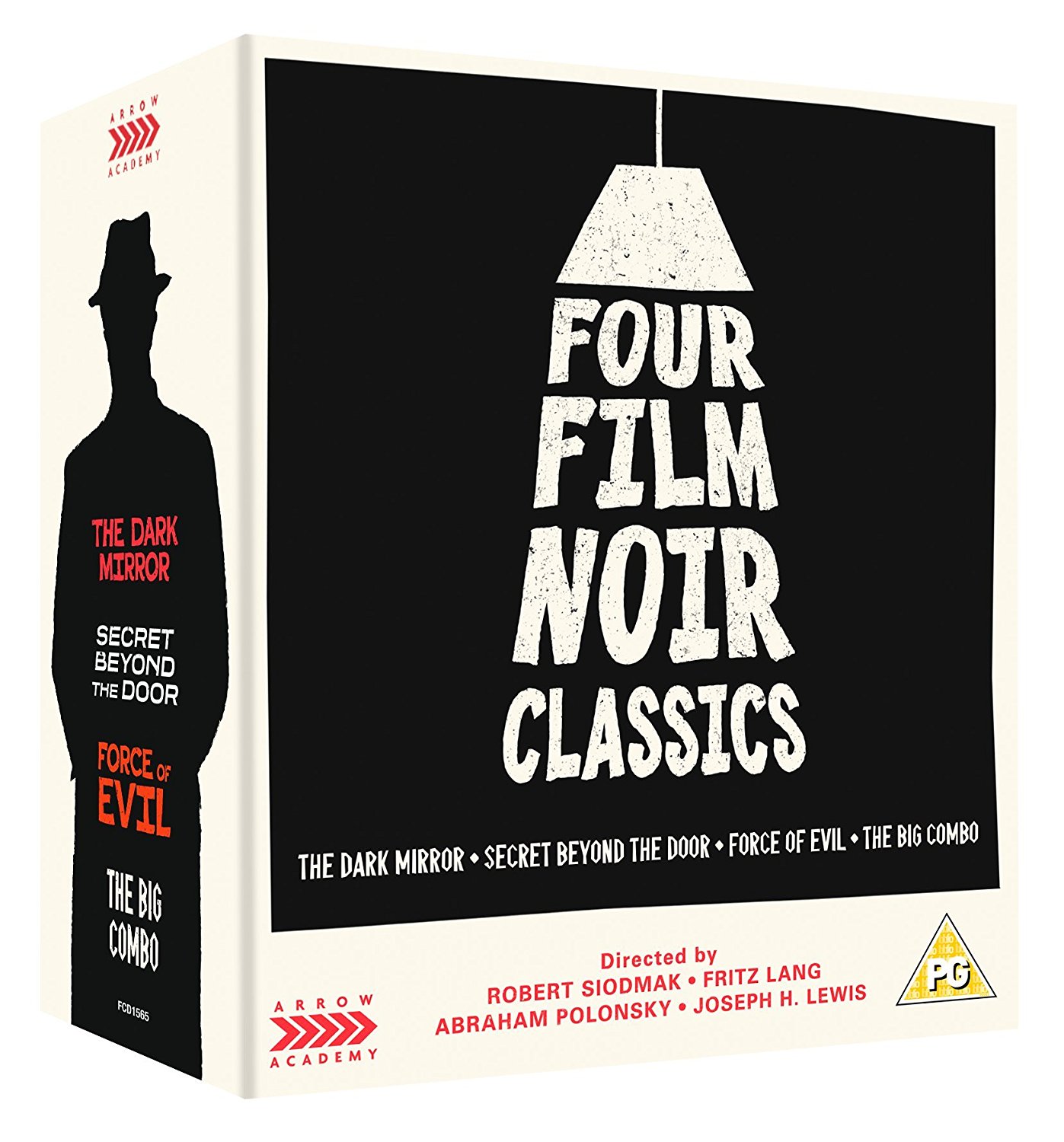

Four Film Noir Classics  The Dark Mirror (Robert Siodmak, 1946) The Dark Mirror (Robert Siodmak, 1946)

When Dr Frank Peralta is murdered, Detective Lieutenant Stevenson (Thomas Mitchell) discovers that the finger of suspicion is pointed towards Frank’s lover Ruth Collins (Olivia de Havilland), a newspaper stand girl. Upon meeting Ruth, Stevenson is surprised to find that the young woman’s character – sweet and meek – is opposite to what was suggested by Peralta’s neighbours. Ruth also seems to have plenty of witnesses, including a police office, to suggest she was elsewhere at the time of the murder, taking a walk through the park. Stevenson visits Ruth at her home and is shocked to discover that she has a twin sister, Terry (also played by de Havilland). Stevenson has both Ruth and Terry arrested, but the twin sisters provide alibis for one another, making it impossible for the District Attorney to prosecute either of them. Frustrated, Stevenson speaks with a psychiatrist, Dr Elliott (Lew Ayres), who knew Peralta and also knows Ruth. Elliott’s work focuses on twins, so he seems the perfect candidate to assist Stevenson in his investigation. Under the pretext of conducting a study about twins, Elliott approaches Terry and Ruth and asks them to allow him to study them in his laboratory at the university. They agree, somewhat reluctantly. Over a period of time which is unclear, Elliott conducts a series of tests with them, including a Rorschach ink blot test which he claims to Stevenson proves ‘one of our young ladies is insane. Very clever, very intelligent, but insane’. Knowing that both of the twins are attracted to him, and believing the motive for the killing of Peralta to be jealousy, Elliott sets a honey trap for the murderer with the intention of drawing the homicidal twin out into the open. During the 1940s, Robert Siodmak directed a number of iconic films noir for Universal, including The Killers in 1946, Cry of the City in 1948, Criss Cross in 1949 and The File on Thelma Jordan in 1950. Falling towards the start of Sidomak’s career as a director of films noir, The Dark Mirror falls into a narrow subtype of films noir which feature doppelgangers/doubles, sitting alongside Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation (released a year earlier in 1946) and the poverty row quickie The Guilty (John Reinhardt, released in the same year as The Dark Mirror, 1947). In The Dark Mirror, de Havilland essays two characters who embody the twin representations of women associated with classic films noir, which in Freudian terms equates to the distinction between the virtuous Madonna and the impure/corrupting Whore: in Siodmak’s picture, de Havilland plays both the sweet, innocent young woman (Ruth); and the seductive, murderous femme fatale (Terry). Ruth is innocent, pure and kind; Terry is seductive, manipulative and deadly. (De Havilland’s performance is on par with Jeremy Irons’ dual role as twin gynaecologists Elliot and Beverly Mantle in David Cronenberg’s 1988 picture Dead Ringers.) The dualistic identities of these two young women are represented visually, both via some fairly seamless trick photography which allows de Havilland to play both sisters on screen at the same time (a couple of optical effects shots stand out owing to their lesser quality on this Blu-ray presentation) and through some more esoteric symbolism: for example, the twin-like symmetry of the Rorschach ink blots that Dr Elliott uses to test the sisters.  Lew Ayres’ Dr Elliott is one in a long line of psychiatrists that feature in classic films noir, alongside Lee J Cobb’s police psychiatrist in The Dark Past (Rudolph Mate, 1948) and Sydney Greenstreet’s similar character in Conflict (Curtis Bernhardt, 1945). Given the themes of many films noir (the castrating femme fatale; obsessive sexuality; sadistic, and sometimes masochistic, relationships and violence), it is perhaps predictable that this style (or ‘genre’, if one wishes to consider film noir in such rigidly defined terms) became during the mid-1940s so obsessed with psychoanalytic theory, and some Freudian tenets are expounded explicitly in The Dark Mirror (and also in Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door, also included in this collection from Arrow). Lew Ayres’ Dr Elliott is one in a long line of psychiatrists that feature in classic films noir, alongside Lee J Cobb’s police psychiatrist in The Dark Past (Rudolph Mate, 1948) and Sydney Greenstreet’s similar character in Conflict (Curtis Bernhardt, 1945). Given the themes of many films noir (the castrating femme fatale; obsessive sexuality; sadistic, and sometimes masochistic, relationships and violence), it is perhaps predictable that this style (or ‘genre’, if one wishes to consider film noir in such rigidly defined terms) became during the mid-1940s so obsessed with psychoanalytic theory, and some Freudian tenets are expounded explicitly in The Dark Mirror (and also in Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door, also included in this collection from Arrow).

The film’s twin investigators, Detective Lieutenant Stevenson and Dr Elliott, complement one another: Stevenson dominates the first half of the picture, investigating the cold, hard facts of the case, whereas Elliott takes a dominant role in the second half of the film, examining the inner workings of the Collins sisters’ minds in order to identify which one of them is the killer. Stevenson’s investigation encompasses the physical evidence in the murder of Peralta, with Terry feigning surprise at Stevenson’s questions about her love life. ‘Guy generally fall in love with you, don’t they?’, Stevenson asks Terry, believing her to be Ruth. ‘For a policeman, you certainly spend a lot of time thinking about love’, Terry responds sharply. ‘Yeah, I’m a romantic type’, Stevenson quips back at her. A forensic investigation of the knife used in the murder reveals no evidence. The killer must have been wearing gloves, the scientist tells Stevenson. ‘There ought to be a state law against the sale of gloves to murderers’, Stevenson jokes. ‘You know what they’d do in the old days’, the scientist asserts. ‘That’s no good’, Stevenson responds, ‘Ladies bruise too easily’.  Elliott’s investigation, on the other hand, focuses on the interior of the human mind. As Elliott tells Stevenson when Stevenson asks him to help him, the best clues in such crimes come through ‘character, personality. Not even nature can duplicate personality, even in twins’. By studying the character and personality of the Collins twins, Elliott reasons that he will be able to identify which of them killed Peralta. He performs a series of tests – the ink blot test, a word association test – and disarms Stevenson with the confidence with which he claims he can tell the identical twin sisters apart, a skill which enables him to use their attraction to him to set a trap for the murderer. Elliott’s investigation, on the other hand, focuses on the interior of the human mind. As Elliott tells Stevenson when Stevenson asks him to help him, the best clues in such crimes come through ‘character, personality. Not even nature can duplicate personality, even in twins’. By studying the character and personality of the Collins twins, Elliott reasons that he will be able to identify which of them killed Peralta. He performs a series of tests – the ink blot test, a word association test – and disarms Stevenson with the confidence with which he claims he can tell the identical twin sisters apart, a skill which enables him to use their attraction to him to set a trap for the murderer.

Like Brian De Palma’s later Sisters (1974), which echoes The Dark Mirror in a number of ways, Siodmak’s picture offers a form of psychosexual terror that grows out of the suggestion that Ruth/Terry’s lovers can’t tell the twin sisters apart – and one of them is a murder, riddled with jealousy over the sexual attention given to her sister. This is to some extent terror assuaged by the assurance with which Dr Elliott is able to tell the two twin sisters apart. As Elliott sets his honey trap for the murderous twin, the killer attempts to ‘gaslight’ her sister by disturbing her sleep with lights and sounds – leading the innocent twin to begin to question her sanity. Like many of the films noir which feature a heavy emphasis on psychiatry, however, the film ends with a pat attempt to explain the motivations of the killer. (This is a trend which Hitchcock satirised brutally with the outrageous explanation given by Simon Oakland’s psychiatrist at the end of Psycho, 1960, which itself influenced a similar use of incredibly convulated explanations of a killer’s behaviour in any number of gialli all’italiana/Italian-style thrillers – notably Dario Argento’s 1970 L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo/The Bird with the Crystal Plumage.) ‘All women are rivals fundamentally’, Elliott offers at the end of The Dark Mirror, ‘but it never bothers them because they discount the successes of others and alibi their own failures in the grounds of circumstances. The circumstances are usually about the same, so they have fewer excuses to comfort themselves. That’s why sisters can hate each other with such intensity’.

Secret Beyond the Door (Fritz Lang, 1947) Secret Beyond the Door (Fritz Lang, 1947)

Celia Barrett (Joan Bennett), guilty of breaking off one engagement after another, dotes on her older brother Rick (Paul Cavanagh). Rick introduces Celia to his lawyer friend Bob Dwight (James Seay). When Rick dies, leaving everything to Celia, Bob takes care of her trust fund and warns her about ‘fortune-hunting husband[s]’. Smitten with Celia, Bob proposes to her, allowing her time to think about whether or not to accept his proposal whilst she takes a holiday in Mexico with her friend Edith (Natalie Schafer). In Mexico, Celia witnesses a knife fight: two men stand off against one another over the attentions of a young woman. Much to her own surprise, Celia finds herself excited – rather than horrified – by this display of violence which is tied to sexual jealousy. During the moment, Celia catches the eye of a man, who introduces himself as Mark Lamphere (Michael Redgrave). Mark is an architect and publisher of a magazine. Celia and Mark marry, Celia moving in to Mark’s large family home in Levender Falls. Mark’s home is filled with rooms that he has dressed in the same way as various famous rooms in which murders were committed; Mark believes firmly that certain rooms can dictate the behaviour of the people who live in them, even inspiring them to commit murder. Celia meets Mark’s sister Caroline (Anne Revere) and secretary Miss Robey (Barbara O’Neil), who suffered a facial disfigurement in her youth when she saved a young Mark from a fire. Celia is also shocked and horrified to discover that Mark has a son, David (Mark Dennis). David is the product of Mark’s previous marriage to a woman named Eleanor. Eleanor, Celia is told, died, and Mark treats David cruelly; then, one day, David tells Celia that Mark murdered Eleanor.  A tale of a homme fatale based on a story sourced from a women’s magazine, Secret Beyond the Door is told in an interestingly non-linear manner and given a breathy, spontaneous narration by Celia. The film begins with Celia’s wedding before cutting back to her relationship with her brother, the evolution of her affair with Bob and her initial encounter with Mark in Mexico – then revealing that the wedding we glimpsed in the film’s opening sequence was to Mark and not Bob. Celia’s narration has a stream-of-consciousness quality to it, inviting some comparisons with the narrational strategies of modernist novels such as, for example, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) or James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). ‘I remember, long ago, I read a book that told the meaning of dreams’, Celia begins as the film opens, ‘This is no time to think of danger. This is my wedding day’. As, onscreen, Celia steps from the shadows in her wedding dress, offscreen she narrates: ‘My heart is pounding so. The sound of it drowns out everything. It’s said that when you drown your whole life passes before you like a fast movie’, and with this – before we see the groom – the picture cuts abruptly to the past, with Celia being chastised by her brother for breaking off yet another engagement. A tale of a homme fatale based on a story sourced from a women’s magazine, Secret Beyond the Door is told in an interestingly non-linear manner and given a breathy, spontaneous narration by Celia. The film begins with Celia’s wedding before cutting back to her relationship with her brother, the evolution of her affair with Bob and her initial encounter with Mark in Mexico – then revealing that the wedding we glimpsed in the film’s opening sequence was to Mark and not Bob. Celia’s narration has a stream-of-consciousness quality to it, inviting some comparisons with the narrational strategies of modernist novels such as, for example, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) or James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). ‘I remember, long ago, I read a book that told the meaning of dreams’, Celia begins as the film opens, ‘This is no time to think of danger. This is my wedding day’. As, onscreen, Celia steps from the shadows in her wedding dress, offscreen she narrates: ‘My heart is pounding so. The sound of it drowns out everything. It’s said that when you drown your whole life passes before you like a fast movie’, and with this – before we see the groom – the picture cuts abruptly to the past, with Celia being chastised by her brother for breaking off yet another engagement.

Lang and his cinematographer on Secret Beyond the Door, Stanley Cortez, worked very slowly, with the result that the film overran its production schedule by a significant period of time. Dissatisfied with Lang’s work, the studio drafted William Goetz in to reshoot a good portion of the feature but eventually relented and allowed Lang’s version of the picture to be released to the public. However, it was a commercial failure, losing over a million dollars. Lang himself referred to Secret Beyond the Door as ‘a very unfortunate adventure’, adding that ‘If one thing goes wrong with a project, everything goes wrong; and this one went wrong from the beginning’ (Lang, quoted in Higham & Greenberg, 1969: 115). ‘I don’t know whose fault it is’, Lang reflected, ‘probably much of it was mine. The cameraman was very bad; Joan Bennett wanted to divorce her husband—lots of things went wrong like that’ (Lang, quoted in ibid.). Speaking in 1969, Lang still felt that the basic premise was good but wasn’t developed in the best way possible (Lang, in ibid.: 115-6).  The film began as a ‘Museum Piece No. 13’, a story by Rufus King that was serialised in the women’s magazine Redbook. Sylvia Richards, who was in a romantic relationship with Lang at the time, was asked by the director to adapt the story into a screenplay, with a story that – at the time of Secret Beyond the Door’s original release – invited comparisons with Hitchcock’s then-fairly recent 1940 screen adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s novel Rebecca. Comparisons with the folk tale of Bluebeard were perhaps more apt, however. Interestingly, and somewhat darkly, Lang’s association with the Bluebeard-inspired project, about a man who may or may not have murdered his previous wife, contained echoes of Lang’s own relationship with his first wife, Lisa Rosenthal. Rosenthal died by a gunshot wound to the chest in 1921 not long after finding Lang in flagrante delicto with his then-mistress, Thea von Harbou. Rosenthal’s body was found in a bathtub; the gun that fired the fatal shot was the sidearm Lang had carried in the First World War, a Browning, which Lang had kept as a memento. Rosenthal’s death was ruled a suicide, though for years afterwards Lang was dogged by rumours that he murdered her, an accusation that some suggested was supported by witnesses who claimed they saw Lang shoot Rosenthal during a heated argument. The film began as a ‘Museum Piece No. 13’, a story by Rufus King that was serialised in the women’s magazine Redbook. Sylvia Richards, who was in a romantic relationship with Lang at the time, was asked by the director to adapt the story into a screenplay, with a story that – at the time of Secret Beyond the Door’s original release – invited comparisons with Hitchcock’s then-fairly recent 1940 screen adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s novel Rebecca. Comparisons with the folk tale of Bluebeard were perhaps more apt, however. Interestingly, and somewhat darkly, Lang’s association with the Bluebeard-inspired project, about a man who may or may not have murdered his previous wife, contained echoes of Lang’s own relationship with his first wife, Lisa Rosenthal. Rosenthal died by a gunshot wound to the chest in 1921 not long after finding Lang in flagrante delicto with his then-mistress, Thea von Harbou. Rosenthal’s body was found in a bathtub; the gun that fired the fatal shot was the sidearm Lang had carried in the First World War, a Browning, which Lang had kept as a memento. Rosenthal’s death was ruled a suicide, though for years afterwards Lang was dogged by rumours that he murdered her, an accusation that some suggested was supported by witnesses who claimed they saw Lang shoot Rosenthal during a heated argument.

In the film, Mark is obsessed with the idea that rooms can affect the attitudes and even behaviour of the people who live in them, to such an extent that he believes certain rooms can drive their owners/inhabitants to murder. (‘Certain rooms cause violence, even murder’, he tells Celia.) In his house, Mark has assembled his own ‘black museum’ of ‘murder rooms’, which he shows to his guests during a party: a replica of the room in which Count Guise murdered his wife Celeste after discovering she was secretly a Huguenot; a carbon copy of a room in which a man murdered his mother by tying her to a chair whilst the room flooded. Mark shares all of these rooms bar one, Room 7, which fascinates Celia to such an extent that she steals Mark’s key and secretly makes a duplicate of it. Celia enters the room and initially believes it to be a replica of the bedroom of Mark’s first wife, the deceased Eleanor. However, she soon realises that it is in fact a replica of her own bedroom.  The house, with its ‘murder rooms’, thus becomes a metonym of the mind of its owner; architecture and the psyche (or subconscious) seem to be linked inextricably. Parallels may be drawn with the House of Usher in Edgar Allan Poe’s 1839 short story ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, which ‘dies’ at the same time as its owner Roderick Usher. Like the House of Usher, of course, Mark’s home must be destroyed, and it is consumed by fire in the film’s closing sequences – during which Lang insisted that his principal actors, and not stunt doubles, charge through the burning hallways. However, this takes place after Mark’s peculiar pathology is given a lengthy explanation by way of reference to an incident from his childhood in which Mark’s sister locked him in a room; believing his mother to have done this, the incident twisted Mark into hating all women, oscillating between an even temper and a cruel, tempestuous rage. The house, with its ‘murder rooms’, thus becomes a metonym of the mind of its owner; architecture and the psyche (or subconscious) seem to be linked inextricably. Parallels may be drawn with the House of Usher in Edgar Allan Poe’s 1839 short story ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, which ‘dies’ at the same time as its owner Roderick Usher. Like the House of Usher, of course, Mark’s home must be destroyed, and it is consumed by fire in the film’s closing sequences – during which Lang insisted that his principal actors, and not stunt doubles, charge through the burning hallways. However, this takes place after Mark’s peculiar pathology is given a lengthy explanation by way of reference to an incident from his childhood in which Mark’s sister locked him in a room; believing his mother to have done this, the incident twisted Mark into hating all women, oscillating between an even temper and a cruel, tempestuous rage.

Like The Dark Mirror, the explanation given for Mark’s behaviour is convoluted, evolving out of a sequence in which Mark imagines himself being tried for Celia’s murder, cross-examined by himself, in a courtroom in which the jury’s faces are hidden by shadows. Again, it’s the kind of denouement that Hitchcock satirised in Psycho, and like that picture Secret Beyond the Door foregrounds Freudian theory and, in particular, its grounding in the Oedipus complex – Mark’s perceived ‘betrayal’ by his mother as a child leading him on to a spiral of cruel behaviour in adulthood. When Mark shows the guests at his party the ‘murder rooms’, one of them, who is studying psychology at university, suggests that it isn’t the rooms that led their inhabitants to commit murder but rather the subconscious motivations of the murderer. Mark scoffs at this notion, but the climax of the film seems to validate the theory put forwards by this young woman.

The Big Combo (Joseph H Lewis, 1955) The Big Combo (Joseph H Lewis, 1955)

Detective Lionel Diamond (Cornel Wilde) has spent six months and almost $20,000 investigating Mr Brown (Richard Conte), the head of the ‘big combo’. However, Diamond is not simply dedicated: he’s obsessed with the idea of ‘rescuing’ Brown’s moll, a pretty former pianist named Susan Lowell (Jean Wallace), who comes from a respectable background. Diamond’s investigation is criticised by his boss, Captain Peterson (Robert Middleton), who believes Diamond’s pursuit of Brown will come to nought. For seven years, Brown – a former prison officer – has been the head of the ‘big combo’; prior to that, the organisation was run by a combination of Brown, Joe McClure (Brian Donlevy) and a man named Grazzi, who is believed to be living in Sicily. Now McClure works for Brown, and Brown seizes every opportunity to remind McClure of his fall from power. When Susan takes an overdose, she ends up in the hospital. Diamond seizes the chance to question her, and she tells him a name that she once saw Brown writing in the moisture on a window: ‘Alicia’. Diamond visits an old flame, a burlesque dancer named Rita (Helene Stanton), and seeks solace in her arms and bed. Rita informs Diamond that the word on the street suggests Brown has placed a price on Diamond’s head. Sure enough, Diamond is picked up by two of Brown’s heavies, Fante (Lee Van Cleef) and Mingo (Earl Holliman). Brown tortures Diamond by using McClure’s hearing aid to deafen the detective, before forcing Diamond to drink hair tonic and dropping him off, drunk, at the home of Captain Peterson. Determined to find out who Alicia is, Diamond visits Bettini, a former member of the syndicate who now lives under an assumed identity. Diamond discovers that Alicia is Brown’s former wife (Helen Walker), who is believed to be living in Sicily with Grazzi but who Bettini insinuates was in fact murdered by Brown in a fit of sexual jealousy. Bettini suggests Nils Dreyer (John Hoyt), a wealthy antiques dealer on the books of Brown’s organisation, has evidence of Brown’s murder of Alicia. Diamond visits Dreyer, but Dreyer is less than helpful. After Diamond leaves, Dreyer is shot dead by McClure. Diamond discovers Alicia is still alive and is living in America, having taken the name ‘Anna Lee Jackson’. He resolves to find her and interview her. However, the stakes are raised when Fante and Mingo are sent to ‘hit’ Diamond and mistakenly kill Rita.  The Big Combo is surprisingly bold in its circumlocutory exploration of themes that were prohibited by the Motion Picture Production Code, a characteristic of many of Lewis’ films. Diamond’s pursuit of Brown is, the film suggests strongly, a product of his pathological desire to ‘rescue’ the ‘pure’ Susan from the clutches of the ‘dragon’ (Brown) because Diamond cannot bear to confront the idea that Susan gets pleasure from sleeping with Brown (‘You can’t bear to think of her in the arms of this hood’, Peterson tells Diamond). Diamond’s quest is therefore underpinned by sexual jealousy, and as Brown reminds Diamond, ‘Diamond, the only trouble with you is you’d like to be me. You’d like to have my organisation, my influence, my fix. You can’t: it’s impossible. You think it’s money; it’s not. It’s personality’. The blonde and bourgeois Susan, a former pianist, is juxtaposed with the brunette and proletarian Rita, a burlesque dancer. The former is unavailable to Diamond; the latter is very much available, the film suggesting obliquely that Rita is a hooker. (When they meet for the first time in six months, Rita is angry with Diamond and tells him ‘If you want a date, do what the others do and call me first... a week in advance’.) When Diamond asks Rita what draws a woman like Susan to a man like Brown (‘What is there about a hoodlum that appeals to certain women?’), Rita tells him bluntly that ‘A woman doesn’t care about how man makes his living, only how he makes love’. Lewis cuts to a scene in which Susan and Brown bicker, Susan expressing her disgust at Brown and Brown telling Susan ‘I’ll give you anything at all’ before kissing her neck and moving down her body, out of frame, as Susan’s expression turns from one of anger to ecstasy. The moment is striking in suggesting the act of cunnilingus – that what keeps Susan tethered to Brown is Brown’s sexuality. (This scene caused much consternation at the Production Code office, and initially there were demands that it be removed from the picture, until Lewis pointed out that nothing is depicted explicitly and that any suggestion that Brown is performing cunnilingus on Susan was in the mind of the beholder.) In another scene, Lewis suggests that Fante and Mingo are involved in a homosexual relationship. A telephone rings in a dark room, and Fante answers it, shirtless and leaning out of his bed. We presume he is alone, until we hear Mingo’s sleepy voice and the rear of Mingo’s head, in silhouette, appears in the foreground. The Big Combo is surprisingly bold in its circumlocutory exploration of themes that were prohibited by the Motion Picture Production Code, a characteristic of many of Lewis’ films. Diamond’s pursuit of Brown is, the film suggests strongly, a product of his pathological desire to ‘rescue’ the ‘pure’ Susan from the clutches of the ‘dragon’ (Brown) because Diamond cannot bear to confront the idea that Susan gets pleasure from sleeping with Brown (‘You can’t bear to think of her in the arms of this hood’, Peterson tells Diamond). Diamond’s quest is therefore underpinned by sexual jealousy, and as Brown reminds Diamond, ‘Diamond, the only trouble with you is you’d like to be me. You’d like to have my organisation, my influence, my fix. You can’t: it’s impossible. You think it’s money; it’s not. It’s personality’. The blonde and bourgeois Susan, a former pianist, is juxtaposed with the brunette and proletarian Rita, a burlesque dancer. The former is unavailable to Diamond; the latter is very much available, the film suggesting obliquely that Rita is a hooker. (When they meet for the first time in six months, Rita is angry with Diamond and tells him ‘If you want a date, do what the others do and call me first... a week in advance’.) When Diamond asks Rita what draws a woman like Susan to a man like Brown (‘What is there about a hoodlum that appeals to certain women?’), Rita tells him bluntly that ‘A woman doesn’t care about how man makes his living, only how he makes love’. Lewis cuts to a scene in which Susan and Brown bicker, Susan expressing her disgust at Brown and Brown telling Susan ‘I’ll give you anything at all’ before kissing her neck and moving down her body, out of frame, as Susan’s expression turns from one of anger to ecstasy. The moment is striking in suggesting the act of cunnilingus – that what keeps Susan tethered to Brown is Brown’s sexuality. (This scene caused much consternation at the Production Code office, and initially there were demands that it be removed from the picture, until Lewis pointed out that nothing is depicted explicitly and that any suggestion that Brown is performing cunnilingus on Susan was in the mind of the beholder.) In another scene, Lewis suggests that Fante and Mingo are involved in a homosexual relationship. A telephone rings in a dark room, and Fante answers it, shirtless and leaning out of his bed. We presume he is alone, until we hear Mingo’s sleepy voice and the rear of Mingo’s head, in silhouette, appears in the foreground.

The Big Combo is as stark in its depiction of violence as in its representation of sexuality. When Fante and Mingo capture Diamond, he awakens tied to a chair. McClure pays Fante and Mingo a hundred dollars each, so that they will turn a blind eye whilst McClure questions Diamond. McClure slaps Diamond around a little, asking him questions. Brown walks in, however, and suggests that McClure’s methods are a little too rough-edged and lack precision. Brown knows how to torture a man into revealing information without leaving marks upon the man’s body; the film’s revelation that Brown is a former prison officer who fell in with Grazzi and McClure’s ‘combo’ offers a subtle suggestion that Brown learned his most sadistic skills within the context of his work in law enforcement. Brown takes McClure’s hearing aid and places it in Diamond’s ear, questioning him and allowing Mingo to scream into it before playing loud music on a wireless, the agony driving Diamond into unconsciousness. Later, in the film’s final sequence, Brown has Fante and Mingo turn their submachine guns on McClure. Brown removes McClure’s hearing aid and Lewis cuts to a point-of-view shot from McClure’s perspective as Fante and Mingo’s guns fire silently. Finding its echo in the silent execution of Paul Newman’s character in Sam Mendes’ Road to Perdition (2002), this is one of many inventive moments in this exceptional film noir.  Like Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success (1957), made a couple of years later, The Big Combo makes interesting use of verbal ‘ricochet’, Brown often speaking to characters as a way of getting his point across to other characters who are listening and not engaging in the conversation. At different points in the film, Brown does this with both McClure and Diamond. Throughout the picture, Brown’s relationship with McClure is tense. In a position of servitude to Brown, McClure was once his equal or superior; Grazzi’s disappearance left a void in the hierarchy of the ‘big combo’ which Brown filled. Speaking with a boxer, Bennie (Steve Mitchell), who lost his fight, Brown take the opportunity to humiliate McClure in front of Bennie: ‘Take a look at Joe McClure here’, Brown tells the boxer, ‘He used to be my boss. Now I’m his. What’s the difference between me and him? We breathe the same air, sleep in the same hotel. He used to own it. Now it belongs to me. We eat the same steaks, drink the same bourbon. [He holds out his hands.] Look, the same manicure, same cufflinks. But there’s only one difference: we don’t get the same girls. Why? Because women know the difference. They got instinct’. Brown continues by declaring aphoristically, ‘First is first, and second is nobody’; this is a line that Brown restates at several points in the film, the maxim seeming to summarise Brown’s philosophy. Then Brown asks Bennie who runs the world: ‘They’re not much different from you’, Brown says, ‘Only they’ve got it and you haven’t. I’ve got it, and he [McClure] hasn’t. What makes the difference? Hate! Hate is the word, Bennie! Hate the man who tries to beat you [….] Hate him till you see red and come out winning the big money; and the girls will come tumbling after’. Shorty afterwards, following Susan’s overdose of pills, Brown visits Susan at the hospital and finds her placed under guard by Diamond. Here, he speaks to McClure within earshot of Diamond, Brown facing McClure but his words meant to ricochet onto the detective. ‘Can’t you see?’, Brown asks McClure after noting that the ‘bus boys in my hotel’ make more than a policeman, ‘He’s [Diamond is] a righteous man’; Brown adds, ‘Joe, tell the man [Diamond] I’m gonna break him so fast he won’t have time to change his pants’. Like Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success (1957), made a couple of years later, The Big Combo makes interesting use of verbal ‘ricochet’, Brown often speaking to characters as a way of getting his point across to other characters who are listening and not engaging in the conversation. At different points in the film, Brown does this with both McClure and Diamond. Throughout the picture, Brown’s relationship with McClure is tense. In a position of servitude to Brown, McClure was once his equal or superior; Grazzi’s disappearance left a void in the hierarchy of the ‘big combo’ which Brown filled. Speaking with a boxer, Bennie (Steve Mitchell), who lost his fight, Brown take the opportunity to humiliate McClure in front of Bennie: ‘Take a look at Joe McClure here’, Brown tells the boxer, ‘He used to be my boss. Now I’m his. What’s the difference between me and him? We breathe the same air, sleep in the same hotel. He used to own it. Now it belongs to me. We eat the same steaks, drink the same bourbon. [He holds out his hands.] Look, the same manicure, same cufflinks. But there’s only one difference: we don’t get the same girls. Why? Because women know the difference. They got instinct’. Brown continues by declaring aphoristically, ‘First is first, and second is nobody’; this is a line that Brown restates at several points in the film, the maxim seeming to summarise Brown’s philosophy. Then Brown asks Bennie who runs the world: ‘They’re not much different from you’, Brown says, ‘Only they’ve got it and you haven’t. I’ve got it, and he [McClure] hasn’t. What makes the difference? Hate! Hate is the word, Bennie! Hate the man who tries to beat you [….] Hate him till you see red and come out winning the big money; and the girls will come tumbling after’. Shorty afterwards, following Susan’s overdose of pills, Brown visits Susan at the hospital and finds her placed under guard by Diamond. Here, he speaks to McClure within earshot of Diamond, Brown facing McClure but his words meant to ricochet onto the detective. ‘Can’t you see?’, Brown asks McClure after noting that the ‘bus boys in my hotel’ make more than a policeman, ‘He’s [Diamond is] a righteous man’; Brown adds, ‘Joe, tell the man [Diamond] I’m gonna break him so fast he won’t have time to change his pants’.

A predominantly studio-bound picture, The Big Combo benefits enormously from John Alton’s photography, and in fact the film is arguably one of the best photographed films noir of the classic period. Alton’s work on the picture, using strong chiaroscuro and filling the studio sets meant to represent exterior locations with swirling fog. The result is a film that looks much more expensively produced than it was, the deep, dark shadows and fog feeling heavily symbolic of the mire and moral turpitude that surround the characters and threaten to engulf them – culminating in the iconic final shot, in which Brown is led away, somewhat pathetically and in contradiction to his previous assertions that he won’t be taken alive, by uniformed police officers as Diamond and Susan walk into the fog. In an introductory essay to John Alton’s Painting With Light, Todd McCarthy argues that this shot ‘makes one of the quintessentially anti-sentimental noir statements about the place of humanity in the existential void’ (McCarthy, 2013: xxxix).

Force of Evil (Abraham Polonsky, 1948) Force of Evil (Abraham Polonsky, 1948)

Joe Morse (John Garfield) is a lawyer working for Ben Tucker (Roy Roberts). Tucker runs a ‘combination’ that leads the illegal numbers racket in New York. Tucker has hired Morse to help push through the legalisation of the numbers racket, with the aim of turning it into a legal lottery. The action begins on the day before the Fourth of July celebrations; on the Fourth, superstition leads thousands of people to place bets on the number ‘776’ (the ‘liberty number’). Tucker plans to fix the results that day so that ‘776’ wins, which will put most, if not all, of the small-time numbers banks out of business. Joe’s brother Leo runs a small numbers bank. Leo has a heart condition and, in his youth, sacrificed his own future to allow Joe to become a lawyer. Joe tries to persuade Leo to come into Tucker’s ‘combination’: otherwise, when ‘776’ hits, Leo will be bankrupted and Joe believes this will drive Leo to his grave. However, Tucker forbids Joe from telling Leo that the result on the Fourth of July will be fixed by the organisation. Meanwhile, the new governor is keen to stamp out illegal gambling in New York. In an attempt to protect his brother from the crash organised by Tucker and his organisation, Joe exploits Hall’s anti-gambling ticket by telephoning the police and having Leo taken into custody. However, Leo’s employees are all arrested too, including Leo’s stenographer Doris (Beatrice Pearson), who to Leo is like a daughter. Upon his release, Leo demands that Joe find work for Doris, who now has a criminal misdemeanour on her record. Joe becomes interested in Doris, and she finds herself attracted to the brooding lawyer. Leo makes the decision to join Tucker’s combination, but some of Leo’s employees feel differently. Leo’s bookkeeper Bauer (Howland Chamberlain) vows to leave the organisation in protest, but he is forced to remain by Tucker, who threatens Bauer’s life. Leaving Leo’s bank, Bauer is approached by Wally (Stanley Prager), a tough who works for Tucker’s rival Bill Ficco (Paul Fix). Ficco wishes to negotiate a merger of his organisation with Tucker’s, and Wally demands from Bauer a list of the locations of the numbers banks that Tucker owns.  Caught between a rock and a hard place, Bauer calls the police and tells them where Leo’s numbers bank is located. Meanwhile, Tucker’s wife (Marie Windsor) informs Joe that Tucker’s telephone has been tapped, and Joe’s telephone may also be tapped. When Leo’s numbers bank is raided, Tucker tries desperately to find out the identity of the informant. Joe asks Tucker to pay Leo off, so that Leo may leave the business; but Bauer arranges to meet Leo in a restaurant. Too late, Leo realises that it’s a trap set by Ficco and his hoods. Wally is shot and killed, brutally, and Leo is taken hostage by Ficco. Desperately aware of his brother’s heart condition, Joe confronts Tucker about Leo’s abduction and realises that Tucker and Ficco are working together. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Bauer calls the police and tells them where Leo’s numbers bank is located. Meanwhile, Tucker’s wife (Marie Windsor) informs Joe that Tucker’s telephone has been tapped, and Joe’s telephone may also be tapped. When Leo’s numbers bank is raided, Tucker tries desperately to find out the identity of the informant. Joe asks Tucker to pay Leo off, so that Leo may leave the business; but Bauer arranges to meet Leo in a restaurant. Too late, Leo realises that it’s a trap set by Ficco and his hoods. Wally is shot and killed, brutally, and Leo is taken hostage by Ficco. Desperately aware of his brother’s heart condition, Joe confronts Tucker about Leo’s abduction and realises that Tucker and Ficco are working together.

Arguably, Polonsky’s work on Force of Evil and Body and Soul (Robert Rossen, 1947), for which he wrote the screenplay, pack a one-two punch without parallel in terms of the films’ depiction of a society riddled with corrupt capitalism. These two pictures are amongst the very best of 1940s films noir. Force of Evil is arguably the definitive picture about gambling and corruption, and Body and Soul is perhaps the best film noir about boxing. Both pictures starred John Garfield, who died tragically young several years later, in 1952, aged only 39. Body and Soul features a wonderful sequence in which Garfield’s character’s mother tells her boxer son to ‘fight for something, but not for money’, and this line of dialogue encapsulates Polonsky’s approach to the corrupting effects of money, which taints and destroys relationships – both romantic relationships and those between parent and child or between siblings (Joe and Leo, for example). As Joe’s partner Hobe Wheelock (Paul McVey) warns Joe, his proximity to Tucker is in danger of corrupting Joe: ‘The moment you start doing business for Tucker, doing Tucker’s business, it’s a different thing, Joe’. However, as Joe reminds Wheelock, ‘Tucker is making me rich, Hobe, and I’m your partner who’s making you rich. I wear his old school tie, and you wear mine. You can buy one for yourself during lunch hour, off any pushcart’. Polonsky’s directorial debut would be followed by his blacklisting (Polonsky refused to co-operate with the HUAC), and subsequent to this Polonsky would not direct another feature film until 1969’s Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here.  Polonsky suggested that Wolfert’s source novel was ‘an autopsy on capitalism’ (Andersen, 2007: 259). In the world of Force of Evil, the numbers game is equated with ‘legitimate’ capitalism: Tucker’s racket is an extension of values of Wall Street, which forms the locations for much of the film’s major points of action. ‘This is Wall Street’, Joe intones in his voiceover over the film’s opening shots, ‘And today is important because tomorrow, July the Fourth, I intend to make my first million dollars; an exciting day in any man’s life’. The numbers banks, Joe tells us in his narration, ‘were like banks because money was deposited there. They were unlike banks because the chances of getting money out were a thousand to one. Those were the odds against winning’. Big business, represented by Tucker and Ficco, tears apart and savage small independent businessman like Leo Morse. Leo sees himself as different from Tucker because he (Leo) has morals: ‘I’m an honest man here’, Leo protests to Joe, ‘not a gangster with that gangster tucker [….] I do my business honest and respectable’. When Leo’s wife Sylvia (Georgia Backus) reminds Joe that Leo once had a real estate business and a garage, Leo reminds Sylvia how corrupt those ‘legitimate’ businesses were: ‘A lot you know’, he says, ‘Real estate business, living mortgage to mortgage; stealing credit like a thief. And a garage. That was a “business”. Three cents overcharge on every gallon of gas. Two cents for the chauffeur and a penny for me. Penny for one thief, two cents for the other. Well, Joe’s here now. I won’t have to steal pennies anymore. I’ll have big crooks to steal dollars for me’. All business, the film suggests, is corrupt: the difference between ‘legitimate’ business and criminal enterprise seems simply to be a matter of scale. When Wally approaches Bauer on behalf of Ficco, Bauer resists and refuses to co-operate with the hoodlums: ‘I don’t want anything to do with gangsters’, Bauer says. ‘What do you mean “gangsters”?’, Wally scoffs, ‘It’s business!’ Polonsky suggested that Wolfert’s source novel was ‘an autopsy on capitalism’ (Andersen, 2007: 259). In the world of Force of Evil, the numbers game is equated with ‘legitimate’ capitalism: Tucker’s racket is an extension of values of Wall Street, which forms the locations for much of the film’s major points of action. ‘This is Wall Street’, Joe intones in his voiceover over the film’s opening shots, ‘And today is important because tomorrow, July the Fourth, I intend to make my first million dollars; an exciting day in any man’s life’. The numbers banks, Joe tells us in his narration, ‘were like banks because money was deposited there. They were unlike banks because the chances of getting money out were a thousand to one. Those were the odds against winning’. Big business, represented by Tucker and Ficco, tears apart and savage small independent businessman like Leo Morse. Leo sees himself as different from Tucker because he (Leo) has morals: ‘I’m an honest man here’, Leo protests to Joe, ‘not a gangster with that gangster tucker [….] I do my business honest and respectable’. When Leo’s wife Sylvia (Georgia Backus) reminds Joe that Leo once had a real estate business and a garage, Leo reminds Sylvia how corrupt those ‘legitimate’ businesses were: ‘A lot you know’, he says, ‘Real estate business, living mortgage to mortgage; stealing credit like a thief. And a garage. That was a “business”. Three cents overcharge on every gallon of gas. Two cents for the chauffeur and a penny for me. Penny for one thief, two cents for the other. Well, Joe’s here now. I won’t have to steal pennies anymore. I’ll have big crooks to steal dollars for me’. All business, the film suggests, is corrupt: the difference between ‘legitimate’ business and criminal enterprise seems simply to be a matter of scale. When Wally approaches Bauer on behalf of Ficco, Bauer resists and refuses to co-operate with the hoodlums: ‘I don’t want anything to do with gangsters’, Bauer says. ‘What do you mean “gangsters”?’, Wally scoffs, ‘It’s business!’

For his part, Joe cannot comprehend the notion that a person’s actions may be motivated by forces other than greed or selfishness. When Doris tells him that she knows ‘it’s not wicked to give and want nothing back’, Joe launches into a monologue: ‘It’s perversion! It’s not natural. To go to great expense for something you want, that’s natural. To reach out to take it, that’s human, that’s natural. But to get your own pleasure from not taking, from cheating yourself deliberately like my brother did today, from not taking… Don’t you see what a black thing that is for a man to do, how it is to hate yourself and your brother, and make him feel that he’s guilty, that I’m guilty?’ Later, after Leo has accepted the arrangement proposed by Tucker’s organisation, he expresses to Joe his desire to escape: ‘I don’t want it [the money], Joe’, he protests, ‘The money I made in this business is no good. I don’t want it back’. ‘The money has no moral opinions’, Joe tells him. ‘I find I do, Joe’, Leo responds, ‘I find I do’.  Ironically, given the importance telephones and wiretaps play within the picture, during pre-production of Force of Evil Polonsky’s own telephone was tapped by the FBI, who were interested in recording Polonsky’s conversations with Ira Wolfert, the author of the film’s source novel, Tucker’s People, published in 1943 (see Pollard, 2015: 96). Polonsky was of course a very outspoken left-winger who, during the 1940s, had held fundraisers for various left-wing groups and publications (ibid.). Ironically, given the importance telephones and wiretaps play within the picture, during pre-production of Force of Evil Polonsky’s own telephone was tapped by the FBI, who were interested in recording Polonsky’s conversations with Ira Wolfert, the author of the film’s source novel, Tucker’s People, published in 1943 (see Pollard, 2015: 96). Polonsky was of course a very outspoken left-winger who, during the 1940s, had held fundraisers for various left-wing groups and publications (ibid.).

Polonsky’s script gives Joe Morse’s voiceover a literate, poetic quality that is mirrored in the film’s expressive use of photography and lighting: the picture features symbolic use of extreme high angle shots to make the characters seem small and powerless in the face of the sheer weight and force of capitalism (represented via the Wall Street locations). Bold chiaroscuro lighting schemes are employed to represent the duplicity and complexity of the characters. Polonsky reputedly gave cinematographer George Barnes a book about Edward Hopper and asked him to replicate aspects of Hopper’s work in his photography for the picture (Duncan, 2015: np). At the end of the picture, Joe descends to the rocks by the river looking for the corpse of his tragic brother Leo, and Barnes uses a wide-angle lens to frame Joe against the George Washington Bridge. Patrick Keating has noted that Barnes’ photography during this scene is strangely reminiscent of Edward Steichen’s photograph of the bridge, but where ‘Steichen had been using the wide-angle and deep-focus technique to demonstrate the compositional merits of straight photography’, Barnes uses the bridge as a ‘metaphor for the modern capitalist city: hard, cold, complex, and vast’ (Keating, 2010: 241).

Video

Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, this 1080p presentation of The Dark Mirror takes up approximately 24Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 85:13 mins. The 35mm monochrome photography includes some optical effects shots which, because they’re opticals, are slightly more degraded than the bulk of the footage. There’s a slight vignette on the left hand side of the frame, suggesting that the full frame era has been exposed. A strong level of detail is present, fine detail being evident in closeups. In terms of damage, the presentation is remarkably clean, with some slight instability in the emulsions in a handful of shots. Contrast levels are very pleasing, with very nicely defined midtones and deep, inky blacks. A solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. There seem to be some missing frames at the reel change approximately 10 minutes into the picture: Stevenson telephones the doctor to ask how Ruth is, and there’s a noticeable ‘jump’ on both the video and audio tracks; the doctor offers a response before Stevenson has even asked his question, suggesting that some frames and a line of dialogue from Stevenson are missing. (Unfortunately, I don’t own a copy of the US Blu-ray release from Olive Films, so cannot offer any comparison with that specific release of this picture.)

Secret Beyond the Door is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, with the film taking up 28Gb of space on the disc allocated to it. The film is also presented in the 1.33:1 ratio, and is uncut with a running time of 98:39 mins. The film has a noticeably softer appearance than The Dark Mirror, which may be owing to the lenses used during production on, more likely, the fact that this seems to be taken from a source removed by a step or two further away from the negative. Damage is negligible, with a few white flecks and specks here and there and some very slight gate weave in one or two scenes. The 35mm monochrome photography has pleasing contrast here, with warm highlights, strong midtones and rich blacks. The grain structure is coarser than The Dark Mirror too, which again suggests the source for this presentation may have been removed from the negative by a degree or two more than the source for the presentation of that picture. The film also benefits from a solid encoded to disc.

The Big Combo is uncut and runs for 87:30 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec; the film takes up 25Gb of space on the disc. Presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, Arrow’s presentation of The Big Combo is excellent. Little to no discernible damage is present throughout the film, except for a few brief scratches and flecks. There are some shots which are slightly soft, though this seems to be a quality of the photography rather than an ‘issue’ with this presentation. (In some scenes, Alton appears to have let the focus drift slightly away from subjects close to the camera in order to carry a greater depth of field.) It’s a beautifully shot film, with nearly every composition being worthy of printing and framing as a still photograph. Strong depth of field is accompanied by striking chiaroscuro lighting, and the 35mm monochrome photography is presented here with excellent contrast. Blacks are deep, rich and inky, whilst midtones are strongly defined and textured. A very crisp level of detail is present throughout the film, and the encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Taking up 22Gb of space on its disc, Force of Evil runs for a brisk 78:35 mins. The film is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original 1.33:1 aspect ratio. This is an excellent presentation. The photography uses much staging in depth, which is communicated superbly on this Blu-ray disc, a strong level of rich, crisp detail being evident throughout the presentation. The monochrome 35mm photography displays beautiful contrast, the film’s chiaroscuro photography being communicated superbly, with rich, deep blacks and very clearly defined midtones. Little to no damage, other than a few flecks and specs, is present throughout the film, and the encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

The Dark Mirror features a LPCM 1.0 mono track which is accompanied by English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track is clean and clear, dialogue audible throughout. The subtitles are for the most part accurate, though one error stands out: when a character states that a piece of paper is folded over, the subtitles erroneously transcribe this as ‘folder [sic] over’. Secret Beyond the Door also has a LPCM 1.0 track and optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track for this film is good though the volume seems very low at times and dialogue can sometimes be a little fuzzy – presumably owing to limitations with the source material. The subtitles are easy to read and free from errors. The Big Combo is presented with a LPCM 1.0 track which is clear and free from issues. Optional English HoH subs are provided, though these have one or two very minor errors (‘Mingo’ transcribed at one point as ‘Mango’, and the phrase ‘No, Lionel’ transcribed as ‘No matter’). Force of Evil has a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is clear and dialogue is audible throughout. The optional English HoH subs are easy to read, accurate and error-free.

Extras

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

The Dark Mirror - Audio commentary by Adrian Martin. Martin provides a detailed, thoughtful consideration of The Dark Mirror, which he defines as a psychological melodrama. He discusses the picture’s context and its place in Siodmak’s career. It’s an excellent, thorough commentary track which delves into the film’s major themes. - ‘Reflections of The Dark Mirror’ (34:05). A new interview with film historian Noah Isenberg, this piece complements Martin’s commentary very nicely, Isenberg exploring the relationship between this film and Siodmak’s other pictures and film noir more generally. - Radio Play (29:56). A wonderful addition, this is the 1950 radio adaptation of the story for Screen Director’s Playhouse, featuring Olivia de Havilland reprising her role/s from the film, and also starring John Dehner and Francis X Bushman. - Gallery (10 images). - The Killers trailer (1:46). This is the trailer for Robert Siodmak’s The Killers, loosely based on Ernest Hemingway’s short story and released by Arrow on Blu-ray in 2014 (and reviewed by us here).  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

Secret Beyond the Door - Audio commentary with Alan K Rode. Alan K Rode, director-treasurer of the Film Noir Foundation and the author of several noir-related books, acknowledges the picture’s ‘chequered’ qualities and explores its relationship with Lang’s other pictures. It’s a detailed and well-researched commentary track that, whilst accounting for the film’s weaknesses, highlights some of the more contentious aspects of the film (eg, Lang’s insistence that the film be narrated in the second person, which was overridden when star Bennett campaigned for a more conventional first person narration). - ‘Barry Keith Grant on Secret Beyond the Door’ (14:22). A new interview with Barry Keith Grant lecturer in Film Studies at Brock University, covers the film’s exploration of some of the key themes of Lang’s work as a film director. - ‘The House of Lang’ (20:11). Filmmaker David Cairns narrates a video essay looking at Lang’s signature style. - Bluebeard Radio Play (20:08). This radio adaptation of Bluebeard was broadcast in 1947 as part of the Let’s Pretend strand, and it stars Bill Adams, Sybil Trent and Gwen Davies. - Gallery (7 images). - Hangmen Also Die trailer (1:47). A trailer for Lang’s 1943 film noir Hangmen Also Die, released in 2016 on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here.  DISC THREE: DISC THREE:

The Big Combo - Audio commentary with Eddie Muller. Muller, the founder of the Film Noir Foundation, talks enthusiastically about The Big Combo and explores the manner in which the picture is a distillation of the paradigms of film noir. Muller explores the film’s use of dialogue and examines its themes. It’s a characteristically excellent track from the ever-reliable Muller. - ‘Geoff Andrew on The Big Combo’ (19:21). In a new interview, Andrew, the film programmer at BFI Southbank, reflects on his first encounter with The Big Combo and talks about some of the film’s themes and its relationship with Lewis’ other pictures. - ‘Wagon Wheel Joe’ (19:02). ‘Wagon Wheel Joe’ was the derogatory nickname Joseph H Lewis attracted owing to his tendency to include wagon wheels in the compositions used in his Westerns – an index of his interest in using interesting and unusual camera angles throughout his career. This video essay reflects on this aspect of Lewis’ career. - Gallery (13 images). - Terror in a Texas Town trailer (1:55). This is a trailer for Lewis’ oddball ‘adult’ Western Terror in a Texas Town, recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here.  DISC FOUR: DISC FOUR:

Force of Evil - Commentary by Glenn Kenny and Faran Smith Nehme. Film critic Glenn Kenny and Nehme, a blogger and writer about film, discuss the origins and production of Force of Evil, exploring the ways in which the film differs from other films noir of the period – including in its use of Garfied’s narration and the foregrounding of on-location footage. - Introduction by Martin Scorsese (3:33). In an archival piece, Scorsese talks about the impact Polonsky’s picture has had on his own work as a filmmaker and discusses the significance of the picture more generally. - ‘An Autopsy on Capitalism’ (37:34). Frank Krutnik narrates a new video essay looking at Force of Evil’s major themes and its dissection of capitalism. - Commentary on Selected Themes. o ‘Down and Down’ (9:02). Krutnik discusses the film’s recurring visual motif of height and the symbolic movement of characters up and down steps, which is coupled with expressive use of high and low angle shots. o ‘The Telephone is a Dangerous Object’ (10:26). Krutnik talks about the film’s use of telephones and the manner in which such devices are, within the film, connected with surveillance, betrayal and danger. - Hollywood Fights Back! radio broadcast (57:51). This 1947 recording, a compilation of two 30 minute recordings originally broadcast on the ABC Radio Network, examines the activities of the Committee for the First Amendment, the group of Hollywood personalities who in October of 1947 flew to Washington to stage a protest against the HUAC hearings. - Body and Soul radio play (59:58). Polonsky’s screenplay is adapted for Lux Radio Theater. This was originally broadcast in November of 1958 and features Garfield reprising his role from Rossen’s film, supported by Jane Wyman and William Keighley. - Gallery (10 images).

Overall

Arrow Academy’s Four Film Noir Classics set is an excellent release. The Dark Mirror and Secret Beyond the Door both emphasise the Freudian undertones (or overtones, in the case of these two pictures) often seen as being at the centre of the world of film noir. The Dark Mirror is an interesting and direct exploration of the theme of doubling which underpins many examples of film noir. Secret Beyond the Door is, in comparison with Lang’s other films noir, disappointing but not without interest; it’s the weakest film in the set, and Lang was among the first to admit its areas of weakness, but it’s an engaging picture nonetheless. The Big Combo and Force of Evil, on the other hand, are rightly considered as belonging amongst the best films noir of the classic period, both of them dealing with themes of organised crime and the doubling of a criminal ‘combination’ with the world of business and capital. The Big Combo benefits greatly from John Alton’s stupendously good photography, and in Force of Evil the expressive qualities of film noir photography come together with Polonsky’s powerfully subversive script to deliver a scathing critique of the corruptive effects of money. (Force of Evil benefits from being watched in proximity to Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul, and it’s a shame that picture isn’t included here.) Arrow Academy’s Four Film Noir Classics set is an excellent release. The Dark Mirror and Secret Beyond the Door both emphasise the Freudian undertones (or overtones, in the case of these two pictures) often seen as being at the centre of the world of film noir. The Dark Mirror is an interesting and direct exploration of the theme of doubling which underpins many examples of film noir. Secret Beyond the Door is, in comparison with Lang’s other films noir, disappointing but not without interest; it’s the weakest film in the set, and Lang was among the first to admit its areas of weakness, but it’s an engaging picture nonetheless. The Big Combo and Force of Evil, on the other hand, are rightly considered as belonging amongst the best films noir of the classic period, both of them dealing with themes of organised crime and the doubling of a criminal ‘combination’ with the world of business and capital. The Big Combo benefits greatly from John Alton’s stupendously good photography, and in Force of Evil the expressive qualities of film noir photography come together with Polonsky’s powerfully subversive script to deliver a scathing critique of the corruptive effects of money. (Force of Evil benefits from being watched in proximity to Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul, and it’s a shame that picture isn’t included here.)

Arrow’s presentations of all four films are very pleasing. Secret Beyond the Door’s presentation is the weakest, but that’s only by degree – all four films find satisfying presentations here, though The Big Combo and Force of Evil arguably have the strongest transfers. These are supported by some excellent contextual material too. This is an excellent release for fans of classic films noir, and is clearly one of the best releases of 2017. References: Andersen, Thom, 2007: ‘Red Hollywood’. In: Krutnik, Frank et al (eds), 2007: “Un-American” Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. Rutgers University Press: 225-63 Duncan, Paul, 2015: Film Noir: Films of Trust and Betrayal (Pocket Essentials). Manchester: Oldcastle Books Higham, Charles & Greenberg, Joel, 1969: ‘Interview with Fritz Lang’. In: Grant, Barry Keith (ed), 2003: Fritz Lang: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 101-27 Keating, Patrick, 2010: Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Columbia University Press McCarthy, Todd, 2013: ‘Through a Lens Darkly: The Life and Films of John Alton’. In: Alton, John, 2013: Painting With Light. University of California Press: xix-xliv Pollard, Tom, 2015: Sex and Violence: The Hollywood Censorship Wars. London: Routledge Full-frame grabs (please click to enlarge): The Dark Mirror

Secret Beyond the Door

The Big Combo

Force of Evil

|

|||||

|