|

|

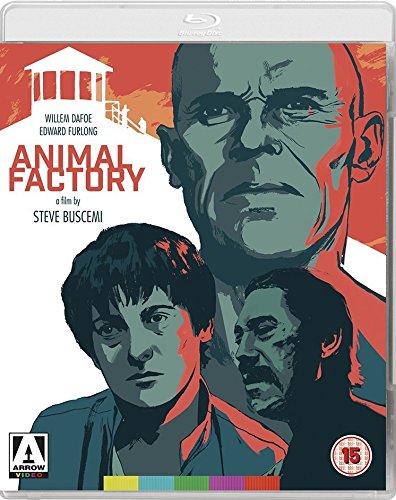

Animal Factory (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th December 2017). |

|

The Film

Animal Factory (Steve Buscemi, 2000) Animal Factory (Steve Buscemi, 2000)

Middle-class young man Ron Decker (Edward Furlong) is incarcerated after being caught with $200,000 worth of marijuana. In prison, Ron shares a cell with transgendered inmate Jan the Actress (Mickey Rourke) and quickly encounters a group which includes Earl Copen (Willem Dafoe), Vito (Danny Trejo) and Paul (Mark Boone Jr). Earl takes quickly to Ron, and knowing Earl has some legal know-how, Ron asks Earl to take a look at his case. When a group of Puerto Rican inmates headed by Psycho Mike (Victor Pagan) plot to lure Ron to a block of the prison that is known for being underpoliced, with the intention of raping the young man, Earl uses his wits to prevent this attack from being carried out. Ron also earns kudos with the other inmates by risking his own neck to warn Vito and Paul, who are making illicit homebrew, that the ‘bulls’ are approaching their hideout. Accused of being a lookout for the homebrew operation, Ron is given a hearing and pleads not guilty. However, at the hearing Ron is warned by the authorities not to make friends or do favours for any convict or ‘Next thing you know, drop your drawers or they’ll throw you to the game’. He is advised by A R Hosspack (Steve Buscemi) to ‘Keep your nose clean, so you can get out of here’.  Earl and his buddies show Ron how to work the system, including how to fake a dislocated shoulder in order to get thirty days’ leave from work details. Earl also manages to score Ron a cushy job working for the Mr Harrell (Michael Buscemi), an educator from outside the prison who runs a literacy programme for the convicts. However, in this role he encounters Buck Rowan (Tom Arnold), a serial rapist. Buck subject Ron to a sexual assault in the lavatories, and Ron can see no answer to this other than to shank Buck; to allow Buck to get away with this crime would make Ron a target for further attacks. Earl and his buddies show Ron how to work the system, including how to fake a dislocated shoulder in order to get thirty days’ leave from work details. Earl also manages to score Ron a cushy job working for the Mr Harrell (Michael Buscemi), an educator from outside the prison who runs a literacy programme for the convicts. However, in this role he encounters Buck Rowan (Tom Arnold), a serial rapist. Buck subject Ron to a sexual assault in the lavatories, and Ron can see no answer to this other than to shank Buck; to allow Buck to get away with this crime would make Ron a target for further attacks.

Earl tries to stop Ron from shanking Buck and intervenes by assaulting Buck; whilst Buck is distracted, Ron sticks a shiv into the rapist’s ribs. However, Ron is unable to follow Paul and Vito’s advice to slit Buck’s throat so that he can’t snitch. Buck survives the attack and is taken to the infirmary, where he identifies Ron and Earl as his attackers. Ron and Earl are subsequently placed in solitary confinement. The DA wants to book Earl for the attempted murder of Buck, but friends of Earl’s manage to place rat poison in Buck’s intravenous drip, killing Buck. Unbeknownst to Ron, Earl’s intervention in the assault on Buck has led to Earl being denied his parole. During a hearing about his own sentence, Ron hears equally bad news, the judge telling him that Ron should remain incarcerated for the protection of society. Meanwhile, in order to avoid being moved to another facility, Earl fakes insanity by pretending to eat his own shit and smearing his cell in blood. Reunited with Ron, Earl tells the younger convict of a potential escape route, which will involve enlisting the outside help of Ron’s father (John Heard).  Steve Buscemi’s Animal Factory, the second film directed by Buscemi (after 1997’s Trees Lounge), was based on Edward Bunker’s 1977 novel of the same title. Bunker’s second published book, Animal Factory was largely autobiographical. Notoriously, before becoming an author and later an actor (Bunker also features in Animal Factory, playing a small role as an inmate named Buzzard), Bunker spent 18 years of his life in various prisons before finding a new direction with the publication of his first novel, No Beast So Fierce, in 1973. A novel about armed robbery, No Beast So Fierce drew heavily on Bunker’s own experiences as a criminal, and the rights to a film adaptation were soon purchased by Dustin Hoffman; in 1978, the film adaptation appeared as Straight Time (directed by Ulu Grosbard), and Bunker co-wrote the screenplay, also appearing in the picture. It was his first screen acting role, and until his death in 2005 Bunker would go on to interweave his work as an author with his writing and acting in motion pictures. Steve Buscemi’s Animal Factory, the second film directed by Buscemi (after 1997’s Trees Lounge), was based on Edward Bunker’s 1977 novel of the same title. Bunker’s second published book, Animal Factory was largely autobiographical. Notoriously, before becoming an author and later an actor (Bunker also features in Animal Factory, playing a small role as an inmate named Buzzard), Bunker spent 18 years of his life in various prisons before finding a new direction with the publication of his first novel, No Beast So Fierce, in 1973. A novel about armed robbery, No Beast So Fierce drew heavily on Bunker’s own experiences as a criminal, and the rights to a film adaptation were soon purchased by Dustin Hoffman; in 1978, the film adaptation appeared as Straight Time (directed by Ulu Grosbard), and Bunker co-wrote the screenplay, also appearing in the picture. It was his first screen acting role, and until his death in 2005 Bunker would go on to interweave his work as an author with his writing and acting in motion pictures.

No Beast So Fierce was stark in its unsentimental and authentic depiction of the criminal milieu. Animal Factory achieves a similar level of verisimilitude in its representation of the lives of convicts, and if its plot elements seem overly familiar to modern readers, it’s possibly because so many examples of prison fiction since the publication of Bunker’s novel have drawn on its rich use of prison slang and matter-of-fact depiction of the realpolitik of the lives of convicts. (It’s hard to imagine HBO’s series Oz, for example without Animal Factory.) It’s perhaps churlish to say, without having direct experience of prison oneself, that Animal Factory is the most realistic prison novel ever written, but I have a friend and former student who, speaking from a position of having spent a number of years in prison himself, claimed that the most authentic depictions of prison life were Bunker’s novel and Dick Clement and Ian Le Frenais’ sitcom Porridge (BBC, 1974-77). (The slightly lesser-known Malcolm Braly’s On the Yard, published in 1967, is perhaps equal in its realism, its author having spent a number of years incarcerated in Folsom Prison and San Quentin.)  Buscemi’s film adaptation of Bunker’s novel was shot on location at Holmesburg Prison in Pennsylvania, and many of the extras were themselves prisoners at Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility. Elsewhere, the film is populated with recognisable faces, including Danny Trejo, who met Bunker for the first time in 1962 and again in San Quentin in 1965. Trejo had boxed in prison, and remembering Trejo’s skill as a boxer Bunker helped Trejo find a job training actor Eric Roberts for Roberts’ role in Andrei Konchalovsky’s Runaway Train (1985, for which Bunker worked on the screenplay). Konchalovsky saw potential in Trejo and offered him a larger role in the picture, propelling Trejo into an acting career (see Quinones, 2005: np). Trejo co-produced Animal Factory with Bunker. Buscemi’s film adaptation of Bunker’s novel was shot on location at Holmesburg Prison in Pennsylvania, and many of the extras were themselves prisoners at Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility. Elsewhere, the film is populated with recognisable faces, including Danny Trejo, who met Bunker for the first time in 1962 and again in San Quentin in 1965. Trejo had boxed in prison, and remembering Trejo’s skill as a boxer Bunker helped Trejo find a job training actor Eric Roberts for Roberts’ role in Andrei Konchalovsky’s Runaway Train (1985, for which Bunker worked on the screenplay). Konchalovsky saw potential in Trejo and offered him a larger role in the picture, propelling Trejo into an acting career (see Quinones, 2005: np). Trejo co-produced Animal Factory with Bunker.

One of the standout performances in the film comes from Mickey Rourke, who essays the role of Jan the Actress, Ron’s transgendered cellmate. Rourke gives Jan a Southern drawl, his face caked in makeup and his clothing offering a parody of femininity. In interview with Theodore Hamm, Bunker singled out Rourke’s performance for praise, admitting that he was ‘mostly’ pleased with the film adaptation of his novel and, particularly, Dafoe’s performance as Earl. Bunker suggests, however, that Edward Furlong ‘just didn’t understand the part’, but nonetheless Buscemi ‘was my first choice as a director, and he really captured the emotional and psychological part of the relationship between the two leads, which is really kind of homoerotic, a love story without sex. But he toned down a couple of racial conflicts, though. I think he feared not being politically correct’ (Bunker, quoted in Hamm, 2000: np). Some of these elements are still present in the picture: for example, in what is perhaps the film’s most frightening sequence, Ron witnesses a strike organised by black inmates. When a Hispanic inmate tries to cross the picket line not to break the strike but simply to get his work card signed, he is rounded on and beaten presumably to death. Black inmates then begin to shank various white inmates for minor ‘infractions’ such as personal debts. The rifle-carrying guards retreat to the towers on the rooftops, and the situation seems destined to escalate into a full blown race riot; it is only averted when gunshots ring out and the guards shoot to kill selected inmates.  In mentioning the aspects of the novel which were ‘toned down’, Bunker seems also to be referring to Earl’s association with the White Brotherhood, which is foregrounded in the novel but is depicted elliptically in Buscemi’s film adaptation, and the racial tensions that threaten to erupt at several points in the story. Like Bunker’s novel, the film is about the manner in which the prison system can take a young man and turn him into a ‘seasoned’ criminal by throwing him into the ‘animal factory’ of the title. Prison seems set to make Ron into a similar character to Earl and his friends. Ron’s initial incarceration seems largely political: his defence lawyer tells him he’s being convicted simply because it’s an election year. However, once inside the prison Ron becomes tainted by his status as a convict. When he presents himself for parole, the judge tells Ron ‘I believe you are a dangerous man. Whether you were already that or became it in prison is immaterial. Our main issue is the protection of society’. In mentioning the aspects of the novel which were ‘toned down’, Bunker seems also to be referring to Earl’s association with the White Brotherhood, which is foregrounded in the novel but is depicted elliptically in Buscemi’s film adaptation, and the racial tensions that threaten to erupt at several points in the story. Like Bunker’s novel, the film is about the manner in which the prison system can take a young man and turn him into a ‘seasoned’ criminal by throwing him into the ‘animal factory’ of the title. Prison seems set to make Ron into a similar character to Earl and his friends. Ron’s initial incarceration seems largely political: his defence lawyer tells him he’s being convicted simply because it’s an election year. However, once inside the prison Ron becomes tainted by his status as a convict. When he presents himself for parole, the judge tells Ron ‘I believe you are a dangerous man. Whether you were already that or became it in prison is immaterial. Our main issue is the protection of society’.

Prison builds and corrupts relationships, the narrative tells us; Earl and Ron’s relationship is initially fraught with suspicion, Ron (and the audience) wondering whether Earl might be taking the younger man under his wing in order to turn him into his ‘punk’ or ‘bitch’. ‘I’m not a punk’, Ron tells Earl, with Earl joking that ‘We change all that in no time’. However, soon the pair’s relationship comes to resemble that of a father and son, with Earl fulfilling the role of Ron’s largely absent father (played by John Heard). Earl struggles to articulate his protective feelings for Ron, assuring Ron that he is ‘not scheming […] It’s a need to feel something; something I don’t get from Paul or Vito [….] It’s not about fucking you [….] Last thing you want to get is a jacket as a punk’: such a jacked would follow Ron anywhere, including to another prison, for example. However, whatever friendship Earl and Ron strike up will be impossible to continue outside the prison. When Earl seems to find a way to get early release for Ron, Ron expresses his gratitude, telling Earl, ‘When I get out, I’m gonna be in so fucking debt to you, Earl’. However, Earl reminds Ron, ‘You’ll forget me. That’s standard. Shit, there’s a curtain between in here and out there’. Upon his incarceration, Ron is quickly identified as a ‘fish’. Before sentencing, Ron’s lawyer tells him that at any other time, Ron would most likely not face jail for his crime, but ‘It’s an election year, so they want to make an example out of you’. However, the prosecuting attorney offers a different perspective on Ron’s criminal endeavours, suggesting that ‘If someone with his [Ron’s] level of involvement who has had every advantage and opportunity our society provides doesn’t go to prison, then it would be unfair to send someone who hasn’t had [these] opportunities’. Ron’s arrival in the prison is accompanied with a montage which places the audience in Ron’s shoes, deftly sketching the prison politics and racial cliques which divide the convict population. Earl argues these have changed since his first conviction: ‘It was different then’, Earl tells Ron, ‘You could represent yourself if you got in a beef, but now, shit, you need friends. If you don’t, you pretty much gotta be an impossibly tough guy or sign on as somebody’s punk’.  By contrast, Earl is a seasoned convict, a man who has spent most of his life in prison. Bunker named Earl after the character played by Humphrey Bogart in Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra (1948), a picture that Bunker admired greatly (Bunker, in Hamm, 2000: np). Reading Bunker’s novel, it’s tempting to see Ron and Earl as representative of Bunker himself at different stages in his criminal career: the young man, facing his first conviction and time in prison that hardens him, and the older, seasoned convict who realises that if he is ever released, he will struggle to adapt to life outside prison. ‘I’m worried that that peckerwood [Earl] is just gonna burn his old ass out’, Jan tells Ron, ‘All the rage, the anger. You can’t come in her with that same rage and anger you had when you was twenty and not think it’s gonna blow out your candlelight’. By contrast, Earl is a seasoned convict, a man who has spent most of his life in prison. Bunker named Earl after the character played by Humphrey Bogart in Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra (1948), a picture that Bunker admired greatly (Bunker, in Hamm, 2000: np). Reading Bunker’s novel, it’s tempting to see Ron and Earl as representative of Bunker himself at different stages in his criminal career: the young man, facing his first conviction and time in prison that hardens him, and the older, seasoned convict who realises that if he is ever released, he will struggle to adapt to life outside prison. ‘I’m worried that that peckerwood [Earl] is just gonna burn his old ass out’, Jan tells Ron, ‘All the rage, the anger. You can’t come in her with that same rage and anger you had when you was twenty and not think it’s gonna blow out your candlelight’.

For his part, Earl jokes repeatedly that the period of time he has spent in the prison gives him some ownership over it: ‘This is my prison’, he states, ‘Everybody knows that’. Both Early and a number of other convicts suggest that the time they have spent in the prison makes them immune to the threats and punishments meted out by the authorities. ‘I been here sixteen months’, an inmate named Tank (Mark Webber) tells Ron, ‘They can’t do shit to me. All I do is laugh at ‘em’. Tank’s words are echoed later in the film by Earl, who tells a guard, ‘What are you gonna do, kick my ass? People been doing that for as long as I can remember. You ain’t nothin’!’ In later life, Bunker himself suggested that prison should be a place where younger violent men are kept and educated in preparation for life outside: ‘That may be punitive’, Bunker offered, ‘but it would be like medical quarantine, because the id seems to burn out’ (Bunker, quoted in Hamm, op cit.). ‘People can still come out of prison better, but in spite of the place, not because of it’, Bunker added in the same interview, and this philosophy seems channelled very strongly in Buscemi’s intuitive adaptation of Bunker’s novel (Bunker, quoted in ibid.).

Video

The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film, presented uncut with a running time of 94:31 mins, takes up just over 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film, presented uncut with a running time of 94:31 mins, takes up just over 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc.

Animal Factory was shot on colour 35mm stock. Shot on location at Holmesburg Prison in Pennsylvania, the film’s photography uses predominantly ‘standard’ focal lengths (in the 35mm to 50mm range) to emphasise the cramped conditions within the prison, picking out details and framing across and through objects (the netted wire mesh of the bullpen in the holding facility, for example) rather than staging in depth, and telephoto lenses to convey a theme of surveillance and eavesdropping, the longer focal lengths also helping to separate characters from their surroundings via the use of shallow depth of field. The compositions often emphasise regimentation via symmetrical framing of, for example, shots of convicts spilling out into the yard, hemmed in by the uniform walls of the prison. The source for this presentation is unclear, but it would seem to be an inherited and aged master. The level of detail in the presentation is above that offered by standard definition DVD, but the film looks ‘flat’ and depthless, the grain structure of the 35mm film elements seeming very muted. The palette is washed out and anaemic, though this appears to be a production choice rather than an ‘issue’ with this Blu-ray presentation. Contrast is very good, with midtones offering strong definition, though shadows are often soft and look slightly ‘boosted’. Again, this may be very well be a decision made during the shooting of the picture (although in my admittedly vague memories of viewing a 35mm projection of Animal Factory during the early 2000s, shadows were much deeper and more pronounced). Finally, there’s little to no damage present throughout the picture.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track is fine, offering a good sense of range and depth when needed (eg, when the film’s bassy score appears on the track). The subtitles are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - An audio commentary with Eddie Bunker and Danny Trejo. This excellent commentary track sees long-term friends Bunker and Trejo talking about the film. Their recollections are rich with personal reflections on their own experiences as convicts, these memories framing a strong discussion of the film’s production. - ‘Eddie Bunker: Life of Crime’ (20:50). In a new featurette, Barry Forshaw, the author of several books about crime cinema, looks at Edward Bunker’s career as a novelist and screenwriter/actor. Forshaw talks about his personal encounters with Bunker, describing him as ‘abrasive’ and ‘tough’ and with ‘a strange mixture in his manner of the […] ex-criminal he was and the screenwriter and actor he became’. Bunker, Forshaw says, was happy to be compared with Jean Genet and was also very aware of the similarities between himself and Genet. - The film’s trailer (1:14).

Overall

If the plot elements of Animal Factory might seem familiar, it’s largely because Bunker’s 1977 source novel established the paradigms for so many prison-based stories (in literature, film and television) that followed. Buscemi’s film, like the novel, reaches for an almost universal significance; like many prison films, such as Jules Dassin’s Brute Force (1947), Robert Bresson’s Un condamné à mort s'est échappé (A Man Escaped, 1956) or Jacques Becker’s Le Trou (1960), Animal Factory uses the prison as a metonym for wider society and tensions. Though prison narratives often emphasise the existential potential of their setting (for example, Sidney Lumet’s The Hill, 1965), Animal Factory sometimes strives for the metaphysical, the picture combining tough street slang with very literate aspirations in a manner that mirrored, by most accounts, the character of Edward Bunker: the film ends with Earl quoting the words of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost, ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven’. If the plot elements of Animal Factory might seem familiar, it’s largely because Bunker’s 1977 source novel established the paradigms for so many prison-based stories (in literature, film and television) that followed. Buscemi’s film, like the novel, reaches for an almost universal significance; like many prison films, such as Jules Dassin’s Brute Force (1947), Robert Bresson’s Un condamné à mort s'est échappé (A Man Escaped, 1956) or Jacques Becker’s Le Trou (1960), Animal Factory uses the prison as a metonym for wider society and tensions. Though prison narratives often emphasise the existential potential of their setting (for example, Sidney Lumet’s The Hill, 1965), Animal Factory sometimes strives for the metaphysical, the picture combining tough street slang with very literate aspirations in a manner that mirrored, by most accounts, the character of Edward Bunker: the film ends with Earl quoting the words of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost, ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven’.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Animal Factory offers a presentation that is an improvement on the film’s various DVD releases, though it seems to be based on an older, inherited transfer. The disc includes some good contextual material, porting the absolutely superb commentary with Bunker and Trejo over from the older DVD releases and adding a new interview with Barry Forshaw. It’s an excellent film, given a satisfying Blu-ray release, though with the caveat that there’s room for improvement in the presentation of the main feature. References: Hamm, Theodore, 2000: ‘Interview with Edward Bunker’. [Online.] https://brooklynrail.org/2000/10/film/interview-with-edward-bunker Quinones, Ben, 2005: ‘From the Depths of Hell to Hollywood’. [Online.] http://www.laweekly.com/film/from-the-depths-of-hell-to-hollywood-2140931 Large screen grabs (click to enlarge):

|

|||||

|