|

|

The Film

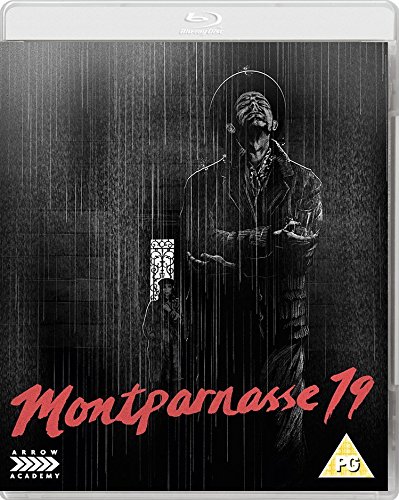

Montparnasse 19 (Jacques Becker and Max Ophuls, 1958) Montparnasse 19 (Jacques Becker and Max Ophuls, 1958)

In 1919, Amadeo Modigliani lives in France, an opening title declaring that ‘Misunderstood and distraut, “Modi” doubted his genius’. “Modi”, as he is known to his friends, has an on-off relationship with the English art critic Beatrice Hastings (Lilli Palmer). He also has contact with another former lover, Rosalie (Lea Padovani), who owns a café, and is friends with his neighbour, the art dealer Leopold Zborowski (Gerard Sety). Modigliani is an alcoholic, drinking from morning until nightfall. At the Academy, Modigliani is introduced to the bourgeois art student Jeanne Hebuterne (Anouk Aimee). Beatrice quickly deduces that Modigliani has fallen in love with Jeanne. However, Jeanne’s father (Jean Lanier) is displeased at her association with Modi, and when Jeanne arranges to meet Modigliani to elope with him, her father locks her in her room. Modi is dismayed when Jeanne does not arrive at their arranged meeting place, and Beatrice tells Modi that he would be doing Jeanne a favour by allowing himself to forget her: ‘You’re absolutely impossible to live with, Modi’, Beatrice asserts. A distraught Modi searches for Jeanne but collapses and is taken to Rosalie’s apartment, where a doctor asserts that Modi’s condition is ‘very serious’ and he must find a place to rest, otherwise he will not live for more than six months.  Modi retires to Nice, where he is seen sketching a prostitute named Lulu (Arlette Poirier). However, her yoyo-wielding pimp Marcel (Robert Ripa) demands Modi pay for his time with Lulu. Modi stands up to Marcel, earning the respect of the pimp, who asks Modi to draw his customers. Modi retires to Nice, where he is seen sketching a prostitute named Lulu (Arlette Poirier). However, her yoyo-wielding pimp Marcel (Robert Ripa) demands Modi pay for his time with Lulu. Modi stands up to Marcel, earning the respect of the pimp, who asks Modi to draw his customers.

To Modi’s surprise, he is reunited with Jeanne, who Lulu spots walking along the street. The return of Lulu sees an elevation in Modi’s fortunes: shortly afterwards, an exhibition of his work is held in a Parisian gallery, until the police intervene and demand a nude study showing pubic hair be removed from public display. Zborowski is approached by an art dealer, Morel (Lino Ventura), who suggests that Modi’s artworks will only acquire value once Modi has drunk himself into oblivion – something which Morel argues is inevitable. Known under a variety of titles, Montparnasse 19 has been released in France under both that title and Les amants de Montparnasse (‘The Lovers of Montparnasse’). The film was originally to have been directed by Max Ophuls, but Ophuls sadly passed away during production and the picture was completed by Jacques Becker. The film would be the penultimate film of Becker himself, the director finishing his career with the excellent Le Trou in 1960, before his death in February of that year. The input of Ophuls and Becker results in a sometimes confused picture, Ophul’s lush period drama clashing with Becker’s preference for film noir-style brooding symbolism.  In The Films of My Life, in reference to Montparnasse 19 Francois Truffaut asked the question, ‘Did the alcoholic genius Modigliani drink because he was a genius, or was he a genius because he drank’ (Truffaut, 1978). Modigliani is introduced in a public house, sketching a proletarian worker in exchange for a round of drinks for Modi and his bohemian friends. However, when Modi completes his portrait and shows it to his subject, the proletarian worker expresses dissatisfaction with it yet still insists on paying for Modigliani’s drinks. Modigliani’s honour has been pricked, however, and he tears up the painting, telling his sitter that as he is dissatisfied with the portrait, he should not pay for it. (Later, after prostitute Lulu expresses surprise at Modi’s strange portrait of her, Modi tells her that ‘I’m not trying to show you as you are but as I see you’.) After this encounter, Modigliani retreats to the bed of the older Beatrice Hastings, who reminds Modi that after his death, ‘No one but the bartenders will remember you, because of all the money you owe for drinks’. In response, Modigliani slaps Beatrice twice across the face, leaving her unconscious as he sneaks out of her apartment. Later, Beatrice will only make an oblique and good-humoured reference to this event, suggesting an element of masochism in her relationship with Modi: ‘You simply don’t beat a woman senseless and leave without saying goodbye’, she jokingly chastises Modi. In The Films of My Life, in reference to Montparnasse 19 Francois Truffaut asked the question, ‘Did the alcoholic genius Modigliani drink because he was a genius, or was he a genius because he drank’ (Truffaut, 1978). Modigliani is introduced in a public house, sketching a proletarian worker in exchange for a round of drinks for Modi and his bohemian friends. However, when Modi completes his portrait and shows it to his subject, the proletarian worker expresses dissatisfaction with it yet still insists on paying for Modigliani’s drinks. Modigliani’s honour has been pricked, however, and he tears up the painting, telling his sitter that as he is dissatisfied with the portrait, he should not pay for it. (Later, after prostitute Lulu expresses surprise at Modi’s strange portrait of her, Modi tells her that ‘I’m not trying to show you as you are but as I see you’.) After this encounter, Modigliani retreats to the bed of the older Beatrice Hastings, who reminds Modi that after his death, ‘No one but the bartenders will remember you, because of all the money you owe for drinks’. In response, Modigliani slaps Beatrice twice across the face, leaving her unconscious as he sneaks out of her apartment. Later, Beatrice will only make an oblique and good-humoured reference to this event, suggesting an element of masochism in her relationship with Modi: ‘You simply don’t beat a woman senseless and leave without saying goodbye’, she jokingly chastises Modi.

The ‘corrupt’ Modigiliani, a known drunk and chaser of women, is contrasted with the respectable and bourgeois Jeanne Hebuterne. ‘She’s not for you’, Modi is told by the art professor at the Academy (Daniel Mendaille), ‘She’s spring water’. ‘Where I come from, there are plenty of fountains’, Modi quips back. Modigliani persuades Jeanne to return home with him, and Becker transitions to the early morning light. Jeanne slouches in an armchair, asleep, whilst seated in a chair opposite her, Modi sketches her. Zborowski enters and asks Modi, ‘Is she a good lover?’ ‘I don’t know’, Modigliani answers, having found his muse. Jeanne swiftly becomes the centre of Modi’s world: ‘I feel anything is possible now’, he asserts, ‘I could paint the whole world. But if I were to pain the whole world, I’d paint a portrait of her’. Jeanne’s disappearance results in Modigliani returning once again to the world of alcohol, and Beatrice reminds him of his time in ‘Montmartre, where you didn’t drink. Your paintings were worthless’.  When an exhibition of Modigliani’s work is staged in a Parisian gallery, a commissaire de police storms into the gallery and demands that the nude study in the gallery’s window, which features (shock, horror) public hair, be removed from public view. Within this sequence, Becker includes a clever reference to French humanist photographer Robert Doisneau’s photo essay/series ‘La vitrine de Romi’ (‘Romi’s Window’) from 1948. The Doisneau photographic series saw the photographer set up a camera in the window of the Romi gallery which enabled him to photograph both those gazing into the window and, to the left of the frame, a painting of a female nude. Doisneau captured some wonderful images containing people’s reactions to the nude study, which speak of attitudes towards nudity and sexuality – and what today would be termed the ‘male gaze’. In one of the photographs, a policeman looks sternly at the exposed derriere of the nude figure; in another (‘La femme indignee’) a middle-aged woman gazes with wide-open eyes and pursed lips which signify her shock at the image. In ‘La regarde oblique’ (‘Sidelong Glance’), a man standing at the window with a woman (presumably his wife) sneaks a sideways glance at the nude study whilst his wife’s attention is directed elsewhere. Montparnasse 19 replicates this imagery in the aforementioned sequence: shooting through the window of the gallery, we see the reactions of the passers-by as they walk past the nude study in the window, including a woman who quickly whisks her husband away. When an exhibition of Modigliani’s work is staged in a Parisian gallery, a commissaire de police storms into the gallery and demands that the nude study in the gallery’s window, which features (shock, horror) public hair, be removed from public view. Within this sequence, Becker includes a clever reference to French humanist photographer Robert Doisneau’s photo essay/series ‘La vitrine de Romi’ (‘Romi’s Window’) from 1948. The Doisneau photographic series saw the photographer set up a camera in the window of the Romi gallery which enabled him to photograph both those gazing into the window and, to the left of the frame, a painting of a female nude. Doisneau captured some wonderful images containing people’s reactions to the nude study, which speak of attitudes towards nudity and sexuality – and what today would be termed the ‘male gaze’. In one of the photographs, a policeman looks sternly at the exposed derriere of the nude figure; in another (‘La femme indignee’) a middle-aged woman gazes with wide-open eyes and pursed lips which signify her shock at the image. In ‘La regarde oblique’ (‘Sidelong Glance’), a man standing at the window with a woman (presumably his wife) sneaks a sideways glance at the nude study whilst his wife’s attention is directed elsewhere. Montparnasse 19 replicates this imagery in the aforementioned sequence: shooting through the window of the gallery, we see the reactions of the passers-by as they walk past the nude study in the window, including a woman who quickly whisks her husband away.

In the later sequences of the film, Lino Ventura’s art dealer, Monsieur Morel, encircles Modigliani like a vulture circling a dying animal. Morel approaches Zborowski and tells him, ‘Your friend [Modi] drinks a lot [….] People like him don’t stop until the day. Then Modi will be big business’. As Modi’s behaviour becomes increasingly self-destructive, Morel’s appearances become more familiar, until immediately prior to Modi’s final collapse, Morel is shown walking behind Modi in a darkened street – like the spectre of death itself.

Video

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Montparnasse 19 presents the film in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and with a running time of 108:31 mins. Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Montparnasse 19 presents the film in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and with a running time of 108:31 mins.

The presentation is very pleasing. The film’s photography is beautiful, the compositions often painterly. The 35mm monochrome photography is communicated very nicely in this HD presentation. Little to no damage is present throughout the picture, and a very crisp and satisfying level of detail is evident, fine detail being present in close-ups. The image has a sense of depth and vibrancy that is facilitated by some excellent contrast: rich and defined midtones are accompanied by balanced highlights, communicating the original photography’s subtle use of light and shade. Black levels are a little less consistent, however. Finally, a strong encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track, in French. This is clean and clear. Optional English subtitles are included, and these are easy to read and seem pretty accurate in terms of their translation of the French dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Jacques Becker and the Artistic Condition’ (57:29). Made by Gaumont for inclusion on the French BD release of Montparnasse 19 a few years back, this documentary contains input from Anouk Aimee, Francoise Fabian, Jean Becker, film historians Olivier Curchod and Denitza Bantcheva. The relationship between Becker and Ophuls is addressed in the context of the response to Lola Montes (1955), as is the difference between Ophuls and Becker’s approaches to filmmaking. Interviewees speak in French, with optional English subtitles. - ‘An Appreciation by Ginette Vincendeau’ (19:49). In this new interview, Ginette Vincendeau talks about Montparnasse 19 and discusses its status as a ‘hybrid’ film – ‘a historical film but […] not a conventional “biopic”’.

Overall

Montparnasse 19 is an interesting picture. As Vincendeau argues in the interview contained on this disc, the film is difficult to categorise as it is neither a conventional historical film nor biopic. There’s a collision between Ophuls’ style and the film noir-esque sensibilities of Becker that makes this picture extraordinarily unique. Its depiction of Modigliani, its protagonist, is also daringly unsympathetic, Gerard Philipe being asked for much of the film to project a character in various states of drunkenness. (In a slightly off-centre example of synchronicity, parallels might be drawn with Rutger Hauer’s performance in The Legend of the Holy Drinker, itself recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow Academy, and reviewed by us here). Montparnasse 19 is an interesting picture. As Vincendeau argues in the interview contained on this disc, the film is difficult to categorise as it is neither a conventional historical film nor biopic. There’s a collision between Ophuls’ style and the film noir-esque sensibilities of Becker that makes this picture extraordinarily unique. Its depiction of Modigliani, its protagonist, is also daringly unsympathetic, Gerard Philipe being asked for much of the film to project a character in various states of drunkenness. (In a slightly off-centre example of synchronicity, parallels might be drawn with Rutger Hauer’s performance in The Legend of the Holy Drinker, itself recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow Academy, and reviewed by us here).

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Montparnasse 19 offers a welcome home video release of a picture that, aside from a handful of television screenings, has been difficult to see in the UK. The Blu-ray presentation is very pleasing and seems to be an improvement on the French BD release from Gaumont. The satisfying presentation of the main feature is accompanied by some excellent contextual material: both the documentary and the interview with Ginette Vincendeau help to provide some context for the main feature. References: Truffaut, Francois, 1978: The Films of My Life. London: Simon and Schuster Screen grabs (click to enlarge):

|

|||||

|