|

The Film

House (Steve Miner, 1985) House (Steve Miner, 1985)

When an elderly woman, Elizabeth Hooper (Susan French), is discovered by a grocery delivery boy to be hanged from a light fitting in her home, her house is inherited by her nephew, horror writer Roger Cobb (William Katt). Roger, who grew up in the house following the death of his mother, is in the middle of writing his latest book, a memoir of his experiences during the war in Vietnam. Roger previously lived in his aunt’s house with his wife, film star Sandy Sinclair (Kay Lenz), and his young son Jimmy (Mark Silver), until Jimmy disappeared whilst swimming in the outdoor swimming pool. This event precipitated the breakdown of Roger’s marriage to Sandy.

Deciding not to sell his aunt’s house but to live in it instead, Roger soon begins to experience strange events, including visions of his aunt Elizabeth. Roger works on his book, experiencing vivid flashbacks to his experiences in Vietnam, including a patrol in which his friend and comrade ‘Big’ Ben (Richard Moll) was badly wounded and begged Roger to kill him so that he would not be taken captive and tortured by the NVA. Roger refused, unable to take his friend’s life, and witnessed Ben being captured by the enemy. Haunted by this memory, Roger also discovers that at the midnight, a portal opens in the closet of one of the bedrooms, allowing a strange monster to escape into the house.

Roger meets his new neighbour Harold (George Wendt). Roger struggles to convince a disbelieving Harold of the strange events he has witnessed in the house, which include hints that Jimmy is alive. One day, Sandy turns up on Roger’s doorstep, but as Roger answers the door to her she turns into a monster; instinctively, Roger shoots the monster, which whilst lying dead on the front porch turns back into Sandy.

The police arrive, alerted by the gunshot, but Roger has hidden the body. When the police leave, Roger is confronted by the Sandy-monster, who tells Roger ‘You’ll never find him [your son]. He’s dead’. The beast is decapitated with a pair of shears which have become animated by the energies within the house, and Roger dismembers the corpse of the Sandy-monster, burying it in the garden. However, as he’s doing this Roger is interrupted by his pretty neighbour Tanya (Mary Stavin), who asks Roger to babysit her young son Robert (Robert Joseph). The police arrive, alerted by the gunshot, but Roger has hidden the body. When the police leave, Roger is confronted by the Sandy-monster, who tells Roger ‘You’ll never find him [your son]. He’s dead’. The beast is decapitated with a pair of shears which have become animated by the energies within the house, and Roger dismembers the corpse of the Sandy-monster, burying it in the garden. However, as he’s doing this Roger is interrupted by his pretty neighbour Tanya (Mary Stavin), who asks Roger to babysit her young son Robert (Robert Joseph).

Whilst Roger looks after Robert, he is terrorised by the severed hand of the Sandy-monster, which has come to life and escaped its grave. Roger manages to avert catastrophe, rescuing Robert. Through examination of a detail in one of the paintings completed by his aunt before her death, Roger deduces the location of a portal within the house which will take him to his son Jimmy.

A haunted house story that follows many of the paradigms set by Stuart Rosenberg’s The Amityville Horror (1979) and Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982), House infuses its horror with a strong seasoning of irreverent, largely physical, comedy. In its mixture of horror and Three Stooges-style slapstick, the picture exhibits some similarities with Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1982); in fact, John Kenneth Muir has argued that House is ‘[s]ort of a middle-class, homogenized Evil Dead’ (Muir, 2007: 509). In the manner in which the second half of the film makes heavy use of rubber monsters which the protagonist can only dispatch by total bodily dismemberment (leading to some blacker-than-black comedy involving a severed hand), House seems in particular to anticipate Raimi’s Evil Dead 2: Dead by Dawn (1987). These similarities become most apparent in the sequence in which Roger kills the Sandy-monster, which morphs from Sandy to a monster and back again. The audience is left wondering how reliable Roger’s perception of events is: is Roger experiencing a hallucinatory psychotic break which has led him to murdering his ex-wife? Raimi achieves a very similar effect in Evil Dead 2, in which Ash’s (Bruce Campbell) interpretation of the strange events at the cabin is opened to interpretation and questioned by the other characters in the film. Like Ash, Roger’s response is to dismember the corpse of his former lover and bury it in the garden. However, even dismembered the monster-corpse displays signs of life: as Roger converses with his pretty neighbour Tanya, the corpse – concealed in a large plastic bag – twitches and threatens to alert Tanya of its presence, a severed hand managing to break free and terrorise Tanya’s young son Robert.

The film struggles to tease out the main conflict, which is between Roger and his memories of the Vietnam War (specifically, the incident involving his ‘betrayal’ of his friend Big Ben), the flashbacks for much of the film’s running time seeming rootless and lacking in direct motivation. John Kenneth Muir suggests that House’s sense of narrative logic is weak (ibid.). However, this is perhaps a criticism that misses the point: the disjointed and unpredictable nature of the portals which appear in the house seem to owe a strong debt to Jean Cocteau’s Surrealist film adaptation of Orpheus (1950), Roger’s journeying between the world of the living and the world of the dead in search of his son mirroring Orpheus’ journey into the underworld in search of his dead wife. House also evidences a fascination with the corps morcele/‘body-in-pieces’ that suggests the influence of Surrealism. The film also seems to make an oblique reference to Bill Stoneham’s famous 1972 Surrealist painting ‘The Hands Resist Him’, in which a young boy and female doll stand in front of a glass-paned door upon which a child’s handprints can be seen; the door is a symbol of the threshold between the ‘real’ world and the world of dreams. In House, Roger’s aunt Elizabeth is an amateur artist who, after her death, leaves behind a number of strange paintings which display some similarities with Stoneham’s technique. One of these paintings, in particular, offers a strange depiction of the house, with a young boy (Jimmy) pressed against an upstairs window, handprints on the glass. Roger interprets this as a symbol of the presence of a portal, leading him to breaking the mirror in the bathroom, through which he reaches and finally rescues Jimmy (after being attacked by a Lovecraftian tentacled beast). The film struggles to tease out the main conflict, which is between Roger and his memories of the Vietnam War (specifically, the incident involving his ‘betrayal’ of his friend Big Ben), the flashbacks for much of the film’s running time seeming rootless and lacking in direct motivation. John Kenneth Muir suggests that House’s sense of narrative logic is weak (ibid.). However, this is perhaps a criticism that misses the point: the disjointed and unpredictable nature of the portals which appear in the house seem to owe a strong debt to Jean Cocteau’s Surrealist film adaptation of Orpheus (1950), Roger’s journeying between the world of the living and the world of the dead in search of his son mirroring Orpheus’ journey into the underworld in search of his dead wife. House also evidences a fascination with the corps morcele/‘body-in-pieces’ that suggests the influence of Surrealism. The film also seems to make an oblique reference to Bill Stoneham’s famous 1972 Surrealist painting ‘The Hands Resist Him’, in which a young boy and female doll stand in front of a glass-paned door upon which a child’s handprints can be seen; the door is a symbol of the threshold between the ‘real’ world and the world of dreams. In House, Roger’s aunt Elizabeth is an amateur artist who, after her death, leaves behind a number of strange paintings which display some similarities with Stoneham’s technique. One of these paintings, in particular, offers a strange depiction of the house, with a young boy (Jimmy) pressed against an upstairs window, handprints on the glass. Roger interprets this as a symbol of the presence of a portal, leading him to breaking the mirror in the bathroom, through which he reaches and finally rescues Jimmy (after being attacked by a Lovecraftian tentacled beast).

John Kenneth Muir also argues that House is part of a key filmmaking trend during the 1980s: ‘By the middle of the Reagan decade, it was suddenly acceptable, even fashionable to discuss the Vietnam War again’ (ibid.). This trend was evident in films as diverse as Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) and Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986). In House, the Vietnam War is referenced via the ‘ghosts’ that haunt the film’s protagonists, conjured through an allegation of cowardice that haunts Roger Cobb. Along with First Blood (George P Cosmatos, 1982) and The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino, 1978), House is – despite its infusion of this theme with outrageous scenes of horror and black comedy – one of a handful of films to deal directly with the emotional/psychological problems facing veterans of the Vietnam War. Fred Dekker, who wrote the original story outline for the picture, originally had a very different set of aims for the film: ‘House was something I conceived as my directing debut; a feature I could do on an extremely low budget. My parents owned an old Victorian house in Marin County, California, so I wrote the story to fit the location! The idea was that a man would go into the house at the beginning, come out at the end, and in between would be eighty-five minutes of the scariest shit I could think of. I wanted it to be very realistic and unsettling, more a character study than a parade of special effects set pieces; something in the vein of early Roman Polanski films or the William Castle shockers I’d loved as a kid’ (Dekker, quoted in Brewton, 2005: np). Dekker became involved in other projects and passed the idea on to Ethan Wiley, who drafted the screenplay in his own way, steering it towards dark comedy (ibid.). The final product, Dekker suggested, was ‘very inventive and sweet, almost a kid’s movie’ (Dekker, quoted in ibid.). Muir argues that although House may be commended for ‘tr[ying] to operate on two thematic tracks, with literal and psychological ghosts equated, […] ultimately the movie is cartoonish and two-dimensional rather than deep or thought-provoking’ (Muir, op cit.: 509). To some extent, in its narrative the film foregrounds this tension between Dekker’s intended character study rooted in the impact of the Vietnam War and the romp-like nature of the horror-comedy it became, Roger’s agent telling Roger, in reference to the book that Roger is writing, ‘Nobody wants to read a book about the goddamned Vietnam War anymore. They want to read a good horror story’.

As in many haunted house films of the 1970s and 1980s, a number of which owe a noticeable debt to Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959), the house in House is suggested to be in some way sentient: ‘It tricked me’, the ghost of Elizabeth tells Roger when he sees her after he moves into the house, ‘I didn’t think it could, but it did [….] It’s going to trick you too, Roger. This house knows everything about you. Leave while you can’. In its exploration of this theme, and the manner in which the house contains portals which allow strange monsters to escape into Roger’s world, there are some similarities between House and Clive Barker’s novella The Hellbound Heart (1986) and subsequent film adaptation Hellraiser (Clive Barker, 1987): in fact, the creature that, at the chime of midnight, escapes from the upstairs closet and attacks Roger bears a striking resemblance to the Wall Crawler/Engineer from Barker’s film. As in many haunted house films of the 1970s and 1980s, a number of which owe a noticeable debt to Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959), the house in House is suggested to be in some way sentient: ‘It tricked me’, the ghost of Elizabeth tells Roger when he sees her after he moves into the house, ‘I didn’t think it could, but it did [….] It’s going to trick you too, Roger. This house knows everything about you. Leave while you can’. In its exploration of this theme, and the manner in which the house contains portals which allow strange monsters to escape into Roger’s world, there are some similarities between House and Clive Barker’s novella The Hellbound Heart (1986) and subsequent film adaptation Hellraiser (Clive Barker, 1987): in fact, the creature that, at the chime of midnight, escapes from the upstairs closet and attacks Roger bears a striking resemblance to the Wall Crawler/Engineer from Barker’s film.

Like many 1980s horror films, House pokes good-natured fun at the fans of horror fiction. After Elizabeth’s funeral, Roger is seen at a book signing with his agent. Shots of Roger at the desk, signing his books, are intercut with point-of-view shots from Roger’s perspective looking up at his fans, the use of a wide-angle lens adding distortion and making Roger’s fans – a ragtag collection of misfits – seem comically threatening as they loom over Roger. ‘Who are these lunatics?’, Roger asks. ‘Your most loyal and devoted fans’, his agent responds.

The film’s horror is located in the trauma of the disappearance of a child: Roger’s young son, Jimmy. (Parallels may perhaps be drawn between House’s association of alternate realities/dimensions and the disappearance of a child with the current popularity of the series Stranger Things, 2016- .) When Roger decides to return to his aunt Elizabeth’s house to live, the film intercuts Roger’s exploration of the house with his memories of the police investigation into the disappearance of Jimmy. Jimmy, it seems, was seen struggling in the outdoor swimming pool, Roger jumping in to save his son but, upon diving below the surface of the water, discovering that Jimmy had vanished. Later, the film reveals Jimmy to have been ‘abducted’ and held hostage in an alternate reality, kept in a bamboo cage in the jungle of Roger’s flashbacks to his time in the Vietnam War, by Roger’s brother-in-arms Big Ben. Big Ben, now a zombie, was motivated by anger at Roger’s refusal to kill the mortally wounded Ben before his capture by NVA forces, resulting in six days of torture by the Vietcong before Ben expired. House thus equates the very personal trauma of the disappearance of Roger’s son Jimmy and the larger cultural trauma of the Vietnam War, and Roger must journey through the portals that the house presents to him, travelling into his memories of the Vietnam War in order to rescue his son.

House II: The Second Story (Ethan Wiley, 1987) House II: The Second Story (Ethan Wiley, 1987)

Where House taps into the popularity of stories about the Vietnam War and its aftermath, House II: The Second Story (Ethan Wiley, 1987) allies itself with the ‘yuppie in peril’ subgenre that was popular during the late 1980s – as evidenced in such films as Something Wild (Jonathan Demme, 1986) and Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985). Many later ‘yuppie in peril’ films climaxed with extended ‘home invasion’ sequences, including Unlawful Entry (Jonathan Kaplan, 1992) and Pacific Heights (John Schlesinger, 1990), and to some extent House II anticipates this trend.

House II begins with a young couple who hand over their baby to another couple in a car before investigating their home, the husband, Clarence (Dwier Brown), carrying a shotgun. The young couple become trapped in a room where they are confronted by a mysterious figure, a spectral Western gunslinger carrying a revolver, who demands ‘I want the skull’ before killing Clarence and his wife.

Twenty-five years later, Jesse (Arye Gross) and his lover Kate (Lar Par Lincoln) arrive at the same house. Jesse is Clarence’s son, the baby from the film’s opening sequence, and was named after his great-great grandfather (Royal Dano), an adventurer. Jesse and Kate are soon joined by Charlie’s gregarious friend Charlie (Jonathan Stark) and his lover Lana (Amy Yasbeck). Kate works for record company executive John (Bill Maher), and Charlie has come to the house in an attempt to persuade Kate to help Lana’s band get a recording contract.

In the basement of the house, Jesse examines photographs of the crystal skull his great-great grandfather (Gramps) discovered during his adventures in Mexico. The skull, it is believed, has mystical qualities and can bestow the gift of eternal life upon its owner. Jesse becomes convinced that the crystal skull, which is missing, was buried with Gramps, and he enlists Charlie’s help in disinterring Gramps. They open Gramps’ grave and are shocked to discover that Gramps is ‘alive’ – and mummified.

Gramps settles in to modern life, Jesse hiding him in the basement of the house. Gramps tells Jesse and Charlie of his nemesis, Slim Reeser (Dean Cleverdon). At a Halloween party thrown at the house, a mysterious hulking caveman, Arnold the Barbarian (Gus Rethwisch) appears and, stealing the crystal skull, escapes through a portal in the house into a prehistoric scene. Gramps implores Jesse and Charlie to pursue him and retrieve the skull. Gramps settles in to modern life, Jesse hiding him in the basement of the house. Gramps tells Jesse and Charlie of his nemesis, Slim Reeser (Dean Cleverdon). At a Halloween party thrown at the house, a mysterious hulking caveman, Arnold the Barbarian (Gus Rethwisch) appears and, stealing the crystal skull, escapes through a portal in the house into a prehistoric scene. Gramps implores Jesse and Charlie to pursue him and retrieve the skull.

Stepping through the portal with an Uzi submachine gun that Charlie happens to have with him(!), Jesse and Charlie find themselves confronted by stop-motion dinosaurs. A creature eats Arnold the Barbarian, and Jesse and Charlie gain possession of the skull – only for it to be scooped away by a pterodactyl, which carries the skull to its nest. Jesse climbs to the pterodactyl nest and retrieves the skull but falls to the ground – and through the floor of a room in the house.

They are accompanied by a cute creature, a hybrid of puppy and chrysalis which Gramps adopts as a pet. However, Gramps is soon attacked by a group of ancient Mayans(?) who steal the skull. An electrician named Bill (John Ratzenberger) arrives and, claiming to have experience of similar situations, accompanies Charlie and Jesse on an adventure through another portal, where they witness the Mayans sacrificing a young woman (Devin Devasquez). They rescue the young woman and also retrieve the skull, returning through the portal to the house. This precipitates the climax of the film, during which Gramps nemesis Slim returns from the dead, and Gramps reveals to Jesse that Slim ‘was the one that killed your ma and pa’. Jesse must confront Slim and secure the crystal skull.

House II amplifies the focus on humour that characterised the first House; in fact, where House can be legitimately labelled as a horror-comedy, House II is primarily a comedy with only a vague relationship with the horror genre. If anything, House II displays even less narrative logic than the first picture, its antagonist and key conflict only being teased out in the film’s closing sequences. The portals which appear in the film, taking Jesse and Charlie back to prehistoric times (when, of course, humans and dinosaurs co-existed) and to what seems to be a Mayan pyramid, seem disconnected and motivated solely by the desire to pastiche various filmic archetypes: in the first case, Ray Harryhausen-style stop motion animation; and in the second case, the depiction of ritualistic sacrifice in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (Steven Spielberg, 1984).

The crystal skull, which a book Jesse finds in the basement suggests can ‘unlock the mysteries of the universe and bring eternal life’ to the person who possesses it, offers a clear allusion to the Mitchell-Hedges crystal skull, discovered in Belize in 1924. Anna Mitchell-Hedges, who claimed to have discovered the skull, asserted that it possessed supernatural qualities, facilitating premonitions and also granting its owner the power to cure cancer or to kill another person. The Mitchell-Hedges skull became an icon of the 1980s when it was used prominently in the titles sequence for Arthur C Clarke’s 1980 television series Arthur C Clarke’s Mysterious World (YTV, 1980) and on the cover of the accompanying book. The skull had previously been discussed in some detail in Erich Von Daniken’s 1968 book Chariots of the Gods: Unsolved Mysteries of the Past, in which Von Daniken claimed the skull was evidence that an alien civilisation had visited Earth thousands of years ago; the skull also made an appearance in the William Shatner-presented documentary Mysteries of the Gods in 1976 (directed by Harold Reinl and Charles Romine). The crystal skull, which a book Jesse finds in the basement suggests can ‘unlock the mysteries of the universe and bring eternal life’ to the person who possesses it, offers a clear allusion to the Mitchell-Hedges crystal skull, discovered in Belize in 1924. Anna Mitchell-Hedges, who claimed to have discovered the skull, asserted that it possessed supernatural qualities, facilitating premonitions and also granting its owner the power to cure cancer or to kill another person. The Mitchell-Hedges skull became an icon of the 1980s when it was used prominently in the titles sequence for Arthur C Clarke’s 1980 television series Arthur C Clarke’s Mysterious World (YTV, 1980) and on the cover of the accompanying book. The skull had previously been discussed in some detail in Erich Von Daniken’s 1968 book Chariots of the Gods: Unsolved Mysteries of the Past, in which Von Daniken claimed the skull was evidence that an alien civilisation had visited Earth thousands of years ago; the skull also made an appearance in the William Shatner-presented documentary Mysteries of the Gods in 1976 (directed by Harold Reinl and Charles Romine).

The skull’s connection with the house is tenuous, the house’s ability to create portals into other worlds unexplained within the story of the film. ‘Remember, boys, this house is a temple, as fantastic as any pyramid or castle you’ll ever see’, Gramps tells Jesse and Charlie, ‘It don’t know time or space or any of that hogwash, but the forces of evil are always after this skill and you’ve got to help me protect it’. Later, the electrician Bill echoes Gramps’ words, asserting ‘These old houses, they got minds of their own. You just got to teach them who’s boss. You know, just sort of give ‘em a spanking’. The sense of Gramps’ culture shock, at finding himself risen again seventy years after his death, is the source of some of the film’s early humour. In an early scene, Gramps makes hit the town but is struck by the realisation that he is essentially a mummified corpse: ‘Look at me’, he asserts despairingly, ‘I’m a hundred and seventy year old fart, a goddamn zombie’. Shortly afterwards, he’s shown channel-surfing, dryly commenting, ‘I hate this goddamned box. Got all them channels and nothing interesting to watch’. He turns to a station showing an old film starring Ronald Reagan: ‘Now you take this Ronald Reagan fellow’, Gramps comments, ‘He sure is a pansy. He wouldn’t have lasted ten minutes back in the old days’.

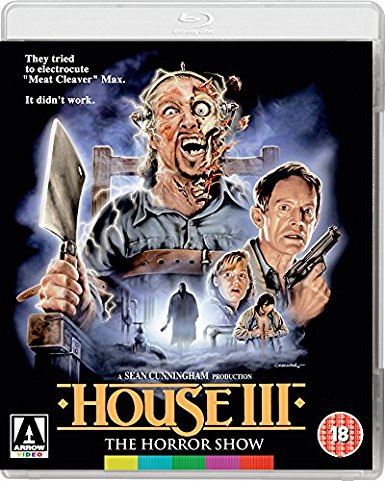

House III: The Horror Show (James Isaac, 1989) House III: The Horror Show (James Isaac, 1989)

Troubled detective Lucas McCarthy (Lance Henriksen) is haunted by his encounter with sadistic and prolific serial killer ‘Meat Cleaver Max’ Jenke (Brion James), who Lucas captured after Jenke had murdered several of Lucas’ colleagues, including his partner Casey (Terry Alexander), and decapitated a young girl with his cleaver.

Having been given desk duty and sessions with a therapist, Dr Tower (Matt Clark), to help cope with the trauma of this event, Lucas is desperate to get back on the streets. He plans to attend Jenke’s scheduled death by electrocution, hoping that this will give him the closure that he needs. However, at the execution Jenke displays a remarkable ability to withstand the electricity that courses through his body, in fact seeming to be energised by it. He breaks free of the bonds that hold him and threatens to come back to haunt Lucas.

Lucas encounters a professor of parapsychology, Peter Campbell (Thom Bray), who warns Lucas that Jenke is ‘coming back for you’ and tells the detective that using a homebuilt electric chair, Jenke trained his body to use electricity to help him achieve a noncorporeal state of existence. Jenke now exists as electrical energy, capable of manipulating reality (or people’s perceptions of reality); the only way to kill him is to subject him to another large jolt of electricity, which will result in Jenke being made mortal again.

Lucas initially rejects Campbell’s claims (‘What are you, some kind of fucking nut or something?’) but at home, Lucas, his wife Donna (Rita Taggart), son Scott (Aron Eisenberg) and daughter Bonnie (Dedee Pfeiffer) begin to experience strange phenomena which are centred around the basement of their home. Lucas receives telephone calls which seem to feature the voice of Jenke tormenting the detective, and when Bonnie’s boyfriend Vinnie (David Oliver) disappears only for his dead body to be found in the basement, Lucas is arrested for murder. Lucas must find a way to escape from captivity and return home, to protect his family from the vengeful spirit of Jenke.

With a script for which one of the co-writers (Allyn Warner) utilised the pseudonym of ‘Alan Smithee’ rather than receive a credit for it, and a production period in which the original director (David Blyth) was replaced a week into shooting, House III is vastly different in tone to the first two entries in the series and has little to connect it to them other than the title. In America, the film was distributed under the title ‘The Horror Show’ with no connection to the House franchise. The film also suffered some problems in postproduction, some graphic effects shots being edited out of the final picture but appearing as promotional stills in various publications, and the ‘R’-rated US release had some of the remaining graphic material removed in comparison with the edit of the film released in Europe. (Both the US and European edits are included on this new Blu-ray release, however.) With a script for which one of the co-writers (Allyn Warner) utilised the pseudonym of ‘Alan Smithee’ rather than receive a credit for it, and a production period in which the original director (David Blyth) was replaced a week into shooting, House III is vastly different in tone to the first two entries in the series and has little to connect it to them other than the title. In America, the film was distributed under the title ‘The Horror Show’ with no connection to the House franchise. The film also suffered some problems in postproduction, some graphic effects shots being edited out of the final picture but appearing as promotional stills in various publications, and the ‘R’-rated US release had some of the remaining graphic material removed in comparison with the edit of the film released in Europe. (Both the US and European edits are included on this new Blu-ray release, however.)

House III’s similarities with Wes Craven’s Shocker, released in the same year, are obvious: both films feature serial killers who use the electric chair to enable them to transcend the physical realm, using their newfound powers to exact revenge on those who were responsible for their capture. House III marries this premise onto a family defence/home invasion plot that is equally indexical of the era in which the picture was made, bringing to mind contemporaneous family defence/home invasion films such as Unlawful Entry, Pacific Heights, Joseph Ruben’s The Stepfather (1987), Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction (1987), Michael Cimino’s remake of The Desperate Hours (1990) and, of course, Chris Columbus’ Home Alone (1990).

Where the first two House films hybridise the genres of horror and comedy, House III marries the paradigms of neo-noir, vogueish at the end of the 1980s/start of the 1990s, to its horror movie stylings. Minus the supernatural elements, the film’s plot – a game of cat-and-mouse between a twisted serial killer and the haunted, troubled cop who captured him – could easily be the plot of an early 1990s neo-noir picture and bears some similarities with the narratives of Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986) and Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (released two years after House III, in 1991). Emphasising the film’s relationship with neo-noir is the excellent photography, which makes striking use of unconventional compositions and film noir-esque chiaroscuro lighting, the actors and sets bathed in sharp contrasts of light and dark. In some ways, House III seems like a dry run for the television series Millennium (Fox, 1996-9), in which Henriksen played haunted FBI profiler Frank Black.

At the start of the picture (in a flashback to the capture of Jenke), Lucas vows to his partner Casey, ‘I’ll put fifteen rounds in the prick. He eats and shits, same as us, right?’ However, Lucas manages to capture Jenke alive, but only after witnessing Jenke decapitate the young girl that Jenke has taken hostage. Jenke is handed over to the authorities, and after an indeterminate prison sentence is to be executed. However, as Professor Campbell explains to Lucas later in the film, Jenke has prepared himself for his execution by electric chair and has plotted to use the electricity to project himself into a different, incorporeal state of being. At the end of the picture, using the method Campbell explained to him, Lucas manages to pull Jenke back into the corporeal world and fulfil the promise he made in the opening sequence, blasting fifteen rounds into Jenke and dispatching the now mortal vicious killer for good. By suggesting that if Lucas had been permitted to kill Jenke instead of capturing him, the subsequent events would have been averted, at the core of House III is a validation of a vigilante-style philosophy that was a feature of many action movies associated with the 1980s. At the start of the picture (in a flashback to the capture of Jenke), Lucas vows to his partner Casey, ‘I’ll put fifteen rounds in the prick. He eats and shits, same as us, right?’ However, Lucas manages to capture Jenke alive, but only after witnessing Jenke decapitate the young girl that Jenke has taken hostage. Jenke is handed over to the authorities, and after an indeterminate prison sentence is to be executed. However, as Professor Campbell explains to Lucas later in the film, Jenke has prepared himself for his execution by electric chair and has plotted to use the electricity to project himself into a different, incorporeal state of being. At the end of the picture, using the method Campbell explained to him, Lucas manages to pull Jenke back into the corporeal world and fulfil the promise he made in the opening sequence, blasting fifteen rounds into Jenke and dispatching the now mortal vicious killer for good. By suggesting that if Lucas had been permitted to kill Jenke instead of capturing him, the subsequent events would have been averted, at the core of House III is a validation of a vigilante-style philosophy that was a feature of many action movies associated with the 1980s.

Whether deliberately or accidentally, however, through its excesses the film frequently veers into the realm of high camp. During the flashback to the capture of Jenke, for example, Lucas is shown wandering through a deserted industrial building (of bizarrely indeterminate function), stumbling across scenes of carnage that are presumably intended to be horrifying but which are so ridiculous they become laughable: a woman’s body in what seems to be a large industrial meat grinder, her legs sticking rigidly out of the funnel and kicking clumsily with each rotation of the barrel; a series of deep fat friers containing a severed hand and a head. The dialogue is also highly camp in its amplification of the stereotypical dialogue of films featuring hardboiled detectives. ‘Get Jenke’, Casey implores whilst hanging from a suspended chain, his arms severed by Jenke’s meat cleaver. ‘I’ll nail his fuckin’ ass’, Lucas responds. When Lucas talks to his wife Donna about his therapy sessions with Dr Tower, she attempts to press upon him the importance of attending them. ‘Don’t get started with that psychiatry shit’, Lucas responds sharply. ‘Luke, you just tried to strangle me’, she reminds him matter-of-factly, ‘Locking Jenke up didn’t make the nightmares stop. Maybe knowing that he’s dead won’t make them stop either’. At his execution, Jenke spits a wafer back at the priest who gives it to him, shouting to Lucas, ‘Your worst fucking nightmare, Lucas. I’m in it’. As he staggers from the electric chair, his skin bubbling and splitting, his body in flames, Jenke tells Lucas, ‘I’m gonna tear your world apart. I’m coming back to fuck you up’.

Like the first House, House III offers a confusion of waking and dream states that is established early in the picture. The flashback to the capture of Jenke is followed by a shot in which Lucas is shown waking from a nightmare, the suggestion being that he relives this horrific experience in his dreams. He embraces his wife, but she transforms into a hideous and bizarre image of Jenke in drag. Jenke then proceeds to bury a cleaver in Lucas’ chest and throttles Lucas, but Lucas awakens again: he’s in bed, struggling against his wife. The cleaver wound in Lucas’ chest will return to haunt him later in the picture, Lucas and Campbell noting that Jenke’s transformation into an incorporeal being having given the serial killer the power to manipulate reality (or people’s perceptions of reality). The bleeding between hallucination and reality shows the influence of Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), in the case of the latter offering a comparison which is consolidated by the image of Lucas’ chest wound, the makeup effects for which are similar to Rick Baker’s effects for the wound which appears in the stomach of Max Renn (James Woods).

House IV: The Repossession (Lewis Abernathy, 1992) House IV: The Repossession (Lewis Abernathy, 1992)

Roger Cobb (William Katt) has clung onto his family home, which now stands empty and partially derelict, despite the protestations of his step-brother Burke (Scott Burkholder), who wants to sell it. Roger has the support of his wife Kelly (Terri Treas) and daughter Laurel (Melissa Clayton). In Roger’s absence, the Cobb house is cared for by Ezra (Ned Romero), a Native American friend of the family. Roger’s grandfather made an agreement with the Native Americans of the area that he would not sell the house, and Roger continues to honour the promise made by his grandfather.

As Roger and his family drive back from the house, one of the tyres on their car blows out and the vehicle overturns. Kelly manages to drag Laurel free, but Roger is trapped. The car bursts into flames. Roger is incinerated but survives; he is taken to a hospital, where he is kept on life support until Kelly makes the difficult decision to have his life support turned off.

After Roger’s death, Kelly vows to take Laurel, who is now in a wheelchair owing to injuries sustained in the crash, and live in the Cobb family house. As they settle in, Kelly makes friends with the eccentric housemaid Verna Klump (Denny Dillon). However, Kelly is haunted by flashbacks to the death of Roger and, specifically, the moment that she signed the paperwork permitting the hospital to remove her husband’s life support.

Burke becomes increasingly aggressive in his pursuit of ownership of the house, but knowing that he wishes simply to sell it or demolish it, Kelly fends him off. Kelly also begins to experience strange visions in the house, including the image of her husband’s arm reaching out to grab her after she accidentally spills his ashes in the hearth.

It is revealed that Burke is working for a sinister man named Mr Grosso (Mark Gash). Grosso is a mob-like figure who runs a corporation specialising in the disposal of toxic waste. He wishes to dispose of a load of illegal toxic waste in the caves beneath Kelly’s home, and this is why Burke has been so desperate to lay his hands on the ownership of the house. It is revealed that Burke is working for a sinister man named Mr Grosso (Mark Gash). Grosso is a mob-like figure who runs a corporation specialising in the disposal of toxic waste. He wishes to dispose of a load of illegal toxic waste in the caves beneath Kelly’s home, and this is why Burke has been so desperate to lay his hands on the ownership of the house.

Released straight to video, House IV taps into the zeitgeist of the early 1990s, with its emphasis on a New Age-style fascination with Native American beliefs (comparable with the roughly contemporaneous television series The X-Files, 1993-2001) and its cynicism towards the yuppies that had been valourised in the previous decade. Roger’s step-brother Burke represents rampant greed and unfettered capitalism, perhaps intentionally sharing his name with the deceitful ‘company man’ played by Paul Reiser in James Cameron’s Aliens (1986). ‘I could turn this place into a goldmine’, Burke tells Roger in reference to the family home. ‘I can’t put a price on my roots’, the grounded Roger responds. ‘You gotta let go of the past, man’, Burke complains. Later, Ezra reveals to Kelly that the house ‘was built on a sacred spring. A healing spring. A shelter for spirits’.

As in the first two films, the house is a place in which the past and present collide or co-exist. ‘There are many memories of the past still sleeping in this house’, Ezra reminds the Cobbs towards the start of the film. The agreement between Roger’s grandfather and the Native Americans is binding and honoured by Roger, Ezra reminding Roger that ‘You have done the right thing. You have honoured your grandfather’s agreement. Now the spirits will rest again’. Roger tells Kelly that his grandfather’s ‘blood oath’ was made ‘on his wedding day’, and that it was ‘A simpler agreement from a simpler time’. Meanwhile, after Roger’s death, Burke becomes increasingly aggressive and threatening in his pursuit of the house, reminding Kelly that ‘Roger’s dead, you’re all alone, and I want this house’. For her part, Kelly remains faithful to the promise Roger made to the Native Americans.

House IV is a more sombre picture than either House or House II, for most of its running time playing like a ‘straight’ haunted house picture. However, the film features some oddball, outrageously comic sequences which jar with the majority of the material, and like the previous films in the series House IV emphasises the slippery relationship between dream and waking reality, between subjective and objective experiences. In one particularly memorably bizarre sequence, Kelly receives a pizza delivered to her doorstep by a singing delivery boy. She is initially confused, not expecting it, but Lauren reveals that she ordered the pizza. Kelly places the pizza box on the kitchen counter and opens it, to reveal a face in the pizza itself (played by Kane Hodder). The pizza proceeds to sing the same ditty sang by the delivery boy, a confused Kelly plunging a knife into it again and again before pushing it into the waste disposal. However, somehow it reaches out and tries to grab Kelly, pulling her into the waste disposal too. Kelly soon realises that this is a hallucination, though, and in response to her mother’s strange mutilation of her meal, Lauren simply asks, ‘Mum?’ ‘Are you happy now?’, Kelly barks back, ‘No anchovies!’ House IV is a more sombre picture than either House or House II, for most of its running time playing like a ‘straight’ haunted house picture. However, the film features some oddball, outrageously comic sequences which jar with the majority of the material, and like the previous films in the series House IV emphasises the slippery relationship between dream and waking reality, between subjective and objective experiences. In one particularly memorably bizarre sequence, Kelly receives a pizza delivered to her doorstep by a singing delivery boy. She is initially confused, not expecting it, but Lauren reveals that she ordered the pizza. Kelly places the pizza box on the kitchen counter and opens it, to reveal a face in the pizza itself (played by Kane Hodder). The pizza proceeds to sing the same ditty sang by the delivery boy, a confused Kelly plunging a knife into it again and again before pushing it into the waste disposal. However, somehow it reaches out and tries to grab Kelly, pulling her into the waste disposal too. Kelly soon realises that this is a hallucination, though, and in response to her mother’s strange mutilation of her meal, Lauren simply asks, ‘Mum?’ ‘Are you happy now?’, Kelly barks back, ‘No anchovies!’

Perhaps the most bizarre sequence, however, involves a depiction of something which, in the context of the narrative, is utterly real: Burke’s visit to Grosso plant, a nightmarish and fantastical place which seems solely to exist for the purposes of putting toxic waste into barrels. (Like Native American beliefs, toxic waste is another aspect of the picture which connects it with the zeitgeist and earlier films such as Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 RoboCop Dan O’Bannon’s 1984 Return of the Living Dead and Chuck Bail’s 1986 Choke Canyon.) Lit like one of the tiers of Hell from Dante’s Divine Comedy, with bold primary coloured lighting gels, the factory scene climaxes with Burke’s visit to Grosso’s office. Grosso’s gatekeeper is a female (horror of horrors), and as if to emphasise the strangeness of the situation, Grosso himself is a wheelchair-bound dwarf, and he lays out the intensity of his desire to acquire Kelly’s home. ‘You can’t stop… progress!’, Grosso spits. A grotesque caricature shot with wide-angle lenses which distort him and make him seem even more excessive, Grosso hacks up a cupful of mucus and has his henchmen force Burke to drink it. It’s a sequence which is more bizarre than any of the hallucinations Kelly encounters, reinforcing the film’s savage denouncement of capitalism and its opposition to family.

Video

All four films are offered 1080p presentations which utilise the AVC codec. Each film is housed on a separate disc.

House takes up 25Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, with a running time of 91:56 mins. The presentation based on a 2k restoration from an interpositive source, the film is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Some controversy surrounding Arrow’s framing of this film has appeared online, owing to the fact that the compositions are opened up slightly in comparison with previous letterboxed home video presentations of this film, featuring more information on the left hand side of the film frame in particular; most contentiously, this has resulted in a handful of shots in which production crew and equipment are fleetingly visible (and weren’t previously). That issue aside, this is an excellent presentation. Little to no damage is present; detail is handled very well, a pleasing level of fine detail being present in close-ups. Contrast levels are very good, with defined midtones tapering off into deep blacks. Colour is also handled very well, the vibrant red of the film’s opening titles being presented nicely and skintones being natural, though there’s a coldness to the greens that seems very slightly ‘off’ (Roger’s lawn has a subtle blue tinge to it at times), though this could simply be down to the lighting and film stocks used during production. Much of the film was shot in fairly low light conditions, presumably on faster stock resulting in a coarse grain structure for many of the night-time scenes. This structure is communicated by an excellent encode to disc.

Taking up just under 23Gb of space on its disc, House II is similarly based on a new 2k restoration of the interpositive. House II is uncut, with a running time of 87:46 mins. This film is also presented in 1.85:1, and the controversies surrounding the framing of House also apply to the first sequel. (Framing along the vertical axis also seems tight in a number of scenes, strangely.) However, in all other respects this is a pleasing presentation, noticeable damage limited to a vertical band which appears on the right hand side of the frame in some shots. The level of detail is pleasing and equivalent to that contained in the presentation of the first film. Contrast is nicely balanced too, midtones possessing definition and shadows containing detail. Colours are once again balanced and seem accurate, and another strong encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Taking up approximately 24Gb of space on its disc, House III features some excellent photography despite the weaknesses of the film’s plot, and photographically it’s arguably the most impressive film of the series. This film offers the viewer the choice of watching either the US ‘R’ rated version (running 94:19 mins) or the uncut European version (running 95:16), the latter inserting the unique footage from the European version into a master derived from the US ‘R’ rated version. These segues are seamless, the differences in the footage from the two sources being imperceptible. Presented in the 1.85:1 screen ratio, the photography for this picture is exceptionally expressive, featuring much use of diffused light in some scenes, and in others very crisp, clinical light and shadows and chiaroscuro lighting effects. All of this is handled very well in this presentation, the balance between light and dark being communicated excellently and plenty of fine detail present in close-ups. In comparison with the US release from Shout! Factory which was plagued with compression-related artifacts and anomalies, Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation features an excellent encode to disc which retains the structure of the 35mm footage.

House IV is a different bag of tricks altogether. The film takes up 25Gb of space on the disc. Arrow’s promotional material suggests this is based on a 2k scan of ‘original film elements’, but at a guess this would seem to be a print rather than a negative or even interpositive source. Contrast is poor, with midtones struggling for definition and blacks/shadow detail often ‘crushed’. In terms of detail, the presentation is exceptionally lo-fi compared with the presentations of the previous films, in particular the third film’s crisp lighting schemes. The image is soft and woolly throughout, lacking fine detail. The film is presented in the 1.85:1 ratio, though House IV was a straight-to-video release. (The picture may very well have been shot with theatrical distribution in mind, however.) The film has a strong encode to disc, but this can’t mitigate the weaknesses of the source material.

Audio

All four films are presented with the same audio options: (i) a LPCM 2.0 stereo track; and (ii) a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track. In the case of House, a LPCM 1.0 track is also included. On House, both the LPCM 1.0 and LPCM 2.0 tracks have depth and are convincing. The 5.1 track adds more sound separation, which is handled effectively, but it has a slightly echoey/reverb-like quality and is very ‘artificial’.

The difference between the 2.0 and 5.1 tracks on House II are similar, with the latter adding more separation effects but still feeling quite artificial and unconvincing. Both tracks have impressive depth and range, however.

The disc containing House III has the same audio options, but in this instance the 5.1 track is much more in keeping with the material, though both it and the stereo track have equally good depth and range.

House IV features much more disappointing audio, however. The same audio options (2.0 and 5.1) are presented, but both tracks are fuzzy and muted, with a reverb-like quality and examples of sibilance dotted throughout.

All four films are accompanied by English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the dialogue.

Extras

DISC ONE:

* House * House

- Audio commentary with writer Ethan Wiley, actor William Katt, director Steve Miner and producer Sean S Cunningham. The participants talk about the origins of the picture and its production, reflecting on the production design and effects and discussing the film’s legacy. It’s a strong track, the recollections by all participants detailed and informative.

- ‘Ding Dong, You’re Dead!’ (66:39). This new documentary contains input from Miner, Cunningham, Wiley, Katt and George Wendt. The interviewees discuss the context in which the film was made and the popularity of horror comedies during the 1980s. They discuss the tension between the ‘underlying dramatic premise’ and the infusion of comedy, also discussing the picture’s relationship with films about the Vietnam War. There’s some overlap with the content of the commentary track, but this is to be expected given the depth and length of this documentary.

- Vintage Making Of (24:07). Shot on videotape, this archival featurette looks at the production of the film and intersperses interviews with the participants with behind the scenes footage and footage from the completed film.

- Still Gallery (6:54).

- Trailers: Trailer 1 (0:59); Trailer 2 (1:28).

- Teaser (1:27).

- TV Spots (x3) (1:31).

DISC TWO:

* House II * House II

- Audio commentary with Ethan Wiley and Sean Cunningham. Wiley and Cunningham are on fine form here, playing off one another with good humour and reflecting in detail on the inception and production of this sequel to the original House.

- ‘It’s Getting Weirder!’ (57:38). A new documentary, this includes comments from Wiley, Cunningham, special effects designer Chris Walas and actors Jonathan Stark and Arye Gross. The participants discuss the film’s relationship with the first picture, Cunningham suggesting that the film was always intended to be ‘a standalone’. They talk about the identity of House II and the introduction of the time travel theme, as well as reflecting on the special effects work in the picture.

- Vintage EPK (14:38). This archival electronic press kit, shot on video, showcases the production of the film and includes onset interviews alongside behind-the-scenes footage.

- Still Gallery (6:41).

- Trailer (1:24).

- TV Spot (0:33).

DISC THREE:

* House III * House III

- Audio commentary with Sean S Cunningham, moderated by Michael Felsher. Cunningham comments on the development and production of the film and its relationship with the other pictures in the series.

- ‘The “Show” Must Go On’ (11:08). Actor and stuntman Kane Hodder is interviewed about his involvement in the picture.

- ‘House Mother’ (10:54). Actress Rita Taggart reflects on the making of House III/The Horror Show.

- ‘Slaughter, Inc.’ (16:01). Robert Kurtzman, Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger discuss the special make-up effects work they produced for House III. This is an excellent piece for those interested in special effects make-up design.

- Behind-the-Scenes Footage (20:57). This is shot on video footage of the film’s production, focusing on the effects sequences and presumably shot (though there is no onscreen contextualisation) by Kurtzman, Nicotero and Berger.

- Workprint Trims (1:23). This brief footage from a workprint of the film is in rough shape and without complete audio. It’s presented without contextualisation but is from the film’s closing sequence and includes a shot of Vinnie’s body not contained in the final edit of the picture.

- Still Gallery (5:19).

- Trailer (1:31).

DISC FOUR:

* House IV * House IV

- Audio commentary with director Lewis Abernathy, moderated by David Gregory. Recorded just over a decade after the production of the film, Abernathy’s comments are strong, and he begins by reflecting on Joe Bob Briggs’ review of the picture. Abernathy discusses the filming locations and conditions in which the picture was made, and talks about its relationship with the other films in the series.

- ‘Home Deadly Home’ (29:24). This new documentary contains input from Abernathy, Cunningham, actors William Katt and Terri Treas, Kane Hodder and composer Henry Manfredini. Cunningham discusses the franchise’s transition from New World to UA and how this impacted on the US title for House III. The participants talk about Abernathy’s work on the picture and his transition from writing to directing, and they talk about the problems posed by Cunningham’s decision to crowbar William Katt’s character from the first picture into the narrative.

- Trailer (3:26).

- Still Gallery (1:50).

Overall

Seemingly by definition, horror-comedies are divisive and often fall flat. For the most part, House manages to balance the horror and comedy elements fairly well, also offering a story that has some relevance to the times in which it was set – though there’s clearly tension between Dekker’s more lofty ambitions for the project and what it ultimately became. Nevertheless, a strong sense of pathos is generated by both Roger’s mourning for his lost son and the manner in which he is haunted by his experiences in Vietnam. Seemingly by definition, horror-comedies are divisive and often fall flat. For the most part, House manages to balance the horror and comedy elements fairly well, also offering a story that has some relevance to the times in which it was set – though there’s clearly tension between Dekker’s more lofty ambitions for the project and what it ultimately became. Nevertheless, a strong sense of pathos is generated by both Roger’s mourning for his lost son and the manner in which he is haunted by his experiences in Vietnam.

House II, on the other hand, is unfocused and dominated by humour. The narrative struggles to find direction, the conflicts only becoming teased out in the final sequences. The film has its ardent fans, however: speaking anecdotally, I remember when this film came out, one of my friends was hugely impressed with it, though when I was presented with the chance to see it, its charms were lost on me. The phrase ‘your mileage may vary’ could have been invented to describe House II, and whether you connect with the film or not will depend on your tolerance for comedy-horror (rather than horror-comedy, if you catch my drift).

House III, with its ludicrous plot delivered so earnestly it strays unintentionally into the realm of high camp, is made watchable by an excellent performance from Henriksen, who invests his character with the gravitas associated with the actor’s roles from his period of his career, and some superb chiaroscuro-style photography. It’s a strange film, sincere in places and almost self-parodic in others, but it’s enlivened by some excellent effects work. (It’s also very much dominated by indices of the era in which it was made which now seem strange: for example, Scott’s fascination with rock bands of the era and the crop top t-shirt he wears for much of the film, a fashion best left in the 1980s.

House IV also struggles with its identity, for the most part presenting itself as a haunted house picture but with some oddball excursions into outrageous comedy. The film is very much of its time, its fascination with toxic waste, evil corporations and Native American mysticism speaking very much of the early 1990s. It’s an interesting film, more sincere than House II but with too many echoes of (or direct allusions to) other horror films of that period. House IV also struggles with its identity, for the most part presenting itself as a haunted house picture but with some oddball excursions into outrageous comedy. The film is very much of its time, its fascination with toxic waste, evil corporations and Native American mysticism speaking very much of the early 1990s. It’s an interesting film, more sincere than House II but with too many echoes of (or direct allusions to) other horror films of that period.

Arrow’s presentations of House, House II and House III are, aside from the documented framing issues with the first two pictures, very pleasing indeed, the films benefitting greatly from their HD presentations – in particular, House III which, despite its narrative weaknesses and clichéd dialogue, is photographed beautifully. The presentation of House IV, on the other hand, is weak and let down by poor quality materials. (The exact ‘film source’ used for this presentation is unclear, but would seem to be a positive print of some sort.) That said, even the presentation of House IV is an improvement over that film’s previous home video releases.

All four films are accompanied by some excellent contextual material, most of it objective in considering the films’ relative merits and weaknesses. Though not a consistently impressive series of films (what is?), the House pictures are rewarding for fans of horror films of the 1980s and early 1990s, offering a shot of nostalgia for those of us who remember seeing these pictures ‘back in the day’, and Arrow’s Blu-ray releases provide the best home video outings these four films have had.

References

Brewton, Billy Ray, 2005: ‘INTERVIEW with FRED DEKKER’. [Online.] http://simplycinema.blogspot.co.uk/2005/06/interview-with-fred-dekker.html?q=fred+dekker Accessed: 5 December 2017

Muir, John Kenneth, 2007: Horror Films of the 1980s. London: McFarland & Company

Large Screen Grabs (Click to Enlarge):

House

House II

House III

House IV

|