|

|

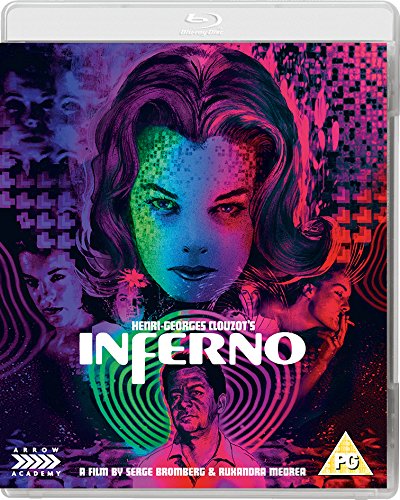

Inferno AKA L'enfer d'Henri-Georges Clouzot (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th February 2018). |

|

The Film

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s ‘Inferno’ (Serge Bromberg, 2009) Henri-Georges Clouzot’s ‘Inferno’ (Serge Bromberg, 2009)

A chance encounter in a broken-down lift with Inès de Gonzalez, the widow of Henri-Georges Clouzot, led filmmaker Serge Bromberg to press de Gonzalez to release the 185 reels (approximately 15 hours) of footage of Clouzot’s unfinished 1964 picture L’enfer (Inferno) for inclusion in a documentary about the production of this ill-fated film. Discovering that the footage either had no soundtrack or featured a soundtrack that was unusable, Bromberg hired two actors, Jacques Gamblin and Bérénice Bejo, to act out some of the dialogue from the script, helping to contextualise the silent footage from Clouzot’s original shoot. Alongside the footage included in his documentary about Clouzot’s project, released in 2009 as ‘L’enfer’ de Henri-Georges Clouzot (Henri-Georges Clouzot’s ‘Inferno’), Bromberg sought out and interviewed some of Clouzot’s collaborators, including actress Catherina Allegret and crew members Costa-Gavras, Jacques Douy, Bernard Stora, William Lubtchansky, Joel Stein, Gilbert Amy, Jean-Louis Ducarme and Nguyen Thi Lam. Clouzot’s L’enfer was to focus on a newlywed couple, hotelier Marcel (Serge Reggiani) and Odette (Romy Schneider). (Their names were a conscious reference to Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu/Remembrance of Things Past, 1913-27.) The older Marcel (Reggiani was 42 when the film went into production) is insecure, riddled with paranoia regarding his younger wide (Schneider was 26) and imagines her in various sexually-charged scenarios, being seduced by the beefcake mechanic Martineau (Jean-Claude Bercq) or in the midst of Martineau’s sexual liaisons with the flirtatious local hairdresser.  Outside France, Clouzot is mostly known for his suspense pictures/thrillers Les diaboliques (1955) and Le Salaire de la peur (Wages of Fear, 1953). However, during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Clouzot and his very prepared, methodical style of filmmaking were criticised by some of the leading figures of the nouvelle vague, who privileged improvisation and a much more ‘raw’ approach to filmmaking. By 1964, when L’enfer went into production, Clouzot was already seen as ‘old school’ in his methods. Perhaps in response to this, Clouzot planned with L’enfer to adopt an experimental aesthetic. L’enfer was to feature heavy use of location shooting (a key paradigm of much work of the nouvelle vague filmmakers) and a mixture of colour and monochrome footage: the bulk of the narrative was to be presented in monochrome, but its protagonist’s paranoid fantasies involving his wife Odette were to be filmed in colour. However, not just any colour stock was to be used: Clouzot had his collaborators shoot numerous tests in order to achieve strange, alienating effects. For example, in a sequence in which Marcel imagines Odette being seduced by Martineau whilst sitting in a boat on a nearby lake, the water of the lake was to turn red; this was to be achieved not by special effects in post-production but entirely in camera, by manipulation of the film stocks and makeup, something which Lubtchansky describes as ‘a Herculean task’. Outside France, Clouzot is mostly known for his suspense pictures/thrillers Les diaboliques (1955) and Le Salaire de la peur (Wages of Fear, 1953). However, during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Clouzot and his very prepared, methodical style of filmmaking were criticised by some of the leading figures of the nouvelle vague, who privileged improvisation and a much more ‘raw’ approach to filmmaking. By 1964, when L’enfer went into production, Clouzot was already seen as ‘old school’ in his methods. Perhaps in response to this, Clouzot planned with L’enfer to adopt an experimental aesthetic. L’enfer was to feature heavy use of location shooting (a key paradigm of much work of the nouvelle vague filmmakers) and a mixture of colour and monochrome footage: the bulk of the narrative was to be presented in monochrome, but its protagonist’s paranoid fantasies involving his wife Odette were to be filmed in colour. However, not just any colour stock was to be used: Clouzot had his collaborators shoot numerous tests in order to achieve strange, alienating effects. For example, in a sequence in which Marcel imagines Odette being seduced by Martineau whilst sitting in a boat on a nearby lake, the water of the lake was to turn red; this was to be achieved not by special effects in post-production but entirely in camera, by manipulation of the film stocks and makeup, something which Lubtchansky describes as ‘a Herculean task’.

Alongside effects such as this, Clouzot became fascinated with kinetic art and shot a significant amount of preproduction test footage incorporating kinetic art and effects inspired by it: lights on rotating rigs cast eerie, moving shadows across the faces of the actors; kaleidoscopic effects were employed that fragmented the action and created repetition within the frame. Lubtchansky says that Clouzot demanded the camera ‘zoom in and out faster and faster’, joking that ‘I had become the specialist of ocular coitus’. Samples of this test footage are included in Bromberg’s documentary, offering a tantalising glimpse of what might have been if Clouzot had been able to complete L’enfer.  Clouzot’s exploration of such techniques was facilitated by Columbia, who invested into the film and gave Clouzot both an extraordinary amount of freedom and the financial resources to exploit his peccadilloes. Lubtchansky says that Clouzot ‘went off into a world of tests that was completely new in French cinema’: the money from the US company ‘wasn’t to have 100,000 horsemen or build huge sets. It was there to secure a creative artist [Clouzot] the possibility of freely experimenting as he wrestled with ideas, to see if they came or not’. Columbia were presumably acting on the international successes of such European ‘art’ pictures as Fellini’s 8½ (1963), a picture with which Clouzot had reputedly been very impressed. The experimental visual design of L’enfer was to be accompanied by an equally unique soundscape; Clouzot hired Jean-Louis Ducarme to create a soundscape intended to support the visual hallucinations of Marcel. Surviving audio recordings feature a cacophony of voices designed to communicate ‘morbid, pathological jealousy’ (as Ducarme describes it). Clouzot’s exploration of such techniques was facilitated by Columbia, who invested into the film and gave Clouzot both an extraordinary amount of freedom and the financial resources to exploit his peccadilloes. Lubtchansky says that Clouzot ‘went off into a world of tests that was completely new in French cinema’: the money from the US company ‘wasn’t to have 100,000 horsemen or build huge sets. It was there to secure a creative artist [Clouzot] the possibility of freely experimenting as he wrestled with ideas, to see if they came or not’. Columbia were presumably acting on the international successes of such European ‘art’ pictures as Fellini’s 8½ (1963), a picture with which Clouzot had reputedly been very impressed. The experimental visual design of L’enfer was to be accompanied by an equally unique soundscape; Clouzot hired Jean-Louis Ducarme to create a soundscape intended to support the visual hallucinations of Marcel. Surviving audio recordings feature a cacophony of voices designed to communicate ‘morbid, pathological jealousy’ (as Ducarme describes it).

Bromberg’s documentary suggests that Clouzot’s picture was to be a study in a curious male psychopathology, narrativised through a story of the crippling sexual jealousy an older man feels towards his younger bride. In archival interview footage, Clouzot himself states that L’enfer was ‘to dramatise the feeling of anxiety that I have every night’. Catherina Allegret, argues that Clouzot’s films generally are about the neurosis of jealousy.  The production stalled when Reggiani became ill one week into production. Clouzot sought to replace him, hiring Jean-Louis Trintignant to play Marcel. However, no footage with Trintignant was ever shot, and production closed when Clouzot experience a heart attack. (The fact that Trintignant was almost ten years younger than Reggiani, and the age gap between Trintignant and Schneider was therefore much smaller, would surely have impacted on the film’s depiction of Marcel’s insecurities.) It seems that Reggiani’s illness had been precipitated by Clouzot’s demand that Reggiani run behind a camera truck for 10 miles per day as part of a sequence for the film. Problems appeared before Reggiani’s illness, though: as explained in Bromberg’s documentary, Clouzot had three camera crews working at his beck and call, but instead of dividing his time amongst them, Clouzot would become fixated on shooting and reshooting certain scenes over and over again. This resulted in two of the crews waiting interminably for Clouzot to move on. On top of this, Clouzot was well known for his insomnia, and with many of the cast and crew staying in the hotel that also functioned as the film’s chief location, this offered Clouzot the opportunity to wake his colleagues up in the dead of night and feverishly talk through the next day’s shooting with them. He was hard on his actors too, his demanding method creating friction between himself, Reggiani and Schneider. Schneider, we are told, would shout at Clouzot, whilst Reggiani would retreat and stew on his juices in private. The production stalled when Reggiani became ill one week into production. Clouzot sought to replace him, hiring Jean-Louis Trintignant to play Marcel. However, no footage with Trintignant was ever shot, and production closed when Clouzot experience a heart attack. (The fact that Trintignant was almost ten years younger than Reggiani, and the age gap between Trintignant and Schneider was therefore much smaller, would surely have impacted on the film’s depiction of Marcel’s insecurities.) It seems that Reggiani’s illness had been precipitated by Clouzot’s demand that Reggiani run behind a camera truck for 10 miles per day as part of a sequence for the film. Problems appeared before Reggiani’s illness, though: as explained in Bromberg’s documentary, Clouzot had three camera crews working at his beck and call, but instead of dividing his time amongst them, Clouzot would become fixated on shooting and reshooting certain scenes over and over again. This resulted in two of the crews waiting interminably for Clouzot to move on. On top of this, Clouzot was well known for his insomnia, and with many of the cast and crew staying in the hotel that also functioned as the film’s chief location, this offered Clouzot the opportunity to wake his colleagues up in the dead of night and feverishly talk through the next day’s shooting with them. He was hard on his actors too, his demanding method creating friction between himself, Reggiani and Schneider. Schneider, we are told, would shout at Clouzot, whilst Reggiani would retreat and stew on his juices in private.

Thirty years later, the scenario for Clouzot’s Inferno formed the basis for Claude Chabrol’s L’enfer (1994). The protagonists were renamed Paul and Nelly, and played by Francois Cluzet and Emmanuelle Beart respectively. Chabrol’s film updates the story but in most other respects remains quite faithful to Clouzot’s original intentions; the glacial style of Chabrol’s films was heavily influenced by Clouzot’s work.

Video

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s ‘Inferno’ is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec and taking up 24.3Gb on the disc. The documentary is in its intended aspect ratio of 1.78:1 and runs for 99:48 mins. Henri-Georges Clouzot’s ‘Inferno’ is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec and taking up 24.3Gb on the disc. The documentary is in its intended aspect ratio of 1.78:1 and runs for 99:48 mins.

The documentary mixes modern digitally-shot interview footage with the 35mm footage and test footage shot by Clouzot for L’enfer. Interspersed throughout the film are still photographs shot on set and 16mm archival interview and behind-the-scenes footage shot by television companies which were on set to document the production. All of this material is presented very well on this Blu-ray release of the documentary. An excellent level of fine detail is present throughout, and the film footage has a very natural, filmlike appearance with defined midtones and balanced highlights. Both the archival monochrome and colour footage is impressively presented on this disc. The digitally shot material has a compressed dynamic range, but that’s a characteristic of the shift from one medium to another rather than an issue with this presentation. This is a solid, very pleasing presentation of Bromberg’s documentary.

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with the option of watching the documentary with a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track or a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both audio tracks are clean, clear and problem free. The 5.1 track has added sound separation but the LPCM 2.0 track is perfectly serviceable. Optional English subtitles are provided.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Lucy Mazdon on Henri-Georges Clouzot and Inferno’ (21:48). Mazdon, Reader in Film Studies at the University of Southampton, locates Clouzot’s films within the ‘quality tradition’ and discusses the similarities between Clouzot’s work and the 1930s neo-realist pictures but with elements of experimentation which ally him with the nouvelle vague. After discussing some of the traits of Clouzot’s films generally, Mazdon reflects on L’enfer and discusses Bromberg’s relationship with the doomed Clouzot project. - Introduction by Serge Bromberg (8:47). Providing an introduction to his documentary, Bromberg speaks in French; optional English subtitles are provided. - ‘They Saw Inferno’ (59:43). This wonderful extra extends Bromberg’s main feature documentary by including further interviews with many of the participants of Bromberg’s documentary and others besides, including Clouzot’s widow. It also includes some additional behind-the-scenes footage of the production. The interviewees speak in French; optional English subtitles are included. - Interview with Serge Bromberg (18:09). Bromberg talks about his relationship with L’enfer, summarising its narrative and discussing its place in Clouzot’s body of work. Bromberg speaks in English in this interview. - Trailer (1:44). - Stills Gallery (42 images).

Overall

Bromberg’s documentary contributes to the mythology surrounding Clouzot’s aborted L’enfer. The documentary itself subtly suggests that Clouzot’s film was an obsession, the making of it a pathological need on the part of the director himself, the narrative an expunging of personal demons comparable with the stories that have been built up around Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Hitchcock’s doomed Kaleidoscope Frenzy project, Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982) or Terry Gilliam’s long postponed adaptation of Don Quixote. As such, Bromberg’s documentary aspires to be placed alongside Burden of Dreams or Hearts of Darkness as a documentary about a director’s obsession, the act of scripting and directing a motion picture depicted as a psychopathological compulsion in which the filmmaker and his endeavours are destroyed by the filmmaker’s own ego. Bromberg’s documentary contributes to the mythology surrounding Clouzot’s aborted L’enfer. The documentary itself subtly suggests that Clouzot’s film was an obsession, the making of it a pathological need on the part of the director himself, the narrative an expunging of personal demons comparable with the stories that have been built up around Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Hitchcock’s doomed Kaleidoscope Frenzy project, Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982) or Terry Gilliam’s long postponed adaptation of Don Quixote. As such, Bromberg’s documentary aspires to be placed alongside Burden of Dreams or Hearts of Darkness as a documentary about a director’s obsession, the act of scripting and directing a motion picture depicted as a psychopathological compulsion in which the filmmaker and his endeavours are destroyed by the filmmaker’s own ego.

Bromberg’s documentary is fascinating, deftly interweaving interviews, newly shot footage and Clouzot’s own test footage and production footage. The documentary weaves a spell of its own. The presentation of the documentary on this Blu-ray release is top notch, and it’s also accompanied by some very substantial extras, the most notable of which is ‘They Saw Inferno’, an hour long compendium of additional interviews and behind-the-scenes footage from the production of L’enfer. For anyone interested in the filmmaking process, this release of Bromberg’s documentary is an essential purchase.

|

|||||

|