|

|

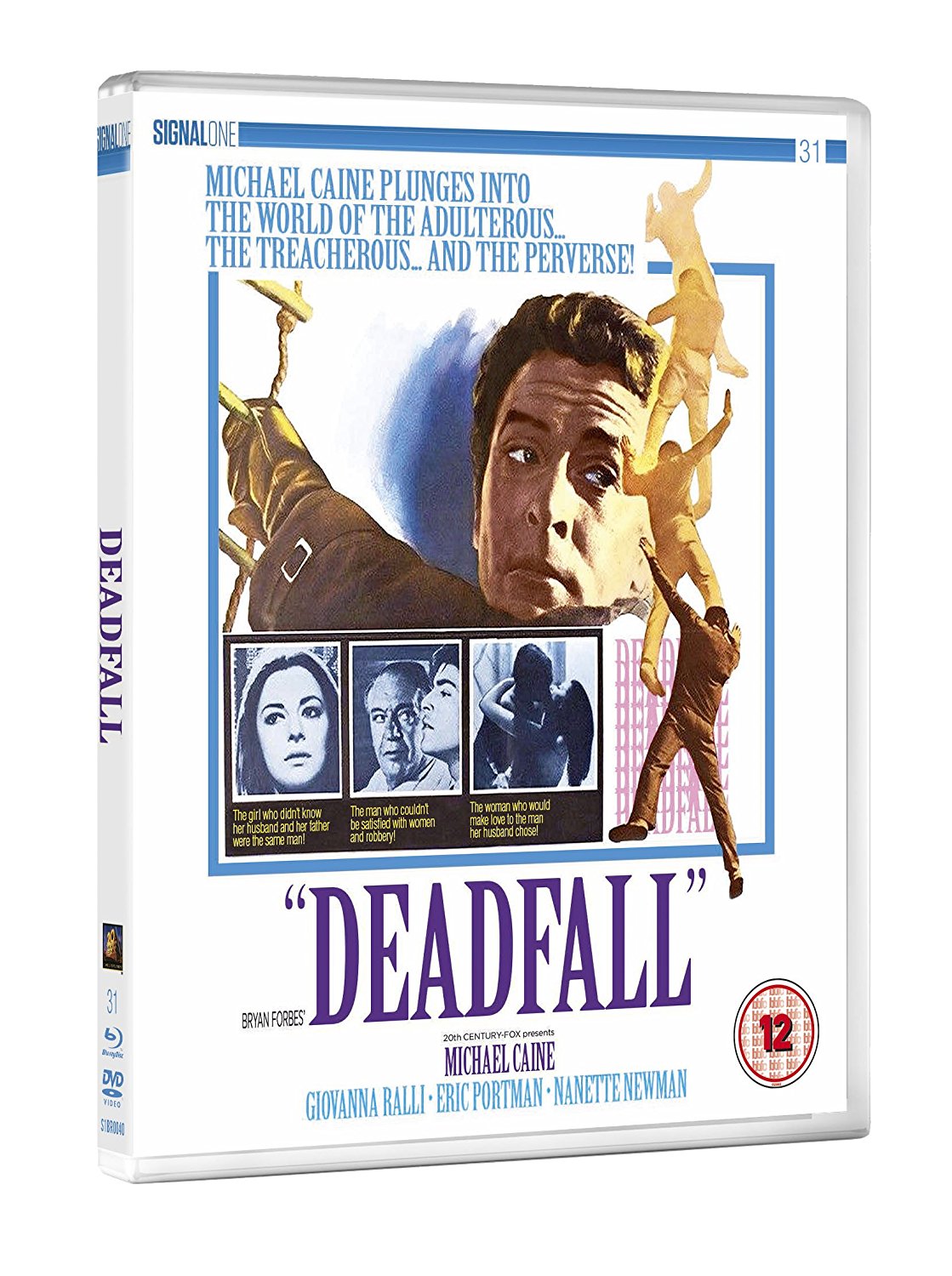

Deadfall (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th March 2018). |

|

The Film

Deadfall (Bryan Forbes, 1968) Deadfall (Bryan Forbes, 1968)

Henry Clarke (Michael Caine) is spending time at a private clinic in the Mediterranean, being treated for alcoholism. He is befriended by fellow patient Salinas (David Buck). Salinas tells Clarke that he was visited by the police: someone tried to rob one of his mansions the previous evening and was found dead on the beach below. Clarke, it is revealed, is a master thief, and he has managed to fake alcoholism in order to place himself in the clinic close to Salinas: Clarke, it seems, plans to rob Salinas, stealing his valuable collection of diamonds. Clarke is approached by Fé (Giovanna Ralli), who tells him that they are ‘birds of a feather’ and that she is aware of his profession: ‘You… take things’. Fé arranges a meeting between Clarke and Fé’s husband, Moreau (Eric Portman). Moreau proposes to Clarke that they team up to steal Salinas’ diamonds: Clarke has his skills as a thief, whereas the Moreau’s have the connections needed in order to ‘fence’ the stolen goods. The Moreaus suggest pooling their talents on the Salinas job. Clarke can steal the diamonds; the Moreaus will fence them. Clarke will received a third of the profits of this endeavour; the Moreaus will receive two thirds. Clarke investigates the Moreaus, speaking with Fillmore (Leonard Rossiter). Clarke agrees to ‘go in’ with the Moreaus, but is more interested in Fé than the diamonds. However, Moreau wants to commit another robbery before stealing from Salinas: this preliminary robbery will allow Moreau and Clarke to get to know one another and build mutual trust ‘It’s always a failure to jump into bed with somebody too quickly’, Moreau reminds Clarke.  The preliminary job, the robbery of a safe in the home of a musician, doesn’t go entirely as planned. Clarke and Moreau manage to gain entry into the building after scaling a dangerous outer wall, but Moreau is unable to crack the safe. Unwilling to return empty-handed, Clarke chops the safe out of the wall and carries it to the Moreaus’ car outside. This heist nets the group half a million dollars. Shortly afterwards, in Moreau’s library, Clarke finds a photograph of Moreau during the war, standing next to a Gestapo officer. The preliminary job, the robbery of a safe in the home of a musician, doesn’t go entirely as planned. Clarke and Moreau manage to gain entry into the building after scaling a dangerous outer wall, but Moreau is unable to crack the safe. Unwilling to return empty-handed, Clarke chops the safe out of the wall and carries it to the Moreaus’ car outside. This heist nets the group half a million dollars. Shortly afterwards, in Moreau’s library, Clarke finds a photograph of Moreau during the war, standing next to a Gestapo officer.

Fé is impressed with Clarke’s feat, and with Clarke himself, and though she professes her love for Clarke, she refuses to leave her husband. Fé and Clarke spend time together in Moreau’s coastal villa, whilst Moreau finds a handsome young male companion, Tony (Carlos Pierre). Moreau arranges a ball, during which Salinas is also to be in attendance. During the ball, Clarke plays matchmaker between Salinas and an attractive young woman (Nanette Newman). Clarke returns to the Moreau villa, where Moreau has deeper, more disturbing revelations in store for his new associate. These involve Moreau’s activities during the war and his relationship with Clarke. Antagonised by Moreau, Clarke is determined to take on the Salinas job solo, a task that is a thief’s equivalent of a suicide mission. Like many of Caine’s films during this period (and after, as a matter of fact), the theme of class divisions and inequality bubbles beneath the surface of this thriller. As in Sleuth (Joseph L Mankiewicz, 1972), The IPCRESS File (Sidney J Furie, 1966) or The Italian Job (Peter Collinson, 1969), the working-class Caine is pitted against more privileged characters in a conflict that is defined by inequality between the social classes. (It’s deeply ironic that Caine’s breakout role was as snooty, upper class officer Gonville Bromhead in Cy Endfield’s Zulu, 1964.) Caine is hired by the upper middle-class Moreau to steal diamonds from the home of the millionaire Salinas. In the film’s opening sequence, Clarke is found in a clinic where he is masquerading as an alcoholic in order to get close to Salinas, surveilling his planned victim: ‘An alcoholic is his own informant, so they say’, the clinic’s owner Dr Delgado (Vladek Sheybal) tells Clarke. Caine’s character demonstrates proletarian guile in playing one side off against the other, whilst also providing a more earthly object of desire for Moreau’s wife Fé, who is clearly dissatisfied in her marriage with the older Moreau – later revealed to be gay. ‘I don’t often find men attractive… as you know’, Fé reminds her husband early in the film; Giovanna Ralli’s performance in this picture is often criticised, but her delivery of the line is perfectly timed in its subtle insinuation of sexual frustration between Fé and her husband. Aside from her roles in westerns all’italiana such as Sergio Corbucci’s Il mercenario (A Professional Gun, 1968), Deadfall was one of several English-language films that featured Giovanna Ralli; the others include What Did You Do in the War, Daddy (1966) and The Caper of the Golden Bulls (also 1966).  The film depicts interpersonal relationships as a battleground fraught with hidden fault lines. ‘I’m her Cuba and she’s my Bay of Pigs’, Salinas tells Clarke when Clarke asks him about his wife. Moreau, for his part, is conflicted about his sexuality; the audience might assume that he is a stereotypically self-loathing ‘queer’ (as he’s referenced in the dialogue), but a couple of revelations that take place towards the end of the picture add further layers of complexity to the character. For his part, Moreau has an almost Nietzschean philosophy, communicated superbly via Eric Portman’s brilliantly-measured buttoned-up performance: ‘My dear, you don’t get what you want by understanding people’, he tells Fé, ‘You get what you want by willpower, mostly. And nothing weakens willpower so much as the effort to understand’. Later, he explains to Clarke his belief that jewel thieves are comparable with psychiatrists, ‘cutting away their [their patients’/victims’] neuroses painlessly’. Late in the film, discussing Moreau’s peccadilloes and the Salinas job, Moreau seems to conflate illicit sex and theft when he refers dryly to ‘adultery and other middle class sports’; it’s a line that, in retrospect, seems at the core of the film’s exploration of these themes. The film depicts interpersonal relationships as a battleground fraught with hidden fault lines. ‘I’m her Cuba and she’s my Bay of Pigs’, Salinas tells Clarke when Clarke asks him about his wife. Moreau, for his part, is conflicted about his sexuality; the audience might assume that he is a stereotypically self-loathing ‘queer’ (as he’s referenced in the dialogue), but a couple of revelations that take place towards the end of the picture add further layers of complexity to the character. For his part, Moreau has an almost Nietzschean philosophy, communicated superbly via Eric Portman’s brilliantly-measured buttoned-up performance: ‘My dear, you don’t get what you want by understanding people’, he tells Fé, ‘You get what you want by willpower, mostly. And nothing weakens willpower so much as the effort to understand’. Later, he explains to Clarke his belief that jewel thieves are comparable with psychiatrists, ‘cutting away their [their patients’/victims’] neuroses painlessly’. Late in the film, discussing Moreau’s peccadilloes and the Salinas job, Moreau seems to conflate illicit sex and theft when he refers dryly to ‘adultery and other middle class sports’; it’s a line that, in retrospect, seems at the core of the film’s exploration of these themes.

In the context of the Weinstein scandal, the scene in which Clarke, whilst still in the clinic, is urged by Salinas to have a massage has taken on slightly creepy undertones. The scene is intended to establish Clarke’s interest in the opposite sex; like many similar scenes in other films that starred Caine during the 1960, it’s intended to consolidate Caine’s character as a young man with an uncomplicated sexual appetite and an eye for attractive women, whilst also depicting Caine as possessing an earthy attractiveness for members of the opposite sex. Salinas urges Clarke to take the massage lying on his back, and the film cuts to a high-angle shot of the pretty masseuse rubbing oil into Caine’s chest. The film soon presents us with a point-of-view shot from Clarke’s perspective as he leers down the low-cut top of the masseuse at her ample breasts. Cut to a close-up of Caine expressing his pleasure with a close-mouthed grin. Revisiting the film in the immediate aftermath of the Weinstein scandal and its cultural fallout via the #metoo campaign, the connotations of this scene become very different to what was originally intended but nevertheless in line with the film’s reflection on sex, theft, excitement and shame.  For his part, in comparison with Moreau, Clarke sees his work as a thief much more romantically, suggesting the interest in jewel thieves is sourced from the Robin Hood legend: ‘stealing from the rich to give to the poor and all that’. For Clarke, the challenge of a heist is perhaps its own reward. ‘Why the obsession?’, Moreau asks Clarke when Clarke suggests they should bypass the preliminary heist and move straight on to robbing Salinas. ‘Why not?’, Clarke respond, adding ‘Why climb Everest?’ ‘Because it’s there’, Moreau admits. Salinas’ mansion is a challenge because Salinas enjoys the chase too, Clarke reasons. ‘There’s always something faintly ludicrous, don’t you think, about two grown men talking blandly about a robbery’, Moreau observes, reflecting on the absurdity of the profession he and Clarke share. ‘It’s a game’, Clarke notes, ‘Salinas enjoys it too, the counterplotting. All the fun isn’t on our side’. For his part, in comparison with Moreau, Clarke sees his work as a thief much more romantically, suggesting the interest in jewel thieves is sourced from the Robin Hood legend: ‘stealing from the rich to give to the poor and all that’. For Clarke, the challenge of a heist is perhaps its own reward. ‘Why the obsession?’, Moreau asks Clarke when Clarke suggests they should bypass the preliminary heist and move straight on to robbing Salinas. ‘Why not?’, Clarke respond, adding ‘Why climb Everest?’ ‘Because it’s there’, Moreau admits. Salinas’ mansion is a challenge because Salinas enjoys the chase too, Clarke reasons. ‘There’s always something faintly ludicrous, don’t you think, about two grown men talking blandly about a robbery’, Moreau observes, reflecting on the absurdity of the profession he and Clarke share. ‘It’s a game’, Clarke notes, ‘Salinas enjoys it too, the counterplotting. All the fun isn’t on our side’.

As with numerous late-1960s heist films (Giuliano Montaldo’s 1967 Grand Slam; Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le cercle rouge, 1970), the two heists performed by Clarke in Deadfall seem motivated by the desire to outdo the benchmark of many heist films of the period, Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955). (Rififi’s pivotal heist sequence is arguably still the benchmark for this subgenre.) However, few if any 1960s heist pictures achieved anything equal to Rififi; Deadfall is no exception. The preliminary robbery that Moreau gets Clarke to perform before they move on to the big fish, Salinas, cuts between the heist and a concert, for which John Barry wrote an original piece of music and in which Barry appeared in a cameo as the conductor. Barry’s main title theme for the picture, ‘My Love Has Two Faces’, is sung by Shirley Bassey and is strongly reminiscent of Barry’s songs for the James Bond films. Michael Caine later commented that ‘When the film came out […] people talked more about the music than the film [….] [Barry] never did any duff music, even for a duff movie. ‘Cause Deadfall was a duff movie – with great music in it. I think the LP made more money than the picture’ (Caine, quoted in Fiegel, 2012: np).

Video

Taking up 19.9Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Deadfall is uncut, with a running time of 119:50 mins. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Taking up 19.9Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Deadfall is uncut, with a running time of 119:50 mins. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

The film was shot in colour on 35mm stock. The original photography makes effective use of telephoto lenses, flattening perspective and using them to frame the characters within and behind objects in the foreground, offering a strong visual theme of surveillance that underscores the paranoia of the narrative. Alongside this, some of the interiors are shot using wide-angle lenses with great depth of field, allowing strong staging-in-depth. The film also makes copious use of canted angles to suggest a world out of balance. The source of this presentation isn’t identified in the materials. However, a very pleasing level of fine detail is present throughout the film, especially in closeups, though some of these seem contain evidence of very slight digital edge enhancement/sharpening – certainly nothing damaging or distracting, but edges look a smidgen too pronounced for a 35mm picture at times. The image has a strong sense of depth to it, especially in the interior scenes that use short focal lengths and feature staging-in-depth. Contrast levels are very good too, with midtones having a strong sense of definition. Some shadow detail in the low light scenes seems a little flat though not ‘crushed’ per se. Highlights are even and balanced. Colours are consistent and naturalistic, and the palette is naturalistic. Finally, the presentation is carried by a robust encode which retains the structure of 35mm film. Overall, it’s a very satisfying, film-like presentation.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 1.0 track. This is clean and clear throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and fairly accurate, though there are a couple of anomalies that suggest they were compiled by an American English speaker or software: eg, when Caine says ‘lieutenant’, the subtitles translate this into ‘leftenant’; when Caine talks about having a paper round as a young man, the subtitles translate this into ‘paper route’.

Extras

The disc includes the following: The disc includes the following:

- Isolated Score (in LPCM 2.0). Foregrounding John Barry’s excellent score, this track offers an alternative way to view the film and is actually an isolated music and effects track. - ‘The John Barry Touch: The Music of a Master’ (19:04). John Barry, Bryan Forbes and writer Eddi Fiegel talk about Barry’s music, focusing on his work for Deadfall and discuss the position of this film within Barry’s career as a whole. This is a featurette which previously appeared on the 2006 Fox DVD release of Deadfall. - ‘From the Page to the screen: An Interview with Film Expert Chris Poggiali’ (21:34). In a new interview, Poggiali discusses Deadfall, situating it within the films that Caine made during the 1960s. Poggiali talks about Deadfall as an outgrowth of the two picture contract that Caine signed with Fox, resulting in this picture and Guy Green’s The Magus (1968, released on Blu-ray by Signal One recently and reviewed by us here). The Desmond Cory novel on which the film was based was compared with Ian Fleming’s James Bond books, and this film adaptation was compared with the Bond films of the 1960s – resulting in the filmmakers hiring John Barry to score the picture. Poggiali talks about the writing of the film: Robert Towne was the film’s original screenwriter, and Poggiali teases out the similarities between Towne’s script for Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) and the narrative of Deadfall. - Still Gallery (36 images). - Trailer (2:29). The case also includes a booklet containing a new piece about the film by film critic Christopher Bray.

Overall

Deadfall is in many ways a minor diversion: a film about thieves with a travelogue quality, featuring glossy colour photography of some attractive locales. Despite its fairly heavy reliance on clichés of the heist picture, Deadfall has many noticeable charms. Portman’s performance is excellent throughout, and Caine’s characteristic cool insouciance is bolstered by some dry dialogue: ‘They say that’s the nicest death’, Clarke tells Salinas when Salinas informs him that the man who tried to rob his mansion was found drowned on the beach. ‘Who?’, Salinas asks, ‘Who says that?’ ‘People who haven’t been drowned’, Clarke asserts matter-of-factly. Elsewhere, Clarke shares a train carriage with Fé. Clarke manages to fall asleep. He wakes up sleepily. Fé is still awake. ‘Are you a bad sleeper on trains?’, he asks her. ‘I am just a bad sleeper’, she responds. ‘Well, that’s a point in your favour’, Clarke tells her, ‘Women who sleep easily are usually bitches’. The picture builds towards an unconventional and rather bold denouement that is anticipated in Clarke’s first meeting with Fé, during which he tells her ‘I’m fairly shockproof. I can be dropped from a height without much damage’. In all, it’s a fun film, though perhaps a little overlong; the narrative could be leaner, tighter, and more closely plotted. More could have been done with the revelations Moreau presents towards the end of the film: these could have been dripped into the narrative earlier, generating a greater sense of tension between the trio. A little more use could have been made of Fillmore, Leonard Rossiter’s memorable turn as a stiff-upper-lip Brit who tells Clarke about the Moreaus. Deadfall is in many ways a minor diversion: a film about thieves with a travelogue quality, featuring glossy colour photography of some attractive locales. Despite its fairly heavy reliance on clichés of the heist picture, Deadfall has many noticeable charms. Portman’s performance is excellent throughout, and Caine’s characteristic cool insouciance is bolstered by some dry dialogue: ‘They say that’s the nicest death’, Clarke tells Salinas when Salinas informs him that the man who tried to rob his mansion was found drowned on the beach. ‘Who?’, Salinas asks, ‘Who says that?’ ‘People who haven’t been drowned’, Clarke asserts matter-of-factly. Elsewhere, Clarke shares a train carriage with Fé. Clarke manages to fall asleep. He wakes up sleepily. Fé is still awake. ‘Are you a bad sleeper on trains?’, he asks her. ‘I am just a bad sleeper’, she responds. ‘Well, that’s a point in your favour’, Clarke tells her, ‘Women who sleep easily are usually bitches’. The picture builds towards an unconventional and rather bold denouement that is anticipated in Clarke’s first meeting with Fé, during which he tells her ‘I’m fairly shockproof. I can be dropped from a height without much damage’. In all, it’s a fun film, though perhaps a little overlong; the narrative could be leaner, tighter, and more closely plotted. More could have been done with the revelations Moreau presents towards the end of the film: these could have been dripped into the narrative earlier, generating a greater sense of tension between the trio. A little more use could have been made of Fillmore, Leonard Rossiter’s memorable turn as a stiff-upper-lip Brit who tells Clarke about the Moreaus.

Signal One’s Blu-ray presentation of Deadfall contains a pleasingly filmlike presentation of the main feature and supports this with some good extra material. It’s a solid release of an a film that is often unfairly maligned (not least by its own star, Michael Caine, who has spoken rather disparagingly about the film in interviews). It’s not the best of the 1960s heist pictures, but it’s an entertaining film with some interesting thematic content, excellent photography and great John Barry music. References: Fiegel, Eddi, 2012: John Barry: A Sixties Theme – From James Bond to ‘Midnight Cowboy’. London: Faber & Faber Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|