|

|

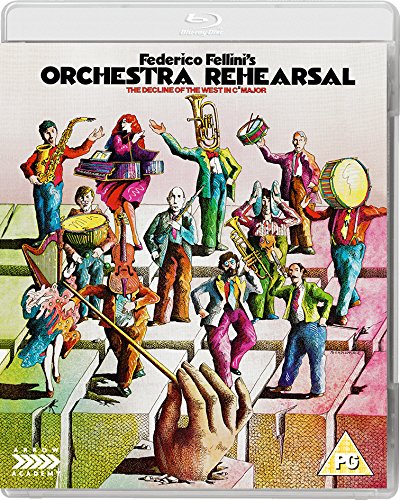

Orchestra Rehearsal AKA Prova d'orchestra (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th March 2018). |

|

The Film

Prova d’orchestra (Orchestra Rehearsal; Federico Fellini, 1978) Prova d’orchestra (Orchestra Rehearsal; Federico Fellini, 1978)

In an ancient church oratory, an orchestra gathers for a rehearsal. The rehearsal is filmed by a television documentary crew. The copyist, musicians and conductor are interviewed about their work. Each section of the orchestra emphasises its importance over the others. Some members of the orchestra are unhappy about being filmed; the rehearsal is presided over by the muscians’ union representative, who intervenes in order to remind the musicians of their negotiated rights. Tension is evident between the musicians and the conductor, who has high expectations and criticises the musicians incessantly. Some musicians believe that the conductor is little more than a glorified metronome, and they assert that the orchestra would function just as well – perhaps even better – with a mechanical device at its helm. After a union-stipulated 20 minute break, the musicians return to the auditorium and refuse to rehearse for the conductor. Fights break out; slogans are chanted and written in graffiti on the walls of the ancient church. Artwork and tombs are vandalised. The protest threatens to erupt into a riot, but is halted when a wrecking ball smashes through one of the church’s walls. The conductor manages to wrest control and the orchestra resumes its rehearsal. The music is beautiful, but the conductor is still not satisfied, and he angrily berates the musicians, eventually segueing into German. As the screen fades to black, the angry, impassioned voice of the conductor can be heard; it seems near-identical to the voice of Hitler.  Made after Federico Fellini’s expansive Casanova (1976), Orchestra Rehearsal was the opposite of that production: a relatively small-scale story that mostly takes place in a single location, in a modern-day setting, and completed in just 16 days. Orchestra Rehearsal is presented in pseudo-documentary style. The camera is acknowledged and addressed directly by the orchestra’s participants, who are taking part in a television documentary about the orchestra rehearsal. (I once played in a youth orchestra whose rehearsal was documented by the cameras of the BBC’s well-loved children’s programme Blue Peter, so despite its outward absurdity the set-up is utterly recognisable to me.) The film was made for Italian television network RAI but eventually found a cinema release. Made after Federico Fellini’s expansive Casanova (1976), Orchestra Rehearsal was the opposite of that production: a relatively small-scale story that mostly takes place in a single location, in a modern-day setting, and completed in just 16 days. Orchestra Rehearsal is presented in pseudo-documentary style. The camera is acknowledged and addressed directly by the orchestra’s participants, who are taking part in a television documentary about the orchestra rehearsal. (I once played in a youth orchestra whose rehearsal was documented by the cameras of the BBC’s well-loved children’s programme Blue Peter, so despite its outward absurdity the set-up is utterly recognisable to me.) The film was made for Italian television network RAI but eventually found a cinema release.

Unusually for a Fellini picture, Orchestra Rehearsal is openly political, satirical and symbolic. The church, built in the thirteenth century, represents the past: it contains the tombs of three popes and seven bishops, the copyist tells us; ‘This place is full of dead people’. The different sections of the orchestra, each convinced of their own worth and importance, represent different strata within society; the conductor is the political class, managing to unite the musicians against a mutual threat only to turn into a fascistic dictator. The film, reputedly inspired by the abduction and murder of Prime Minister Aldo Moro by Brigate Rosso members in 1978, is heavily critical of the impact of the trade unions: some of the musicians are so concerned with their negotiated rights that this prevents the rehearsal from being completed. One of the violinists refuses to play the same piece of music more than twice, as this is the number of times stipulated by his union rep. ‘If I were you, I’d think less about your union and more about the music’, the conductor tells the musicians in response to this assertion. When music/art becomes ‘polluted’ by capital and issues of labour (and labour management), Fellini seems to be saying, the production of art becomes impossible: it loses its spontaneity, freedom and inherent creativity. (‘This is like a factory’, the conductor says in reference to the rehearsal, or at least it should be where we try to make something’.) These disputes become divisive; when an orchestra is divided, it cannot achieve harmony. The instruments should complement one another, but each section in the orchestra becomes obsessed with ‘proving’ its value over the other sections. The natural outcome of all of this, the film argues, is violence, and in the aftermath of this violence a dictator emerges. It’s a bleak and, for all its outward humour, quite angrily political film; it is certainly a very unconventional Fellini picture.  The conductor is an interesting character. He chastises the musicians for their sloppy playing, and in his private room he addresses the camera in interview. Here, he displays what seems to be a genuine love of music, but a profound frustration with the musicians who are necessary to its production. He reflects on the breakdown in trust between conductors and musicians. ‘There is only mistrust between me and my musicians’, he says, ‘We are all against each other. Our wariness undermines our trust. Then there is contempt, resentment and anger for something that has gone and will never come back’. He concludes that ‘That’s how we play together. United only by hatred. Like a broken family’. He argues that he must behave like a sergeant-major who ‘kicks everyone in the arse’ but that his hands have been tied by union-initiated legislation. This has resulted in it being impossible to conduct an orchestra effectively. After the wrecking ball breaks through the church wall, the conductor seizes the chance to unite the orchestra. The musicians quietened by this dramatic event, the conductor finds it easy to draw their attention. He conducts them in one last go-round for the piece being rehearsed, and the rehearsal seems to be a success: the musicians are in time and harmonic. However, the conductor seems to recognise the power that he now holds, and he once again returns to berating the musicians, criticising them indignantly. The conductor is an interesting character. He chastises the musicians for their sloppy playing, and in his private room he addresses the camera in interview. Here, he displays what seems to be a genuine love of music, but a profound frustration with the musicians who are necessary to its production. He reflects on the breakdown in trust between conductors and musicians. ‘There is only mistrust between me and my musicians’, he says, ‘We are all against each other. Our wariness undermines our trust. Then there is contempt, resentment and anger for something that has gone and will never come back’. He concludes that ‘That’s how we play together. United only by hatred. Like a broken family’. He argues that he must behave like a sergeant-major who ‘kicks everyone in the arse’ but that his hands have been tied by union-initiated legislation. This has resulted in it being impossible to conduct an orchestra effectively. After the wrecking ball breaks through the church wall, the conductor seizes the chance to unite the orchestra. The musicians quietened by this dramatic event, the conductor finds it easy to draw their attention. He conducts them in one last go-round for the piece being rehearsed, and the rehearsal seems to be a success: the musicians are in time and harmonic. However, the conductor seems to recognise the power that he now holds, and he once again returns to berating the musicians, criticising them indignantly.

The sense of division within the ranks is represented through the film’s use of language, the different sections of the orchestra being associated with various regional dialects of Italian. This is something which doesn’t ‘carry’ well in the English subtitled version on this release, or in the dubbed versions that have circulated previously.

Video

The film takes up 16.7Gb of space on the Bu-ray disc and runs for 72:14 mins. Presented in the 1.78:1 screen ratio, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The aspect ratio seems natural; compositions seem to work well in this ratio. It’s a very pleasing presentation of the film, shot on 35mm colour stock. The source contains no heavy damage other than some fluctuations in the density of the emulsions, and an excellent level of fine detail is present throughout. Contrast levels are pleasing throughout, with midtones being characterised by a strong sense of definition, blacks being satisfyingly deep and highlights being even and balanced. No evidence of harmful digital tinkering is present, and a solid encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

The film is presented in Italian, via a LPCM 2.0 track which is accompanied by optional English subtitles. The track is clear and problem-free and demonstrates good range, the music being carried cleanly and clearly; though as noted above, some of the nuances (in terms of having the actors in each section speak with different regional accents) are most likely lost on viewers who don’t speak Italian.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Richard Dyer on Nino Rota and Orchestra Rehearsal’ (20:43). In a new interview, Dyer talks about Rota’s working relationship with Fellini, which began with The White Sheik and ended with Orchestra Rehearsal. Orchestra Rehearsal was a rare exception in Rota’s career, as it was one of the few films (perhaps the only) on which Rota wrote the score before the film went into production and during which Rota was on set. (For most films scored by Rota, Rota was drafted in after production to write the music.) - ‘Orchestrating Discord’ (23:10). Fellini biographer John Baxter narrates a new video essay looking at Orchestra Rehearsal. Baxter discusses Fellini’s approach, ‘danc[ing] into the act of creation’. Baxter situates the film within Fellini’s career, reflecting on its relationship with Casanova, the earlier film being plagued by strikes and the infamous manner in which that film’s negative was ‘abducted’ and held ransom in a robbery of the Technicolor labs of Tiburtino. Fellini had a strong dislike of television but agreed to make Orchestra Rehearsal when RAI offered him carte blanche to make the picture ‘as controversial as he liked’. - ‘Felliniana Collection’ (30 images). This feature contains rare printed materials relating to the film – posters, lobby cards and pressbooks, etc, sourced from Texan collector’s Don Young’s huge collection of Fellini-related materials.

Overall

By the end of the picture, it’s obvious that the church represents an Italy that has been paralysed by trade unions and workers’ strikes, and under constant threat from terrorism. These are the conditions, Fellini seems to suggest, from which a dictator could emerge and seize control. The proletarian musicians seek respect for their craft, reminding the viewer that ‘Most musicians come from the provinces’ and ‘have a very modest academic background’. Music becomes less an art capable of uplifting the spirit and is seen as just another link in the chain of exploitation and inequality. ‘Music should be a public good’, one of the characters notes, ‘Instead it’s used to exploit us’. The film is startling, all the more so for the clever integration of Nino Rota’s score. Musicians may be frustrated by the lack of concern seemingly given to training the actors to mimic the work of real musicians: the violinists’ bow movements are all over the shop, for example. By the end of the picture, it’s obvious that the church represents an Italy that has been paralysed by trade unions and workers’ strikes, and under constant threat from terrorism. These are the conditions, Fellini seems to suggest, from which a dictator could emerge and seize control. The proletarian musicians seek respect for their craft, reminding the viewer that ‘Most musicians come from the provinces’ and ‘have a very modest academic background’. Music becomes less an art capable of uplifting the spirit and is seen as just another link in the chain of exploitation and inequality. ‘Music should be a public good’, one of the characters notes, ‘Instead it’s used to exploit us’. The film is startling, all the more so for the clever integration of Nino Rota’s score. Musicians may be frustrated by the lack of concern seemingly given to training the actors to mimic the work of real musicians: the violinists’ bow movements are all over the shop, for example.

It’s certainly an unconventional Fellini picture, the antithesis of much of Fellini’s other work and standing in stark relief against Fellini’s previous picture, Casanova. Fellini fans might find this picture slightly alienating, but it’s an interesting film – especially when one considers its relationship with its social context. Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Orchestra Rehearsal is solid and satisfyingly film-like, and is supported by some good contextual material. Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|