|

|

After the Storm AKA Umi yori mo mada fukaku (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th March 2018). |

|

The Film

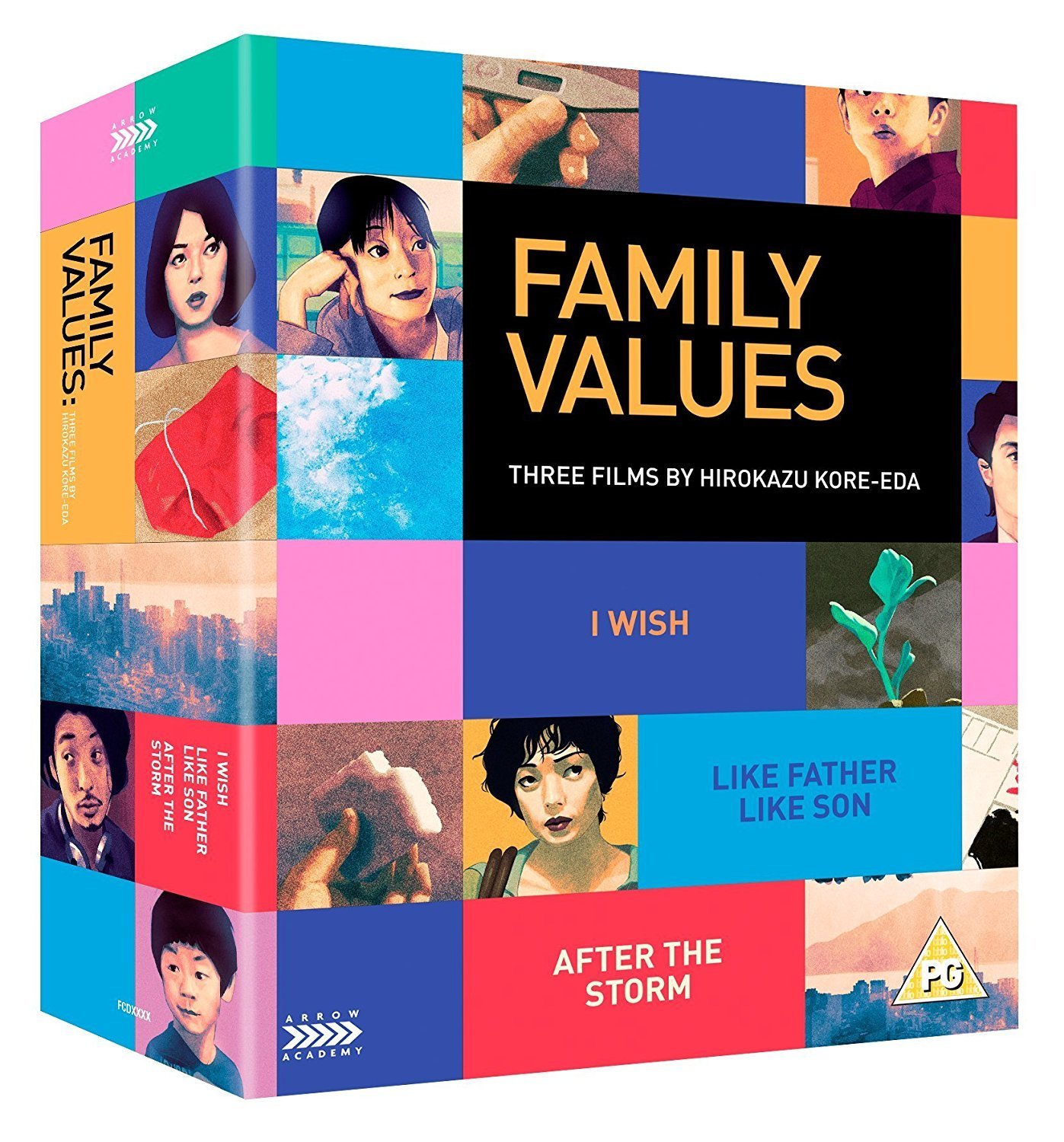

Family Values: Three Films by Hirokazu Kore-eda  I Wish (2011): In a divided family, brothers Koichi and Ryunosuke are forced apart. Koichi (Maeda Kohki) lives with the boys’ mother and her parents near the volcano Sakurajima, whilst the younger Ryunosuke (Maeda Ohshiro) lives in Fukuoka with their father. The brothers keep in touch via telephone. Koichi dreams of the volcano erupting, forcing his mother and her family to relocate and necessitating a reunion between the boys’ estranged parents. I Wish (2011): In a divided family, brothers Koichi and Ryunosuke are forced apart. Koichi (Maeda Kohki) lives with the boys’ mother and her parents near the volcano Sakurajima, whilst the younger Ryunosuke (Maeda Ohshiro) lives in Fukuoka with their father. The brothers keep in touch via telephone. Koichi dreams of the volcano erupting, forcing his mother and her family to relocate and necessitating a reunion between the boys’ estranged parents.

When news that the bullet train is due to arrive at Sakurajima, Koichi becomes aware that at a spot nearby, reachable by train, two bullet trains will pass one another. This is apparently a rare occurrence, and both Koichi and Ryunosuke, and their respective friends, become obsessed by the legend that if one sees the intersection of two bullet trains and makes a wish at the precise time the trains pass one another, that wish will be granted. The brothers make plans to visit this location with their friends, Koichi in particular planning to wish for a reunion between his mother and father. To achieve this, the boys must show guile, earning the money for their train fare by selling their possessions and enlisting the help of sympathetic grown-ups to bunk off from school.  Like Father, Like Son (2013): Ryota (Fukuyama Masaharu) and Midori (Ono Machiko), the parents of six year old Nonomiya Keita (Nonomiya Keita), push their son’s talents, Ryota seemingly intent on moulding his son via the same experiences Ryota had as a child – studying at the same elite school; playing the piano. Ryota expresses dissatisfaction with his son’s lack of drive and ambition. When Ryota and Midori are approached by the hospital where Midori gave birth, they discover that owing to a deliberate mix-up engineered by an embittered nurse, their baby was swapped with another belonging to the proletarian Saki family. Like Father, Like Son (2013): Ryota (Fukuyama Masaharu) and Midori (Ono Machiko), the parents of six year old Nonomiya Keita (Nonomiya Keita), push their son’s talents, Ryota seemingly intent on moulding his son via the same experiences Ryota had as a child – studying at the same elite school; playing the piano. Ryota expresses dissatisfaction with his son’s lack of drive and ambition. When Ryota and Midori are approached by the hospital where Midori gave birth, they discover that owing to a deliberate mix-up engineered by an embittered nurse, their baby was swapped with another belonging to the proletarian Saki family.

The patriarch of the Saki family, Yudai (Lily Franky), owns and manages an appliance repair shop. Together with his wife, Yukari (Maki Yoko), Yudai is the opposite of Ryota, unafraid of being seen as childish in his play with his children. His son Ryusei (Hwang Shogen) is a more outgoing child than Keita. Ryota takes an almost instant dislike to Yudai, and he and his wife are faced with the decision as to whether they seek to build a relationship with Ryusei or continue to accept Keita as their son – regardless of his biological heritage. The Nonomiya and Saki families eventually decide to allow their sons to spend time with the other family, in the hope of eventually ‘swapping’ children. However, Ryota speaks quietly with his lawyers, believing that he and Midori might be able to take control of both boys – thus ensuring they can build a relationship with Ryusei in their life of privilege whilst also retaining parental rights over Keita. Midori is torn and broken by Ryota’s belief that they can abandon the six years they have spent with Keita in favour of the blood connection they have to Ryusei. Midori also expresses the belief that she feels as if she is betraying Keita by loving Ryusei. The disparate families of Keita and Ryusei are drawn together by their experiences, in the process learning from one another.  After the Storm (2016): As a typhoon approaches, Shinoda Ryota (Abe Hiroshi) drifts home to visit his elderly mother. Ryota’s father, an inveterate gambler, has passed away recently. Ryota plans to pawn his father’s possessions in order to pay off his own gambling debts and also to pay the child support he owes to his ex-wife Kyoko (Maki Yoko) for the care of his son Shingo (Yoshizawa Taiyo). After the Storm (2016): As a typhoon approaches, Shinoda Ryota (Abe Hiroshi) drifts home to visit his elderly mother. Ryota’s father, an inveterate gambler, has passed away recently. Ryota plans to pawn his father’s possessions in order to pay off his own gambling debts and also to pay the child support he owes to his ex-wife Kyoko (Maki Yoko) for the care of his son Shingo (Yoshizawa Taiyo).

As a younger man, Ryota wrote a critically acclaimed novel, The Empty Table. Nowadays, however, he works as a private investigator, mostly involved in messy divorce cases. Ryota claims that he has taken on this work as research for a new novel, though in truth it has become a ‘survival’ job; nevertheless, Ryota has been approached with a new writing job scribing a manga about a gambling addict. Ryota refuses, perhaps owing to a sense that writing a manga is beneath him, or perhaps because the subject matter is too close to home. Ryota owes his ex-wife a heavy amount of child support, and to make matters worse she has a new lover who insists that it’s unwise for Shingo to spend time with either Ryota or his mother. Ryota tries to cover his child support debt through various schemes, including shaking down a youth who Ryota’s boss later reveals to be the son of a police detective. Ryota spends the day with Shingo, taking the boy to buy some new baseball cleats and then visiting Ryota’s mother. As the typhoon nears, Ryota and Shingo must spend the night in the apartment of Ryota’s mother. They are joined by Kyoto, who hopes to take Shingo home but becomes trapped by the storm. Will the proximity effect a reconciliation between Ryota and Kyoto?  Analysis: Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career working on documentaries, and his feature films have a very documentary-like quality to them, offering simple, naturalistic stories about issues facing modern families – most often, the relationships between parents and their children. The narratives of these films frequently focus on a point of reunion between family members who have, for whatever reasons, become alienated from one another. The films’ humanism and focus on families and family-related issues have led, perhaps inevitably, to Kore-eda being compared with Ozu, though in interviews Kore-eda often gently rejects this comparison. Kore-eda often suggests he is closer in spirit to Naruse Mikio, with the proletarian focus of Mikio’s shomin-geki pictures, or even the social realism of Ken Loach (see Bradshaw, 2015: np). Analysis: Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career working on documentaries, and his feature films have a very documentary-like quality to them, offering simple, naturalistic stories about issues facing modern families – most often, the relationships between parents and their children. The narratives of these films frequently focus on a point of reunion between family members who have, for whatever reasons, become alienated from one another. The films’ humanism and focus on families and family-related issues have led, perhaps inevitably, to Kore-eda being compared with Ozu, though in interviews Kore-eda often gently rejects this comparison. Kore-eda often suggests he is closer in spirit to Naruse Mikio, with the proletarian focus of Mikio’s shomin-geki pictures, or even the social realism of Ken Loach (see Bradshaw, 2015: np).

I Wish offers a view of a broken family from the perspective of the two children, brothers who are emotionally inseparable and love each other dearly but who are separated physically by the animosity that exists between their parents. They become concerned that they will grow apart, after one of Ryunosuke’s friends tells him ‘Even family will forget you if they don’t see you’. In many ways, the two young boys, who strive to pull their family back together, are more mature in their outlook than their parents: their mother separated from their father owing to his perceived lack of ambition (he’s a jobbing musician), and their father drifts from job to job and lives like a teenager (‘We have two children. You still behave like a student’, the boys’ mother tells their father in a flashback). The original Japanese title for I Wish, ‘Kiseki’, translates more closely into English as ‘Miracle’. The miracle in the film is the one wished for by the two brothers: a reunion between their father and mother which will result in Koichi and Ryunosuke once again living together, sharing their adventures and their childhood. (Ryunosuke tells his friends that he and Koichi are ‘connected by a thread you can’t see’.) The boys believe this miracle will be granted if they visit the site where two bullet trains will pass one another and make a wish: if they make a wish at the precise moment that the paths of the two trains intersect, this wish will come true. To this end, both Koichi and Ryunosuke employ the efforts of their friends to help them reach a spot overlooking the tracks where the bullet trains will pass, the two groups of children making what is essentially a pilgrimage to a spot where they believe miracles will be granted.  Making this journey requires the children to bunk off school, deceiving some adults and seeking the assistance of others. Koichi is aided in his quest by his grandfather, who has been quietly distant for much of the film though clearly respects and admires Koichi; Koichi’s grandfather agrees to help Koichi avoid school on the day of the ‘miracle’ by turning up at the school and validating the excuse concocted by Koichi and his friends that they have picked up a virus and must be excused from the rest of the day’s classes. Koichi’s friends are also assisted by the school nurse who, after the boys have all fainted (unconvincingly) in tandem during one of their classes, shows them how to fake a high temperature by warming up the thermometer. Making this journey requires the children to bunk off school, deceiving some adults and seeking the assistance of others. Koichi is aided in his quest by his grandfather, who has been quietly distant for much of the film though clearly respects and admires Koichi; Koichi’s grandfather agrees to help Koichi avoid school on the day of the ‘miracle’ by turning up at the school and validating the excuse concocted by Koichi and his friends that they have picked up a virus and must be excused from the rest of the day’s classes. Koichi’s friends are also assisted by the school nurse who, after the boys have all fainted (unconvincingly) in tandem during one of their classes, shows them how to fake a high temperature by warming up the thermometer.

However, at the site of the ‘miracle’, Koichi and Ryunosuke come to an acceptance about the way their family has been split up, and neither of them make the expected wish for a family reunion. As Adam Bingham has suggested, the film’s resolution turns I Wish into ‘a story about growth and maturation, of discarding unrealistic dreams and desires not only as an intrinsic part of growing up but also of being a member of a family, an institution that does not exist as an ideal but which is not therefore to be negated or destroyed’ (Bingham, 2015: np). The characters are sketched with a deft economy, including Koichi’s male schoolteacher who seems initially unsympathetic towards Koichi, to the point that some of the other children suggest complaining, but pulls Koichi aside and quietly tells the boy that he (the teacher) grew up without a father too, encouraging Koichi to ‘Hang in there’ and offering the child support if he needs it. Their father is a rounded character too, his behaviour seemingly validating the boys’ mother’s complaint that he has no ambition. The father is focused on his music and is shown having fun with his friends and bandmates, behaving like an overgrown teenager. However, he has a valuable lesson for Ryunosuke, reminding the boy that ‘There’s enough room in this world for wasteful things. Imagine if everything had meaning. You’d choke’. Nevertheless, the father wishes for his boys not to follow his example: ‘I want you to grow up to be someone who cares about more than your own life’, he tells Ryunosuke. Later, when the boys’ mother expresses to Ryunosuke (via a telephone call) a regret over the fact that she hasn’t spoken to him in a while, Ryunosuke responds by saying, quite innocently, ‘You think I’m just like dad, and I thought that’s why you didn’t want to see me’.  The relationships between fathers and sons, and the nature/nurture debate, is at the core of the next film in this set, Like Father, Like Son. Ryota is a distant father to his six year old son Keita, spending his days and nights working and hoping to buy his son’s education via Keita’s entry into the same elite school where Ryota studied. Ryota struggles to comprehend his son’s outlook on life. As the film opens, we see Ryota and Midori in an interview at the school they hope Keita will attend; when asked if Keita has any weaknesses, Ryota responds by stating that Keita ‘doesn’t seem to mind losing’, adding with a pause that ‘As his father, it’s a little dissatisfying’. The relationships between fathers and sons, and the nature/nurture debate, is at the core of the next film in this set, Like Father, Like Son. Ryota is a distant father to his six year old son Keita, spending his days and nights working and hoping to buy his son’s education via Keita’s entry into the same elite school where Ryota studied. Ryota struggles to comprehend his son’s outlook on life. As the film opens, we see Ryota and Midori in an interview at the school they hope Keita will attend; when asked if Keita has any weaknesses, Ryota responds by stating that Keita ‘doesn’t seem to mind losing’, adding with a pause that ‘As his father, it’s a little dissatisfying’.

Are children completely what their parents make them or is there a genetic component to their behaviour? Is personality a product of nurture or nature? Keita’s parents push him to learn the piano, and Ryota seems to have displayed a prodigious musical talent as a child; but despite constant practising, Keita seems unable to progress beyond the basics. His parents enter him for a recital where Keita plays competently but is easily outshined by the other children. The film contrasts the leisure activities of Keita and Ryusei. Both boys enjoy video games, though Keita has been exposed to the social pleasures of the Nintendo Wii and Ryusei is more interested in solitary handheld games (principally, what seems to be a vintage early/mid 1980s Donkey Kong game). However, as Keita spends time with the Sakis, he demonstrates an increasing admiration for Yudai, who he describes as ‘great. He can fix anything’. Ryota’s response when his son, or Ryusei, comes to him with a broken toy is the suggestion that it should be discarded and a new one bought, whereas Yudai demonstrates ingenuity and know-how in repairing the toys of his children.  Like Father, Like Son juxtaposes the ‘haves’ (Keita’s family) with the ‘have nots’ (the family of Ryusei), ultimately suggesting that the latter have greater riches beyond material goods – a tight-knit family unit, parents who are present in their children’s lives. ‘Your husband sure likes to work’, Yudai tells Midori, ‘My motto is, “Put off till tomorrow whatever you can”’. Later, Yudai advises Ryota that ‘You should make more time to be with your child [….] No one can take your place as your son’s father’. When Ryota suggests that he and Midori can give a substantial sum of money to the Sakis in exchange for ‘ownership’ of both Keita and Ryusei, Yudai responds with disgust: ‘You’re trying to buy a child with money?’, he asserts angrily, ‘You never lost at anything. You can’t understand how other people feel’. Privilege is contrasted with its opposite; however, Like Father, Like Son avoids becoming a didactic tract and represents both Keita and Ryusei as happy in their own ways. Like Father, Like Son juxtaposes the ‘haves’ (Keita’s family) with the ‘have nots’ (the family of Ryusei), ultimately suggesting that the latter have greater riches beyond material goods – a tight-knit family unit, parents who are present in their children’s lives. ‘Your husband sure likes to work’, Yudai tells Midori, ‘My motto is, “Put off till tomorrow whatever you can”’. Later, Yudai advises Ryota that ‘You should make more time to be with your child [….] No one can take your place as your son’s father’. When Ryota suggests that he and Midori can give a substantial sum of money to the Sakis in exchange for ‘ownership’ of both Keita and Ryusei, Yudai responds with disgust: ‘You’re trying to buy a child with money?’, he asserts angrily, ‘You never lost at anything. You can’t understand how other people feel’. Privilege is contrasted with its opposite; however, Like Father, Like Son avoids becoming a didactic tract and represents both Keita and Ryusei as happy in their own ways.

The story gains an added sense of complexity when we discover that Ryota was raised by a distant father and a step-mother who, it seems, cared for Ryota and his brother as if they were her own children. Ryota visits his parents, who display opposing viewpoints about the nature/nurture debate. ‘Listen, it’s in the blood’, Ryota’s father asserts, ‘For humans and horses, it’s all about bloodlines’. However, Ryota’s step-mother has a different point of view: ‘Despite what your father said, if you live together, you don’t have to be related’, she reminds Ryota, ‘You love each other, you start to look like one another [….] At least, that’s how I felt raising you boys’. This relationship between Ryota and his step-mother is compounded elsewhere in the story, when Ryota confronts the nurse who swapped Keita and Ryusei and finds that the nurse’s adolescent step-son comes to her defence, presumably seeing echoes in this of Ryota’s own relationship with his step-mother. Elsewhere, Ryota questions, ‘Can you really love a child without your blood?’, and he’s answered by Yudai, who tells him ‘The only reason you care so much about whether he [Ryusei/Keita] resembles you or not is because you’re a man who feels no real connection to his child’. Later, Ryota is offered some more advice by Yudai. Yudai enjoys flying kites with his children, and Ryota observes that ‘My father wasn’t the type to fly kites with his children’. ‘But you don’t have to be like your father’, Yudai tells him. The film climaxes with a confused and frustrated Keita running away from both families. He is followed by a devastated Ryota, who tells the boy, ‘I wasn’t a very good daddy, but I was your daddy’.  A father’s connection to his son, and the manner in which sons grow up to be like their fathers, is the overriding theme of After the Storm. As the film opens, an unshaven and dishevelled Ryota steps off a train at Kiyose Station on his journey to visit his mother. Ryota plans to use the visit as a pretext: he intends to raid his father’s possessions to see if there is anything worth pawning. Ironically, the film reveals later, his father did the same thing with Ryota’s possessions, pawning them in order to pay off his gambling debts. Ryota’s father even went so far as claiming that the young Ryota had a tumour, with the intention of currying sympathy with the pawnshop owner. The film also stresses the similarities between Ryota and his father when Ryota approaches his sister and asks for a loan, and in response she reminds Ryota that their father also used to borrow money from her. A father’s connection to his son, and the manner in which sons grow up to be like their fathers, is the overriding theme of After the Storm. As the film opens, an unshaven and dishevelled Ryota steps off a train at Kiyose Station on his journey to visit his mother. Ryota plans to use the visit as a pretext: he intends to raid his father’s possessions to see if there is anything worth pawning. Ironically, the film reveals later, his father did the same thing with Ryota’s possessions, pawning them in order to pay off his gambling debts. Ryota’s father even went so far as claiming that the young Ryota had a tumour, with the intention of currying sympathy with the pawnshop owner. The film also stresses the similarities between Ryota and his father when Ryota approaches his sister and asks for a loan, and in response she reminds Ryota that their father also used to borrow money from her.

Ryota’s estrangement from his son Shingo is heartbreaking. Ryota clearly loves the boy and doesn’t want him to follow in Ryota’s footsteps, much as Ryota didn’t want to follow in the footsteps of his father but inevitably did. Although clearly struggling with his parental responsibilities, Ryota has Shingo’s best interests at heart and is dismayed when he uses his skills as a private investigator to follow his ex-wife and sees her in a restaurant with her new lover, a smarmy twerp who spitefully insists that Shingo should be forbidden from seeing both Ryota and Ryota’s mother. (As if to hammer home just how much of an utter arsebasket this man is, the film also shows him damning Ryota’s novel with vague, half-arsed criticisms.) The film touches on the conventions of film noir in its depiction of Royta’s work as a PI. He’s seen skulking through the streets, the depiction of the work of a private investigator being in line with other pictures like Polanski’s Chinatown (1974): like J J Gittes in that film (or perhaps M Emmet Walsh’s sleazy PI in the Coen Brothers’ Blood Simple, 1984), Ryota is involved in seedy divorce cases, using various sleazy tactics to ‘prove’ infidelity. (‘We better thank the times, these petty days we live in’, Ryota’s boss, ex-detective Yamabe, states.) Ironically, Ryota’s relationship with his ex-wife collapsed not because of an affair, but because of Ryota’s gambling habits and lack of responsibility.  Ryota’s mother faced the same issues in her relationship with Ryota’s father, though she remained married to him until his death. However, Ryota’s father’s irresponsibility with money led to Ryota’s mother being stuck in a run-down flat when many of their contemporaries moved into the newer, more up-market condominiums nearby. Foregrounding her frustrated aspirations to live in this condos, Ryota’s mother has become part of a classical music appreciation group which meets in the condominium owned by her friend Mr Niida. Ryota’s mother faced the same issues in her relationship with Ryota’s father, though she remained married to him until his death. However, Ryota’s father’s irresponsibility with money led to Ryota’s mother being stuck in a run-down flat when many of their contemporaries moved into the newer, more up-market condominiums nearby. Foregrounding her frustrated aspirations to live in this condos, Ryota’s mother has become part of a classical music appreciation group which meets in the condominium owned by her friend Mr Niida.

Kyoto chastises Ryota for his lack of enthusiasm vis-à-vis Shingo’s development during their marriage: ‘If you’re that interested in being a good father, why didn’t you try harder’. As if to validate the dictum most famously espoused in Joni Mitchell’s ‘Big Yellow Taxi’ (‘You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone’), Ryota desperately seeks to become involved in Shingo’s life only after his marriage to Kyoto has been broken seemingly beyond repair. ‘I wonder why it is that men can’t love the present’, Ryota’s mother observes late in the film, ‘They wither spend their time chasing what’s lost or dreaming of what’s beyond their reach’. During the same conversation with his mother, Ryota notes that he wonders what his father really wanted for his life, suggesting that his father never achieved his ambitions because of ‘the times’. In response, Ryota’s mother asserts that men always blame ‘the times’ for their failures, adding that in truth ‘Life is simple’.

Video

The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec. I Wish is presented uncut, with a running time of 128:24 mins and taking up 27.7Gb of space on its disc. The screen ratio is 1.85:1, commensurate with the film’s intended screen ratio. I Wish seems to have been shot on 35mm, using the Arricam and Zeiss/Angenieux lenses and on high-speed Fuji Eterna stock. The film was shot in a documentary-style. The presentation has quite a ‘digital’ appearance here, the dynamic range seeming surprisingly flat for a picture apparently shot on 35mm. The level of detail is good and a step above DVD but some of the long shots look very soft and muddied. Colours are naturalistic and resolved well, and contrast levels are good – with defined midtones and deep blacks. The encode to disc is solid with no artifacting but the grain structure seems muted, especially considering the picture was shot on high-speed Fuji Eterna stock. Like Father, Like Son is uncut and runs for 121:00 mins, filling 30.9Gb on its disc. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film is photographed through very stately, static compositions, their glacial Kubrickian iciness emphasised through the use of classical music on the soundtrack. Colours are again naturalistic and consistent throughout the picture. The film also seems to have been shot on 35mm film, using Kodak Vision3 250D 5207 and Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 stock. The level of detail is good throughout but some shots seem a little ‘flat’ and lacking in depth. Contrast levels are good, with balanced highlights and defined midtones, but blacks sometimes seem a little ‘crushed’. Finally, the encoded to disc is fine and presents no problems. Running for 117:22 mins and taking up 28.6Gb of space on its disc, After the Storm was photographed on 35mm stock, using Kodak Vision3 500T 5219. The presentation here is very good: the image is clear and detailed throughout, fine detail being present in close-ups. Contrast levels are good, with defined midtones, but the dynamic range seems a little ‘clipped’ in places – though with much greater depth to the highlights and midtones than the two earlier films, especially I Wish. Colours are again naturalistic and consistent throughout. The encode to disc is pleasing and presents no issues. I Wish

Like Father, Like Son

After the Storm

Audio

Audio for all three films is presented in Japanese DTS-HD MA 5.1 or Japanese LPCM 2.0 stereo, with optional English subtitles. In the case of I Wish, the 5.1 track is far from ‘showy’ but is more full-bodied and deeper than the stereo track. However, both tracks have a good sense of range and depth to them. The tracks for Like Father, Like Son and After the Storm exhibit similar qualities, the latter featuring some more potent ambient sound effects in its 5.1 track. On all three discs, the optional English subtitles are easy to read and problem-free.

Extras

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

- I Wish (128:24) - Introduction by Tony Rayns (22:40). In a new interview, Rayns reflects on a panel discussion he chaired in 2004 which featured Kore-eda, Tsukamoto Shinya and Kitano Takeshi. This was prior to Kore-eda’s major work in feature films, the director then being known mostly for his work in the documentary field. Kore-eda told Rayns that he wanted to make a more ‘popular kind of film’, making something that appealed to a wider Japanese audience. This surprised Rayns at the time, but in retrospect, Rayns argues, this is exactly what Kore-eda seemed to achieve with his subsequent films. This interview is an interesting, thoughtful consideration of Kore-eda’s career. - ‘Family Ties, Pt I’ (20:03). Kore-eda is here interviewed by Jasper Sharp about I Wish at the 2016 BFI London Film Festival. Kore-eda reflects on how he came to be a filmmaker despite originally wanting to work as a novelist, having studies literature at university and feeling that he wasn’t one to work on group projects. Kore-eda talks about the development of I Wish, which changed direction radically after Kore-eda cast the actors who play the two brothers. Kore-eda discusses some of his influences and what he learnt from the filmmakers he admires. Kore-eda’s comments are in Japanese with burnt-in English subtitles. - ‘What Miracle Would You Wish For?’ (40:43). This documentary looks back at the production of I Wish, featuring input from the cast and crew – who begin the documentary by talking about what their personal ‘miracles’ would be. The documentary is presented in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - ‘The Making of I Wish’ (43:02). Featuring plenty of behind-the-scenes and rehearsal footage interspersed with interviews with the principal cast and crew conducted on the set of the film, this documentary offers an insight into the making of the picture and Kore-eda’s methods as a filmmaker. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Soundtrack Featurette (23:16). Kore-eda speaks with Kishida Shigeru, a member of the group (Quruli) who created the song used as the film’s main theme. The pair talk about the film’s music and the process of writing and creating it. Japanese with English subtitles. - Theme Song (7:01). The song by Quruli is presented over a montage of clips from the film and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - Roll Numbers (4:47). A montage of clapper takes is presented here, accompanied by the Quruli track. - Trailers: Teaser (0:46); Theatrical Trailer (1:54); TV Spot X2 (0:48; 0:48).  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

- Like Father, Like Son (121:00) - ‘Family Ties, Pt II’ (11:34). The second part of the interview with Kore-eda by Jasper Sharp at the 2016 BFI London Film Festival, the comments here focus on Like Father, Like Son. Kore-eda reflects on the success of this particular picture, which he attributes to the presence of Fukuyama in the cast. The film’s success, Kore-eda says, made it easier for him to pursue his subsequent projects. He says that the film was rooted in his experiences as a father and his reflections on his own relationship with his child. Again, Kore-eda speaks in Japanese with burnt-in English subtitles. - ‘Nature Vs Nurture’ (19:08). Alexander Jacoby discusses Like Father, Like Son, beginning with a comparison between Kore-eda and Ozu. Jacoby discusses the film’s juxtaposition of the two families and reflects on the picture’s examination of the nature/nurture debate. - Selected Scene Commentary (67:43). Kore-eda speaks alongside Fukuyama and Lily Franky. The director and two actors provide a visual commentary, discussing scenes from the film that are shown in a picturebox in the corner of the screen. Their comments are exhaustive and engage thoroughly with the film’s themes and its production. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Like Father, Like Son in Cannes (22:35) Here, the viewer is presented with footage from the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, where the film had its European premiere. The footage is apparently culled from a Japanese television broadcast. This is accompanied by a Q&A with Kore-eda and Fukuyama. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Japanese Premiere Q&A (12:18). Kore-eda and the film’s cast are interviewed in an onstage Q&A that followed the 2013 premiere of the film in Japan. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - ‘In Conversation with Kore-eda: Masharu Fukuyama’ (11:16). Kore-eda and Fukuyama deliver a ‘teach-in’ to an audience following a screening of the film in 2013. They discuss elements of Fukuyama’s performance and the subtleties of constructing character through action. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Wrap Footage (6:08). Footage of the end-of-shooting celebrations are presented in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Trailers: Trailer 1 (0:36); Trailer 2 (0:56); Trailer 3 (1:44); Trailer 4 (0:17); Trailer 5 (0:32).  DISC THREE: DISC THREE:

- After the Storm (117:22) - ‘Family Ties, Pt III’ (15:35). Again, Kore-eda and Jasper Sharp speak from the 2016 BFI London Film Festival. Their comments here focus on After the Storm and the manner in which the film can be regarded as a companion piece to Kore-eda’s earlier film Still Walking. Kore-eda’s comments are once again in Japanese with burnt-in English subtitles. - ‘The Making of After the Storm’ (73:08). Narrative by actor Yoshizawa Taiyo, this documentary looks at the preproduction for After the Storm, examining the location scouting, script doctoring and production design of the feature, and continues by offering an insight into the production phase. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Roll Numbers (5:22). A montage of clapper takes from the production is accompanied by music. - ‘The Making of the Theme Song Music Video’ (7:51). The shooting of the music video made to accompany the film is shown via behind-the-scenes footage. Japanese with optional English subtitles. Trailer (1:40).

Overall

At the heart of all three stories is the relationship between parents and their children – especially between fathers and their young sons. The films are thoughtful but not didactic, emotionally engaging but not shallow. Kore-eda strikes a balance between soap opera-esque examination of family dynamics and philosophical examination of modern issues facing families and relationships between children and their parents. All three pictures are incredibly strong. Their presentations here are solid, though After the Storm gets a significantly more pleasing presentation than the two earlier features. The films are also accompanied by some excellent – in fact, exhaustive – contextual material. The new interviews are illuminating but the superb documentaries featuring footage of the films’ production periods offer striking insight into Kore-eda’s processes as a film director. This is an incredibly good release of three films from a fascinating contemporary director. At the heart of all three stories is the relationship between parents and their children – especially between fathers and their young sons. The films are thoughtful but not didactic, emotionally engaging but not shallow. Kore-eda strikes a balance between soap opera-esque examination of family dynamics and philosophical examination of modern issues facing families and relationships between children and their parents. All three pictures are incredibly strong. Their presentations here are solid, though After the Storm gets a significantly more pleasing presentation than the two earlier features. The films are also accompanied by some excellent – in fact, exhaustive – contextual material. The new interviews are illuminating but the superb documentaries featuring footage of the films’ production periods offer striking insight into Kore-eda’s processes as a film director. This is an incredibly good release of three films from a fascinating contemporary director.

References: Bingham, Adam, 2015: Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since ‘Hana-Bi’. Edinburgh University Press Bradshaw, Peter, 2015: ‘Hirokazu Kore-eda: “They compare me to Ozu. But I’m more like Ken Loach”’. [Online.] https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/21/hirokazu-kore-director-our-little-sister-interview Click to enlarge: I Wish

Like Father, Like Son

After the Storm

|

|||||

|