|

|

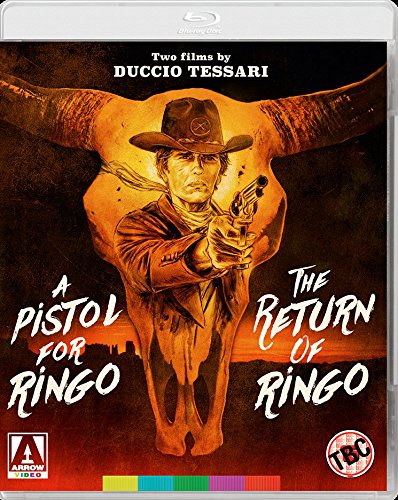

The Film

A Pistol for Ringo & The Return of Ringo: Two Films by Duccio Tessari  Una pistola per Ringo (A Pistol for Ringo or A Gun for Ringo, Duccio Tessari, 1965) takes place at Christmas. Angel Face (aka Ringo, played by Giuliano Gemma) has been acquitted for killing one of the notorious Benson brothers. He is due to arrive in a small border town, and the sheriff, Ben (George Martin), rides out to intercept Ringo. However, the four other Benson brothers beat the sheriff to it, and they face off against Ringo. In front of a crowd of awestruck children, Ringo draws the fastest and kills all four Benson brothers. The sheriff arrests him and places him in a cell. Una pistola per Ringo (A Pistol for Ringo or A Gun for Ringo, Duccio Tessari, 1965) takes place at Christmas. Angel Face (aka Ringo, played by Giuliano Gemma) has been acquitted for killing one of the notorious Benson brothers. He is due to arrive in a small border town, and the sheriff, Ben (George Martin), rides out to intercept Ringo. However, the four other Benson brothers beat the sheriff to it, and they face off against Ringo. In front of a crowd of awestruck children, Ringo draws the fastest and kills all four Benson brothers. The sheriff arrests him and places him in a cell.

A gang led by Sancho (Fernando Sancho) crosses the Rio Grande and arrives in the town. The gang robs the bank, blowing the safe with dynamite and shooting civilians indiscriminately. The bandits ride out of town, pursued by a posse. However, the outlaws take shelter at the ranch of the sheriff’s fiancée Ruby (Lorella De Luca) and her father, Major Clyde (Antonio Casas). A bullet lodged in his shoulder from the shoot-out in town, Sancho demands that the sheriff offer the bandits safe passage to the Rio Grande, or they will begin killing the hostages at a rate of two per day – beginning with the ranch-hands and working their way up to Ruby and her father. The sheriff turns to Ringo for help, realising that Sancho’s gang won’t recognise him. Ringo offers his services, but at a cost of 30% of the money stolen by Sancho. Ringo rides out to the ranch and persuades Sancho that he can help him escape with the money. Ringo assists Sancho by removing the bullet from the bandit’s shoulder. Much to the chagrin of Ruby, Major Clyde grows closer to Dolores (Nieves Navarro), a member of Sancho’s gang, and she responds by becoming increasingly ladylike. As Christmas Day approaches, Sancho plots to escape from the ranch and cross the Rio Grande. Meanwhile, Ringo must devise a way in which to thwart this.  Il ritorno di Ringo (The Return of Ringo, Duccio Tessari, 1965) opens in the border town of Mimbres which has been taken over by the Fuentes brothers, Paco (George Martin) and Esteban (Fernando Sancho), and their gang following the discovery of gold nearby. Into this town rides Montgomery Brown (Giuliano Gemma), the son of a senator, who has been away for a number of years, fighting for the Union in the Civil War. Brown returns to find his father dead, murdered by the Fuentes, and the town dominated by an anti-Anglo sentiment. Brown decides to masquerade as a Mexican peasant in order to infiltrate the town and investigate how and why it has changed so much. Il ritorno di Ringo (The Return of Ringo, Duccio Tessari, 1965) opens in the border town of Mimbres which has been taken over by the Fuentes brothers, Paco (George Martin) and Esteban (Fernando Sancho), and their gang following the discovery of gold nearby. Into this town rides Montgomery Brown (Giuliano Gemma), the son of a senator, who has been away for a number of years, fighting for the Union in the Civil War. Brown returns to find his father dead, murdered by the Fuentes, and the town dominated by an anti-Anglo sentiment. Brown decides to masquerade as a Mexican peasant in order to infiltrate the town and investigate how and why it has changed so much.

Brown is particularly interested in finding out what has become of his wife Hally (Lorella Di Luca). He discovers that Hally is still living in the family home and has been ‘taken’ by Paco Fuentes, who intends to marry her. Brown teams up with Mimbres’ florist, Morning Glory (in the Italian version, named Myosotis – the ‘forget-me-not’, and played by Manuel Muniz), who offers the ‘stranger’ a job and a place to stay. Brown is also introduced to fortune teller Rosita (Nieves Navarro), who is allied with the Fuentes but displays an attraction for the town’s new inhabitant. Brown discovers that the Fuentes murdered his father. Brown also discovers that he has a young daughter, Elizabeth; Hally presumably gave birth to her whilst Brown was at war. Paco stages the funeral of Brown, intending to convince Hally that her husband is dead so that he may persuade her to marry him. During the fiesta thrown by Paco at the Brown house to celebrate his engagement to Hally, Morning Glory is asked to provide the flowers. He and the disguised Brown arrive at the house, Brown taking the opportunity to explore it and see his daughter once again. However, Brown is discovered by the Fuentes, who believe he was simply trying to steal some of the valuables. As punishment, in a ritualistic display Brown is stabbed through the gun hand by Paco. Brown learns to shoot with his left hand and abandons his disguise before teaching the townsfolk to fight back and leading them against the occupying forces of the Fuentes gang.  A Pistol for Ringo was a Spanish-Italian coproduction, financing coming from Producciones Cinematograficas Balcazar and Produzioni Cinematografiche Mediteranee. Much of the film – the scenes revolving around the town – was shot on the Producciones Cinematograficas Balcazar Western town set, situated at Esplugues De Llobregat near Barcelona. Some location work was completed in Almeria and San Jose. Gemma had previously collaborated with Duccio Tessari on the peplum Arrivano i titani (Sons of Thunder/My Son, the Hero/The Titans, 1962), in which Gemma played Krios, a young Titan who is released from Hell in order to take revenge on Cadmus (Pedro Armendari), the king of Crete who has angered the gods by murdering his wife. Gemma has suggested that his roles as Ringo and Krios were ‘essentially the same’, and that he was ‘simply in a different costume and a different setting’ (Hughes, 2006: np). Howard Hughes has suggested that this highlights the extent to which the genre fads (filone) in Italy during the 1960s and 1970s were, on a narrative level, interchangeable: the stories of the pepla, the westerns all’italiana and poliziesco all’italiana films were often almost identical, as were their casts and characters, it was only the outer form/iconography/visual paradigms that were changed (ibid.). A Pistol for Ringo was a Spanish-Italian coproduction, financing coming from Producciones Cinematograficas Balcazar and Produzioni Cinematografiche Mediteranee. Much of the film – the scenes revolving around the town – was shot on the Producciones Cinematograficas Balcazar Western town set, situated at Esplugues De Llobregat near Barcelona. Some location work was completed in Almeria and San Jose. Gemma had previously collaborated with Duccio Tessari on the peplum Arrivano i titani (Sons of Thunder/My Son, the Hero/The Titans, 1962), in which Gemma played Krios, a young Titan who is released from Hell in order to take revenge on Cadmus (Pedro Armendari), the king of Crete who has angered the gods by murdering his wife. Gemma has suggested that his roles as Ringo and Krios were ‘essentially the same’, and that he was ‘simply in a different costume and a different setting’ (Hughes, 2006: np). Howard Hughes has suggested that this highlights the extent to which the genre fads (filone) in Italy during the 1960s and 1970s were, on a narrative level, interchangeable: the stories of the pepla, the westerns all’italiana and poliziesco all’italiana films were often almost identical, as were their casts and characters, it was only the outer form/iconography/visual paradigms that were changed (ibid.).

A Pistol for Ringo offers a playful approach to the paradigms of the Western; the Christmas setting is incongruous and in juxtaposition with the iconography (sun-baked desert towns, etc). The film opens in the main street of the town, two cowboys walking towards one another. The audience might expect a showdown, but these two cowboys stop abruptly, then shake hands and wish one another a happy Christmas. In another light touch, Ringo drinks only milk, like James Stewart’s character in Destry Rides Again (George Marshall, 1939). In contrast with the classic laconic cowboy, Ringo is also very talkative, offering aspects of his personal philosophy at various points in the story (‘Don’t look for trouble; let it come by itself’). When Sancho’s gang rob the town’s bank early in the narrative, the film displays its tendency to jump abruptly from comedy (Sancho telling the bank manager that, having witnessed the gang blow the safe with dynamite, ‘Next time you lose your key, you’ll know how to get the safe open’) to stark violence (civilians being shot down in the street in a manner that pre-empts the Starbuck massacre in Sam Peckinpah’s later The Wild Bunch, 1969).  The threat of sexual violence bubbles beneath the surface of the picture, one or more of Sancho’s gang threatening to rape Ruby at various points in the story. For his part, Sancho mostly prevents such activity from taking place, telling Ruby ‘Don’t be afraid. Nothing will happen to you. You’re under my protection’. However, when the gang first arrive at the ranch, Sancho is gravely wounded, a bullet buried in his shoulder. Upon his arrival, Ringo offers to help, asserting that he has experience of treating a similar wound in a horse. Sancho’s relationship with his gang has some strong echoes of Burl Ives’ role as Captain Jack Bruhn in Andre de Toth’s Day of the Outlaw (1959). In that picture, Bruhn’s gang of outlaws holds an entire town hostage; Bruhn, who is injured with a similar bullet wound to Sancho, keeps his gang in check, preventing them from rampaging through the town and raping the womenfolk – principally Helen Crane (Tina Louise). However, Bruhn’s days are numbered, even after the town’s veterinarian removes the bullet, and the presence of the outlaws threatens to explode with unconscionable violence. In A Pistol for Ringo, Sancho recovers very well after Ringo removes the bullet from his shoulder, but the narrative leads inexorably to a violent conclusion anyway. The scenes in which the bandits, holding the residents of the ranch hostage, play a version of Russian roulette with the ranch-hands in order to determine which two of them should die that day, has a resonance for the political violence of the post-1968 anni di piombo (‘Years of Lead’) that followed the Piazza Fontana bombing and the activities of the Brigate Rossi (‘Red Brigades’). This is compounded when the bandits tell the sheriff’s posse, assembled outside, via a note accompanying a ranch-hand’s corpse that ‘We’re tired of killing labourers. Tomorrow, we’ll start on the owners’. Outside, the townsfolk are torn between those who want to appease Sancho and his gang and seek as peaceable a resolution to the conflict as possible, and those who believe that the ranch should be stormed regardless of the presence of the hostages. The threat of sexual violence bubbles beneath the surface of the picture, one or more of Sancho’s gang threatening to rape Ruby at various points in the story. For his part, Sancho mostly prevents such activity from taking place, telling Ruby ‘Don’t be afraid. Nothing will happen to you. You’re under my protection’. However, when the gang first arrive at the ranch, Sancho is gravely wounded, a bullet buried in his shoulder. Upon his arrival, Ringo offers to help, asserting that he has experience of treating a similar wound in a horse. Sancho’s relationship with his gang has some strong echoes of Burl Ives’ role as Captain Jack Bruhn in Andre de Toth’s Day of the Outlaw (1959). In that picture, Bruhn’s gang of outlaws holds an entire town hostage; Bruhn, who is injured with a similar bullet wound to Sancho, keeps his gang in check, preventing them from rampaging through the town and raping the womenfolk – principally Helen Crane (Tina Louise). However, Bruhn’s days are numbered, even after the town’s veterinarian removes the bullet, and the presence of the outlaws threatens to explode with unconscionable violence. In A Pistol for Ringo, Sancho recovers very well after Ringo removes the bullet from his shoulder, but the narrative leads inexorably to a violent conclusion anyway. The scenes in which the bandits, holding the residents of the ranch hostage, play a version of Russian roulette with the ranch-hands in order to determine which two of them should die that day, has a resonance for the political violence of the post-1968 anni di piombo (‘Years of Lead’) that followed the Piazza Fontana bombing and the activities of the Brigate Rossi (‘Red Brigades’). This is compounded when the bandits tell the sheriff’s posse, assembled outside, via a note accompanying a ranch-hand’s corpse that ‘We’re tired of killing labourers. Tomorrow, we’ll start on the owners’. Outside, the townsfolk are torn between those who want to appease Sancho and his gang and seek as peaceable a resolution to the conflict as possible, and those who believe that the ranch should be stormed regardless of the presence of the hostages.

Sancho’s gang seems fairly progressive, giving a key role to a female gunslinger, Dolores. Ruby’s father’s relationship with Dolores has more than a touch of Pygmalion to it, Clyde providing Dolores with the confidence to believe that she can be a ‘lady’ rather than a bandit. (The film, in the Freudian terms that bubble beneath many westerns all’italiana, frames these two positions as mutually exclusive.) As she begins to fall under the spell of Clyde, he transforms her, like Henry Higgins lording over Eliza Doolittle’s metamorphosis, which takes place towards the end of the picture when Dolores enters a scene wearing a dress that belonged to Clyde’s dead wife (Ruby’s mother). Sancho’s gang seems fairly progressive, giving a key role to a female gunslinger, Dolores. Ruby’s father’s relationship with Dolores has more than a touch of Pygmalion to it, Clyde providing Dolores with the confidence to believe that she can be a ‘lady’ rather than a bandit. (The film, in the Freudian terms that bubble beneath many westerns all’italiana, frames these two positions as mutually exclusive.) As she begins to fall under the spell of Clyde, he transforms her, like Henry Higgins lording over Eliza Doolittle’s metamorphosis, which takes place towards the end of the picture when Dolores enters a scene wearing a dress that belonged to Clyde’s dead wife (Ruby’s mother).

The sheriff, played by Jorge Martin, is an interesting addition to the cast of A Pistol for Ringo. Atypically for a western all’italiana, the film’s sheriff is incorruptible and well-intentioned, though he is naïve in the face of the marauding gang that take his fiancée and her father hostage. He requires the more canny skills of Ringo to save the day. The two characters – Ringo and the sheriff – complement each other, leading inevitably to competition for the affections of Ruby. In some ways, the relationship between the sheriff and Ringo may be compared with the relationship between Joe Starrett (Van Heflin) and Shane (Alan Ladd) in Shane (George Stevens, 1953). Ringo, like Shane (and the protagonists of many ‘adult Westerns’ of the 1950s, such as Ethan in John Ford’s The Searchers, 1956), has the skills and savvy required to protect the society depicted in the film but these are also the skills that ensure that he can never take a settled place within society. His departure from the town at the end of the picture is inevitable, in line with the conventions of most Westerns that feature ‘gunslinger’ plots in which a hero rides in from the wilderness and teaches the sodbusters how to fight.  Ultimately, A Pistol for Ringo feels much more like an American Western than many of its contemporaries, such as the Leone films or Sergio Corbucci’s Django (1966), for instance. Ultimately, A Pistol for Ringo feels much more like an American Western than many of its contemporaries, such as the Leone films or Sergio Corbucci’s Django (1966), for instance.

In terms of the film’s light-hearted approach to the material, in a script that is filled with jokes and even some heavy slapstick, Austin Fisher has compared A Pistol for Ringo’s depiction of violence with that of Shane. Fisher points to the early sequence in A Pistol for Ringo in which Ringo stages a confrontation between the four Benson brothers who have come to take revenge upon him (Fisher, 2014: 72). Ringo shoots and kills these four assassins effortlessly, in front of an enthralled audience of children with whom Ringo has previously been playing hop-scotch; in Shane, Shane’s climactic act of violence against the film’s chief villain, the hired gun played by Jack Palance, is watched by young Joey Starrett (Brandon De Wilde), who idolises Shane. Fisher suggests in his comparison of these two films that ‘in Tessari’s West killing is no longer a last resort or a regenerative force, but merely a stylish, casual and frequent game’: the ‘shocking and visceral’ violence of Shane is replaced with violence that results in ‘no signs of pain or distress’ (ibid.). Alex Cox has gone further, suggesting that A Pistol for Ringo is dominated by sharply-defined, almost nihilistic violence: Cox points to Sancho’s promise to kill two of the servants for every day that the siege continues, suggesting that ‘Underlying the cutesy townspeople and hacienda romances is a refreshing groundbed of Italian Western meanness: perhaps more profound and pessimistic than Leone’s. The bank robbery is marked by unnecessary killing. The sheriff […] jumps into action as the bandits leave town, and shoots several of them in the back. Back-shooting is to be expected of the bad guys, but the sheriff?’ (Cox, 2010: np). Cox also notes that Ringo is a character whose complexities belie his apparent simplicity: he is ‘strong, a deadly gunfighter, and a clever strategist, but he’s also like a child’ and is introduced playing hop-scotch with a group of children (Cox, op cit.). Ringo seems to have the potential to be a turncoat, at one point asserting that his father was an engineer in the Civil War and he fought ‘for the North. At first he was with the South, but they were losing. “Never stick with the losers”, he always said. It’s a matter of principle’. He is ‘A Texan [who] can’t understand why Jesus didn’t pack a six-shooter. He’s indifferent to women: his interests are milk and money’ (ibid.). Like Manco (Clint Eastwood) in Sergio Leone’s Per qualche dollaro in piu (For a Few Dollars More, 1965), Ringo tells the bandits he’s working with the law but foregrounds his mercenary nature as a reason why they should trust him (‘I’m either with you at forty per cent, or against you at thirty per cent’): as Cox suggests, both Manco and Ringo are sent by the bandit leader on a mission with other members of the outlaw gang, and both Manco and Ringo use this mission to ‘thin the herd’, executing the outlaws sent to accompany them.  One of a number of interesting westerns all’italiana to feature a heavy focus on the theme of family (alongside the likes of Ferdinando Baldi’s Texas, Addio/Texas, Adios, 1966, and Il pistolero dell’Ave Maria/The Forgotten Pistolero, 1969), The Return of Ringo is a heavier, more brooding film than its predecessor, the script featuring significant input from Fernando di Leo, who in his own films as a director would demonstrate a fascination with themes of fate and predestination which are hinted at in this picture. The story, set mostly in Mimbres, a town on the border with Mexico, has some similarities with American ‘drifter’ Westerns such as Robert Parrish’s The Wonderful Country (1959), in which Robert Mitchum plays an expatriate hired gun who wanders into a US town near the border with Mexico on a business trip for two corrupt Mexican officials; for much of The Wonderful Country, Mitchum’s character adopts the dress of a Mexican, his garb becoming a symbol of his confused identity. Likewise, in The Return of Ringo, Ringo spends much of the film disguised as a Mexican drifter, helping him to avoid being recognised and allowing him to get close to the Fuentes brothers. One of a number of interesting westerns all’italiana to feature a heavy focus on the theme of family (alongside the likes of Ferdinando Baldi’s Texas, Addio/Texas, Adios, 1966, and Il pistolero dell’Ave Maria/The Forgotten Pistolero, 1969), The Return of Ringo is a heavier, more brooding film than its predecessor, the script featuring significant input from Fernando di Leo, who in his own films as a director would demonstrate a fascination with themes of fate and predestination which are hinted at in this picture. The story, set mostly in Mimbres, a town on the border with Mexico, has some similarities with American ‘drifter’ Westerns such as Robert Parrish’s The Wonderful Country (1959), in which Robert Mitchum plays an expatriate hired gun who wanders into a US town near the border with Mexico on a business trip for two corrupt Mexican officials; for much of The Wonderful Country, Mitchum’s character adopts the dress of a Mexican, his garb becoming a symbol of his confused identity. Likewise, in The Return of Ringo, Ringo spends much of the film disguised as a Mexican drifter, helping him to avoid being recognised and allowing him to get close to the Fuentes brothers.

The Return of Ringo was based on Homer’s The Odyssey, Brown in this film returning from a period of time at war in the manner of Odysseus. In The Odyssey, of course, during the twenty years Odysseus spends at war, his home is invaded by over a hundred suitors seeking to marry Odysseus’ wife Penelope. Believed to be dead by many, Odysseus is sought by his son Telemachus, who was an infant when Odysseus left his home. Odysseus is assisted by his friend, the swineherd Eumaeus. Working together, Odysseus and Telemachus eventually slaughter the suitors. It’s easy to see the parallels between The Odyssey and The Return of Ringo: Penelope becomes Hally; Telemachus is replaced with Elizabeth; and Eumaeus becomes Morning Glory. In The Odyssey, Odysseus disguises himself as a beggar in order to surprise his enemies; in The Return of Ringo, Brown adopts the disguise of a Mexican peasant, allowing him to infiltrate the Fuentes gang. Odysseus’ dramatic transformation from beggar to warrior is a major coup-de-theatre in the book; likewise, Tessari’s film makes a major dramatic point when Brown decides to allow his true self to be known to the Fuentes gang, standing in silhouette in a doorway, the desert sand swirling behind him, and shouting out ‘I have returned!’  The link with the previous film is tenuous. The two pictures share many members of the cast and crew, and Brown seems to be carrying the pistol Ringo took from Sancho in the previous picture. However, Brown isn’t referred to as ‘Ringo’ other than in a handful of exchanges in which the dialogue seems to have been adjusted in postproduction in order to crowbar the name ‘Ringo’ into it. The link with the previous film is tenuous. The two pictures share many members of the cast and crew, and Brown seems to be carrying the pistol Ringo took from Sancho in the previous picture. However, Brown isn’t referred to as ‘Ringo’ other than in a handful of exchanges in which the dialogue seems to have been adjusted in postproduction in order to crowbar the name ‘Ringo’ into it.

As in a number of other noteworthy Italian Westerns (such as Sergio Corbucci’s Django, 1966), the protagonist is a veteran of the Civil War who fought for the North. The film inverts the usual anti-Mexican bias of most traditional Westerns (for example, The Wonderful Country). During Brown’s absence, Mimbres has been taken over by the Fuentes brothers following the discovery of gold nearby. The Fuentes are prejudiced against both Anglos and lowly Mexican peasants: they hang a sign outside the saloon which reads ‘No Entry for Dogs, Gringos and Beggars’. Brown decides to disguise himself as a Mexican peasant but is still met with disdain by the Fuentes when they offer him a job of work and he refuses, dryly asserting that he has already eaten that day. Mimbres is now a violent place (when he first arrives in town, Brown sees a man shot and killed for apparently little reason), and disguised as a Mexican labourer Brown is advised by the sheriff that ‘You’d better start carrying gun if you want to live very long around here’. When Brown asks the sheriff why he himself does not carry a weapon, the sheriff tells him ‘In my case, it’s different. I’m not a Mexican: I’m an American. An inferior race. And when you’re inferior, you live much longer in Mimbres without a gun’. Whether intentional or otherwise, it’s easy to see Mimbres, with its inversion of typical prejudices enabling a foregrounding of the racial tensions within the town, as a metaphor for the Civil Rights era. Brown’s first encounter with his daughter is in a wooded area, where he spots the child and she approaches him – in his disguise as a Mexican peasant – and, unaware he is her father, hands him a bunch of flowers she has picked. The moment seems intentionally to allude to the scene in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) in which the monster (Boris Karloff) is handed flowers by a young girl, and the monster responds by drowning the child accidentally. The appearance of Elizabeth causes Brown to rethink his plan, which was to kill Hally for betraying him. (Brown is initially under the illusion that Hally willingly chose to ally herself with Paco Fuentes and his brother.)  Brown isn’t an uncomplicated hero. For much of the narrative, he is reluctant to ‘save’ Mimbres owing to the almost pathological subservience many of its remaining residents display towards the Fuentes regime, and perhaps owing to the fact that these people presumably stood by and did nothing – or very little – whilst Brown’s father was killed and the family home seized. Brown criticises their inaction against the Fuentes as like a kind of death: ‘Nobody wants to die, sheriff’, Brown says at one point in the film, ‘But to be afraid means dying a little everyday. A man who isn’t afraid can only die once’. Brown later asks Morning Glory why nobody tried to stop the Fuentes when they first arrived in Mimbres. ‘Well, they’re afraid’, Morning Glory responds, ‘You’ve heard of fear’. Morning Glory adds that when the Fuentes appeared in Mimbres, ‘There was nobody left here. The young men were away fighting. When the war ended, a few of them tried to return. But one by one they were ambushed and murdered even before they got a chance to get bak to town. After that, there was no point in resisting’. After Brown has made his appearance to Hally, he plots to escape with her, telling her that now he is back, they ‘can begin living again’. However, Hally asks ‘What about the others? How can you leave them to suffer here?’ ‘These people are beyond help’, Brown responds, ‘already dead with fear’. Hally tells him that they are not dead, ‘Not yet, but they’ll soon be dead if you really abandon them’. Brown isn’t an uncomplicated hero. For much of the narrative, he is reluctant to ‘save’ Mimbres owing to the almost pathological subservience many of its remaining residents display towards the Fuentes regime, and perhaps owing to the fact that these people presumably stood by and did nothing – or very little – whilst Brown’s father was killed and the family home seized. Brown criticises their inaction against the Fuentes as like a kind of death: ‘Nobody wants to die, sheriff’, Brown says at one point in the film, ‘But to be afraid means dying a little everyday. A man who isn’t afraid can only die once’. Brown later asks Morning Glory why nobody tried to stop the Fuentes when they first arrived in Mimbres. ‘Well, they’re afraid’, Morning Glory responds, ‘You’ve heard of fear’. Morning Glory adds that when the Fuentes appeared in Mimbres, ‘There was nobody left here. The young men were away fighting. When the war ended, a few of them tried to return. But one by one they were ambushed and murdered even before they got a chance to get bak to town. After that, there was no point in resisting’. After Brown has made his appearance to Hally, he plots to escape with her, telling her that now he is back, they ‘can begin living again’. However, Hally asks ‘What about the others? How can you leave them to suffer here?’ ‘These people are beyond help’, Brown responds, ‘already dead with fear’. Hally tells him that they are not dead, ‘Not yet, but they’ll soon be dead if you really abandon them’.

Nevertheless, at the end of the picture Brown’s lack of faith in the townsfolk of Mimbres is misplaced: he manages to stir them into action, and they overcome the Fuentes gang outside the house whilst, symbolically, Brown takes care of business within the building itself, purging his home of the bandits and rescuing his daughter Elizabeth. Unlike Gary Cooper in Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1953) and more in line with Howard Hawks’ response to that picture in Rio Bravo (1958), Brown does not have to face the outlaws alone but rallies together the town’s misfits and down-and-outs, including the eccentric florist Morning Glory, a Native American, the deeply passive sheriff and even Rosita, formerly allied with the Fuentes.  The Return of Ringo contains one of the most striking and memorable sequences of any western all’italiana, when Morning Glory and Brown, still disguised as a Mexican peasant, are invited to the Brown house to provide bouquets for the fiesta thrown by the Fuentes. During the Fiesta, Brown explores the house. In one of the rooms, he closes his eyes and quietly counts the steps, touching various objects in his path (a globe, a portrait of himself and Hally) in a manner that demonstrates his familiarity with this space despite his many years of absence from it. He opens a music box, it chimes swelling into Morricone’s soaring score as Brown visits his daughter in her bed and covers her with her bedsheets. Hally enters the room and is at first horrified to see a stranger in her daughter’s bedroom but quickly recognises her husband beneath his disguise, the red light of the lantern she carries falling on his face. Then, they are disrupted by Esteban, who enters and believes Brown to be a simple thief, leading to the scene in which Brown is punished in an exceptionally cruel manner. The Return of Ringo contains one of the most striking and memorable sequences of any western all’italiana, when Morning Glory and Brown, still disguised as a Mexican peasant, are invited to the Brown house to provide bouquets for the fiesta thrown by the Fuentes. During the Fiesta, Brown explores the house. In one of the rooms, he closes his eyes and quietly counts the steps, touching various objects in his path (a globe, a portrait of himself and Hally) in a manner that demonstrates his familiarity with this space despite his many years of absence from it. He opens a music box, it chimes swelling into Morricone’s soaring score as Brown visits his daughter in her bed and covers her with her bedsheets. Hally enters the room and is at first horrified to see a stranger in her daughter’s bedroom but quickly recognises her husband beneath his disguise, the red light of the lantern she carries falling on his face. Then, they are disrupted by Esteban, who enters and believes Brown to be a simple thief, leading to the scene in which Brown is punished in an exceptionally cruel manner.

Like Lockhart (James Stewart) in Anthony Mann’s The Man from Laramie (1955) or Rio (Marlon Brando) in One-Eyed Jacks (Brando, 1961), Brown is given a crippling and highly symbolic injury to his gun hand by the Fuentes brothers after he is caught ‘stealing’ from the Brown home. Where Lockhart’s hand is shot and Rio’s is crushed with the butt of a shotgun, Brown’s gun hand is pierced with the blade of Paco Fuentes’ knife. This type of injury would be come fairly common in westerns all’italiana, with Franco Nero’s Django (in Sergio Corbucci’s Django, 1966) having his hands crushed by horses, and Silence (Jean-Louis Trintignant) in Il grande silenzio (The Big Silence/The Great Silence, Sergio Corbucci, 1969) facing the villains at the end of the picture with a crippled gun hand too. Leone’s Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966) features a pre-emptive parody of this trend within later westerns all’italiana, when Al Mulock’s one-armed bounty killer squares off against Eli Wallach’s outlaw Tuco with the intention of settling a score for a prior encounter which led to the loss of his gun arm. ‘I've been looking for you for eight months’, the bounty hunter intones, ‘Whenever I should have had a gun in my right hand, I thought of you. Now I find you in exactly the position that suits me. I had lots of time to learn how to shoot with my left’. Before the bounty killer can shoot Tuco, however, Tuco blasts him with a concealed pistol: ‘When you have to shoot, shoot. Don’t talk’, Tuco philosophises dryly.

Video

A Pistol for Ringo has previously been released in a number of versions. Original English-language prints trimmed much of the comedy and the scene in which Ringo removes a bullet from the shoulder of Sancho, and on top of this the UK cinema release suffered cuts imposed by the BBFC. Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation contains a complete version of the film, running 99:02 mins. A Pistol for Ringo has previously been released in a number of versions. Original English-language prints trimmed much of the comedy and the scene in which Ringo removes a bullet from the shoulder of Sancho, and on top of this the UK cinema release suffered cuts imposed by the BBFC. Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation contains a complete version of the film, running 99:02 mins.

The Return of Ringo was treated less severely by its English-language distributors, although the UK cinema release (in 1970) suffered almost four minutes of cuts by the BBFC before it was granted a ‘AA’ certificate. The film is here presented uncut, with a running time of 96:33 mins. Both pictures take up just over 20Gb on the disc each; both A Pistol for Ringo and The Return of Ringo are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. Both films were shot in Techniscope, the 2-perf widescreen process in which many westerns all’italiana were filmed. The Techniscope process achieved a screen ratio approximating 2.35:1 by employing spherical, rather than anamorphic, lenses. It was cost-saving in the sense that, by halving the size of each frame in comparison with anamorphic (4-perf) widescreen processes, Techniscope reduced the negative costs involved in making a film by half. However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by lab costs, which it is said were more expensive for films shot in 2-perf formats like Techniscope; it has also been suggested that increases in lab costs were one of the reasons why 2-perf non-anamorphic widescreen processes such as these became less popular during the late 1970s and the 1980s.  Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense/coarse than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s even more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.) Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense/coarse than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s even more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)

For this release, both films have been restored in 2k from their original negatives. The use of the negatives as the source material for this release means the presentations of both pictures bypass the 4-perf ‘blow up’ process, and as a result, blacks are deep and velvety, in line with Techniscope pictures processed using the dye transfer process than the later Techniscope pictures which were processed using the Kodak colour printing process (and which involved the production of a dupe negative that, as noted above, weakened contrast and produced a coarser grain structure). Likewise, the grain structure of both films is natural and organic and, owing to the source being a new transfer of the negative (bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage), without the coarseness that characterised some of the vintage prints of Techniscope films made after around 1970.  Both films are presented in their original 2.35:1 screen ratio. (Some prior digital-era releases of A Pistol for Ringo, including the SPO DVD released in Japan, have been in a compromised ratio of 1.85:1.) The staging in depth, present throughout both A Pistol for Ringo and The Return of Ringo and facilitated by the Techniscope format, is communicated very well in these presentations, a strong sense of depth being present. Detail is very pleasing, fine detail being present in close-ups of both actors and props. Both films are presented in their original 2.35:1 screen ratio. (Some prior digital-era releases of A Pistol for Ringo, including the SPO DVD released in Japan, have been in a compromised ratio of 1.85:1.) The staging in depth, present throughout both A Pistol for Ringo and The Return of Ringo and facilitated by the Techniscope format, is communicated very well in these presentations, a strong sense of depth being present. Detail is very pleasing, fine detail being present in close-ups of both actors and props.

Both films are in superb shape, with limited damage present, though there are a handful of shots in A Pistol of Ringo that seem to be patched in from a lesser quality source. At the bottom of this review are some large screengrabs (click each image to enlarge it); the first of these screengrabs is an example of a shot that seems to be from a lesser source than the majority of the presentation. In the presentations of both films, contrast levels are good, with defined midtones present throughout and rich, velvety blacks (again, commensurate with 1960s-era dye transfer Techniscope presentations). Colours are consistent throughout both pictures, primary tones (especially hot reds) being particularly rich, and communicate the warm Mediterranean shooting conditions very nicely, though there’s perhaps a slight bias towards yellow in the palette. Both presentations retain the grain structure of 35mm Techniscope pictures produced during the dye transfer era (rather than the more coarse structure of 1970s-era Techniscope productions in which prints were produced via the creation of a dupe negative). Both films have reasonably solid encodes but on close inspection of individual frames perhaps suffer a little owing to the fact that they are included on a single disc. The two films could arguably have benefitted from a little more ‘breathing room’ and been included on separate discs, though this would most likely not have been economically viable. Regardless, the presentations are very film-like and satisfying, and are head and shoulders above any previous home video releases of these two pictures. A Pistol for Ringo

The Return of Ringo

Audio

Both films are presented with the option of viewing them with either an Italian DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with optional English subtitles, or an English DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with optional English HoH subtitles. In the case of both pictures, the English dubs are actually pretty good, though with A Pistol for Ringo the Italian dialogue is a little more dryly witty. (Nevertheless, the English dub contains plenty of moments of comedy too.) In the case of A Pistol for Ringo too, some sections of the English dub seem to be patched in from a slightly lesser source than the majority of the track as well. Nevertheless, both audio tracks display good range. Regarding The Return of Ringo, there are less overt differences between the English and Italian dialogue. The English track for this picture is louder and has some noticeable reverb in comparison with the Italian track. The English track also has some moments of warble and flutter. Nevertheless, it’s in pretty good shape, and both tracks again display good range. Both films are presented with the option of viewing them with either an Italian DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with optional English subtitles, or an English DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with optional English HoH subtitles. In the case of both pictures, the English dubs are actually pretty good, though with A Pistol for Ringo the Italian dialogue is a little more dryly witty. (Nevertheless, the English dub contains plenty of moments of comedy too.) In the case of A Pistol for Ringo too, some sections of the English dub seem to be patched in from a slightly lesser source than the majority of the track as well. Nevertheless, both audio tracks display good range. Regarding The Return of Ringo, there are less overt differences between the English and Italian dialogue. The English track for this picture is louder and has some noticeable reverb in comparison with the Italian track. The English track also has some moments of warble and flutter. Nevertheless, it’s in pretty good shape, and both tracks again display good range.

In the case of both films, the subtitles (both translating the Italian dialogue and transcribing the English dub) are easy to read and free from glaring errors. Again in the case of both films, selecting ‘Italian Version’ from the ‘Setup’ menu results in the film being played with Italian on-screen text too.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Audio commentaries for both films by C Courtney Joyner and Henry C Parke. Joyner and Parke are enthusiastic and knowledgeable about the Western genre, though both commentators are known chiefly for their work on American Westerns rather than westerns all’italiana. Nevertheless, they offer some insightful reflections on both Ringo pictures, considering the films’ relationships with both American Westerns and other examples of the Italian Western – particularly Leone’s Dollars pictures. One particularly interesting section sees the pair reflecting on the use of the name ‘Ringo’ in Westerns and the ambiguity surrounding its origins. The pair struggle with the names of the Italian cast and crew (mispronouncing Duccio Tessari’s first name and Giuliano Gemma’s surname, for instance) and other examples of Italian pronunciation (for example, using the mangled plural noun ‘giallos’) but, given the quality of the observations made in this track, these errors are easy to forgive. - ‘Revisiting Ringo’ (37:56). Tony Rayns has no problems with Italian pronunciations in this newly-filmed interview. Rayns offers a superb contextualisation of both Tessari Westerns included in this set, discussing the work of the director and reflecting on the similarities and differences between Tessari’s pictures and those of his contemporaries. Rayns compares Italian cinema of the 1960s with Hong Kong cinema of the 1970s, suggesting that the Italian film industry ‘had a little field day’ owing to slow take-up of television, leading to the filone principle. This is a superb featurette, Rayns’ encyclopaedic knowledge of film history shining throughout. - ‘They Called Him Ringo’ (21:52). This featurette was created for the Koch Media DVD release of A Pistol for Ringo and sees input from Gemma and Lorella De Luca, who reflect on the casting process and their involvement in the production of the film – including the use of Anglicised pseudonyms. They also talk about their associations with Sergio Leone and Tessari’s input into Per un pugnio di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964). Interviewed separately, the pair speak in Italian with optional English subtitles provided.

- ‘A Greek Western Tragedy’ (26:32). This featurette was also created for Koch Media, for inclusion on their DVD release of The Return of Ringo. It features Lorella De Luca and camera operator Sergio D’Offizi. They talk about the origins of The Return of Ringo and Tessari’s interest in The Odyssey. De Luca recalls that the film was originally to be called ‘L’Odissea dei lunghi fucili’ (‘The Odyssey of the Long Guns’) but D’Offizi recollects that when he became involved, the title was always The Return of Ringo: this is what was written on the clapperboards. Both interviewees speak in Italian, with optional English subtitles provided. - Trailers: A Pistol for Ringo (US: 3:26; German: 3:14); The Return of Ringo (US: 3:25; Italian: 3:26). - Gallery (1:38).

Overall

Both A Pistol for Ringo and The Return of Ringo are strong and distinctive examples of the western all’italiana, contemporaries of the Leone Westerns but different from them in the same manner as Corbucci’s Django, for example. Tessari’s two Ringo Westerns stand in stark relief against one other, however, and new viewers may find themselves having a strong preference for one over the other: this writer has always admired The Return of Ringo greatly, finding its tragic, operatic sensibility more engaging than the more lighthearted approach that Tessari takes in A Pistol for Ringo. (That said, A Pistol for Ringo contains some sharp juxtaposition of fairly bawdy comedy with quite cruel violence – the kind of violence that, in the subsequent anni di piombo, would have stark corollaries in the real world.) Both films are presented very well here. The presentations are solid and film-like throughout, and the contextual material – especially the new interview with Tony Rayns – is packed with information. As a fan of westerns all’italiana since as far back as I can remember, it’s always a pleasure to see such films handled well on home video formats, and this is an excellent release from Arrow Video. References: Cox, Alex, 2010: 10,000 Ways to Die: A Filmmaker’s Take on the Spaghetti Western. Manchester: Kamera Books Fisher, Austin, 2014: Radical Frontiers in the Spaghetti Western: Politics, Violence and Popular Italian Cinema. London: I B Tauris Hughes, Howard, 2006: Once Upon a Time in the Italian West: The Filmgoers’ Guide to Spaghetti Westerns. London: I B Tauris Click to enlarge: A Pistol for Ringo

The Return of Ringo

|

|||||

|