|

|

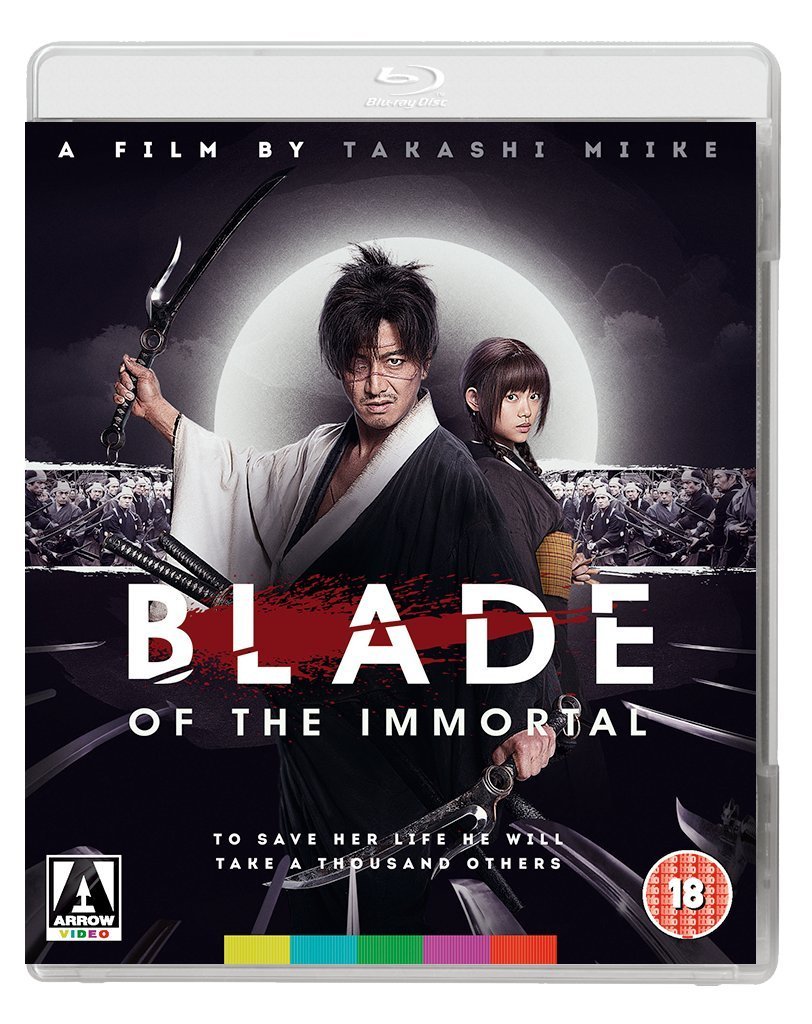

Blade of the Immortal AKA Mugen no jûnin (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th April 2018). |

|

The Film

Blade of the Immortal (Miike Takashi, 2017) Blade of the Immortal (Miike Takashi, 2017)

On the run after turning against his corrupt master, outlaw samurai Manji (Kimura Takuya) is the guardian of his young sister Machi (Sugisaki Hana). Machi has been driven to the edge of madness following Manji’s killing of her husband, a bodyguard for Manji’s lord. Manji’s love for Machi prevents the disgraced samurai from committing seppuku. Manji is cornered by a ronin named Shido (Kaneko Ken) and his hundred-strong gang, who are seeking the reward that has been placed on Manji’s head. Shido captures Machi and kills her, Manji slashing his way through Shido’s entire gang and facing off against Shido. Manji kills Shido but is mortally wounded. He is about to die, released from his responsibility towards his beloved sister Machi and asserting that ‘Life has no meaning now’. However, he is visited by a witch, Yaobikuni (Yamamoto Yoko), who claims to be eight hundred years old. Yaobikuni carves into Manji’s abdomen and places within it ‘sacred bloodworms’ which she promises ‘will live inside you’, granting Manji unwanted immortality. Manji discovers that the bloodworms will even reattach severed limbs. At a martial arts school operated by her father, Rin (also played by Sugisaki Hana) proves herself to be an exceptional martial artist though she is criticised by her mother for her lack of ‘ladylike’ manners. At night, Rin’s father’s martial arts school is visited by members of the Itto-Ryu, led by Kagehisa Anotsu (Fukushi Sota). The Itto-Ryu have been destroying martial arts schools with the intention of absorbing their members, Anotsu believing that ‘only those dedicated to making themselves powerful deserve the name “swordsman”’. Anotsu kills Rin’s father whilst his heavies assault her mother and drag her away. An indefinite period of time later, Rin is visiting her father’s grave when she is visited by Yaobikuni. Rin expresses her desire for revenge and Yaobikuni suggests that Rin should hire a bodyguard – Manji. Rin finds Manji, and he sees in the young woman the image of his dead sister Machi. He reluctantly accepts the job of being Rin’s bodyguard after Rin is confronted by a member of the Itto-Ryu, Kuroi Sabato (Kitamura Kazuki), who has two severed heads stitched to his shoulders – one of these being the head of Rin’s mother. Manji defends Rin from Sabato, killing the deviant in a vicious swordfight. Manji also kills another member of the Itto-Ryu, Magatsu Taito (Mitsushima Shinnosuke), who has been carrying Rin’s father’s sword.  The Itto-Ryu having been asked to head a fencing school for government officials, a proposition which is later revealed to be a trap by the Shogunate, Anotsu becomes aware of the presence of Manji (nicknamed ‘The Hundred Man Killer’) and the deaths of Sabato and Taito. Anotsu asks his men to hunt down Manji and also enlists the help of a female assassin, Otono-Tachibana Makie (Toda Erika). The Itto-Ryu having been asked to head a fencing school for government officials, a proposition which is later revealed to be a trap by the Shogunate, Anotsu becomes aware of the presence of Manji (nicknamed ‘The Hundred Man Killer’) and the deaths of Sabato and Taito. Anotsu asks his men to hunt down Manji and also enlists the help of a female assassin, Otono-Tachibana Makie (Toda Erika).

Manji is confronted by another member of the Itto-Ryu, Shizuma Eiku (Ichikawa Ebizo). Like Manji, Eiku is immortal, having lived for over two hundred years. Eiku’s immortality was bestowed upon him by Yaobikuni also. During a fight with Manji, Eiku reveals he discovered a poison for the bloodworms during the years he spent wandering in Tibet. Eiku poisons his blade, wounding Manji and leading Manji’s bloodworms to slow down the regeneration process. Manji and Rin become associated with a trip of wandering samurai, the Mugai-Ryu, who aim to bring down the Itto-Ryu: Shira (Ichihara Hayato), Gyichi and Hyakurin (Kuriyama Chiaki). Shira proves himself to be an efficient but artless killer, and when Shira kills a defenceless woman during a battle with members of the Itto-Ryu, he is criticised by Rin. Shira strikes Rin, leading to a showdown between himself and Manji, during which Shira escapes, but only after Manji has used a chain weapon to lop off one of Shira’s hands. Manji confronts Gyichi and Hyakurin, who reveal that the Shogunate wishes to crush the Itto-Ryu and has set a trap for them by asking Anotsu to run a fencing school for government officials. Manji is disturbed by this, realising that if the government crushes the Itto-Ryu, Rin will be denied her opportunity for revenge. The stage is set for a final confrontation between Manji and Rin, the Itto-Ryu and Anotsu, and the government forces.  Based on the manga by Samura Hiroaka, Blade of the Immortal is director Miike Takashi’s hundredth directing credit, though it isn’t his hundredth feature film (an error repeated in many of the film’s reviews, as Tom Mes acknowledges in his commentary track). Miike Takashi’s career has been remarkably diverse. Following his beginnings in V-Cinema and his association, in the days of his early feature film career, with highly efficient gangster pictures (including the Black Society trilogy, which Arrow recently released on Blu-ray and DVD, reviewed by us here), Miike achieved international ‘breakout’ success with Audition in 1999 (also released on home video by Arrow and reviewed by us here). Miike’s audience has broadened since then, though Miike has often said that he doesn’t make his films with an international audience in mind, though he is of course pleased if foreign viewers find something engaging in his films. Based on the manga by Samura Hiroaka, Blade of the Immortal is director Miike Takashi’s hundredth directing credit, though it isn’t his hundredth feature film (an error repeated in many of the film’s reviews, as Tom Mes acknowledges in his commentary track). Miike Takashi’s career has been remarkably diverse. Following his beginnings in V-Cinema and his association, in the days of his early feature film career, with highly efficient gangster pictures (including the Black Society trilogy, which Arrow recently released on Blu-ray and DVD, reviewed by us here), Miike achieved international ‘breakout’ success with Audition in 1999 (also released on home video by Arrow and reviewed by us here). Miike’s audience has broadened since then, though Miike has often said that he doesn’t make his films with an international audience in mind, though he is of course pleased if foreign viewers find something engaging in his films.

Regardless of their genre or historical trappings, however, Miike’s films are identifiable by the director’s rebellious, anti-authoritarian, subjectivist worldview. His protagonists are outsiders who often find commonality with other characters simply through the fact that they share outlaw status, this similarity overriding all other differences. At the climax of Blade of the Immortal, Manji and Rin find themselves briefly allied with their mortal enemy Anotsu, Rin criticising the hundreds of government forces who corner Anotsu and refuse him a fair fight one-on-one. (‘You call yourselves samurai?’, Rin asks the government forces, ‘He’s only one man [….] Even killing should be done right’.) In response, Rin’s death is ordered, and Manji comes to her aid. Manji, Rin and Anotsu then fight side-by-side against the government forces before resuming their personal vendetta. Miike’s characteristic nihilistic subjectivism is also present in the picture, when Rin asks Manji to kill Anotsu and the other members of the Itto-Ryu, telling the samurai ‘This isn’t about logic or good and evil. I just want you to kill them’. In a moment that is perhaps anathemical to modern Western sensibilities (where ‘Bad Feelings’ must be cured and/or anaesthetised, a narrative enacted in much mainstream film, television and literature), Manji suggests that trauma is essential to the human condition, telling Rin that ‘No matter how bad the memory, sometimes just remembering it gives you incredible power’.  During his early years making V-Cinema/DTV pictures, Miike learnt how to make movies quickly and efficiently, and also how to differentiate his work from the pack by injecting into the narratives elements of the carnivalesque and moments of graphic violence and sexuality. (These two traits would become foregrounded in some of Miike’s work of the early 2000s – notably 2001’s Visitor Q and Ichi the Killer). Since the success of his 2010 jidaigeki picture 13 Assassins, a remake of Kudo Eiichi’s 1963 picture, Miike directed another period drama set in feudal Japan, a remake of Kobayashi Masaki’s 1962 classic Hara-Kiri (in 2011). With Blade of the Immortal, Miike takes the trappings of the jidaigeki (a lavishly recreated period setting) and infuses them with elements of fantasy (immortality generated by the ‘bloodworms’ with which Manji is infected). However, despite lashings of violence, Miike’s film shows a surprising timidity in adapting the manga, sacrificing some of the more outrageous elements of the source material, perhaps in concession to the requirements of the budget in reaching a larger audience; a long-time Miike viewer might wonder what the Miike of the early 2000s would have done with this material. During his early years making V-Cinema/DTV pictures, Miike learnt how to make movies quickly and efficiently, and also how to differentiate his work from the pack by injecting into the narratives elements of the carnivalesque and moments of graphic violence and sexuality. (These two traits would become foregrounded in some of Miike’s work of the early 2000s – notably 2001’s Visitor Q and Ichi the Killer). Since the success of his 2010 jidaigeki picture 13 Assassins, a remake of Kudo Eiichi’s 1963 picture, Miike directed another period drama set in feudal Japan, a remake of Kobayashi Masaki’s 1962 classic Hara-Kiri (in 2011). With Blade of the Immortal, Miike takes the trappings of the jidaigeki (a lavishly recreated period setting) and infuses them with elements of fantasy (immortality generated by the ‘bloodworms’ with which Manji is infected). However, despite lashings of violence, Miike’s film shows a surprising timidity in adapting the manga, sacrificing some of the more outrageous elements of the source material, perhaps in concession to the requirements of the budget in reaching a larger audience; a long-time Miike viewer might wonder what the Miike of the early 2000s would have done with this material.

In the manga, Manji adopts the sauwastika as his personal symbol, the swastika-type symbol associated with Japanese Buddhism (differentiated from the swastika by the fact that it is left-facing, its points move in a counterclockwise direction); in Japan, the sauwastika is often called the manji. The Manji of the manga carries this symbol on his back. In Miike’s film, the symbol has been change to a transliteration of the symbols for the compound word ‘man-ji’. Elsewhere, the cruel sexual sadism of Shira is underplayed, the narrative eliminating the grievance that exists in the manga between Shira and Taito, Shira having raped Taito’s prostitute lover. The violence is deliriously kinetic, communicated by some frenzied editing and superb fight choreography, and results in some outrageous bloodshed. Despite its temperance of some of the manga’s more outrageous content, Miike’s picture retains the emphasis on violence and bloodshed within its source material: the severed heads, including that of Rin’s mother, that Sabato carries on his shoulders; Shira’s return, in which it’s revealed that following the loss of his hand, Shira sharpened the bones in his forearm into sharp points, using these as a weapon against his enemies.  Miike’s playfulness is exhibited within the picture, the film flirting with the conventions of vampire stories through its examination of the weight of immortality. During their first meeting, Yaobikuni tells Manji that ‘It’s easier when someone else decides life or death for you’, and the rest of the film continues to explore this thesis. Both Manji and the other immortal samurai, Eiku, are pained by their immortality. Manji’s immortality is granted to him by Yaobikuni, almost as a punishment after he kills Shido and his entire gang, commenting that now Machi is dead ‘Life has no meaning’. ‘After you’ve killed all those men?’, Yaobikuni observes, ‘How self-centred!’ When Manji fights and kills Sabato, Manji tells his dying enemy, ‘You’re lucky: you can die’. When Manji fights the other immortal samurai, Eiku, he expresses similar sentiments, telling Manji that in his two hundred years of life, ‘I’ve had five wives and more than that in friends. All dead, while I remain. Death is merciless. However, never dying is far worse’. Later, during their final fight, Eiku tells Mani ‘I’m tired… of being alive’, allowing Manji to kill him. Miike’s playfulness is exhibited within the picture, the film flirting with the conventions of vampire stories through its examination of the weight of immortality. During their first meeting, Yaobikuni tells Manji that ‘It’s easier when someone else decides life or death for you’, and the rest of the film continues to explore this thesis. Both Manji and the other immortal samurai, Eiku, are pained by their immortality. Manji’s immortality is granted to him by Yaobikuni, almost as a punishment after he kills Shido and his entire gang, commenting that now Machi is dead ‘Life has no meaning’. ‘After you’ve killed all those men?’, Yaobikuni observes, ‘How self-centred!’ When Manji fights and kills Sabato, Manji tells his dying enemy, ‘You’re lucky: you can die’. When Manji fights the other immortal samurai, Eiku, he expresses similar sentiments, telling Manji that in his two hundred years of life, ‘I’ve had five wives and more than that in friends. All dead, while I remain. Death is merciless. However, never dying is far worse’. Later, during their final fight, Eiku tells Mani ‘I’m tired… of being alive’, allowing Manji to kill him.

In a further nod to the paradigms of vampire stories, after abducting Rin, Eiku tells her that if she drinks his blood she too will become immortal. Displaying a curious ambivalence towards this story, like someone tintering on the edge of a cliff who wonders what will happen if she leaps from it, Rin semi-reluctantly opens her mouth to drink the blood from a wound on Eiku’s arm which he proffers to her. However, at the last second, Eiku pulls his arm away from Rin and tells her that he was only joking – that the bloodworms cannot be transmitted in this way. The structure of the film – a young woman, seeking revenge, finds herself accompanied by an older male bodyguard who, though initially reluctant to help the girl, discovers during their quest vestiges of his old humanity – is familiar from numerous samurai films and Westerns. In particular, the story has some strong similarities with Charles Portis’ 1968 novel True Grit, adapted twice for the screen (firstly in 1969, by Henry Hathaway and with Kim Darby and John Wayne in the lead roles; and more recently by the Coen Brothers, in 2010, with Hailee Stanfeld and Jeff Bridges). Rin’s first approach to Manji, in which he treats her coldly and derisively, has some strong echoes of Mattie’s approach to the misanthropic US Marshall Reuben ‘Rooster’ Cogburn in True Grit, Mattie seeking Cogburn’s help in avenging the death of her father. Though this type of story has precursors in both Japanese and American culture (from George Stevens’ Shane in 1953 to Renaissance plays), True Grit shifted paradigms by making the young ‘apprentice’ a girl, and its narrative model has been recycled numerous times since: in Luc Besson’s Leon (1994), for example, and more recently in both Bryan Singer’s X-Men (2000) and James Mangold’s Logan (2017). The latter film has some particularly interesting similarities with Blade of the Immortal, in terms of the regenerative powers of the films’ respective protagonists. Most, if not all, of these stories blur the boundaries between the Japanese samurai picture and the American Western, just the kind of genre confusion that has been at the core of the films Miike directed prior to Blade of the Immortal.

Video

Blade of the Immortal takes up just under 30Gb of space on its dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 141:33 mins. Blade of the Immortal takes up just under 30Gb of space on its dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 141:33 mins.

The film was lensed by Kita Nobuyasu (and an interesting interview with the cinematographer, focusing on his work on this picture, appeared in American Cinematographer, reproduced online here). Nobuyasu shot the fight scenes with telephoto lenses and used shorter focal lengths for the dialogue scenes (Goldman, 2017: np). The lenses were predominantly from the Cooke S4 series, Nobuyasu reflecting that many modern lenses are too clinically sharp (ibid.). Nobuyasu also chose to shoot the film digitally, on the Alexa XT Plus, using higher ISO settings to accommodate for the shorter days during the winter months (when the film was in production). Additionally, Nobuyasu chose to shoot digitally to make it easier to accommodate any colour shifting that would need to take place in post-production to avoid the cooler hues of winter light filtering into the completed picture (ibid.). Blade of the Immortal mixes colour footage with monochrome material – the prologue and flashbacks in the main story being presented in black and white. The original intention was for the studio logos to be in monochrome too, but apparently this was prohibited – Warner Bros only allowing their logo to be presented in black and white before films that are entirely in monochrome (ibid.). With the monochrome footage, Miike and Nobuyasu agreed that an elliptical approach to the material was the most relevant, based on the concept that ‘Parts you can’t see don’t need to be seen’ (Nobuyasu, quoted in ibid.). They thus used sharp tonal curves in order to ‘keep the monochrome rigid’, burying information in deep shadows – in a manner inspired by the films of Clint Eastwood, especially Unforgiven (1992) (Nobuyasu, quoted in ibid.). Nobuyasu also suggested that colours in period films should lack heavy saturation, and he explored this in Blade of the Immortal, noting that the richest colours in the film are associated with Rin’s costume (a vivid red), to connote the notion of ‘a beautiful woman standing among filthy men’ (ibid.). The digitally-shot feature is represented very well on this Blu-ray release. Detail is crisp and fine detail is present throughout, especially in closeups. The tonal curves in the monochrome footage seem in line with the intentions of Nobuyasu, as outlined in the ASC interview cited above: contrast is sharp and defined, with deep blacks and rich midtones. Colours are soft yet defined, again in line with Nobuyasu’s comments above. There are no glaring issues with the encode, which carries the feature nicely.

Audio

Audio is presented (in Japanese) via a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track. This is rich and has excellent range, the soundscape bursting alive during the combat scenes. The track is accompanied by two sets of optional subtitles: English and English HoH. These subtitles are easy to read and contain no glaring errors. Another audio option is offered: an audio descriptive track, in LPCM 2.0 stereo.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Tom Mes. Mes begins his commentary by joking that Blade of the Immortal is a long film and that he is unsure whether he ‘will have enough to say’ to fill that period of time. Mes provides a rich examination of the film within the framework of Miike’s career as a whole, discussing its relationship with Miike’s other pictures. It’s an illuminating commentary track, rich in Mes’ acknowledged comprehension of Miike’s work. - ‘Takashi Miike on Blade of the Immortal’ (25:37). In this new interview, lensed at the 2017 London Film Festival, Miike talks about the challenges he faced in bringing the manga to the screen and reflects on the his association with producer Jeremy Thomas. The director talks about how characters are represented through their costume and weapons, and how difficult it is ‘to reproduce [this] faithfully’. He also talks about the cast and his relationships with the actors, reflecting on the moral conflicts in his pictures. Miike speaks in Japanese; burnt-in English subtitles are provided. - ‘Manji vs. 100’ (6:25). This featurette offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse at the fight scene that opens the picture, and is in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - ‘Manji vs. 300’ (11:57). This featurette uses onset footage to look at the shooting of the climactic fight between Manji, Rin, Anotsu and the government forces. It is also in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Interviews (with a ‘Play All’ option): Takuya Kimura (28:42); Hana Sugisaki (10:57); Sota Fukushi (11:56); Hayato Ichihara (7:59); Erika Toda (8:30); Kazuki Kitamura (3:59); Chiaki Kuriyama (3:55); Shinnosuke Mitsushima (5:00); Ebizo Ichikawa (4:16). These interviews with the cast members, who reflect on their roles and Miike’s direction of the picture, are interspersed with behind-the-scenes footage shot during the production. Japanese language, with optional English subtitles. - Stills Gallery (1:07). - Trailer (1:59).

Overall

Though not Miike’s best picture and perhaps a moderately compromised adaptation of the manga, Blade of the Immortal nevertheless displays Miike’s subversive worldview throughout. As with Miike’s other pictures, the film blends genres effortlessly, marrying the jidaigeki with fantasy and emulating the style of American Westerns and westerns all’italiana as much as samurai pictures (though these two forms have often dovetailed: for example, in the relationship between Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and The Magnificent Seven, or between Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars). In condensing the expansive story of the source manga, Miike’s Blade of the Immortal is sometimes relentlessly of one tone: that tone is exhilarating, but it’s nevertheless monotonous, with few shifts in the emotional palette of the picture. With so many conflicts within its narrative, the film’s resolution also arguably contains too many points of climax. It’s a solid picture but could benefit from a little more room for the story to ‘breathe’ – despite the 141 minute running time. That said, it’s a breathless, entertaining action picture that is in many ways an antidote to the pat morality of most action films. Though not Miike’s best picture and perhaps a moderately compromised adaptation of the manga, Blade of the Immortal nevertheless displays Miike’s subversive worldview throughout. As with Miike’s other pictures, the film blends genres effortlessly, marrying the jidaigeki with fantasy and emulating the style of American Westerns and westerns all’italiana as much as samurai pictures (though these two forms have often dovetailed: for example, in the relationship between Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and The Magnificent Seven, or between Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars). In condensing the expansive story of the source manga, Miike’s Blade of the Immortal is sometimes relentlessly of one tone: that tone is exhilarating, but it’s nevertheless monotonous, with few shifts in the emotional palette of the picture. With so many conflicts within its narrative, the film’s resolution also arguably contains too many points of climax. It’s a solid picture but could benefit from a little more room for the story to ‘breathe’ – despite the 141 minute running time. That said, it’s a breathless, entertaining action picture that is in many ways an antidote to the pat morality of most action films.

Arrow’s presentation of this digitally-shot film is very pleasing and seems true to the intentions of the cinematographer. The main feature is accompanied by a very good array of contextual material: Mes’ commentary situates the film within the framework of Miike’s career overall, and the interview with Miike offers insight into his approach to the material. For Miike fans, this is an essential release. References: Goldman, Michael, 2017: ‘Blade of the Immortal: Samurai Cinematographer’. [Online.] https://ascmag.com/articles/blade-of-the-immortal-samurai-cinematographer Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|