|

|

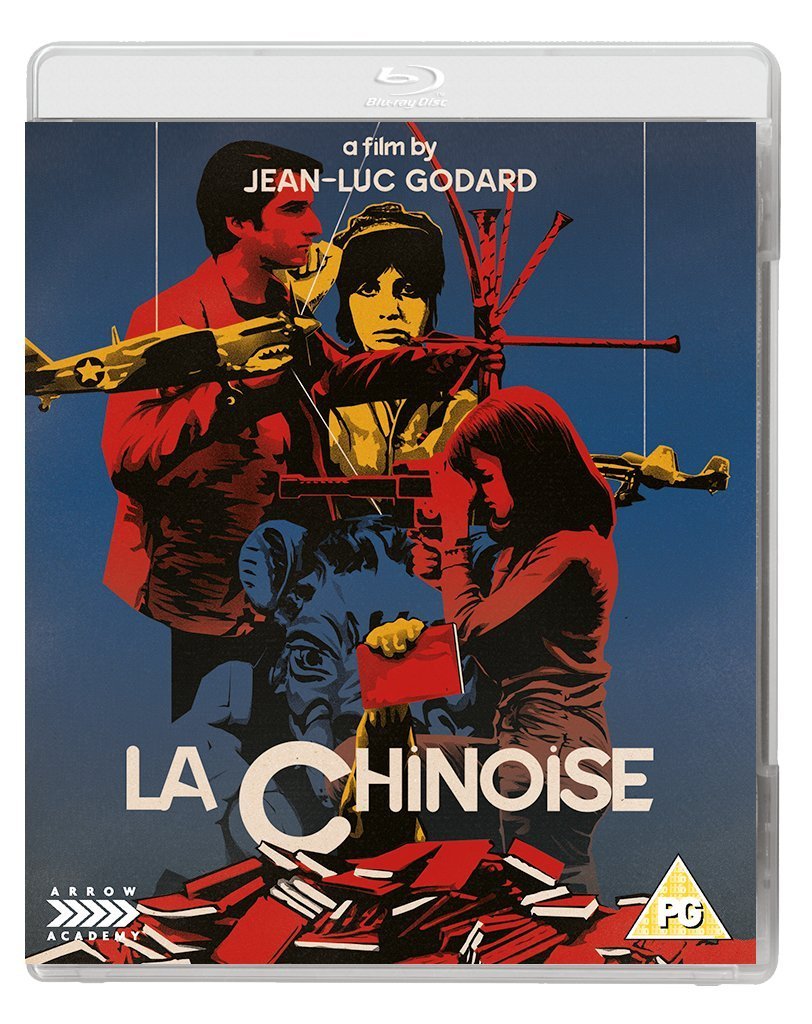

Chinoise (La) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (6th May 2018). |

|

The Film

La Chinoise (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967) La Chinoise (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967)

Taking place predominantly within a small apartment in Paris, La Chinoise examines the lives of five young Maoist students: Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Leaud), Yvonne (Juliet Berto), Henri (Michel Semeniako) and Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin). The students are taking part in a filmed documentary and we see them deliver monologues in which they explore their relationship with Maoist ideology, and engage in discussions amongst themselves. The group argue over their interpretation of Maosim, expelling Henri from the group for his defence of the Nicholas Ray film Johnny Guitar (1954). Veronique proves to be the most committed of the group and advocates violent action as a means of effecting social change, breaking off her relationship with Guillaume and explaining her decision via reference to political rhetoric, before heading out to assassinate the Soviet Minister of Culture. A pivotal film in the career of its director Jean-Luc Godard, La Chinoise marked the point at which Godard turned away from the romantic potential and Hollywood-style narrative preoccupations of earlier films such as A bout de souffle/Breathless (1959) and Le Mépris/Contempt (1963) and fixated on the machinations of radical Leftist youth movements. This was a theme that had bubbled beneath the surface of pictures such as Pierrot le fou (1965) but which became the abiding focus of Godard’s work post-Le Week-end (1967). Both Le Week-end and La Chinoise predicted the ideological and physical violence that would sweep through France and the rest of Europe in 1968, and subsequently Godard would retreat from 35mm feature films into making political films on 16mm with the Dziga Vertov Group alongside Jean-Pierre Gorin. Godard’s post-La Chinoise pictures would receive extremely limited distribution, but they were a clear continuation of the ideological project initiated by this film and Le Week-end.  In its depiction of a group of students whose fascination with Maoist ideology leads one of their number, Veronique, to assert that the only way to effect change (or more precisely, to effect the kind of change that these students desire) is through terrorism, La Chinoise anticipated the events of May 1968 and the political violence that spread throughout Europe during the 1970s via groups like the Rote Armee Faktion/Red Army Faction and the Brigate Rosse/Red Brigades. Alex Ling has suggested that in the case of both La Chinoise and Godard’s later Tout va bien (1972, recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here), there is a tension between Godard’s employment of modernist techniques (in particular, Brechtian distanciation via the use of still photographs and onscreen titles) and a sense of realism ‘in the encyclopaedic scope of their situational analysis’ (Ling, 2013: 183-4). Both films, Ling argues, ‘effectively serve to catalogue the pre- and post-evental worlds of France, 1967, and France, 1972 [….] mapping the political climate in France in the disparate worlds of 1967 and 1972’ (ibid.: 184). In its depiction of a group of students whose fascination with Maoist ideology leads one of their number, Veronique, to assert that the only way to effect change (or more precisely, to effect the kind of change that these students desire) is through terrorism, La Chinoise anticipated the events of May 1968 and the political violence that spread throughout Europe during the 1970s via groups like the Rote Armee Faktion/Red Army Faction and the Brigate Rosse/Red Brigades. Alex Ling has suggested that in the case of both La Chinoise and Godard’s later Tout va bien (1972, recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here), there is a tension between Godard’s employment of modernist techniques (in particular, Brechtian distanciation via the use of still photographs and onscreen titles) and a sense of realism ‘in the encyclopaedic scope of their situational analysis’ (Ling, 2013: 183-4). Both films, Ling argues, ‘effectively serve to catalogue the pre- and post-evental worlds of France, 1967, and France, 1972 [….] mapping the political climate in France in the disparate worlds of 1967 and 1972’ (ibid.: 184).

In some ways, the film anticipates the BBC’s 1980s sitcom The Young Ones (1982-4) in its heavy focus on one setting and the ideological tensions that exist between the students who live in it. The comparison, on its surface, might appear trite, but like The Young Ones Godard’s film oscillates between sympathy for the radical students and subtle mockery for their political posturing. The students are for the bulk of the film’s narrative confined to their apartment, though in its final sequences La Chinoise journeys outside this setting, as Veronique travels via train with one of the lecturers from her university, played by Francis Jeanson, and the pair engage in a dialogue initiated by some of Veronique’s more radical assertions. These include Veronique’s belief that acts of violence should be committed on the sites of French universities, to shock students and staff out of their complacency. (This dialogue draws a parallel between Veronique’s radical affiliations and Francis Jeanson’s publicised sympathies with the Algerian National Movement, leading to his arrest and imprisonment in 1960.)  Carrying some loose similarities with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1872 novel Demons, the narrative of La Chinoise is minimal, a hanger on which Godard builds a series of political discussions. Via monologues delivered by the main characters directly to camera, interrupted by Brechtian cutaways to still photographs, intrusions by the director, and even shots of the clapper board and markings denoting the points of edit, we learn of the diverse backgrounds of each of the characters and their motivations for becoming associated with the movement. The students’ time is spent discussing their political ideology (which, it turns out, is plural – various points of fracture and disagreement appearing through their discussions with one another), acting out political skits that satirise topics such as the war in Vietnam, listening to lectures delivered by one another (and by another visiting student, Omar), and listening to a shortwave radio which is tuned to Radio Peking and on which plays a song by Claude Channes, ‘Mao-Mao’, that was written and recorded for use in the film and whose poppy tune is accompanied by lyrics which (ironically?) praises the Little Red Book as the object ‘that makes everything move’. The use of the pop song subtly suggests Maoism is, for these characters, a ‘fad’: revolution is fashionable, a pop culture event. Veronique is committed to this ideology in a manner that makes her different to the other members of the group, however: she is willing to commit murder and promote violence, though ultimately she bodges her plans despite her cold rationalistic approach to planning her assassination attempt. Carrying some loose similarities with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1872 novel Demons, the narrative of La Chinoise is minimal, a hanger on which Godard builds a series of political discussions. Via monologues delivered by the main characters directly to camera, interrupted by Brechtian cutaways to still photographs, intrusions by the director, and even shots of the clapper board and markings denoting the points of edit, we learn of the diverse backgrounds of each of the characters and their motivations for becoming associated with the movement. The students’ time is spent discussing their political ideology (which, it turns out, is plural – various points of fracture and disagreement appearing through their discussions with one another), acting out political skits that satirise topics such as the war in Vietnam, listening to lectures delivered by one another (and by another visiting student, Omar), and listening to a shortwave radio which is tuned to Radio Peking and on which plays a song by Claude Channes, ‘Mao-Mao’, that was written and recorded for use in the film and whose poppy tune is accompanied by lyrics which (ironically?) praises the Little Red Book as the object ‘that makes everything move’. The use of the pop song subtly suggests Maoism is, for these characters, a ‘fad’: revolution is fashionable, a pop culture event. Veronique is committed to this ideology in a manner that makes her different to the other members of the group, however: she is willing to commit murder and promote violence, though ultimately she bodges her plans despite her cold rationalistic approach to planning her assassination attempt.

Video

The film is presented in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio; the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 96:18 mins. The film is presented in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio; the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 96:18 mins.

La Chinoise was shot in 35mm, on Eastman Color stock. Colours in this presentation are commensurate with the qualities of that stock, with vivid primary colours (especially reds and yellows) that display a strong sense of consistency. An excellent level of fine detail is present throughout the picture, including in close-ups. Contrast levels are very pleasing too, with balanced and rich midtones, even highlights and deep shadows. Little to no damage is present, and the encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. The result is a very pleasing, consistent and filmlike presentation of the picture. Some full-size screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented, in French, via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is deep and rich, with good range. Optional English subtitles are included, and these are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with James Quandt. Quandt’s commentary track is closely scripted and analytical, helping enormously to help clarify this deeply oblique picture. Quandt asks ‘Is the film satire or propaganda?’ and he explores the film’s relationship with Godard’s other pictures. It’s an excellent, very thorough track. - Interviews: Michel Semeniako (38:24); Charles Bitsch (18:59); Jean-Claude Sussfeld (17:36). Semeniako, who plays Henri in the film, reflects on his first meeting with Godard and how he came to be involved in the picture. He talks about Godard’s approach to directing and reflects on the director’s politics and preoccupation with language. The assistant director on La Chinoise, Charles Bitsch talks about how he came to be associated with Godard. Bitsch discusses his approach to the craft of filmmaking and his relationship with Godard. Sussefeld, the second assistant director, suggests that Godard was more like ‘a student preparing his thesis or a teacher preparing a lesson’ than a film director, surrounding himself with books and planning his activities very thoroughly. He says that Godard wasn’t very approachable, and the two would lunch together without saying a word; and Godard would transition from ‘being very taciturn’ to making jokes that were ‘very dark and individual’. The interviews are in French, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Denitza Bantcheva on La Chinoise’ (18:43). Bantcheva, the author of the 2011 book L’Age d’or du cinema europeen, reflects on the position of La Chinoise within the career of Godard, foregrounding the film’s ambivalence towards the Maoist students. She argues that Godard depicts the students with sympathy but is critical or satirical in his representation of their ideology. She highlights the ideological naivete of Veronique, in particular. Bantcheva speaks in French; the interview is accompanied by optional English subtitles. - Behind-the-Scenes TV Report (10:00). Footage from the production of the film is presented her, prefaced by an interview with Godard. This archival footage is in rough shape but is fascinating. French, with optional English subtitles. - Venice Film Festival Press Conference (2:22). A brief segment from a current affairs programme contains some behind the scenes footage of the production and an interview with Godard in which he expresses his frustration with conventional methods of storytelling in cinema. French, with optional English subtitles. - Trailer (2:14).

Overall

La Chinoise struggled to find distribution in American owing to its apparently incendiary content, though Godard’s treatment of the Maoist ideology/ies (despite their superficial unity, as the film progresses it's increasingly clear that amongst the students, there is a plurality of interpretations of Maoist theory) of his characters is more ironic than the film’s reputation might suggest. Godard later suggested to Andrew Sarris that his association with Marxist rhetoric was only intended as ‘a provocation’ in the sense that his pictures mixed Marx with Coca-Cola – essentially treating political ideology as a ‘brand’. (In this sense, Godard could be said to have anticipated the fundamental corruption of political rhetoric in the Twenty-First Century; choice of political allegiance has always been tribalistic but has become increasingly allied with, and indistinct from, commercial branding.) Within the confines of the small apartment in which the five students meet and dialogue with one another, they experience an ideological feedback loop which leads to an escalation of Veronique’s rhetoric – ultimately building to an espousal of violence which is followed by a botched assassination. In telling this story, Godard employs a number of devices intended to provoke a Brechtian alienation of the audience from the text, from intertitles in vivid primary colours to shots which include the clapper board and the X marks denoting points of edit. La Chinoise struggled to find distribution in American owing to its apparently incendiary content, though Godard’s treatment of the Maoist ideology/ies (despite their superficial unity, as the film progresses it's increasingly clear that amongst the students, there is a plurality of interpretations of Maoist theory) of his characters is more ironic than the film’s reputation might suggest. Godard later suggested to Andrew Sarris that his association with Marxist rhetoric was only intended as ‘a provocation’ in the sense that his pictures mixed Marx with Coca-Cola – essentially treating political ideology as a ‘brand’. (In this sense, Godard could be said to have anticipated the fundamental corruption of political rhetoric in the Twenty-First Century; choice of political allegiance has always been tribalistic but has become increasingly allied with, and indistinct from, commercial branding.) Within the confines of the small apartment in which the five students meet and dialogue with one another, they experience an ideological feedback loop which leads to an escalation of Veronique’s rhetoric – ultimately building to an espousal of violence which is followed by a botched assassination. In telling this story, Godard employs a number of devices intended to provoke a Brechtian alienation of the audience from the text, from intertitles in vivid primary colours to shots which include the clapper board and the X marks denoting points of edit.

It’s a deliberately difficult film to like though an easy film to admire, and Arrow’s Blu-ray release of La Chinoise contains an excellent presentation of the film which showcases the primary colours of the Eastman Color stock on which the picture was shot. A pivotal film in the director of its career, La Chinoise is represented very well on this release, the pleasing presentation of the main feature being accompanied by some very good contextual material. References: Ling, Alex, 2013: Badiou and Cinema. Edinburgh University Press Click the screengrabs to enlarge:

|

|||||

|