|

|

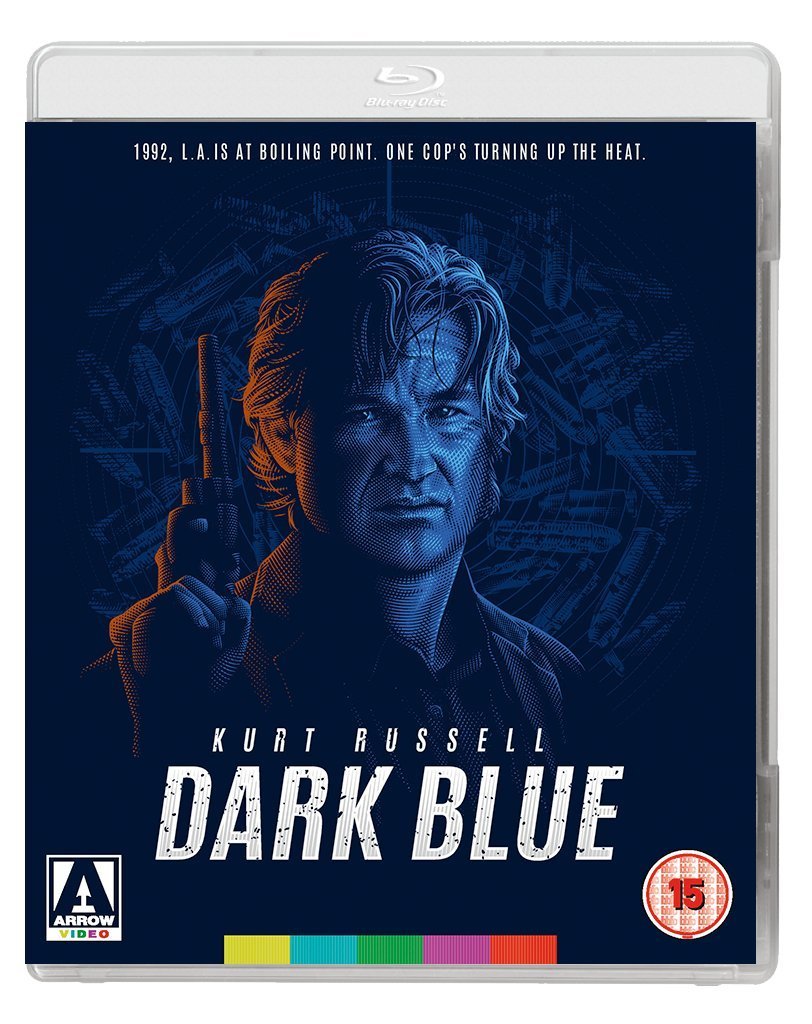

Dark Blue (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th May 2018). |

|

The Film

Dark Blue (Ron Shelton, 2002) Dark Blue (Ron Shelton, 2002)

One year after the beating of Rodney King by four members of the LAPD was caught on video, members of LAPD’s Special Investigation Squad Sgt Eldon Perry (Kurt Russell) and his protégé Bobby Keough (Scott Speedman) are awaiting the results of a hearing into Keough’s shooting of a black suspect, Robertson. Keough is acquitted: the shooting is recorded as justified. Perry and Keough’s boss, Jack Van Meter (Brendan Gleeson), is delighted. However, senior police official Arthur Holland (Ving Rhames) is dissatisfied, telling his assistant Beth (Michael Michele) that he believes Perry shot Robertson, and that both Perry and Keough have perjured themselves. Unbeknownst to Holland, Beth is involved in a purely sexual relationship with Keough; the pair do not know one another’s surnames. Keough is therefore unaware that Beth works for Holland, and Beth is similarly unaware that her lover is the man being investigated for the shooting of Robertson. Meanwhile, Perry’s relationship with his wife Sally (Lolita Davidovich) is fractious, Sally resenting Perry’s drinking, his bravado and his utter dedication to his job. Meanwhile, a pair of robbers – one, Orchard (Kurupt), black and the other, Sidwell (Dash Mihok), white – hold up a convenience store owned by Henry Kim (Dana Lee). They crack a safe in a room above the store, leaving with a large sum of cash. On their way out, they shoot and kill four people, including an off-duty LAPD dispatcher, wounding a fifth, Mr Lewis (Wayne A King, Sr), by shooting him in the throat.  Van Meter asks Perry and Keough to investigate the convenience store robbery. However, it transpires that Van Meter orchestrated the robber, commissioning two of his supergrasses – Orchard and Sidwell – to carry it out. Perry and Keough are unaware of this, though through their investigation they discover that Kim isn’t just the owner of a convenience store: he also owns a strip club from which the dancers are prostituted. As Perry is told by a young street hood, ‘He [Kim] got game’. Van Meter asks Perry and Keough to investigate the convenience store robbery. However, it transpires that Van Meter orchestrated the robber, commissioning two of his supergrasses – Orchard and Sidwell – to carry it out. Perry and Keough are unaware of this, though through their investigation they discover that Kim isn’t just the owner of a convenience store: he also owns a strip club from which the dancers are prostituted. As Perry is told by a young street hood, ‘He [Kim] got game’.

Holland refuses to sign off on Keough’s acquittal, and Van Meter takes this as a declaration of war – which it is. Holland plans to rise through the ranks and become LA’s first black police chief. In response to Holland’s actions, Van Meter orders Perry and Keough to deliver to Holland’s office an envelope which, Keough discovers to his dismay, contains photographs of Holland in flagrante with Beth. Perry and Keough continue to investigate the robbery and discover that they have two suspects, one black and the other white. Perry realises that this must be the only ‘salt and pepper’ team he knows: Orchard and Sidwell. He and Keough approach Van Meter with this information but Van Meter shoots them down, accusing Perry of being way off target and ordering him to frame two other suspects for the crime. However, after Perry and Keough leave his office, Van Meter sets a trap for Perry, calling Orchard and Sidwell and telling them that Perry is on his way to their house. Perry is smarter than Van Meter thinks, though, and realises that a trap has been set for him. However, Keough and Beth are on their way to Orchard and Sidwell’s house too, and seem about to walk into the trap Van Meter set for Perry. Meanwhile, the four officers in the Rodney King case are acquitted, and rioting begins to erupt on the streets of the city.  Written by David Ayer and going into production after the success of Antoine Fuqua’s Training Day (2001), which Ayer also wrote, Dark Blue contains some strong similarities with Fuqua’s film in its focus on the relationship between a seasoned, cynical older cop (who may or may not be corrupt) and his naïve rookie partner. However, truth be told, this is a recurring paradigm in stories about police officers and isn’t simply a characteristic of Ayer’s writing: similar relationships can be found in Richard Fleischer’s The New Centurions (1972, from Joseph Wambaugh’s novel) and Joe Carnahan’s roughly contemporaneous Narc (2002), to cite but two examples, not to mention numerous television cop shows of the 1980s and 1990s. Written by David Ayer and going into production after the success of Antoine Fuqua’s Training Day (2001), which Ayer also wrote, Dark Blue contains some strong similarities with Fuqua’s film in its focus on the relationship between a seasoned, cynical older cop (who may or may not be corrupt) and his naïve rookie partner. However, truth be told, this is a recurring paradigm in stories about police officers and isn’t simply a characteristic of Ayer’s writing: similar relationships can be found in Richard Fleischer’s The New Centurions (1972, from Joseph Wambaugh’s novel) and Joe Carnahan’s roughly contemporaneous Narc (2002), to cite but two examples, not to mention numerous television cop shows of the 1980s and 1990s.

Dark Blue originated in an unproduced screenplay by James Ellroy entitled ‘The Plague Season’. Ellroy’s screenplay had been circulating for almost a decade before the project passed into the hands of Ayer; Ellroy’s vision for ‘The Plague Season’ was to set the story during the Watts riots as a means of commenting upon the then-recent 1992 Los Angeles riots. The critical success of Curtis Hanson’s adaptation of Ellroy’s novel L.A. Confidential in 1997 resulted in film production companies considering the cinematic potential of Ellroy’s work and, more generally, his approach to the crime genre. However, Ellroy’s script for ‘The Plague Season’ was reputedly without dialogue, and in 1998 producer Caldecott Chubb hired David Ayer to flesh the script out; after seeing Ayer’s rewrite, Ellroy demanded he not be credited with writing the screenplay, and instead Ellroy received a ‘story by’ credit. Aside from updating the story and reducing the number of subplots in order to make the script less ‘novelistic’, Ayer ‘consolidated characters’ and ‘changed Holland’s assistant from a male to a female. She became Michael Michele’s character’; he also ‘made Bobby Keough […] younger. It [the role] had been skewed to a 40-plus man and I felt that a guy at that age would know the ropes already and wouldn’t be as susceptible to Eldon Perry’s magic’ (Ayer, quoted in Topel, 2003). Ayer also admitted to making Perry less ‘harsh, misogynistic, racist, [and] brutal’ (Ayer, quoted in ibid.). One can imagine Ellroy’s discontent with Holland’s holier-than-thou attitude and Perry’s act of redemption in the film’s final sequences.  Films such as those mentioned above, in which a young rookie cop is paired with a more seasoned partner/mentor, often focus on ethnic and cultural divisions; this is a recurring thematic motif in cop pictures probably thanks to ongoing rifts in American society between lawlessness and law enforcement – which, in the rhetoric of news media and the films, is often coded as a black/white issue, the police being represented as an agent of white America suppressing ‘black’ criminality. (In Dark Blue, though various characters note the unique nature of the Orchard and Sidwell partnership as being a ‘salt and pepper’ team, Sidwell adopts the street lingo and swagger of the African American street hoods shown in the film; ironically, as if to reinforce Sidwell’s ethnic outsider status amongst the street gangs, he is beaten to death at the climax, during the LA riots, by a group of black men who drag him out of his car and kill him simply for the fact that he is white; the imagery presumably deliberately recalls the video footage of the ‘LA Four’ and their attack upon trucker Reginald Denny.) Such films often explore what is nowadays labelled ‘institutional racism’ – though it’s really just pure bigotry that bubbles to the surface. Within Dark Blue, this sense of black v. white is narrativised through the conflict between Holland and Van Meter, who are roughly equals of rank within the police force. At one point, Van Meter and Holland encounter one another in a lift; this scene offers the only dialogue that these two characters share. They talk around the issue, Van Meter speaking with Holland about boats, until Holland confronts Van Meter directly: ‘I’m ready for you’, he says, ‘We can handle this like gentlemen or we can get into some nigger shit. So you go ahead and do whatever it is you plan to do’. With this, Van Meter’s bigotry, kept in check throughout the rest of the film, explodes to the surface: ‘Oh, I plan to, nigger’, he says, spitting the epithet out bitterly. The use of language in this scene teases out the underlying racism of Van Meter’s position – which influences the manner in which he responds to claims that his officers have acted above the law in response to ‘black’ crime. Films such as those mentioned above, in which a young rookie cop is paired with a more seasoned partner/mentor, often focus on ethnic and cultural divisions; this is a recurring thematic motif in cop pictures probably thanks to ongoing rifts in American society between lawlessness and law enforcement – which, in the rhetoric of news media and the films, is often coded as a black/white issue, the police being represented as an agent of white America suppressing ‘black’ criminality. (In Dark Blue, though various characters note the unique nature of the Orchard and Sidwell partnership as being a ‘salt and pepper’ team, Sidwell adopts the street lingo and swagger of the African American street hoods shown in the film; ironically, as if to reinforce Sidwell’s ethnic outsider status amongst the street gangs, he is beaten to death at the climax, during the LA riots, by a group of black men who drag him out of his car and kill him simply for the fact that he is white; the imagery presumably deliberately recalls the video footage of the ‘LA Four’ and their attack upon trucker Reginald Denny.) Such films often explore what is nowadays labelled ‘institutional racism’ – though it’s really just pure bigotry that bubbles to the surface. Within Dark Blue, this sense of black v. white is narrativised through the conflict between Holland and Van Meter, who are roughly equals of rank within the police force. At one point, Van Meter and Holland encounter one another in a lift; this scene offers the only dialogue that these two characters share. They talk around the issue, Van Meter speaking with Holland about boats, until Holland confronts Van Meter directly: ‘I’m ready for you’, he says, ‘We can handle this like gentlemen or we can get into some nigger shit. So you go ahead and do whatever it is you plan to do’. With this, Van Meter’s bigotry, kept in check throughout the rest of the film, explodes to the surface: ‘Oh, I plan to, nigger’, he says, spitting the epithet out bitterly. The use of language in this scene teases out the underlying racism of Van Meter’s position – which influences the manner in which he responds to claims that his officers have acted above the law in response to ‘black’ crime.

Dark Blue foregrounds the ethnic conflict at the heart of most, if not all, US cop films by setting its narrative in the immediate aftermath of the Rodney King incident, as the city awaits the verdict passed on the four police officers accused of beating King; of course, as the audience knows, these four officers will be acquitted and Los Angeles will inevitably erupt into the violence of the 1992 riots. Only Eldon Perry seems to have the forethought to realise that this violence is inevitable, telling Keough that the police department cannot, and will not, indict the four police officers for the beating of King, and that their acquittal will result in an eruption of violence to equal the race riots of the 1960s. Dark Blue juxtaposes the King incident with the hearing that follows Keough’s shooting of Robertson, an act that has taken place before the film’s narrative begins. Keough is acquitted, the head of the panel (Jonathan Banks) visiting Keough, Perry and Van Meter after the hearing for a chat and joke, an act which suggests an ‘old boy’s network within the LAPD; Keough’s acquittal anticipates the acquittal of the four cops in the Rodney King case. However, Keough’s acquittal angers Holland, who is on the panel, as Holland knows that Keough didn’t shoot Robertson but is taking the fall for Perry; Keough and Perry have perjured themselves throughout the hearing. In response, Holland refuses to sign the documents pertaining to Keough’s acquittal, leading Van Meter to try to blackmail Holland with photographs showing the married Holland in flagrante delicto with his assistant Beth – who also happens to be Keough’s lover. (Keough’s relationship with Beth seems obviously inserted to prove to the audience that though Van Meter and possible Perry may harbour racist sentiments, Keough is a relative innocent – unprejudiced and involved in a romantic affair with a black woman.)  Where the opening sequences of the film frame Perry as a corrupting influence on the life of his protégé Keough, as the narrative progresses the script begins to paint Perry as a tragic figure. Perry comes from a line of police officers, and at the end of the film he recollects his grandfather’s role as a sheriff during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, and Perry also recounts a personal memory from the Watts riots, during which Perry’s father took delight in shooting black looters. Perry admits that ‘I was raised up to be a gunfighter by a family of gunfighters’. Like many police officers, Perry believes that his profession has been stripped of the tactics that are proven to work and must ‘make do’ with methods that can have more disastrous consequences. ‘When they got rid of the chokehold, it left us with the stun gun and the baton’, Keough tells Perry, ‘The chokehold saved lives but nobody ever got elected saying that. They don’t give those guys [patrol officers] enough cars, radios, equipment or live bodies to man the watches, and then they take away the tactics that work and they indict them [the officers] for using the approved tactics that don’t’. Perry is also manoeuvred by his boss, Van Meter, who has one eye on internal politics and the other on his own wallet – hiring two supergrasses, Orchard and Sidwell, to stage robberies in order to line his pockets. (Van Meter selects Kim as a target owing to Kim’s association with prostitution, this presumably allowing Van Meter to justify to himself his commissioning of the robbery.) As Perry becomes increasingly aware of just how crooked Van Meter is, Van Meter sets Perry up to be killed by Orchard and Sidwell, and event that has tragic consequences for Keough. This betrayal by Van Meter, which Van Meter orchestrates with hardly a second thought, precipitates Perry’s redemption. Where the opening sequences of the film frame Perry as a corrupting influence on the life of his protégé Keough, as the narrative progresses the script begins to paint Perry as a tragic figure. Perry comes from a line of police officers, and at the end of the film he recollects his grandfather’s role as a sheriff during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, and Perry also recounts a personal memory from the Watts riots, during which Perry’s father took delight in shooting black looters. Perry admits that ‘I was raised up to be a gunfighter by a family of gunfighters’. Like many police officers, Perry believes that his profession has been stripped of the tactics that are proven to work and must ‘make do’ with methods that can have more disastrous consequences. ‘When they got rid of the chokehold, it left us with the stun gun and the baton’, Keough tells Perry, ‘The chokehold saved lives but nobody ever got elected saying that. They don’t give those guys [patrol officers] enough cars, radios, equipment or live bodies to man the watches, and then they take away the tactics that work and they indict them [the officers] for using the approved tactics that don’t’. Perry is also manoeuvred by his boss, Van Meter, who has one eye on internal politics and the other on his own wallet – hiring two supergrasses, Orchard and Sidwell, to stage robberies in order to line his pockets. (Van Meter selects Kim as a target owing to Kim’s association with prostitution, this presumably allowing Van Meter to justify to himself his commissioning of the robbery.) As Perry becomes increasingly aware of just how crooked Van Meter is, Van Meter sets Perry up to be killed by Orchard and Sidwell, and event that has tragic consequences for Keough. This betrayal by Van Meter, which Van Meter orchestrates with hardly a second thought, precipitates Perry’s redemption.

Holland’s narrative is as interesting as that of Keough and Perry, though for the most part Holland is relegated to the background. Openly critical of the board’s acquittal of Keough in the Robertson shooting, Holland aspires to be the city’s first African American police chief and is willing to confront head-on the endemic racism within the LAPD. In Holland’s story, Dark Blue bears comparison with Charles Burnett’s The Glass Shield (1994). The Glass Shield was made in 1994, two years after the LA riots, and is one of the few cop films to focus on a black police officer, a new recruit who uncovers a web of corruption within his police department. Where Dark Blue, and for that matter Training Day, are very ‘Hollywood’ in their structure and approach, Burnett’s picture is much more low-key. However, both films pit the new against the old; establishing a dialectic between tradition and ‘modern thinking’. ‘You boys are heroes’, Van Meter tells Perry and Keough at one point in the film, ‘I like heroes. A simple idea, really. You got your villain; you got your hero. The “modern-thinking” part is complicated, but it always comes down to that. You know, those who victimise were once victims, all that stuff they teach you in college. It’s sad. It’s probably even true. It really doesn’t matter. Everybody’s got a sad story. Who gives a shit?’

Video

Uncut and running for 117:59 mins, the film takes up just over 25Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.39:1, Dark Blue’s 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Shot on 35mm colour stock (though some video footage is inserted here and there to suggest a theme of surveillance), Dark Blue gets a pleasing presentation on this disc. Fine detail is often very strong, especially in close-ups. (There are a few close-ups of a booze-sodden Eldon Perry in which we can almost count the pores in Kurt Russell’s skin.) However, it’s not consistent and other shots seems noticeably softer, probably owing to the qualities of the different lenses used during the production. As one might expect for a picture set in Los Angeles, the palette is for the most part dominated by warm hues, though the light is noticeably cold in the hotel room in which Perry seeks solace after his wife leaves him; this may have been a conscious decision to symbolise Perry’s isolation and despair, but it’s a jarring contrast with the bulk of the film. Contrast levels are very good, the harsh shadows of the LA sun being conveyed effectively through carefully balanced and richly defined midtones and deep shadows. The encode retains the structure of 35mm film, and it’s a pleasingly filmlike viewing experience. However, there does seem to be some noticeable haloing/edge enhancement in some scenes – nothing too drastic or detrimental but present nonetheless. Uncut and running for 117:59 mins, the film takes up just over 25Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.39:1, Dark Blue’s 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Shot on 35mm colour stock (though some video footage is inserted here and there to suggest a theme of surveillance), Dark Blue gets a pleasing presentation on this disc. Fine detail is often very strong, especially in close-ups. (There are a few close-ups of a booze-sodden Eldon Perry in which we can almost count the pores in Kurt Russell’s skin.) However, it’s not consistent and other shots seems noticeably softer, probably owing to the qualities of the different lenses used during the production. As one might expect for a picture set in Los Angeles, the palette is for the most part dominated by warm hues, though the light is noticeably cold in the hotel room in which Perry seeks solace after his wife leaves him; this may have been a conscious decision to symbolise Perry’s isolation and despair, but it’s a jarring contrast with the bulk of the film. Contrast levels are very good, the harsh shadows of the LA sun being conveyed effectively through carefully balanced and richly defined midtones and deep shadows. The encode retains the structure of 35mm film, and it’s a pleasingly filmlike viewing experience. However, there does seem to be some noticeable haloing/edge enhancement in some scenes – nothing too drastic or detrimental but present nonetheless.

Please see the bottom of this review for full-sized screengrabs (click to enlarge).

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. This is rich and deep, dialogue being clear throughout, and has excellent range. It comes alive in the more action-oriented scenes, particularly towards the climax, with atmospheric sound separation. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc ports over the extras from the film’s 2003 DVD release, including: The disc ports over the extras from the film’s 2003 DVD release, including:

- An audio commentary with director Ron Shelton. Shelton reflects on the production of the film, discussing the difficulties he and his crew faced in shooting the picture on location and with a relatively modest budget, at least by Hollywood standards. He also talks about the ways in which the film’s narrative intersects with social issues and the controversies of the LAPD. - ‘Code Blue’ (18:20). This archival featurette has input from Michael Michele, Kurt Russell, Ving Rhames, producer Caldecot Chubb, Ron Shelton and David Ayer. The participants reflect on the film’s depiction of the LA riots, and they talk about the origins of the picture in James Ellroy’s spec script. Shelton says that one of his aims was to ‘humanise’ the character of Perry, depicting him as ‘a character wrestling with the devil and losing’. Interviews with the participants are intercut with behind-the-scenes footage and clips from the film. - ‘By the Book’ (7:16). This featurette focuses on the film’s aesthetic, and features input from Shelton, art director Tom Taylor, production designer Dennis Washington and costume designer Kathryn Morrison. The participants talk about the search for authentic-looking locations and the challenges faced in acquiring these locations and making them fit for purpose (and safe). They also discuss how the riots were staged convincingly, Taylor joking that ‘the original riots had a much bigger budget than we did’. Morrison discusses the search for authenticity in terms of the costumes too. - ‘Necessary Force’ (6:55). Shelton and Russell discuss how they sought to make the film’s depiction of policework authentic, aided by technical advisor Bob Souza, an LAPD veteran of 22 years. Souza talks about the work of the SIS and their status as ‘frontline’ officers – which often necessitates hardline tactics. - Interviews: Kurt Russell (11:37); Scott Speedman (7:39); Michael Michele (9:27); Ron Shelton (13:35). These interviews are culled from the film’s original EPK and see the cast reflecting on their performances, their roles and what attracted them to the project, and Shelton discussing his intentions for the film. - Trailer (1:58). - TV Spots (1:45).

Overall

Dark Blue was at the vanguard of a series of films and television series that looked sideways towards the Rampart scandal, alongside The Shield (2002-8) and Southland (2009-13), films such as David Ayer’s Street Kings (2008) and End of Watch (2012), and, more directly, Rampart (Oren Moverman, 2011). Both Rampart and Street Kings featured input from Ellroy, Street Kings being based on a script by Ellroy from the late 1990s entitled ‘The Night Watchman’. Dark Blue was at the vanguard of a series of films and television series that looked sideways towards the Rampart scandal, alongside The Shield (2002-8) and Southland (2009-13), films such as David Ayer’s Street Kings (2008) and End of Watch (2012), and, more directly, Rampart (Oren Moverman, 2011). Both Rampart and Street Kings featured input from Ellroy, Street Kings being based on a script by Ellroy from the late 1990s entitled ‘The Night Watchman’.

It would be interesting to have access to Ellroy’s original script, as though updating the story from the Watts riots to the post-Rodney King LA riots ‘works’, other elements that would seem to have been added after Ellroy’s departure from the project feel very archetypally ‘Hollywood’ in a way that results in a film which is often deeply clichéd. Despite these clichés, however, the film is held together, for the most part, by Kurt Russell’s performance as Perry. At the time, the role was something of a departure for Russell, whose characters to that point had always been fairly sympathetic. Nevertheless, even much of Perry’s life is by-the-numbers – especially the alienated wife who eventually musters up the courage to leave him, the use of alcohol to numb his moral sense, and who tells Perry before leaving him that ‘I have watched you descend into hell, and I have been waiting for you to come back. Apparently, you don’t want to’. Dark Blue is an interesting film, not entirely successful and in some ways compromised; but nevertheless like the other Rampart-influenced pictures of the late 1990s and early 2000s it has a sense of reality and engagement with the world that is an antidote to the current vogue for superhero pictures – which arguably confront very similar issues about social division, unfettered power and corruption (for example, 2016’s Captain America: Civil War) but within the framework of the fantastical. Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation is a big improvement over Dark Blue’s previous DVD releases. Some edge enhancement seems to be present but it’s not too detrimental and for the most part, the presentation is very organic and filmlike. Detail and contrast are hugely improved over the DVD releases. The disc also ports over the contextual material from the film’s DVD/s. It would have been nice to have seen some retrospective content, perhaps focusing on Ellroy’s association with the picture – something which is only touched on briefly in the other material – but nevertheless there’s a solid range of contextual material on this disc, which comes with a solid recommendation. References: Topel, Fred, 2003: ‘David Ayer Talks Training Day and Dark Blue’. Screenwriter’s Monthly Magazine (April, 2003) Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|