|

|

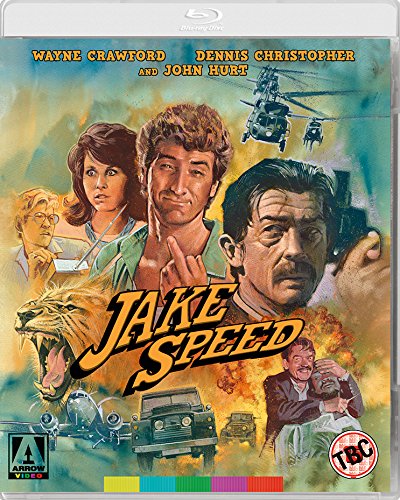

Jake Speed (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Video Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th June 2018). |

|

The Film

Jake Speed (Andrew Lane, 1986) Jake Speed (Andrew Lane, 1986)

In Paris, American tourist Maureen (Becca C Ashley) and her friend are abducted. In America, Maureen’s family feel disempowered by the news of Maureen’s abduction. Maureen’s grandfather (Leon Ames) suggests they should seek the help of Jake Speed, the hero of the paperback novels he reads. Grandpa is ridiculed by the rest of the family, but soon Maureen’s sister Margaret (Karen Kopins) receives a note telling her to visit a seedy dive on the San Pedro docks. There she meets Desmond Floyd (Dennis Christopher), who claims to be the assistant of the real Jake Speed (Wayne Crawford). Des tells Margaret that Maureen was kidnapped by an ‘international gang of white slavers’ and is now in Africa. Jake Speed will assist Margaret in finding Maureen, but Margaret must meet him in Africa. Margaret arrives in Africa to find the region on the brink of revolution. However, Speed is willing to work for free: he takes on jobs in order to provide material for the novels based on his escapades, which are written by Des under the pen-name ‘Reno Melon’ (‘His favourite town, my favourite fruit’, Des tells Margaret). However, Margaret begins to doubt the intentions of Speed and Des. Fleeing from them, she ends up in the hands of white slavers Sidney (John Hurt) and his brother Maurice (Roy London), who are in the midst of brokering a deal with two visiting Turks (Frantz Dobrowsky and Will Bernard) in exchange for Maureen and her friend.  Jake Speed was cut from the same cloth as a number of post-Raiders of the Lost Ark (Spielberg, 1981) films that looked backwards to Saturday action serials with their often outrageous stereotypes and episodic narratives. These films include Romancing the Stone (Robert Zemeckis, 1984), King Solomon’s Mines (J Lee Thompson, 1985), High Road to China (Brian G Hutton, 1983) with Tom Selleck, and Firewalker (also J Lee Thompson, 1986) with Chuck Norris and Lou Gossett Jr. They also encompassed movies in which characters from literature or television were brought to life, such as John Hough’s Biggles: Adventures in Time (1986), Willard Huyck’s Howard the Duck (1986) and Gary Goddard’s Masters of the Universe (1987). These films juxtaposed the exciting world of high fiction with the ‘real’ world, often featuring portal fantasy-like plots in which characters travel from the ‘real’ world to the exciting fantasy world, and deliriously metafictional scenes in which other characters express disbelief at the appearance of characters they believed to be fictional. (This subtype of films, popular in the 1980s, was of course parodied heavily in John McTiernan’s wonderful The Last Action Hero in 1993.) Jake Speed was cut from the same cloth as a number of post-Raiders of the Lost Ark (Spielberg, 1981) films that looked backwards to Saturday action serials with their often outrageous stereotypes and episodic narratives. These films include Romancing the Stone (Robert Zemeckis, 1984), King Solomon’s Mines (J Lee Thompson, 1985), High Road to China (Brian G Hutton, 1983) with Tom Selleck, and Firewalker (also J Lee Thompson, 1986) with Chuck Norris and Lou Gossett Jr. They also encompassed movies in which characters from literature or television were brought to life, such as John Hough’s Biggles: Adventures in Time (1986), Willard Huyck’s Howard the Duck (1986) and Gary Goddard’s Masters of the Universe (1987). These films juxtaposed the exciting world of high fiction with the ‘real’ world, often featuring portal fantasy-like plots in which characters travel from the ‘real’ world to the exciting fantasy world, and deliriously metafictional scenes in which other characters express disbelief at the appearance of characters they believed to be fictional. (This subtype of films, popular in the 1980s, was of course parodied heavily in John McTiernan’s wonderful The Last Action Hero in 1993.)

Like those films, Jake Speed plays with the fictional status of its hero. After Maureen is kidnapped, Margaret’s grandfather suggests contacting Jake Speed to help find Maureen. ‘You want action, not talk’, he says, ‘Jake Speed’s the man for the job’. When asked who Jake Speed is, Margaret’s grandfather asserts that, ‘They [Speed and Des] defeat evil where it exists’. However, it is soon revealed that Jake Speed is a character in the hardboiled books that Margaret’s grandfather reads, which are similar to the novels of David Dodge (Plunder of the Sun, 1949) or John Lange/Michael Crichton (Zero Cool, 1969). Grandpa is ridiculed by the rest of the family, but Margaret’s friend observes that ‘At least your grandpa believes in someone […] Who are our heroes? No-one’. When Margaret meets Des, Jake Speed’s assistant, in a dingy pub on the San Pedro docks, she is transported into another, fantastical world; her journey via plane from America to Africa functions like a portal from the ‘real’ world to its fantastical opposite. For Margaret, this is the first taste of adventure in her otherwise ‘safe’ life. ‘Can you handle an adventure’, Speed asks her upon their first meeting. ‘I’ve never had one before’, Margaret says, questioning ‘Why do you need me to go with you?’ ‘Sometimes you do things the hard way’, Speed responds. ‘Why?’, Margaret asks. ‘Reads better’, Speed tells her. For much of the film, Margaret is left wondering whether Speed and Des are the ‘real’ Speed and Des, or if they are charlatans or perhaps deluded imposters.  The set-up is highly reminiscent of Pierre Morel’s recent Taken (2008): an American girl, and her friend, are kidnapped in Paris by white slavers, and the search for her, conducted by a grieving relative, results in high adventure. Like Taken, Jake Speed is driven by a dualistic opposition between America and the rest of the world. The kidnapping takes place in Paris, but Maureen and her friend are transported by white slavers to Africa, where they are sold by the sleazy Englishman Sidney (played wonderfully by John Hurt) to a pair of Turks. This journey from the ‘civilised’ world to its ‘opposite’ is communicated through the iconography of Margaret’s journey to Africa, communicated within a montage that is played for laughs. Margaret begins on a passenger plane, then finds herself on a smaller plane before spending the final leg of her journey on what looks like a converted military transport vehicle in which the passengers are packed like sardines on seats no different from those found on buses, and travel amid cages filled with livestock – much like the plane seen in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, released the same year. The African country in which the bulk of the action takes place is on the brink of revolution; upon disembarking from her plane, Margaret encounters a man armed with an AK-47. It doesn’t take long for the region to descend into all-out war, gunfire and explosions bursting through the streets as Margaret, Jake and Des take flight from the chaos. Amidst this turmoil, the opportunistic Sidney and his brother Maurice seize their opportunity to make fast money selling kidnapped Caucasian girls to dastardly ‘foreigners’. (In his sales pitch to the two Turks, Sidney first mentions the girls’ tanned skin, then when the buyers don’t jump at the chance to purchase the women, comments, ‘Ah, you want them white’, adding that a few days out of the sun will result in the young women losing their tan.) It’s clear that, as in Taken, the girls are being sold for the sexual gratification of Sidney and Maurice’s clients. Through the actions of Sidney and Maurice, the film offers a veiled critique of the First World’s economic intervention in, and exploitation of, post-colonial countries, and John Hurt invests Sidney with an incredible sense of malicious, racist sleaziness that is combined with the brothers’ penchant for Reagan-era enterprise and valuing of capital over human life. (Sidney is introduced shooting a black servant for a minor lapse in protocol; Maurice enters and chastises Sidney for getting blood on the $10,000 rug.) The set-up is highly reminiscent of Pierre Morel’s recent Taken (2008): an American girl, and her friend, are kidnapped in Paris by white slavers, and the search for her, conducted by a grieving relative, results in high adventure. Like Taken, Jake Speed is driven by a dualistic opposition between America and the rest of the world. The kidnapping takes place in Paris, but Maureen and her friend are transported by white slavers to Africa, where they are sold by the sleazy Englishman Sidney (played wonderfully by John Hurt) to a pair of Turks. This journey from the ‘civilised’ world to its ‘opposite’ is communicated through the iconography of Margaret’s journey to Africa, communicated within a montage that is played for laughs. Margaret begins on a passenger plane, then finds herself on a smaller plane before spending the final leg of her journey on what looks like a converted military transport vehicle in which the passengers are packed like sardines on seats no different from those found on buses, and travel amid cages filled with livestock – much like the plane seen in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, released the same year. The African country in which the bulk of the action takes place is on the brink of revolution; upon disembarking from her plane, Margaret encounters a man armed with an AK-47. It doesn’t take long for the region to descend into all-out war, gunfire and explosions bursting through the streets as Margaret, Jake and Des take flight from the chaos. Amidst this turmoil, the opportunistic Sidney and his brother Maurice seize their opportunity to make fast money selling kidnapped Caucasian girls to dastardly ‘foreigners’. (In his sales pitch to the two Turks, Sidney first mentions the girls’ tanned skin, then when the buyers don’t jump at the chance to purchase the women, comments, ‘Ah, you want them white’, adding that a few days out of the sun will result in the young women losing their tan.) It’s clear that, as in Taken, the girls are being sold for the sexual gratification of Sidney and Maurice’s clients. Through the actions of Sidney and Maurice, the film offers a veiled critique of the First World’s economic intervention in, and exploitation of, post-colonial countries, and John Hurt invests Sidney with an incredible sense of malicious, racist sleaziness that is combined with the brothers’ penchant for Reagan-era enterprise and valuing of capital over human life. (Sidney is introduced shooting a black servant for a minor lapse in protocol; Maurice enters and chastises Sidney for getting blood on the $10,000 rug.)

By contrasting the ‘real’ world with a fantastical world of high adventure, easily defined heroes (‘I’m the last of the real nice guys’, Speed tells Margaret) and outrageous villains, films like Biggles: Adventures in Time, Romancing the Stone and King Solomon’s Mines expressed a nostalgia for a (fictional) period in which ‘good’ and ‘evil’ were clearly delineated, during an era dominated by scandals (for example, the Iran-Contra mess) which seemed to codify government, big business and the law as defined by their involvement in morally dubious enterprises (especially the destabilisation of overseas regimes). Jake Speed confronts this changing sense of morality in its dialogue, when towards the end of the film Sidney delivers a monologue asserting that Speed should ‘Hang it up […] You’re old news. Now, it’s terrorists, bombers, politicians, lawyers, people like me. Everybody’s living off somebody else. Well, don you get it, Jake? It’s our time! You’re too good to be true. You’re history, Jake’. Earlier, Sidney tells Speed that ‘I’m a bad guy, Jake. I do anything I want. I like, I cheat, I steal, I kill [….] I take great pride in never having lived up to anything’. As the narrative progresses, the ‘soft’ PG-rated fantasy established in the film’s early sequences gives way to some unpleasant truths of the real world: the suggestion of sexual slavery; the implications of rape in the dialogue when Sidney holds Margaret hostage as the film nears its climax; the suggestion of torture and sexual sadism when Margaret and Jake are fleeing through Sidney’s base of operations and Jake opens a door onto a very real-looking room of torture, with blood smeared across the walls and various unpleasant-looking implements on the floor. In these scenes, the film opens a window onto the cruelties of the real world, finally moving from the world of recognisable movie violence to something more unpleasant when Sidney takes a helpless black man hostage in front of Speed, holding a knife to his captive’s throat. Speed tries to barter for the man’s life, but Sidney brutally slashes the man’s neck (an act which is thankfully filmed from behind Sidney). It’s a stark moment in which fantasy violence becomes very real, as if to remind viewers of the artifice of movie violence, like the moments of overkill in Paul Verhoeven’s Hollywood films (RoboCop, 1987 and Total Recall, 1990). The viewer might be reminded of Sam Peckinpah’s intentions with the violence in The Wild Bunch, to ‘get people involved in [the violence] so that they are starting to go into the Hollywood television predictable reaction syndrome, and then twist it so that it’s not fun anymore, just a wave of sickness in the gut... It’s ugly, brutalizing and bloody fucking awful [....] And yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement because we’re all violent people’ (Peckinpah, quoted in Weddle, 1994: 334). By contrasting the ‘real’ world with a fantastical world of high adventure, easily defined heroes (‘I’m the last of the real nice guys’, Speed tells Margaret) and outrageous villains, films like Biggles: Adventures in Time, Romancing the Stone and King Solomon’s Mines expressed a nostalgia for a (fictional) period in which ‘good’ and ‘evil’ were clearly delineated, during an era dominated by scandals (for example, the Iran-Contra mess) which seemed to codify government, big business and the law as defined by their involvement in morally dubious enterprises (especially the destabilisation of overseas regimes). Jake Speed confronts this changing sense of morality in its dialogue, when towards the end of the film Sidney delivers a monologue asserting that Speed should ‘Hang it up […] You’re old news. Now, it’s terrorists, bombers, politicians, lawyers, people like me. Everybody’s living off somebody else. Well, don you get it, Jake? It’s our time! You’re too good to be true. You’re history, Jake’. Earlier, Sidney tells Speed that ‘I’m a bad guy, Jake. I do anything I want. I like, I cheat, I steal, I kill [….] I take great pride in never having lived up to anything’. As the narrative progresses, the ‘soft’ PG-rated fantasy established in the film’s early sequences gives way to some unpleasant truths of the real world: the suggestion of sexual slavery; the implications of rape in the dialogue when Sidney holds Margaret hostage as the film nears its climax; the suggestion of torture and sexual sadism when Margaret and Jake are fleeing through Sidney’s base of operations and Jake opens a door onto a very real-looking room of torture, with blood smeared across the walls and various unpleasant-looking implements on the floor. In these scenes, the film opens a window onto the cruelties of the real world, finally moving from the world of recognisable movie violence to something more unpleasant when Sidney takes a helpless black man hostage in front of Speed, holding a knife to his captive’s throat. Speed tries to barter for the man’s life, but Sidney brutally slashes the man’s neck (an act which is thankfully filmed from behind Sidney). It’s a stark moment in which fantasy violence becomes very real, as if to remind viewers of the artifice of movie violence, like the moments of overkill in Paul Verhoeven’s Hollywood films (RoboCop, 1987 and Total Recall, 1990). The viewer might be reminded of Sam Peckinpah’s intentions with the violence in The Wild Bunch, to ‘get people involved in [the violence] so that they are starting to go into the Hollywood television predictable reaction syndrome, and then twist it so that it’s not fun anymore, just a wave of sickness in the gut... It’s ugly, brutalizing and bloody fucking awful [....] And yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement because we’re all violent people’ (Peckinpah, quoted in Weddle, 1994: 334).

Jake Speed has some entertaining action sequences but is curiously paced: there are lulls in action and dialogue, as if some shots have been allowed to play slightly too long in the edit or not enough coverage was sought during production. Nevertheless, the metafictional elements and humour are handled well. (‘If you’re such a big deal, why haven’t they made a movie?’, Margaret asks Speed, to which he responds by saying, ‘Have you ever had to deal with those people?’) As if to further this, confusion of fantasy and reality, a tie-in novel written by ‘Reno Melon’ (the pseudonym under which the books are written in the film itself, the pen-name based, in the words of Des, on ‘his favourite town and my favourite fruit’) was published in 1986 too.

Video

Jake Speed is here presented uncut, with a running time of 104:52 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The source for the presentation isn’t identified by Arrow (though perhaps may be in the booklet accompanying retail copies of the disc), but the digital master was presumably passed on to Arrow by the rights’ holders. Based on the presentation, it seems fair to assume that a positive source was used – most likely an interpositive. Damage is minimal; the level of detail is good and a noticeable improvement on the DVD releases, though there’s a slightly artificial-looking softness that creeps into the image from time to time. Though quite bold in places, contrast levels are for the most part fairly pleasing, with low-light scenes playing pretty well: strong midtones are accompanied by some sharp gradation in the shadows. Highlights are balanced evenly. Colours are mostly natural, but there is a slight red shift that is noticeable in skin tones which often look ‘hot’ beyond the requirements of the narrative. The encode to disc presents no major problems; the structure of 35mm film is present though seems muted in some scenes. It’s a good presentation, a big improvement over what was offered by the DVD format, but there’s some noticeable room for further improvement. Jake Speed is here presented uncut, with a running time of 104:52 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The source for the presentation isn’t identified by Arrow (though perhaps may be in the booklet accompanying retail copies of the disc), but the digital master was presumably passed on to Arrow by the rights’ holders. Based on the presentation, it seems fair to assume that a positive source was used – most likely an interpositive. Damage is minimal; the level of detail is good and a noticeable improvement on the DVD releases, though there’s a slightly artificial-looking softness that creeps into the image from time to time. Though quite bold in places, contrast levels are for the most part fairly pleasing, with low-light scenes playing pretty well: strong midtones are accompanied by some sharp gradation in the shadows. Highlights are balanced evenly. Colours are mostly natural, but there is a slight red shift that is noticeable in skin tones which often look ‘hot’ beyond the requirements of the narrative. The encode to disc presents no major problems; the structure of 35mm film is present though seems muted in some scenes. It’s a good presentation, a big improvement over what was offered by the DVD format, but there’s some noticeable room for further improvement.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 track. This is rich, with good depth and dialogue is clear throughout. The dialogue is mostly in English, though the opening sequence features some French dialogue accompanied by burnt-in English subtitles. Elsewhere, optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included on the disc. These are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Paperback Wishes, Cinematic Dreams: Directing Jake Speed’ (20:54). This new interview features the film’s director (and co-writer) Andrew Lane reflecting on the making of the film. Lane talks about his and Wayne Crawford’s origins in the independent filmmaking sector (the pair wrote Harry Kerwin’s 1977 film Tomcats together). He says their ethos was ‘to work for ourselves, make the movies we wanted to make’. Their ‘business plan’ was to work their way up, making each film ‘a little bit bigger, a little bit better’. Jake Speed, he says, ‘was the natural progression of our careers’ and was ‘the result of a couple of successful movies’ he and Crawford had made together. They signed up with New World Pictures and pitched the film, cognisant that ‘we were small players making smaller movies, in a sense competing with the major studios for shelf space and public awareness of our stories. If you make genre movies, it’s really incumbent upon us to make films’ that have some sort of differentiation from their competition. It’s an interesting interview that shows Lane’s experience in the world of independent filmmaking. - ‘The Hard Way Reads Better: Producing Jake Speed’ (12:00). In another new interview, producer William Fay discusses the film. He reflects on his road to filmmaking, which began with working as a production assistant and then scriptwriter, working his way up to producer. He discusses the budget limitations of Jake Speed in comparison with Raiders of the Lost Ark and Romancing the Stone, which resulted in ‘working with a lot of less experienced crew’ and decisions made to economise ‘and get as much production value on the screen as possible’. Most of the film’s crew were from Africa; the stunt team was Australian; various personnel were from Europe. This interview with Fay is fascinating in terms of providing insight into the difficulties in putting together an independently-made feature during the 1980s.

Overall

Jake Speed is a fun film that is very much of its time. Some elements of the picture are curiously ‘flat’, the dialogue and action sometimes strangely paced. However, the film benefits from a barnstorming performance by John Hurt as the antagonist, and despite the odd lulls in action in the first half of the picture, it comes alive once Hurt’s Sidney enters the story. As the story progresses, the violence evolves from the typical fare expected from 1980s adventure films to more sinister and cruel types of violence, the attempts at metafiction masking a critique of the villains of the day (big business, post-colonial intervention in the developing world) that erupts in the aforementioned monologue by Sidney towards story’s end. Jake Speed is a fun film that is very much of its time. Some elements of the picture are curiously ‘flat’, the dialogue and action sometimes strangely paced. However, the film benefits from a barnstorming performance by John Hurt as the antagonist, and despite the odd lulls in action in the first half of the picture, it comes alive once Hurt’s Sidney enters the story. As the story progresses, the violence evolves from the typical fare expected from 1980s adventure films to more sinister and cruel types of violence, the attempts at metafiction masking a critique of the villains of the day (big business, post-colonial intervention in the developing world) that erupts in the aforementioned monologue by Sidney towards story’s end.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Jake Speed contains a fairly good presentation of the main feature that is an easy step up from the film’s previous home video releases, though there is some room for improvement. The main feature is supported by some interesting contextual material. References: WEDDLE, David, 1994: ‘If They Move... Kill ‘Em!’: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah. New York: Grove Press Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|