|

|

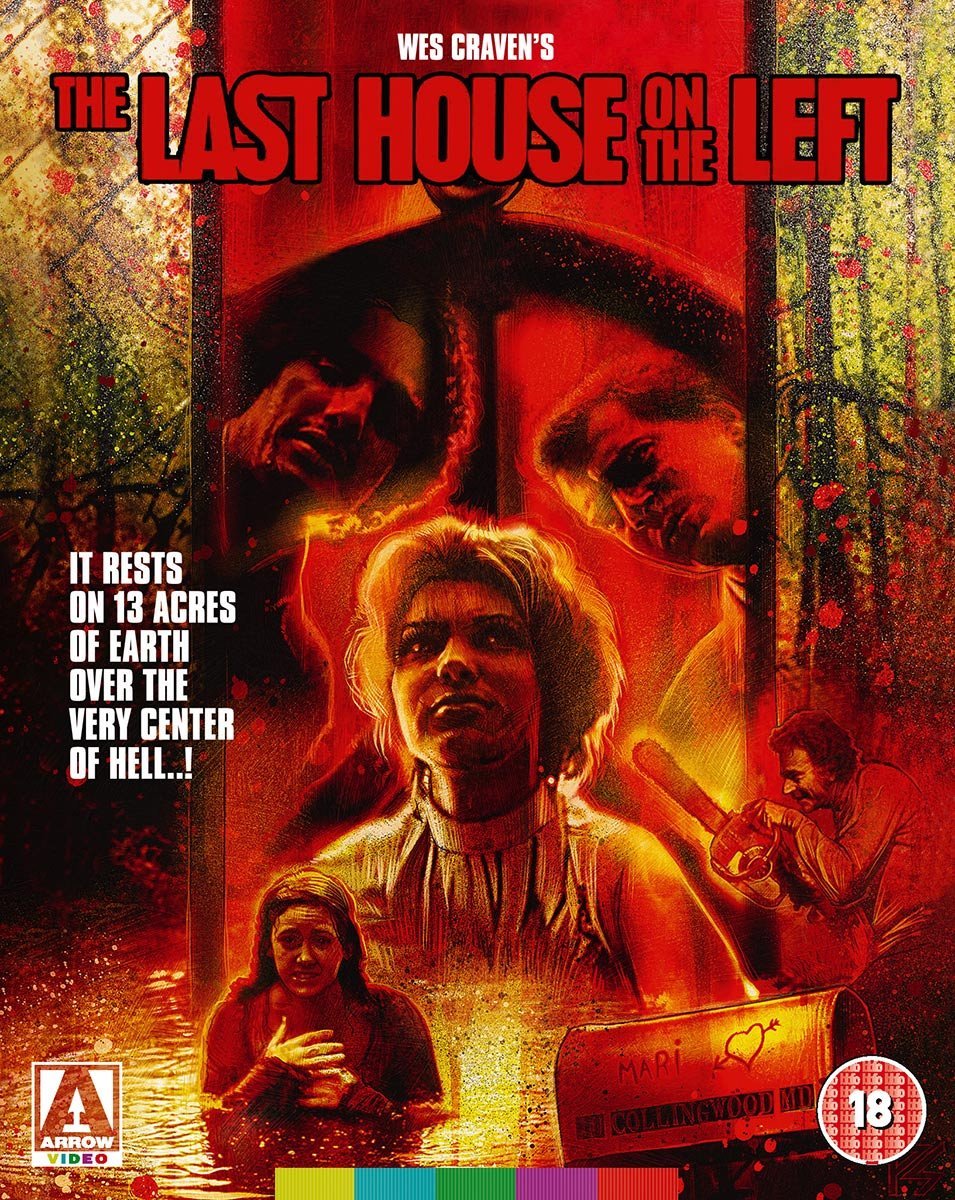

Last House on the Left (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd June 2018). |

|

The Film

Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972) Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972)

On her seventeenth birthday, Mari Collingwood (Sandra Peabody) plans to spend the evening with her more streetwise friend Phyllis Stone (Lucy Grantham) watching a band called Bloodlust, much to the chagrin of Mari’s decidedly bourgeois parents, dentist John Collingwood (Richard Towers) and his wife Estelle (Cynthia Carr). Meanwhile, convicted killers Krug Stillo (David Hess) and Fred ‘Weasel’ Podowski (Fred Lincoln) have escaped from prison, with the assistance of Sadie (Jeramie Rain) and Krug’s son Junior (Marc Sheffler), who Krug has hooked on heroin in order to make him more obedient. When Phyllis and Mari hit the streets before the concert, with the aim of buying some marijuana, they run into Junior, who lures them back to the hideout of Krug, Weasel and Sadie. There, the young women are trapped. The more savvy Phyllis attempts to reason with the hoodlums, but she is sexually assaulted in front of Mari. As the evening passes, John and Estelle notice the absence of Mari and contact the local police, but the sheriff (Marshall Anker) and his deputy (Martin Kove) are woefully inept, the sheriff insisting that Mari will return by her own volition. In the morning, the hoods stash Phyllis and Mari in the trunk of their car. They drive to the woods where their car breaks down and, ironically, they stop close to Mari’s parents’ house. They take the two young women into the woods and subject them to various acts of torture and sexual humiliation. When Krug returns to the car in order to retrieve a machete from the trunk (with the intention of using it on the girls), Phyllis runs interference with Weasel and Sadie, leaving Mari alone with Junior. Mari attempts to reason with Junior, who reveals himself to be a pitiable creature, manipulated into a life of crime and cruelty by his father but with a profound sense of humanity within him. With the hope of escaping, Mari gives to Junior the necklace (bearing the CND symbol) given to her as a birthday present by her parents.  Krug returns, and Phyllis is cornered in a cemetery where she is brutally murdered by Weasel and Sadie. Afterwards, Krug turns his attention towards Mari, using Weasel’s flickknife to carve his name into Mari’s chest before raping her. Subsequent to the rape, Mari wanders into the nearby lake, where Krug shoots her with a snub-nosed revolver. Krug returns, and Phyllis is cornered in a cemetery where she is brutally murdered by Weasel and Sadie. Afterwards, Krug turns his attention towards Mari, using Weasel’s flickknife to carve his name into Mari’s chest before raping her. Subsequent to the rape, Mari wanders into the nearby lake, where Krug shoots her with a snub-nosed revolver.

Seeking assistance with their vehicle, Krug and his gang change their clothes and, masquerading as traveling salespeople, approach the Collingwood home. John and Estelle are initially taken in by their disguises and offer them a place to sleep for the night. However, the Collingwoods notice the gang’s lack of manners at the dinner table, and Estelle recognises Mari’s necklace, which Junior is wearing. She overhears a conversation between the hoodlums which points to the location of her daughter’s body, by the lake. John and Estelle wander out there, finding Mari’s corpse. They return home and plot their revenge, booby-trapping their home and employing a level of savagery to match, or perhaps even surpass, that exhibited by Krug’s gang. An academic who walked away from a career in education to make ‘disreputable’ films – beginning with hardcore pornographic films and progressing, through Last House on the Left, on to the horror genre where he would make his most profound mark – Wes Craven was, despite the violence in his films, a sensitive filmmaker whose best work combines a combative sensibility with some often quite profound themes. Based on Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960, itself an adaptation of a Norwegian folk tale), but noticeably absent of that film’s focus on God and the miracle that takes place at the site of Karin’s murder (the appearance of the titular ‘virgin spring’), Last House on the Left employs Bergman’s picture’s symbolic use of bodies of water as liminal spaces where life is taken. Interestingly, in the manner of examples of classic pornographic literature such as John Cleland’s Fanny Hill, Last House on the Left masquerades as a narrative which is based on fact with its opening title, which declares ‘The events you are about to witness are true. Names and locations have been changed to protect those individuals still living’. As with Tobe Hooper’s later The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), this suggestion that the story is based on a ‘true’ account is compounded by the use of verite-style 16mm photography that adds a sense of realism to the events depicted in the film’s narrative.  A benchmark of what would become the rape-revenge subgenre during the 1970s, Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left was one of a triptych of films, along with Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972) and Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1973), whose themes would be exploited by numerous exploitation pictures that followed. Subsequent movies often aped these in one way or another, with either a Straw Dogs-like rural focus (William Fruet’s Death Weekend, 1976; Roberto Bianchi Montero’s Una donna per 7 bastardi, 1974) or a Death Wish-style emphasis on urban vigilantism (Abel Ferrara’s Ms 45, 1981; John Flynn’s Defiance, 1980). A benchmark of what would become the rape-revenge subgenre during the 1970s, Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left was one of a triptych of films, along with Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972) and Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1973), whose themes would be exploited by numerous exploitation pictures that followed. Subsequent movies often aped these in one way or another, with either a Straw Dogs-like rural focus (William Fruet’s Death Weekend, 1976; Roberto Bianchi Montero’s Una donna per 7 bastardi, 1974) or a Death Wish-style emphasis on urban vigilantism (Abel Ferrara’s Ms 45, 1981; John Flynn’s Defiance, 1980).

Craven’s picture was emulated throughout the 1970s, in terms of its narrative, title and marketing campaign (with its infamous, minimalistic poster declaring ‘To avoid fainting, keep repeating… it’s only a movie’). Its most obvious imitators include L’ultimo treno della notte (Late Night Trains/Night Train Murders, Aldo Lado, 1975), released in the US as both Last House – Part II and New House on the Left, which features two young women (Irene Miracle and Laura D’Angelo) who are murdered aboard a train, and whose killers inadvertently find themselves at the domicile of one of their victims’ families. Lado’s film also features a similarly counterpunctive use of music to Last House on the Left, making memorable use of a Demis Roussos song (‘A Flower’s All You Need’) over its opening credits. Some of Craven’s film’s other imitators are Casa sperduta nella parco (House on the Edge of the Park, Ruggero Deodato, 1979), which features David Hess in a Krug-like role as a proletarian rapist who intrudes upon a group of bourgeois goodtimers, accompanied on the soundtrack by Riz Ortolani’s choir-based song ‘Sweetly’; Avera vent’anni (To Be Twenty, Fernando di Leo, 1978), which shares Last House’s brutal shifts in tone, in which two good-natured young women meet an unpleasant end that symbolises the death of youthful innocence and naivete; and La settima donna (Last House on the Beach, Franco Prosperi, 1978), in which a group of teenage girls are terrorised by three hoodlums, until the nun (Florinda Bolkan) responsible for the teenagers decides to take revenge. Tony Williams also links Last House on the Left with a number of other pictures of the 1970s that featured ‘typical American families encounter[ing] their monstrous counterparts, undergo[ing] (or perpetuat[ing]) brutal violence, and eventually surviv[ing] with full knowledge of their kinship to their monstrous counterparts’ (Williams, 2014: np). Other examples of this trope include The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), in which a group of young people encounter a family of cannibals and graverobbers, and Wes Craven’s later The Hills Have Eyes (1977). As Williams suggests, these ‘bad’ families in 1970s horror and exploitation films have precedents in Westerns, such as the Hammonds in Sam Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country (1962) and the Tobin family in Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958). Last House on the Left explores this theme through the contrast between the Collingwood family and Krug’s makeshift ‘family’ of violent criminals, this juxtaposition coming to a head in the film’s later sequences, when Krug and his associates dress in imitation of respectable citizens in order to be given sanctuary in the home of John and Estelle Collingwood. Of course, despite their outward appearance, their behaviour soon betrays them: whilst they dine at the Collingwoods’ dinner table, Craven cuts from shots of John and Estelle to closeups of their guests as they show their lack of training in bourgeois etiquette by failing to use the cutlery correctly and guzzling the wine provided by their hosts. Tony Williams suggests that these films, in which the family encounters its opposite, offer a ‘disrupt[ion to] the ideological norms of family sitcoms such as Father Knows Best, I Love Lucy, Ozzie and Harriet’ (ibid.).  As a reimagining of The Virgin Spring, Williams argues, Last House on the Left depicts ‘[v]iolent outside forces attack[ing] a seemingly pure family’, the outcome of this conflict (the ‘good’ family’s use of violence in revenge against the ‘bad’ family) ‘emphasi[sing] that its dark family group actually represent violent forces within the average family’ (Williams, op cit.). At the outset of the film, Krug’s gang and the Collingwood family are ostensibly ‘opposites’, the film establishing a dialectical relationship between them through Craven’s use of crosscutting and parallel editing to connect the actions of Krug and company with the pairings of Mari and Phyllis, John and Estelle, and the sheriff and his deputy. The relationship between these two ‘families’ is, however, more complex than this: the film’s opening sequence, in which John Collingwood points out his daughter’s lack of a bra, declaring this to be ‘immodest’ and asserting that he can almost see her nipples, results in Mari subtly mocking her parents (telling Estelle that her generation wore bras which made their ‘tits stick out like torpedoes’). John is affronted by Mari’s choice of words, asking, ‘What is this “tits” business? Sounds like I’m back in the barracks’. John and Estelle then question Mari’s choice of friends, though Mari insists she’s safer going to the concert with Phyllis because, being from the wrong side of the proverbial tracks, Phyllis is more streetwise and capable of taking care of them both. Whilst Mari isn’t ‘out of control’, her quietly tense relationship with her parents – with its subtle suggestions of sexual repression – is contrasted with Krug’s relationship with Junior, who Krug has kept under his thumb by hooking Junior on heroin from a young age. By the end of the picture, John and Estelle have employed, in the service of their revenge, violence of an equally sadistic level as Krug and his gang: Estelle bites off the penis of Weasel and slits the throat of Sadie, leaving her to drown in her own blood as she falls into the family pool, whilst John beheads Krug with his chainsaw. Williams suggests that this theme, in which the opposition between the ‘good’ family and their ‘bad’ opposite is gradually broken down, ‘reflected a country facing involvement in a war involving military atrocities against innocent people. For Wes Craven, both Stillos and Collingwoods are “us”’ (ibid.). As a reimagining of The Virgin Spring, Williams argues, Last House on the Left depicts ‘[v]iolent outside forces attack[ing] a seemingly pure family’, the outcome of this conflict (the ‘good’ family’s use of violence in revenge against the ‘bad’ family) ‘emphasi[sing] that its dark family group actually represent violent forces within the average family’ (Williams, op cit.). At the outset of the film, Krug’s gang and the Collingwood family are ostensibly ‘opposites’, the film establishing a dialectical relationship between them through Craven’s use of crosscutting and parallel editing to connect the actions of Krug and company with the pairings of Mari and Phyllis, John and Estelle, and the sheriff and his deputy. The relationship between these two ‘families’ is, however, more complex than this: the film’s opening sequence, in which John Collingwood points out his daughter’s lack of a bra, declaring this to be ‘immodest’ and asserting that he can almost see her nipples, results in Mari subtly mocking her parents (telling Estelle that her generation wore bras which made their ‘tits stick out like torpedoes’). John is affronted by Mari’s choice of words, asking, ‘What is this “tits” business? Sounds like I’m back in the barracks’. John and Estelle then question Mari’s choice of friends, though Mari insists she’s safer going to the concert with Phyllis because, being from the wrong side of the proverbial tracks, Phyllis is more streetwise and capable of taking care of them both. Whilst Mari isn’t ‘out of control’, her quietly tense relationship with her parents – with its subtle suggestions of sexual repression – is contrasted with Krug’s relationship with Junior, who Krug has kept under his thumb by hooking Junior on heroin from a young age. By the end of the picture, John and Estelle have employed, in the service of their revenge, violence of an equally sadistic level as Krug and his gang: Estelle bites off the penis of Weasel and slits the throat of Sadie, leaving her to drown in her own blood as she falls into the family pool, whilst John beheads Krug with his chainsaw. Williams suggests that this theme, in which the opposition between the ‘good’ family and their ‘bad’ opposite is gradually broken down, ‘reflected a country facing involvement in a war involving military atrocities against innocent people. For Wes Craven, both Stillos and Collingwoods are “us”’ (ibid.).

In Adam Simon’s documentary The American Nightmare (2000), Craven pointed to Nick Ut’s Pulitzer Prize winning photograph of the aftermath of a napalm attack on the South Vietnamese village of Trang Bang as his ‘coming of age into realizing that Americans weren’t always the good guys and that things we could do could be horrendous or evil or dark or impossible to explain: My Lai, for instance’. During the scene in which Krug executes Mari by gunshot at the lake, Craven claimed to have directly quoted the ‘methodical execution style’ seen in the footage, and Eddie Adams’ famous photograph, of the execution of a Vietcong prisoner by South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan. Aside from the war in Vietnam, Last House on the Left also references the activities of Charles Manson’s ‘family’, in the name given to the character of Sadie (which alludes to Susan Atkins’ nickname ‘Sexy Sadie’), the Manson-like hold that Krug has over his associates (and especially his son Junior), and the frenzy with which the gang commit their murders. In the character of Sadie, the film also references the Women’s Lib movement, but when Sadie cites ‘equal representation’, she is suggesting that Krug and Weasel need to get a couple more women: ‘I ain’t putting out no more till we get a couple more chicks’, she says.  Against this tide of violence, the figures of authority are impotent. The sheriff and his deputy pass Krug and his gang’s car on their way to the Collingwood house it investigate Mari’s disappearance. The deputy asks the sheriff if they should take a look at the abandoned vehicle, but the sheriff tells him they have ‘more important things to do’. They enter the Collingwood home and speak with John and Estelle, as Mari and Phyllis are being terrorised in the woods nearby. The sheriff and deputy return to their office, but a radio broadcast describing the car used by Krug and his gang in their escape from prison provokes the sheriff into the realisation that he should have investigated the vehicle they saw by the roadside. They decide to return to the location, but their police vehicle has broken down, so they resort to hitch-hiking. The first car that stops is filled with youths who, when the sheriff and his deputy approach the vehicle, drive away and yell ‘We hate cops!’ However, the sheriff and his deputy are finally given a lift by a woman named Ada, who is driving a truck loaded with caged chickens. The sheriff and his deputy are, embarrassingly, forced to sit on top of the cab. Against this tide of violence, the figures of authority are impotent. The sheriff and his deputy pass Krug and his gang’s car on their way to the Collingwood house it investigate Mari’s disappearance. The deputy asks the sheriff if they should take a look at the abandoned vehicle, but the sheriff tells him they have ‘more important things to do’. They enter the Collingwood home and speak with John and Estelle, as Mari and Phyllis are being terrorised in the woods nearby. The sheriff and deputy return to their office, but a radio broadcast describing the car used by Krug and his gang in their escape from prison provokes the sheriff into the realisation that he should have investigated the vehicle they saw by the roadside. They decide to return to the location, but their police vehicle has broken down, so they resort to hitch-hiking. The first car that stops is filled with youths who, when the sheriff and his deputy approach the vehicle, drive away and yell ‘We hate cops!’ However, the sheriff and his deputy are finally given a lift by a woman named Ada, who is driving a truck loaded with caged chickens. The sheriff and his deputy are, embarrassingly, forced to sit on top of the cab.

Aside from its significance within the rape-revenge cycle of the 1970s, Last House on the Left is a key example of independent ‘regional’ genre cinema, one of a number of films from the 1960s and 1970s whose independence from the Hollywood machine during the post-Production Code era allowed its filmmakers to push the envelope in terms of what was allowed to be depicted onscreen. In fact, independent/regional genre films thrived on upping the ante in this regard, their willingness to show what would, or could not, be shown in Hollywood films both enabling the films to find an audience and differentiating them from their Hollywood brethren. H G Lewis’ Blood Feast (1963), which predates the abandonment of the Production Code, is a key film in this regard, as is George A Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968).  Of course, there is always space within any film for an aberrant or oppositional reading, but the violence in Last House on the Left exceeds any sense of it being presented for enjoyment or excitement. Tony Williams notes that ‘Last House condemns any audience member who complies with excessive violent displays’, suggesting that the picture ‘is an extremely complex film that unveils an ugly sadistic lust most horror films pander to’ (Williams, op cit.). Though the film’s most outrageous examples of violence occur in Krug and his gang’s murders of Phyllis and Mari, and the revenge enacted by the Collingwoods, the film’s opening sequences suggest a society riddled with – or at least obsessed with – violence. John is introduced reading a newspaper; Estelle asks him ‘What’s new in the outside world?’ ‘Same old stuff’, he responds, ‘Murder and mayhem’. The band Mari and Phyllis are planning to see, Bloodlust, are associated with lurid onstage acts: ‘Aren’t they the guys that dismember live chickens as part of their act?’, John asks Mari as she prepares to go out. When Mari sarcastically asserts that her ‘heart bleeds’ for those ‘poor chickens’, John asserts, ‘All that blood and violence. I thought you were supposed to be the peace and love generation’. Reputedly influenced by the graphic nature of news footage of the Vietnam War, Craven allows the film’s moments of violence to reach a level of excess, such as when Krug and his gang kill Phyllis, Weasel and Sadie launching into the young woman with a multitude of blows from Weasel’s flickknife. The moments of contact between the blade and Phyllis’ body are not presented via close-ups of the knife entering her but, in a manner comparable perhaps with the pivotal shower scene from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) in which viewers at the time reputedly believed themselves to have seen the blade entering the body of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), the violence of Phyllis’ death is played elliptically on the face of Phyllis herself as she slumps against Krug. Just as the moment seems to have come to an end, however, Craven ups the ante and leaves the viewer with a sense of unease by presenting a brief closeup of Sadie’s hands pulling Phyllis’ intestines out of her body. Craven’s initial cut of the film reputedly contained more of this material, but Craven trimmed it, believing that the violence was going too far. His decision was probably the correct one, this graphic shot being present onscreen for just the right amount of time before Craven carries us into another scene, allowing the brutality of what we have just witnessed to linger in the mind of the viewer. Following the murders of Phyllis and Mari, Krug and the others stand around, picking grass from their bloodstained hands, their faces showing an ambivalence – perhaps even a sense of regret – towards their violent actions, like the townsfolk who eagerly crowd around the hanging of the witch in the opening sequence of Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (Michael Reeves, 1968) only to disperse silently, a sense of shame hanging in the air, following her death. In this film, Craven seems to have a similar relationship with violence to Sam Peckinpah, who once commented in relation to the violence in The Wild Bunch (1969) that he wanted to ‘get people involved in [the violence] so that they are starting to go into the Hollywood television predictable reaction syndrome, and then twist it so that it’s not fun anymore, just a wave of sickness in the gut... It’s ugly, brutalizing and bloody fucking awful [....] And yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement because we’re all violent people’ (Peckinpah, quoted in Weddle, 1994: 334). Of course, there is always space within any film for an aberrant or oppositional reading, but the violence in Last House on the Left exceeds any sense of it being presented for enjoyment or excitement. Tony Williams notes that ‘Last House condemns any audience member who complies with excessive violent displays’, suggesting that the picture ‘is an extremely complex film that unveils an ugly sadistic lust most horror films pander to’ (Williams, op cit.). Though the film’s most outrageous examples of violence occur in Krug and his gang’s murders of Phyllis and Mari, and the revenge enacted by the Collingwoods, the film’s opening sequences suggest a society riddled with – or at least obsessed with – violence. John is introduced reading a newspaper; Estelle asks him ‘What’s new in the outside world?’ ‘Same old stuff’, he responds, ‘Murder and mayhem’. The band Mari and Phyllis are planning to see, Bloodlust, are associated with lurid onstage acts: ‘Aren’t they the guys that dismember live chickens as part of their act?’, John asks Mari as she prepares to go out. When Mari sarcastically asserts that her ‘heart bleeds’ for those ‘poor chickens’, John asserts, ‘All that blood and violence. I thought you were supposed to be the peace and love generation’. Reputedly influenced by the graphic nature of news footage of the Vietnam War, Craven allows the film’s moments of violence to reach a level of excess, such as when Krug and his gang kill Phyllis, Weasel and Sadie launching into the young woman with a multitude of blows from Weasel’s flickknife. The moments of contact between the blade and Phyllis’ body are not presented via close-ups of the knife entering her but, in a manner comparable perhaps with the pivotal shower scene from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) in which viewers at the time reputedly believed themselves to have seen the blade entering the body of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), the violence of Phyllis’ death is played elliptically on the face of Phyllis herself as she slumps against Krug. Just as the moment seems to have come to an end, however, Craven ups the ante and leaves the viewer with a sense of unease by presenting a brief closeup of Sadie’s hands pulling Phyllis’ intestines out of her body. Craven’s initial cut of the film reputedly contained more of this material, but Craven trimmed it, believing that the violence was going too far. His decision was probably the correct one, this graphic shot being present onscreen for just the right amount of time before Craven carries us into another scene, allowing the brutality of what we have just witnessed to linger in the mind of the viewer. Following the murders of Phyllis and Mari, Krug and the others stand around, picking grass from their bloodstained hands, their faces showing an ambivalence – perhaps even a sense of regret – towards their violent actions, like the townsfolk who eagerly crowd around the hanging of the witch in the opening sequence of Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (Michael Reeves, 1968) only to disperse silently, a sense of shame hanging in the air, following her death. In this film, Craven seems to have a similar relationship with violence to Sam Peckinpah, who once commented in relation to the violence in The Wild Bunch (1969) that he wanted to ‘get people involved in [the violence] so that they are starting to go into the Hollywood television predictable reaction syndrome, and then twist it so that it’s not fun anymore, just a wave of sickness in the gut... It’s ugly, brutalizing and bloody fucking awful [....] And yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement because we’re all violent people’ (Peckinpah, quoted in Weddle, 1994: 334).

Video

The 1080p presentation of the main feature, on disc one, takes up 26.6Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Shot on 16mm for a pittance, Last House on the Left has a very coarse aesthetic, with a style that steers close to the conventions of cinema verite: compositions are often loose and awkward, the camera often handheld. As if to reinforce the influence of New Wave cinemas on the film, Craven (who also edited the picture) employs jump cuts and symbolic montage throughout the film; through the editing, he allows individual scenes to overlap via the use of crosscutting/parallel editing, rather than treating them as separate entities. The 1080p presentation of the main feature, on disc one, takes up 26.6Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Shot on 16mm for a pittance, Last House on the Left has a very coarse aesthetic, with a style that steers close to the conventions of cinema verite: compositions are often loose and awkward, the camera often handheld. As if to reinforce the influence of New Wave cinemas on the film, Craven (who also edited the picture) employs jump cuts and symbolic montage throughout the film; through the editing, he allows individual scenes to overlap via the use of crosscutting/parallel editing, rather than treating them as separate entities.

Arrow’s presentation features a new 2k restoration based on original film elements. These elements are the same as those used for MGM’s Blu-ray release in the US, though there are some noticeable differences between that disc and Arrow’s new restoration. (See the full-size screengrabs linked to at the bottom of this review for illustration of the following points.) In comparison with MGM’s Blu-ray presentation, Arrow’s presentation opens up the framing slightly on all four sides of the frame. The MGM features whites that are closer to empirical white (see the white of Fred Lincoln’s shirt in the large frame grabs below: Comparison 7), though the difference is incredibly subtle. Elsewhere, the autumnal colour of the leaves seems slightly more rich on the MGM disc, whereas on the Arrow release these leaves seem much more green and less autumnal (see Comparison 5). The MGM disc features some noticeable sharpening and tonal curves that are too sharp: on that disc, some of the highlights veer towards being blown. (For example, see the specular highlights on Jeramie Rain’s face in the shot, again included at the bottom of this review, in which the gang are surrounding the gagged Lucy Grantham: Comparison 2.) On the other hand, Arrow’s presentation features some noticeably muted grain. (For illustration of this, look at Sandra Peabody’s face in the shot in which David Hess stands over her with the machete in his hand: Comparison 4.)  In terms of damage, some shots display instability in the emulsions; and throughout a good portion of the film, there is a visible smudge or smear either on the lens used to shoot the picture or on the device used to capture the film digitally. This is more noticeable in some scenes than others, but obviously, those shots in which this portion of the frame contains a consistent colour or surface will enable its presence to be more obvious. This appears in the lower half of the image, about a third of the way across the horizontal plane (from left to right). (See the full-size screengrabs at the bottom of this review of the shot in which the sheriff and his deputy attempt to flag down Ada’s chicken truck: Comparison 6.) This is present in both Arrow’s and MGM’s HD presentations. The MGM presentation also features a number of shots, at various points throughout the film, in which a bold vertical line can be seen at the extreme left hand edge of the frame. (This is most likely a result of the manner in which the negative for those specific shots was handled during shooting or developing.) For Arrow’s presentation, this vertical line has not been removed entirely but is much more subdued. (As an example, look at the shot of John and Estelle Collingwood drinking from tumblers: Comparison 8.) In the scene in which Estelle speaks with Weasel, before taking him outside, a hair(?) enters the gate on frame right and shoots into the middle of the image, gradually working its way to the bottom of the frame (Comparison 7). Again, this is present in both HD presentations and has been present in every digital and pre-digital presentation that I can remember seeing. In terms of damage, some shots display instability in the emulsions; and throughout a good portion of the film, there is a visible smudge or smear either on the lens used to shoot the picture or on the device used to capture the film digitally. This is more noticeable in some scenes than others, but obviously, those shots in which this portion of the frame contains a consistent colour or surface will enable its presence to be more obvious. This appears in the lower half of the image, about a third of the way across the horizontal plane (from left to right). (See the full-size screengrabs at the bottom of this review of the shot in which the sheriff and his deputy attempt to flag down Ada’s chicken truck: Comparison 6.) This is present in both Arrow’s and MGM’s HD presentations. The MGM presentation also features a number of shots, at various points throughout the film, in which a bold vertical line can be seen at the extreme left hand edge of the frame. (This is most likely a result of the manner in which the negative for those specific shots was handled during shooting or developing.) For Arrow’s presentation, this vertical line has not been removed entirely but is much more subdued. (As an example, look at the shot of John and Estelle Collingwood drinking from tumblers: Comparison 8.) In the scene in which Estelle speaks with Weasel, before taking him outside, a hair(?) enters the gate on frame right and shoots into the middle of the image, gradually working its way to the bottom of the frame (Comparison 7). Again, this is present in both HD presentations and has been present in every digital and pre-digital presentation that I can remember seeing.

Accounting for the limited technical resources available to the filmmakers when making the picture, this presentation displays a good level of detail, though the lenses used during production weren’t tack sharp and the plane of focus is sometimes a little ‘off’ – presumably owing to either the characteristics of the lens/es or careless/inaccurate focus pulling during the shoot. Nevertheless, this presentation seems consistent with what one would expect from a film shot on 16mm under such circumstances, with good contrast levels: defined midtones bleeding into deep blacks. The day for night sequence in which John and Estelle discover Mari’s body looks terribly funky but always has. Again, this is a limitation of the shoot, and Arrow’s Blu-ray is true to source in capturing it.  Last House on the Left was rejected by the BBFC when submitted for a cinema certificate in 1974, under the title ‘Krug and Company’ and in a version that featured some slightly different footage to the edit of the film that is more familiar to viewers. (This alternate cut is included on this Blu-ray release, and has been released on DVD in the UK before.) Although it received an uncut VHS pre-cert release on the Replay label in 1982, following the Video Recordings Act Last House on the Left was absent on home video in the UK (though not technically ‘banned’, no distributor dared to submit it because it was open knowledge that the BBFC would without doubt reject it) until it was submitted to the BBFC for cinema certification in 1999. Somewhat remarkably, the BBFC suggested they would pass the film with about a minute and a half’s worth of cuts to scenes depicting the sexual humiliation and torture of Mari and Phyllis. However, the distributor failed to make these cuts. When the film was submitted for home video classification in 2001, the BBFC demanded 16s of cuts. The distributor made an appeal to the Video Appeals Committee, but this gambit backfired when the VAC suggested that further cuts (beyond the 16s of cuts imposed by the BBFC) would need to be made in order to make the film acceptable for home video distribution. These cuts were to the scene in which Krug makes Phyllis wet herself; the murder of Phyllis, including the shot in which Sadie pulls Phyllis’ intestines out of her torso; and the scene in which Krug carves his name in Mari’s chest. When the film was resubmitted in 2008 by Metrodome, the BBFC waived their previous cuts and allowed the film to be released on home video in its uncut form. This new Blu-ray release of the film contains the uncut version of the film, with a running time of 84:12 mins. Last House on the Left was rejected by the BBFC when submitted for a cinema certificate in 1974, under the title ‘Krug and Company’ and in a version that featured some slightly different footage to the edit of the film that is more familiar to viewers. (This alternate cut is included on this Blu-ray release, and has been released on DVD in the UK before.) Although it received an uncut VHS pre-cert release on the Replay label in 1982, following the Video Recordings Act Last House on the Left was absent on home video in the UK (though not technically ‘banned’, no distributor dared to submit it because it was open knowledge that the BBFC would without doubt reject it) until it was submitted to the BBFC for cinema certification in 1999. Somewhat remarkably, the BBFC suggested they would pass the film with about a minute and a half’s worth of cuts to scenes depicting the sexual humiliation and torture of Mari and Phyllis. However, the distributor failed to make these cuts. When the film was submitted for home video classification in 2001, the BBFC demanded 16s of cuts. The distributor made an appeal to the Video Appeals Committee, but this gambit backfired when the VAC suggested that further cuts (beyond the 16s of cuts imposed by the BBFC) would need to be made in order to make the film acceptable for home video distribution. These cuts were to the scene in which Krug makes Phyllis wet herself; the murder of Phyllis, including the shot in which Sadie pulls Phyllis’ intestines out of her torso; and the scene in which Krug carves his name in Mari’s chest. When the film was resubmitted in 2008 by Metrodome, the BBFC waived their previous cuts and allowed the film to be released on home video in its uncut form. This new Blu-ray release of the film contains the uncut version of the film, with a running time of 84:12 mins.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is bassy and deep; dialogue is audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included too. These are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the film’s dialogue.

Extras

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

Last House on the Left (84:12) - Audio commentary with Bill Ackerman and Amanda Reyes. This new audio commentary features podcaster Bill Ackerman and Amanda Reyes, author of a pretty good book on US TV movies made in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. The commentators are warm and engaging, but – and this is no slight against their contributions – the track feels largely redundant when set against the two archival commentary tracks also included on this disc. There’s much discussion of the commentators’ relationships with the film and some good second hand information presented, but a lot of it is descriptive of the participants’ careers or the narrative, and it would have been nice to have seen a little more critical engagement with the film’s themes and/or the filmmaking techniques employed by Craven and his crew. - Audio commentary with Wes Craven and Sean S Cunningham. This track has appeared on a number of the film’s previous DVD releases and features Craven and Cunningham on fine form. Their recollections of the film’s production are vivid, and their interactions are warm and witty. The always-articulate Craven offers some cogent reflections on his intentions with the film. It’s an excellent track. - Audio commentary with David Hess, Marc Sheffler and Fred Lincoln. Another excellent commentary track that has appeared on many of the film’s previous DVD releases, this one features Hess, Sheffler and Lincoln talking about the picture. The three actors discuss their relationships with the other actors – particularly Sandra Peabody and Lucy Grantham – and reflect on the role of the film within their respective careers. - Isolated Music and Effects Track. - Optional introduction by Wes Craven (0:40). Craven warns the viewer to ‘remove any small children or animals from the room’ and ‘take some sort of tranquiliser yourself if you’re unstable in your psychological makeup’.

- ‘Still Standing: The Legacy of The Last House on the Left’ (14:54). Recorded in 2009 for MGM’s previous home video release of the film, this interview with Wes Craven sees the director reflecting on the lasting impact of the picture. He claims he wrote the film without realising the import of the material, but realised the power of the material when the picture was in production. Craven also discusses the ways in which the film was impacted by its cultural context – in particular the ‘really shocking footage’ coming out of the war in Vietnam. - ‘Celluloid Crime of the Century’ (39:34). Made by Blue Underground in 2002 and previously included on the film’s DVD release from Anchor Bay, this documentary contains input from Craven, producer Sean S Cunningham and the cast (Hess, Rain, Lincoln, Sheffler and Kove). The participants talk about the origins of the project, and Craven discusses the manner in which he was impacted by the violence within the footage of the Vietnam War and how this jarred with the chaste depiction of violence in most films. The film’s connection with Bergman’s The Virgin Spring is examined, and the participants reflect on their roles in the production of the film, discussing Craven and Cunningham’s input as a director-producer team. - ‘Scoring Last House’ (9:44). Another featurette made for the 2002 Anchor Bay release of the film, ‘Scoring Last House’ is an interview with David Hess, who talks about his musical background. He discusses his approach to writing the score for the picture and performs some of the songs. - ‘It’s Only a Movie: The Making of Last House on the Left’ (29:01). Also made in 2002, this piece features Craven, Cunningham, Lincoln, Lucy Grantham, Hess, Kove, assistant editor Steve Miner and Sheffler talking about the development and production of the film. There’s much overlap with the (arguably better) ‘Celluloid Crime of the Century’, but this piece is nevertheless interesting, especially for the inclusion of interview footage with Grantham (who is absent from ‘Celluloid Crime of the Century’).

- ‘Forbidden Footage’ (8:12). In another archival feature, Craven, Cunningham, Lucy Grantham and Steve Miner talk about the censorship of the film and the more extreme material they shot, Craven offering an interesting philosophical justification for the scene in which Sadie disembowels Phyllis. - ‘Junior’s Story’ (14:24). A recent interview with Marc Sheffler, from 2017, sees the actor discussing how he came to be cast in the film. He talks at length about his relationships with the other cast members, especially David Hess. He says that the film ‘wasn’t the most professional of productions’ and ‘Wes kept it rough’ in order to ‘lift a window and give the audience a peak at a horrific crime in process’. For Sheffler, the coarse nature of the film is essential to its impact. - ‘Blood and Guts: A Conversation with Anne Paul’ (13:52). In a new interview recorded this year, Paul, one of the makeup artists on the film, reflects on the production: Paul auditioned for the roles of Mari and Phyllis, and when she was turned down she volunteered herself for the role of makeup artist on the film. Though she bluffed her way into this role without any prior experience, she reasoned that she ‘had a background in cosmetology and a background in magic’ which she could combine and found that film makeup effects came naturally to her. - ‘The Road Leads to Nowhere: The Locations of Last House’ (5:48). In this interesting albeit too brief new featurette, former editor-in-chief of Fangoria Michael Gingold visits some of the film’s locations.

- Deleted Scene: ‘Mari Dying at the Lake’ (1:04). This scene, which depicts John and Estelle discussing a barely alive Mari by the lake, is included in the alternate cut of the film entitled Krug & Company but is presented here in isolation. (In the finished cut of the film, it’s clear that Mari is moving when her parents find her, so the suggestion in the post-dubbed dialogue that she is already dead always seemed a little jarring; this version of the scene arguably works much better in situ.) - Outtakes and Dailies (47:38). This incredible archive of outtakes surpasses what has been released on previous home video releases and is a highlight of Arrow’s new special edition. The material is provided courtesy of Roy Frumkes. The footage is all silent but offers a fascinating insight into the production and editing of the film. (The clapperboard, interestingly, carries the film’s originally intended title, ‘Night of Vengeance’.) The outtakes focus on the death of Phyllis; some material featuring John and Estelle at home; the murder of Mari (including the raw footage of her disembowelment at the hands of Sadie); footage of the gang searching for Phyllis in the woods; additional material from the opening scene in which Mari prepares to go out with Phyllis; some much more explicit footage of the scene in which the gang force Phyllis and Mari to ‘make it with each other’ (in the words of Junior), including full nudity from both Sandra Peabody and Lucy Grantham, with Sadie performing cunnilingus on Mari; additional material from the scene in which Mari tries to reason with Junior. - Trailers, TV and Radio Spots: Trailer 1 (1:14); Trailer 2 (2:06); TV Spot (0:32); Radio Spots (5:45). - Image Galleries: Stills (1:05); Promotional Material (1:05).  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

This disc includes two alternate cuts of the film: - Krug & Company (83:50). This cut of the film features some alternate takes and slightly different editing decisions. The most significant difference is the inclusion of the alternate version of the scene in which John and Estelle discover Mari’s body; in this edit of the film, Mari is still alive and shares some dialogue with her parents. (Technical specs are the same as for the main presentation of the film on disc 1 – a LPCM 1.0 track, optional English HoH subs and the 1.85:1 aspect ratio.) - The R-rated cut (81:52). This is the cut of the film that received an ‘R’ rating in the US, which reduces the film’s violent content quite considerably. - ‘The Craven Touch’ (17:10). In a new featurette, various people who collaborated with Craven – including Sean S Cunningham, Peter Locke, Charles Bernstein, Mark Irwin and Amanda Wyss – pay tribute to Craven, discussing his skill and technique as a film director. - ‘Early Days and “Night of Vengeance”’ (9:04). In a new interview, Roy Frumkes talks about Last House on the Left, suggesting that ‘when one sees Last House on the Left today, it’s coloured by all the similar films that have come after it’ and it’s difficult to recognise how disturbing the film was at the time of its original release. Frumkes reflects on his friendship with Craven, and Craven’s assertion that working in Hollywood was ‘like a form of martial arts’. - ‘Tales That’ll Tear Your Heart Out’ (11:19). This is the footage that Wes Craven shot for inclusion in Frumkes’ never-completed anthology film Tales That’ll Tear Your Heart Out. It is silent and brief but is an excellent inclusion in this set.

- Marc Sheffler Q&A (12:25). Sheffler is shown fielding questions from the audience at a screening of Last House in LA in 2017. - ‘Songs in the Key of Krug’ (9:41). This is billed as ‘never before seen footage’ of Hess culled from outtakes, presumably from Blue Underground’s 2002 interview with him. Hess talks about his admiration of John Garfield and his approach to acting. He also reflects on how the film uses his music as a counterpoint to the onscreen action. Hess was always an incredible interviewee, and these snippets are fascinating. - ‘Krug Conquers England’ (24:12). This footage from the UK’s first official public screening of Last House in 2000, when it was screened alongside The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, sees Hess on stage with his guitar and off stage with the fans in attendance. Hess and others, including Gunnar Hansen, are interviewed about the film and the matter of film censorship.

Overall

Last House on the Left is a picture that divides opinion, and it’s difficult to make a summative statement about the film without offering one’s personal opinions and experiences with the film. Probably like many people of a similar age, I first encountered Last House on the Left via a copy of the pre-cert Replay VHS release. It seems strange to think that such a transgressive picture has had both a relatively glossy remake and a number of extras-laden digital home video releases. On my first experience with the film, watching it via the aforementioned Replay VHS release, I found the shifts in tone jarring and Hess’ sometimes-sweet music distracting. However, as the years have passed, I’ve come to the opinion that Craven’s counterpunctive use of music in this picture is an extraordinary coup, and the comic scenes involving the sheriff and his deputy have, aside from some wonderful little references to vaudeville and early screen comedy, a strong thematic importance in establishing just how misguided and impotent figures of authority are within this film. (It’s worth mentioning the manner in which, in his score for the film, Hess mixes major and minor keys with ease, creating a subtly unsettling soundscape, and includes some lyrics that are outwardly innocent but which, within the context of the film, have an ominous meaning – for example, the line ‘Gathering cherries off the ground’.) The film’s nihilism is captured in the lyrics of Hess’ title song (‘The Road Leads to Nowhere’) and the film’s stark contrast with the intimations of spirituality in its model, Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring. The film’s structure is folkloric, betraying its roots in The Virgin Spring (and the folk tale on which that film is based). Even the film’s most vehement detractors can’t deny the lasting impact the film has had; the value of this impact is, however, in the eye of the beholder. Last House on the Left is a picture that divides opinion, and it’s difficult to make a summative statement about the film without offering one’s personal opinions and experiences with the film. Probably like many people of a similar age, I first encountered Last House on the Left via a copy of the pre-cert Replay VHS release. It seems strange to think that such a transgressive picture has had both a relatively glossy remake and a number of extras-laden digital home video releases. On my first experience with the film, watching it via the aforementioned Replay VHS release, I found the shifts in tone jarring and Hess’ sometimes-sweet music distracting. However, as the years have passed, I’ve come to the opinion that Craven’s counterpunctive use of music in this picture is an extraordinary coup, and the comic scenes involving the sheriff and his deputy have, aside from some wonderful little references to vaudeville and early screen comedy, a strong thematic importance in establishing just how misguided and impotent figures of authority are within this film. (It’s worth mentioning the manner in which, in his score for the film, Hess mixes major and minor keys with ease, creating a subtly unsettling soundscape, and includes some lyrics that are outwardly innocent but which, within the context of the film, have an ominous meaning – for example, the line ‘Gathering cherries off the ground’.) The film’s nihilism is captured in the lyrics of Hess’ title song (‘The Road Leads to Nowhere’) and the film’s stark contrast with the intimations of spirituality in its model, Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring. The film’s structure is folkloric, betraying its roots in The Virgin Spring (and the folk tale on which that film is based). Even the film’s most vehement detractors can’t deny the lasting impact the film has had; the value of this impact is, however, in the eye of the beholder.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation is very good indeed. The presentation of the main feature is subtly different to the presentation of the film on MGM’s competing Blu-ray release from the US, but it’s in the breadth and depth of contextual material that Arrow’s release shines. The inclusion of the Krug & Company alternate cut is a significant coup, as are the new interviews, but the gallery of outtakes is a major draw of this release. It’s difficult to imagine a more comprehensive release of Craven’s film appearing on home video in the future, and this release of Last House on the Left comes with a very strong recommendation. Reference: WEDDLE, David, 1994: ‘If They Move... Kill ‘Em!’: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah. New York: Grove Press Williams, Tony, 2014: Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film. University Press of Mississippi Please Click to Enlarge: Comparison with MGM release: Comparison 1 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 2 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 3 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 4 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 5 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 6 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 7 Arrow:

MGM:

Comparison 8 Arrow:

MGM:

|

|||||

|